CHAPTER 13

PROJECT PLANNING

“Amid a multitude of projects, no plan is devised.”

PUBLILIUS SYRUS, CIRCA 42 B.C.

13.1 INTRODUCTION

The most important responsibility of the project team is to develop the project plan in consort with other supportive stakeholders. Project planning is reflective thinking about the project’s future in relationship to its present role in the design and execution of enterprise strategies. The project plan must be harmonious with the strategic plan of the enterprise, the functional plans, and, where appropriate, with the plans of the relevant stakeholders. If adequate project plans are developed, then an important standard for monitoring, evaluating, and controlling the application of project resources is available. If the project plans are inadequate, then the review of the project during its life cycle is greatly impaired.

In this chapter, a conceptual model of project planning is offered, along with a description of planning processes, considerations, and results that can be expected from adequate planning. The work breakdown structure is put forth as an absolute preliminary initiative to build on for the development of other project plans—such as schedules, scheduling techniques, planning charts, and networking techniques. A summary is given of the project planning elements, along with life-cycle planning, cost estimating, statement of work, project specification, and supporting functional plans. A citation of the generic work packages of project planning is offered as a template to guide the development of more specific planning work packages for individual projects. Included in the chapter content is a summary of the planning for project partners and outsourcing of project management, two growing areas of interest of project-driven organizations today.

13.2 THE IMPORTANCE OF PLANNING

Project planning is an important part of the “deciding” aspect of the project team’s job to think about the project’s future in relationship to its present in such a way that organizational resources can be allocated in a manner which best suits the project’s purposes. More explicitly, project planning is the process of thinking through and making explicit the objectives, goals, and strategies necessary to bring the project through its life cycle to a successful termination when the project’s product, service, or process takes its rightful place in the execution of project owner strategies. This chapter offers an overview of the project planning function placed in the context of enterprise planning.

In Chap. 2, strategic and organizational planning is covered. The context or planning within the organization is depicted in Fig. 2.2. This figure shows the hierarchical relationship for the enterprise, with projects subordinate to the organization’s mission, objectives, goals, and strategies. The operational plans and organizational design influence how project planning will be accomplished. For purposes of this chapter, project and program planning are considered the same.

Three types of plans are interrelated in an enterprise: the strategic plan, the functional plans, and the project plans. Project planning involves the development of a strategy for the commitment of resources to support the project objectives and goals. The project plan reflects the strategic plan of the enterprise in providing guidance in the likely forthcoming “strategic fit” of the “stream of projects” in the enterprise. The functional plans provide detailed guidance on how resources will be used to support the project purposes. All three plans are essential guides for the use of resources, as well as providing reciprocal guidance on how the three plans work together during their execution in creating value for the enterprise.

Project planning is a rational determination of how to initiate, sustain, and terminate a project. McNeil and Hartley define the basic concepts of project planning as developing the plan in the required level of detail with accompanying milestones, and the use of available tools for preparing and monitoring the plan.1

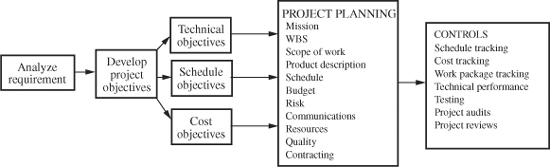

Project planning and controls are interrelated. Planning prescribes the path to be followed in executing the project, whereas the controls are the means to collect, analyze, compare, and correct. Project controls are an integral part of project planning. A useful flowchart model (Fig. 13.1) shows this interrelationship and shows the sequence in which planning is required.

FIGURE 13.1 A flowchart of typical planning and control functions.

Project planning addresses work to be accomplished during a project to meet the defined goals and objectives. It also identifies those activities and strategies that are detrimental to a project’s successful completion. The planning process entails a system of continual elaboration of details until there is visibility into the work.

The optimum project plan provides the appropriate level of detail to guide the performing team to successful completion of the work. Too much detail clouds the directions and makes the plan cumbersome. Too little detail leaves gaps in the instructions and opens the door for error in work processes.

13.3 PLANNING REALITIES

The planning ethos of the 1970s, rooted in the extrapolation of history, has been discredited by the “bends in the trends” exemplified by the oil crises and the political and social upheavals of the late 1980s and early 1990s. It is giving way to a new approach to strategic planning. This new approach is based on a visionary view of the future gained by a growing awareness of the possibility of long-term strategic alliance building, project partnering, sharing of risk in exploiting new technologies and processes leading to earlier commercialization, and continuous improvement of product, service, and process development and implementation in maintaining a competitive edge.

Planning is the most challenging activity for a leader or manager. Planning starts with the development of a vision—the ability to see something that is invisible to others. People in general find that it is more comfortable to do the work than to plan. All too often, people equate activity with progress. Taking time to think through a plan of action for the future is not always considered active management or leadership. Planning involves thinking through the possibilities and the probabilities of the future, and then developing a strategy for how the organizational resources will be positioned to take advantage of future competitive conditions.

Planning is a responsibility of the project leader. Finding ways to get the whole-hearted cooperation of team members and other stakeholders will facilitate the planning process and improve the chances of the development of a project plan to which members of the project team are committed.

Planning for the use of resources precedes the monitoring, evaluation, and control of resources. Insufficient front-end planning, unrealistic project plans, failing to estimate the degree of complexity, and lack of consideration for the project’s objectives will lead to reduced accomplishment of project objectives. When planning is done by an active, participating project team, the interactions and communications give greater insight to the project work. Interactions among the team members help develop the team and give the team members greater ease in dealing with each other. This guides the future use of organizational resources.

13.4 A CONCEPTUAL MODEL OF PLANNING

Project planning is preceded by comprehensive organizational strategic planning, because projects are integral elements of organizational strategies. A conceptual model, depicting the strategic context of organizational planning that includes both strategic planning and strategic implementation, appears in Fig. 13.2.2

FIGURE 13.2 Elements in the project-driven matrix management philosophy.

Strategic considerations are addressed in Chap. 2 and will not be restated here. This section will address the project and how planning is accomplished. It is well to remember that projects are building blocks of the enterprise and that all projects must contribute to the organization’s mission, as connected through organizational objectives and goals that are implemented through organizational strategies.

13.5 PROJECT PLANNING MODEL

Project planning begins within the framework of strategic planning in the organization. For example, the strategic planning phase at a steel corporation led to the approval of a comprehensive facility feasibility study for the location and configuration of the steel plant. As a result of this feasibility study, which evaluated seven alternative sites, the plant location was fixed at Cleveland, Ohio. During the planning for this facility, several options were considered, ranging from turnkey contract to construction management consultant to the owner acting as its own general contractor with sub-contractors and/or in-house personnel. These options were considered in detail before final project planning was carried out with approved cost estimates and milestone schedules.

The strategic context of organizational planning, depicted in Fig. 13.2, sets the stage for project planning. Projects must adhere to the strategic “umbrella” to assure flow down of the enterprise’s mission, vision, objectives, goals, and strategies. Using these concepts, project planning becomes an elaboration of the overall approach to business and provides for consistently building on the enterprise’s capability to perform work through projects.

Understanding the strategic approach to business and linking that to the project planning will provide the means to pursue work that supports the organization’s objectives and goals by using strategies that are adopted and used by the organization. Ensuring that projects, as building blocks for the business, contribute to the organization’s growth and improvement is critical to future well-being through the appropriate use of resources.

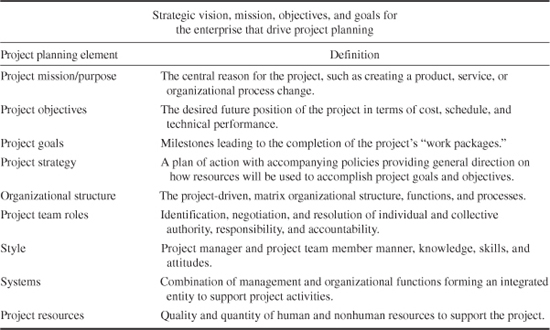

Table 13.1 depicts the hierarchical approach at the project level and establishes an overall framework for project planning. This is an extension of the concepts in Fig. 13.2, which provides the umbrella for project planning. The definitions provide an understanding for each key element.

TABLE 13.1 Project Planning in a Strategic Context

13.6 PROJECT PLANNING PROCESS

Projects often extend for many years into the future. Thus, a project plan for such projects becomes both operational (short term) and strategic (long term). It follows that the project planning process requires both operational and strategic thinking. Creativity, innovation, and the ability to “think prospectively” form the basis for the project planning process. The real value of such a process is a framework of things to consider for a project’s life cycle. A project planner’s philosophy encompasses characteristics such as:

• The need to search out objective data that provide the basis for project planning decision making

• The value of questioning assumptions, databases, and emerging project strategies to test their validity and relevance

• An ongoing obsession with where the project should go and how it is going to get there

• A demonstrated ability to view project opportunities in the largest possible context and to constantly seek an understanding of how everything fits together during the project’s life cycle

• A faith that, given ample opportunity, a bisociation will occur: the fitting together of separate events or forces on the project.3

Individuals making key project planning decisions today will have a long-term strategic impact on the organization. Generally, the strategic roles of key individuals involved in project planning are as follows:

• The board of directors reviews and approves (or redirects for further study) key project plans and maintains surveillance over the implementation of the plans.

• Senior management directs the design, development, and implementation of a strategic planning system and a project planning philosophy and process for the corporation.

• Functional managers are responsible for the integration of state-of-the-art functional technology into the project plans.

• The project manager is responsible for integrating and coordinating the project planning activity.

• The work package manager is responsible for providing input to the project plans.

• Professionals participate as required in contributing to the project planning processes.

By involving these individuals in the roles as described, key people are afforded the opportunity to participate in project planning. Of course, such participation requires relevant knowledge, skill, and insight into both the theory and the practice of project planning. By maximizing the participation of key individuals in project planning, the overall value of the project plan should be improved. One large project-driven organization recognized the value of project planning like this:

• During the early 1960s, after hundreds of projects had been completed, it became apparent that many projects successfully achieved their basic project objectives, whereas some failed to achieve budget, schedule, and performance objectives originally established.

• The history of many of these projects was carefully reviewed to identify conditions and events common to successful projects, vis-à-vis those conditions and events that occurred frequently on less successful projects. A common identifiable element on most successful projects was the quality and depth of early planning by the project management group. Execution of the plan, bolstered by strong project management control over identifiable phases of the project, was another major reason why the project was successful.4

Thus, project planning is the “business” of many individuals in the organization. Understanding planning concepts and how to develop realistic plans, adds value to the organization and its ability to reach into the future to lay out a path for success.

Project planning may be considered a form of information development and communications. As the project team develops the project plan, the project team should learn more about the project goals, strategies, and team member roles. The project objectives then can be decided in terms of cost, schedule, and technical performance. Satisfaction of project goals is accomplished through the completion of the project work packages. The project strategy is a plan of action with accompanying policies, procedures, and resource allocation schemes, providing general direction of how the organizational effort will be used to accomplish project goals and project objectives.

Simultaneous project planning is the process of having the project team consider all aspects, issues, and resources required for the project plan on a concurrent basis. Concurrent planning means that everything that can or might impact the project is reviewed during the planning phase to ensure that an explicit decision is made concerning the role that all resources, however modest, might have on the project. Project start-up workshops can be useful in the planning phase of a project to help identify and get people committed to the notion of thinking through all probable and possible aspects of the project to be reflected in the project plan.5

13.7 PROJECT PLANNING CONSIDERATIONS

Many projects are started before the requirements are fully defined and understood. The lack of requirements, which may be the specification for a product, can allow the planners to drift away from the customer’s needs. Once project planning starts in the wrong direction, it is difficult to correct. Like many other phenomena, the first 20 or 30 percent of the planning effort establishes a direction for the project.

The customer’s requirements define what the project should be. Planners who understand the customer’s requirements can collect the information to plan the project and apply appropriate project management practices and techniques to build a “road map” to project implementation, control, and closeout.

All too often, when people think of project planning they perceive the use of only techniques and concepts such as PERT or CPM networking. These concepts are briefly discussed in this chapter. The footnote references can serve as useful guidelines in using PERT and CPM networking.6 These techniques are important to use in the development of a project schedule; however, project planning includes a much wider scope of activity. Such concerns as objective and goal setting, cost estimating and budgeting, scheduling, resource usage estimating, and specification of deliverables are key concerns. Project planning also involves a delineation of the organizational design to support the project as well as the information system and the control system, which are used to model, evaluate, and reallocate resources as required during the execution of the project plan.

Project planning deals with the determination of the activities and resources that have to be utilized to ensure that the project is adequately executed. Authority, responsibility, and accountability have to be planned so that members of the project team know what their specific roles are and how they relate to other members of the project team who are involved in executing work package activity. The following key questions need to be answered:

• When is the activity due?

• What is the time duration of each activity?

• What human and nonhuman resources are needed to execute each activity on the project?

• What are the estimated costs?

• How are the budget and financial plans to be established to support the cost considerations of the budget?

One of the changes under way in contemporary organizations is that more people are involved in and carry out the management functions.

Participative planning has been used effectively by AT&T. Participation is obtained through the use of workshops that include the entire project team and even customers in joint planning sessions. A planning process facilitator helps guide the activities and keeps the project planning moving forward. The purpose of these workshops is to have the participants agree on high-level project plans, schedules, and project monitoring and evaluation strategies. Held at the beginning of a project, the workshops achieve the benefits of early planning, including overcoming planning problems and getting the team members involved early in the planning, which leads to more commitment and dedication to their role on the project. In addition, team members are given an early exposure to their individual and collective roles in the project and an opportunity to identify any interpersonal anxieties that might hinder team development and operation at a later date. These start-up workshops have been successful in producing planning deliverables, developing planning skills, and building team interaction and cohesiveness.7

The project manager is responsible for initiating action to bring about the development of a plan. In discharging the project leadership role, the project leader has the final responsibility for ensuring that “the right things are done” about the project plan. The complexities of deciding what the details of the project should be and doing things right rest with the specialists, who are members of the project planning team. Planning becomes a method for coordinating and synchronizing the forthcoming project activities. Project planning should be undertaken after the project has been positioned in the overall strategy for the enterprise; then the detailed planning can be carried out with a high degree of assurance that the project planning team is working on the right areas.

Because planning involves thinking through the probabilities and possibilities of the project’s future, a detailed cookbook recipe for planning cannot be provided. However, certain key work packages and planning tools have to be addressed in the development of the project plan of action. These planning considerations are described in the next section.

13.8 WORK BREAKDOWN STRUCTURE8

The most basic consideration in project planning is the WBS. The WBS divides the overall project into work elements that represent singular work units, assigned either to the organization or to an outside agency, such as a contractor.

The WBS process is carried out in the following manner: Each project must be subdivided into tasks that can be assigned and accomplished by some organizational unit or individual. These tasks are then performed by specialized functional organizational components. The map of the project represents the collection of these units and shows the project manager the many organizational and subsystem interfaces to be managed.

The underlying philosophy of the work breakdown structure is to divide the project into work packages that are assignable and for which accountability can be expected. Each work package is a performance-control element; it is negotiated and assigned to a specific organizational manager, usually called a work package manager. The work package manager is responsible for a specific measurable objective, detailed task descriptions, specifications, scheduled task milestones, and a time-phased budget in dollars and workforce. Each work package manager is held responsible by both the project and the functional managers for the completion of the work package in terms of technical objectives, schedules, and costs.

The work breakdown structure is a means for dividing a project into easily managed increments, helping ensure the completeness, compatibility, and continuity of all work that is required for successful completion of the project. The WBS provides the basis for a fundamental understanding of the scope of the project and helps ensure that the project supports organizational objectives and goals.

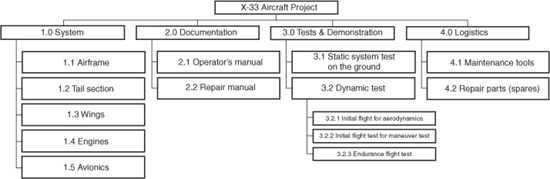

The process of developing the WBS is to establish a scheme for dividing the project into major groups, and then dividing the major groups into tasks, subdividing the tasks into subtasks, and so forth. Projects are planned, organized, and controlled around the lowest level of the WBS. The organization of the WBS should follow some orderly identification scheme; each WBS element is given a distinct identifier. With an aircraft, for example, the WBS might look like the information shown in Fig. 13.3.

FIGURE 13.3 Work breakdown structure coding scheme for an aircraft (example).

In the WBS, the decomposition of the aircraft includes both system components and the functions to support the project. The indenture at different levels indicates the components of that item. Decomposition is only done to the level at which the item will be managed.

A graphic representation of the WBS can facilitate its understanding. Using numerical listings with deeper indentation for successively lower levels can aid in communications and in developing understanding of the total project and its integral subsystems, sub-subsystems, and so forth. Figure 13.4 demonstrates the graphic approach to displaying the information.

FIGURE 13.4 WBS in a graphic diagram (example).

Work packages follow from a WBS analysis on the project. When the WBS analysis is completed and the work packages are identified, a WBS comes into existence. As shown in Fig. 13.4, a WBS can be represented similar to traditional organizational structure.

In the context of a project, the WBS and the resulting work packages provide a model of the products (hardware, software, services, and other elements) that completely define the project. Such a model enables project engineers, project managers, functional managers, and general managers to think of the totality of all products and services comprising the project as well as its component subsystems. The model is the focus around which the project is managed. More particularly, the development of a WBS provides the means for:

• Summarizing all products and services comprising the project, including support and other tasks

• Displaying the interrelationships of the work packages to each other, to the total project, and to other engineering activities in the organization

• Establishing the authority-responsibility matrix organization

• Estimating project cost

• Scheduling work packages

• Developing information for managing the project

• Providing a basis for controlling the application of resources on the project

• Providing reference points for getting people committed to support the project

Work packages are the goals to be accomplished on the project. There are certain criteria that should be applied to the project goals:

• Are they realistic?

• Are they specific?

• Are they time based?

• Are they measurable?

• Can they be communicated easily to the project team?

• Can they be clearly assigned to the work package managers/professionals?

The WBS provides a natural framework or skeleton for identifying the work elements of the project: hardware, software, documentation, and miscellaneous work to be accomplished to bring the project to completion. The WBS provides an identifier and a management thread to manage myriad aspects of the project. In some projects unique work packages are found. For example, in some international projects a cultural planning work package is included in the work breakdown structure. From this work package, successful cultural training and orientation can be carried out.

13.9 PROJECT SCHEDULES

A key output of project planning is the project master schedule, along with supporting schedules, which is a graphic time representation of all necessary project-related activities. The project schedule establishes the time parameters of the project and helps the managers to effectively coordinate and facilitate the efforts of the entire project team during the life of the project. A schedule becomes an effective part of the project control system. For a project schedule to be effective, it must be:

• Understandable by the project team

• Capable of identifying and highlighting critical work packages and tasks

• Updated, modified as necessary, and flexible in its application

• Substantially detailed to provide a basis for committing, monitoring, and evaluating the use of project resources

• Based upon credible time estimates that conform to available resources

• Compatible with other organizational plans that share common resources

Several steps are required to develop the project master schedule. These steps should be undertaken in the proper sequence.

• Define the project objectives, goals, and overall strategies.

• Develop the project work breakdown structure with associated work packages.

• Sequence the project work packages and tasks in a schedule.

• Estimate the time and cost elements.

• Review the master schedule with project time objectives.

• Reconcile the schedule with organizational resource availability.

• Review the schedule for its consistency with project costs and with technical performance objectives.

• Senior managers approve the schedule.

13.10 SCHEDULING TECHNIQUES

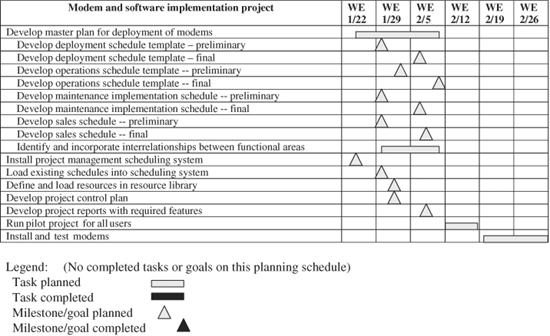

Several scheduling techniques are useful in dealing with the timing aspect of the project resources. The typical graphic illustration is the bar chart, whereas the networks for PERT (program evaluation and review technique) and CPM (critical path method) show the connectivity between work packages or activities.

Project Planning Bar Charts

A technique for simple project planning and scheduling is based on the bar chart (or Gantt chart, after Henry Gantt, one of the early users of a bar chart). This chart consists of a scale divided into units of time (e.g., hours, days, weeks, or months) across the top and a listing of the project work packages or elements down the left-hand side. Bars or lines are used to indicate the schedule and status of each work package in relation to the time scale. Figure 13.5 is an example of a project planning bar chart for the development of an electronic device.

FIGURE 13.5 Project planning bar chart.

The work packages of the project are listed on the left-hand side, and the units of time in weeks are shown at the top. Light horizontal lines indicate the schedule for the project elements, with the specific tasks or operations written above the schedule line. Work accomplished is indicated by a heavy line below the schedule line.9 The triangles represent milestones in the project.

Bar graphs are easy to develop and understand, and by showing the scheduled start and finish of the work packages they provide a simple picture of where the project stands. A variation of the bar chart is the milestone chart, which replaces the bar with lines and triangles to indicate project status. A bar chart might not show work package interdependence and time-resource trade-offs. Network techniques used on larger projects help plan, track, and control complex projects effectively.

Network Techniques

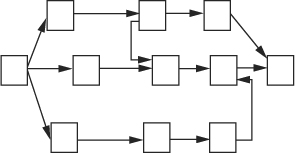

The network techniques known as PERT and CPM came out in 1956. The network diagram of PERT/CPM provides a more powerful picture of the work package relationships than either the bar chart or the milestone chart. The network diagram, basic to PERT/CPM techniques, provides a dynamic interrelated picture of the activities and interrelationships relative to the project. The main value of the network technique is its depiction of these relationships to show the sequence in which work is being executed. While PERT and CPM are excellent systems for summarizing work being tracked on a large project, they also aid in analysis of work during delays in one or more tasks during project execution.10 Figure 13.6 shows the basic characteristics of a PERT/CPM diagram.

This diagram shows nodes that represent connections for tasks, which are shown by arrows. The solid lines of connectivity between the nodes represent work, or tasks, to be completed. The broken lines of connectivity indicate constraints. A completed diagram would have a time on each arrow to represent the time duration required to accomplish the task. PERT uses three time estimates and computes the estimate as follows:

Time expected (Te) equals Optimistic time (O), plus four times Most Likely (ML), plus Pessimistic time (P), divided by six, or Te = (O + 4ML + P)/6.

This gives the resultant number a central tendency that does not cover the full range of options. For example, the actual time could be less than the optimistic or more than the pessimistic estimates.

The more common type of diagram being used in most projects today is the precedence diagram. Figure 13.7 depicts the precedence diagram. The precedence diagram is a critical path methodology and closely follows the CPM protocols. Its major difference is that the work is in the nodes rather than in the arrows. The arrows are connectors to the work and do not consume time. This diagramming method is more flexible than CPM/PERT in that no lines constrain the work like the dashed lines of CPM.

FIGURE 13.7 Precedence diagram.

Another advantage of the precedence diagram is that the connectivity can be arranged in the schedule through four relationships—finish-to-start, finish-to-finish, start-to-start, and start-to-finish. Each connectivity relationship has its advantages. However, the most common is the finish-to-start, or finish one activity and start another.

13.11 PROJECT LIFE-CYCLE PLANNING

The project life cycle is a key consideration in project planning. Project life cycles contain phases, or control mechanisms, to divide the project into different work efforts. The typical project life cycle has four phases: initiation, planning, execution and control, and closeout. These phase can be different to meet the needs of a specific industry and the names may differ. However, the concept is the same—divide the life of the project into manageable parts, each one representing a control point at the end.

Once the appropriate work packages for each phase of the project’s life cycle have been depicted, a substantial start has been made toward the development of the project plan. Figure 13.8 shows an example of how the work is to be accomplished by project phase. This model is also shown in Fig. 3.3 in a different context.

FIGURE 13.8 Tasks accomplished by project phase. [Source: John R. Adams and Stephen E. Brandt, “Behavioral Implications of the Project Life Cycle,” in David I. Cleland and William R. King (eds.), Project Management Handbook (New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold, 1983), p. 227.]

13.12 PROJECT PLANNING ELEMENTS

There are a few fundamental components in the project planning process. These elements include the outputs from the techniques and processes previously discussed as well as the elements discussed in the material that follows.

Statement of Work

A statement of work describes the actual work that is going to be performed on the project which, when combined with the specifications, usually forms the basis for a contractual agreement on the project. As a derivative of the WBS, the statement of work (sometimes called scope of work) describes what is going to be accomplished, a description of the tasks, and the deliverable end products that will be produced, such as hardware, software, tests, documentation, and training. The statement of work may also make reference to specifications, directives, or standards, that is, the guidance to be followed in the project work. The statement of work includes input required from other tasks involving the project and a key element of the customer’s request for a proposal.

Project Specification

Specifications are the descriptions of the technical content of the project. These specifications typically describe the product of the project and the requirements that the product must meet. Further, they contain the characteristics of the various subsystems in the project’s product or service, in order to include an overall system specification, hardware, software, test specifications, and logistics support.

Cost Estimate

The cost estimate forms the baseline budget from which all actual expenditures will be measured. Typically, the cost estimate follows the WBS during development and implementation. The type of cost estimate determines the precision associated with individual cost items.

Detailed cost estimates are expensive because of the time and labor effort required to perform the estimate. The less precise the estimate, typically, the less the cost that is associated with the estimate. The three types of cost estimates are as follows:

• Order of magnitude (–25%, + 75%). Used to make an initial estimate of a project for purposes of getting a rough idea of the cost. Note that the project may have a 100 percent variance, that is, 25 percent less or 75 percent more.

• Budget (–10%, + 25%). Used to perform a “tighter” estimate than can be used for decision making concerning whether the project is within the tolerances of the organization.

• Definitive (–5%, + 10%). Used to start a project based on solid planning and a good estimate of all parts of the project.

During implementation, the cost estimate forms the baseline for project expenditures and provides a means of comparing actual costs to the estimate. Projects may require weekly or monthly cost reports to reflect the actual expenditure as compared to the baseline estimate. An element of the cost system is a report, which provides weekly actual cost with estimated cost as well as a comparison of actual worker-hours with target worker-hours in manufacturing or construction.

The cost account usually is considered the basic level at which project performance is measured and reported. This account represents a specific work package identified by the WBS, usually tracked by information on a daily or weekly time card, which ties in with the organizational cost accounting system.

Financial Plan

Assuming that project budget, work package budget, and budgets for the appropriate cost accounts have been developed, financial planning involves the development of action plans for obtaining and managing the organizational funds to support the project through the use of the work authorization process.

The project manager usually authorizes the expenditure of resources on the project for work to be accomplished within the organization as well as on work subcontracted to vendors. The work authorization process is an orderly way to delegate authority to expend resources for the project. The work authorization document usually includes:

• The responsible individual and/or organization

• A WBS work package

• A schedule

• Cost estimate and funding citation

• A statement of work

Usually the work authorization document is in a one-sheet format that is considered a written contract between the project manager and the internal performing organization and/or person.

Functional Plan

Each functional manager should prepare a functional operations plan that establishes the nature an timing of functional resources necessary to support the project plan. For example, the accounting/financial organization that supports the project manager should establish a plan for how the project budget can be monitored. Such a plan would be an information system for monitoring actual project costs and comparing them with budgeted costs.

13.13 PLAN FORMAT

The organization and arrangement of the project plan depend on the nature of the project. The bare essentials of a project plan include:

• A summary of the project that states briefly what is to be done and the methods and techniques to be used. It lists the deliverable end products in such a way that when they are produced, they can be identified easily and compared with the plan.

• A list of tangible and discrete goals, identified in such a way that there can be no ambiguity about whether a goal has been achieved.

• A WBS that is detailed enough to provide meaningful identification of all tasks associated with job numbers, plus all higher-level groupings such as work units or work packages.

• A strategy outlining how organizational resources will be used to accomplish project objectives and goals.

• An activity network that shows the sequence of elements of the project and how they are related

• Separate budgets and schedules for all the elements of the project for which some individual is responsible.

• An interface plan that shows how the project relates to the rest of the world, most particularly to the customer.

• An indication of the review process: who reviews the project, when, and for what purpose.

• A list of key project personnel and their assignments in relation to the WBS.

13.14 PROJECT MANAGEMENT MANUAL

An important part of project planning is the development of organizational policies and procedures that support the project plan. Many organizations use a project management manual that tells all project participants what they have to do and how they have to do it.

The project management manual is the document that establishes standing procedures for project planning and implementation. When properly constructed, the project management manual covers aspects of the organization’s project management that are consistent across projects and programs. For example, it may state that all projects will have a formal review by senior management no less than once each quarter and once a month for projects that are experiencing difficulties.

13.15 PROJECT PLANNING WORK PACKAGES

Even the task of planning a project should be broken down into work packages. Here is a general guide to these work packages, not necessarily done in the sequence indicated:

• Establish the strategic fit of the project. Ensure that the project is truly a building block in the design and execution of organizational strategies and provides the project owner with an operational capability not currently existing or improves an existing capability. Identify strategic issues likely to affect the project.

• Develop the project technical performance objective. Describe the project deliverable end product(s) that satisfies a customer’s needs in terms of capability, capacity, quality, quantity, reliability, efficiency, and so on.

• Describe the project through the development of the project WBS. Develop a product-oriented family tree division of hardware, software, services, and other tasks to organize, define, and graphically display the product to be produced, as well as the work to be accomplished to achieve the specified product.

• Identify and make provisions for the assignment of the functional work packages. Decide which work packages will be done in-house, obtain the commitment of the responsible functional work managers, and plan for the allocation of appropriate funds through the organizational work authorization system.

• Identify project work packages that will be subcontracted. Develop procurement specifications and other desired contractual terms for the delivery of the goods and services to be provided by outside vendors.

• Develop the master and work package schedules. Use the appropriate scheduling techniques to determine the time dimension of the project through a collaborative effort of the project team.

• Develop the logic networks and relationships of the project work packages. Determine how the project parts can fit together in a logical relationship.

• Identify the strategic issues that the project is likely to face. Develop a strategy to deal with these issues.

• Estimate the project costs. Determine what it will cost to design, develop, and manufacture (construct) the project, including an assessment of the probability of staying within the estimated costs.

• Perform risk analysis. Establish the degree or probability of suffering a setback in the project’s schedule, cost, or technical performance parameters.

• Develop the project budgets, funding plans, and other resource plans. Establish how the project funds should be utilized, and develop the necessary information to monitor and control the use of funds on the project.

• Ensure the development of organizational cost accounting system interfaces. Because the project management information system is tied in closely with cost accounting, establish the appropriate interfaces with that function.

• Select the organizational design. Provide the basis for getting the project team organized, including delineation of authority, responsibility, and accountability. At a minimum, establish the legal authority of the organizational board of directors, senior management, and project and functional managers, as well as the work package managers and project professionals. Use the LRC (linear responsibility chart) process to determine individual and collective roles on the project team.

• Provide for the project management information system. An information system is essential to monitor, evaluate, and control the use of resources on the project. Accordingly, develop such a system as part of the project plan.

• Assess the organizational cultural ambience. Project management works best where a supportive culture exists. Project documentation, management style, training, and attitudes all work together to make up the culture in which project management is found. Determine the project management training that would be required. What cultural fine-tuning is required?

• Develop project control concepts, processes, and techniques. How will the project’s status be judged through a review process? On what basis? How often? By whom? How? Ask and answer these questions prospectively during the planning phase.

• Develop the project team. Establish a strategy for creating and maintaining effective project team operations.

• Integrate contemporaneous state-of-the-art project management philosophies, concepts, and techniques. The art and science of project management continue to evolve. Take care to keep project management approaches up to date.

• Design project administration policies, procedures, and methodologies. Administrative considerations often are overlooked. Take care of them during early project planning, and do not leave them to chance.

• Plan for the nature and timing of the project audits. Determine the type of audit best suited to get an independent evaluation of where the project stands at critical junctures.

• Determine who the project stakeholders are and plan for the management of these stakeholders. Think through how these stakeholders might change through the life cycle of the project.

If the project team follows the suggested development of the project planning work packages suggested in this chapter, it is probable that all the needed project planning will be carried out. As these project planning work packages are prepared, it is likely that planning initiatives not reflected in these work packages will be identified and can be planned for accordingly.

13.16 MANAGEMENT REALITIES

Complete plans are but a “best effort” of the planning team based on information and guidance received. The larger the project, the greater the chance that the plan will change through either new guidance or updated information being received. Plans are “living documents” that change as competitive and environmental systems change. Continual update of information and additional planning are typically required throughout the life of the project.

Implementation of plans requires that communications and coordination take on added emphasis. Teams, rather than fixed organizational structures, are the order of the day. Integration becomes supreme as organizational processes are crossed as needed, and when needed, pulls together synchronized and quality efforts to produce customer value.

For many managers, who grew up in a “command and control” culture, the new paradigm of “consensus and consent” management is disquieting. They will need to adapt to the new way of getting things done—that is, by sharing the decision making and power in the project. Managers have become the servants of those they choose to rule. This new world is concerned with flexibility in strategies, markets, projects, resources, and people.

In the past, we managed as if the optimization of the parts of the organization—research, manufacturing, engineering, marketing, product development, and so forth—would lead to the optimization of the whole of the organization. Today, we optimize the integration of the organizational processes by using project teams as focal points to pull together the human and nonhuman resources needed to do the job. The major breakthroughs in improving organizational efficiency and effectiveness have come about because of the management of the organizational processes rather than the functional entities of the organization. The management of the organizational processes through a self-directed team has finally captured the essence of the interdependencies of the organizational functions.

All planning efforts need to consider the new world and dynamic changes that occur, some on a daily basis. Planning does provide the framework and the thought process to visualize the work required to build a product or service that brings benefits to the customers. Planning also gives a foundation from which to initiate change, when required to meet new situations. No plan is perfect to carry one through an entire project, but a good plan does provide a path from which one can adjust to meet the changes.

13.17 PROJECT PARTNERING11

Partnering in projects has emerged in recent years as a means of sharing equally in managing large projects by two or more organizations. One organization may initiate partnering to gain additional capability for a project as well as share in the risks of large complex projects. Partnering is also a means of combining information, such as in research and development projects, to improve the chance of success.

Partnering may be accomplished between public, private, and for-profit and not-for-profit organizations. A government agency may, for example, partner with a private organization to conduct research. Another example is for a private for-profit professional association to partner with a not-for-profit company to develop a commercial product from intellectual property.

There is no limit to project partnering by organizations. A common goal and complementing capabilities are the basis for a project partnership. Finding the talent needed to perform specific project work and developing cooperative arrangements for the partnering are needed for a working partnership.

13.18 TYPES OF PROJECT PARTNERING ARRANGEMENTS

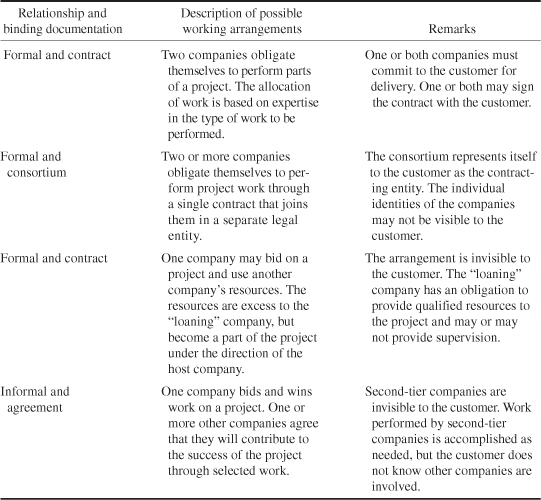

Project partnerships may take many forms of cooperative agreements. The formality and contractual relationship are determined by the needs of all partners. Some examples of these relationships are depicted in Table 13.2.

TABLE 13.2 Types of Project Partnering Arrangements

The number of arrangements is left to the organizations desiring to partner and work together. One important aspect is for the visibility that the customer has of the accomplishment of different work packages. In some partnering, the customer wants to be aware of who is doing the work, and in other situations, the customer is only concerned with the quality of the work.

13.19 EXAMPLES OF PROJECT PARTNERING ARRANGEMENTS

There are many examples of project partnering that demonstrate the concept and the future of this type of business relationship. Figure 13.9 shows several examples of project partnering.

FIGURE 13.9 Examples of project partnering.

• Engineering and construction firms partner to obtain the best mix of talent and capability for projects. Partnering to obtain excellence in project control for major projects is often found in major projects such as the Super Collider Project in Dallas, Texas.

• Aerospace companies partnered to build a stealth bomber on a $4 billion project. Several companies worked together to develop the best in stealth technology.

• Three small companies combined their capabilities to bid and win a project requiring expertise in computer technology, computer network operations, and procurement knowledge.

• Licensing of intellectual property of a professional association to a company to build software products is a current project. The association’s standards were licensed to a company for the specific purpose of expanding the distribution of knowledge in the standards and to generate a modest profit for the association.

13.20 MANAGING PARTNERED PROJECTS

Customers are concerned with the management of the project work and who will be responsible for such items as reports, corrective actions, changes to the project, and overall project direction. Strong management capability builds confidence with the customer, whereas a weak or vague project management structure erodes confidence. Figure 13.10 shows typical types of arrangements for managing partnered projects. A discussion follows.

FIGURE 13.10 Managing partnered projects.

Some management structures for partnered projects are:

• Steering committee. Senior managers from all partnering organizations. This committee reviews progress and sets direction. A project manager or co-project manager is designated for all partnered work and reports to the steering committee.

• Project manager and deputy project manager (or co-project manager). Two individuals are designated from the partnering companies to lead the project. These individuals may report to their respective company executives or to a steering committee.

• Project manager. A single individual is appointed as the project manager for all the project work. Project team members report to the project manager on performance issues.

These three management structures can be modified to meet any situation. Large projects need senior guidance from a group such as a steering committee, whereas small projects would only require a single project manager.

13.21 TECHNICAL ASPECTS OF PARTNERED PROJECTS

One of the primary reasons for partnering is to gain additional technical capability. A customer wants assurances that the project will be technically successful and that the performing organization has the capability to accomplish the work. Partnering gives that assurance by bringing the best talent from more than one company.

Strategies of partnering will guide companies to better work solutions and better products for the customers. The following is a list of sample strategies:

• Work allocation. Divide work so the work packages are performed with an integral team when possible.

• Project control. A team could be assigned responsibility for controlling the project work. This team may be individuals from different companies, but should have clear work responsibilities.

• Project management. There needs to be a single person responsible for managing the work. Some work may be performed under the supervision of a manager, but that manager is responsible to the project manager for delivering a product component.

• Company participation. Company managers must not, as individuals, become involved in the direction of the project. Direction must be through a consolidated body, such as a steering committee or senior management representative group.

• Customer interface. Like any project, partnered projects must have a single interface with the customer. This may be the project manager, the chair of the steering committee, or the elected representative from the management group. In some situations, there are two levels of customer interface. The strategic direction and liaison are from the senior steering committee and the daily interface is between the project manager and the customer’s representative.

13.22 PARTNERING CHALLENGES AND BENEFITS

Project partnering takes on many forms based on the desires and creativity of the partners. The arrangements will vary according to the project and the visibility of organizations may be more or less, depending on the needs for the partnered project. Organizations, public and private, for-profit and not-for-profit, can create partnerships to meet the needs of a small, medium, or large project.

Managing a partnered project is typically driven by the desires of the customer. Customer confidence and visibility into the project dictate the management approach as well as the size of the project. It is not uncommon to have a two-tier management structure, that is, a project manager and a steering committee to which the project manager reports.

Many benefits are derived from partnered projects. These include learning from other organizations’ management and technical processes, obtaining technical knowledge about project management methodologies and processes, acquiring improved work methods from others and large profit shares through improved productivity.

13.23 OUTSOURCING PROJECT MANAGEMENT12

Outsourcing, or out-tasking as some organizations call it, is a growing field. Historically, the soft areas such as custodial services, food services, and landscaping have dominated the outsourced work; nearly 50 percent of recently surveyed organizations identify these areas. Maintenance of fleet automobiles and aircraft are also examples of areas for outsourcing.

Outsourcing is contracting for services that could be provided by the organization, if the organization had the capability and desire to perform those functions. Outsourcing has many advantages in that it is typically more economical to buy the products and services than provide them in-house. There is no investment in the function in terms of people, equipment, or maintenance for the outsourcing organization.

At GE, under the banner of “no back offices,” CEO Jack Welch told managers to digitize or outsource the pants off their business that didn’t touch the customer.13 Outsourcing of core competencies is not recommended because an organization loses its capability to function effectively. Core competencies must be nurtured and grown rather than contracted for through another organization. A providing organization has little incentive to improve on another organization’s core competencies as long as the products and services are being purchased.

13.24 PROJECT MANAGEMENT AS AN OUTSOURCED SERVICE

Project management services have been outsourced in several instances and the future looks promising for more outsourcing. The benefits of outsourcing project management include improved and more economical operations.

Project management services can be improved by transferring the functions to an organization specializing in project management. This specialized company hires the right skills and uses the best of practices because it is their core competency. They have resources that focus on providing these services and have the in-depth expertise to perform at high-performance levels.

Outsourcing relieves the parent company of the burden of managing project management services. Through contractual relationships, the parent company states its needs and then manages the contract and delivery of services. There is less effort required to receive the products and services from outsourced project management than to manage it in house.

Outsourcing companies may be concerned with loss in the project management function. Organization outsourcing will lose visibility into the details of work, but there is no need to see detail when the end product meets the requirements. Outsourcing companies should only be concerned with the delivered product and less concerned over the details of production.

13.25 OUTSOURCING TRENDS

Project management outsourcing has been primarily one of providing services to organizations by one person at a time. It is referred to as “body shop” or “hired gun” because the project management professional is typically working on-site with the organization’s staff. This type of arrangement is profitable for the organization doing the work, but is not outsourcing.

The “body shop” or “hired gun” approach mixes different levels of proficiency and competency. The lower level of project management proficiency and competency is typically the resident employee of the organization and the outside person brings the expertise. This places the resident employee as the driver and the expert as the follower. There is considerable waste in talent, time, and money with this approach.

Outsourcing of project management services will, like other professional services, continue to be used to fulfill the needs of organizations. This has a high-growth potential because of the ability of project management service providers to deliver better products in a timely manner at lower cost. Project management service providers will have the expertise and skills to build better products than a part-time effort in-house.

13.26 SELECTING AN OUTSOURCE PROVIDER

Successful selection of an outsource provider is accomplished in four sequential steps. These steps give a high degree of assurance that the best provider is selected and that the outsourcing relationship is satisfactory. Figure 13.11 graphically displays the steps.

FIGURE 13.11 Selecting an outsource provider.

• Conduct an internal analysis. Identify those functions that can be outsourced, assess the tactical and strategic impact of outsourcing each identified function, evaluate the total cost of each function selected for possible outsourcing, and determine the advantages and disadvantages of outsourcing. Classify each function as “no outsourcing,” “possible outsourcing,” and “definite outsourcing.” Use criteria for each category such as listed in Table 13.3.

TABLE 13.3 Criteria for Outsource Provider Selection

• Establish a relationship with providers. Issue a request for information (RFI) that solicits interest in providing products/services, select two or three respondents, and ask for due diligence. Conduct a due diligence survey to validate the capabilities of the potential providers.

• Establish a contract. From the three respondents meeting the due diligence survey criteria, negotiate a contract with one. Establish scope and boundaries for the contract and describe the following:

• Resources to be used to produce the products and services

• Key deliverables and the schedule for delivery

• Performance measures and other quality metrics

• Invoice and payment schedule to include provisions for timing of payments

• Change and termination provisions of the contract

• Administer the outsourcing relationship. Establish the contract management process, establish the technical review process, establish a change order process, and establish a steering committee or oversight committee. Involve the users or consumers of the products and services in the steering/oversight committee.

Identifying providers who can meet the organization’s needs involves more than establishing a contract and working to enforce the provisions and clauses. A good contract is the basis for promoting understanding with the provider of products and services. It is also essential that the provider have a record of meeting contract provisions.

References should be checked during due diligence and references should be asked the following questions:

• Did the contractor deliver the products and services called for in the contract?

• Were the products and services usable by the consumer as delivered?

• Did the contractor demonstrate flexibility in minor changes to the contract or was each minor change an issue?

• Were change orders to the contract performed on a fair and equitable basis?

• Do you recommend the contractor for these products and services?

• Would you award a contract to this contractor again?

13.27 OUTSOURCING PROJECT MANAGEMENT SERVICES AND PRODUCTS

From an organization’s perspective, there is a need to determine what may be outsourced and to which project management service provider. First, the areas of project management that may be outsourced need to be identified. Second, identify the best provider.

Project management products and services that may be outsourced depend upon the organization’s structure for project management, the degree of maturity in project management, the number of projects, and the management style. The organization must know what is needed in terms of project management products and services. An organization with a loosely structured project management capability may not know what is needed.

The entire project may be outsourced. This frequently happens within such fields as information technology or information systems where the organization only wants to be concerned with software solutions and not the challenges of designing, developing, testing, and delivering software releases. When only components of project management are outsourced, Table 13.4 may be helpful.

TABLE 13.4 Outsourcing by Project Management Component

13.28 PROJECT MANAGEMENT OUTSOURCING GUIDELINES

Outsourcing for any products and services needs to consider all aspects of the relationship and how it is managed. Transition of the responsibility for products and services must be coordinated and performed according to an agreed-upon plan. The following items are helpful in guiding an organization through outsourcing of project management services and products.

• Products and services. Identify the products and services to be transitioned (or initiated if there are no current comparable in house). Describe the products and services in detail and conduct a mutual understanding meeting to ensure both parties have full agreement on the products and services.

• Standards and formats. Identify the standards and formats that are considered a requirement. Standards and formats provide a consistency to the delivered products, but will change the current in-house products.

• Frequency of delivery. Determine the frequency of delivery for products and time required for preparing products. Typically, reports are provided on a weekly basis, but there may be requirements for rapid turnaround for some products.

• Method of delivery. Products may be delivered in hard copy, electronic copy, or a combination of these. Determine the most appropriate and effective means of delivery for all products.

13.29 OUTSOURCING POTENTIAL

Outsourcing project management products and services has the potential for significant gains for an organization. Outsourcing relieves the outsourcing organization of a technical area for which they may not have the trained resources to perform and to perform at a lower cost. Outsourcing can place many of the project management functions in the hands of project management professionals.

Entering into an outsourcing arrangement requires some background work to identify and select the provider with the best qualifications and reputation as a contractor. The time and effort spent on selection of the provider will save effort in managing the relationship.

13.30 TO SUMMARIZE

The major points that have been expressed in this chapter include:

• Project planning involves the development of a strategy for the commitment of resources to support the project objectives and goals.

• There is a high degree of interdependence among the strategic plan, functional plans, and project plans of the enterprise.

• Project planning is a rational determination of how to initiate, sustain, and terminate a project.

• Planning starts with the ability to sense and develop a vision involving the ability to see something that is invisible to others.

• Without a vision, the project may very well deteriorate and fail.

• An organizational mission is a summary statement of the “business that the enterprise is in,” and projects are the way the business is conducted.

• Organizational objectives are ongoing end purposes of the enterprise.

• A project goal is a milestone for the project.

• A project strategy is the design of the means, through the use of resources, to accomplish end purposes.

• A project is more than a schedule and a spending plan; it is an integrated effort to produce a product, service, or organizational process change.

• The quality and quantity of the organizational resources constitute the common denominator of planning, as well as the competencies of the enterprise and the projects involved in that enterprise.

• The roles of people regarding their project planning responsibilities were indicated.

• There are several specific project planning techniques that were briefly described in the chapter with references to more extensive literature on these techniques.

• The work breakdown structure (WBS) is the most basic consideration in project planning. The key reasons for using a WBS were described in the chapter.

• The general nature of a project schedule was noted in the chapter along with some general guidelines on the processes to be followed in developing a project schedule.

• A guide for project planning was presented in the chapter with examples of techniques.

• An important part of project planning is a consideration for partnering and outsourcing.

13.31 ADDITIONAL SOURCES OF INFORMATION

The following additional sources of project management information may be used to complement this chapter’s topic material. This material complements and expands on various concepts, practices, and theory of project management as it relates to areas covered here.

• John R. Adams and Miguel E. Caldentey, “A Comprehensive Model of Project Management,” Chap. 6, and Thomas C. Blanger and Jim Highsmith, “Another Look at Life Cycles,” Chap. 7 in David I. Cleland (ed.), Field Guide to Project Management, 2nd ed. (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, 2004).

• Gregory T. Haugan, Effective Work Breakdown Structures (Vienna, VA: Management Concepts, 2002). This book is a practical description of the work breakdown structure and its application to project work. It is designed for use by project planners and schedulers as well as the project team to provide a realistic guide to defining the project’s scope.

• Dragan Z. Milosevic, Project Management Toolbox: Tools and Techniques for the Practicing Project Manager (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, 2003). The author addresses the requirements for scope planning, schedule development, and cost planning in Chaps. 5, 6, and 7. This comprehensive treatment of project parameter planning and implementation demonstrates the techniques that might be applied to any project.

• James P. Lewis, Project Planning, Scheduling, and Control, 4th ed. (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2005). The author provides a step-by-step guide to planning and managing projects in a real-world environment. The book makes clear the process and practice of project planning techniques and tools.

• Albert Lester, Project Planning and Control, 4th ed. (London: Elsevier Science & Technology, 2004). The author brings forth the principles and practices of project planning and control that include translation of theory to practical application of techniques. The book contains actual case studies for the reader to assimilate the realism of project management.

13.32 DISCUSSION QUESTIONS

1. What are some of the basic concepts involved in project planning? How can a complete project plan contribute to project success?

2. Define each of the key elements of project planning.

3. Discuss the relationship of project planning to strategic planning and functional planning. Why is this relationship important?

4. List and discuss some of the traditional and modern planning practices.

5. Nearly all project stakeholders have some role in the project planning process. How are each of the key people afforded the opportunity to participate in project planning?

6. Describe a simple project management situation from your work or school experience. Develop a work breakdown structure for the situation.

7. What are some of the characteristics of an effective project schedule? Describe some of the scheduling techniques used in project management.

8. What are the relationships between the statement of work, project specification, cost estimate, financial plan, functional plan, and implementation plan? How is each developed and used?

9. List and describe the project planning work packages.

10. What is the purpose of a project management manual? How does it support the project plan?

11. Discuss the nature of the relationship between effective planning and effective control. What are some of the elements of each?

12. Discuss the following statement: Project planning is the most important work carried out by a project team.

13.33 USER CHECKLIST

1. Are the key elements of organizational planning mission, objectives, goals, strategies, and so forth evident in your organization? Is project planning linked to strategic planning? Explain.

2. Which project planning practices are used by your organization? How?

3. What role does each of the project stakeholders on projects within your organization play in the project planning process?

4. Do the project managers in your organization understand the concept of a work breakdown structure? Are work breakdown structures developed for every project? Why or why not?

5. How are project schedules developed? What scheduling techniques are used? Are these techniques effective? What other techniques might be more effective for project planning in your organization?

6. Is the project life cycle understood by the project managers in your organization? How is this concept integrated into the project planning process?

7. Which project planning elements (e.g., statement of work, project specification, cost estimate, financial plan, functional plan) are used by your organization? Which are not? Explain.

8. Are organizational policies and procedures developed to support the project planning? Would the development of a project management manual increase the effectiveness of the project planning process in your organization?

9. Do managers consider the strategic fit of projects to ensure that the project is truly a building block in executing organizational strategies? Explain.

10. Consider the project planning work packages. How do these work packages fit in your project planning?

11. How are the work packages assigned on major projects? Does management consider subcontracting work packages? Are logic networks and relationships developed for the work packages?

12. Is the cultural ambience of the organization supportive of rigorous project planning?

13.34 PRINCIPLES OF PROJECT MANAGEMENT

1. Planning projects is a critical function of project managers or leaders.

2. Planning projects will result in a plan that typically will require some change because of new information or a change to the basic requirements.

3. Planning projects is a top-down activity that pulls information from the organization as well as the project’s goals and objectives directly related to the expected benefits.

4. The quality of project planning relates directly to the chance of success for the project.

5. All plans will require revision to meet emerging changes and new information updates.

13.35 PROJECT MANAGEMENT SITUATION—DEVELOPING A PROJECT PLAN

An organization that builds aircraft controls has received a request for proposal (RFP) to bid on the manufacture and sale of 10,000 aircraft cabin temperature controls. The RFP has a statement of work and a technical specification that details what is required and to what standards. There is no drawing or design that details the temperature control mechanism, but the specification gives the space allocated for the mechanism, power requirements, durability requirements, and reliability requirements.

A decision has been made that a proposal will be submitted. However, the competition is expected to have a control that requires only a small amount of modification to meet the client’s requirements. Therefore, this job will be a project that must be planned to optimize all cost, schedule, and technical performance parameters.

Management has the following questions and guidance:

• How much will it cost for the project in total and what will be the average cost per unit?

• How long will it take to establish a design that meets or exceeds the specifications?

• How long will it take to build and deliver 10,000 units?

• What are the chances that the client will change the requirements after reviewing our design?

• What is our capability to start the project within 30 days following award of the contract?

• Give me a summary project plan before we submit our bid.

• Give me your answers and the plan in 2 weeks.

The prospective project manager is tasked with developing the summary project plan and the questions are to be answered by the functional managers. Coordination among the managers is essential to ensure that senior management gets the best single report.

13.36 STUDENT/READER ASSIGNMENT

1. As the project manager, what elements would you include in a summary project plan?

2. What type of cost estimate will be appropriate for the senior decision maker and why?

3. What type of schedule would be included in the summary project plan, if any?

4. What resource requirements are needed for the summary project plan and why?

5. What type of project organization should be considered for the summary project plan?