CHAPTER 2

WHY PROJECT MANAGEMENT?

“There is nothing permanent except change.”

HERACLITUS OF GREECE, 513 B.C.

Rogers’ Student’s History of Philosophy

2.1 INTRODUCTION

It has been said that there is nothing as powerful as an idea whose time has come. Project management, an evolving field of theory and practice, has emerged slowly as the field of management has come forth. Since the 1950s there has been acceleration in the development of the theory, literature, and practice of project management. Today there is a sufficient body of knowledge about project management so that this discipline has taken an important position in the lexicon of management and in the practices of modern organizations.

The evolution of project management from organizational liaison devices will be explored. In addition a preliminary philosophy of the discipline will be offered. As a mark of the growing maturity of project management, a description will be provided of the Project Management Institute, the commanding professional society in the field. The narrative of the chapter starts with a definition of just what a project is, followed by the way in which projects reflect how past societies have coped, in part, with changes in their environment.

This is a book about project management, a “field of study” and practice that has evolved over centuries and now promises to take its rightful place in the lexicon of management and in contemporary organizations. In this chapter, the overall concept of a project will be presented along with some examples of contemporary projects.

Just what is a project? Two early definitions are helpful. For example, it is “any undertaking that has definite, final objectives representing specified values to be used in the satisfaction of some need or desire.”1

Newman, Warren, and McGill defined a project and described its value as

simply a cluster of activities that is relatively separate and clear-cut. Building a plant, designing a new package, soliciting gifts of $500,000 for a men’s dormitory are examples. A project typically has a distinct mission and a clear termination point.

The task of management is eased when work can be set up in projects. The assignment of duties is sharpened, control is simplified, and the men who do the work can sense their accomplishment.

[A project might be part of a broader program, yet the] chief virtue of a project lies in identifying a nice, neat work package within a bewildering array of objectives, alternatives, and activities.2

The authors define a project as a combination of organizational resources pulled together to create something that did not previously exist and that will provide a performance capability in the design and execution of organizational strategies. Projects have a distinct life cycle, starting with an idea and progressing through design, engineering, and manufacturing or construction, through use by a project owner.

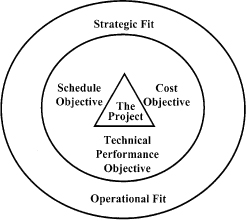

Four key considerations are always involved in a project:

• What will it cost?

• What time is required?

• What technical performance capability will it provide?

• How will the project results fit into the design and execution of organizational strategies?

The questions noted above must be answered on an ongoing basis for each project in the enterprise that is being considered, or for projects on which organizational resources are being used. The answers to these questions must also be evaluated in the context of the project’s fit into the organization’s operational (short-term) or strategic (long-term) strategies. Figure 2.1 portrays these considerations.

FIGURE 2.1 Interrelationships of project objectives and organizational fit.

Project management and strategic management are highly interdependent. In the material that follows, this interdependence will be presented.

2.2 THE ROLE OF STRATEGIC PLANNING

Strategic planning deals with the futurity of current decisions. This means that strategic planning considers the probable chain of cause and effect consequences over time of an actual planned decision. In the process of strategic planning, alternative courses of action (projects) that are possible in the future, and when choices are made among the alternatives, they become the basis for the selection of appropriate projects in the organization’s portfolio of projects.

There can be no formal strategic planning in an organization where the CEO does not understand the process, and has a deep appreciation of the role that projects play in bringing about change in the organization. As the organization grows in size, the CEO should delegate responsibility for strategic planning to the major organizational unit managers. However, the CEO always retains the full responsibility for the overal1 strategic direction of the enterprise.

2.3 THE SPIRIT OF STRATEGIC PLANNING

The insightful Spanish Jesuit Baltasar Gracian almost four centuries ago captured the spirit of modern strategic planning in a manner fitting to set the tone for the process in any organization:

Think in anticipation, today for tomorrow, and indeed. for many days. The greatest providence is to have forethought for what comes. What is provided for does not happen by chance, nor is the man who is prepared ever beset by emergencies. One must not, therefore, postpone consideration till the need arises. Consideration should go before hand. You can, after careful reflection, act to prevent the most calamitous events. The pillow is a silent Sibyl, for the sleep over questions before they reach a climax is far better than lying awake over them afterward. Some act and think later—and they think more of excuses than consequences. Others think neither before nor after. The whole of life should be spent thinking about how to find the right course of action to follow. Thought and forethought give counsel both of living and on achieving success.3

2.4 SOME LIMITATIONS OF FORMAL STRATEGIC PLANNING

1. The environment that the enterprise faces may change more than expected, including unexpected events in economics, social issues, war or the threat of war. The growing threat of terrorism, natural catastrophes like the Katrina hurricane.

2. Resistance by enterprise people. The old way of doing things, old policies, old strategies, and operating processes and procedures may be so entrenched that it is difficult to change them.

3. Strategic planning is challenging. It is hard work, expensive, and the desired results may take years to come about.

4. Formal strategic planning is not designed to get an enterprise out of current difficulties. But a strategic planning process that has considered alternative scenarios, both positive and negative, will help to reduce the effects of operational difficulties.

5. Strategic planning is hard work. It requires imagination, innovation, analytical ability, creativity, and the resolution to evaluate, choose, and design implementation strategies for organization products, services, and processes likely to be relevant several years into the future.

6. Strategic plans are commitments made in the present for alternative choices for the often distant future. A strategic plan should be a “living document” not allowed to become fixed for the future, but be a plan whose implementation is likely to come about assuming that environmental factors remain relatively constant.

2.5 STRATEGIC MANAGEMENT—THE PROJECT LINKAGES

One of the areas of management this book addresses is the strategic context in which projects are found in contemporary enterprises. In the material that follows, choice elements are found in the theory and practice of strategic management—the management of the enterprise as if its future mattered. A key choice element of strategic management is the emerging projects that are building blocks in the design and execution of strategies for the enterprise’s future.4

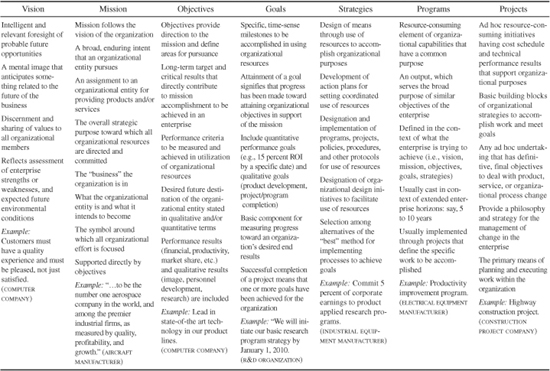

In the management of an enterprise as if its future mattered, nine key choice elements are involved. These choice elements for the enterprise are:

• Vision

• Mission

• Objectives

• Goals

• Strategies

• Programs

• Projects

• Operational plans

• Organizational design

These choice elements provide for the major performance standards by which enterprise resources will be identified, selected, committed, and reviewed in the enterprise for survival and growth in its future products, services, and organizational processes. These choice elements are defined as follows and portrayed in Table 2.1 and Fig. 2.2.

TABLE 2.1 Taxonomy of Choice Elements

FIGURE 2.2 Choice elements of strategic management.

Vision

A vision is a mental image of what could be anticipated for the enterprise’s future—such as becoming a world-class competitor. One company defined its vision to be a “world-class competitor—and to keep it that way.… We have programs in place to do just that such as a total quality management process whereby we live quality.” Another company included in its vision statement: “We will enhance our competitiveness by being first in the development of advanced technology that supports our world-class products and services.”

A telecommunications company conceived its vision in the following fashion: “As we enter the new millennium, AT&T is successfully transforming itself from a domestic long distance company to an any-distance, any-service global company. We’ve made the right strategic decisions, invested in the right assets, and have the right people to get the job done.”5

Mission

The mission of an enterprise answers the basic question: What business are we in? One project-driven firm defined its mission in the following way: “We are in the business of designing, developing, and installing energy management systems and services for the domestic industrial market.” The Boeing Company, which uses project management widely, describes its mission in the following fashion: “To be the number one aerospace company in the world, and among the premier industrial firms, as measured by quality, profitability, and growth.” Boeing uses projects as building blocks in the design and execution of strategies to fulfill its mission.

Objective

An objective is a statement of the ongoing purposes in the enterprise that must be carried out to support the organizational mission. A computer company defines one of its objectives as “leading the state-of-the-art in its products and services.” Another company defines its objectives as achieving a compounded earnings growth rate of 15 percent and a 20 percent return on capital. The major part of this strategy is to be the leader in providing scientists and educators worldwide with laboratory product and service systems created through technology, integrity, and a commitment to excellence. Objectives directly support the enterprise’s mission. Thus a failure to maintain an organizational objective can put the accomplishment of the enterprise’s mission in jeopardy.

Goal

A goal is a specific achievement in the satisfaction of enterprise objectives. As a performance measurement for progress in the use of resources to support corporate purposes, a goal has a specific time element. One company defined its goals as the realization of a certain percentage of return on invested assets by a specific date. Another company stated one of its principal goals as follows: “We intend, by the end of 1999, to complete the construction of a new manufacturing facility, which will complete the transition begun in 1997 from a predominately R&D services company to an industrial manufacturer.”

Further distinction between an objective and a goal is offered. An objective is an aspiration to be working toward on a continuous basis. A goal is an achievement to be realized in future times. Further differentiation between these two terms can be distinguished using a few measures:

• Time frame An objective is timeless and unending; a goal is time-based and intended to be overrun by subsequent goals.

• Specificity Objectives are usually stated in general terms, dealing with the attainment of desirable conditions in the future. A goal is much more specific, stated in terms of a particular result to be expected at a specific time point. Objectives are open-ended, and are sought on a continuous basis, regardless of the time element. Goals are milestones.

• Focus Objectives are usually stated in terms of some ongoing achievement in a relevant external environment, whereas goals are internally focused, whose achievement can be measured by a selected date. Objectives are often stated in the context of achieving leadership or recognition in certain desirable conditions for the enterprise. A goal implies a specific resource commitment to be used by a certain date.

• Measurement Both objectives and goals can be stated and measured in quantitative terms or qualitative terms. A company that states one of its objectives in terms of “achieving a compound rate of growth in earnings per share, placing its performance in the top 10 percent of all corporations” may attain that benchmark in 1 year, but it is timeless and means that the ensuing years must reflect the same performance unless changed. A goal that is quantified is expressed in absolute terms—a president of a company could state that the enterprise would “achieve half of its sales revenue from a particular industry by 2002.” The achievement of that goal can be specifically measured. Once attained, the goal would be restated for the ensuing year.

• Organizational goals and projects are inextricably interwoven The successful completion of a project means that an organizational goal has been achieved, which in turn means that progress has been made toward the realization of the enterprise’s objectives and mission. When a project is behind schedule, or overrunning costs, or unlikely to attain its performance objective, the enterprise’s objectives and mission could be impaired.

Strategy

An organizational strategy is the design of the means, through the use of resources, to accomplish end purposes. Strategies also include action plans for establishing the direction for the coordinated acquisition and use of resources through organizational design choices. Strategies also provide for the means to obtain resources for the enterprise, and how to use such resources effectively and efficiently in the fulfillment of organizational purposes.

Programs

Programs are resource-consuming combinations of organizational resources, which have a common purpose in supporting the enterprise’s purposes. For example, a productivity improvement program could be composed of projects such as the following:

• The use of self-managed production teams on the assembly line

• Plan and equipment modernization initiatives

• Use of computer-aided design and manufacturing

• Changeover of a production facility from conventional manufacturing to manufacturing cells

A capital investment program would consist of a number of new projects such as improved equipment development, new facilities, acquisition of equity or debt funding initiatives, and training of personnel.

Projects

Projects are ad hoc, resource-consuming activities used to implement organizational strategies, achieve enterprise goals and objectives, and contribute to the realization of the enterprise’s mission.

Operational Plans

Operational plans are those documents developed to guide the organization in a consistent fashion toward meeting its mission, objectives, and goals through designated strategies. These plans form the overarching policies, procedures, and practices for when and how program and project work will be accomplished.

Organizational Design

Organizational design is the organizational structure that facilitates performing the work. Organizational design considers the business that is being conducted, the manner in which work will be conducted, the practices for managing the work effort, and strategies for work accomplishment. An optimal organization design supports the enterprise in getting its work accomplished in the most competitive way.

2.6 PROJECTS

Projects have played a key role in some instances and have initiated changes in the societies of antiquity that are still being felt today. A few of these projects are cited and portrayed in the material that follows:

1. An early explorer, Amerigo Vespucci, was in project work and indeed could be called a “project manager.” In 1501, commanding three caravels, he arrived at a new land, which he called a “new continent.” What he did was follow the South American coast for about eight hundred leagues, which took him well down into Patagonia, near the present San Lulian, only some four hundred miles north of the southern tip of Tierra del Fuego. The new continent that Vespucci discovered was not named by himself. Rather the name America came from the efforts of Martin Waldseemiller (1410–1518), an obscure clergyman, who had studied at the University of Freiburg. In one of Waldseemiller’s books, Cosmoqraphiae Introductio, which summarized the traditional principles of cosmography, he observed that “Inasmuch as both Europe and Asia received their names from women, I see no reason why any one should justly object to calling this new land Amerigo (from Greek “ge” meaning “land of,” the land of Amerigo, or America, after Amerigo, its discoverer, a man of great ability.”6

2. The “project” to discover the cause and the cure of yellow fever was surely one of the health challenges of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Yellow fever had killed thousands of victims in epidemics that raged in tropical and coastal cities, especially in the Caribbean. Walter Reed (1851–1912) was an American army surgeon, who went to Cuba in 1900 to investigate an outbreak among U.S. soldiers. By intentionally subjecting volunteers to bites, he proved that, like malaria, yellow fever was carried by mosquitoes, not people. The success of his research efforts on this project is best described in a letter Walter Reed wrote to his wife:

Columbia Barracks, Quesmados, Cuba, December 9, 1900 It is with a great deal of pleasure that I hasten to tell you that we have succeeded in producing a case of unmistakable yellow fever by the bite of the mosquito. Our first case in the experimental camp developed at 11:30 last night, commencing with a sudden chill followed by fever. He had been bitten at 11:30 December 5th, and hence his attack followed just three and a half days after the bite. As he had been in our camp 15 days before being inoculated and had had no other possible exposure, the case is as clear as the sun at noon-day, and sustains brilliantly and conclusively our conclusions. Thus, just 18 days from the time we began our experimental work we have succeeded in demonstrating this mode of propagation of the disease, so that the most doubtful and skeptical must yield. Rejoice with me, sweetheart, as aside from the antitoxin of diphtheria and Koch’s discovery of the tubercle bacillus, it will be regarded as the most important piece of work, scientifically, during the 19th Century. I do not exaggerate, and I could shout for very joy that heaven has permitted me to establish this wonderful way of propagating yellow fever.… Major Kean says that the discovery is worth more than the cost of the Spanish War, including the lives lost and money expended.7

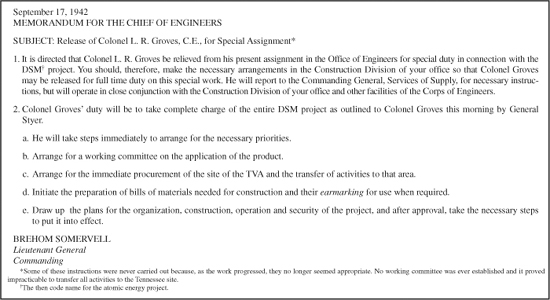

3. The Manhattan Project for the development and delivery of the atomic bomb was put under the charge of General Leslie R. Groves for the period September 17, 1942, through December 31, 1946. There was, according to General Groves, a “cohesive entity” that was the Manhattan Project, a factor in its success. The memorandum of appointment for General Groves (Colonel Groves) is shown in Fig. 2.3. The organization chart that identifies the position of General Groves in May 1945 is shown in Fig. 2.4.

FIGURE 2.3 Appointment memorandum for Colonel Groves to the Manhattan Project.

FIGURE 2.4 Organization chart of the Manhattan Project, May 1945.

Much has been discussed about the importance of the use of the atomic bomb as a key strategy in the U.S. pursuit of World War II. Perhaps there is no better example of how a research and development project led to a major building block in the design and execution of a nation’s war strategy. The individual who wishes to pursue additional reading on the Manhattan Project could start with the book Now It Can Be Told, by Leslie R. Groves (New York: Harper, 1962).

4. A military initiative, or project, that was a major turning point for the United States during World War II was the battle of Midway in June 1942. In the initial phase of this battle, three squadrons of U.S. torpedo bombers attacked the Japanese aircraft carriers Agai, Kago, Soryo, and Hiryu, in an attempt to draw first blood. A total of 41 U.S. torpedo planes left the carriers Enterprise, Yorktown, and Hornet. Traditional strategy called for such planes to have a fighter escort to protect them from air attacks as they made their torpedo runs. The U.S. planes attacked in three successive waves—from the start they were doomed. Japanese fighters and antiaircraft batteries on the Japanese fleet destroyed every plane in the first wave, and the next two waves were almost completely destroyed, with a loss of over 80 percent of the pilots. Only a few torpedoes were launched and none hit their targets. A tragic failure?

Historians have noted that the attack by the U.S. torpedo planes was ineffective by itself. But in the larger context of the battle of Midway, the Japanese fleet maneuvered to avoid the torpedo attack and was unable to sail into the wind to launch their planes against the U.S. fleet. When the U.S. SDB-3 Dauntless dive-bombers came in at 15,000 feet, there were no Japanese fighter planes to stop them. The Japanese carriers had heavily armed aircraft on their decks. During the next several minutes, the Japanese fleet suffered a decisive blow to its carriers from which it never recovered—and the naval war in the Pacific shifted in favor of the United States.8

Thus, what was a tragic failure in a part of the overall strategy for the Midway “project” actually provided an opportunity, or window, for the project to be successful, as the final project results contributed to the evolving Allied military strategy in the South Pacific.

2.7 OTHER EXAMPLES

Indicated below are a few examples of other projects that have provided the project “owner” or “sponsor” with an enhanced capability:

• Theatrical production involves the use of project teams, in part to evaluate the significant risks inherent in any theatrical production. Such productions involve a high financial investment with limited forecasting of probable success, use of highly skilled and expensive personnel, and great dependence on the producer’s professional experiences. Improvisation while production itself is still in progress is a particular challenge. One author has examined the use of project management techniques in the performing arts and has concluded that the use of such techniques could help improve the planning, cost control, and schedule control of such productions.9

• The H. J. Heinz Company has used alternative project teams in the management of that enterprise. An old factory in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, was shut down and a new one was designed and built at the same time—resulting in not a day of lost production. A massive investment in training was initiated to enhance the skills of its seasoned workforce. The company provided workers with an array of training tools—evaluation of basic skills, educational counseling, literacy education, classroom instruction, and training on the factory floor. The process of shutting the old factory down and starting up the new one provided the opportunity to bring about an unprecedented degree of employee involvement in day-to-day management. Teams of workers were provided the opportunity to solve problems and take on responsibility. Team-based quality and safety efforts slashed workers’ compensation costs by 60 percent and helped make Heinz the quality leader of the pet food industry. In England, at Heinz’s Harlesden and Kitt Green factories, worker-led project process evaluation teams helped streamline factory operations and improve quality, in some cases reducing overhead by as much as 40 percent. The teams developed their own plans, presented them to coworkers, and worked to implement the changes with scarcely any direct intervention by management.10

• When the Chrysler Corporation sets out to create a new automobile, it forms a project team of about 700 people from the different principal disciplines of the company to work on the project. A corporate vice president acts as a “godfather” to the team, but the team and its leaders plan and direct the work. After a suitable contract has been worked out with management, the team is turned loose to design and develop the product. There are no committees, no hierarchy outside of the team. By using these concurrent engineering teams, the time to design and develop a new vehicle model has been reduced nearly 50 percent.11

2.8 EARLY LITERATURE

In Chap. 1, some early literature on project management was mentioned. A summary of one of the more important articles of the literature is indicated later.

One of the first comprehensive articles that caught the attention of the project management community was published by Paul O. Gaddis in the Harvard Business Review (May-June 1959). This article, titled “The Project Manager,” describes the role of that individual in an advanced technology industry, the prerequisites for performing the project management job, and the type of training recommended to prepare an individual to manage projects. Several basic notions put forth by Gaddis contributed to a conceptual framework for the management of projects that holds true today. These basic notions were:

• A project is an organizational unit dedicated to delivering a development project on time, within budget, and within predetermined technical performance specifications.

• The project team consists of specialists representing the disciplines needed to bring the project to a successful conclusion.

• Projects are organized by tasks that require integration across the traditional functional structure of the organization.

• The project manager manages a high proportion of professionals organized on a team basis.

• The superior/subordinate relationship is modified, resulting in a unique set of authority, responsibility, and accountability relationships.

• The project is finite in duration.

• A clear delineation of authority and responsibility is essential.

• The project manager is a person of action, a person of thought, and a front person.

• Project planning is vital to project success.

• The project manager is the person between management and the technologist.

• The subject of communication deserves a great deal of attention in project management.

• Project teams will begin to break up when the members sense the project has started to end.

• The integrative function of the project manager should be emphasized.

• Status reporting is appropriate and valuable to management of the project.

• The role played by project management in the years ahead will be challenging, exciting, and crucial.

Project management, as an important and growing philosophy of management, came into its present conceptual framework as a culmination of experimentation with a variety of organizational liaison devices. In a sense, project management is the formalization of organizational liaison devices.

2.9 ORGANIZATIONAL LIAISON DEVICES

Project management evolved from a series of liaison devices that have been developed in contemporary organizations. These liaison devices, both formal and informal, have encouraged experimentation in integrating activities across organizational structures. Jay R. Galbraith is one of several researchers who have studied these liaison devices.12 His research provides in part the basis for a description of the following types:

• Individual liaison

• Standing committees

• Product managers

• Managerial liaison

• Project engineer

• Liaison position

Figure 2.5 depicts the interrelationships of these liaison devices in the context of the emergence of project management. A brief discussion of these types follows.

FIGURE 2.5 Organizational liaison activities.

Individual Liaison

The simplest and perhaps best form of liaison is that brought about by people who sense the need to work together and go about maintaining contact with others in the organization who have a vested interest in an activity under way. This liaison is usually self-motivated.

Standing Committees

Standing committees are used extensively to integrate organizational activities. These committees are found at all levels in the organization. At the top level such committees are called plural executives. They bring about synergy in the making and execution of key operational and strategic decisions for the organization.

Product Managers

Product managers usually are appointed to act as a focal point for the marketing and sales promotion of a product. Originating in the personal products area, the first product manager appeared before 1930. Persons occupying these positions usually were provided a small administrative staff and might have had profit/loss responsibility. They usually were not backed up by a specific team but rather worked closely in a coordinating role with other key individuals.

Managerial Liaison

When a more formal linkage is needed, a manager or supervisor is appointed who is in charge of several people through setting direction for the organizational unit and providing supervisory jurisdiction over the people. This form is widely used in modern organizations. As the organization increases in size and the work becomes more complex, additional managers are added, resulting in the creation of a chain of command eventually leading to large management structures. Other liaison roles as described in this chapter deal with the organizational complexity and bureaucracy to encourage contacts between individuals and organizational units.

Task Forces

Task forces often are used to bring a focus to organizational activities, usually those that are short-term. Members are appointed to the task force to work on an ad hoc problem or opportunity. During the time they are on the task force, members have a reporting relationship with their regular organizational unit and with the task force chairperson as well. When the purpose for which the task force was created is accomplished, the task force is dissolved.

Project Engineer

Sometimes a liaison position evolves through practice. Such is the case of the project engineer, who is responsible for directing and integrating the technical aspects of the design/development process. These positions have evolved in contemporary organizations to the point where the project engineer manages a product through all its engineering steps, from initial design to manufacture or construction.

Liaison Position

When a significant amount of contact is required to coordinate the activities of two or more organizational entities, a liaison position is formally established to bring about synergy and communication between the units. Usually this position has no direct formal authority over the organizational units but is expected to communicate, coordinate, pull together, and informally integrate work among the organizational units. Examples of liaison roles are an engineering or construction liaison person and a production coordinator who mediates between the production control, product engineering, and manufacturing. A purchase engineer who sits between purchasing and engineering is another example.

Other liaison positions may join line and staff groups. In the military establishment, the position of military aide-de-camp, a military officer acting as a secretary and confidential assistant to the superior officer of general or flag rank, is a liaison role. Originating in the French army, this position originally served as a camp assistant. The aide-de-camp carried out a coordinating and liaison role for his or her commanding officer; because the aide was close to the senior officer, there was a good deal of implied authority attached to the aide’s role.

Modern teams are used for a variety of purposes.

2.10 TEAMS

In modern organizations, project teams are used to complement an existing organizational design. An overriding feature of the team design is a departure from the traditional form of management in favor of a team form in which there are multiple authority, responsibility, and accountability relationships, resulting in shared decisions, results, and rewards. These teams not only include some of the teams already mentioned—project teams, project engineering teams, and task forces—but also production teams, quality circles, product design teams, and crisis management teams. The importance of the use of teams in contemporary organizations cannot be underestimated. Peters and Austin found that small-scale team organization and decentralized units are vital components of top performance.13

Some examples of project teams follow:

• At one end of a large IBM plant in Charlotte, North Carolina, 40 workers toil at building 12 products at once—hand-held bar-code scanners, portable medical computers, fiber-optic connectors for mainframes, satellite communications devices for truck drivers—a typical half day’s output on a line designed to make simultaneously as many as 27 different products. Each worker has a computer screen hooked into the factory network. Called a digital factory for its dependence on information technology, it is sometimes called soft manufacturing, in which software and computer networks have emerged along with people, which will set the tone for years, perhaps decades, in manufacturing. Soft manufacturing blurs the boundaries of the traditional factory by integrating production closer to suppliers and customers. Often an order is complete within 80 minutes, and depending on where the customer lives, he or she can have the product the same day or the day after. Workers on the factory floor are organized into teams that manage themselves and have real decision-making power. Teams of knowledge workers are the force that makes the digital factory go—teams of people are tied together along with equipment through the medium of information.14

• US Airways and American West are in the final development of strategy for the implementation of their merger. The two airlines have established project teams to persuade a diverse set of stakeholders—from a bankruptcy judge to shareholders, creditors, and regulators—that such a merger should be accomplished to form the nation’s largest full-service, low-cost airline. Extensive planning has been underway for months, with 14 project teams tackling everything from organizational structure and revenue management to vendor contracts, labor relations, and the management of human resources. Senior managers from both companies meet every Friday in person or on the phone for 2 or 3 hours to weigh in on the teams’ recommendations on hundreds of separate issues.

• In the past, the composition of the board of directors and employee seniority, along with labor contracts have been contentious. Seniority integration has been a major sticking point, leading to litigation and years of bad feelings. In this merger situation, US Airways workers are so senior compared with American West employees.15

• FedEx is a successful company in developing and pioneering overnight mail delivery services. Since the company started its delivery services, it has been at the leading edge of change. They have pioneered packaging and systems, technologies, and trade routes. The company’s services have given people access to the goods, information, and markets that make their growing expectations possible. Projects have been key to the growth and continued success of the enterprise.

• At FedEx, the strategy starts with a clear vision executed through the conceptualization and execution of projects. Over 20 years ago, the company envisioned China as a nexus of global supply and demand, and became the first all-cargo cargo carrier to that market in 1984. In FY05, FedEx Express launched the express industry’s first direct flight from land China to Europe.

• In 2005, a project was launched of Print FedEx Kinko’s software enhancement to the Microsoft Office Suite that turns the “print” function into a direct link to any U.S. FedEx Kinko’s Office and Print Center.

• The company has designed and is executing a project to build atop their hub at Oakland International Airport to provide approximately 80 percent of the peak-load energy demand. Other projects of rollout of energy-saving vehicles and more fuel-efficient aircraft joining their fleet of carriers evidence that FedEx is taking a much broader view of environmental needs for today and for the future.16

• At the Pennsylvania Electric Company’s Generation Division (Penelec), project management is used as a “way of life.” A centralized division planning group has been set up to link the different functional units required for a project and to integrate these units into a single project control system. Project teams are responsible for satisfying project objectives in the areas of life extension, maintenance, plant improvement, and the environment. On one project created to study turbine outage, the company estimated that the computerized project management system saved the company $300,000. Project management is recognized by senior division management as having credit to successfully allocate organizational resources to satisfy company objectives.17

• At Johnson Controls Automotive Systems Group, product development activities are done by using a company-institutionalized project management system. Use of project management by the company has prompted an increase in the training of employees and the creation of a standard approach for project management. The use of a common approach in project management has facilitated the development of organizational strategies, policies, procedures, and other ways of working on projects. Employees are educated in the company’s project management process; the improvement of the culture for project management—and the development of a common approach for the management of projects—has enabled the company to complete project development efforts in a timely and efficient manner.18

• At MBI, Inc., a company that produces collectibles, such as porcelain birds and plates, program (project) managers are used, one for each series of collectibles. Two key objectives guide these program managers: Get new customers at the lowest possible cost and retain them for follow-on purchases. The company “piggybacks” on the Franklin Mint’s product development costs and market research. Accordingly, industry observers believe that MBI, Inc.’s costs are much lower than its competitors’.19

• A central blood bank in a major U.S. city sees project management as a key management strategy in its world-class center for general support of the area hospitals’ blood banks. Today over 400 staff members collect and test the units of over 152,000 donations, distributing more than 400,000 blood products per year for 22 member hospitals. In addition, the bank provides pretransfusion testing services to three hospitals, reference testing to all areas involving clotting and bleeding disorders, and outpatient transfusion services for patients not requiring hospitalization.

• Nicolas G. Hayek and his colleagues at the Swiss Corporation for Microelectronics and Watchmaking have brought about one of the most spectacular industrial comebacks in the world—the revitalization of the Swiss watch industry. According to Hayek, “We are big believers in project teams.” He describes the use of project teams in the context of finding your best people, letting them take on a problem, disbanding them, and then moving on to the next problem. According to Hayek, the whole process of using projects works only if the whole management team focuses on developing products and improving operations—not fighting with each other.20

• Project management is used in the U.S. Justice Department. In the early 1980s the Reagan administration came close to merging the Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) and the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI)—a merger that was evaluated through the use of a project team. In 1984, over 56 separate projects were under way to integrate various functions of the two agencies. Only 9 of the 56 projects were completed; the others dropped into a state of bureaucratic limbo. An area that was successfully merged was training. Now the DEA has received $11 million to build its own training center in Quantico, Virginia—an effort that used project management to design, construct, and start up this new facility.21

• A large electronics company uses product design teams in simultaneous engineering to ensure the right timing and integration required during product and process development. These teams provide a focus for bringing together the people on a product development activity to coordinate and integrate an effort to support the product and process synergy. A product design team might include design engineers, technical writers, customer support people, marketing representatives, regulator and legal experts, purchasing agents, human factors analysts, and representatives from manufacturing and quality. These team members, acting in concert, provide both a focus and the necessary cross-fertilization of information and strategies to reduce the time required to get the product developed, manufactured, and in the customer’s hands.

• A large agricultural and industrial equipment manufacturer that does material, manufacturing, and product-applied research at the business-unit level uses concurrent engineering to accelerate product and process development cycles. Product development research is usually not considered high-risk because it is primarily applied research. Few new product development efforts are carried out; rather, the research is aimed at incremental product and process improvements. Product improvement includes the enhancement of the product’s performance as well as cost reduction and improvement of product quality. The research follows product lines and is evolutionary.

Companies today, facing unprecedented global competition, are finding it advantageous to cooperate with partners around the world to share resources, risks, and rewards. These partnerships take the form of strategic alliances and are used for many purposes, such as sharing the design of products and processes, sharing manufacturing and marketing facilities, and sharing in the financial risk and rewards. Technology is changing so fast today that companies are finding it impossible to assemble the resources to keep ahead of the competition. Indeed, a form of “cooperative competition” is becoming the standard for success in the unforgiving global marketplace.

Once the opportunity for a strategic alliance has been established, a joint project team is often appointed to begin the analysis and work on the alliance. This project team establishes the rationale for the alliance, makes recommendations for the selection of the partner(s), and initiates the analysis required for the development of a suitable working agreement among the partners. Key matters considered by these teams include the mission, objectives, goals, and strategies for the alliance. The team develops the alliance performance standards and builds a recommended strategy for how the joint arrangement will be integrated and managed. A key responsibility of the joint project team is to prepare a strategy for and participate in the execution of the negotiations required to bring about a meeting of the minds on the partnership alliance.

Once the alliance is consummated, the project team that managed the alliance during its development can be disbanded. Then the alliance will start the process of becoming “institutionalized”—merged into the ongoing businesses of the partners. Something that did not previously exist has been created through the use of project management technologies. Sometimes the partners will continue the project team’s existence to oversee the alliance in its early period and until the alliance can be integrated into the ongoing operations of the partners.

Many projects are becoming global, in some cases coming forth out of strategic alliances that global partners have negotiated. IBM alone has joined hundreds of strategic alliances with various companies in the United States and abroad, reflecting the fact that alliances have become a part of strategic thinking.

The challenges in a strategic alliance lie in the comparative management of the business and in the personal relationships between managers from different organizational cultures. Perhaps the biggest stumbling block to making an alliance work is the lack of trust among the partners.22

Project teams can be used for a wide variety of projects:

• Design, engineering, and construction of civil engineering projects such as a highway, bridge, building, dam, or canal

• Design and production of a military project such as a submarine, fighter aircraft, tank, or military communications system

• Building of a nuclear power generating plant

• Research and development of a new machine tool

• Development of a new product or manufacturing process

• Reorganization of a corporation

• Landing an astronaut on the moon and returning her or him safely to earth

Project work in the engineering, architecture, construction, defense, and manufacturing environments is easy to recognize. A new plant, bridge, building, aircraft, or product is something tangible; however, the project model applies to many fields, even to our personal lives.

These projects are the leading edge of change, in both our professional and private lives. Change encourages—or may force—us to do something different, at some cost, and on some time or schedule basis. These changes often take the form of projects, such as:

• Writing a book or article

• Painting a picture

• Having a cocktail party and dinner

• Restoring an antique piece of furniture or an automobile

• Getting married or divorced

• Having children

• Adopting a child

• Designing and teaching a course

• Organizing and developing a sports team

• Building a house or modifying an existing house

Students are feeling the impact of project management. In May 1985, the National Academy of Engineering held a symposium on U.S. industrial competitiveness. The symposium brought together some of the nation’s leading industrial and academic technological leaders to discuss the industrial competitiveness challenge and how the National Academy of Engineering might formulate its programs to improve U.S. competitiveness. During the symposium’s discussion of engineering education, it was recommended that the education of engineers for a future technological age require that the students develop the skills of leadership “for projects and programs...as well as technical leadership in their respective discipline.”23

2.11 THE PROJECT MANAGEMENT PROFESSIONAL SOCIETIES

Emerging professional associations are dedicated to project management. The largest in number is the Project Management Institute with more than 230,000 members. In Europe, the International Project Management Association has more than 100,000 members and represents national project management associations throughout Europe and Asia. The Australian Institute for Project Management and the Japanese Project Management Forum have a few thousand members. There are a wealth of small professional societies that are either directly promoting project management principles, practices, and processes or have formed to exchange project management information within a particular segment of industry. It is estimated that there are perhaps more than a million individuals who could benefit from membership in a project management professional society.

Professional societies typically provide collectively through members what one member or organization cannot provide. Out of this concept, there have emerged over the past 20 years several project management bodies of knowledge—some compatible except for the cultural aspects of a particular region and others more comprehensive as the knowledge areas are defined.

These bodies of knowledge are used for certification of individuals as to their qualifications in the project management field. Two types of certifications have emerged over the past decade—certification based on a person’s knowledge of the profession and certification based on a person’s competency in the profession. Each certification has its merits and challenges.

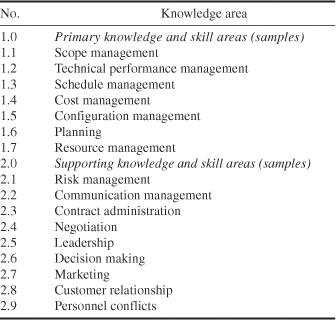

A sample of the areas of knowledge is given in Table 2.2. This table is not representative of any particular society, but given to promote thought on the full range of knowledge and skills that a project management practitioner might need to be successful.

TABLE 2.2 Sample Project Management Knowledge and Skill Areas

One of the distinguishing characteristics between different bodies of knowledge is the scope. Some bodies of knowledge are limited to the project’s life cycle, that is, that of a single project from start to finish, whereas others take a larger view and address the aspects of projects within an enterprise or even within a global context. Either body of knowledge is valid and the value of it is dependent upon the application.

The scope of the body of knowledge, of course, defines any certification program and whether it can be a “knowledge-based” or a “competency-based” certification. The number of areas included in the body of knowledge will show the range of knowledge needed to master the profession.

2.12 A PHILOSOPHY

A philosophy is a synthesis of all the knowledge, skills, and attitudes that one has about a field of learning and practice, the critique and analysis of fundamental beliefs about a discipline. A philosophy is also the system of motivating concepts and principles surrounding a field of study and practice. A field of thought or, to put it into more pragmatic terms, a “way of thinking” about a field of learning and practices, is what a philosophy is all about. Anyone who has been exposed to the field of management as either a manager or the objective of management has a philosophy or way of thinking about management. The study of the management discipline—and of project management in particular—enables one to broaden and sharpen the way one thinks about project management concepts and processes. Remember: To a large degree we participate on a project team, either as the team’s leader or as a member of team, based on the way we think about the project management discipline. Although we may not recognize it, the philosophy that we hold about project management influences the decisions we make and implement in the project management way of doing things.

2.13 BREAKING DOWN HIERARCHIES

Project management has caused many changes in how contemporary organizations operate. One major change deals with organizational hierarchies. Paramount companies today are tearing down traditional hierarchies. In today’s fast-changing, information-driven, and computer-facilitated competitive global economy, new paradigms on how to manage are coming forth. Some of the more important paradigms are described below:

• Project management and strategic management are highly interdependent.

• Work is organized around processes carried out by teams of employees working in an ever-changing organizational design.

• Temporary teams are drawn from a range of functional expertise and are formed around specific organizational projects.

• Few remaining vestiges of the traditional organization such as rigid hierarchy, command and control management styles, and bureaucratic policies and procedures remain.

• In the team-driven organization, the organizational design is more like a web of teams and projects rather than a clearly defined vertical hierarchy with clear discipline boundaries.

• Managers constantly move people from projects and teams that are phasing down and seek out promising teamwork and projects positioned for the future.

• E-mail, Internet, and other forms of electronic communication which enable people at all levels of the enterprise to keep abreast of what is happening are used.

• The work force is constantly trained and retrained.

• More cooperation with suppliers, customers, and even competitors should be developed.

• Egalitarian cultures should be fostered, but not to excess.

• A general sense of urgency and importance to speed up product, service, and process development is required.

Alternative teams that provide for broad cross-organizational cutting, such as new product development, new facilities, benchmarking, and reengineering initiatives have become the new organizational design, replacing narrowly focused departments and functions. By organizing the resources so that focus can be brought to the management of organizational processes—such as order fulfillment and new-product development—a synergy is possible that could not be realized through using the traditional organizational design based on functional specialization. Under functional specialization, each organizational unit became a fiefdom—a collection of talent and resources working in silos, usually independent of others, and developing and implementing strategies on its own.

The growth of project management is reflected to some degree by the recognition that was given to this discipline by contemporary literature. An excellent and timely article that appeared in Fortune magazine 10 years ago, doubtless, helped to accelerate the growth of project management. According to this article:

• Midlevel management positions are being cut.

• Project managers are a new class of managers to fill the niche formerly held by middle managers.

• Project management is the wave of the future.

• Project management is spreading out of its traditional uses.

• Managing projects is managing change.

• Expertise in project management is a source of power for middle managers.

• Job security is elusive in project management—because each project has a beginning and an end.

• Project leadership is what project managers do.24

Some of the unique characteristics of project management today include the following:

• Projects are ad hoc endeavors, which have a defined life cycle.

• Projects are building blocks in the design and execution of enterprise strategies.

• Projects are the leading edge of new and improved organizational products, services, and enterprise processes.

• Projects provide a philosophy and strategy for the management of change in the enterprise.

• The management of projects entails the crossing of functional and organizational boundaries.

• The management of a project requires that an interfunctional and interorganizational focal point be established in the enterprise.

• The traditional management functions of planning, organizing, motivation, directing, and control are carried out in the management of a project.

• Both leadership and managerial capabilities are required for the successful completion of a project.

• The principal outcomes of a project are the accomplishment of technical performance, cost, and schedule objectives.

• Projects are terminated upon successful completion of the cost, schedule, and technical performance objectives—or earlier in their life cycle when the project results no longer promise or have a strategic fit in the enterprise’s future.

• Project management is the major management philosophy for dealing with change.

2.14 TO SUMMARIZE

The major points that have been expressed in this chapter include:

• Strategic management and project management are interrelated in the management of an organization.

• The origins of project management are rooted in antiquity. The practice of project management has been carried out for centuries—if only in an unsophisticated manner, as compared to today’s practices. Nevertheless, the results of ancient project management are found in many places in the world. Project management is an idea whose time has come, in terms of the continued design and development of project-driven management strategies for industrial, military, educational, ecclesiastical, and social entities. Project management processes and techniques can be used for the management of personal resources such as getting married or divorced, building a house, having a cocktail party, or pursuing a hobby such as forming and managing a sports team.

• The basic considerations in any project center around the cost, schedule, and technical performance parameters—and how well the project results fit into the operational or strategic purposes of the enterprise.

• The results of project management usually take the form of a new or improved organizational product, service, and process.

• Many examples of the use of project management were provided in the chapter to include representation from many different organizations.

• A project tends to be ad hoc in nature, and the project results can be considered to be building blocks in the design and execution of operational and strategic initiatives for the enterprise.

• No one can claim to have invented project management—rather the concept and process evolved over a long period of time.

• The Project Management Institute (PMI®) is the leading professional association in the discipline. Other professional associations also exist whose purpose is to facilitate the spread of the theory and practice of project management.

• Sometimes projects fail to produce the results that were planned because of such factors as technology, economics, and political and social imperatives.

• Project management began to become conceptualized and documented in the 1950s in the sense of a philosophy and process for dealing with ad hoc opportunities.

• Prior to the emergence of project management, various organizational devices evolved to provide the means for an integration of activities across organizational structures.

• Project management has laid down the strategic pathway for the emergence of alternative teams in the modern organization to deal with such change initiatives as reengineering, benchmarking, simultaneous engineering, and self-managed production teams.

• In the early days of project management it was considered to be a “special case” of management. Today it has taken its rightful place in the theory and practice of management.

• When projects are managed, there tend to be a breakdown and an alteration of the traditional organizational hierarchies in favor of a horizontal form of organizational design.

• Project managers are emerging as a new class of managers to fill the niche, formerly held by middle managers.

• Projects provide a philosophy, strategy, and process for the management of change in the enterprise.

• The management of a project usually requires the crossing of functional boundaries of the enterprise.

• The traditional management functions of planning, organizing, motivation, direction, and control are carried out in dealing with a project.

2.15 ADDITIONAL SOURCES OF INFORMATION

The following additional sources of project management information may be used to complement this chapter’s topic material. This material complements and expands on various concepts, practices, and theory of project management as it relates to areas covered here.

• Curtis R. Cook, Just Enough Project Management (New York, NY: McGraw-Hill, 2005). This book translates a body of knowledge about project management meant for large, complex projects into a language that everyone involved with projects can understand. The book reduces its key message into a versatile four-step process to initiate, plan, control, and close projects. Tips, techniques, and war stories from the front line of contemporary projects gives the book a flair that reinforces its authoriative theme.

• Patrick Lencioni, The Five Dysfunctions of a Team (San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, 2002). A fine analysis of what makes teams work effectively. Every manager and professional will recognize themselves somewhere in the book. The author identifies and distills the typical problems that keep even the most talented teams from realizing their full potential. The book is an excellent guide on how to build and manage successful teams.

• Karen M. Bursic, “Self-Managed Production Teams”, in David I. Cleland (ed.), Field Guide to Project Management, 2nd ed., (John Wiley & Sons, 2004). Dr. Bursic analyzes the composition and effective operation of self-managed production teams. The chapter contains examples of such teams, along with suggested strategies for successful self-managed production teams. She closes with an expression of the future of teams to include the opinion that there will be an increased use of such in the organizational design and manufacturing organizations.

• Peter F. Drucker, “The Coming of the New Organization,” Harvard Business Review, January-February 1988, pp. 45–53. In this article, Peter F. Drucker opines that organizations of the future will be “information-based” and will have reduced numbers of hierarchical levels, with much of the work being done in task-focused teams. He further believes that these teams will work on new product and process development from the conceptual state of the product until it is established in the market.

• Francis M. Webster, Jr., PM 101, According to the Old Cunlludgeon, (Newton Square, PA19073: Project Management Institute, 2000). The author offers this book as a basic introduction to the fundamental concepts and processes of modern project management, and he delivers just that in this readable and enjoyable book. It is about the principles of modern project management, how many principles can be applied in modern organizations. Basic and sufficient information and explanations on how to manage projects are the themes of this book. It is designed to appeal to the professional who has been assigned in some capacity to the management of projects in the enterprise.

2.16 DISCUSSION QUESTIONS

1. How do projects fit into the overall design of enterprise purposes, in particular with the choice elements of an enterprise?

2. Describe and discuss situations in your work or personal experience that fit the definition of a project. How effectively were/are these managed?

3. In what ways do the concepts of project management appear to violate traditional, established ways of managing?

4. How do the three parameters of a project—cost, time, and technical performance—interact?

5. What are the various roles that need to be accounted for on a project team?

6. How do the leader’s and the project manager’s styles affect the way these roles are played?

7. List and discuss the various liaison devices described in the chapter.

8. What are some of the advantages of the use of teams in organizations?

9. Why is it important for project managers to adapt “synergistic thinking”?

10. Discuss the steps involved in the management of change. What additional steps can be taken?

11. How can a young professional’s experience in working on small projects benefit his or her professional development?

12. Describe what is meant by team management.

2.17 USER CHECKLIST

1. Are there clear and appropriate “choice elements” identified in your organization?

2. Does the management of your organization recognize projects and understand the concepts of project management?

3. How well does your organization use project management in dealing with change?

4. Are clear lines of authority, responsibility, and accountability defined for project team members?

5. How well are the liaison devices described in the chapter used to integrate activities across organizational lines?

6. Are cost, time, and technical performance objectives defined for each project? Are they properly managed? Do existing projects have a probable and suitable operation or strategic fit?

7. Does your organization use teams to its advantage? In what ways?

8. Is your organization prepared for change? Is change being managed effectively?

9. Are young professionals being properly trained in the concepts of project management so that they are prepared to take on the responsibilities of a project or team manager?

10. Does top management provide support and opportunities for functional and project managers to plan, organize, motivate, direct, and control those project activities for which they are responsible?

11. Does the organization use contemporaneous, state-of-the-art project management techniques in the management of projects?

12. How is project management integrated into the strategic management philosophies of the organization?

2.18 PRINCIPLES OF PROJECT MANAGEMENT

1. Project management has earned its rightful place in the evolution of the management discipline.

2. Strategic management and project management are interdependent in the management of an enterprise.

3. Projects are a key “choice element” in the management of an organization.

4. Projects are the building blocks of change in organizations.

5. The evolution of project management has influenced the continued evolution of general management theory and practice.

2.19 PROJECT MANAGEMENT SITUATION—EXTERNAL AND INTERNAL PROJECTS

Projects, as building blocks in the design and execution of enterprise strategies, can be either external or internal in nature. An external project is one undertaken for, or on behalf of, stakeholders who are not part of the enterprise structure, such as design and construction of a bridge, highway, or new product design. In an external project, the customer is located outside the enterprise, such as another company, government, or military organization. An internal project is one to be carried out primarily for the improvement of organizational processes, such as productivity improvements, training initiatives, organizational restructuring, or reengineering. Internal projects usually have an internal customer, such as a manufacturing manager who wishes to update the company’s manufacturing equipment, build a new plant, or develop enhanced information systems capability.

Companies that are in economic difficulties often undergo downsizing or restructuring. Improvements in organizational processes can be gained from reengineering projects. The development of new award systems, flexible work practices, improvement of quality, or the flow of work on the production line, can be accomplished by using project teams. Although many of these projects are modest, compared to large projects that are being developed for an outside customer, for the members of the enterprise the internal projects usually indicate that a change in the operating policies is forthcoming.

Organizations are basically systems of people using resources to accomplish enterprise mission and purposes. Changing how an organization works is thus fundamentally about changing how people work and relate to each other. Organizational development projects are meant to be a planned process of change for the people in an organization’s culture, often using management principles and behavioral processes. A major reason why some of these changes fail is because the action that is planned and undertaken is not treated as a project and—not managed as a project.

2.20 STUDENT/READER ASSIGNMENT

The reader/student should select an organization with which he or she is familiar and accomplish the following:

1. Identify the internal and external projects that are underway in the organization.

2. Determine the strategic or operational changes that each of the projects will likely impact.

3. Assess the effectiveness with which each project is being managed. Are there differences in how such projects are being managed?

4. Identify some probable forthcoming changes likely to impact the organization for which project management concepts and process can be applied.

5. Give thought to what project management principles might be applied in the management of these projects.