CHAPTER 3

THE PROJECT MANAGEMENT PROCESS

“The distance is nothing; it is only the first step which counts.”

MADAME DUDEFFARD, 1697–1784

3.1 INTRODUCTION

Project management is a series of activities embodied in a process of getting things done on a project by working with project team members and other stakeholders to attain project schedule, cost, and technical performance objectives. The project management process is adapted from the general management process.

In this chapter the project management process will be explained along with an exploration of the project life cycle. How to manage this life cycle will be examined, along with an explanation of how project life cycles and uncertainty are linked. An early linkage of a project life cycle and a product life cycle will be presented.

Project management is a series of activities embodied in a process of getting things done on a project by working with members of the project team and with other people in order to reach the project schedule, cost, and technical performance objectives. This description helps identify project management, but it does not tell too much about how a project manager reaches project goals and objectives. This chapter will describe the project management process along with the idea of the life cycle. First we describe the management process.

3.2 THE GENERAL MANAGEMENT PROCESS

A process is defined as a system of operations in the design, development, and production of something, such as a project. Inherent in such a process is a series of actions, changes, or operations that bring about an end result, in the case of a project attainment of its cost, schedule, and technical performance objectives. Another meaning of a process is that it is a course or passage of time in which something is created—an ongoing movement or progression.

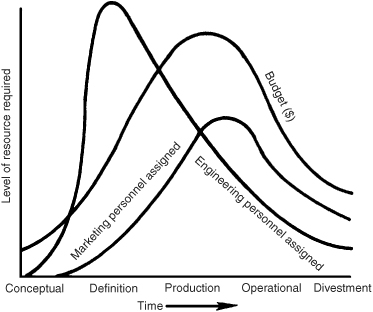

As a manner and means of progressing, a project management process sets the tone for the conceptualization of project management; the planning and execution of concepts, methods, and policies; and the commitment of resources to the project endeavors. Taken in its entirety, a project management process provides a paradigm for how the management functions of planning, organizing, motivation, directing, and control will be carried out in the commitment of resources on the project.

Figure 3.1 provides a simple model of the management functions portrayed in the larger context of the management process. Each of these functions can stand alone—yet in their design and execution they are interdependent in the overall management process of an organization or a project.

FIGURE 3.1 The management process.

The management discipline is usually described as a process consisting of distinct yet overlapping major activities or functions. A brief review of the early conceptualization of the management discipline in terms of the major activities or functions involved follows.

The management discipline that received recognition early in the twentieth century reflected to some degree the practices of the time. Although there were a few singular writings in historical times, there was no attempt to organize and portray an overall philosophy and concept of management. But in the early writings of Frederick W. Taylor and Henri Fayol, the first integrated ideas about management started to take form. Taylor’s book, The Principles of Scientific Management (1911), centered around the improvement of capabilities of people on the production line. Fayol, on the other hand, wrote his classic General and Industrial Management from the perspective of the overall management of the enterprise. Fayol’s definition of management as consisting of forecasting and planning, to organize, to command, and to coordinate and to control, set the stage for the differentiation of managerial activities from the technical activities of the enterprise. To quote Fayol: “To plan is to foresee and provide a means of examining the future and drawing up the plan of action. To organize means building up the dual structure, material and human, of the undertaking. To command means maintaining activity among the personnel. To coordinate means binding together, unifying, and harmonizing all activity and effort. To control means seeing that everything occurs in conformity with established rules and expressed command.”1 Fayol goes on to note that management is an activity spread between the head and members of the body corporate. His early description of managerial functions being carried out from the highest to the lowest levels of an enterprise established the traditional hierarchical state of management—a state of perception and thought which characterized both the theory and practice of management for many decades. Any perception of the horizontal nature of management was largely confined to the idea of coordinating the technical activities of the enterprise. In the traditional paradigm of management authority, responsibility and accountability were primarily considered to be vertical forces, extending from the senior level of the enterprise down to the worker level.

The idea of using teams as an alternative organizational design was described very little in the literature, but there were singular examples where the use of teams to integrate functional activities in the enterprise was recommended. An early advocate of teams was Mary Parker Follett.

In the 1920s she extolled the benefits of teams and participative management, and said that leadership comes from ability rather than hierarchy. She advocated empowerment and tapping the knowledge of workers, and supported the notion of cross-functioning, in which a horizontal rather than a vertical authority would foster a freer exchange of knowledge within the organization. She fervently believed that knowledge and experience determine who should lead.2

A simple yet important way of further describing the management process through its major functions is indicated below:

• Planning What are we aiming for and why? In the execution of this function, the organization’s mission, objectives, goals, and strategies are determined.

• Organizing What’s involved and why? In carrying out the organizing function, a determination is made of the need for human and nonhuman resources—and how those resources will be aligned and used to accomplish the organization’s mission. Authority, responsibility, and accountability are the “glue” that holds an organization together.

• Motivating What brings out the best performance of people in supporting the organization’s purposes?

• Directing Who decides what and when? In the discharge of this management function, the manager provides the face-to-face leadership of the organizational members.

• Controlling Who judges results and by what standards? In this function the manager monitors, evaluates, and controls the effectiveness and efficiency in the utilization of organizational resources.

Figure 3.2 portrays the relationship of project management resources and the core functions of project management. There is much literature describing these management functions. Thousands of articles and hundreds of books are published every year about the management discipline.

FIGURE 3.2 The core functions of project management.

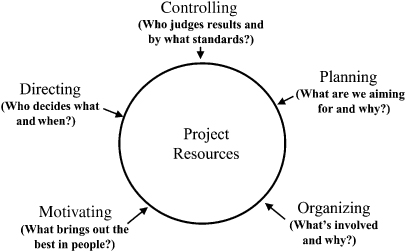

Table 3.1 shows the principal responsibilities between project management and general management. Both draw on the theory and practice reflected in the management discipline. There are some subtle differences, however, reflected in the main management considerations that are involved in the management of the project or the enterprise, as the case may be. Both general management and project management have the same basic philosophies, even though the application of the management process may differ depending on the applications in each area. Both make and implement decisions, allocate resources, manage organizational interfaces, and provide leadership to the people who are involved in the enterprise and the project. The differences and similarities are subtle yet important for both the managers and the professionals who are involved.

TABLE 3.1 Principal Responsibilities: Project Management and General Management

3.3 THE PROJECT MANAGEMENT PROCESS

In Table 3.2, the project management process is portrayed in terms of its major functions. The activities noted under each of these functions are only representative. Effective project management requires many more activities or “work packages” under each of these functions. More descriptions of these functions are found elsewhere in this book.

TABLE 3.2 Representative Functions/Processes of Project Management

Planning: What are we aiming for and why?

Develop project objectives, goals, and strategies.

Develop project work breakdown structure.

Develop precedence diagrams to establish logical relationship of project activities and milestones.

Develop time-based schedule for the project, based on the precedence diagram.

Plan for the resource support of the project.

Organizing: What’s involved and why?

Establish organizational design for the project team.

Identify and assign project roles to members of the project team.

Define project management policies, procedures, and techniques.

Prepare project management charter and other delegation instruments.

Establish standards for the authority, responsibility, and accountability of the project team.

Motivating: What motivates people to do their best work?

Define project team member needs.

Assess factors that motivate people to do their best work.

Provide appropriate counseling and mentoring as required.

Conduct initial study of impact of motivation on productivity.

Directing: Who decides what and when?

Establish “limits” of authority for decision making for the allocation of project resources.

Develop leadership style.

Enhance interpersonal skills.

Prepare plan for increasing participative management techniques in managing the project team.

Develop consensus decision-making techniques for the project team.

Controlling: Who judges results and by what standards?

Establish cost, schedule, and technical performance standards for the project.

Prepare plans for the means to evaluate project progress.

Establish a project management information system for the project.

Evaluate project progress.

The functions used in management of a project are the principal elements in making and implementing decisions about the use of resources applied to project purposes. A checklist to review how well these functions are carried out can be useful. A representative general checklist is shown in Table 3.3.

TABLE 3.3 Decisions of the Team Management Functions

Team planning

What is the mission or “business” of the team?

What are the team’s principal objectives?

What team goals must be attained in order to reach team objectives?

What is the strategy used by the team to accomplish its purposes?

What resources are available for the team’s use in accomplishing its mission?

Team organization

What is the basic organizational design of the team?

What are the individual and collective roles of the team that must be identified, defined, and negotiated?

Will the team members understand and accept the authority, responsibility, and accountability that is assigned to them as individuals and as a team?

Do the team members understand their authority and responsibility to make decisions?

How can the team effort be coordinated so that the members will work in harmony, not against one another?

Team motivation

What motivates the team to do their best work?

Does the team manager provide a leadership style acceptable to the members of the team?

Is the team “productive”? If not, why not?

What can be done to increase the satisfaction and productivity of the team members?

Are the team meetings conducted in such a manner that people attending them are encouraged? Discouraged?

Team direction

Is the team leader qualified to lead the team?

Is the team leader’s style acceptable to the members of the team?

Do individual members of a team assume leadership in the areas where they are expected to lead?

Is there anything that the team leader can do to increase the satisfaction of the team members?

Does the team leader inspire confidence, trust, loyalty, and commitment among the team members?

Team control

Have performance standards been established for the team? For the individual members? What feedback on the team’s performance does the manager have who appointed the team?

How often does the team get together to formally review its progress?

Has the team attained its objectives and goals in an effective and efficient manner?

Do the team members understand the nature of control in the operation of the team?

Source: Adapted from M. H. Mescon, et al., Management (New York: Harper & Row, 1991), p. 167.

3.4 THE PROJECT LIFE CYCLE

Project management is a continuing process. New demands are always put on the project team and have to be coordinated by the project manager through a process of planning, organizing, motivating, directing, and controlling. As new needs come up before the project, someone has to satisfy these needs, solve the problems, and exploit the opportunities. The project originates as an idea in someone’s mind, takes a conceptual form, and eventually has enough substance so that key decision makers in the organization select the project as a means of executing elements of strategy in the organization. In practice, the project manager must learn to deal with a wide range of problems and opportunities, each in a different stage of evolution and each having different relationships with the evolving project. This continuing flow of problems and opportunities, in a continuous life-cycle mode, underscores the need to comprehend a project management process which, if effectively and efficiently planned for and executed, results in the creation of project results that complement the organizational strategy.

Managing a large project is so complex that it is difficult to comprehend all the actions that have to be taken to successfully plan and execute the project. We need to divide the project into parts in order to grasp the full significance of each part and just where that part fits in the scheme of the project. We have to look at the project parts, its “work packages,” its logical flow of activities, and the phases that the project goes through in its evolution, growth, and decline.

Managing a project is like the management of any activity. Two fundamental steps are involved in such management, namely, the making and implementation of decisions. There is a substantial body of knowledge regarding how decisions can be made—in particular how to consider the evaluation of risk and uncertainty in the potential use of resources committed through the decision process. Decision analysis in projects is an important responsibility of the project team, facilitated by the project manager.

Using a model of the project’s life cycle is useful in identifying and understanding the total breadth and longevity of the project and as a means to identify the management functions involved in the project life cycle. A project’s life cycle contains a series of major steps in the process of conceptualizing, designing, developing, and putting in operation the project’s technical performance “deliverables.” These major steps are the key work elements around which the project is managed. The context of a project life cycle—and how the conceptualization and development of that life cycle provide a useful model for project management—will be described in the material that follows.

But first, an example of a project’s life cycle. All projects go through a series of phases in their life cycle as they progress to completion, transforming the project resources to a product, service, or organizational process. As the project results are transformed into a product, service, or organizational process, they create value for the enterprise. Modifications and improvements are typically added to the project results as they are provided to customers in the marketplace by way of new models, modified configuration, reduced price, and so forth, and as the results of the projects compete in the marketplace for which they were designed and developed. Project results, like most other things in the world, are always undergoing change in order to remain competitive in their marketplaces. A new car, or a car that has been modified from the original configuration, may eventually be discontinued because of a key decision made by the car manufacturer. For example, in December 2000 the General Motors Company announced their intention to kill the 103-year-old Oldsmobile name, cut 15,000 jobs, and reduce 15 percent of GM’s factory capacity in Europe. These were the first steps in a sweeping overhaul of the biggest U.S. automaker since the dark days of the early 1990s. GM is also setting up special project teams to work with suppliers on how to save money for parts and supplies. GM management hopes that the elimination of the Oldsmobile car and cost savings with suppliers will provide funds for the development of “hot new cars and trucks” that the number 1 automaker is counting on to reverse the decades of declining market share.3

The reader can note the many opportunities in the GM situation presented earlier for the use of project management:

• Development of the original Oldsmobile auto—although not recognized as such because a formal project management discipline did not exist at that time. What did exist was the need to bring together many disciplines and organizational functions to develop the original car and all subsequent models.

• Canceling the Oldsmobile auto required the use of project management, as well as using the discipline in downsizing the manufacturer’s plants and other facilities.

• Setting up project teams to work with suppliers to reduce vendor costs.

• Need for project teams to develop new “hot cars” and trucks to reverse GM’s declining market share.

Thus project management was used to create change in the strategic and operational purposes of the company, and to deal with the change coming from the marketplace that was impacting the company.

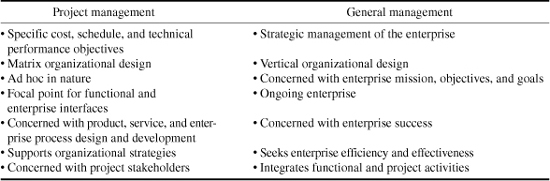

The phases of a project life cycle—and what happens to the project during its life cycle—depend on the distinctive nature of the project. The phases that are described in this chapter are generic and representative. Figure 3.3 is intended to provide a broad notion of the life cycle of a generic project to show how the project starts off with a conceptual model, goes through definition of its cost, schedule, and technical performance objectives, becomes operational, and will finally go into a divestment phase and is likely to be replaced by a new or improved project. Many different yet similar phases have been described in the life of a project. These phases typically include:

FIGURE 3.3 Generic model of project life cycle.

• Idea The generation of the notion or concept for a new product, service, or process that provides the basis for the creation of something new for the enterprise, which did not previously exist.

• Research The patient, systematic search and inquiry and examination into a field of knowledge. Such an inquiry is taken to establish facts or principles, and when successful, should convert an idea into a practical plan for further work. If the applied research does not result in anything of value, the project will be redirected or terminated as appropriate.

• Design The means for the conversion of the idea into a plan for a product, service, or organizational process.

• Development Usually means taking a design specification and converting it into an actual product, service, or process. This is done through added features of appearance and configuration change, and through the stages of experimental models, breadboard models, experimental prototypes, and production prototypes. The resulting outcome of the development phase is a product or service ready for production.

• Marketing Involves determining the need for the product or service, and the development of a sales and marketing plan to deliver the results to customers. The marketing effort is usually under way prior to or during the design and development efforts.

• Production The conversion of human and nonhuman resources into a product or service that provides value to the customers.

• After-sales services Means to provide the customer with maintenance, technical documentation, and logistics support for the product or service during the time that the product or service is being used by customers.

Projects, like organizations, are always in motion as each proceeds along its life cycle. Projects go through a life cycle to completion, hopefully on time, within budget, and satisfying the technical performance objective. When completed, the project joins an inventory of capability provided by the organization that owns the project.

All projects—be they weapons systems, transportation systems, or new products—begin as a gleam in the eye of someone and undergo many different phases of development before being deployed, made operational, or marketed. For instance, the U.S. Department of Defense (DOD) uses a life-cycle concept in the management of the development of weapons systems and other defense systems. This life cycle identifies a number of phases, each with specific content and management approaches. Between the various phases are decision points, at which an explicit decision is made concerning whether the next phase should be undertaken, its timing, and so on. Generically, these phases are as follows:

1. Concept refinement phase—During this phase the technical, military, and economic baselines are established and the management approach is established.

2. Technical development phase—During this phase the technical feasibility of the system’s technology is proven and validated, which may include prototyping and testing of components.

3. System development and demonstration phase—During this phase complete test systems are constructed and capability demonstrations conducted.

4. Production and deployment phase—During this phase a limited number of systems are built and deployed into operational organizations to provide an initial operating capability.

5. Operations phase—During this phase enough systems are built and deployed to operational units to provide a full operational capability. Maintenance issues and selected improvements are developed and deployed throughout the useful life of the system.

The management of technology can be viewed in a life-cycle context. Cleland and Bursic have, in a research project, studied the management of technology within a major corporation. One of their conclusions is that technology can be managed from the context of a life cycle. Figure 3.4 illustrates this life cycle.

FIGURE 3.4 The life cycle of technology. (Source: David I. Cleland and Karen M. Bursic, Strategic Technology Management: Systems for Products and Processes, AMACOM American Management Association, 1992, p. 23.)

The results of this research project set a new standard in the corporation for the use of project management as a focus for the development of this new product.4

3.5 MANAGING THE LIFE CYCLE

One of the first undertakings in planning for a project is to develop a rough first estimate of the major tasks or work packages to be done in each phase.

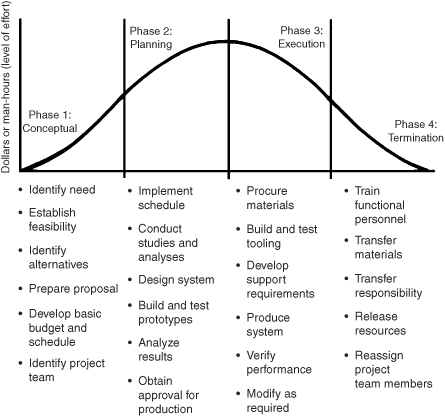

There are many ways of looking at a project life cycle. Adams and Brandt suggest two ways of looking at the managerial actions by project phase and the tasks accomplished by project phase. See Table 3.4 and Fig. 3.5.

TABLE 3.4 Managerial Actions by Project Phase

FIGURE 3.5 Tasks accomplished by project phase. [Source: John R. Adams and Stephen E. Brandt, “Behavioral Implications of the Project Life Cycle,” in David I. Cleland and William R. King (eds.), Project Management Handbook (New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold, 1983), p. 227.]

Once established, the life-cycle model should be updated as more is learned about the project. As the project progresses through its life cycle, the project exhibits ever-changing levels of cost, time, and performance. The project manager must make correspondingly dynamic responses by changing the mix of resources assigned to the project as a whole and to its various work packages. Thus, budgets will fluctuate substantially in total and in terms of the allocation to the various project work packages. The need for resources and various kinds of expertise will similarly fluctuate, as will virtually everything else. This is portrayed in Fig. 3.6, which shows changing levels of budget and of engineering and marketing personnel for various stages of the life cycle.

FIGURE 3.6 Changing resource requirements over the life cycle. [Source: John R. Adams and Stephen E. Brandt, “Behavioral Implications of the Project Life Cycle,” in David I. Cleland and William R. King (eds.), Project Management Handbook (New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold, 1983), p. 227.]

This constantly changing picture of the life cycle is an underlying structural rationale for project management. The traditional hierarchical organization is not fully designed to cope with managing such an always-changing mix of resources. Rather, it is designed to control and monitor a much more static entity that, day to day, involves stable levels of expenditures, numbers of persons, and so forth.

As has been stated earlier, project management is used by many different organizations. Banks, such as the Security Pacific National Bank in Los Angeles, California, use project management. At this bank, project management was used in the automation of its loan collection system. Security Pacific had decided to centralize all its collections, scattered throughout some 600 offices and collection centers. The plan was to devise six regional adjustment centers and a charge card center for all collection operations. Using project management, the development project was completed on time and within the budget that was allocated for it. There was a 100 percent increase in collector productivity in the first 6 months of operations under the new collection system. There was also a 95 percent decrease in paperwork generated by the collectors. Also, there was a significant reduction in loan delinquency and charge-offs. It was estimated that Security Pacific would save about $4 million by the end of the year because of the implementation of the new collection system.5

3.6 PROJECT LIFE CYCLES AND UNCERTAINTY

As the project life cycle progresses, the cost, time, and performance parameters must be “managed.” This involves continuous replanning of the as yet undone phases in the light of emerging data on what has actually been accomplished.

The project team must rethink much during the project life cycle to modify and fine-tune the work packages for each phase. Archibald notes, “The area of uncertainty is reduced with each succeeding phase until the actual point of completion is reached.”6

Many organizations can be characterized at any time by a “stream of projects” that place demands on its resources. The combined effect of all the projects facing an organization at any given time determines the overall product, service, and process status of the organization at that time and gives insight into the organization’s future.

The projects facing a given organization at a given time typically are diverse—some products are in various stages of their life cycles and embody different technologies; other products are in various stages of development. Management subsystems are undergoing development. Organizational units are in transition. Major decision problems, such as merger and plant location decisions, are usually studied as projects.

Moreover, at any given time, each of these projects usually will be in a different phase of its life cycle. For instance, one product may be in the conceptual phase undergoing feasibility study; another may be in the definition phase. Some might be in production. Others are being phased out in favor of upcoming models.

The challenges associated with the overall management of an organization that is involved in a stream of projects are influenced by life cycles, just as are the challenges associated with managing individual projects. In project-driven organizations whose main business is management of the stream of projects passing through the organization, the mix of projects in their various phases is most challenging, particularly in allocating workforce, funding resources, scheduling workloads, and so on, to maintain a stable organizational effort.

In Chap. 1, the probable length of the life cycle for building the historical artifacts was noted. Some contemporary projects have a long life cycle as well. At Motorola, the Iridium 11-year project resulted in the launching of a 250-ton rocket carrying the first 3 of 66 planned satellites into orbit, 420 nautical miles above the earth. By the time the entire constellation of satellites was up in September 1998, Motorola and its 16 coinvestors expected to spend close to $5 billion, making the project one of the largest privately funded infrastructure projects ever. The technical, regulatory, and political complexity of the project is numbing. More than 25,000 complex design elements have come forth. The project team scoured the globe, seeking partners and money to build the project, which began a new era of humanity-helping global interconnectedness. At the end of 1996, 2000 people were working on the project, up from 20 at the start. Marketing of the Iridium project was challenging. A sophisticated global marketing campaign is under way to sell its phones—aiming at vastly different markets around the world. Even if the project has less than hoped for success, it has yielded valuable indirect benefits, such as enhanced technology, greater attention to satellite technology, and a modern production facility that can be used for other satellite systems.7

Drug research projects take an average of 12 years and cost an average of about $359 million. During the life cycle of these projects, the disciplines critical to the project change. Projects often start with a biologist, and then a chemist and other disciplines become involved. Once developed, the new drugs have to be tested on animals and finally on human beings; then, on to manufacturing. Development projects require enormous amounts of expertise with a willingness to promote the free flow of information across disciplines and organizational boundaries.

The point to be remembered is that the management process has direct application to the management of the project resources and should so be approached in a life-cycle context.

3.7 TO SUMMARIZE

The major points that have been covered in this chapter include:

• The project management process was described as a guide for the management of those major activities involved in having an idea for a project and carrying that idea through to attainment of the project objectives.

• A process was described as a system of operations in the design, development, and production of something—such as a project.

• Henri Fayol, the noted French author, was the first individual to conceptualize and define the management functions. His definition set the stage for the subsequent examination of these functions in the management of an enterprise.

• Planning deals with how to determine the likely future forces facing an enterprise and how to prepare the enterprise for its future.

• Organizing deals with how best to provide an orderly alignment of the people and the resources used by the enterprise for the accomplishment of its purposes.

• Motivation establishes the philosophy, attitude, and means for bringing out the best in people.

• Directing is the face-to-face situation, in which the leader provides a vision and the means of accomplishing that vision for the project.

• Monitoring, evaluation, and control provide the means for determining how well the project and organizational strategies are being used in meeting objectives and goals through the employment of predetermined strategy.

• A checklist to assist the project manager in determining how effectively decisions are being made on the project was provided in the chapter.

• Everything living in the world today goes through a life cycle. Projects are no different.

• Several paradigms of a project life cycle were provided to assist the reader in understanding how such paradigms can guide the management of a project.

• A project life cycle can be portrayed using the work packages of the project appropriately placed in the phases in that life cycle.

• Some projects have a long life cycle, such as that presumed about the building of the Great Pyramids. However, contemporary projects can have a long life cycle as well.

• Any new or improved product, service, or process goes through a life cycle as conceptual models are built, and design, development, production, and after-sales support initiatives are carried out in such a manner that the project results provide value to the customer.

• The management system for a project is built around the design and execution of the managerial functions that have been described in this chapter.

3.8 ADDITIONAL SOURCES OF INFORMATION

The following additional sources of project management information may be used to complement this chapter’s topic material. This material complements and expands on various concepts, practices, and the theory of project management as it relates to areas covered here.

• John R. Adams and Miguel E. Caldentey, “A Project Management Model,” and J. Davidson Frame, “Tools to Achieve On-Time Performance,” Chaps. 6 and 9 in David I. Cleland (ed.), Field Guide to Project Management, 2nd ed. (John Wiley & Sons, Hoboken, NJ, 2004).

• Harold Koontz and Cyril O’Donnell, Principles of Management, 2nd ed. (New York: McGraw-Hill Book Company, 1959). This book is considered to be one of the early “classics” in presenting a management theory that embodies a principle and a process perspective. The authors believe that management is one of the more important activities through its task of getting things done through people.

• Charles B. Randall, The Folklore of Management (New York: Wiley, 1997). The first edition of this book was written more than 30 years ago. A basic commonsense treatment of business management, Randall reveals the elements of success as well as failure in the corporate world. The simplicity and humor of this book, plus its insight into the management discipline, makes it a “management classic” in the literature. Any manager, whether at the senior or junior level of the enterprise—or a project manager—will find excellent insight into the management challenge in modern times by reading this book.

• Thomas C. Belanger and Jim Highsmith, “Another Look at Life Cycles,” in David I. Cleland (eds.), Field Guide to Project Management, 2nd ed. (Hoboken, NJ; John Wiley & Son, 2004). The authors revisit project life cycles for software development with examples of standard processes and models for the reader. Examples of life cycles are illustrated and described to promote understanding and comprehension.

• William R. Duncan, “The Process of Project Management,” Project Management Journal, vol. 24, no. 3, September 1, 1993. In this article the process of project management is integrative, principally because a change in one department usually affects other departments. Trade-offs among project objectives are often required; successful project management can only be realized through the optimum handling of such interactions.

3.9 DISCUSSION QUESTIONS

1. Identify and define the management functions discussed in the chapter.

2. Within the management function of planning, project managers and team members should settle on project objectives, goals, and strategies. How can this task help define the “strategic fit” of the project to the organization?

3. Discuss the difference between organizational policies and procedures.

4. Project review meetings are often used as a tool for controlling projects. In general, what kinds of questions should be addressed in these meetings?

5. List and briefly define the phases of a generic project life cycle.

6. What management functions are most important in the conceptual phase of a project life cycle?

7. During the definition phase of a project, it is important for management to design and develop a management system to support the project. Discuss the importance of each system.

8. Discuss what is meant by the project “losing its identity” and being “assimilated into the ongoing business of the user.”

9. Discuss the importance of the divestment phase as a tool for avoiding technological obsolescence.

10. What is meant by the phased approach for project development?

11. How can a project manager, by understanding the project life cycle, use the concepts of this chapter to help direct and control projects?

12. Discuss the challenge of managing a project-driven organization with ongoing projects at various stages in their life cycles.

3.10 USER CHECKLIST

1. Do the managers of your organization understand and use the management functions in the management of projects?

2. Do the managers of your organization understand the project management process?

3. In the early stages of projects within your organization, are objectives, goals, and strategies clearly defined?

4. Are project management roles assigned? Are standards for responsibility and accountability established?

5. Does management consider the needs of individual team members in order to motivate people to do their best work?

6. How well does your organization use participative management techniques and consensus decision making in your project management work?

7. What techniques do project managers, within your organization, use to control project problems?

8. Do your organization’s managers truly understand the implications of the project life cycle?

9. Does your organization use a systematic approach for managing projects?

10. During the conceptual phase of a project, does the organization attempt to determine the potential strategic fit of the project?

11. Does the organization recognize the need for a management system for managing projects?

12. Are projects purposely put through the divestment phase in order to avoid technical obsolescence? Why, or why not?

3.11 PRINCIPLES OF PROJECT MANAGEMENT

1. Project management is a series of activities comprising the process of applying management principles to project activities.

2. The management process consists of the organic functions of management.

3. All projects go through a series of phases in their life cycle as they progress to completion, transforming the project resources to a product, service, or organizational process to support organizational strategies.

4. The area of uncertainty in a project is reduced with each succeeding phase until the actual point of completion is reached.

5. A project life cycle can be portrayed using the work packages of the project appropriately placed in the phases of that life cycle.

3.12 PROJECT MANAGEMENT SITUATION—STRATEGIC MONITORING AND CONTROL

In Chap. 2, the interdependent relationship between strategic management and project management was presented. In Chap. 3, the project management process has been described within the organic functions of management: planning, organizing, motivating, directing, and controlling. In the material that follows, the control function is presented from the perspective of strategic management.

Strategic Management Monitoring, Evaluation, and Control

Strategic management, like any other management activity, needs to be continually monitored, evaluated, and controlled to ascertain how the actual results compared with the results that were planned.

Steps in the Control Cycle

There are several distinct steps in the project-oriented strategic management control system. In the material that follows, a brief insight into the nature of these steps is provided. We will consider performance standards first.

Performance Standards

Performance standards are based on the “choice elements” that have been established during the strategic process for the enterprise. Of these choice elements, projects and goals are particularly important. Goals represent milestones in the progress of the enterprise in accomplishing its objectives. Many of the goals of the enterprise are made up of projects under development and completion. For example, a goal for the enterprise to improve its manufacturing operations would have several key projects such as:

• Acquisition of state-of-the-art machine tools

• Construction of a new “green field” manufacturing facility

• Design and implementation of new training programs

• Design and development of automated factory production capabilities

• Redesign of the organizational structure to facilitate the operation of “self-managed” production teams

• Benchmark manufacturing capabilities of “best in the industry” firms as well as enterprise competitors

Following good project management practices, each of these projects would have appropriate objectives, schedules, and cost estimates. By reviewing the status of these projects, valuable insight into the progress that is being made toward the realization of company goals would be gained.

Comparing Planned and Actual Performance

An explicit review of the actual progress vis-à-vis planned progress provides strategic managers the intelligence to make an informed judgment of how well the strategic goals of the enterprise are being developed and implemented through the use of projects. An explicit review helps give answers to the following key questions:

• Is the project’s progress consistent with the elements needed to support the strategic purposes of the enterprise?

• If there are deviations from the planned progress, how significant are these deviations?

• Will any changes be required in the resources directed to the project to more fully support the strategic purposes of the enterprise?

• Will the project’s progress, or lack thereof, adversely impact the chances of the choice elements being adequately executed in the enterprise?

Corrective Action

Corrective action on the projects can take many forms of reprogramming, reallocation of assets, cancellation of the project, or reformulation of the goals of the enterprise, which the project was destined to support. Corrective actions directed to a particular project may have the result of impacting other projects—or even other goals of the enterprise.

An effective policy and process for reviewing the progress being made on those projects that support enterprise choice elements will enable the senior managers to tune their use of resources in preparing the entity for its future as if that future mattered.

Strategic management should be carried out at every level in the enterprise. Accordingly, the choice elements described in Chap. 2 have applications at each level; of course, the time dimension surrounding these choice elements is different. As these choice elements are developed and are used for each level in the enterprise, opportunities exist for the coordination and assessment of how well the overall enterprise accomplishes its strategic purposes.

As a result of the use of a strategic control system, certain initiatives of the enterprise will be changed. A few examples of such changes are listed in Table 3.5.

TABLE 3.5 Examples of Changes Coming Out of a Strategic Control System

Changes in choice elements

Development of new/modified products, services, processes

Changes in market strategy

Modification of R&D programs

Cancellation of enterprise projects

Downsizing

Restructuring of organizational design

Changes in resource requirements

3.13 STUDENT/READER ASSIGNMENT

The reader should do a “self-test” by seeking the answers to the following questions—as well as following the instructions indicated for a fuller appreciation of the processes involved in tracking, monitoring, and controlling the design and execution of strategic management done in the context of projects.

1. Why does it make sense to review the status of the projects in an enterprise when evaluating the performance of strategic management within the enterprise?

2. Select an organization with which the reader is familiar and identify the “stream of projects” in that organization that should be reviewed to ascertain how well the organization is being prepared for its future.

3. What does a “failing” project in an enterprise do to the development and execution of future strategies for the organization? Identify some “failing” projects in an organization with which you are familiar. Relate these “failures” to difficulties on the organization’s part in the design and execution of future changes expected in the organization’s environments.

4. Based on your current understanding of project management, what alternative strategies might be available to use in managing change in the enterprise?

5. What information should the project team have to make a strategic management control system operable?