CHAPTER 5

THE STRATEGIC CONTEXT OF PROJECTS1

“Many of us are like the little boy we met trudging along a country road with a cat-rifle over his shoulder. ‘What are you hunting, buddy?’ we asked. ‘Dunno, sir, I ain’t seen it yet.’”

R. LEE SHARPE

5.1 INTRODUCTION

An emerging conviction among those professionals who do research on, publish, and practice project management is the belief that projects are building blocks in the design and execution of organizational strategies. An ongoing and competitive organization has a “stream of projects” flowing through the organization that support changes in operational and strategic initiatives.

In this chapter, the strategic relationship of projects to organizational purposes will be considered. A project selection framework will be suggested. An initial look at project planning will be provided, along with a description of the project “owner’s” need for participating in the selection and use of projects to support organizational purposes. A key part of this chapter includes the description of a project management system, which provides a philosophy and standard for a “systems view” in the management of projects.

5.2 STRATEGIC TRANSITIONS

The most dangerous time for an organization is when old strategies are discarded and new ones are developed to respond to competitive opportunities. The changes that are appearing in the global marketplace have no precedence; survival in today’s unforgiving global marketplace requires extraordinary changes in organizational products, services, and the organizational processes needed to identify, conceptualize, develop, produce, and market something of value to the customers. Projects, as building blocks in the design and execution of organizational strategies, provide the means for bringing about realizable changes in products and processes. Senior managers, who have the residual responsibility for the strategic management of the enterprise, can gain valuable insights into both the trajectory of the enterprise and the speed with which the competitive position of the enterprise is being maintained and enhanced. This can be done by conducting a regular review of the status of the “portfolio of projects” in the enterprise.

A belief that projects are building blocks in the design and execution of future strategies for the enterprise means that the organizational planners recognize that preparing for the future on the basis of extrapolations of the past results from a well-understood and predictable platform of past experience is not valuable—and can be dangerous to the health of the enterprise. Although planning based on extrapolation of the past has some value for an ongoing business providing routine products and services, it makes little sense when the enterprise’s future is dependent on developing and producing new products and services through revised or new organizational processes. All too often people persist in believing that what has gone on in the past will go on into the future—even while the ground is shifting under their feet. If the enterprise is engaged in a business where competition is characterized by the appearance of unknown, uncertain, or not yet obvious new products and services, especially to the competition, then project-driven strategic planning is needed. Project-based strategic planning assumes that:

• Little may be known of the new product or service but much is assumed about potential customer interest in the forthcoming initiative.

• Decision making on the project during its early conceptual phases is based on what information is available. Assumptions concerning the potential future business success of the innovation are an important source of knowledge on which decisions can be made.

• Assumptions concerning the new venture are systematically converted into meaningful databases as new knowledge concerning the innovation evolves through study by the project team.

• Even after the prototype is developed and field-tested with customers, uncertainty remains as to how well the product or service will do in the competitive marketplace.

Kerr-McGee is an energy and chemical company with assets of more than $14 billion. The company is involved in two worldwide businesses: oil and gas exploration and production and the marketing of titanium dioxide pigment. A statement of the continued implementation of strategy in 2004 consisted in part of the following projects:

• More than 9000 identified exploration projects resulting from the Westport and prior HS Resources acquisitions

• Executed major development projects within budget and on or ahead of schedule

Kerr-McGee has also joined five other companies in a project to develop multiple ultra deep-water natural gas discoveries in the eastern Gulf of Mexico, where they operate the Merganser field and hold interests in two other anchor fields involved in the projects, Vortex and San Jacinto. The company attributes their success in the management of projects through commitment and in the use of innovative advanced technology and outstanding teamwork.2

5.3 IMPLICATIONS OF TECHNOLOGY

Management of an enterprise so that its future is ensured requires that the technology involved in products and/or services and organizational processes is approached from two principal directions: the strategic or long-term perspective and the systems viewpoint. In both directions, projects play a key role. In this chapter, these two directions will be woven into a project management philosophy, in which projects are building blocks in the design and execution of organizational strategies. A couple of examples of how contemporary organizations deal with projects make the point:

Product development in the automotive industry is a complex process. Several years ago it took about 60 months to bring a vehicle to production. Today, it can be done in less than 24 months. Within the General Motors (GM) company, the product design process has been revamped, in part through the establishment of a program management office responsible for the facilitation and tracking of product development projects. The program management function includes the responsibility to forecast required resources and ensure that work tasks (work packages) are accomplished on time and on budget. Rigorous program management has meant a cultural change for GM. The new program management–oriented culture encourages people to request help when needed, and others are willing to provide that help, wherever located in the company. Program managers serve as watch dogs on programs and can raise a red flag when problems arise that will require the use of program management tools. The overall characteristics of the new GM program management process includes:

• An alignment of organizational resources.

• The creation of a single unified program management organization.

• Provide a single voice for program (project) management in the company.

• Coordinate major work package policies and processes.

• Improve market competitiveness.3

In the early 1990s, Boeing invested heavily in new technology so that it could design a commercial aircraft, the 777 twin jet, entirely by computer. It connected 1200 engineers and countless other staffers to 2200 workstations and four mainframes, in Seattle, Philadelphia, the Midwest, and Japan. That technology enabled the aircraft manufacturer to solve virtually every design problem through computer animation—without having to build a prototype—and thereby limit the cost of making design changes down the line. For instance, when a team of engineers discovered a glitch in the jet’s wiring, they “fixed” it instantly on their 3-D digital model. The technology cut the design time for the 777 to half.4

Projects are essential to the survival and growth of organizations. Failure in project management in an enterprise can keep the organization from accomplishing its mission. The greater the use of projects in accomplishing organizational purposes, the more dependent the organization is on the effective and efficient management of those projects. Projects are a direct means of creating value for the customer in terms of future products and services. The pathway to change will be through projects. Future strategies will entail a portfolio of projects, some of which will survive and lead to new products and/or services and the manufacturing and marketing processes that will beat out the competition. With projects playing such a pivotal role in future strategies, senior managers must approve and maintain surveillance over these projects to determine which ones can make a contribution to the strategic survival of the company. Two authors state:

The challenge facing senior management seeking to implement revolutionary change within the organization is to manage that change outside the straitjacket of the existing bureaucracy, procedures, and norms. Projects and project management help senior management to do precisely that.5

The Ford Motor Co. has a project underway to overhaul its $90 billion-a-year global outsourcing strategy by offering larger, long-term contracts to a smaller group of suppliers on future models, a switch that could save billions of dollars a year. The company will cut by more than half the number of suppliers from whom it buys key parts. This effort by Ford promises a shake-up in the beleaguered auto-parts industry, a key part of the U.S. manufacturing base. In the past several months, several auto suppliers have field for chapter 11 bankruptcy protection amid broader pressure on the industry from the rising price of fuel, steel, and other commodities. Ford’s move to revamp its outsourcing strategy is the latest project to turn around the nation’s No. 2 automaker, whose automotive business reported a $1.1 billion operating loss in the second quarter and whose debt recently was downgraded to junk-bond status. GM rolled out a new global outsourcing strategy earlier this month, telling suppliers they will have to match prices for products manufactured and shipped from low-wage countries.6

As rivals imitate each other’s operational competitive strategies, the more probable it is that their strategies will converge. Competition becomes a series of behaviors that look similar—and no one competitor can become a big winner. Competition based on operational performance becomes self-defeating, leading to wars of competitive attrition. Unfortunately, many of the “flavors of the year” in the last 10 years have led to diminishing competitive returns. Competition based on continuous improvement reinforced by many of the flavors of reengineering, benchmarking, change management, and so forth, have drawn all too many enterprises into a “me too” mentality that has inhibited true creativity and innovation in creating strategic pathways for true competition in strategic performance.

The responsibility for allowing companies to degenerate into competition based on operational improvements clearly rests with the company’s leaders. Unfortunately, this means that such leaders have failed to recognize their larger role beyond just operational stewardship, namely, a proactive role in selecting and executing the use of resources to provide a competitive, strategic pathway for the enterprise. Enterprise leaders have to work with the creative and innovative talent in the enterprise’s pool of people and define and communicate new directions, allocating resources, making trade-offs through the study of alternatives, and making the hard choices of what to do for the future and—just as important—what not to do by way of committing organizational resources.

A product or process development project is a business venture—the creation of something that does not currently exist but which can provide support to the overall organizational strategy being developed to meet competition. Many projects are found in successful organizations.

5.4 A STREAM OF PROJECTS

An enterprise that is successful has a “stream of projects” flowing through it at all times. When that stream of projects dries up, the organization has reached a stable condition in its competitive environment. In the face of the inevitable change facing the organization, the basis for the firm’s decline in its products, services, and processes is laid—and the firm will hobble on but ultimately fail.

In the healthy firm, a variety of different preliminary ideas are fermenting. As these ideas are evaluated, some will fall by the wayside for many reasons: lack of suitable organizational resources, unacceptable development costs, a position too far behind the competition, lack of “strategic fit” with the enterprise’s direction, and so on. There is a high mortality rate in these preliminary ideas. Only a small percentage will survive and will be given additional resources for study and evaluation in later stages of their life cycles. Senior managers need to ensure that evaluation techniques are made available and their use known to the people who provide these preliminary innovative ideas. Essentially this means that everyone in the organization needs to know the general basis on which product and process ideas can survive and can be given additional resources for further study. Senior management must create a balance between providing a cultural ambience in the enterprise that encourages people to bring forth innovative product and process ideas and an environment that ensures that rigorous strategic assessment will be done on these emerging ideas to determine their likely strategic fit in the enterprise’s future.

A large retailer’s strategy in assessing strategic opportunities is to jump-start a number of small projects at a relatively low cost and then shift the money into the promising ideas as the development work evolves. One example of such a promising project involves the development of electronic shelf tags, which would display pertinent information about a product, including the unit price, price per ounce, sales data, or whatever the company wanted to highlight. No longer would the employees have to change the traditional shelf tags. Another project is under development for a ceiling-mounted scanner to track the number of customers entering and exiting a store, thus alerting personnel that additional sales assistance is needed in specific departments. Another project borrows from just-in-time manufacturing inventory management concepts and processes. Products are shipped to distribution centers only when needed, thus reducing inventory requirements. Suppliers under this new procedure would write their own purchase orders by looking into the retailer’s inventory databases and would ship products in time to keep the shelves from becoming bare.

When the use of project management is described in an enterprise, it is easy to think of just one project in the organization. Often we think of a large single dedicated project team led by a project manager who has the proper authority and responsibility needed to do the job. What usually exists after the enterprise has experimented with project management for a while is that many projects are under way, each having its own life-cycle phases. Team members may be working on several different small projects. As the use of project management continues to expand, the matrix organizational design emerges more fully and many projects share common resources provided by the functional entities and appropriate stakeholders. As the growth of project management continues and different projects come and go, there are some unique forces at work. The projects share common resources but will likely have objectives that are not shared with other projects, particularly if a diverse set of customers is involved. As projects start and are closed out or terminated for cause, a new mix in the use of resources comes forth. New projects may have a higher priority than the existing ones. As the competition for resources gets under way in the matrix organization, the opportunities for conflict in the assignment of the resources to the projects will erupt, often requiring senior management to intervene in deciding how the project priorities will impact the priorities for the use of the resources; the opportunity for gamesmanship emerges. Also, having many projects under way provides the opportunities for politics to enter the picture.

5.5 STRATEGIC RELATIONSHIP OF PROJECTS

Organizational conceptual planning forms the basis for developing a project’s scope in supporting the organizational mission. For example, a project plan for facilities design and construction would be a series of engineering documents from which detailed design, estimating, scheduling, cost control, and effective project management will flow. Conceptual planning, while forming the framework of a successful project, is strategic in nature and forms the basis for the following:

• Contributing, through the execution of strategies, to the organizational goals, objectives, and mission

• Standards by which the project can be managed

• Coping with the market and other environmental factors likely to have an impact on the project and the organization

Senior management deficiencies in the organization using project management will probably be echoed in the management of the projects. For example, an audit conducted in the early 1980s of a gas and electric utility that experienced problems with a major capital project found several key deficiencies in that utility, such as:

• Weak basic management processes

• No implementation of the project management concept for major facilities

• Fragmented and overlapping organizational functions

• No focus of authority and accountability7

5.6 DETERMINING STRATEGIC FIT

Projects are essential to the survival and growth of organizations. Failure in the management of projects in an organization will impair the ability of the organization to accomplish its mission in an effective and efficient manner. Projects are a direct means of creating value for customers—both customers in the marketplace and “in-house” customers, who work together in creating value for the ultimate customer in the marketplace. The pathway to change is through the use of projects that support organizational strategies. Future strategies for organizations entail a portfolio of projects, some of which survive during their emerging life cycle and create value for customers. Because projects play such a pivotal role in the future strategies of organizations, all managers need to become actively involved in the efficiency and effectiveness with which the stream of projects is managed in the organization. Surveillance over these projects must be maintained by managers to provide insight into the probable promise or threat that the projects hold for future competition. In considering these projects, managers need to find answers to the following questions:

• Will there be a “customer” for the product or process coming out of the project work?

• Will the project results survive in a contest with the competition?

• Will the project results support a recognized need in the design and execution of organizational strategies?

• Can the organization handle the risk and uncertainty likely to be associated with the project?

• What is the probability of the project’s being completed on time, within budget, and at the same time satisfying its technical performance objectives?

• Will the project results provide value to a customer?

• Will the project ultimately provide a satisfactory return on investment to the organization?

• Finally, the bottom line question: Will the project results have a strategic fit in the design and execution of future products, organizational processes and services?

As managers conduct a review of the projects under way in organizations, the above questions can serve to guide the review process. As such questions are asked and the appropriate answers are given during the review process, an important message will be sent throughout the organization: Projects are important in the design and execution of our organizational strategies!

The question of the strategic fit of a project is a key judgment challenge for executives. Who should make such decisions? Clearly those executives whose organizational products and services will be changed by the successful project outcome should be involved. Senior executives of the enterprise should act as a team in the evaluation of the stream of projects that should flow through the top of the enterprise for assessment and determination of future value. Participative decision making concerning the strategic fit of projects is highly desirable. For some executives this can be difficult, particularly if they have been the entrepreneurs who conceptualized the company and put it together. Such founding entrepreneurs tend to dominate the strategic decision making of the organization, reflecting their ability in having created the enterprise through their strategic vision in developing a sense of future needs of products, organizational changes, and services.

The Cameco Company is involved in four business segments:

• Uranium

• Conversion services

• Nuclear electricity generation

• Gold

Cameco holds a vision to be a dominant nuclear energy company, producing uranium fuel and generating clean electricity. Their business is nuclear energy—a leading global supplier of uranium fuel and a growing supplier of clean electricity. The company’s values are:

• We value the contribution of every employee. We seek strong relationships based on honest communications with employees and their families, customers, shareholders, and suppliers.

• We pursue excellence in all undertakings and value people who strive to produce work of the highest quality. We encourage creativity, innovation, and continual improvement.

• We seek to earn the respect of all people with whom we interact. We inspire trust based on honest, fair, ethical behavior.

• Our operations provide a safe, humane, and physical environment. We are committed to practices that promote the health of employees and safeguard the environment in areas affected by the facilities we operate during and after their utilization.8

During the strategic fit review of organizational projects, insight should be gained into which projects are entitled to continue assignment of resources and which are not. Senior managers need to decide; the project manager is an unlikely person to execute the decision. Most project managers are preoccupied with bringing the project to a successful finish, and they cannot be expected to clearly see the project in an objective manner of supporting the enterprise mission. There is a natural tendency for the project manager to see the termination of the project as a failure in the management of the project. Projects are sometimes continued beyond their value to the strategic direction of the organization. The selection of projects to support corporate strategies is important in developing future direction.

But senior executives, too, can lose their sense of future vision for the enterprise. Or they can become fixated on favorite development projects that may not make any strategic sense to the organizational mission and goals. For example, in a large computer company, the founder’s dominance of key project decisions drove out people whose perceptions of a project’s strategic worth were contrary to that of the CEO. A new-products development group was abruptly disbanded by the CEO, who had sharp differences of opinion with the group executive over several key projects. This group executive had disagreed with the CEO on a key decision involving continuing development of a computer mainframe project whose financial promise was faint—if potentially attainable at all.

5.7 THE VISION

Projects and organizational strategies start with a vision. A “vision is the art of seeing things invisible to others,” according to Jonathan Swift.

5.8 PROJECTS AND ORGANIZATIONAL MANAGEMENT

Projects, goals, and objectives must fit together in a synergistic fashion in supporting the enterprise mission. Project success by itself may not contribute to enterprise success. Projects might, early in their life cycle, show promise of contributing to enterprise strategy. A project that continues to support that mission should be permitted to grow in its life cycle. If the project does not provide that support, then a strategic decision faces the senior managers: Can the project be reprogrammed, replanned, and redirected to maintain support of the enterprise mission, or should the project be abandoned?

Project managers cannot make such a strategic decision because they are likely to be preoccupied with bringing the project to a successful finish, and a project termination decision is not their responsibility. Such managers may lack an overall perspective of the project’s strategic support of the enterprise mission. Therefore, the decision of what to do about the project must remain with the general manager, who is the project “owner” and has residual responsibility and accountability for the project’s role in the enterprise mission and usually puts up the money for the project.

Project success is very dependent upon an appropriate synergy with the enterprise’s success. The management of the project and the management of the enterprise depend on a synergistic management approach—planning, organizing, evaluation, and control tied together through an appropriate project-enterprise leadership. This synergy is shown in Fig. 5.1.

FIGURE 5.1 Project/strategic enterprise synergy. (Source: David I. Cleland, “Measuring Success: The Owner’s Viewpoint,” Proceedings, Project Management Institute Seminar/Symposium, Montreal, Quebec, September 20–25, 1996, p. 6.)

Projects are designed, developed, and produced or constructed for a customer. This customer or project owner may be an internal customer, such as a business unit manager who pays for product development by the enterprise central laboratory. An external customer might be a utility that has contracted with an architectural and engineering firm to design, engineer, and build an electricity generating plant.

Senior managers, who have the responsibility to sense and set the vision for the enterprise, need a means of marshaling the resources of the organization to seek fulfillment of that vision. By having an energetic project management activity in the enterprise, an organizational design and a development strategy are available to assist senior managers in bringing about the changes and synergy to realize the organizational mission, objectives, and goals through a creative and innovative strategy. Leadership of a team of people who can bring the changes needed to the enterprise’s posture is essential to the attainment of the enterprise’s vision. As additional product and/or service and process projects are added to marshal the enterprise’s resources, the strategic direction of the enterprise can be guided to the attainment of the vision. When projects are accepted as the building blocks in the design and execution of organizational purposes, a key strategy has been set in motion to keep the enterprise competitive. Such strategies are dependent on the quality of the leadership in the enterprise.

5.9 PROJECT PLANNING

Why is project planning so important? The answer is simply because decisions made in the early phases of the project set the direction and force with which the project moves forward as well as the boundaries within which the work of the project team is carried out. As the project moves through its life cycle, the ability to influence the outcome of the project declines. After design of the project is complete early in the project life cycle, the product cost and product quality have been largely determined. Senior managers tend to pay less attention during the early phases of the project than when the product development effort approaches the prototype or market-testing stage. By waiting until later in the life cycle of the project, their influence is limited in the sense that much of the cost of the product has been determined. Design has been completed, and the manufacturing or construction cost has been set early in the project. Senior managers need to become involved as early as possible, and they must be able to intelligently assess the likely market outcome of the product, its development cost, its manufacturing economy, how well it will meet the customers’ quality expectations, and the probable strategic fit of the resulting product in the overall strategic management profile of the enterprise. In other words, when senior managers become involved early in the development cycle through regular and intelligent review, they can enjoy the benefits of leverage in the final outcome of the product and its likely acceptance in the marketplace. What happens early in the life cycle of the project essentially lays the basis for what is likely to happen in subsequent phases. Because a development project is taking an important step into the unknown—with the hope of creating something that did not previously exist—as much information as possible is needed to predict the possible and probable outcomes. For senior managers, to neglect the project early in its life cycle and leave the key decisions solely to the project team is the implicit assumption of a risk that is imprudent from the strategic management perspective of the enterprise. Project planning is discussed more fully in Chap. 13.

5.10 PROJECT MANAGEMENT SYSTEM

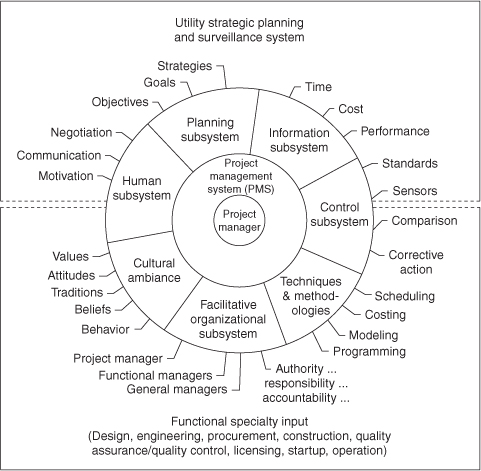

Once the mission of the enterprise is established through the operation of a strategic planning system, planning can be extended to select and develop organizational goals, objectives, and strategies. Projects are planned for and implemented through a project management system composed of the following subsystems.9

The facilitative organizational subsystem is the organizational arrangement that is used to superimpose the project teams on the functional structure. The resulting “matrix” organization portrays the formal authority and responsibility patterns and the personal reporting relationships, with the goal of providing an organizational focal point for starting and completing specific projects. Two complementary organizational units tend to emerge in such an organizational context: the project team and the functional units. The project control subsystem provides for the selection of performance standards for the project schedule, budget, and technical performance. The subsystem compares actual progress with planned progress, with the initiation of corrective action as required. The rationale for a control subsystem arises out of the need to monitor the various organizational units that are performing work on the project in order to deliver results on time and within budget.

The project management information subsystem contains the information essential to effective control of the projects. This subsystem may be informal in nature, consisting of periodic meetings with the project participants who report information on the status of their project work, or a formal information retrieval system that provides frequent printouts of what is going on. This subsystem provides the data to enable the project team members to make and implement decisions in the management of the project.

Techniques and methodology is not really a subsystem in the sense that the term is used here. This subsystem is merely a set of techniques and methodologies, such as PERT, CPM, and related scheduling techniques, as well as other management science techniques which can be used to evaluate the risk and uncertainty factors in making project decisions.

The cultural ambience subsystem is the subsystem in which project management is practiced in the organization. Much of the nature of the cultural ambience can be described in how the people—the social groups—feel about the way in which project management is being carried out in the organization. The emotional patterns of the social groups, their perceptions, attitudes, prejudices, assumptions, experiences, and values, all go to develop the organization’s cultural ambience. This ambience influences how people act and react, how they think and feel, and what they say in the organization, all of which ultimately determines what is taken for socially acceptable behavior in the organization.

The planning subsystem recognizes that project control starts with project planning, because the project plan provides the standards against which control procedures and mechanisms are measured. Project planning starts with the development of a work breakdown structure, which shows how the total project is broken down into its component parts. Project schedules and budgets are developed, technical performance goals are selected, and organizational authority and responsibility are established for members of the project team. Project planning also involves identifying the material resources needed to support the project during its life cycle.

The human subsystem involves just about everything associated with the human element. An understanding of the human subsystem requires some knowledge of sociology, psychology, anthropology, communications, semantics, decision theory, philosophy, leadership, and so on. Motivation is an important consideration in the management of the project team. Project management means working with people to accomplish project objectives and goals. Project managers must find ways of putting themselves into the human subsystem of the project so that the members of the project team trust and are loyal in supporting project purposes. The artful management style that project managers develop and encourage within the peer group in the project may very well determine the success or failure of the project. Leadership is the most important role played by the project manager.

Figure 5.2 depicts the project management system in the context of a public utility commission with all its subsystems. The utility owners responsible and accountable for the effective management of the project work through their boards of directors and senior management along with the project manager, functional managers, and functional specialists.

FIGURE 5.2 The project management system. (Source: Adapted from D. I. Cleland, “Defining a Project Management System,” Project Management Quarterly, vol. 110. no. 4, p. 39.)

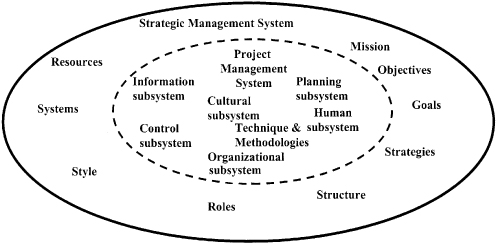

In Fig. 5.3, the integrated relationship of a strategic management system and project management system is portrayed. Indeed, the subsystems of a project management system touch all the “choice elements” of a strategic management system.

FIGURE 5.3 The integration of project management systems and strategic management systems.

5.11 TO SUMMARIZE

Some of the major points that have been expressed in this chapter include:

• The most dangerous time for an enterprise is when new strategies are being developed and old ones are being discarded.

• Projects are building blocks in the design and execution of organizational strategies.

• People have a tendency to believe that the future will be a simple extrapolation of the past.

• Projects are the leading edge of product, service, and organizational process change in the enterprise.

• Improvement of operations, such as through the use of a reengineering initiative, has its place. But the enterprise must have strategic projects under way to prepare the organization for its uncertain future.

• Examples were given in the chapter of how contemporary organizations have used projects to change their products, services, and organizational processes.

• A successful enterprise has a “stream of projects” flowing through it all the time. Conversely, an organization that is failing is likely to have few projects under way to allocate resources for future purposes.

• A series of important questions can be asked to determine if an existing or proposed project has a “strategic fit” in the enterprise.

• A simple scoring model was suggested as a useful way to select projects from an inventory of potential projects that exist in the enterprise.

• There is a synergy between projects and the other elements of the enterprise. This synergy is shown in Fig. 5.1.

• A brief introduction to project planning was given along with a promise of more material on project planning contained in Chap. 13.

• The project owner has specific responsibilities in the overall management of the project.

• A project management system is a useful way of depicting the principal subsystems that are involved in the management of a project. Unless all of these subsystems are up and running, there is likely to be a deterioration in the effectiveness and efficiency with which the project is managed.

5.12 ADDITIONAL SOURCES OF INFORMATION

The following additional sources of project management information may be used to complement this chapter’s topic material. This material complements and expands on various concepts, practices, and theory of project management as it relates to areas covered here.

• David I. Cleland. “Strategic Planning” and “New Ways to Use Project Teams,” Chaps. 1 and 33, in David I. Cleland (ed.), Field Guide to Project Management, 2nd ed. (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, 2004). These chapters describe the concept and process of strategic planning stated in terms relevant to the practitioner. The first chapter sets the stage for project management in the context of strategic planning in the organization. Chapter 33 describes some of the newer uses to which project teams are being put in contemporary organizations.

• David I. Cleland, Strategic Management of Teams (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 1996). This book is written from the point of view of a manager who envisions using teams as strategic initiatives in dealing with change. The author explains how to prepare the organization for the use of teams, how teams can sharpen the enterprise’s competitive edge, specific team functions, and the probable impact of teams on organization culture. Finally, the book summarizes the results that teams have achieved for organizations that have implemented them.

• John Stanley Baumgartner, Project Management (Homewood, Ill: Richard D. Irwin, 1963). This is probably the first book on project management that was published by a commercial publisher. The book’s principal focus is on the management process with which the project manager of DOD and NASA projects had to contend. It is intended primarily for people in companies doing business with the U.S. government. The author also suggests that it may also be of interest to construction and other project-oriented activities. The book’s value is in the background that is provided as project management began its emergence as a major building block in management thought and theory.

• Peter W. G. Morris, The Management of Projects (London: Thomas Telford, 1994). This book provides an interesting and comprehensive survey of the issues involved in appraising, beginning, and accomplishing any project. It details the experience and lessons learned from the management of projects over the past 50 years. The book concludes with a prediction of how the discipline of project management will likely develop over the next 10 to 20 years.

• Sergio Pellegrinelli and Cliff Bowman, “Implementing Strategy through Projects,” Long Range Planning, vol. 27, no. 4, 1994, pp. 125–132. The authors make the point that the challenge facing senior managers who wish to bring revolutionary change within an organization is to manage that change outside the “straitjacket” of the existing bureaucracy. Projects and project management can help senior management to do just that. They also make the important point that the concept of a project has to be understood in a wider sense as a vehicle for achieving change. The authors also state that most strategic initiatives can be conceived and handled as projects—and that the conceptualization and implementation of a strategy usually involves defining and undertaking a range of projects that address a component of the strategy.

5.13 DISCUSSION QUESTIONS

1. Discuss the importance of the strategic management of projects.

2. What is the alternative, if any, to strategic planning?

3. Why is it important for general managers to take responsibility and accountability for the strategic fit of a project?

4. Discuss criteria for when a project would or would not be a strategic fit.

5. Discuss how a project could be selected for an organization and not be a strategic fit.

6. Discuss the importance of owner participation in measuring and controlling the success of a project.

7. What hinders senior management involvement in large organizational projects?

8. What kinds of questions need to be addressed in order to measure project success?

9. What contemporaneous state-of-the-art management techniques can be used to help control and measure project success?

10. Discuss the responsibilities of project owners with respect to strategic planning and management.

11. Discuss the importance of establishing policies that describe the organizational structure and the authority, responsibility, and accountability of managers within the structure.

12. List and define the various subsystems of the project management system.

5.14 USER CHECKLIST

1. Are the projects within your organization being managed from a strategic perspective? Why or why not?

2. What quantitative and qualitative methods does your organization use for project selection?

3. Does the top management of your organization accept the responsibility for determining the strategic fit of projects?

4. Does the top management of your organization accept the responsibility for monitoring the cost, time, and technical performance objectives of major projects?

5. How do the senior managers of your organization monitor the ongoing progress of major projects?

6. What issues do you see regarding senior managers not monitoring project progress and what is the result?

7. Do the key project managers use state-of-the-art management techniques to control the projects of the organization?

8. Are organizational projects being managed from a project management system perspective?

9. Does the top management of your organization accept the responsibility to develop and implement adequate strategic plans for the enterprise and for projects?

10. Are adequate information systems available to support managers and professionals working on various organizational projects?

11. Does appropriate policy exist that defines the organizational structure and the fixing of authority, responsibility, and accountability of managers at each organizational level?

12. Does the top management of your organization foster an attitude that supports the management of projects?

5.15 PRINCIPLES OF PROJECT MANAGEMENT

1. Projects are building blocks in the design and execution of organizational strategies.

2. Projects provide the means for bringing about realizable changes in products, services, and organizational processes.

3. A regular review of the status of the “portfolio of projects” in an organization provides an excellent assessment of how well the organization is preparing for its future.

4. Failure in project management in the enterprise will impact how well the organization is able to accomplish the “choice elements” in its strategic management strategy.

5. The health of an enterprise can be determined from a review of the “stream of projects” flowing through the organization.

6. The question of the strategic fit of a project is a key judgment challenge facing executives.

7. The use of a project selection framework can help in the selection of projects to support the enterprise’s strategy.

8. Project success is dependent upon an appropriate synergy with the enterprise’s success.

9. The project owner has a key responsibility to maintain surveillance of the status of the projects that are under way to support owner initiatives.

10. Projects are best managed under a project management system philosophy and process.

5.16 PROJECT MANAGEMENT SITUATION—IMPROVEMENT OF PROJECT MANAGEMENT

An electric utility was organized in a very traditional way. Project engineering was carried out in the engineering organization. Any project management that was done was also planned and executed within engineering, a subdivision of the Engineering and Research Department. Although the professionals in the engineering department were excellent project engineering planners and executors, very few of these professionals had any real appreciation of project management—and its broader context in the management of the other functional input areas for a project. Consequently, the quality of project management and leadership was sadly lacking in the company.

Historically, as the company grew, many additional levels were added to the existing bureaucratic structure. Communication between functional “silos” became complex, cumbersome, and slow. Responsibilities were diluted for the overall management of projects for new power plant construction. The cultural ambience of the company could be described as a highly structured, hierarchical enterprise. People tended to focus on the specialization of their functional organizations. Boundaries between the functional organizations became more rigid. As the company grew, its bureaucratic organizational design continued. Fences between functions became higher, and coordination of any particular project became more difficult. Many of the problems in the development and construction of new power plants continued to be difficult.

Senior management, after some major cost and schedule overruns on new power plant construction, concluded that there was no cohesive force to bring together the diverse activities involved in the design, construction, and start-up of new plants. No one individual, other than the CEO, had the authority and responsibility for the building of new plants. Some of the major problems in the management of the acquisition of new power plants included:

• Planning was diffused throughout the organization and no individual had the responsibility for maintaining oversight of the planning for the new plant.

• Although project coordinators had been appointed, the authority of these coordinators was lacking. About all that coordinators could do was to persuade, cajole, or “threaten” the functional people into working in a cooperative fashion in designing, construction, and getting the plant up and running.

• One-way communication prevailed. When a functional element finished its work, the results were “thrown over the organizational wall” to the next function. Concurrent work by the functions on a particular project was limited.

• No person watched the overall project budget. This lack of budget control set the stage for subsequent project cost and schedule overruns.

The stress on the organization and the people was severe. Everyone knew that there must be a better way of dealing with new plant initiatives.

Finally, the senior management of the company established a new project management organizational unit. Some of the key actions undertaken by this new organizational unit included:

• An in-depth assessment of the problems and difficulties being encountered in designing, building, and bringing new plants on-line.

• The development of a strategy on how project management concepts and processes could be implemented in the organization.

• The identification of key individual and collective roles in the organization, particularly those who would be concerned with the management of forthcoming projects.

• The appointment of project teams to evaluate and come up with recommended strategies for the improvement of the management of projects in the enterprise.

• A training program for all key people on the concept and process of project management.

• A commitment on the part of the senior managers, to include corporate directors to provide support and resources to develop a project-driven culture in the enterprise.

• A project review strategy for all projects whereby the project’s cost, schedule, and technical performance would undergo careful scrutiny.

• A commitment by the senior managers of the enterprise that projects would be considered key building blocks in the design and execution of enterprise strategies.

• A plan to go through a formal assessment process of the efficacy of the emerging project management concept and processes within the enterprise.

5.17 STUDENT/READER ASSIGNMENT

1. Evaluate the strategy initiated by this company for the improvement of project management in the enterprise.

2. What could have been done differently in the improvement of the company’s remedial strategy for project management?

3. What would you have done if you had been appointed as the project manager for the remedial strategy for the improvement of project management within the enterprise?

4. What are some of the key issues and considerations to keep in mind when initiating a remedial strategy in a company undergoing a cultural change to emphasize the practice of project management?

5. What project management principles and process could be applied to a situation such as this where an entrenched traditional bureaucracy needs to become a project-driven enterprise, with all the support that a philosophy of project management can provide?