CHAPTER 11

PROJECT AUTHORITY1

“We trained hard…but it seemed that every time we were beginning to form up into teams, we would be reorganized. I was to learn later in life that we tend to meet any new situation by reorganizing and what a wonderful method it can be for creating the illusion of progress while producing confusion, inefficiency, and demoralization.”

PETRONIOUS, ARBITER

GREEK NAVY, 210 B.C.

11.1 INTRODUCTION

In their consulting experiences, the authors have often heard project managers and functional managers lament their lack of sufficient authority to do their jobs. Such laments are not restricted to people in the project environment; others who work in today’s complex organizations often have the same complaint. The authors believe that such complaints have as their root causes the lack of understanding of what authority is, how it is defined, and how to develop the ability to exercise more authority in today’s organizations.

Accordingly, in this chapter authority is defined as consisting of two elements: (1) the legal defined authority; and (2) the authority that one has as a function of knowledge, skills, and attitudes in working with people associated with projects. Authority’s documented definition, how to delegate authority, and the pitfalls of “reverse” delegation are provided in this chapter. In addition, the roles of responsibility and accountability—as key forces in the management of projects—are delineated. The linear responsibility chart (LRC) is suggested as a way to more accurately define individual and collective roles in a matrix organization. The key role that the project work packages play in defining roles in the matrix environment is described, along with a prescription of how to develop and use the LRC as a way to provide a better understanding by people of what is expected of them as they work with and support the project purposes.

11.2 AUTHORITY, RESPONSIBILITY, AND ACCOUNTABILITY

In the previous chapter, we described several organizational design alternatives for managing projects. These descriptions dealt with the structural alignment of the matrix organization. In this chapter we will broaden the concepts of authority, responsibility, and accountability.

Authority is essential to any group or project team effort. The legal authority that is exercised by an individual comes from the organizational position occupied by the individual. Such authority is granted or delegated from a higher authority level in the organization. The ultimate source of authority in organizations can be traced to the owners of the organization. In a business organization, the shareholders elect the board of directors of a company. These directors have the authority given to them by the corporate charter and bylaws to manage the corporation on behalf of the shareholders. The authority of the board of directors is broad, is of a fiduciary nature, and is the starting point for the delegation and redelegation of authority within the organizational structure. The board of directors’ authority role in project management is to study and approve key strategy proposals, particularly those risky projects that involve a substantial portion of corporate resources, and to maintain surveillance of the project during its life cycle.

Project managers face a unique authority challenge in the management of their projects. Usually project managers have only a few people working directly for them—their small administrative staff. Yet the project manager has to practice a subtle form of delegation in letting others—the functional specialists—become the experts and provide the technical input to the project team.

There is little doubt that the degree of control through using legal grants of authority that can be exercised by the traditional line manager is greater than what can be used by the project manager. In the traditional organization the manager would typically have de jure, or legal, authority to schedule and control work, evaluate performance of subordinates, reward and discipline employees, and hire and fire people. Because project teams typically operate in a complex interdisciplinary setting and possess limited command and control authority, the degree of control managers have, is limited. Lacking such traditional line authority, project managers and other members of the project team rely on informal modes of authority through a variety of influence bases.

In a survey conducted by two individuals from the project management community involving the polling of 283 project specialists, project managers, and their functional managers in a variety of technology-oriented organizations, those skills and competencies that are required to effectively lead cross-functional multidisciplinary project teams were identified. A key conclusion of this study was that dealing effectively with project team members and subordinates in today’s project organization requires high levels of managerial competency. An effective project leader needs to be highly analytical to understand technical subtleties, cope with system inconsistencies, and develop insight to manage technical projects effectively.2

A project manager has to watch someone else provide the technical input in which the project manager may have experience and expertise. The project manager must be patient when someone accomplishes a task less proficiently than the project manager might be able to. The project manager must shift from the role of specialist to generalist, a leader in the management functions of planning, organizing, motivating, directing, and controlling. This takes the project manager away from the technical aspect of the project, allowing the project team members to be the experts in the technical work they represent.

11.3 DEFINING AUTHORITY3

Authority is a conceptual framework and, at the same time, an enigma in the study of organizations. The authority patterns in an organization, most commentators agree, serve as both a motivating and a tempering influence. This agreement, however, does not extend to the emphasis that the different commentators place on a given authority concept. Early theories of management regarded authority more or less as a gravitational force that flowed from the top down. Recent theories view authority more as a force which is to be accepted voluntarily and which acts both vertically and horizontally.

Although authority is one of the keys to the management process, the term is not always used in the same way. Authority is usually defined as a legal or rightful power to command or act. As applied to the manager, authority is the power to command others to act or not to act. The manager’s authority provides the cohesive force for any group. In the traditional theory of management, authority is a right granted from a superior to a subordinate.

There are two types of project authority. One, de jure project authority, is the legal or rightful power to command or act in the management of a project. Inherent in this authority is the legal right to commit or withdraw resources supporting the project. The legal authority of a project manager usually is contained in some form of documentation; such documentation of necessity must contain, in addition, the complementary roles of other managers (e.g., functional managers, work package managers, general managers) associated with the project.

Having legal authority is a start. However, to be a successful manager, an individual must develop capabilities in the de facto aspects of authority.

The second type of authority, de facto project authority, is that influence brought to the management of a project by reason of a particular person’s knowledge, expertise, interpersonal skills, or personal effectiveness. De facto project authority may be exercised by any of the project clientele, managers, or team members. In another study it was found that project managers and project personnel believe that expertise and reputation are the most helpful sources of influence in the management of technical projects. It was further determined that technical expertise and organizational expertise are two sources of influence that are available to project managers. Expert power comes to the project manager through background and experience, technical achievement, participation in past projects, and longevity.4

Ford and McLaughlin in their research done in 1992 remind us that classical management theory holds that parity of authority and responsibility should exist. In project management, there may not be such parity across the various stages of the life cycle. They note that few empirical data have been collected to test the hypothesis that parity does not exist and that this lack of parity is the cause of many management problems. In their research report collected from 462 information system managers, the data indicated that in the majority of cases parity did not exist.5

A major part of de facto authority is the ability of the project manager to influence others whose cooperation and support are needed to provide timely resources to support the project. Part of the ability to influence is the competence to work effectively with project team members, functional managers, general managers, and project stakeholders. A project manager must have some technical skill in the technology embodied in the project, not only to participate in the rendering of technical judgments but also to gain the respect of team members who have in-depth technical knowledge and skills. Interpersonal skills provide power to the project manager in influencing the many professionals and managers with whom the project manager works. Developing and maintaining a successful track record that gets people to work with the project manager are, in themselves, a form of power in influencing. The ability to influence is directly related to how others perceive one’s expertise.

Another source of power is to pay attention to and recognize the performance of other people who work with you, such as team members, managers, and stakeholders. In other words, acknowledge the performance of other people just as you would like to have your own good performance recognized. This recognition can take many forms, such as letters of appreciation, phone calls to thank the person, a public thanks in a meeting, comments to a person’s manager, a citation in the person’s personnel file, stopping by the person’s desk to say, Thanks for your help, a personal note of thanks, or some token of appreciation such as a lunch, a book, flowers, or pen and pencil set. Sometimes praising a person’s work to members of the peer group works well; inevitably that praise will be reported to the person.

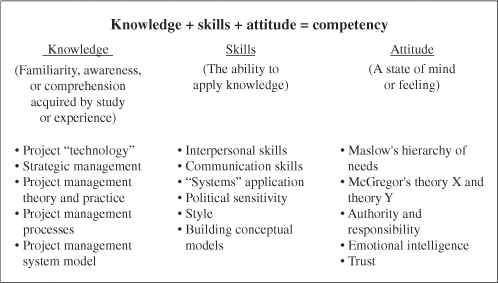

The ability to exercise de facto authority is dependent on the competency of the individual. This competency is essentially a combination of the knowledge, skills, and attitudes that an individual possesses. Figure 11.1 portrays these elements of competency within the context of project management. The reader should note that the elements of knowledge, skills, and attitudes reflected in this figure are described in various chapters of this book.

FIGURE 11.1 Individual competency model.

11.4 POWER

The theory of power can be traced back to sociologist Max Weber. He described three kinds of authority: charismatic, traditional, and bureaucratic. Charismatic authority is where people follow the leader because of his or her inspiration, exemplary character, or behavior, for example, Jesus Christ, Martin Luther King, or Thomas Edison. Often those people who represent this kind of authority are change leaders such as Trotsky. Traditional authority is where obedience is given to an individual who occupies a traditional or inherited position such as in theocracies, patriarchies, and family businesses like the House of Windsor or Anheuser-Busch. Bureaucratic authority (or the role of law) is where power is vested in a hierarchical position and where the authority comes from, say, an elected person who holds office, such as a person holding military rank, or one who occupies an organizational position in the enterprise. All these sources of power do not provide enough clout to get the job done in today’s complex organizations, particularly in those organizations that use alternative teams in their organizational design. Modern organizations depend on the personal power that an individual is able to wield using sources of knowledge, skills, expertise, track record, interpersonal skills, attractiveness, dedication, networks, alliances, and tenacity, to name a few.

Power is not free—it must be earned. Power comes from authority—which depends on the ability of a person to be a leader—and to have the respect of those the leader wishes to lead.

Power coming from the position that one occupies is not enough to get the job done. Hierarchy confers less power because there is less of it in modern organizations. The collective authority that comes from the team and the knowledge and skills of its cross-functional and cross-organizational networks and working arrangements is effective power. In such situations, the team depends on many people over whom there is no formal authority, and peer and stakeholder networks are more important. Indeed, in today’s complex organizations, power is all about empowerment of people to the lowest possible level, which will enable them to carry out their responsibilities without having to check with the boss. The act of empowering people through the delegation process actually results in an increase of power for the one who delegates. In such environments politics, networking, and listening are the core of people skills matter.

Empowerment is like a coin—it has two sides. On the one side is the official authority or legal power that is given to an individual who is occupying an organizational position, such as a project manager and the positions that the members of the project team hold. On the other side of empowerment is the influence that an individual has with regard to the organization’s stakeholders. The first side of empowerment stated above is granted through documentation such as a position description, letters of appointment, a project charter, a policy, and procedure documents. The second side cannot be delegated. It depends on the knowledge, skills, and attitudes of the individuals and the competency that they are able to develop and sustain in the management of the project and in their dealings with project stakeholders.

In Figure 11.1 in the Attitude column, the idea of emotional intelligence is noted. In the material that follows, this idea is explained. Daniel Goleman, in the Harvard Business Review, November-December, 1998 introduced the idea of Emotional Intelligence (EI). He made the important point that IQ and technical skills are important, but EI is absolutely necessary in being successful as a manager. Goleman addressed five considerations in EI:

• Self-awareness The ability to recognize and understand your moods, emotions, and drives, as well as their effect on others. Self-confidence, realistic self-assessment, and a self-deprecating sense of humor are the key elements in self-awareness.

• Self-regulation The ability to control or redirect disruptive impulses and moods; the propensity to suspend judgment—to think before acting. Trustworthiness and integrity, comfort with ambiguity, and openness to change comprise the elements in self-regulation.

• Motivation A passion to work for reasons that go beyond money or status; a commitment to pursue goals with energy and persistence. A strong drive to achieve, optimism even in the face of failure, and organizational commitment are the key rudiments in motivation.

• Empathy The ability to understand the emotional makeup of other people; skills in treating people according to their emotional reactions. Expertise in building and retaining talent, cross-cultural sensitivity, and service to clients and customers are the key factors in empathy.

• Social skill Proficiency in managing relationships and building networks; an ability to find common ground and build rapport. Effectiveness in leading change, persuasiveness, and expertise in building and leading teams are the major components in social skill.

The “bottom line” of EI is to have the ability to understand and manage men and women, boys and girls and to act wisely in human relations. EI keynotes the reality that having superior technical skills is not sufficient for success, the individual must have emotional intelligence as well.

11.5 MATRIX IMPLICATIONS

The matrix organizational design to support the management of projects has been given much attention in the project management literature. Whatever controversy and disenchantment that the matrix design has caused, it cannot be forgotten that the different alternative uses of the matrix that have been tried have been a search for how authority and responsibility could be shared by those organizational entities cooperating in bringing about a focal point to manage the sharing of resources to support organizational projects. Most failures in the use of the matrix have been caused by one or more of the following relative authority-responsibility factors:

• Failure to define the specificity of authority and responsibility of the project and functional people relative to the work packages for which each is solely and jointly responsible.

• Negative attitudes on the part of project, functional, and general managers and team members who support a sharing of authority and responsibility over the resources to be used to support organizational projects.

• Lack of familiarity with the theoretical construction of the matrix and the context in which that organizational design is applied.

• Failure on the part of senior managers to bring about the development of some basic documentation in the organization that prescribes the formal and relative authority of managers and team members associated with a project team.

• Failure to do adequate project team development to include how the team will operate in a cultural ambience of the enterprise where project resources, results, and rewards are shared.

• Existence of an organizational culture that believes and reinforces the traditional command and control notions of authority and responsibility being primarily vertical in their flow downward through the organizational hierarchy.

• Failure on the part of organizational leaders to recognize that the traditional organizational model in the vertical flow of authority and responsibility is rapidly being eroded by the increasing use of computer and communication technology, the increasing pace of change, and the success which alternative organizational designs are enjoying such as found in the use of self-directed teams, quality teams, task forces, and the growing use of participative management to include employee empowerment.

• Failure to modify the traditional pyramid to a design that has fewer levels, with more options for personal movement and flexibility among and within organizational levels. This modification includes the reduction in the number of middle managers and the changes in their roles from one of approval and control to problem solving and facilitation of the means for people to work together to accomplish organizational ends.

• And finally, the failures of managers to promote synergy and unity within and between organizational levels and with outside stakeholders so that resources, results, and rewards can be shared. This type of promotion requires true teamwork, discussion, cooperation of all organizational members, education, and the opening and maintenance of many lines of communication.

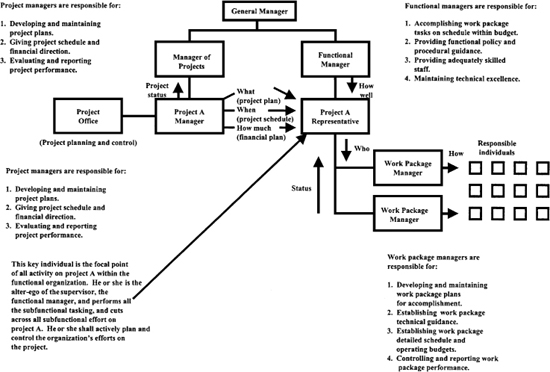

When project management is introduced in an organization, it is essential that these authority roles be understood and accepted by general managers, project managers, and functional managers. This understanding can be facilitated if all the managers concerned jointly participate in the development and publication of a policy document containing a description of the intended authority and responsibility relationships characterized by Fig. 11.2.

FIGURE 11.2 Project-functional organizational interface. [Source: David I. Cleland and William R. King, Systems Analysis and Project Management, 3d ed. (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1983), p. 353.]

During the early days of the matrix organization, it was not uncommon to hear people express their dissatisfaction with the matrix because it was against their religion, and they would quote the biblical phrase about not serving two masters. There was some basis for their concern.

Conceptual guidance for the relationship of the project team member to the project manager and the functional manager can be found in the Bible. Verse 24, Chap. 6, Matthew, states:

No man can serve two masters: for either he will hate the one, and love the other; or else he will hold to the one, and despise the other. Ye cannot serve God and mammon.

This verse probably provides the basis for the evolution of the principle expressed by Henri Fayol as unity of command in which one is expected to receive orders from only one individual. The unity of command principle has provided a key basis in the design of the traditional organizational structure in which authority, responsibility, and accountability flow from the senior person through an organizational hierarchy to the worker who is doing the work of the organizational entity. Violation of this key management principle of unity of command, along with the key principle of parity of authority and responsibility, was considered to be serious, potentially laying down the basis for impairment of the efficiency and effectiveness of the enterprise.

However, as one reads further in the Bible, another insight is gained in how to deal with this apparent violation of a couple of key management principles. In Verse 21, Chap. 22, Matthew, the bible states, “Render therefore unto Caesar the things which are Caesar’s, and unto God the things that are God’s.” By taking license in paraphrasing this verse related to the matrix organization, one could say that the project team members should render unto the project manager the things that are the project manager’s, and unto the functional manager the things that are the functional manager’s. How to do this is explained in Fig. 11.2, in which the relative roles and authorities of the principal players in the matrix organization are portrayed.

A significant measure of the authority of project managers springs from their function and the style with which they perform it. Project managers’ authority is neither all de jure (having special legal foundations) nor all de facto (actual influence exercised and accepted in the environment). Rather, their authority is a combination of de jure and de facto elements in the total project environment. Taken in this context, the authority of project managers has no organizational or functional constraints but rather diffuses from their offices throughout and beyond the organization, seeking out the things and the project stakeholders to influence and control.

11.6 THE POWER TO REWARD

Not only do teams change the culture and the modus operandi of the organization, but also they change the manner in which organizational rewards are provided to people. As people serve on teams and rotate from team to team, performance evaluations are more difficult. In most organizations the team does not yet assume a major part in appraising team performance.6 Of the organizations surveyed by Development Dimensions International, the Association for Quality and Participation, and Industry Week, 46 percent indicated that leaders outside the team handle appraisals, 17 percent said that the responsibility is shared, and 37 percent responded that the team takes the lead in appraising performance.7 On the basis of these surveys, team performance appraisal is changing—teams are accepting such appraisal responsibility—and at the same time management is moving slowly in relinquishing appraisal prerogatives.

11.7 REVERSE DELEGATION

The effectiveness with which project managers exercise authority depends to a large degree on their legal position as well as on their personal capabilities. But there are ways in which project managers can operate to enhance their basic authority. One way is to guard against reverse delegation, which occurs when the person to whom authority has been delegated gives authority back to the delegator. This reverse delegation usually happens under the following conditions:

• The team member wants to avoid risky decisions.

• The team member does not feel that the functional manager is adequately supporting the project.

• The team member lacks confidence, wants to avoid criticism, or feels that the necessary information and resources are lacking to do the job.

• The team member feels that the project manager wants to keep involved in the details of the project.

• The project manager has not been explicit in establishing what is expected of the team member in supporting the project.

Effective delegation is a necessary but not sufficient condition to ensure an effective organizational design to support the project. Organizing a project means many things, one of which is the establishment and maintenance of meaningful authority, responsibility, and accountability relationships among the project team members and other people having a vested interest in the project. Without an adequate, committed process of delegation, there is no effective organization and things can easily fall through the cracks in the project.

11.8 DOCUMENTING PROJECT MANAGER’S AUTHORITY

Project managers should have broad authority over all elements of their projects. Although a considerable amount of their authority depends on their personal abilities, they can strengthen their position by publishing documentation to establish their modus operandi and their legal authority. At a minimum, the documentation (expressed in a policy manual, policy letters, and standard operating procedures) should delineate the project manager’s role and prerogatives in regard to:

• The project manager’s focal position in the project activities

• The need for a defined authority-responsibility relationship among the project manager, functional managers, work package managers, and general managers

• The need for influence to cut across functional and organizational lines to achieve unanimity of the project objectives

• Active participation in major management and technical decisions to complete the project

• Collaborating (with the personnel office and the functional supervisors) in staffing the project

• Control over the allocation and expenditure of funds, and active participation in major budgeting and scheduling deliberations

• Selection of subcontractors to support the project and the negotiation of contracts

• Rights in resolving conflicts that jeopardize the project goals

• Having a voice in maintaining the integrity of the project team during the complete life of the project

• Establishing project plans through the coordinated efforts of the organizations involved in the project

• Providing an information system for the project with sufficient data for the control of the project within allowable cost, schedule, and technical parameters

• Providing leadership in the preparation of operational requirements, specifications, justifications, and the bid package

• Maintaining prime customer liaison and contact on project matters

• Promoting technological and managerial improvements throughout the life of the project

• Establishing a project organization (a matrix organization) for the duration of the project

• Participation in the merit evaluation of key project personnel assigned to the project

• Allocating and controlling the use of the funds on the project

• Managing the cost, schedule, and technical performance parameters of the project8

The publication of suitable policy media describing the project manager’s modus operandi and legal authority will do much to strengthen his or her position in the client environment. In practice, we find many types of de jure authority documentation. A sample of a project/program management charter appears in Table 11.1.

TABLE 11.1 Typical Charter of Program Project Manager (Matrix Organization)

Position Title: Program/Project Manager

Authority

The program/project manager has the delegated authority from general management to direct all program activities. He or she represents the company in contacts with the customer and all internal and external negotiations. Project personnel have the typical dual-reporting relationship: to functional management for technical performance and to the program manager for contractual performance in accordance with specifications, schedules, and budgets. The program/project manager approves all project personnel assignments and influences their salary and promotional status via formal performance reports to their functional managers. Travel and customer contact activities must be coordinated and approved by the program/project manager.

Any conflict with functional management or company policy shall be resolved by the general manager or his or her staff.

Responsibility

The program/project manager’s responsibilities are to the general manager for overall program/project direction according to established business objectives and contractual requirements regarding technical specifications, schedules, and budgets.

More specifically, the program/project manager is responsible for (1) establishing and maintaining the program/project plan, (2) establishing the program organization, (3) managing and controlling the program/project, and (4) communicating the program/project status.

1. Establishing and maintaining the program/project plan. Prior to authorizing the work, the program/project manager develops the program plan in concert with all key members of the program/project team. This includes master schedules, budgets, performance specifications, statements of work, work breakdown structures, and task and work authorizations. All of these documents must be negotiated and agreed upon with both the customer and the performing organizations before they become management tools for controlling the program/project. The program/project manager is further responsible for updating and maintaining the plan during the life cycle of the program/project, including the issuance of work authorizations and budgets for each work package in accordance with the master plan.

2. Establishing the program/project organization. In accordance with company policy, the program/project manager establishes the necessary program/project organization by defining the type of each functional group needed, including their charters, specific roles, and authority relationships.

3. Managing the program/project. The program/project manager is responsible for the effective management and control of the program/project according to established customer requirements and business objectives. He or she directs the coordination and integration of the various disciplines for all program/project phases through the functional organizations and subcontractors. He or she monitors and controls the work in progress according to the program/project plan. Potential deficiencies regarding the quality of work, specifications, cost, or schedule must be assessed immediately. It is the responsibility of the program/project manager to rectify any performance deficiencies.

4. Communicating the program/project status. The program/project manager is responsible for building and maintaining the necessary communication channels among project team members to the customer community and to the firm’s management. The type and extent of management tools employed for facilitating communications must be carefully chosen by the program/project manager. They include status meetings, design reviews, periodic program/project reviews, schedules, budgets, data banks, progress reports, and team collocation.

Source: Harold Kerzner and Hans J. Thamhain, Project Management Operating Guidelines (New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold, 1986), p. 68.

As in the example, care should be taken to delineate the legal position of the project manager. This constitutes an obvious source of power in the project environment. Although this gives project managers the right to exercise that power, the significance of authority under the project-functional interface cannot be understated. Even though project managers may have the final, unilateral right to make decisions in the project, it would be foolhardy for them to substitute their views without fully considering the crystallization of thinking of the other stakeholders in their project. Project managers rarely hope to gain and build alliances in their environments by arbitrarily overruling the team members who contribute to a project. They may not have the control for such arbitrary action. Even if they did, they should be most judicious in using authority in such a manner that the culture in which the project team is operating is not adversely affected.

Authority operates in the context of responsibility and accountability. These concepts are presented in the following material.

11.9 WHAT IS RESPONSIBILITY?

Responsibility, a corollary of authority, is a state, quality, or fact of being responsible. A responsible person is one who is legally and ethically answerable for the care or welfare of people and organizations. A person who is responsible is expected to act without specific guidance or being told to do so by a superior authority. To be responsible is to be able to make rational decisions on one’s own, to be trusted to make such decisions, and to be held liable for one’s decisions.

11.10 WHAT IS ACCOUNTABILITY?

Accountability is the state of assuming liability for something of value, whether through a contract or because of one’s position of responsibility. A professional is held accountable for excellence in the quality of the service rendered to the organization. Project managers have dual accountability: They are held answerable for their own performances and for the performance of people who comprise the project team. One of the basic characteristics of managers is that they are held accountable for the effectiveness and efficiency of the people who report to them.

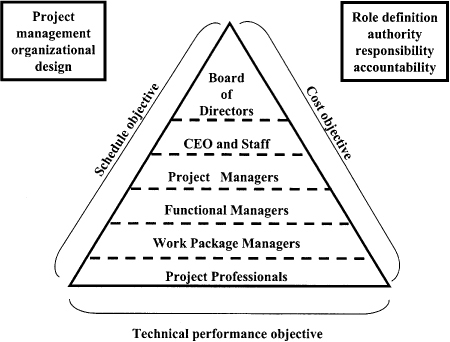

Authority, responsibility, and accountability can rest with a single person or with a group of people. An example of pluralism in this sense is found in the use of a plural executive at the top-management level of organizations such as a management council or the board of directors. The plural executive serves as an integrator of top-management decision making and implementation. The increasing complexity and size of many large organizations have created managerial responsibilities beyond the capabilities of one individual. The plural executive that has been created by organizations usually acts in an advisory capacity to the chief executive by providing stewardship for the strategic management of the company. The specific authority of such plural executives depends on the character establishing such a body. Authority, responsibility, and accountability within the matrix context are the cohesive forces that hold the organization together and make possible the attainment of the organization’s cost, schedule, and technical performance objectives. Figure 11.3 is one way of portraying these forces. The existence of cost, schedule, and technical performance objectives in this figure means that the degree of completeness of authority, responsibility, and accountability at each level in the model can influence any or all of the parameters.

FIGURE 11.3 Project management organizational design.

11.11 PROJECT ORGANIZATION CHARTING9

The organizational model that is commonly called the organizational chart is derided in the satirical literature and in the day-to-day discussions among organizational participants. However, organizational charts can be of great help in both the planning and implementation phases of project management.

11.12 TRADITIONAL ORGANIZATIONAL CHART

The traditional organizational chart is of the pyramidal variety; it represents or models the organization as it is supposed to exist at a given time. At best, such a chart is an oversimplification of the organization and its underlying concepts, which may be used as an aid in grasping the concept of the organization.

Unfortunately, too often the policy documentation describing the role of a project manager will describe this manager’s relationship with the functional organizations as a “dotted line” relationship, which can mean anything one wishes it to mean. For generations, managers have lived with the fiction of dotted lines to describe secondary reporting relationship in the organization. One suspects that managers use a dotted line on an organizational chart because at the time the chart was developed, the relationship had not been completely defined. The use of a dotted-line technique in depicting authority and responsibility gives a manager a great deal of flexibility. The price of this flexibility is confusion and unclear understandings of reciprocal authority and responsibility.

Usefulness of the Traditional Chart

The organizational chart is a means of visualizing many of the abstract features of an organization. In summary, the organizational chart is useful in that:

• It provides a general framework of the organization.

• It can be used to acquaint the employees and outsiders with the nature of the organizational structure.

• It can be used to identify how the people tie into the organization; it shows the skeleton of the organization, depicting the basic relationships and the groupings of positions and functions.

• It shows formal lines of authority and responsibility, and it outlines the hierarchy that fills each formal position, who reports to whom, and so on.

Limitations of the Traditional Chart

The organizational chart is something like a photograph. It shows what the subjects look like, but tells little about how individuals function or relate to others in their environment. The organizational chart is limited as follows:

• It fails to show the nature and limits of the activities required to attain the objectives.

• It does not reflect the myriad reciprocal relationships between peers, associates, and many others with a common interest in some purpose.

• It is a static, formal portrayal of the organizational structure; most charts are out of date by the time they are published.

• It shows the relationships that are supposed to exist but neglects the informal, dynamic relationships that are constantly at play in the environment.

• It may confuse organizational position with status and prestige; it overemphasizes the vertical role of managers and causes parochialism—a result of the blocks and lines of the chart and the neat, orderly flow they imply.

Role definition within the project team is a key consideration in developing the team. When a new team is formed, or when new objectives and goals are developed for the team, or when any key circumstance about the team or its mission changes, such as additional responsibilities, then the definition and understanding of individual and collective roles become important. If the team is intended to be interactive and synergistic, role understanding is critical. Allocating authority and responsibility to the team is an important first step. But the team must understand the authority and responsibility associated with both individual and collective roles, must be committed to those roles, and must be proactive in developing the personal influence that gives added power to the execution of these roles.

How can the individual and collective roles of the project team be established, particularly as team members work with the project stakeholders? Two organizational charts are needed: the traditional chart, which portrays the general framework of the organization, and the linear responsibility chart, which is useful to determine the specificity of individual and collective roles in the organization.

11.13 LINEAR RESPONSIBILITY CHART

The linear responsibility chart (LRC) is an innovation in management theory that goes beyond the simple display of formal lines of communication, gradations, or organizational level, departmentalization, and line-staff relationships. In addition to the simple display, the LRC reveals the work package position couplings in the organization. The LRC has been called the linear organization chart, the responsibility interface matrix, the matrix responsibility chart, the linear chart, and the functional chart.

Six key elements make up the form and process of an LRC:

• An organizational position

• An element of work—a work package—to be accomplished to support organizational objectives, goals, and strategies

• An organizational interface point—a common boundary of action between an organizational position and a work package

• A legend for describing the specificity of the organizational interface

• A procedure for designing, developing, and operating LRCs for an organization

• A commitment and dedication on the part of the members of the organization to make the LRC process work

The LRC shows who participates, and to what degree, when an activity is performed or a decision made. It shows the extent or type of authority exercised by each position in performing an activity in which two or more positions have overlapping involvement. It clarifies the authority relationships that arise when people share common work.

Figure 11.4 shows the basic structure of an LRC, in terms of an organizational position and a work package, in this case “conduct design review.” The symbol “P” indicates that the director of systems engineering has the primary responsibility for conducting the system design review.

FIGURE 11.4 Essential structure of a linear responsibility chart.

11.14 WORK PACKAGES

The work elements of the hierarchical levels of the work breakdown structure are called work packages. They are used to identify and control work flows in the organization, and they have the following characteristics:

• A work package represents a discrete unit of work at the appropriate level of the organization where work is assigned.

• Each work package is clearly distinguished from all other work packages.

• The primary responsibility of completing the work package on schedule and within budget can always be assigned to an organizational unit, and never to more than one unit.

• A work package can be integrated with other work packages at the same level of the work breakdown structure to support the work packages at a higher level of the hierarchy.

Work packages are level-dependent and become increasingly more general at each higher level and increasingly more specific at each lower level.

11.15 WORK PACKAGE–ORGANIZATIONAL POSITION INTERFACES

The organizational positions and the responsibilities assigned to them in carrying out the work package requirements constitute the basis for the LRC. It is developed by specifically identifying responsibilities on each of the work packages. The responsibilities are defined at the work package–organizational position interfaces, by using symbols or letters to depict relationships.

The LRC is a valuable tool as a succinct description of organizational interfaces. It conveys more information than several pages of job descriptions and policy documents by delineating the authority-responsibility relationships and specifying the accountability of each organizational position. However, by far the most important aspect of the LRC is the process by which the people in the organization prepare it. If the LRC is developed in an autocratic fashion, it simply becomes a document portraying the organizational relationships. But if it is prepared through a participative process, the final output becomes secondary to the impacts of the process itself. The open communications, broad discussions, resolution of conflicts, and achievement of consensus through participation provide a solid basis for organizational development and managerial harmony. By the time the LRC is developed in this way, the organization goes through such an “education” that the chart becomes secondary.

11.16 A PROJECT MANAGEMENT LRC

The LRC can be very useful for project managers to use to understand their authority relationships with their project team members. For a simple project, these relationships may be easy to depict; for more complex projects, a series of descending charts from the macrolevel of the project to successively lower levels may be necessary.

Table 11.2 shows an LRC for project-functional management relationships within a matrix organization. The development of such a chart, combined with the discussions that usually accompany such a development, can help greatly to facilitate an understanding of project management and how it will affect the day-to-day lives and activities of the team members.

TABLE 11.2 Linear Responsibility Chart of Project Management Relationships*

In the table the legend depicts the appropriate relationships among the listed positions. This table will serve as a guide to developing specific relationship, based on the organization and the projects.

11.17 DEVELOPING THE LRC

The development of the project LRC is inherently a group activity—getting together with the key people who have a vested interest in the work to be done. The following plan for the development of an LRC has proved useful:

• Distribute copies of the current traditional organizational chart and position descriptions of the key people.

• Develop and distribute blank copies of the LRC.

• At the first opportunity, get the people together to discuss

• The advantages and shortcomings of the traditional organization chart.

• The concept of a project work breakdown structure (WBS) and the resulting work packages.

• The nature of the linear responsibility chart, how it developed, and how it is used.

• A simple way of establishing a code to show the work package–organizational position relationship (getting a meeting of the minds on this code is very important because individuals who believe the code to be either too fine or too coarse will find it difficult to accept).

• The makeup of the actual work breakdown structure with accompanying work packages.

• The fitting of the symbols into the proper relationship in the LRC.

• Encourage an intensive dialogue during the actual making of the LRC. In such a meeting, people will tend to be protective of their organizational “territory.” The LRC by its nature requires a commitment to support and share the allocation of organizational resources applied to work packages. This commitment requires the ability to communicate and decide. This process takes time, but when the LRC is completed, the people are much more knowledgeable about what is expected of them.10

Much of the success of project management depends on how effectively people work together to accomplish project objectives and gain personal satisfaction. The development of a project LRC can greatly contribute to achieving this.

Once assembled, the LRCs can become a “living document” to

• Portray formal authority, responsibility, and accountability relationships.

• Acquaint newcomers with how things are done in the organization.

• Get people committed and motivated so they know specifically what is expected of them.

• Bring out real or potential conflict over territorial prerogatives in the organization.

• Permit people to see the “big picture”—how they fit into the larger whole.

• Facilitate teamwork so people have greater opportunity to see their specific/individual roles on the project in the enterprise.

• Provide a standard against which the project managers and other managers can monitor what people are doing.

11.18 TO SUMMARIZE

The major points that have been expressed in this chapter include:

• Authority is a force that is essential to the functioning of any organization.

• Authority is like a coin. On one side is the legal or de jure authority that is delegated to the organizational position that a person occupies. The other side of the coin is the de facto authority that an individual has by reason of influence in the organization in which he or she works.

• Great care should be taken to prescribe in appropriate documentation the legal authority that attaches to an organizational position.

• The de facto authority that an individual has comes from knowledge, expertise, interpersonal skills, experience, and ability to work cooperatively with the people associated with the project team to include stakeholders.

• Power is an element of authority and can come from several sources.

• A conceptual framework for the proper delineation of roles in the matrix organization can be found in the Bible.

• Project managers—and all managers—should be aware of some of the techniques that people can use to avoid responsibility through the reverse delegation process.

• Some examples of how to document de jure authority in the matrix organization were provided in the chapter.

• Responsibility, a corollary of authority, is a state, quality, or fact of being responsible.

• Accountability is the state of assuming liability for something of value.

• Definitions of the project management role of all principals in the enterprise were given.

• There are serious limitations to the traditional organizational chart—particularly in understanding how individual and collective roles are carried out in the enterprise.

• The material in this chapter includes an identification of the six key elements that make up the form and process of the linear responsibility chart (LRC).

• Individual and collective roles in the project team are key considerations in understanding how the project team is expected to operate in the matrix organizational context.

• An appropriate legend must be developed to use in the LRC to describe the relationships between the work package responsibilities and the organizational position.

• A methodology for how to develop the LRC was provided in the chapter.

11.19 ADDITIONAL SOURCES OF INFORMATION

The following additional sources of project management information may be used to complement this chapter’s topic material. This material complements and expands on various concepts, practices, and theory of project management as it relates to areas covered here.

• William Oncken, Jr., and Donald L. Wass, “Who’s Got the Monkey?,” Harvard Business Review, November-December 1999. According to the authors, the burdens of subordinates always seem to end up on the manager’s back. They tell a manager how to get rid of these burdens. By using the monkey-on-the-back metaphor to examine how subordinate-imposed time comes into being and what the superior can do about it. This is a marvelous article and every professional and manager should be able to relate to the core message contained in the article.

• Kimball Fisher, Leading Self-Directed Work Teams (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1993). There are many similarities between a project team and a “self-directed” team. This book explains how team leadership skills such as coaching, facilitating, group dynamics, and many more of the issues likely to confront the project manager—and the members of the project team—can be managed. The author profiles the most innovative team leader practices from known and successful industrial organizations. The reader should be able to recognize how the knowledge expressed in this book can be applied to the management of a project team.

• David I. Cleland, “Understanding Project Authority,” Business Horizons, Spring 1967. This is believed to be the first article that describes management authority and its use in the matrix organization. The focus of the article is a description of the means for determining how and to whom the “legal right to act” is delegated in those organizations that use project management. Cleland describes “project authority” as applied in the horizontal sense to accommodate the means for empowering the project managers, functional managers, and members of the project team.

• Christopher G. Worley and Charles J. Teplitz, “The Use of ‘Expert’ Power as an Emerging Influence Style within Successful U.S. Matrix Organizations,” Project Management Journal, February 1993, pp. 31–34. The authors briefly review the theory behind the matrix structure and the necessary requirements for its successful implementation. They then review the matter of power and influence in the matrix organization, including a description of prior research on the subject. Then the authors report on the results of a survey of project managers and teams within U.S. matrix organizations.

• Valerie Lynne Herzog, “Trust Building on Corporate Collaborative Project Teams,” Project Management Journal, March 2001, pp. 28–35. This article looks at collaborative team trust building. The article recommends strategies for building corporate team trust. A specific model for trust building in project management is suggested. The author makes the strong point that integrating trust-building strategies into a team environment will help teams and their respective companies become more competitive.

11.20 DISCUSSION QUESTIONS

1. Describe a project management situation from your work or school experience. What role did project authority play in the management of the project? Did authority ambiguities exist?

2. Discuss the importance of clear definitions of project authority.

3. Define authority. Discuss the changing view of traditional authority. Discuss the difference between de jure and de facto authority. What is power?

4. What difficulties do project managers often face in exercising project authority?

5. Discuss the project-functional interface. How can clear lines of authority help in managing this interface?

6. What is meant by reverse delegation? Under what conditions might it be present? How can it be avoided?

7. Discuss the importance of negotiation between project and functional managers.

8. What is the purpose of documenting project authority?

9. What is the difference between authority, responsibility, and accountability?

10. What role does power play in project management? List and discuss some power sources.

11. What are some of the advantages of the traditional organizational chart? What are its limitations?

12. Define the linear responsibility chart in terms of its structure.

13. Define each of the symbols used to describe the responsibilities at the work package–organizational position interface.

14. List the steps involved in the development of the LRC.

15. Why is it important for this development to be a group effort?

11.21 USER CHECKLIST

1. Do the managers in your organization understand the limitations of the traditional chart for managing projects? How do they address these limitations?

2. Are the responsibilities and roles of project team members clear to the project manager and other managers? Are they clear to the team members themselves?

3. Are discussions held between the project managers, team members, and other project stakeholders to clarify authority, responsibility, and accountability? Why or why not? How can these discussions contribute to the success of the project?

4. Think about the various projects within your organization. How is project authority managed? Are there any authority ambiguities?

5. Do you think that the authority of the project managers in your organization is clearly defined? Why or why not?

6. Do the managers of your organization understand the need for definition of authority relationships? Explain.

7. Do the managers of your organization use both de jure and de facto authority? How?

8. Is the project-functional interface effectively managed within your organization? Why or why not? How can clearer lines of authority assist in this management?

9. How is project authority granted within your organization?

10. What barriers to delegation exist on the projects within your organization? How can these barriers be better managed?

11. Is project authority documented? How?

12. What power tactics are used by managers in your organization? Is the use of power tactics productive or destructive toward achievement of organizational and project goals?

11.22 PRINCIPLES OF PROJECT MANAGEMENT

1. There are two types of project authority: de jure and de facto.

2. De jure authority is the legal or rightful power to command or act in the management of a project.

3. De facto authority is the influence brought to the management of a project by reason of a person’s knowledge, skills, and interpersonal skills.

4. Authority and responsibility are shared in the matrix organization among the project manager, functional manager, the general manager, the work package manager, and the professionals on the project team.

5. The focus of authority and responsibility is at the project-functional interface, and centers around the project work package.

6. Project managers should have broad authority over all elements of their projects.

7. The authority and responsibility that is shared in the matrix organization should be documented.

8. Responsibility, a corollary of authority, is a state, quality, or fact of being responsible.

9. Accountability is the state of assuming liability for something of value.

10. The linear responsibility chart is an effective way to determine and assign the authority and responsibility for the management of the project.

11. Authority is a force that is essential to the functioning of any organization.

12. The project manager should have a balance between assigned de jure authority and the capability to exercise de facto authority.

11.23 PROJECT MANAGEMENT SITUATION—PRESCRIBING PROJECT MANAGEMENT AUTHORITY

Authority is the legal right to make decisions that affect the organization and the people in that organization. Responsibility is the obligation to make decisions that will impact the organization and the people in that organization. Authority and responsibility are matched pairs in the management of any organization. Authority and responsibility are provided to other people through the process of delegation. When a manager assumes a new position in an organization, one of the first things the manager should be concerned about is, what authority and responsibility he or she has for making and implementing decisions on the project.

There are two basic types of authority defined and discussed in this chapter: (1) de jure, or the legal right to make decisions; and (2) de facto, or the influence that an individual brings by reason of her or his competency. Indicated below are some of the sources of de jure and de facto authority portrayed in the context of project management:

De jure:

Policy/procedure manuals

Project charter

Letter of appointment as a project manager

Contractual provisions

Project plan

Position dscription

De facto:

Interpersonal skills

Ability to communicate

Team-building skills

Negotiating skills

Political skills

Attitude

Image with project stakeholders

Ability to resolve conflict

Coaching abilities

Emotional Intelligence

11.24 STUDENT/READER ASSIGNMENT

Assume that you have just been assigned as a project manager of a large product development project. One of the first questions that you have is, what authority and responsibility you will have in making and implementing decisions on this project. In order to gain insight into this question, you decide to design a “model” that will describe the specific strategies/actions you would take to capitalize on both the de jure and de facto sources of authority. Describe such a model, and be as specific as you can.

Note that the authors make the point that integrating trust-building strategies into a team environment will help teams and their respective companies become more competitive.