CHAPTER 15

PROJECT MONITORING, EVALUATION, AND CONTROL

“I claim not to have controlled events, but confess plainly that events have controlled me.”

ABRAHAM LINCOLN, 1809–1865

15.1 INTRODUCTION

The unexamined project’s progress cannot be determined without an effective control system. Regular reviews during the life of the project gauges the progress and compares progress to the planned progress to determine the status. Control is a key function for managing the process to assure the progress is satisfactory. The degree of control and frequency of reviews are dependent upon several variables such as project stability, size, complexity, priority, and importance to the enterprise.

This chapter presents a model of the generic steps in the project control cycle, to include a description of these steps. Evaluating the adequacy of project progress and the project management functions being carried out is valuable for anticipating the actual results that the project will produce. Evaluation of the project from a perspective of project planning, project organization, project accomplishments, and project information is suggested. Examination of the project at specified time intervals is discussed. This chapter closes with a recommendation on who should monitor the project evaluation process during the project’s life.

15.2 PROJECT CONTROL CYCLE

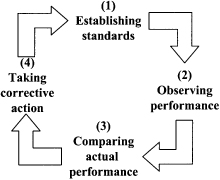

The final management function carried out by the project team is control, which is discussed in this chapter. Control is the process of monitoring, evaluating, and comparing planned results with actual results to determine the progress toward the project cost, schedule, and technical performance objectives, as well as the project’s “strategic fit” with enterprise purposes. The management function of control may be visualized as distinct steps in a control cycle model, as portrayed in Fig. 15.1. Monitoring and control are universal activities indispensable to effective and efficient operation of the control cycle.

FIGURE 15.1 The control system.

Fayol noted that “to control means seeing that everything occurs in conformity with established rule and expressed command.”1 Control is a fact-finding and remedial action process to facilitate meeting the project purposes. Its primary purpose is not to determine what has happened (although this is important information), but rather to predict what may happen in the future if present conditions continue and if there are no changes in the management of the project. This enables the project manager to manage the project in compliance with the plan. The basis of effective project monitoring, evaluation, and control is an explicit statement of the project objectives, goals, and strategies which provide performance standards against which project progress can be evaluated. The following concepts and philosophies are essential elements for the assessment of project results:

• The objective is to develop measurements of project trends and results through information arising out of the management of the project work breakdown structure.

• Performance measurements are always to be tempered by the judgment of the managers and professionals doing the measurement.

• The use of common measurement factors arises out of the status of project work packages consistent with the organizational decentralization of the project.

• Measurements should be kept to a minimum relevant to each work package in the project work breakdown structure.

• Measurements of work packages must be integrated into measurement of the project as a whole.

• Measurements should be developed that are applicable to both current project results and future projections to project completion.

• Measurement should be conducted around previously planned key result areas.

In the material that follows, more information will be given about each of the steps in the control cycle.

15.3 STEPS IN THE CONTROL CYCLE

There are several distinct steps in the control cycle, depicted in Fig. 15.1. These steps in one sense are independent. In another, they are interdependent in the execution of project control. We’ll consider performance standards first.

Performance Standards

Project performance standards are based on the project plan, including at minimum the expectations for the project, established in the project objectives, goals, and strategies, relative to project cost, schedule, technical specifications, and strategic fit. Some key standards in project control include the following:

• Scope of work

• Project specification

• Work breakdown structure

• Work packages

• Cost estimates and budgets

• Master and supporting schedules

• Financial forecasts and funding plans

A project should be evaluated by using several additional key standards:

• Effectiveness and efficiency in the use of the enterprise resources supporting the project. Were the right resources used in the most productive fashion to support the project?

• Expected technical performance quality of the product or service resulting from the project. Do the project results provide value to the customer?

• Development cycle time. Is the project being developed in sufficient time to meet or preempt competition?

• Do the project results complement existing products and services being provided in the marketplace?

• It is important to recognize that performance standards are derivatives of project planning, as well as organizational planning, keynoting again the basic (but often forgotten) principle that proper planning facilitates proper control.

Performance Observation

Project performance must be sensed and that is where performance observation comes into play. Performance observation is the receipt of sufficient information about the project to make an intelligent comparison of planned and actual performance. Information on project performance can come from many sources, both formal and informal. Formal sources include reports, briefings, participation in review meetings, letters, memoranda, and audit reports. Informal sources include casual conversations, observations, and listening to the inevitable rumors and gossip that exist within the project team and in other parts of the organization. Talking and listening to the project stakeholders can be a useful source of information on the project’s status. Informal meetings for lunch or coffee breaks can help provide the total information “system” the project manager needs to have to know fully what is going on. Both formal and informal information sources are needed to keep up with the project’s status. Feedback during performance observation consists of relevant data on the result of the project management process and provides the basis for making a judgment on performance through doing comparative analysis.

The process of performance observation can take many forms, such as the following:

• Regular receipt of formal information reports on the project’s performance, obtained through formal project reviews, along with other supporting formal information.

• Walking the project, sometimes called “kicking the tires,” and observing what people are doing as they work on the project in their various capacities.

• Conversations with people, especially with the project manager taking the lead, to ask the project stakeholders on a regular basis about “how things are going on the project.”

• From regular formal project meetings where progress is discussed on the project to the identification of remedial action that is required and who will take the responsibility for following up on the correction of the perceived deficiencies.

• Informal sources talking and listening to project team and other stakeholders on a regular basis to seek their assessment of “how the project is going.”

• Briefings about the project concerning specific problems and opportunities that have arisen or are expected to arise concerning the status of the evolving strategy of the project.

• Maintaining a concentrated effort to listen and listen and listen to what project stakeholders are saying about the project.

Comparing Planned and Actual Performance

Comparing planned and actual performance based on the desired project standards gives the opportunity to get answers to three key questions about the project:

• How is the project going?

• If there are deviations from the project plan, what caused these deviations?

• What should be done about these deviations?

Assessment of the project’s status is an ongoing responsibility of the project team and the senior managers. Information obtained by performance observation is compared with the performance standards laid down in the project plan and when analyzed, forms the basis for reaching a judgment about the project’s status and whether corrective action is required.

Corrective Action

Corrective action can take the form of replanning, or reallocating resources, or changing the way the project is managed and organized. The corrective actions that are available to the project manager center on the cost, schedule, and technical performance parameters of the project. The project owner may have finalized one or more of these parameters. Correcting a problem with one of the parameters of the project may have reverberations on one or both the other parameters. Such potential reverberations should be considered by the project team when the alternatives for corrective action are being studied.

15.4 MONITORING AND EVALUATION

Monitoring and evaluation to collect information are integral to control, as depicted in Table 15.1, and are key companions of the control function. The questions listed in Table 15.1 are intended to stimulate discussions and generate information about the project. Monitoring means to keep track of and to check systematically all project activities. This enables the evaluation, an examination and appraisal of how things are going on the project. As a direct link between planning and control, the monitoring and evaluating functions provide the intelligence for the members of the project team to make informed decisions about the project performance. Monitoring should be designed so that it addresses every level of management requiring information about project performance and reflects the work breakdown structure of the project. Each level of management should receive the information it needs to make decisions about the project. In addition, monitoring should be consistent with the logic of planning, organizing, directing, and motivating systems on the project.

TABLE 15.1 Key Project Control Questions

1. Where is the project with respect to schedule, cost, and technical performance objectives and goals?

2. What is going right (according to plan) on the project?

3. What is going wrong on the project?

4. What problems are emerging?

5. What opportunities are emerging?

6. Does the project continue to have a strategic fit with the enterprise’s mission?

7. Is there anything that should be done that is not being done?

8. Are the project stakeholders comfortable with the progress of the project?

9. How is the project customer image—is the customer happy with the project’s progress?

10. Has an independent project evaluation been conducted?

11. Is the project being managed on a total “project management systems” basis?

12. Is the project team an effective organization for the project’s work?

13. Does the project take advantage of the enterprise’s strength?

14. Does the project avoid a dependence on the weakness of the organization?

15. Is the project making money for the organization?

Monitoring means to make sure sufficient intelligence is gained on the status of the project so that an accurate and timely evaluation of the project can be conducted. Several issues have to be addressed by the project team in considering their monitoring and evaluation responsibilities:

• What should be monitored and evaluated.

• What monitoring tools should be used.

• When should the project be monitored and evaluated.

• Who should monitor and evaluate.

• Where should the monitoring and evaluation be carried out.

All activities of the project and its stakeholder environment should be monitored and evaluated, of course, done on an exception basis through the delegated responsibilities of the project team. A framework for doing the evaluation can consist of a series of key questions about the project, which must be answered on an ongoing basis. If the project team can ask questions and get timely, credible answers, then the chances of knowing the project’s true status are enhanced considerably.

Questions of the type shown in Table 15.1 can be used during regularly scheduled project review meetings to motivate discussions among the project team members and to encourage them to think retrospectively as well as prospectively about the project. Such thinking will prompt the team members to evaluate the project. Project review meetings should be held regularly by the project owner, senior managers of the project organization, the project team, the work package managers, and the project professionals.

A key question in reviewing any project is the degree of success that the project management team has had in the development of an integrated project management system for the project. Project evaluation, to be effective, must look both at the efficacy of the parts of the project (the subsystems) and at the project totality, expressed in such factors as attainment of the project’s technical performance objective, completion schedules, and final cost. Monitoring and evaluation of the project require that the project team look inward to the project and the sponsoring organization as well as outward to the stakeholders and the general “system” environment in which the project is found.

The avoidance of cost and schedule overruns should be one of the key outcomes of any project control system. Following are examples of how projects were able to stay within budget or exceed budget:

• The $630 million upper-atmosphere research satellite is one of two large U.S. space projects that was kept on cost and schedule in part because the project team combined political savvy with technical conservatism to guard the project from controversy and keep it moving in the right direction. To cut costs and improve reliability, the spacecraft was designed by using technology that had been used before, such as plug-in modules for propulsion, communications, and navigation. By keeping a low profile, the project proceeded without controversy. In addition, much of the success of this project can be attributed to a good plan, which is always an important factor in controlling the use of resources on a project and in determining the success of a project.2

• Another project, the Earth Observing System (EOS), an environmental satellite project, was, by some estimates, $13 billion above its original cost projections and 5 years behind schedule. Its managers overestimated their political support and underestimated the technical challenge of the project. This project became mired in controversy from the start; the space agency proposed to build six of the largest, most complex satellites ever conceived for EOS and to back them up with one of the world’s most sophisticated computer systems. The project was taking so much money that lawmakers and scientists feared it would take away funds from other projects considered to be more worthy. Although the White House and Congress approved the start of the project, both backed off as the project’s risk level became apparent.3

15.5 MANAGEMENT FUNCTIONS EVALUATION

You can use management-related activities to address representative key questions to evaluate the project. Assuming that a project management function’s viewpoint is used as a baseline for evaluating a project, what should be measured?

Answers to questions such as the following can give insight into what should be measured and how well the project is doing.

Project Planning

• Are the original project objectives and goals realistic?

• Is the plan for the availability of project resources adequate?

• Are the original project schedule and budget realistic?

• Is the plan for the organization of the project resources adequate?

• Are there adequate project control systems?

• Is there an information system for the project?

• Were key project stakeholders brought into project planning?

• Was facility planning adequate?

• Was planning completed before the project was initiated?

• Were potential users involved early in the planning process?

• Was there adequate planning for the use of such management tools as project control networks (CPM/PERT), project or study selection techniques, and information systems?

Project Organization

• How effective is the current organizational structure in meeting the project objective?

• Does the project manager have adequate authority?

• Is the organization of the project office staff suitable?

• Have the interfaces in the matrix organization been adequately defined?

• Do key project stakeholders understand the organization of the project office?

• Have key roles been defined in the project?

Project Management Process

• Does the project manager adequately control project funds?

• Are the project team personnel innovative and creative by suggesting project management improvements?

• Does the project manager maintain adequate management of the project team?

• Do the project team people get together on a regular basis to see how things are going?

• Does the project office have an efficient method for handling engineering change requests?

• Does the project staff seek the advice of stakeholders on matters of mutual concern?

• Have the project review meetings been useful?

Project Accomplishments

• To what extent have the original project goals been achieved?

• How valuable are the technical achievements?

• How useful are the organizational and/or management achievements?

• Are the project results useful in accomplishing organizational objectives?

• Are the results being implemented?

• Are the users being notified properly?

• Is the customer happy with the project results to date?

Effective project control can be carried out only if there is adequate information about the project that can be used for monitoring and control.

Project Information

The project team requires a project control system that provides key information on the status of the project. It needs several key systems to provide such information:

• An equipment, labor, and material information system that provides the basis for the effective and efficient utilization of the workforce on the project. These cost factors are usually the large contributors to the overall project cost. Their status should be known to the project team and the owner.

• A cost control system so that the project team can determine whether the costs are in line with the project plan and to help understand deviations that may occur.

• A schedule control system to identify schedule problems so that cost-effective trade-offs can be carried out as needed.

• A budget/financial planning/commitment approval system so that the data on the commitment, expenses, and cash flow of the project can be collected and analyzed and appropriate remedial action taken.

• A work authorization system that provides for the allocation of project funds to the functional organizations and outside vendors.

• A method of using the collective judgment of team members to judge the progress being made to satisfy the project’s technical performance objective. To reach this judgment, the progress of the individual work packages must be assessed along with the progress on the integration of all work packages. This judgment can best be made by the project team in a group session by reviewing and assessing all the information the team has assembled and then reaching an informed judgment of where the project stands, for example, on project costs.

15.6 WHEN TO MONITOR AND EVALUATE

When should you monitor and evaluate the project? The answer to this question is simple and straightforward. Monitor and evaluate the project during its entire life cycle.

For example, the James Bay project had management controls that tied together all the project efforts from conceptual design through contract closeouts. Furthermore, the engineering department of the James Bay Energy Corporation (the project management organization for the James Bay project) conducted quarterly board of consultants meetings to review engineering designs.4

Project evaluation is a process that extends throughout the project life cycle through to a “postmortem” that assesses the capability of the project to support organizational strategy in terms of a useful product or service, which supports the organizational mission. There are four major types of project evaluation:

• Preproject evaluation for the selection of a project to determine if it shows promise to the objectives and overall strategy of the organization or enterprise.

• Ongoing project evaluation for measuring the status of a project during its life cycle.

• Project completion evaluation for an immediate assessment of success upon project completion.

• Postproject evaluation for a down-the-road assessment of project success after the dust and confusion have settled.

15.7 PLANNING FOR MONITORING AND EVALUATION

Clearly, part of project planning should include the development of a strategy on how the project will be evaluated during its life cycle. This planning is just as important as the planning for any other aspect of the project. In approaching the development of project evaluation strategy, there are several key requirements: the inclusion of an evaluation policy and the process, the commitment of all key managers involved in the project to an evaluation strategy for evaluation methodologies, and the use of both inside and independent evaluators who have the professional credentials to do a credible job of the evaluation process.

Not only does a periodic evaluation of the project as a normal and expected responsibility of the project team make good sense, but also evaluations on a periodic basis to examine the rationale and mandate for the project provide benefits. Such evaluations show that the principal managers have a concern for the degree to which the project objectives and goals are being achieved and the identification of any shortcomings in the management of the project. By having the principal managers insist on periodic and special evaluations, an important message is sent throughout the organization. A project owner who has contracted for the engineering, design, and development of the project’s product would be foolhardy not to insist on regular and special evaluations of the project’s progress. Indeed, a prudent project owner would actively participate in such evaluations.

15.8 WHO MONITORS AND EVALUATES?

The principal responsibility for project monitoring and evaluation rests with the project team and the project owner. The manager who has “general management” or “project owner” jurisdiction also shares in the residual responsibility for keeping informed on what is happening on the project. Where are the monitoring and evaluation carried out? Simply put, as close as possible to the action on the project at the individual professional’s level where the work is being done, as well as at:

• The work package level

• The functional manager’s level

• The project team level

• The general manager’s level

• The project owner’s level

Each successive level’s monitoring and evaluation are more integrated, dealing with the project’s total schedule, cost, and technical performance objectives. Finally, the project’s strategic fit in supporting the owner’s mission is evaluated.

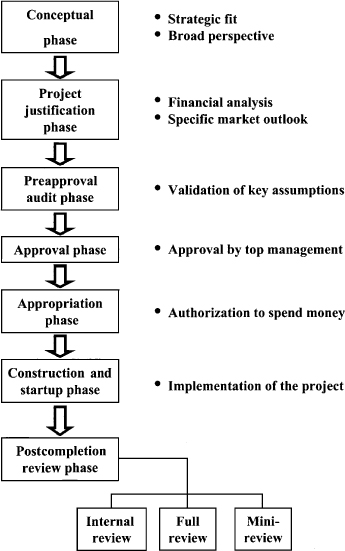

15.9 POST-PROJECT REVIEWS

Much can be learned about the efficiency and effectiveness with which projects are managed in the organization through a postproject review (PPR). Postproject reviews are gaining more favor in the management of projects. In the nuclear power plant industry, such reviews have become commonplace to determine which project costs have been incurred reasonably, so the public utility commission can decide which costs can be passed on to the consumers of the nuclear plant’s electricity. Other industries are conducting PPRs in the capital budgeting process. One view of this process is depicted in Fig. 15.2.

FIGURE 15.2 PPRs in the capital budgeting process. (Source: Surendra S. Singhvi, “Post-Completion Review for Capital Projects,” Planning Review, May 1986, p. 37.)

PPRs take a large view to examine the rationale for the project in the first place. The PPR also examines the strategic fit of the project into the overall organizational strategy. PPRs offer insight into the success or failure of a particular project as well as a composite of lessons learned from a review of all the projects in the organization’s portfolio of capital projects. At British Petroleum, PPRs have become an integral part of the corporate planning and control process. British Petroleum has learned valuable lessons on each capital project, and general principles about project management have emerged over the 10 years that British Petroleum has been conducting such reviews. These principles are as follows:

•Determine costs accurately.

• Anticipate and minimize risk.

• Evaluate contractors more thoroughly.

• Improve project management.5

If the project plan contains a specific strategy for the conduct of PPRs, there will be subtle benefits through the discipline and team effort needed to do an adequate review. If the project team members know that the success (or failure) of the project will be evaluated at the project’s completion, they should be motivated to do a better job of managing the project during its life cycle. These attitudes will permeate the culture of the organization and improve decision making in the planning process for new projects to support the organizational strategies. This should result in better capital investment decisions and should improve the organization’s competitive chances.

15.10 CONFIGURATION MANAGEMENT AND CONTROL

Most people recognize the need to plan and control budgets, schedules, and even performance specifications for a system that is under development. However, in complex projects, the elements that must be controlled are much more varied and detailed than is generally understood.

Configuration control (or engineering change management) represents one such level of specificity. In the development of complex projects, changes in the configuration of hardware and software reverberate through the system, causing problems with budgets, schedules, and so forth. Thus, such changes must be directly addressed and controlled. It is inadequate to attempt to effect control solely at a higher level.

Configuration management is the discipline that integrates the technical and administrative actions of identifying the functional and physical characteristics of a system (or product) during its life cycle. It is directly related to the project technical performance objective. Configuration management provides for control of changes to these characteristics and provides information on the status of engineering or contract change actions.

The essence of configuration management comprises three major areas of effort: configuration identification, configuration status accounting, and configuration control.6

Configuration Identification

Configuration identification is the process of establishing and describing an initial system baseline. This baseline is described in technical documentation (such as proposal terms, specifications, and drawings). The identification function provides for a systematic determination of all the technical documentation needed to describe the functional and physical characteristics of items designated for configuration management. Configuration identification also ensures that these documents are current, approved, and available for use by the time needed.

The concept of a baseline system requires that the total system requirements and the requirements for each item of the system be defined and documented at designated points in the evolution of the system. An evolutionary life cycle of the system from paper study to inventory items is prepared to plan for development and production status and to permit changes in the scope of the system.

There must be a recognized and documented initial statement of requirements. Once stated, any change in the system’s requirements must be documented so that the current status may be fairly judged for performance requirements. A baseline is established when it is necessary to define a formal departure point for control of future changes in performance and design. Configuration at any later time is defined by a baseline model, plus all subsequent changes that have been incorporated. This baseline model provides a point of departure to manage future engineering and/or contract changes.

Configuration Status Accounting

Configuration status accounting is the process of recording and documenting changes to an approved baseline to maintain a continuous record of the status of individual items that make up the system. Configuration status accounting also shows which actions are required and which engineering changes are complete. Status accounting will identify all items of the initially approved configuration and then continually track authorized changes to the baseline.

Configuration Control

Configuration control is the process of maintaining the baseline identification and regulating all changes to that baseline. Configuration control prevents unnecessary or marginal changes while expediting the approval and implementation of those changes that are necessary or that offer significant benefits to the system. Necessary or beneficial changes are typically those that correct inefficiencies, satisfy a change in operation or logistics support requirements, effect substantial life cycle cost savings, or prevent or eliminate slippage in approved scheduling.

A configuration control board acts on all proposed changes. The configuration control board recommends final decisions on engineering changes and installs good engineering change discipline in the system. This board can provide a single-point authority for coordinating and approving engineering change proposals.

There are two basic potential costs of a contract change such as an engineering change. The first is the direct cost of the change itself, expressed in performing the substantive work of the change, for example, redesign, engineering, and construction/manufacturing. The second is related indirectly to the change order, or the “ripple effect,” for example, additional supervision, consequential damages, decrease in productivity during the implementation of the substantive work, and so on.

The approach to configuration management in the context of engineering change management is undergoing change as concurrent engineering techniques continue to be used. In a team charged with the responsibility of planning and executing a concurrent engineering initiative, an ongoing configuration management process is carried out. As the interdisciplinary concurrent engineering team does its work, an ongoing design review continues on a regular basis. Also, because there is a much closer coordination and working relationship between the design and manufacturing disciplines, there are likely to be fewer engineering changes on the project. Most if not all compromises between design engineering and manufacturing engineering have been studied and resolved by the team before the product is committed to production.

15.11 PLANNING AND CONTROL IMPLICATIONS FOR PROJECT SUCCESS OR FAILURE

The success or failure of a project is directly related to is objectives and goals. These objectives and goals establish the baseline by which one can measure degrees of success and degrees of failure. Typically, there is not a simple success or failure of a project because successes do not meet all stakeholders’ expectations and failures provide some benefits, but perhaps at a cost that is more than expected.

In the initial planning stage, cost, schedule, and technical performance goals and objectives are established. In a stable project, these goals and objectives remain the same through completion. A stable project where there is no migration of the goals and objectives, which includes the initial requirements, is a rare situation. Projects that “grow” in requirements and “discovered” work may be the norm.

From an organizational point of view, a project brings benefits that are determined through the business process for identifying and quantifying jobs. The goals and objectives for the project relate directly to the “business” and its strategic objectives. Changes in the business direction or changes by a client may materially alter the need for a project, its benefits to both the organization and the client, or the number of benefits delivered. Business objectives and project objectives should be in alignment, although they are not necessarily the same.

Criteria for project success are established from the business requirement and relate to the three areas of the project’s scope—cost, schedule, and technical performance. An example of this could be a new venture to build an electric car for commuters. Objectives could be:

• Schedule. Build and test a prototype electric car in 12 months.

• Cost. The budget for the project is not to exceed $1.4 million.

• Technical performance. The prototype car will operate for 3 hours between charges, recharge the batteries fully in less than 6 hours from 110-volt AC current, transport 400 pounds of weight to include the operator, accommodate two people (driver and passenger), have a speed of at least 65 mph on the highway, incorporate all safety features for highway operation, and meet all U.S. DOT requirements.

Criteria for success for the business requirement could be:

• Build and sell 2000 electric automobiles for sale in the year 2008.

• Generate total revenues of $20 million in 2008.

• Establish dealership relations for sales and maintenance of the electric cars.

• Double sales for the year 2009.

Success for the project is stable and the project manager can plan and work toward meeting the objectives. Any change to the business requirement may affect the project’s objectives. Some examples could be:

• The sales force underestimated the demand for an electric car. The car is needed in 2008 to meet competitors that are building a similar model. The project schedule is negatively impacted and the prototype must be built and tested in 6 months.

• The competition is building a car that will operate on the average for 4.5 hours. The technical specification changes to 5 hours of operation with the same weight capacity and recharge time. This would drive the technology for the project and perhaps look at means of reducing the use of electrical energy and improving on the batteries’ storage capacity.

• The prototype car does not include the aesthetic features that give the car an image and the marketing department wants the prototype to look like a production model. This will permit smooth transition from the prototype to production with only a little engineering and design change. The project’s technical objectives may be significantly changed to require more design work, more engineering, and greater expenses for the “production prototype.”

15.12 RESULTS OF PROJECTS—SUCCESS OR FAILURE

Project success or failure appears to be a simple equation: The project met its cost, schedule, and technical performance goals. However, success or failure is relative to the interests of the party viewing the project. Each stakeholder can have interests that do not necessarily agree with another stakeholder. These potentially conflicting views can result in one person calling a project a success and another calling it a failure.

A brief look at criteria that different stakeholders may use in assessing the success of project is helpful to understand the outcome of projects. Some of the stakeholder criteria for success could be:

• Customer or user. The product of the project meets my needs and has all the characteristics, features, attributes, and functions required. Success is receiving the full capable product on time and at a reasonable price.

• Senior corporate management (sponsoring organization). The project generates a reasonable monetary contribution to the organization (i.e., profit or fee), the product performs to the customer’s satisfaction, the project and product add to the organization’s capability through improved processes, and the organization’s image is enhanced to promote future sales. Success is with project results that create value in the marketplace.

• Project manager. The project is completed within budget and schedule while meeting the technical performance criteria, the customer is pleased, and senior management is pleased with the results. Success is measured against the project’s objectives of cost, schedule, and technical performance.

• Project team. The project is completed and members are rewarded for their contribution to the effort. Success is that each member receives a reasonable compensation for his or her work and grows professionally through added knowledge, skills, and experiences.

• Second-party stakeholders. The project and its product do no harm to their interests. Success in this instance is when there is no disruption of these stakeholders’ perceived interests.

Generally, project success is measured by the cost, schedule, and technical performance objectives. Success of the project may also be measured through the by-products that contribute value to stakeholders. R&D projects, for example, will often have by-products that can have strategic value to the sponsoring organization. The strategic by-products may be such items as a database of collected information on a phenomenon of nature—take the space program experiments as an example.

Some projects labeled complete failures may have by-products that can be “harvested” for future project work and future business. These benefits may not be stated in a project report, but can have a direct influence on an organization’s future capability within a given field or discipline. These by-products may indirectly deliver benefits greater than the project, whether it is considered a success or a failure.

Some by-products that may result from projects are as follows:

• New technical or business purposes that improve project management and operations

• Trade secrets and practices that improve work capacity

• Patents and copyrights (intellectual property) for the developer or customer

• New uses for developed products and services

• Enhanced corporate image for building products

• Individual and team experiences in project management processes

• Corporate knowledge of new technology and manufacturing processes

• Best practices in project management

• Trained workforce (project teams, individuals, senior managers)

15.13 EXAMPLES OF PROJECT SUCCESS/FAILURE

Discussion of project success or failure gives a better understanding of project results and the relative nature of defining the outcome. Some examples of project success/failure from literature are helpful toward understanding the current method of classifying projects in discrete success or failure categories. There are seldom grades or degrees of success when following the project’s objectivescost, schedule, and technical performance.

Thomas and colleagues state at a research conference in June of 2000 that a survey revealed the following:

• More than 30 percent of projects surveyed are canceled before completion.

• More than one-half the completed projects have cost overruns nearly double the original budget.

• More than one-half the completed projects exceed the schedule by more than twice the planned time.

• Lack of senior management commitment in more than 1400 surveyed organizations was a key factor for project failure.7

Thomas and her colleagues identify one problem that challenges successful projects: Senior managers do not connect project management’s value to the organization’s goals and objectives. The use of project management appears to be a response to internal crises rather than a formal strategy to promote business.

A review of the record concerning project success and failure reveals that most projects have problems that result in delays in schedules, cost overruns, and/or inability to attain the desired technical objectives. For example:

• In an assessment of approximately 8400 projects it was determined that about one-third were outright failures, 50 percent were undergoing remedial strategy and would likely overrun their initial cost estimates by almost 200 percent, and only 16 percent were done on time, within budget, and meeting their technical performance specifications.8

• Another assessment states that a series of studies conducted over the years indicated the presence of an ever-increasing phenomenon of project “failure.” The study presented what seemed to be the “big four reasons of project failure,” namely, inadequate project definition, lack of general information, poor scheduling and allocation of resources, and loss of control of the project.9

• There have been many causes of failure in projects. Perhaps the most general cause—and the most probable reason—is argued to be that “most project failures occur because basic and obvious principles of management are ignored.”10

The past editor of the Project Management Journal provides insight into the general state of performance on a variety of projects drawn from diverse environments. For example:

• The General Accounting Office of the U.S. government claims that there has been a consistent pattern of overruns beyond the initial baseline standards in federal government–funded projects.

• The Rand Corporation studies show a consistent pattern of overruns in technically complex projects, whether in aerospace or construction.

• U.S. nuclear power plants, tunneling, highway, water, building, defense, and other projects experience overruns.11

Project success and failure are relative terms. Failure is the condition or fact of not achieving the desired end or ends; success is the achievement of something desired, planned, or attempted. Whether a project is a success or a failure is in the eye of the beholders, that is, those individuals, enterprises, agencies, institutions, who are the stakeholders. For example:

• A project that overruns its cost and schedule and experiences delays in attaining its technical performance objectives may be considered a success if the project’s outcomes ultimately fit into the choice elements of the organization.

• A project that experiences problems in attaining its desired objectives in costs, schedules, and technical objectives—and is not available to fit into the strategic management purposes of the enterprise—would likely be considered to be a failure.

• A project that is terminated prematurely because its final outcome is expected to be inconsistent with the choice elements of the enterprise could be considered to be a success by the strategic managers of the enterprise.

• An individual who gains valuable experience in serving on a project team could view the project as a success—regardless of its ultimate outcome.

• A key project stakeholder, such as an environmentalist concerned with the pending construction of a nuclear power plant, could view the project as a failure even though the plant finally comes on line.

• The manager of a financial institution who sees that a project’s financial management is inadequate could view the project as a failure.

• A project team could feel strongly that the project they are working on is a success if extraordinary problems on the project had been finally solved. Yet, if the project were canceled because it no longer promised to make a suitable contribution to the strategic choice elements of the enterprise, the project team might well feel that the project was a failure because of its early termination.

15.14 THE CAUSES OF SUCCESS OR FAILURE

A project’s success or failure should be attributed to the philosophy of management that is carried out during the project life cycle:

• By those strategic managers who have responsibility for the management of the enterprise as if its future mattered—to include continuous oversight of the project in its journey toward becoming a potential contributor to the choice elements of the enterprise.

• By the project manager and the team who have responsibility for the attainment of the project’s cost, schedule, and technical performance objectives.

If we take these two types of managers and investigate their responsibilities further, we find that the strategic managers are responsible for:

• Providing adequate resources to support the project during its life cycle

• Defining how the project results will contribute to the choice elements of the enterprise

• Establishing and defining how the individual and collective roles of the project manager, the project team members, and the functional managers are to be carried out

• Providing for a regular review of the emerging project cost, schedule, and technical performance results as well as the likely fit of these results into the future of the enterprise

• Maintaining a general perspective of the satisfaction that the stakeholders have with the project

• Promoting a culture that supports the management of projects in the enterprise

The project managers are responsible for:

• Use of project resources in an effective manner that enhances the probability of the project achieving its schedule, cost, and technical performance objectives

• Keeping the project stakeholders informed of the progress of the project as needed, and to the extent possible, managing the project stakeholders to gain and hold their support for the project

• Maintaining ongoing interfaces with organizational units to develop and continue support of the project

• Enhancing the knowledge, skills, and attitudes of the project team members to increase the effectiveness of their support of the project

• Keeping the enterprise managers informed of the status of the project at all times

• Developing and using appropriate information systems to keep project stakeholders informed of the status of the project

An empirical investigation of the sources of major project problems found that project managers felt a lack of ability to influence external stakeholders. Comments suggesting how external stake-holders could be influenced in even minor ways were rare.12

There have been many attempts to provide a description of the success factors and failure factors for projects. A few rigorous research initiatives have been designed and executed to identify the critical success factors.

The U.S. Air Force’s acquisition of the T-3A “Firefly” trainer was a troubled project. Rather than develop a new aircraft, the Air Force decided to save time and money by buying a commercial off-the-shelf (COTS) trainer. But significant aircraft modifications undermined the integrity of the COTS strategy.13 Decisions made early in a project determine future success. Missteps in early phases will cause trouble later in the project’s life cycle.

There are four lessons learned from this project:

• Any project must be managed as a system of interrelated parts.

• A project strategy must be flexible to accommodate changing circumstances.

• Testing must be done in realistic environments.

• Concurrency carries with it benefits and dangers.

Evaluating the success of projects is rarely a precise science. Examples of project ambiguity abound: The Hubbell Telescope started its operational life as a sort of national joke, a case study of project failure. Yet today it continues to reveal never-before-seen views of the heavens, views unobtainable from any other source. At its completion, the Sydney Opera House was seen by most as a stupendous failure: a music hall with poor acoustics, stunningly over cost and behind schedule. Decades later, that same structure is a unique national treasure, its massive cost and schedule overruns long ago forgotten.

Andersen and Jessen provide a scheme for project evaluations that can be used as a checklist or guide from the start of a project through its postproject reviews. Sixty items provide critical statements that could be used to validate the planning, execution, and control phases of projects. Their information is interpreted and summarized here to provide the essence of the assessment checkpoints:14

• Project scope. Mission and goals are clearly stated and unambiguous in their wording. The mission and goals cannot be misunderstood because the originator uses concrete terms that lead to a clearly defined, deliverable product or service.

• Terms of reference. Economic and time parameters are clearly stated for the project and the product is sufficiently defined. All stakeholders are apprised of the project’s parameters and agree to the key goals and objectives. There is a well-documented business strategy for the project.

• Project planning. The plan is simple and easily understood with milestones. The strategy is embedded. It has sufficient detail to delineate responsibilities and make clear the direction is understood. Adequate tools are incorporated to support the implementation process.

• Project organization. A project organization chart depicts the hierarchy for responsibility as well as linkages to other departments or parties involved in the project. Show coordination lines to other organizations. Ensure the organization does not inhibit communication with key decision makers or supporting organizations.

• Project execution. Implementation of the project plan by designated individuals is in accordance with the procedures prescribed. Changes to the plan are made in a timely manner and communicated to all stakeholders. Senior management stays involved in the decision making and stays apprised of the project’s progress. The project team maintains awareness of progress and status.

• Project control. Active tracking of progress, including the corrective action necessary to sustain project convergence on the end goals and objectives. Keeping stakeholders informed of the progress and status as well as any challenges to completing the project. Obtaining stakeholder concurrence for changes to the project plan, if a change is necessary.

15.15 PROJECT AUDITS

An important part of project evaluation can be done through the conduct of a project audit. Project audits provide the opportunity to assess how work is being managed. Periodic audits have to be planned. An audit should have as its purposes:

• Determining what is going right, and why

• Determining what is going wrong, and why

• Identifying forces and factors that have prevented or may prevent achievement of cost, schedule, and technical performance goals

• Evaluating the efficacy of existing project management strategy, including organizational support, policies, procedures, practices, techniques, guidelines, action plans, funding patterns, and human and nonhuman resource utilization

• Providing for an exchange of ideas, information, problems, solutions, and strategies with the project team members

A project audit should cover key functions, depending on the nature of the project, in both the technical and nontechnical areas, such as:

• Engineering

• Manufacturing

• Finance and accounting

• Contracts

• Purchasing

• Marketing

• Organization and management

• Quality

• Reliability

• Test and deployment

• Logistics

• Construction

How often should an audit be conducted, given that a thorough audit takes time and money? Generally, audits should be carried out at key points in the life cycle of a project, and at times in those phases of the life cycle that represent go/no-go trigger points, such as preliminary design, final design, first prototype, commitment to production, first use, warranty, and maintenance and service contracts.

An unplanned audit may be called for during the project life cycle if principal managers sense that the project is in trouble or is heading for trouble. If there is uncertainty concerning the project’s status, or if there has been a change in the strategic direction of the organization, an audit of the project may be in order. When a new project manager takes over a project, she or he should order an audit, both to become familiar with an unbiased view of the project and to come up to speed with the key issues and problems that are facing the project.

A project audit is a formal independent evaluation of the effectiveness with which the project is being managed. A typical audit evaluates the adequacy of the project management system being used, the effectiveness of project planning and implementation, and the adequacy of project guidelines, policies, and procedures. Its purpose is to provide an objective and impartial assessment of the manner in which the project is being managed and the results that are likely to be accomplished through the use of the project resources. The audit participants should ensure that adequate documentation is provided to the audit team and that suitable presentations are given to the team to acquaint them with the status of the project; they should participate in interviews with members of the audit team, and they should work with audit team to develop remedial plans for the full exploitation of the audit team’s recommendations. The principal responsibilities of the audit team include:

• Critical review of the project documentation.

• Interview of the project team and other project stakeholders to gain insight into their perceptions of the project affairs.

• Participation in enough of the project activities to gain an appreciation of what is going on regarding the project and an insight into the project problems and opportunities.

• Preparation and submission of a final audit report and the debriefing of the project stakeholders on the results of the audit.

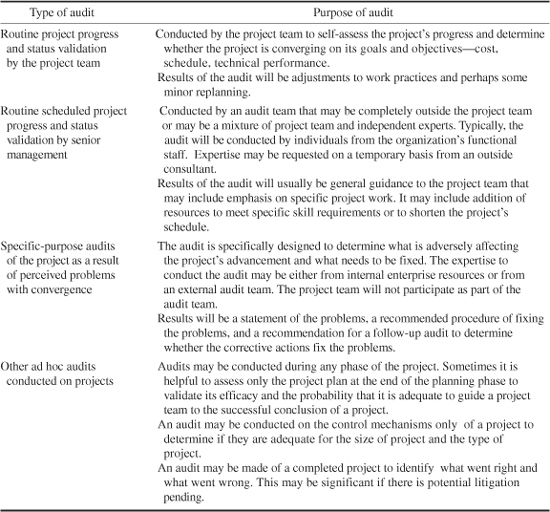

15.16 PROJECT EVALUATION

Project evaluations are performed either on a routine basis or for special reasons. The project team, for example, should routinely conduct assessments of their project to determine whether it is progressing within the scope as expressed in the project’s goals and objectives. Senior enterprise management may require that a project be evaluated for progress on a routine basis—such as during stages of project execution—to determine how the project is progressing and to build confidence that the project will meet its goals and objectives. Senior enterprise management or the customer may direct a project evaluation and review because of perceived problems or to validate the status of the project. These ad hoc reviews typically are triggered by major challenges to completing the project.

Major problems that have the potential for materially affecting the outcome of the project require unanticipated, immediate action to define the problems, identify corrective actions needed, and change the direction of the project. Special evaluations and reviews typically have limited scope objectives: Identify and fix problems that block the project from progressing as originally planned.

Historically, these special project reviews have had dramatic outcomes such as major replanning efforts, reduction of the scope of the project, and replacement of the project manager. It has been observed that new project managers assigned as a result of a failing project have greater authority and senior management support than previous project managers. Furthermore, the failing project will often have a higher priority for resources than before the project review.

Scheduled project evaluations have two primary purposes. First, an audit is conducted to determine how well the project is progressing toward satisfaction of its cost, schedule, and technical performance objectives and in what manner. Second, an audit is conducted to determine whether the project promises to contribute to the strategic management choice elements of the enterprise, primarily to the goals of the enterprise, as envisioned during the planning phase.

As indicated in Table 15.2, an audit may be conducted on a project for any number of reasons. Perhaps the only criterion for conducting an audit is that the benefits exceed the cost of the audit.

TABLE 15.2 Types and Purposes of Audits

The project team is best suited to maintain an ongoing evaluation of the cost, schedule, and technical performance goals of the project. Although the project team should maintain an ongoing audit of the project’s status, formal evaluation of the project’s progress should be done on a regular basis, probably at least monthly for medium- and large-size projects. The project sponsor (or owner) should be present, along with other select stakeholders, during this formal review. As often as needed, senior enterprise managers should be present at these formal reviews to gain insight into how well, and in what manner, the project is likely to make a contribution to the strategic objectives of the enterprise.

An ongoing overall assessment of a project by the project’s team is not the same as a regular project review. A project review is an event to examine the current status of the project’s progress in meeting its cost, schedule, and technical performance objectives. The project review should be held for the benefit of the project team, the sponsor(s), which includes the owners, and other interested and appropriate stakeholders. A project review should be held as often as needed so that the key stakeholders can determine how well the project is doing—and how likely it is that the project will contribute to the goals of those stakeholders.

A project office is the likely organizational unit to conduct the project review. The project office can prepare an inventory of topics that should be considered in the reviews; each stakeholder should be available to suggest topic areas that can be reviewed. The purpose of the formal project review is to determine if the project is likely to contribute to the “stake” that the stakeholders have regarding the project and to identify problems with the project that might adversely impact the stakeholders’ goals.

Each project reviewed should provide written summary information of the project’s status that can be disseminated to those attending the review. As a courtesy, the project team should have the privilege of looking at this summary information to determine its validity and reliability—and what corrective action, if any, should be carried out.

Formal project reviews constitute a major effort to evaluate a project’s status. A few summary considerations should be acceptable to those individuals who conduct a review—and those individuals for whom the review is carried out. The project plan should stipulate how often and under what considerations a project review should be carried out—and contain as a minimum the following strategies:

• A description of when, how, and what project review methodology and administrative processes will be carried out.

• Commitment of those organizational managers who use projects as building blocks in the design and implementation of choice elements in the strategic management of the enterprise.

• The propagation of an organizational culture that views project control in a positive way—both from the project’s standpoint and the strategic management context of the enterprise.

• Use of project performance standards as a guide to reviews—carried out in a professional manner.

• Project reviews done in the spirit of improving the management of the project as needed, and certainly not to find and place fault if there are problems in how the project is being carried out.

Those people who participate in, or will benefit from, project reviews should not forget that most project failures happen because basic project management principles and processes have been inadequately applied.

One large, and ultimately successful, project was evaluated using the following philosophy: The use of a postproject review can provide valuable information to be used in the management of future projects. In order to do such postproject reviews, several requirements must be met:

• A standard methodology and philosophy must exist as a template for managing projects in the enterprise.

• A project management review board, which will act as a sponsor, must be created, as well as a project management review team, which should be organized and used to carry out the review.

• The review must be carried out in the spirit of “lessons learned” and not as a subterfuge for finding fault.

• During the review, the project team is to be asked questions concerning how the project was managed during its entire life cycle. The planning phase of the project should be given particular scrutiny.

• The findings of the review process should be summarized in the spirit of the strengths and weaknesses with which the project was carried out.

• Particular attention should be given to the conditions—and restraints—under which the project team had to operate.

• The results of the postproject reviews are provided to existing project teams. Each time a team is formed for a new project, the existing database of “lessons learned” from previous projects should be reviewed by the new project team.

A project audit is another way to gain in-depth understanding of what is going on in a project—and in the management of that project. Project audits take time and money to do properly. Because of the cost in time and money, project audits are not often used. But, an audit can provide much value for ensuring that project controls are working and that stakeholders really understand what is going on in the project. What can a project audit do for you?

• Provide complete and objective information on the progress of the project and include the likely contributions that the project makes to the choice elements of the enterprise.

• Provide insight into the effectiveness and efficiency of the support that the enterprise functional elements and other organizational units are providing to the project.

• Ensure consistency across the enterprise on how projects are managed and measured in terms of quality, reliability, contribution of organizational choice elements, and other performance standards for the project and the enterprise.

• Provide for standards in following up on collective and preventive action.

• Identify areas in which a project’s management can be improved—and how such improvements can serve as valuable lessons learned for ongoing and future projects. Project audits can be general, in which the overall project is evaluated. In some cases a part of the project may need to be audited, such as technical assessment, financial prudence, systems support, customer satisfaction, planning or control systems adequacy, or probable contribution to the enterprise’s choice elements.

There are several steps to be carried out in the audit of a project. The following list is a general guide to this process:

• Selection and preparation of a team to carry out the audit.

• Selection or development of performance standards that will be used for comparison purposes during the audit.

• An initial meeting of the audit team and selected project stakeholders to be briefed—and to reach consensus on what will be audited and how the audit will be carried out.

• Collection of relevant information through questionnaires and interviews with appropriate stakeholders, study of project documentation, and briefings on the project’s progress regarding its cost, schedule, and technical performance objectives.

• Analysis of the differences between what the project should have accomplished vis-á-vis what has been done—expressed in the form of gap analysis.

• A closing meeting of project sponsors, project team, and other stakeholders to communicate the results of the audit.

• Feedback to appropriate senior enterprise managers, the project team, and other project stakeholders regarding development and delineation of appropriate strategies to correct any shortcomings of the project.

• Follow-up on recommended corrective actions for the audited project and implementation of preventive measures to avoid weaknesses in the enterprise’s project management methodology, policies, procedures, best practices, and techniques.

• Integration of audit results into an inventory of “lessons learned” for dissemination to existing project teams and future project teams.

The benefits of project audits, mindful of the costs, include the improvement of the enterprise culture for project management, opportunity for closed-loop corrective action, evidence that project monitoring, evaluation, and control are important, and the indoctrination of present and future project managers in the wisdom of exercising reasonable and prudent management of assigned projects. A key benefit is that the carrying out of such audits sends a clear message to the enterprise that projects are important in the management of this organization.

15.17 TO SUMMARIZE

Some of the major points that were expressed in this chapter include the following:

• Henri Fayol, often called the father of modern management, stated that control involves whether everything occurs in conformity with the plan adopted, the instructions issued, and the principles established.

• The control cycle presented in Fig. 15.1 is the key model to use in designing and executing control systems for an enterprise and for a project.

• A series of concepts and philosophies were suggested as essential elements for the assessment of project results.

• Performance standards are reflected in the project plan and are the key targets against which to judge project results.

• Performance observations take many forms, both informal and formal, and should be expanded as needed to garner feedback on project performance.

• When planned and actual performance is carried out, the comparison module of the control cycle is being used.

• Corrective action to modify in some manner the use of resources on the project has as its primary purpose the reallocation by some means of the resources committed to the project.

• Systems do not control people and the project team and other key stakeholders have an inherent responsibility to implement the monitoring, evaluation, and control functions on a project.

• In Table 15.1 some key questions regarding carrying out the monitoring, evaluation, and control functions on a project were suggested.

• A series of management function evaluation questions were suggested to provide additional importance to the monitoring of project progress and results.

• Project monitoring, evaluation, and control cannot be done without relevant and timely project information.

• A project should be evaluated at least during the key points in the project’s life cycle.

• A project review should be done at the work package level, the functional manager’s level, the project level, the general manager’s level, and the project owner’s level.

• Project audits can be carried out at any time during the project’s life cycle when the efficacy with which resources are being used on the project comes into question.

• A general paradigm for what to review during a project audit was suggested.

• The use of postproject reviews can provide valuable lessons on how to better manage future projects. It is important that a postproject review not be used to “find fault” in the management of a project.

• The control function should never be considered in the context of “command and control” or dominion or dominance. Rather, monitoring, evaluation, and control are the organized means used to determine progress in the project.

• Project success or failure is relative to the interests of the stakeholder.

• Projects may fail in the classic sense of not meeting cost, schedule, and technical performance criteria or not meeting the customers’ needs, but may provide benefits through by-products that far exceed the cost.

• Projects succeed most often when properly planned, implemented, and controlled while receiving senior management support.

• Project audits and evaluations identify opportunities for improvement.

15.18 ADDITIONAL SOURCES OF INFORMATION

The following additional sources of project management information may be used to complement this chapter’s topic material. This material complements and expands on various concepts, practices, and theory of project management as it relates to areas covered here.

• Edward W. Ionata, “Managing Environmental Regulatory Durations,” and Robert H. Kohrs and Gordon C. Weingarten, “Measuring Successful Technical Performance: A Cost/Schedule/Technical Control System,” in David I. Cleland, Karen M. Bursic, Richard J. Puerzer, and Alberto Y. Vlasek, Project Management Casebook, Project Management Institute (PMI). (Originally published in Proceedings, PMI Seminar/Symposium, San Diego, 1993, pp. 152–156; and Proceedings, PMI Seminar/Symposium, Montreal, Canada, 1986, pp. 158–164.)

• Al and Jackie DeLucia, Recipes for Project Success, Project Management Institute, 2001. This book offers 10 key tips for project success. The authors give tips on planning, running a project, and controlling the work through analogy to cooking. Basic project management information is provided for the newly appointed project manager, who needs a quick, simple explanation of techniques and principles. This book gives good tips on what to do and what issues to avoid that place the project at risk. The principles given are proven through experience and good, sound logic.

• James R. Snyder, “How to Monitor and Evaluate Projects”; Daniel P. Ono, “Project Evaluation at Lucent”; and Carl L. Pritchard, “Project Terminations: The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly,” Chaps. 25, 29, and 30 in David I. Cleland (ed.), Field Guide to Project Management, 2nd ed. (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley and Sons, 2004).

• Gregory T. Haugan, Project Planning and Scheduling (Vienna, VA: Management Concepts, 2001). This book addresses all aspects of project planning from considerations for strategic and operational planning with details that are required by the project team. It is a cohesive step-by-step approach to planning projects.

• Janette Simpson, “The Measure of Success,” Intelligent Enterprise, San Mateo, Calif., June 29, 2001, pp. 22–23. This article addresses the need for metrics in a project to be able to measure success. A project needs some agreed-upon method of determining whether a project is successful and metrics that stakeholders commit to. These metrics need to be in place prior to the start of a project and used to gauge the progress. Through these metrics, one can assess the project’s degree of success.

15.19 DISCUSSION QUESTIONS

1. List and briefly define the elements of the project control cycle. Why is control an important project management function?

2. What performance standards must be set in order to control a project? How can these standards be observed throughout the life of the project?

3. In what ways is corrective action carried out? What are some of the potential impacts of these corrective actions?

4. Discuss the personal nature of control. How can managers foster an environment that supports the control system?

5. Monitoring and evaluating are integral to control. Discuss what is meant by each. How do they relate? What kinds of questions must project team members ask in order to continually monitor and evaluate the project?

6. Discuss the importance of monitoring and evaluating with respect to all project stakeholders.

7. When should the project be monitored and evaluated? Discuss the ability to make changes over the project life cycle.

8. Who should be responsible for monitoring and evaluating projects? Where should monitoring and evaluating take place?

9. What is required in a project audit? What purposes do project audits serve?

10. List and discuss some of the factors that lead to success of a project.

11. List some of the by-product benefits of projects for an organization, whether they are successes or failures.

12. List the criteria that a customer might use to define success. List those criteria for failure.

15.20 USER CHECKLIST

1. Do project managers establish appropriate performance standards based on the project plan so that the control cycle can be effectively carried out? What performance standards are overlooked?

2. How is project performance observed in your organization? What comparisons are made to standards? What corrective actions are taken?

3. Is the cultural ambience of your organization supportive of the control systems? Why or why not?

4. What questions do project managers ask in order to monitor and evaluate project performance? Do managers consider the requirements of all project stakeholders in monitoring and evaluating project performance? Explain.

5. Are monitoring and evaluating done at the appropriate points in the project life cycle? Do project managers take advantage of the early opportunities to influence project success? Explain.

6. Are project monitoring and evaluating a part of the early project plans? Do evaluation policies and procedures exist? Are key managers committed to the evaluation strategy? Explain.

7. Are project audits performed on projects within your organization? Who is responsible for project audits? Are the audits effective? Why or why not?

8. What types of postproject reviews are carried out by your organization? How do these reviews contribute to the success of other ongoing projects?

9. What factors (with respect to project control) have contributed to the success of projects within your organization? Explain.

10. Does your organization have an evaluation system for projects after they are completed? Describe it.

11. How does your organization define a successful project? What objective criteria are used?

12. Who in your organization decides whether a project is a success or a failure?

15.21 PRINCIPLES OF PROJECT MANAGEMENT

1. Project success or failure are relative terms, defined by the project stakeholder and based on his or her interests.

2. Project audits are required to measure the degree of progress of projects.

3. Projects have by-products that benefit stakeholders in other ways than direct return on the projects.

4. Project controls measure progress and guide required for corrective actions to meet the project’s objectives.

5. Project control is exercised against the project plan and an organization’s project performance standards.

15.22 PROJECT MANAGEMENT SITUATION—ESTABLISHING A PROJECT CONTROL SYSTEM

An organization has been managing projects for several years through a group of project managers, specifically hired for their successes with this type of work. They have consistently performed well in other organizations, demonstrating an exceptional understanding of the technology and the project management discipline. They are excellent communicators and keep all parties informed of the progress of projects.

Recently, the company finance director stated that many of the projects were losing money. This was determined when the new accounting system was implemented and costs for projects were collected, collated, and analyzed. Nearly one-third of the projects were not performing well in the cost area. Only 18 percent of the projects were producing revenues that met the company’s fee structure.

A review of project documents and plans as well as discussions with some project participants revealed the following:

• There was no consistency in the project plans. Some were missing vital information and others were inconsistent with the company’s policies for project operations.

• Each project manager followed a different life-cycle model and methodology for similar projects. There was no single methodology being used for projects.

• Project managers relied on their experience, methodologies, and styles from their prior organizations.

• Project managers considered all projects to be successful if they met the cost, schedule, and technical performance objectives. Because cost data were not provided by the accounting department, it was assumed that projects were making money.

• No project audit had been conducted in at least 3 years and there were no procedures for conducting an audit. No trained people were available to conduct audits. The project managers were hired because they were “experts” in managing projects.

Senior management was in a quandary—experienced project managers were not providing the desired cost performance results and there may be other areas that were in need of fixing. Further, the company relied heavily on projects to generate most of its revenue. There was a need for some immediate action to move the company into a better cost performance position.

15.23 STUDENT/READER ASSIGNMENT

1. From the information given in the project management situation, what is the most likely problem and how would one fix it?

2. Why do highly qualified project managers use different methodologies in the same company? Is this a problem?

3. What are some of the reasons for lack of meeting cost performance (profit) goals? What can be done to improve the situation?

4. Does the company’s project control system work? What, if any, changes should be made?