Chapter 7

For better and for worse: effects

studies and beyond

Karl Erik Rosengren Ulla Johnsson Smaragdi

and Inga Sonesson

INTRODUCTION

Modern media and communication studies may be said to have started as a consequence of a moral panic (Cohen 1972/80; Roe 1985) about the effects of the new mass medium of film. At the initiative of the US Motion Picture Research Council, the so-called Payne Fund Studies were carried out in the late 1920s by a number of leading sociologists and psychologists including, for instance, Herbert Blumer, Philip Hauser and L.L. Thurstone (see Lowery and De Fleur 1983: 31 ff.). A couple of decades later, for similar but different reasons, comic magazines for children and adolescents triggered another moral panic. Again research into the effects of individual use made of mass media was carried out, this time by a psychiatrist who, incidentally, found an enthusiastic sympathizer in a Swedish professor of social medicine (Wertham 1954; Bejerot 1954; cf. Lowery and De Fleur 1983: 233 ff.).

Meanwhile, although somewhat less inclined to be seized by moral panics, leading members of the pioneering generation of communication scholars -for instance, Carl Hovland, Paul F. Lazarsfeld, and Wilbur Schramm — had also become much preoccupied by effects studies. About a decade after the introduction of television, the stage was set, then, for a couple of path-breaking, rather comprehensive effects studies in Europe and America (Himmelweit et al. 1958; Schramm et al. 1961), soon to be followed up by a number of studies more or less specifically focused on the media and violence problematics (for instance, Baker and Ball 1969; Comstock et al. 1978; Pearl et al. 1982; Surgeon General 1972). This tradition, of course, is still very much alive (see below).

Besides these broad developments, a number of other types of media effects — both positive and negative — were dealt with within the effects research tradition at large, the innumberable studies of which have been summarized and anthologized in several volumes such as Bradac (1989), Bryant and Zillmann (1986), Klapper (1960) and Schulz (1992). Hearold (1986) made a meta analysis of more than 1,000 positive and negative effects studies of television on social behaviour, finding that the average size for prosocial television contents on prosocial behaviour was far higher than that for antisocial television content on antisocial behaviour.

Parallel with the mainly effects-oriented studies, that other broad tradition of research on individual use of the media — uses and gratifications research, originally inaugurated by the group around Lazarsfeld and Merton at Columbia — continued to grow (see, for instance, Blumler and Katz 1974; Rosengren, Wenner and Palmgreen 1985; Swanson 1992). Increasingly often, the originally rather marked divide between effects and uses and gratifications tended to disappear in studies of individual media use.

The Media Panel Program tries to combine the two perspectives of effects and uses and gratifications research in a ‘Uses and Effects’ approach (Rosengren and Windahl 1989: 8 ff.; Windahl 1981). We also make a distinction between effects and consequences; the former being related to the type of content consumed, the latter, to the media use as such (Windahl 1981; cf. Cramond 1976). We try to relate our approach to the four aspects of media use listed in Chapter 4:

1 Amount of media use.

2 Type or genre of media content used and preferred.

3 Type of relation established with the content used.

4 Type of context of media use.

Within the MPP group, we are in a position to heed both short-term and long-term effects and consequences, since our combined cross-sectional/ longitudinal approach offers opportunities for studies ranging from the observation of immediate, cross-sectionally observed effects and consequences to that of effects and consequences which remain — or appear — only after several years.

While most effects studies have been concerned with what has been regarded as harmful effects (say, an increased tendency to violent behaviour), we are equally interested in positive and negative effects. Indeed, our uses and effects approach makes us realize that the good is sometimes the mother of the bad: long-term effects which from most reasonable perspectives must be considered harmful often have their origin in short-term positive effects more or less consciously sought for by the individual user of mass media (see below). For this reason also, then, the predominantly causal perspective of effects research must be combined with the predominantly finalistic perspective of the uses and gratifications research (see Rosengren and Windahl 1989: 211 ff.).

This chapter starts with a type of consequence not often mentioned in traditional effects studies: consequences of media use for future media use by the individuals themselves or by other family members (see the notion of stability analysed in Chapter 6). Viewing breeds viewing. We note that the idea of consequences of media use for future media use may be applied not only to amount of use, but also to the other three aspects of media use: type of content used and preferred, type of relation established with the content used, and type of context of media use.

Starting from a typology of television consequences developed within the MPP, we then turn to consequences and effects of media use on other phenomena: characteristics and qualities of individuals as well as more or less stable patterns of actions and activities stemming from media use as such and from media use of special types of content. In so doing, we concentrate, of course, on new MPP results not otherwise presented in this volume. A number of other effects and consequences will be dealt with in the following two chapters in this section of the book. In the next section of the book, yet a different perspective on the relationship between media use and other activities will dominate.

CONSEQUENCES OF MEDIA USE FOR MEDIA USE

In Chapters 5 and 6, by Pingree and Hawkins, and Johnsson-Smaragdi, respectively, we saw that the use of some media tends to correlate, often positively, sometimes negatively. Although patterns of such correlations may change during and after periods of structural change, they seem to be stable enough to merit further study. There are at least two different ways of interpreting such relationships.

Especially in cross-sectional studies, perhaps, co-variation between amount of use of different media may be taken to indicate a pattern of living supposedly characteristic for this or that type of society, this or that type of segment within the population, this or that group of individuals sharing some basic values or attitudes. By and large, that is the perspective applied in Chapter 5 (see also the notions of forms of life, ways of life, and lifestyle as discussed in Chapter 1 and Chapters 10–12). When the correlations are longitudinal, however, it seems to be more natural to regard them as measures of stability, as in the previous chapter by Ulla Johnsson-Smaragdi. And stripped of the influence of basic positional variables such as gender and social class, these longitudinal relationships actually bring to mind the notion of causality. Amount of media use at one point in time may be regarded as partly caused by amount of media use at a previous point of time (see Chapter 6, p. 112). Obviously, the same type of argument may be applied also to aspects of media use other than amount of use, for instance, relations established with the media content used.

There are a number of different types of media relation which have been discussed in the literature. The two relations which have been the most preferred by media scholars are probably identification and para-social relation (PSI). The latter type of media relation, originally inaugurated by Horton and Wohl (1956), explicated by Rosengren and Windahl (1972) and recently reviewed by Hippel (1992), has also been a focus of interest in the Media Panel Program. Briefly, it could be characterized as a quasi-interaction between viewer and some persona on the screen. Identification has also been given much attention within the MPP. Identification may be short term or long term, and we have been most interested in long-term identification: a relation in which the viewer — often for relatively long periods of time after the viewing — tends to identify, more or less superficially or deeply, with a persona on the screen, say, the hero or heroine of this or that series or serial. A combined index of PSI, short-term and long-term identification called ‘TV Relation’ was used in most MPP waves of data collection (see Rosengren et al. 1976; Rosengren and Windahl 1989: 38 ff.).

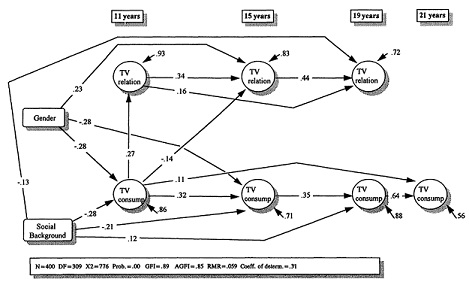

Figure 7.1 presents a LISREL model of the causal relations between amount of TV consumption and TV relations during childhood, adolescence and early adulthood. Before turning to these causal relations, however, we note what we have had opportunity to note several times before, namely, that gender and social background are powerful determinants of media use.

Girls watch less TV than boys, but they are more inclined to establish TV relations. Upper-class youngsters watch less TV than do working-class youngsters. But in early adulthood, at the same time as they are less inclined to enter into TV relations, they seem to watch somewhat more (perhaps because as students they lack the money necessary for frequent disco visits and such like). In general, TV relations are less influenced by background variables than is TV consumption, possibly because they may be related to some personality variable or other (see Rosengren and Windahl 1977).

The intricacies of such causal relationships between aspects of media use and background variables are interesting as such, but in this connection we are more interested in discussing the causal relationships within aspects of media use itself. It is striking to note how — even after control for the two powerful background variables of gender and social class — the so-called stability coefficients for TV consumption are quite strong. What is really striking, however, is that this applies not only to amount of viewing but also to that much more subtle and presumably fleeting variable of TV relations -indeed, the coefficients for the relations are even stronger than those pertaining to the amount of viewing. (The total effect of viewing upon viewing may be calculated as the sum of direct and indirects of early viewing on later viewing. For such total effects, see corresponding figures in Chapter 6.) In causal terms this means that not only does viewing breed viewing; relationships also breed relationships.

What we see is the strong power of media habits. Once a TV fan, chances are you will remain one — even after having passed that period of turmoil called adolescence. Expressed in stronger terms, what we see is not only the development and conservation of a habit, but also a process of habituation, sometimes resulting in mild forms of media dependency, ‘addiction’. This type of dependency is described, for instance, by McQuail and Windahl (1981); see also Rubin and Windahl (1986). (Similar phenomena may be observed for most media, as well as between different media. For examples

Figure 7.1 LISREL model of TV consumption and TV relations between ages 11 and 21 — structural part. Cohorts M69 and V69 (only statistically significant paths are presented)

of positive and negative relationships between, say, early and late book reading and use of other media, see Chapter 6.)

The consequences of heavy TV viewing among youngsters are often the concern of parents, teachers and other citizens, sometimes for good reasons. One good reason for such concern, we have just seen, may well be the fact that viewing often turns into a habit, so that it could be said that viewing itself causes and ensures continued viewing. On the assumptions that viewing may reduce other activities, and/or that effects and consequences of viewing are sometimes harmful, this is a result of childhood viewing which should be, and often is, a matter of some concern.

Actually, the influence of amount of viewing on amount of viewing is not limited to one's own viewing. In Chapter 6, Ulla Johnsson-Smaragdi showed that parental viewing is a strong causal factor behind children's viewing — even after control for background variables (see also Johnsson-Smaragdi 1992). Interestingly, she also showed that children's viewing may exert an influence on parental viewing, especially in mid-adolescence when (during a public-service regime, at least) many youngsters leave mainstream television for music which reaches them through other media (see Chapter 4). In cases where the youngsters remain seated before the screen, however, so do their parents, it seems (cf. Johnsson-Smaragdi 1992). For both parties involved in the process, the ‘context’ aspect of viewing is at play (see above): joint viewing by parents and children alike.

This observation is strengthened by the fact noted by Rosengren and Windahl (1989: 83 ff.) that Parents' TV viewing diminishes with the age of their children. This is the result of a form of dependency other than the mild form of addiction described above: structurally rather than individually generated dependency — a type to be understood in terms of dependency theory as developed by Ball-Rokeach and her associates (Ball-Rokeach and De Fleur 1976; Ball-Rokeach 1985, cf. Ball-Rokeach 1988). Small children make parents stay at home, make them dependent on home-bound pleasures — television, for instance. As the child grows older, this dependency is gradually reduced, and consequently children and parents alike leave television for the real world. It remains to be seen, however, whether these tendencies will survive the changes in media structure which have already taken place but which may not yet have reached their end.

It should be added, finally, that the influence of viewing on viewing is not limited to the three aspects discussed so far: amount of viewing, relations established with TV content, and context of viewing. Also type of content preferred and consumed at one time influences type of content consumed at a later point in time. In an attempt at untangling the longitudinal relationships between television content preferences in childhood and early adulthood, Dalquist (1992) followed amount of television viewing and content preferences among cohorts V69 and M69 from the age of 11 (grade 5) to age 21, including data from five data collection waves and both panels in a

Figure 7.2 Long-term stability in media preferences (beta coefficients) (Source: Dalquist 1992)

number of sequential MCA analyses. As it turned out, a relatively clear-cut pattern of preferences was established fairly early: sports, contests and competitions stood out as a special interest already at age 12, an interest which persisted into early adulthood and had next to no relations with other preferences and interests.

Three other groups of preferences articulated already at the age of 12 and remaining until the age of 16 were directed towards fiction, youth programmes and informational programmes, respectively. At the age of 19, the young adults reshuffled these three groups into two groups of preferences: one consisting of entertainment programmes, action fiction and comedy fiction; another, of informational programmes and high culture programmes. After control for gender, social class, town of living and amount of viewing, the stability (beta) coefficients for the various preferences as measured in two contingent waves of data collection varied between some. 20 and some.60, depending on the temporal distance between the waves and the type of preference (sport showing the highest coefficients).

In a final attempt to assess also long-term stability in type of TV content preferred, Dalquist (1992) took a look at the long-term stability of preferences for the following programmes:

a) Sports, contests and competitions.

b) Fiction.

c) Informational.

The preferences were measured in grade 5 (age 12) and at age 21, again within the collapsed cohorts M69 and V69. The results obtained are shown in Figure 7.2. As it turned out, the beta coefficients — again after control for gender, social class, town and TV viewing — were significant and quite substantial:.15 and.19 for preferences for informational programmes and fiction, respectively, and.43 for sports programmes. Given the many variables controlled for, as well as the nine years’ interval betweeen the two waves of data collection, the coefficients are quite impressive, especially that for sports. What they show is that the basic foundations for television content preferences are laid at an early age, and that they are quite stable.

In summary, then, after control for a number of basic background variables, and in a long-term perspective, media use, having once been initiated, breeds media use. As far as TV is concerned, this seems so for all four aspects of media use: amount, content preferences, relations established with content used, and context of media use. This fact should not be forgotten when in the next section we turn to a discussion, not about consequences of media use for media use, but about effects and consequences of media use on other, and perhaps more important, activities.

ACTIVITIES AND CHARACTERISTICS FOLLOWING TV USE

In an attempt to clarify the relationships between TV use and other activities, Rosengren and Windahl (1989:179 ff.) created a three-dimensional typology providing seven different types of such relationships (since two of the eight theoretically possible types coincide):

1 Supplement: other activities stimulate TV use.

2 Prevention: other activities reduce TV use.

3 Substitute: lack of other activities calls for TV use.

4 Passivity: both TV use and other activities low.

5 Activation: high TV use stimulates other activities.

6 Leeway: low TV use leaves room for other activities.

7 Displacement: high TV use reduces other activities.

In terms of this typology, we then made an overview of results gained in a number of previous MPP studies — primarily by Sonesson (1979, 1986, 1989) and Johnsson-Smaragdi (1983,1986) - of the relationship between television viewing and other activities, including both parental viewing and children's viewing, as well as parental and children's activities. Contrary to some previous results we were able to conclude that

For parents and children alike, from preschool to grade 9, over various aspects of TV use and social interaction, we have found that TV does not reduce interaction. If anything, it does the opposite. Children high on TV are socially better integrated and more active. In preschool they are more apt to have a close friend. In grade 5, they interact more with parents and peers, and in grade 9 those who interact more with their parents also watch more TV. Only when it comes to organized leisure activities (sports, hobbies, etc.) did we find negative relationships. But here the influence ran from activities to TV viewing. A high amount of organized leisure activities reduced TV (prevention), a low amount of organized activities may have admitted — even called for — much TV (substitute). TV as substitute was found also for the parents. But TV did not reduce or admit the organized activities of the children (no displacement or leeway effects). (Rosengren and Windahl 1989: 188 f.)

We then proceeded to conclude that while these results were in disagreement with early American results, they agreed with some relatively recent results obtained in Europe and other regions outside the USA, arguing that the early US results referred to a period when TV was something relatively new and extraordinary, while our results referred to a period in which TV was a phenomenon well integrated in everybody's daily life. The 1989 results have received further support in later MPP studies, for instance, by Sonesson (1990). The analyses undertaken by Ulla Johnsson-Smaragdi and Annelis Jönsson in Chapter 8 show that, for girls, at least, a high amount of TV viewing in grade 5 resulted in increased interaction in grade 9. In retrospect one realizes, though, that present-day changes of the media structure may well change all this. (Whether that is so still remains to be seen, of course.)

What was clear already in the late 1970s and early 1980s, was that while TV viewing had hardly any passivating consequences at the time, it certainly was activating in more than one sense. Not only did it increase interaction with friends and parents; there are also clear signs that it increased other, less positive activities and characteristics.

The subject area most persistently pursued by mass communications studies with an effects/consequences perspective no doubt is the relationship between viewing, aggressiveness and violent behaviour (see the introductory section of this chapter). This specific subject has been given considerable attention within the MPP since its start in the mid-1970s (see Rosengren and Windahl 1989: 215 ff.). A series of studies undertaken on the M69 cohort actually focused specifically on this problem (Sonesson 1979, 1986, 1989, 1990), producing a wealth of detailed results which for space reasons cannot be rendered in any detail in this chapter. The main outcome of the studies is clear enough, however.

In her studies in the area Sonesson (1979, 1986, 1989) consistently applied a combined uses and effects perspective. Individual media use not only has its effects and consequences, but also its reasons and causes. In combination,

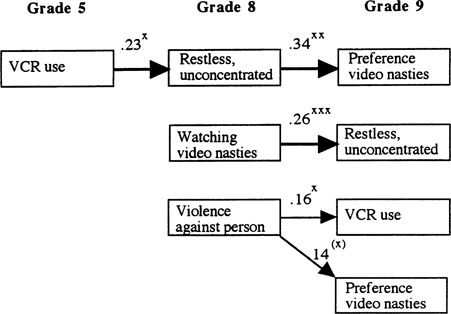

Figure 7.3 Chains of effects and consequences of TV and VCR use among boys in panel M69 (beta coeffinients)

the two processes proceeding and following media use may result in long chains of finality/causality and effects/consequences: spirals of interaction between individuals and their media environment stretching over decades. In Sonesson (1989) a number of such chains are presented, covering the period from pre-school (age 6) to grade 9 (the last year of the compulsory school system, age 15). They are summarized in an impressive series of consecutive MCA analyses of the relationship between mass media use and tendencies towards aggressiveness, restlessness and/or anxiety. Here is a condensed summary of these results, differentiated for boys and girls.

Figure 7.4 Chains of effects and consequences of TV and VCR use among girls in panel M69 (beta coefficients)

The amount of boys' TV viewing in pre-school affected tendencies to (relatively mild) aggressiveness in grade 5 (beta. 28). In its turn, this aggressiveness led to high viewing of video violence and horror content in grade 8 (beta. 26), which in its turn led to restlessness and lack of concentration (beta. 24) in grade 9; VCR viewing in grade 8 (including, of course, the video nasties) led to (relatively harsh) aggressiveness against people in grade 9 (beta. 21) - all coefficients after control for social background and previous aggressiveness, restlessness, lack of concentration, etc. (gender being controlled for by homogenization). For girls a similar chain of uses and effects was found, although with other types of effect. Here the amount of VCR viewing in grade 5 led to restlessness, lack of concentration and attention in grade 8 (beta. 23), which in its turn led to high preferences for violence and horror video content in grade 9 (beta.34) - again after extensive controls for relevant variables (social background, previous lack of concentration, previous media use and media preferences, etc.).

Disregarding for the moment the specifics and the details of these studies, what these and similar MPP results convincingly show is that media use has effects and consequences for children which may stretch over years, probably decades. We also see how such effects and consequences come about in spiralling uses-and-effects chains of interaction between individual characteristics (aggressiveness, restlessness, etc.) and media use (media preferences, amount of viewing, type of content viewed), in a way which is in agreement with a number of other studies in the area, and especially, perhaps, with the so-called reciprocal cognitive models summarized, for instance, in Linz and Donnerstein (1989) and implemented, for instance, in a large, relatively recent international comparative study (see Eron and Huesmann 1987; Huesmann and Eron 1986). They are not in agreement, however, with results arrived at within the same comparative study as interpreted by Wiegman et al. (1992). Nor are they in agreement with a recent meta analysis of gender differences in the effects of television violence (Paik 1992), which surprisingly found no or only small gender differences. There will always be deviant results, of course. Sometimes such results will result in new and unexpected insights, sometimes they may be explained in terms of specific circumstances (as cleverly done, for instance, by Turner et al. (1986) with respect to the otherwise deviant results presented by Milawsky et al. (1982)).

The debate goes on. It may well be that future combinations of uses-and-effects models and reciprocal cognitive models will be able to solve some of the differences found in the literature. The fact that aggressive commercials have been shown to enhance and facilitate aggression (see, for instance, Caprara et al. 1987) makes it mandatory to continue and replicate longitudinal studies, especially in countries which have recently experienced a restructuring of the media scene making such commercials a standard part of many young people's media fare. Also, while most results suggest rather weak effects in terms of proportion of explained variance, those effects are virtually globally endemic, and even a small portion of all violence in all countries must represent immense, almost staggering amounts of violence. In addition, Rosenthal (1986) convincingly showed that even seemingly modest amounts of explained variance may represent considerable amounts of actual reduction or increase of this or that type of behaviour.

Regarded in this perspective, it will be an important and fascinating task of future research within the MPP to follow up the spiralling chains presented above from grade 9 and onwards, a task which is quite feasible and which, as a matter of fact, has already been approached (Johnsson-Smaragdi and Jonsson, forthcoming). Preferably, such studies should be combined with similar studies of related subject areas, such as, for instance, school achieve ments and occupational plans and choices, an area which has also already been given considerable attention within the research programme.

Using the PLS approach (see Jöreskog and Wold 1982; for a short comparison of the PLS and LISREL approaches, see also Rosengren and Windahl 1989: 263 ff.), Jönsson (1985, 1986) showed that under positive and negative circumstances heavy viewing may have positive and negative effects on children's school marks — circumstances being defined as family background, context of viewing, type of content viewed and preferred. Under favourable circumstances — having parents with a critical view towards TV, viewing together with parents, viewing programmes created for children and adolescents etc. - TV viewing in pre-school and early school years showed up in better school marks in grade 6 (age 12), while opposite conditions had opposite effects and consequences (see also Rosengren and Windahl 1989: 221 ff.). In LISREL analyses carried out separately for boys and girls of the V65 cohort, on the other hand, Flodin (1986) found only a weak influence of amount of TV viewing in grade 5 on school marks in grade 6, and no influence on occupational expectations in grade 9 of viewing in grades 5, 7 and 9 (Flodin 1986; cf. Rosengren and Windahl 1989: 236 ff.); related results will also be presented in Chapter 8. We thus have results which point to no effects of TV viewing on school results and occupational plans, and results which suggest such effects.

Jönsson (1985, 1986) used a different statistical approach in her analyses than did Flodin (1986) and Johnsson-Smaragdi and Jönsson in Chapter 8, but common to the two statistical packages, PLS and LISREL, is that they very efficiently control for all relevant variables included in the analysis, so that the unique influence of one variable upon another stands out clearly. The main reason for the difference between the results presented by them, therefore, probably is a different one: the fact that Jonsson not only heeded amount of viewing but included also contextual background factors to viewing, and — at least equally important — that she was able to include also type of content viewed. Hers was a mixed consequence/effects model, then, presumably stronger than the pure consequence model used by Flodin. Also, Jönsson's main result — that, depending upon the circumstances, effects of TV viewing on scholastic achievements may be positive or negative — agrees with, provides comparative corroboration of, and adds new knowledge to the main message of an overview of the area published at about the same time (Ball et al. 1986). It also agrees with a rather different perspective quickly touched upon in the second section of this chapter: a lifestyle perspective, which actually brings us beyond the effects perspective in the strict sense of the word.

BEYOND THE EFFECTS PERSPECTIVE

We noted above that correlations between the use of different media may be interpreted either in causal terms (so that the use of one medium supposedly leads to the use of another) or as expressing a pattern of living (so that use of different media is taken to express the way the individual has come to lead his/her life). The choice between the two perspectives is often related to the time perspective applied, so that cross-sectional studies invite the pattern perspective; longitudinal ones, the causal perspective. But just as in cross-sectional studies a causal perspective may be applied, it is quite possible, of course — although not very common, perhaps — to apply a pattern perspective to longitudinal data. In so doing, we would be able to see how the emergence of patterns of media use interacts over time with the emergence of other patterns of actions and characteristics, be they structurally, positionally or individually determined. In such a perspective a narrowly defined effects perspective breaks down.

An attempt at such a longitudinal, pattern-oriented design was made by Jarlbro and Dalquist (1991), who comparing social background at age 11 and educational status at age 21 for members of cohorts M69 and V69 classified the young adults as either‧Climbers’, ‘Droppers’, ‘Stable Working Class’ or ‘Stable Middle Class’. The media use among members of the four categories was then studied by means of a number of MCA analyses, controlling for gender, place of living and, when applicable, other relevant variables. Here are some results obtained, complementing in an interesting way more traditional analyses showing that working-class children watch more TV etc:

• Working-class children with low TV viewing at the age of 12 tended to be climbers at the age of 21 (beta:.32).

• Middle-class children with high TV viewing at the age of 12 tended to be droppers at the age of 21 (beta:.41).

• Droppers tended to have high TV viewing at the age of 21 (beta. 31), to often visit restaurants (beta. 22) and to be heavy VCR users (.36).

• Climbers and Stable Middle-Class young adults tended often to visit libraries (beta. 28 and. 36, respectively).

These results should only be regarded as tentative, of course, but they are suggestive indeed, and what they suggest is a quite subtle pattern of anticipatory socialization (Merton 1963: 265 ff.) rather than the strictly causal processes relevant to an effects perspective (see also Chapter 9 by Keith Roe, where a similar perspective is theoretically elaborated and empirically illustrated). It is hardly high or low TV viewing per se which sends youngsters up or down the social ladder. What we see, rather, is youngsters starting to choose their future, more or less consciously and intentionally, more or less compelled by strong but often hidden forces within themselves and outside of them, in their surroundings. Starting to form their lives, they sometimes make a virtue out of necessity (choosing and liking whatever under the circumstances seems to be the thing to do, given their ambition or lack of ambition), sometimes they seem very consciously, very deliberately to choose patterns of living corresponding to their inner cravings and inherent capacities (see Chapters 1 and 13). What we see, then, is specific patterns of values, attitudes and actions emerging out of a common form of life, patterns which are partly determined by social position (ways of life), partly by individual choice (lifestyles).

Analyses of this and similar types transcend both effects studies and uses and gratification studies, but they are quite consistent and compatible with a uses and effects approach as applied within a lifestyle perspective, and they cast an intriguing light on the discussions about socialization, agency and structure referred to in Chapter 1. With or without the intentions of the individual actors, different ways of using mass media — whether consciously chosen by the actors or not — contribute to the shaping of young people's present and future life. Young people often use mass media to express their basic values, their beliefs and opinions, their tastes and whims, and in so doing they help society to fulfil the more or less subtle sorting procedures which its agents of socialization — in this case, primarily, family, school, mass media — have been applying for as long as the young people have been alive. It almost looks as if the young people themselves choose a pattern of media use which later on affects them in a way which to the outsider may sometimes seem tragic and sometimes cynical, sometimes very conventional and sometimes quite unexpected.

In the next two chapters of this part of the book, and in the three chapters in Part IV, the perspective just outlined will be further detailed, extended and developed.

REFERENCES

Baker, R. and Ball, S.J. (eds) (1969) Violence and the Media, Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office.

Ball, S., Palmer, P. and Milward, E. (1986) ‘Television and its educational impact: A reconsideration’, in J.Bryant and D.Zillman (eds) Perspectives on Media Effects, Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Ball-Rokeach, S.J. (1985) ‘The origins of individual media systems dependency: A sociological framework’, Communication Research 12: 485–510.

—— (1988) ‘Media systems and mass communication’, in E.F.Borgatta and K.S.Cook (eds) The Future of Sociology, Newbury Park, Calif.: Sage.

Ball-Rokeach, S. and De Fleur, M.L. (1976) ‘A dependency model of mass media effects’, Communication Research 3: 3–21.

Bejerot, N. (1954) Barn, serier, samhalle, Stockholm: Folket i Bild.

Blumler, J.G. and Katz, E. (eds) (1974) The Uses of Mass Communications: Current Perspectives on Gratifications Research, Beverly Hills, Calif.: Sage.

Bradac, J.J. (ed.) (1989) Message Effects in Communication Science, Newbury Park, Calif.: Sage

Bryant, J. and Zillmann, D. (eds) (1986) Perspectives on Media Effects, Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Caprara, G.V., D'Imperio,G., Gentilomo, A., Mammucari, A., Renzi, P. and Travaglia, G. (1987) ‘The intrusive commercial: Influence of aggressive TV commercials on aggression’, European Journal of Social Psychology 17: 23–31.

Cohen, S. (1972/80) Folk Devils and Moral Panics (2nd edn), Oxford: Martin Robertson.

Comstock, G., Chaffee, S., Katzman, N., McCombs, M. and Roberts, D. (1978) Television and Human Behavior, New York: Columbia University Press.

Cramond, J. (1976) ‘The introduction of television and its effects upon children's daily lives’, in R.Brown (ed.) Children and Television, London: Collier-Macmillan.

Dalquist, U. (1992) ‘Om ungdomars val av TV-program. En longitudinell studie’, Lund Research Papers in Media and Communication Studies 2, Lund: Department of Sociology, University of Lund.

Eron, L.D. and Huesmann, L.R. (1987) ‘Television as a source of maltreatment of children’, School Psychology Review 16 (2): 195–202.

Flodin, B. (1986) TV och yrkesförväntan. En longitudinell studie av ungdomars yrkessocialisation (with a summary in English), Lund: Studentlitteratur.

Hearold, S. (1986) ‘A synthesis of 1043 effects of televison on social behavior’, in G.Comstock (ed.) Public Communication and Behavior, vol. 1, Orlando, Fla.: Academic Press.

Himmelweit.H., Oppenheim, A.P. and Vince, P. (1958) Television and the Child, London: Oxford University Press.

Hippel, K. (1992) ‘Parasoziale Interaktion. Bericht und Bibliographic’, Montage/AV 1(1): 135–150.

Horton, D. and Wohl, R.R. (1956) ‘cation and para-social interaction’, Psychiatry 19: 215–229.

Huesmann, L.R. and Eron, L.D. (eds) (1986) Television and the Aggressive Child: A Cross-national Comparison, Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Jarlbro.G. and Dalquist, U. (1991) ‘Mot alia odds. En longitudinell studie av ungdomars sociala mobilitet’, Lund Research Papers in the Sociology of Communication 30, Lund: Department of Sociology, University of Lund.

Jensen, K.B. and Rosengren, K.E. (1990) ‘Five traditions in search of the audience’, European Journal of Communication 5: 207–238.

Johnsson-Smaragdi, U. (1983) TV Use and Social Interaction in Adolescence. A Longitudinal Study, Stockholm: Almqvist & Wiksell International.

—— (1986) ‘Familjen, kamraterna och TV-tittandet’, in K.E.Rosengren (ed.) Pagott och ont: Barn och ungdom, TV och video, Stockholm: Allmanna barnhuset.

(1992) ‘Learning to watch television: Longitudinal LISREL models replicated’, Lund Research Papers in Media and Communication Studies 5, Lund: Department of sociology, University of Lund.

Johnsson-Smaragdi, U. and Jönsson, A. (forthcoming) ‘TV viewing and the social character — a long term perspective’, Lund Research Papers in Media and Communication Studies, Lund: Department of Sociology, University of Lund.

Jönsson, A. (1985) TV — ett hot eller en resurs. En longitudinell studie av relationen mellan skola och TV (with a summary in English), Lund: Gleerups.

——(1986) ‘TV: a threat or a complement to school?’, Journal of Educational Television 12(1): 29–38.

Joreskog,K.G. and Sörbom, D. (1988) LISREL 7. A Guide to the Program and Applications (2nd edn), Chicago: SPSS Publications.

Jöreskog, K.G. and Wold, H. (eds) (1982) Systems under Indirect Observation: Causality, Structure, Prediction, Amsterdam: North Holland.

Klapper, J. (1960) The Effects of Mass Communication, New York: Free Press.

Korzenny, F. and Ting-Toomey, S. (eds) 1992 Mass Media Effects Across Cultures,Newbury Park, Calif.: Sage.

Linz, D.G. and Donnerstein, E. (1989) ‘The effects of violent messages in the mass media’, in J.J.Bradac (ed.) Message Effects in Communication Science, Newbury Park, Calif.: Sage.

Lowery, S. and De Fleur, M.L. (1983) Milestones in Mass Communication Research, New York: Longman.

McQuail, D. and Windahl, S. (1981) Communication Models for the Study of Mass Communications, London: Longman.

Merton, R.K. (1963) Social Theory and Social Structure, rev. and enlarged edn Glencoe, 111.: Free Press.

Milawsky, J.R., Kessler, R.C., Stipp, H.H. and Rubens, W.S. (1982) Television and Aggression: A Panel Study, New York: Academic Press.

Paik, H. (1992) ‘Gender and the effects of television violence: A meta analysis’ (Paper presented to the AEJMC convention, Montreal, August 1992).

Pearl, D., Bouthilet, L. and Lazar, J. (eds) (1982) Television and Behavior. Ten Years of Scientific Progress and Implications for the Eighties, Washington, DC: Government Printing Office.

Roe, K. (1985) ‘The Swedish moral panic over video 1980–1984’, Nordicom Review 1:20–25.

Rosengren, K.E. (ed.) (1992) ‘Special issue on audience research’, Poetics 21 (4).

Rosengren, K.E., Wenner, L.A. and Palmgreen, P. (eds) (1985) Media Gratifications Research: Current Perspectives. Beverly Hills, Calif.: Sage.

Rosengren, K.E. and Windahl, S. (1972) ‘Mass media consumption as a functional alternative’, in D.McQuail (ed.) Sociology of Mass Communications, Harmonds- worth: Penguin.

Rosengren, K.E. and Windahl, S. (1977) ‘ass media use: causes and effects’, Communications 3: 337–351.

Rosengren, K.E, and Windahl.S. (1989) Media Matter. TV Use in Childhood and Adolescence, Norwood, NJ: Ablex.

Rosengren, K.E., Windahl, S., Håkansson, P.A. and Johnsson-Smaragdi, U. (1976)‘Adolescents’ TV relations: ‘Three scales’, Communication Research 3: 347–366.

Rosenthal, R. (1986) Media violence, antisocial behavior, and the social consequences of small effects’, Journal of Social Issues 42 (3): 141–154.

Rubin, A.M. and Windahl, S. (1986) ‘The uses and dependency model of mass communication’, Critical Studies in Mass Communication 3: 184–199.

Schramm, V., Lyle, J. and Parker, E.B. (1961) Television in the Lives of our Children, Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Schulz, W. (ed.) (1992) Medienwirkungen. Einflüsse von Presse, Radio und Fernsehen auf Individuum und Gesellschaft, Weinheim, Germany: VCH Verlagsgesellschaft.

Sonesson, I. (1979) Förskolebarn och TV. Malmo: Esselte Studium.

——(1986) ‘TV, aggressivitet och angslan’, in K.E.Rosengren (ed.) />På gott och ont: Barn och ungdom, TV och video, Stockholm: Allmänna barnhuset.

——(1989) Vemfostrar våra barn — videon eller vi?, Stockholm: Esselte Studium.

——(1990) ‘Barn i satellitåldern’, in U.Carlsson (ed.) Medier Människor Samhälle, Goteborg: NORDICOM.

Surgeon General (1972) Television and Growing Up. The Impact of Televised Violence, Washington, DC: Government Printing Office.

Swanson, D.L. (1992) ‘Understanding audiences: Continuing contributions of gratifications research’, Poetics 21: 305–328.

Turner, C.W., Hesse, B.W., and Peterson-Lewis, S. (1986) ‘Naturalistic studies of the long-term effects of television violence’, Journal of Social Issues 42 (3): 51–73.

Wertham, F. (1954) Seduction of the Innocent, New York: Rinehart.

Wiegman, O., Kuttschreuter, M. and Baarda, B. (1992) ‘A longitudinal study of the effects of television viewing on aggressive and prosocial behaviours’, British Journal of Social Psychology 31: 147–164.

Windahl, S. (1981) ‘Uses and gratifications at the crossroads’, in G.C.Wilhoit and H.de Bock (eds) Mass Communication Review Yearbook 2.