Chapter 10

Values, lifestyles and family communication

Fredrik Miegel

LIFESTYLE, IDENTITY AND VALUE

The empirical study of youth culture and young people's lifestyles is by no means an easy task. Depending on the purpose of the study, it can be conducted from quite different theoretical and methodological points of view. In this chapter I shall apply what might be called a value perspective. This is not a very original perspective, since several theories in the field combine lifestyle theory with a more or less developed value theory (see, for instance, Mitchell 1983; Kamler 1984). The reason for this is that behind most of our actions and attitudes lie a number of values, and since lifestyles are almost always empirically conceptualized and identified in terms of (patterns of) attitudes and/or actions, the value concept is obviously of central importance in this respect.

The values embraced by an individual also form a fundamental component of that individual's identity, and the identity is crucial for which lifestyle the individual will develop. This confronts us with two obvious difficulties:

1 Theoretically, we must define what we mean by the terms ‘value’, ‘identity’, and ‘lifestyle’, and there is no single and commonly agreed upon definition of any of these terms.

2 Empirically, we must be able to construct relevant methods to make each of these three phenomena empirically accessible.

I cannot, of course, offer any final solutions to these problems here, but only give a brief summary of the discussions carried out in Johansson and Miegel's Do The Right Thing (1992), where each of these questions is dealt with rather thoroughly (see also Lööv and Miegel 1989, 1991; Miegel 1990; Miegel and Dalquist 1991).

LIFESTYLE

One can distinguish three different but interrelated levels at which it is possible to study aspects of living, in a way relevant to a discussion of lifestyle: a structural, a positional, and an individual level (Johansson and Miegel 1992: 22ff; Lööv and Miegel 1989; cf. Heller 1970/1984; Thunberg et al. 1981: 61). The distinction clearly resembles that made by Habermas in volume two of The Theory of Communicative Action (1987). Habermas distinguishes between three structural components of the lifeworld, namely culture, society and personality. To each of these components he connects a reproduction process: cultural reproduction, social integration and socialization respectively (Habermas 1987: 135–148).

On the structural level one can examine differences and similarities between various countries, societies and cultures, but also differences evolving over time within one and the same society. We may refer to configurations primarily reflecting differences in societal structure as Forms of Life. In short, these configurations can be said to represent different forms of society and its culture.

The positional level concerns differences and similarities in relevant aspects of living between large categories, classes, strata or groups situated at different positions within a social structure. Configurations of this kind, primarily determined by the position held in a given social structure, we term Ways of Living.

On the individual level, finally, one tries to understand differences and similarities between the ways in which individuals face reality and lead their lives, how they develop and express their personality and identity, their relations toward other individuals, etc. At this level we speak of Lifestyles. Lifestyles are thus expressions of individuals' ambitions to create their own specific personal, cultural and social identities within the historically determined structural and positional framework of their society. Thus, the term lifestyle is here defined as a structurally, posititionally and individually determined phenomenon.

The reason for making the above distinction is that the application of the concept of lifestyle has changed in accordance with societal and cultural change. In classical sociology, the concept was mainly used to distinguish between basically social classes or status groups on the basis of their cultural characteristics (see Weber 1922/1968; Simmel 1904/1971; Veblen 1899/1979). In contemporary society, on the other hand, lifestyle has become less tied to the social position of the individual; instead, individually determined conditions have become increasingly important for researchers within the area (see Toffler 1970; Zablocki and Kanter 1976; Schudson 1986; Turner 1988).

IDENTITY

We deal with the concept of identity by distinguishing three components inherent in the identity of an individual: personal, social and cultural identity (Johansson and Miegel 1992). These three components of identity are to be considered as aspects of one and the same phenomenon, namely, the total identity of the individual. The three aspects, then, are not to be mistaken for distinct types or categories of identity.

In brief one can explicate the differences between these aspects of identity in the following way. Through the personal identity, the individual develops the capacity to live and think in isolation from others as an autonomous being. This aspect of identity is formed and developed through the process of individuation which results in the personality of the individual (Blos 1962,1967, 1979; Mahler 1963; Mahler et al. 1975). The personal identity consists of experiences, thoughts, dreams, desires as interpreted and comprehended by the individual in relation to other experiences and thoughts. Personal identity thus relates to the individual. It may be described as a unique system of relations between experiences, thoughts, dreams, hopes and desires.

Through his or her social identity the individual becomes a member of different groups, learning the roles he or she is expected to play. This aspect of identity serves the function of integrating the individual in different social contexts. Social identity is formed and developed through the process of socialization and is manifested in the processes of role-enactment, role distance and role-transition (Mead 1934/1962; Goffman 1969, 1982; Turner1968, 1990; Burke and Franzoi 1988). It serves the function of making the individual capable of playing certain roles in social life. In a sense, social identity is non-individual. Its function is to define the individual's position within the society, relations toward other individuals sharing the same position, and the relations towards individuals holding other social positions.

Through the cultural identity the individual becomes able not only to express his or her unique characteristics within the group to which he or she belongs, but also to express towards other groups his or her own group membership or belongingness. The cultural identity is formed and developed through the process of lifestyle development (Johansson and Miegel 1992). The cultural identity can be said to have a double, or integrating, function. On the one hand, it is related to the personal identity, and on the other, to social identity. The individual uses his or her values, attitudes and actions to maintain and develop the personal identity, but also to distinguish him— or herself or relate to other individuals. Thus, one and the same value, attitude or action may on one hand serve the purpose of strengthening the self, and on the other function as a means of expressing a sense of belonging to, or holding distance toward, other individuals.

VALUE

Culture consists of the values the members of a given group hold, the norms they follow, and the material goods they create. Values are abstract ideals, while norms are definite principles or rules which people are expected to observe. (Giddens 1989/1991: 31). The rather broad definition of the concept of value proposed by Giddens in the above quotation points to the theoretical as well as empirical difficulties inherent in the concept, one central characteristic being its abstract nature. However, in the same quotation Giddens also marks the importance of the concept within the social sciences by making it the most fundamental component of culture. Obviously, the lifestyles developed in a society constitute one aspect of that society's culture. Hence, the most important concept in relation to identity and lifestyle is value. Actually, value is the most fundamental component of lifestyle, and one can say that the lifestyle of an individual is an expression of his or her values, the norms related to these values, etc. But value is, indeed, a complicated concept to deal with, and in order to make it suitable for lifestyle analysis, I have to make a number of conceptual distinctions. On the one hand I distinguish between three conceptual levels on which lifestyle can be studied from a values perspective, and on the other, I distinguish between at least four different types of value (Miegel 1990; Johansson and Miegel 1992).

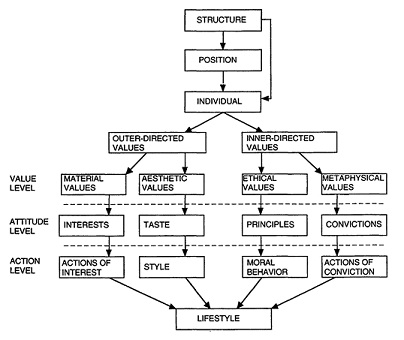

In brief, the lifestyle phenomenon can be studied on three conceptually different levels: a value level, an attitude level, and an action level. The value level consists of the individual's general and abstract ideas about material, aesthetic, ethical and metaphysical conditions and qualities. These rather abstract ideas are made concrete by the individual on the attitude level. The attitudes of an individual involves his or her outlook on specific objects, phenomena and conditions of reality. On the action level, finally, the individual manifests his or her attitudes in the form of different actions. The values and attitudes of the individual become visible and observable when they manifest themselves in action. To summarize: the individual embraces a number of values which he or she makes concrete in the form of attitudes. Such attitudes are expressed in the form of certain actions and behaviours.

As indicated above, I distinguish between four different types of value, namely, material, aesthetic, ethical, and metaphysical values. Each of these types of value corresponds to a type of attitude and a type of action (Figure 10.1).

Most empirical and a good deal of the theoretical lifestyle studies hitherto conducted are concerned basically with the left-hand side of the figure, that is, with material and aesthetic values, attitudes and actions. The most important reason for this is probably that material and aesthetic expressions of value are rather easy to make empirically accessible, since to a considerable extent they have to do with consumption. I will argue here that the right-hand side of the figure — that is, the ethical and metaphysical values —represents an important component of the lifestyle of an individual.

VALUES AND IDENTITY

To understand the relation between identity and value, we turn to the widely influential work of Milton Rokeach. According to Rokeach, a value is an enduring belief, either prescriptive or condemning, about a preferable or desirable mode of conduct or an end-state of existence. These values are organized into value systems along a continuum of relative importance (Rokeach 1973). Rokeach believes that values are taught to human beings, and once taught they are integrated into an organized value system in which each value is arranged in relation to other values. The values serve different functions for the individual. They constitute standards guiding our behaviour, helping us to make decisions, for example in our presentation of ourselves to others, in our comparisons of different actions or objects, in our attempts to influence others, in our formulations of our attitudes, in our evaluations and our condemning of others, and so forth.

Figure 10.1 Values, attitudes and actions

Rokeach's theory of value is accompanied by a number of assumptions about human nature. He maintains that there is a group of conceptions more central to an individual than are his or her values. These are the conceptions individuals have about themselves. Rokeach argues that the total belief system of an individual is functionally and hierarchially structured, so that if some part of the system is changed, other parts of it will be affected, too, and consequently their corresponding behaviour as well. The more central the changing part of the belief system is, the more extensive the effects will be.

A change in the conception of one's self would thus affect and lead to changes also in the values. Rokeach's main thesis is that:

… the ultimate purpose of one's total belief system, which includes one's values, is to maintain and enhance … the master of all sentiments, the sentiment of self regard. (Rokeach 1973: 216)

Before proceeding, it is useful to place Rokeach in a philosophic value theoretical context, since the assumptions inherent in his work are far from unquestioned.

SOME REMARKS ON VALUE THEORY

In Chapter 12, Thomas Johansson distinguishes between a cognitive and an affective dimension of lifestyle, maintaining that values constitute the former dimension, whereas the latter consists of affects, desires and pleasure. The dimension as such offers no great problem, but locating the values within the cognitive dimension calls for discussion. The reason for his doing this is that most social scientists involved in value studies have had what might be called a cognitivist definition of the value concept — including Rokeach, whose theory Johansson takes as his point of departure. In our joint dissertation, too, we somewhat unreflectedly applied a rather cognitivist value definition (Johansson and Miegel 1992: 62). Against this background it is hardly surprising that Johansson defines value in a cognitivist fashion and regards values as belonging to a cognitive dimension of lifestyle. The question, however, is whether values are to be defined in this way. It has long been disputed within the philosophy of value (cf. Bergstrdm 1990; Frankena 1963/ 1973; Hare 1981; Moritz 1973).

In brief, one can identify two basic lines of argument in this debate, one represented by so called cognitivist theories of value, and the other by so called non-cognitivist theories.1 In contrast to the cognitivist theories, the non-cognitivist theories state that value statements are not judgements, but expressions of emotions, or preferences, or imperatives, and thus neither true nor false.

Against this brief value theoretical background, it is clear that the theory suggested by Rokeach, and applied by us in our study, is not self-evident, but in fact rather questionable from a value theoretical point of view, especially since the non-cognitivist theories have been dominant in the post-war twentieth century philosophy of value. Aware of this theoretical limitation or naivety, we have, nevertheless, judged Rokeach's approach as the most suitable among the available social scientific empirical value studies.

VALUES, IDENTITY AND THE CONSTRUCTION OF LIFESTYLES

Lifestyles are routinised practices, the routines incorporated into habits of dress, eating, modes of acting and favoured milieux for encountering others; but the routines followed are reflexively open to change in the light of the mobile nature of self-identity. Each of the the small decisions a person makes every day — what to wear, what to eat, how to conduct himself at work, whom to meet with later in the evening — contributes to such routines. All social choices (as well as larger and more consequential ones) are decisions not only about how to act but how to be. (Giddens 1991: 81)

In studying the relation between values, identity and lifestyle, it is necessary always to keep in mind that the identity is a complex system of relations consisting of a multitude of conceptions about who one is, and how one is related to other individuals and to one's society and culture. Put in other words, identity has a number of different psychological functions for the individual.

First, it has the function of cultivating the personal self, that is, the qualities and characteristics we believe are tied to our own unique person. In this sense, identity functions as a means to help us to maintain and enhance the conceptions we have about ourselves, to identify ourselves, define ourselves for ourselves, to speak, as well as to express this unique self to others, to show others who we are.

Secondly, identity has a number of social functions for the individual. Apart from the desire to have a unique personal identity, people have a desire to be part of their society or culture, and of a variety of different groups existing within it. People often define themselves in relation to groups to which they feel they belong. People play different social roles. Consequently, they sometimes need to subordinate their personal identity in favour of various role expectations.

Thirdly, identity serves the function of integrating and making compatible with one another the desire to be unique with the desire to belong (Johansson and Miegel 1992; Ewen 1988).

The integration of these two desires is not always unproblematical. We are constantly occupied with the struggle to integrate these two poles of identity, and we do not always succeed; conflicts often occur (see Turner 1978).

First, the different expectations related to the roles one plays are not always entirely compatible with one's desire to develop and express one's personality. Thus, the expectations directed towards a certain role may be experienced as obstructing one's potential to achieve one's desire to maintain and develop the qualities and characteristics inherent in what one sees as one's own unique personality.

Secondly, the qualities and characteristics identified as one's own unique personality may lead to difficulties in adopting a certain role. Thus, although one would like to play a particular role, or to occupy a certain position in society, one is prevented from doing so by, say, low self-esteem, or political opinion, for example.

Thirdly, one's social identity consists of multiple roles, and it may be difficult to combine these different roles into a coherent picture of one's social self. One must constantly balance between these different roles, and at the same time take into consideration all the different role expectations. To find a satisfying balance between the different roles one has to play and these roles and one's own personal strivings and aspirations, is something which is difficult but which individuals must endeavour to achieve throughout their whole life.

The different psychological functions of the identity discussed above obviously correspond with different functions of values and lifestyles also. An important distinction is therefore that between security and developmental values (Johansson and Miegel 1992). This distinction resembles Rokeach's distinction between the ego-defensive function of values and the knowledge or self-actualization function of values (Rokeach 1973: 15). The security values (cf. ego-defensive values) serve the function of helping oneself to fit in and adapt in an unproblematic way to society, avoiding conflicts and ensuring that one's actions and attitudes are justified. In Rokeach's terms, such values represent ‘ready made concepts provided by our culture that such justifications can proceed smoothly’ (Rokeach 1973: 15f). The developmental values (cf. knowledge or self-actualization) serve the function of fulfilling the individual's needs and desires to search for meaning, understanding, knowledge and self-realization.

For some individuals, security is the most important function of values, and vice versa. Obviously, which function an individual emphasizes most has a considerable impact on the way his or her lifestyle is constructed (see Zablocki and Kanter 1976; Mitchell 1983).

In order to understand how individuals construct their identity, it is important to comprehend how they reason and act in order to solve the never-ending conflicts between their different roles; and between their roles and their self-images. Society's culture provides a large number of images and ideals for the ways in which particular roles may be successfully acted out, and an equally great number of ideals and images concerning individuality and personal identity. Finally, culture offers a number of ideals and images concerning solutions to the problem of bringing the two poles of identity together.

In the development of the lifestyle of an individual all the components of identity distinguished here are at work. Lifestyle consists of actions and attitudes based not only on material and aesthetic values, but also on metaphysical and ethical values, attitudes and actions. I have argued that any lifestyle involves a meaningful pattern of relations between values, attitudes and actions of all possible kinds. It is thus impossible to keep the different types of value apart in discussing identity and lifestyle. The same is true for the relation between the individual and society. In contemporary Western society the different types of value — material, aesthetic, ethical, and metaphysical — are mingled together in consumer goods and the mass media. As Stuart Ewen puts it:

… in the perpetual play of images that shaped the mass-produced suburbs, and in the ever-changing styles that kept the market in consumer goods moving, ‘material values’ and values of ‘mind and spirit’ were becoming increasingly interchangeable and confused. (Ewen 1988: 232)

Trust

So far I have argued that the values embraced by an individual are the most fundamental components of his or her identity and lifestyle. In order to function in society, a human being must share with his fellow human beings a set of commonly held values, norms, conceptions, etc. The individual must, therefore, internalize these values, norms and conceptions in order to become integrated in society. The process through which this internalization takes place is socialization. As a matter of fact, the most important function of socialization is to integrate the individual into society.

As modernization gradually made society increasingly complex, socialization became a complicated process indeed. While in pre-modern times socialization prepared the individual to function together with a relatively limited number of persons, socialization in late modern society must prepare the individual to function within highly complex systems and structures.

Against this background Niklas Luhmann and others have pointed to the importance of the concept of trust in socialization theory (Luhmann 1973/ 1979; cf. Giddens 1991). According to both Luhmann and Giddens, trust is necessary if the individual is ever to develop and to function in society. Without trust, everything in society will be experienced as threatening and uncontrollable, and the individual will experience a kind of isolation in reality, which may lead to existential anguish. Giddens and Luhmann believe that this important ability to experience trust is established during childhood in relation to the nearest environment, that is, parents, siblings, peers, etc. To establish this trust in the individual is thus a basic function in socialization.

Luhmann maintains that trust is a mechanism which helps the individual to deal with the complexity characterizing modern society. A complex society demands that an individual's trust be based on the insight that he or she is indeed dependent on a very complex system. According to Luhmann, individuals and social systems alike strive to create a kind of predictability in reality — that is, to establish reasonable expectations about how individuals and social systems work.

The establishment of trust during childhood and adolescence provides the individual with a sense of security. We learn what is expected of us, and what we can expect from others in different contexts. The establishment of trust, therefore, to a considerable extent is based on the learning of norms and rules of different kinds, the ‘do's and don'ts’ of social life. Once internalized, these norms and rules function as a kind of guarantee for individuals that they can expect some reasonable continuity and stability in the ways people act and react in different situations. In this sense, trust is related to that aspect of identity which I call social identity. Giddens (1991) uses the term ontological trust to describe the individual's need for a predictable environment over which he or she has at least some control, in order to be able to trust the existence of some continuity and stability in the numerous relations on different levels which constitute the individual's social network.

Thus, the ability to trust is an essential prerequisite for the individual to develop a stable identity and a socially acceptable lifestyle. The process through which the individual internalizes the necessary values, norms and conceptions is, therefore, one of the most important factors in the development of the individual's identity and lifestyle. A good deal of this process takes place during childhood and adolescence in relation to family experiences (cf. Chapter 1).

However, apart from learning social rules and norms, the individual is, of course, also developing his or her personal identity during childhood and adolescence. Here, too, the individual's family is of utmost importance in controlling the individual's degree of freedom, and in encouraging the development of his or her individual needs, desires, experiences, attitudes, etc. In short, on the one hand, the individual must learn a number of norms and rules in order to adopt and fit into a variety of social contexts, and, on the other, must develop an autonomous individual personality. The communication climate of the family in which the individual is brought up, therefore, sets the necessary conditions for the individual's identity and lifestyle development in adult life, one of the most important aspects of family related socialization being the relative importance assigned to social and personal identity development, respectively.

So far I have discussed theoretically the relation between the values embraced by the individual and the lifestyles the individual develops. I have furthermore discussed the fundamental role of the early socialization and the establishing of trust in the individual's value, identity, and lifestyle development. I have argued that a fundamental role in this process is played by the family in which the individual is brought up, and, thus, that the communication ideology within the family may have at least some impact on which values and lifestyles the individual will develop.

In the rest of this chapter I shall present some empirical findings in support of the previous arguments concerning the relation between values and lifestyle, and between socialization and the learning of values.

AN EMPIRICAL INTRODUCTION

In this section I will briefly report on the instruments used to measure values, lifestyle and family communication. Within the Media Panel Program a considerable amount of theoretical and empirical work has been conducted on these subjects. Family communication has been studied by Hedinsson (1981) and Jarlbro (1986, 1988). The relation between value and lifestyle has been analysed mainly by Lööv and Miegel (1989, 1991), Johansson and Miegel (1992), Miegel (1990) and Miegel and Dalquist (1991).

We have used three different sets of questions for studying the values of our respondents. Two are well-known empirical instruments developed by Ronald Inglehart (1977) and Milton Rokeach (1973), and one of them we have developed ourselves.

In brief, Rokeach identified eighteen values which he took to cover the entire and universal value sphere. His technique is usually termed List of Values (LOV). It may be used in at least two different ways. Rokeach himself used the ranking technique, which means that the respondents must arrange the eighteen values in order of preference. In our study, however, we have used a rating technique. We have also added six values to Rokeach's eighteen values. I cannot account for the theoretical and methodological reasons behind this choice of approach here, however. (For a thorough discussion of these matters, see Johansson and Miegel (1992). For a discussion of ranking vs. rating techniques, see, for instance, Munson (1984), Alwin and Krosnick (1985), De Casper and Tittle (1988).)

Contrary to Rokeach, Inglehart does not identify particular values. Instead, he uses what might be described as an indirect method of identifying the value orientations of the respondents: he measures the respondents' attitudes towards twelve concrete societal goals for the future. Like Rokeach he uses a ranking technique, whereas in our study we have employed a rating technique. In brief, Inglehart's method aims at identifying two different value orientations: a material one and a postmaterial one. Inglehart states that in contemporary society individuals have not only become more able to influence their own lives, but have also come to put higher value on self-development, personal growth, life satisfaction and the like. No longer having to put as much effort into the mere satisfaction of fundamental biological and material needs, the contemporary Western person has become increasingly preoccupied with self-development. Inglehart thus indicates that in Western societies a gradual shift in value orientation is taking place. The earlier emphasis on material welfare and physical security has decreased, greater attention being paid to such phenomena as self-fulfilment, self-realization and personal growth. This is the process he calls a shift from a material to a postmaterial value orientation in contemporary society (Inglehart 1977, 1990).

Part of our own constructed value measurements resembles Inglehart's, but we had our respondents rate their attitudes towards fourteen different goals for their own future, instead of using Inglehart's societal goals. Using this method we can identify four types of personal value orientation: individual security, individual development, social security and social development. In short, the value orientation of individual security encompasses such future goals as having a stable relationship and children; individual development goals such as travelling a lot, living abroad and having an exciting job. Social security stresses such personal goals for the future as earning money, having a safe job, a car of one's own, working full-time, and looking young. Social development, finally, includes goals such as investing in education and making a career.

Two types of lifestyle indicator were used in the study. We measured the individuals' attitudes towards music and film, and also the relative frequency with which they pursue different leisure time activities. We asked our respondents about their attitudes towards 53 different music genres, and 37 different film genres. To make the material more manageable we employed factor analysis to arrive at a number of taste patterns, as we like to call them. These taste patterns may be interpreted as a number of quite general patterns of taste in music and film, towards which the respondents relate in differing ways depending on their class, gender and education, and also depending on which values they hold. From these factors we created twelve additive indices of music taste and nine indices of film taste, each of which can be used in further statistical analysis (Johansson and Miegel 1992). The same procedure was used for the measurement of leisure time activities. From a list of 56 different activities we created eleven additive indices, or activity patterns.

In order to measure family communication we have applied two versions of Chaffee's measurement method (Chaffee et al. 1973; cf. Ritchie 1991). Chaffee distinguishes between socio-oriented family communication and concept-oriented communication patterns. Socio-oriented family communication tends to stress the importance of smooth social relations with other people, while the concept-oriented family emphasizes the importance of ideas and concepts (Chaffee et al. 1973; Jarlbro 1986; Rosengren and Windahl et al. 1989). In this study we use two different sets of questions to identify these dimensions. We applied the original set of questions when the respondents were 15 years old. At this time the respondents' parents reported on how the communication within the family took place. We used a revised version when the respondents were 21 years old. At this time they responded themselves on how they thought family communication ought to be.

There are, however, several difficulties involved in measuring family communication, some of which I will briefly mention here. One obvious problem is that we have measured one particular family member's (in most cases the mother's) perception of norms, rules and ideals governing family communication (Ritchie 1991). Different family members may have different views on these matters; daughters may be raised differently than sons; father and mother may have different attitudes concerning children's upbringing, and so on. Furthermore, the measurement does not account for gender or age related positions and distributions of power within the family. Nor does it account for the existence of different types and sizes of family. Communication within a family consisting of only a single parent and one child is probably radically different from that in a family with two parents and several children. There are also children with two families, two ‘fathers’, two ‘mothers’ and two sets of siblings, and communication in these families respectively may, indeed, vary.

Apart from the problems related to the family, there are also problems associated with the fact that from a rather early age, just like children in many other countries, most Swedish children spend a great deal of time in social institutions (first in child care centres, then at school). A considerable part of the early socialization, therefore, takes place outside the family, and in relation to adults and peers other than parents and siblings. The relative impact of the family and these institutions respectively on which values, norms and ideals the individual internalizes, are, therefore, of utmost importance when discussing how family communication may influence individually developed values.

The list of problems related to the measurement of family communication and its influence on the individual may be further extended (for instance, by the role of the mass media in the process of socialization), but I stop here by establishing the fact that the measurement of family communication and its impact on the individual entails several difficulties which I cannot solve here. I can only point them out and keep them in mind when interpreting the statistical analyses presented later in this chapter (cf. also Chapter 8).

ADAPTION AND PROGRESSION

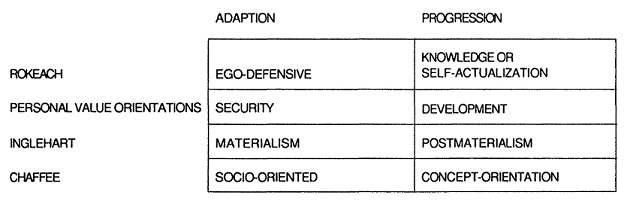

Taking a close look at the different measurement scales used when measuring values, value orientation and family communication, we find that the dimensions supposedly tapped by these scales show interesting similarities. It may even be possible to locate them within two separate categories which we may call Adaption and Progression (Figure 10.2). The former category emphasizes the importance of fitting in and adapting in an unproblematic way to the environment, the avoidance of conflicts, smooth relations with other people, and the securing of social and material relations, whereas the latter stresses such aspects as personal growth, self-development, personal independence, self-actualization, supportiveness and open communication.

In the category of adaption we may place Rokeach's ego-defensive values, which serve the function of helping one to fit in and adapt in an unproblematic way to society. Inglehart's material value orientation can also be assigned to this category, emphasizing material needs, stable social relations, and societal order. Likewise, the personal value orientations of individual and social security belong to this category, since they stress stable social, material and economic relationships. Finally the socio-oriented family communication pattern, stressing the importance of smooth social relations with other people, the avoiding of conflict, and clear-cut power positions, also belongs to the category of adaption.

Figure 10.2 The categories of adaption and progression

The category of progression includes Rokeach's knowledge or self-actualization values, serving the function of fulfilling the individual's needs and desires to search for meaning, understanding, knowledge, and self-realization. Also Inglehart's postmaterial value orientation, stressing self-development, personal growth, life satisfaction, etc., belongs to this category, as do the personal value orientations of social and individual development with their emphasis on social, material and personal development and growth. Finally, also, Chaffee's concept-oriented family communication pattern can be assigned to the category of progression, due to its emphasis on the importance of ideas, concept, personal independence, open communication, and the like.

From this we may argue that the four different measurement scales in different ways aim at capturing different aspects of one and the same phenomenon in modern society, namely, the process of individualization, which will be discussed in more detail in the concluding part of this chapter. This means that we should expect statistical correlations between the four adaption dimensions, and between the four progression dimensions. And, as a matter of fact, there are such correlations.

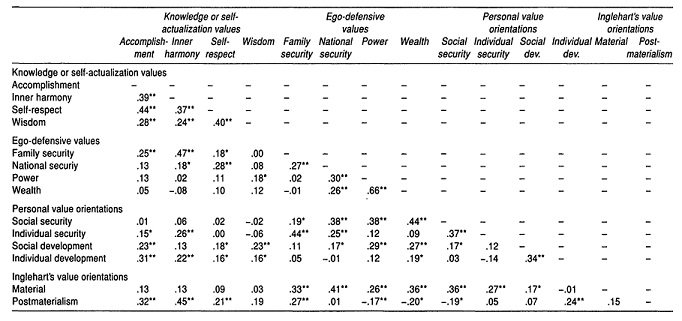

Table 10.1 presents the correlations between the four Rokeachean values most representative of his knowledge and self-actualization dimension (self-realization, inner harmony, self-esteem, wisdom), and the four values best describing his ego-defensive dimension (family security, national security, power, wealth); it also includes Inglehart's materialism and postmaterialism dimensions, and the four personal value orientations. The table speaks for itself. The variables belonging to the adaption category tend to correlate with each other, as do the variables belonging to the progression category. However, there are few correlations between the progression variables and the adaption variables.

These results further support the assumption that the different methods of measuring value may capture different aspects of one and the same phenomenon. As will be shown later in this chapter, the same seems to hold true for the relation between the values/value orientation and the socio-oriented family communication pattern. Furthermore, the statistical variation within the variables are generally considerably greater in the variables I have assigned to the adaption category. Whereas most people in our sample seem to agree more or less upon the statements used when measuring progression, they show generally much more variation in their attitudes toward the statements used to capture the dimensions included in the adaption category.

One may thus pose the question what kind of information we gain from the analysis of the relation between values and family communication. If the different scales measure basically the same phenomenon, albeit at different conceptual levels, the results obtained should be expected. And this is actually what I argued earlier in this chapter. According to the discussion, the value structure of a society has an impact on which values the individuals of that society internalize, which in turn influences their attitudes towards, in this case, how family communication ought to take place. Put in another way, if the value structure of a society (Inglehart) has impact on which values the individuals within this structure embrace (Rokeach), and if the values the individual embraces constitute the basis for that individual's attitudes in various areas (Chaffee), we should expect correlations between the variables used to measure each of these levels. That is precisely the results obtained. I will return to a discussion of these matters later in the chapter.

Table 10.1 Knowledge or self-actualizing values, ego-defensive values, personal value orientations and Inglehart's value orientations (Pearson's correlations)

YOUTH CULTURE AND LIFESTYLE: THE IMPORTANCE OF VALUES

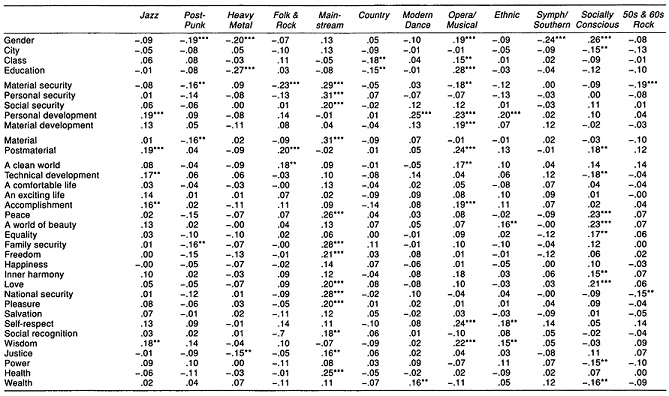

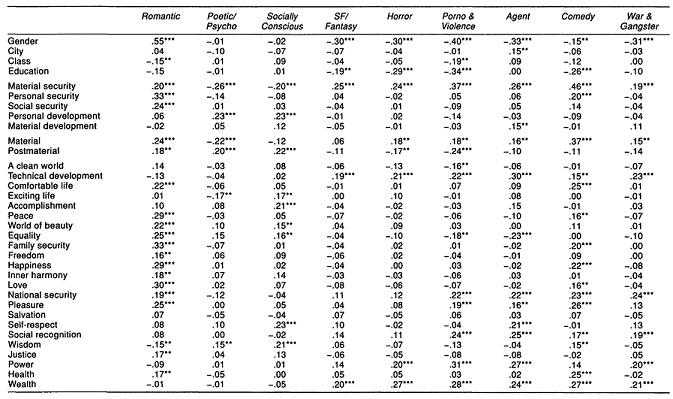

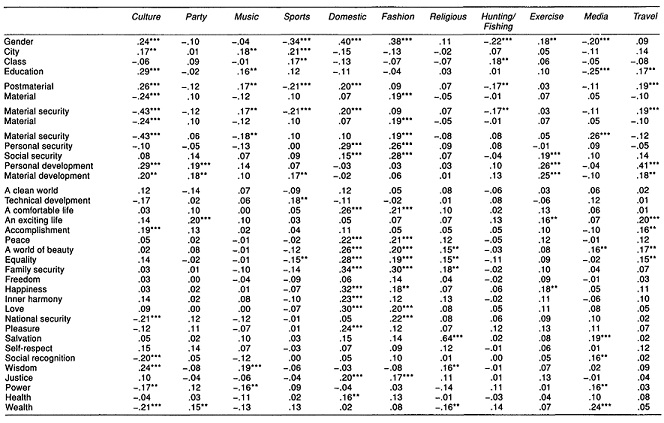

The empirical results presented in Tables 10.2,10.3 and 10.4 may be regarded as providing a rough and preliminary indication of how young people's lifestyles are structured.

There are a large number of different relations present in the tables, and these can be interpreted on the basis of several different theoretical perspectives. I shall briefly discuss three such theoretical perspectives: a class-and status-oriented perspective, a gender perspective and a human values perspective.

The class and status perspective may be regarded as the dominant perspective within the sociological literature on popular culture and lifestyles (see Weber 1922/1968; Gans 1974; Bourdieu 1984). According to this perspective, the most important structural principle here is the distribution of wealth and status in society. The most thoroughgoing theoretical and empirical work within this tradition is probably Bourdieu's Distinction. Our empirical results give some support to the assumption that class and education are important factors in the development and maintenance of lifestyles.

We note that several taste and activity patterns correlate with either class or education or both. Thus, the levels of education and class background seem to be related to the development of certain tastes and leisure time interests. Even though class and education constitute important and necessary explanations of the way young people develop particular lifestyles, these variables do not suffice for providing an adequate explanation. Also age, which, however, is kept constant in the analyses, and gender are important factors to consider.

On the basis of our empirical data we conclude that differences between men and women in their tastes and leisure time activities, and in their lifestyles, are considerable. These differences are, of course, related to gender roles. On a more general level it is also possible to discuss these differences in terms of two differing cultural spheres, namely, a male and a female sphere. However, just as with class and education, gender is a necessary but not sufficient explanation of the differentiation of lifestyles within a society.

Apart from gender, class and education, there are also other structurally,

Table10.2 Musical taste related to positional variables, values and value orientations (Pearson's correlations)

Table 10.3 Film taste related to positional variables, values and value orientations (Pearson's correlations)

Table 10.4 Leisure time activities related to positional variables, values and value orientations (Pearson's correlations)

positionally or individually determined phenomena which influence an individual's lifestyle. Among these are identity and the values embraced by the individual him-–or herself.

In one way or another, all the different taste and activity patterns distinguished in this study are related to at least some values and/or value orientations. The relations between values and value orientations on the one hand, and taste and activity patterns on the other, are rather complex. These relations are partly explained by the ways in which values among youth in Western society are structured along the gender, class and status dimensions. From the simple correlation matrices presented in Tables 10.2, 10.3 and 10.4 we cannot gain insight into the complex relations between values, societal position, and tastes or activities. Thus we have conducted a number of combined Anova-MCA analyses in order to arrive at a more thorough knowledge of the empirical relations between these different variables.

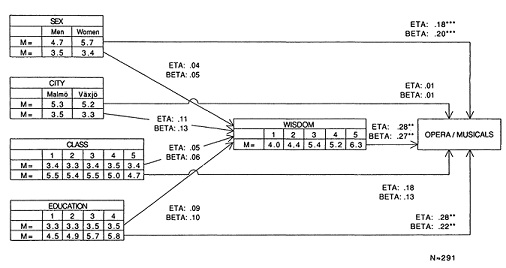

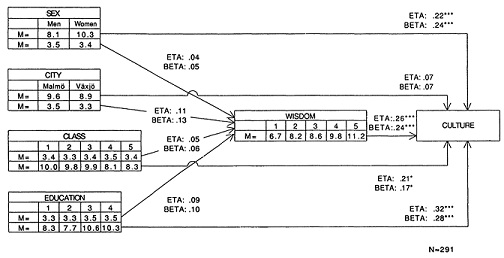

In order to carry out a complete analysis of the relations between these variables, we would have to conduct an Anova-MCA analysis for all the thirty values and value orientations concerning their relation to each of the twelve musical taste patterns, the nine film patterns and the eleven activity patterns, making for a total of 30x32=960 Anova-MCA analyses. I cannot, of course, present such a number of analyses here. Instead I have chosen three such analyses to exemplify the complex relations to be found between structure, position, values and lifestyle which I have discussed in the theoretical part of this chapter (see Figures 10.3, 10.4 and 10.5).

It should be noted that the Anova-MCA analyses presented here are chosen among the fifteen showing the strongest correlation between a value and a taste or activity pattern.

Obviously, not every Rokeachean value is correlated with every taste or activity pattern. I could, therefore, just as well have presented a handful of examples of Anova-MCA analyses showing no correlation between a particular value and a taste or activity pattern. By presenting the Anova-MCA analyses in Figures 10.3, 10.4and 10.5,1 am thus not aiming at proving that each given taste or activity pattern is determined by a particular value. All I want to do is to show that at least some taste and activity patterns are clearly correlated with a value, and that some of the variation within a given such pattern seems to be explained by the degree to which that value is held. That is, the very existence of such correlations is what is interesting in this context; not the particular correlation. Put differently, the existence of correlations between some values and some taste and activity patterns, even when controlling for other variables, can be taken as an indication that the values which an individual embraces constitute one explanation, among others, for that individual's tastes in music and film, and her leisure time pursuits.

I am, of course, aware that in order to let the unique influence from each particular value on each particular taste or activity pattern stand out, we should have to keep not only gender, education, city and socio-economic

Figure 10.3 Anova-MCA analysis of the relations between structural and positional variables, the value of wisdom and the musical taste pattern of opera musicals

Figure 10.4 Anova—MCA analysis of the relations between structural and positional variables, the value of family security and the romantic film taste pattern

Figure 10.5 Anova-MCA analysis of the relations between structural and positional variables, the value of wisdom and the culturally oriented activity pattern

status constant, but also all the other values and probably some other variables. Given the capacity of the Anova-MCA, where only five variables can be kept constant during an analysis, this is, unfortunately, impossible to accomplish.

In the figures we account for each positional variable's unique influence on a value, and on a taste or activity pattern. In the same figure we account for the unique influence of a specific value on a specific taste or activity pattern. Each figure is based on nine single analyses in which the relation between two variables was investigated while the influence of other relevant variables was kept constant.

The figures show that even when positional variables are held constant the relations between values and taste or activity patterns are strong. Thus, the values and value orientations of the individual tell a great deal about the way the individual's own personal lifestyle develops within the structurally and positionally determined framework characterizing the person's society and culture.

The values embraced by the individual are inculcated into him or her by parents and peers at school or at work, as well as through other societal institutions, during the processes of individuation and socialization. Eventually all persons learn to function as individuals who incorporate the general material, aesthetical, ethical and metaphysical codes of society and culture, as well as those of the particular groups and social networks in which they become involved during their lifetime. This adjustment to more or less commonly held values, norms, mores, etc. is necessary in order to function as a social being. However, there are considerable variations, both between different groups in society and between different individuals, with respect to the relative importance put on these values, norms, mores, and the like.

One might say that although most individuals share a common set of values, norms and mores with their fellow people, they nevertheless deviate from one another in their unique ways of relating to these values, mores and norms. Thus, the values and value orientations distinguished by Rokeach and Inglehart are all embraced more or less by all individuals, but the relative importance ascribed to each single value varies from person to person. These variations are important; obviously, they exert a strong influence on the more specific attitudes and actions of the individual. These individual variations, in their turn, are translated into the many highly differentiated lifestyles found in society.

The social and cultural structure of modern Swedish society is characterized by rather small variations in values between different classes and status groups among youth, but by rather strong variations between young men and women (see Table 10.5). It should be noted in this context that this state of affairs concerns young people in Sweden. The results may look different for other age-groups or for the Swedish population as a whole.

In our sample it is thus difficult to distinguish between the values and value

Table 10.5 Values and value orientations related to gender, class and education (Pearson's correlation)

| Gender | Class | City | Education | |

| Material security | -.14 | -.07 | -.03 | -.14 |

| Personal security | .15** | -.07 | .04 | -.10 |

| Social security | .19*** | .04 | .03 | .02 |

| Personal development | .11 | .15** | -.04 | .08 |

| Material development | -.08 | .20*** | .06 | .20*** |

| Material | .02 | .04 | -.01 | -.08 |

| Postmaterial | .35*** | -.04 | -.12 | -.02 |

| A clean world | .18** | -.05 | .00 | -.07 |

| Technological development | -.39*** | .15 | .04 | .08 |

| A comfortable life | .11 | .04 | -.09 | -.15 |

| An exciting life | .05 | -.04 | -.04 | -.11 |

| Sense of accomplishment | .14 | .03 | .06 | .00 |

| Peace | .30*** | -.07 | -.11 | -.14 |

| A world of beauty | .22*** | -.08 | -.10 | -.23*** |

| Equality | .39*** | -.14 | -.17** | .11 |

| Family security | .30*** | -.07 | -.10 | -.08 |

| Freedom | .16** | .06 | -.03 | -.07 |

| Happiness | .30*** | -.02 | -.16** | -.10 |

| Inner harmony | .24*** | .06 | -.08 | -.01 |

| Love | .27*** | .00 | -.10 | -.12 |

| National security | .02 | .00 | .10 | -.03 |

| Pleasure | .09 | -.09 | -.09 | -.16 |

| Salvation | -.02 | -.03 | -.08 | .00 |

| Self-respect | .09 | .15 | -.02 | .18** |

| Social recognition | -.08 | -.04 | .03 | -.10 |

| Wisdom | -.04 | -.01 | -.12 | .07 |

| Justice | .26*** | .03 | -.09 | -.06 |

| Power | -.23*** | .03 | .02 | -.07 |

| Health | .10 | .03 | -.07 | -.07 |

| Wealth | rtQ*** | .06 | -.01 | -.08 |

orientations embraced by different classes or status groups. Young people possessing higher education and coming from higher-class backgrounds do tend to emphasize the importance of development as opposed to security more than do individuals of lower education and of lower-class background. But the major differences are to be found along the gender dimension. Actually, we can identify a large number of values and value orientations tied to gender differences.

These gender differences are also expressed in variations in taste and activity patterns. Although there are class-–and status-related taste and activity patterns, there are even greater gender-related patterns. Tables 10.2, 10.3, 10.4 and 10.5 show that there are strong relations between the gender-related values and value orientations, and the gender-related taste and activity patterns. This seems to imply that values and value orientations, as well as taste and activity patterns, are strongly influenced by gender. The interesting fact, though, is that even when gender is kept constant, the often rather strong influence of a particular value or value orientation on a taste or activity pattern remains intact (see Figures 10.3, 10.4 and 10.5). Thus, the tendency to embrace certain values and value orientations and to develop certain taste and activity patterns is closely related to gender. At the same time, irrespective of gender, class and education, individuals embracing particular values are more or less likely to develop certain taste and activity patterns.

FAMILY COMMUNICATION AND THE ESTABLISHMENT OF VALUES AND TRUST

So far I have argued that behind lifestyles in contemporary society lie a number of individually embraced values. At the structural level, these values are part of a long-term cultural heritage. At a positional level they are tied to the various positions which individuals occupy within these structures. At an individual level they are part of the individual's own identity. I have furthermore presented support for these assumptions in some empirical findings regarding the relations between positional variables, lifestyle variables and value variables. Investigating how these values are transmitted to the individual from various agents of socialization (be it parents, siblings, peers, the mass media, church, school or any other societal institution), I now turn to the notion of socialization.

As individuals, we must all be able to trust our environment to a certain degree, in order to adopt the basic values and become able to act upon them and thus to function socially and to establish a lifestyle and identity of our own. The basic aspect of this necessary trust is founded during childhood and early adolescence in relation to one's family. Therefore, the family is an agent of socialization of extreme importance. The communication pattern of a family may be regarded as one plausible indicator of how socialization is taking place within a family.

In this section I will supply some empirical findings with a bearing on the relation between the family communication pattern and the values developed by individual family members. Taking as our point of departure Chaffee's socio-oriented dimension of family communication (see above), I shall investigate differences in values between the individuals in our sample. (I will not use his concept-oriented dimension since the variables used to measure this dimension show only little variation in our sample. That is, most respondents seem to agree upon the desirability of a concept-oriented family communication.)

Socio-oriented communication may be described as rather authoritarian, involving clear power relations between the family members (i.e., parents and children), stressing such factors as avoiding conflict, obeying, not getting angry, not arguing, showing respect for the elderly, etc.

We can first establish that there is a certain degree of stability between how the respondents' parents scored on the socio-oriented communication dimension when the respondents were 15 years old, and how they themselves scored at the age of 21 (Pearson's correlation 24***). The really important question, however, is whether the degree of socio-oriented communication pattern in the family has any impact on how the respondents score on the value variables.

I divided the population into three groups. One-third scored low on the socio-oriented dimension, one-third scored medium, and the remaining third scored high. When comparing the low-scoring third with the high-scoring third, I found some interesting differences in the scores also on the value and value orientation variables (Tables 10.6 and 10.7). In the tables the fifteen Rokeachean values which show the largest variations between the groups are included, together with the four personal value orientations, and Inglehart's postmaterial and material value dimensions. The values not included in the table show only small or no variation between the groups.

Turning first to Table 10.6, which includes the parental reports on the family communication when the individuals were 15 years old, and the values they held at the age of 21, we find that the individuals whose parents scored high on the socio-oriented dimension, tend to score higher on values and

Table 10.6 Scores on value and value orientation variables at age 21, for low, medium, or high scores on the socio-oriented dimension of family communication at age 15 (parental reports; means)

| Value | Low | Medium | High |

| Power | 0. 75 | 0.49 | 1.24 |

| Pleasure | 2.78 | 2.86 | 3.22 |

| Social recognition | 1.61 | 1.43 | 1.98 |

| Exciting life | 2.46 | 2.62 | 2.76 |

| A beautiful world | 2.82 | 3.22 | 3.12 |

| National security | 2.79 | 2.70 | 3.08 |

| Salvation | 0.24 | 0.47 | 0.51 |

| A comfortable life | 3.17 | 3.27 | 3.43 |

| Wealth | 1.41 | 1.08 | 1.66 |

| Happiness | 3.38 | 3.41 | 3.60 |

| Family security | 3.18 | 3.41 | 3.39 |

| Love | 3.58 | 3.59 | 3.74 |

| Health | 3.58 | 3.78 | 3.73 |

| Equality | 3.01 | 2.89 | 2.93 |

| Social security | 13.16 | 12.95 | 14.36 |

| Individual security | 5.71 | 5.84 | 6.15 |

| Social development | 5.55 | 4.86 | 5.38 |

| Individual development | 7.86 | 2.30 | 7.35 |

| Material | 16.53 | 16.64 | 17.09 |

| Postmaterial | 20.14 | 19.16 | 19.51 |

Table 10.7 Scores on value and value orientation variables at age 21, for self-reported low, medium, or high scores on the socio-oriented dimension of family communication at age 21 (means)

| Value | Low | Medium | High |

| National security | 2.79 | 2.80 | 2.13 |

| Technological development | 2.19 | 2.02 | 2.50 |

| Wealth | 1.44 | 1.27 | 1.74 |

| Salvation | 0.35 | 0.45 | 0.64 |

| Pleasure | 2.95 | 2.93 | 3.20 |

| Self-respect | 2.91 | 2.72 | 2.66 |

| Power | 0.92 | 0.76 | 1.17 |

| Social recognition | 1.68 | 1.71 | 1.92 |

| A beautiful world | 2.95 | 3.11 | 3.19 |

| A comfortable life | 3.23 | 3.38 | 3.43 |

| Equality | 3.07 | 2.95 | 2.89 |

| Family security | 3.31 | 3.38 | 3.47 |

| Wisdom | 2.55 | 2.30 | 2.39 |

| Freedom | 3.76 | 3.75 | 3.61 |

| Happiness | 3.47 | 3.51 | 3.60 |

| Social security | 12.61 | 13.69 | 14.81 |

| Individual security | 5.55 | 5.89 | 6.41 |

| Social development | 5.57 | 5.28 | 5.31 |

| Individual development | 7.77 | 7.50 | 7.23 |

value orientation which have to do with security, materialism and status. As to the Rokeachean values, we find that those individuals whose parents scored high on the socio-oriented dimension tend to score higher also on the kind of values which Rokeach interprets as ego-defensive, and values which emphasize security, that is, values such as social recognition, family security, salvation, wealth, a comfortable life, national security, happiness, love and health. We also note that they tend to score higher on values stressing power and status, for instance, power, social recognition, and wealth. This indicates that individuals raised in families oriented towards socio-oriented communication — stressing the importance of avoiding conflict, fitting in unprob-lematically with society, enjoying security, appreciating a fixed and rather authoritarian distribution of power between the family members — themselves tend to adopt values expressing such features. This tendency gains further support from the fact that these individuals also tend to score higher on the personal value orientations which emphasize the security dimension, i.e. social security and individual security, but lower on the development dimensions, i.e. social development and individual development. They also tend to score higher on Inglehart's dimension of material value orientation, and lower on his postmaterial value dimension.

We may thus conclude from these results that the scores on those values and value orientations which I assigned to the category of adaption tend to be higher if the score is high also on the socio-oriented family communication pattern.

The results presented in Table 10.7 show basically the same pattern. On the one hand, individuals scoring high on the socio-oriented communication pattern tend to score higher also on the values and value orientations belonging to the adaption category, and lower on these belonging to the progression category. On the other hand, the individuals scoring low on the socio-oriented communication pattern tend to score higher on the values and value orientations belonging to the progression category and lower on these belonging to the adaption category.

It is indeed tempting to take these results as supporting our assumption that there is a relation between the family communication and the values internalized by the individual, and to some extent that is so. The relations accounted for in Table 10.6 describe the relations between the scores of the respondent's parents on the socio-oriented communication pattern when the individuals were 15 years old, and the respondents' own reports on the values and value orientations at the age of 21. These results thus indicate that the family communication pattern during upbringing influences the strength with which the individual embraces certain values at adult age. Although the patterns found in Tables 10.6 and 10.7 are clear enough, the tendencies are rather weak and statistically not significant. This has probably several explanations. In the first place, the variations within each of the variables used are rather small, and so is the sample analysed. Another explanation may be that the measurement scales used are not sufficient to capture successfully the variations in the phenomena they are supposed to measure. Yet another, perhaps more plausible and definitely more tempting and interesting explanation is that the absence of statistically significant correlations reflects a gradual long-term change of the overall societal structure. It is to this explanation I shall now direct my attention.

CONCLUSIONS

In this chapter I have argued that the values embraced by an individual constitute a fundamental part of that individual's identity and lifestyle, and that these values are internalized by the individual through the process of socialization. Assuming that an important part of the socialization takes place within the family, I hypothesized that the communication climate in the family is related to the values internalized by the individual. These assumptions are not very controversial— as a matter of fact they are rather commonly held among those involved in socialization theory. Empirically to study and measure values, family communication and the process of socialization is, however, difficult. Hence the statistical analyses which I have presented as supporting our assumptions must be interpreted with some caution. The first question to consider is whether the different instruments used when measuring values, value orientations and family communication basically aim at capturing one and the same phenomenon. During the last few decades there has been a discussion within sociology and social psychology regarding the development of a new personality type during the twentieth century. In brief, this discussion emphasizes the view that during the last century or so, most people in Western societies have experienced a rise in the satisfaction of material needs. They do not have to put as much effort into satisfying these basic needs; consequently they have become more concerned with phenomena such as life-satisfaction, self-expression, personal growth and fulfilment, etc. This is the process Inglehart (1977) tries to capture in his The Silent Revolution. Although Inglehart does not use the term personality type himself, we can, nevertheless, use his terminology and describe the new personality type as post-materialistic. Inglehart is far from alone in having noticed this process, however. It has been studied and analysed by several social scientists during the latest fifty years or so.

A number of commentators have suggested that a new personality type has emerged in the course of the twentieth century. David Riesman (1950), for example, refers to the replacement of the ‘inner-directed’ by the other-directed type and Daniel Bell (1976) mentions the eclipse of the puritan by a more hedonistic type. Interest in this new personality type has been sharpened recently by discussions of narcissism. (Featherstone 1991: 187)

Also Rokeach's discussion of the ‘master of all sentiments, the sentiment of self regard’ (1973: 216) follows this line of argument. Featherstone (1991) speaks about the new personality type in terms of a ‘performing self, and Goffman has noted the increasing importance of the ‘presentation of self in everyday life’ (Goffman 1982).

Following these theoreticians there is no doubt that the twentieth century has witnessed an increased interest in identity, lifestyle and personality. It is this process which Inglehart and Rokeach study, and it may be argued that Chaffee's studies of family communication basically concern the same process, the concept-oriented individual representing the new personality type. Given this state of affairs, we may interpret our empirical findings about the relations between family communication and values as providing further support for the hypothesis about the increasing importance of the individual's personality development. This is reflected, for example, in the fact that all our respondents scored high on the concept-oriented communication dimension.

It is indeed probable that there exists a relation between family communication and the individual's values. All the same, the results presented in this chapter are best interpreted as suggesting a long-term process taking place in modern Western societies, a gradual change of the societal structure affecting also the positional and individual levels of society and culture.

It is mandatory, then, that media and communication research concerned with youth and youth culture look closer at how this process is also reflected in the mass media. There is no doubt that popular culture and the mass media constitute leading sources from which young people receive the images and ideas they use in their identity and lifestyle work. The mass media, therefore, have an important role as agents of socialization and as transmitters of values, norms and attitudes, something which obviously has considerable impact on the importance of the role of the family in the process of socialization. The relation between the two agents of socialization, the family and the mass media, therefore remains an important issue to study if we are ever fully to understand the role of family communication in the shaping of young people's lifestyles and identities.

NOTE

1. Although it is impossible to account for the entire scope of this extensive philosophical debate here, it is nevertheless important to pay at least some attention to it. The notion of value has been, and is, an extremely ambiguous and ever-disputed concept within philosophy. Thus the location of value within a cognitive dimension of lifestyle is not at all self-evident, but, as we shall see, actually a rather questionable standpoint.

To begin with the cognitivist theories, we can identify at least two leading types of theory, namely, naturalistic and objectivistic value theories. The former seem to be the most common ones within the social sciences. Mitchell's (1983) and Inglehart's (1977; 1990) theories both rest on naturalistic assumptions about the nature of values. Also Rokeach's (1973) theory is founded on a special branch of value naturalism, namely, subjectivism (see Johansson and Miegel 1992). In brief, naturalist theories of value state that norms and valuations are natural, scientific or empirical statements. That is, an ethical or aesthetic term can be defined in terms of non-ethical or non-aesthetic terms. Such theories have been subject to severe and devastating criticism within the philosophy of value, and within modern philosophy they are almost totally abandoned. The best-known argument held against naturalistic theories is different formulations of Hume's Law, stating in its most commonly known form that it is impossible to derive ‘ought’ from ‘is’ (Hume 1740/1982; Mackie 1980; Hare 1981).

The other basic form of value cognitivism is the so-called objectivistic value theories. These theories are also called non-naturalist theories; they deny that value statements express empirical value judgements, but agree that value judgements can be objectively true or false. This is the kind of theory held by, for instance, Plato, Kant, Sidgwick, and Moore (Bergström 1990; Frankena 1963/ 1973). Although objectivistic theories of value have not been totally abandoned, they have nevertheless been somewhat out of fashion in the twentieth-century value philosophy.

During the twentieth century different forms of non-cognitivist theories of value have emerged and become dominant. Several different forms of such theories have developed throughout the century, the best-known being the so-called emotivism —which according to Bergstrom (1990) gained almost total acceptance in Sweden — and later also the so-called prescriptivism (Bergström 1990; Mackie 1980) and universal prescriptivism (Hare 1981). Mackie (1980) describes the differences between the theories as follows:

Emotivism: a moral statement expresses, rather than reports, a sentiment which the speaker purports to have, and, by expressing it, tends to communicate it to a suitable hearer…

Prescriptivism: in judging morally about a proposed action, a speaker is commanding or forbidding it. This is developed into Universal Prescriptivism: a moral statement endorses a universalizable prescription which the speaker is implicitly applying, or is prepared to apply, to all relevantly similar actions, irrespective of their relation to himself. (Mackie 1980:73)

REFERENCES

Alwin, D.F. and Krosnick, J.A. (1985) ‘The measurement of values in surveys: A comparison of ratings and rankings’, Public Opinion Quarterly,49: 535–552.

Bell, D. (1976) The Cultural Contradictions of Capitalism, London: Heinemann.

Bergstrom, L. (1990) Grundbok i värdeteori, Stockholm: Bokförlaget Thales.

Blos, P. (1962) On Adolescence, New York: The Free Press.

— (1967) ‘The second individuation process of adolescence’, The Psychoanalytic Study of the Child,22: 162–186.

— (1979) The Adolescent Passage: Developmental Issues, International Universities Press.

Bourdieu, P. (1984) Distinction. A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste,Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

Burke, P.J. and Franzoi, S.L. (1988) ‘Studying situations and identities using the experiental sampling method’, American Sociological Review,4: 559–568.

Chaffee, S.H., McLeod, J.M. and Wackman, D.B. (1973) ‘Family communication patterns and adolescent political participation’, in I.J.Dennis (ed.)Socialization to Politics, New York: Wiley.

Dalqvist, U. (1991) Insamlingsrapport 1988 och 1990, Lund: Sociologiska Insti-tutionen.

De Casper, H.S. and Tittle, C.K. (1988) ‘Rankings and ratings of values: counseling uses suggested by factoring two types of scales for female and male eleventh grade students’, Educational and Psychological Measurement,48: 375–384.

Ewen, S. (1988) All Consuming Images. The Politics of Style in Contemporary Culture, New York: Basic Books.

Featherstone, M. (1991) ‘The body in consumer culture’, in M.Featherstone, M.Hepworth and B.S.Turner (eds)(1991) The Body. Social Process and Cultural Theory, London: Sage.

Frankena, W.K. (1963/1973) Ethics, London: Prentice Hall Inc.

Gans, H.J. (1974) Popular Culture and High Culture. An Analysis and Evaluation of Taste, New York: Basic Books.

Giddens, A. (1989/1991) Sociology, Cambridge: Polity Press.

— (1991) Modernity and Self-identity. Self and Society in a Late Modern Age,Oxford: Polity Press.

Goffman, E. (1969) Where the Action Is: Three Essays, London: Penguin Books.

— (1982) The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life, Harmondsworth: Penguin Books.

Habermas, J. (1987) The Theory of Communicative Action. Volume 2. Lifeworld and System: A Critique of Functionalist Reason, Boston, Mass.: Beacon Press.

Hare, R.M. (1981) Moral Thinking. Its Levels, Method and Point, Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Hedinsson, E. (1981) TV, Family and Society: The Social Origins and Effects of adolescents' TV Use, Stockholm: Almqvist & Wiksell International.

Heller, A. (1970/1984) Everyday Life, London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Hume, D. (1740/1982) A Treatise of Human Nature. Books Two and Three, London:Fontana/Collins.

Inglehart, R. (1977) The Silent Revolution: Changing Values and Political Styles Among Western Publics, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

— (1990) Culture Shift in Advanced Industrial Society, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Jarlbro, G. (1986) ‘Family communication patterns revisited: reliability and validity’,Lund Research Papers in the Sociology of Communication 4, Lund: Department of Sociology, University of Lund.

Jarlbro, G. (1988) Familj, Massmedier och Politik, Stockholm: Almquist & Wiksell International.

Jarlbro, G., Lööv, T. and Miegel, F. (1989) ‘Livsstilar och massmedieanvändning. En deskriptiv rapport’, Lund Research Papers in the Sociology of Communication 14,Lund: Department of Sociology, University of Lund.

Johansson, T. and Miegel, F. (1992) Do The Right Thing. Lifestyle and Identity in Contemporary Youth Culture, Stockholm: Almqvist & Wiksell International.

Kamler, H. (1984) ‘Life Philosophy and Lifestyle’, Social Indicators Research, 14(1): 69–81.

Lööv, T. and Miegel, F. (1989) ‘The Notion of Lifestyle: Some Theoretical Contributions’, The Nordicom Review,1: 21–31.

Lööv, T. and Miegel, F. (1991) ‘Sju livsstilar. Om några malmöungdomars drömmaroch längtan’, Lund Research Papers in the Sociology of Communication,29, Lund:Department of Sociology, University of Lund.

Luhmann, N. (1973/1979) Trust and Power, Chichester: John Wiley & Sons.

Mackie, J.L. (1980) Hume's Moral Theory, London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Mahler, M.S. (1963) ‘Thoughts about development and individuation’. The Psychoanalytic Study of the Child 18: 307–324.

Mahler, M.S., Pine, F. and Bergman, A. (1975) The Psychological Birth of the Human Infant, New York: Basic Books.

Mead, G.H. (1934/1962) Mind, Self and Society: From the Standpoint of a Social Behaviorist, Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Miegel, F. (1990) ‘Om värden och livsstilar. En teoretisk, metodologisk och empirisk oversikt’, Lund Research Papers in the Sociology of Communication,25, Lund:Department of Sociology, University of Lund.

Miegel, F. and Dalquist, U. (1991) ‘Värden, livsstilar och massmedier. En analytisk deskription’, Lund Research Papers in the Sociology of Communication,31, Lund: Department of Sociology, University of Lund.

Mitchell, A. (1983) The Nine American Lifestyles. Who We Are and Where We Are Going, New York: Warner Books.

Moritz, M. (1973) Inledning i värdeteori, Lund: Studentlitteratur.

Munson, M. (1984) ‘Personal values: considerations on their measurement andapplication to five areas of research inquiry’, in R.E.Pitts and A.G.Woodside (eds)Personal Values and Consumer Psychology, Toronto: Lexington Books.

Riesman, D., Glaser, N. and Denny, R. (1950) The Lonely Crowd, New Haven, Conn.:Yale University Press.

Ritchie, L.D. (1991) ‘Family communication patterns. An epistemic analysis and conceptual reinterpretation’, Communication Research,18 (4): 548–565.

Rokeach, M. (1973) The Nature of Human Values, New York: The Free Press.

Rosengren, K.E. (1991) ‘Media use in childhood and adolescence: invariant change?Some results from a Swedish research program’, in J.A.Anderson (ed.)Communication Yearbook,14: 48–90, Newbury Park, Calif.: Sage.

Rosengren, K.E. and Windahl, S. (1989) Media Matter. TV Use in Childhood and Adolescence, Norwood, NJ: Ablex Publishing Corporation.

Schudson, M. (1986) Advertising, the Uneasy Persuasion: Its Dubious Impact on American Society, New York: Basic Books.

Simmel, G. (1904/1971) ‘Fashion’, in D.N.Levine (ed.) On Individuality and Social Forms, Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Thunberg, A.M., Nowak, K., Rosengren, K.E. and Sigurd, B. (1981) Communication and Equality. A Swedish Perspective, Stockholm: Almqvist & Wiksell.

Toffler, A. (1970) The Future Shock, New York: Random House.

Turner, B.S. (1988) Status, Milton Keynes: Open University Press.

Turner, R.H. (1968) ‘Role’, in D.L.Sills (ed.)International Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences, New York: Macmillan and the Free Press.

Turner, R.H. (1978) ‘The role and the person’, American Journal of Sociology, 1:1–23.

Turner, R.H. (1990) ‘Role Change’, Annual Review of Sociology,16: 87–110.

Veblen, T. (1899/1979) The Theory of the Leisure Class. An Economic Study of Institutions, Harmondsworth: Penguin Books.

Weber, M. (1922/1968) ‘Class, status, party’, in H.H.Gerth and C.W.Mills (eds)From Max Weber.Essays in Sociology, London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Zablocki, B.D. and Kanter, R. (1976) ‘The differentiation of life-styles’, Annual Review of Sociology,2: 269–298.