CHAPTER

Three

The Hero’s Journey and the Structure of Game Stories

If you ask a dozen writers what the hardest part of writing a story is, you’ll probably get a dozen different answers. The character development, the ending, the discipline to simply sit down and write: it varies from person to person. But every writer, regardless of style and preferences, has to start in the same place. Before you can write a story, you need an idea.

For many writers, coming up with ideas is easy. In fact, at times the greatest challenge can be deciding which idea to focus on. When working on games, you may not even have to worry about the initial idea. Depending on your position and the team structure, you may have a basic idea or even a full outline given to you by the creative director or lead designer and be tasked with expanding it into a full-fledged story.

“I Think I’m Gonna Write the Great American Game Story”

Since the advent of 3D engines, what most often happens when you talk about story development in games is that either an idea for a certain type of gameplay springs into being and a story is concocted to support that gameplay idea, or marketing wants a game in a certain type of genre, so the team begins to search for a story idea to fit the genre. Those kinds of situations are the most common when the story idea comes along early in the game development process. But if an idea for an original great story

pops into someone’s head, outside the world of games, I’m not sure the initial way to express that story would be, “I’ll tell that story as a game.” More likely, the creator of that idea would start to write a novel, a screenplay, a live play, or maybe a pilot for a television series. This distinction is one of the difficulties in the actual development of original game stories. Often the best story ideas take some other form first because games are not known primarily for their story, but rather their gameplay. And that makes existing story adaptation into a game (if it ever reaches that point) even more difficult.

—Chris

Either way, taking that basic idea and expanding into a full-length tale that’s suitable for games is a very important task and one that, if done incorrectly, can easily turn even the best ideas into dull, uninteresting stories. To help you prepare for this process, we’ll start out by examining which types of stories are best suited for games and why, then move on to study a classic story structure that is used as the basis for a wide variety of stories, especially in the game industry. We’ll also take a look at some of the common themes and clichés present in game stories and discuss when they should and shouldn’t be used.

If you’re just starting out as a writer, these guidelines will give you a solid foundation on which to begin your writing. If you’re already experienced with creating story ideas and structures, consider this a review and look at the case studies to see how those elements are used in video games.

Types of Stories Best Suited for Games

As a storytelling medium, video games offer many advantages over print and film. Like TV shows and movies, video games provide a full audiovisual experience complete with “sets” (levels), “actors” (digital characters), voices (spoken lines delivered by real-life actors), music, and sound effects. However, unlike film, video games are not limited to short stories or “story chunks” that can be told in thirty minutes or two hours. Depending on the type of game and the resources of the team creating it, a game can span anywhere from several to over one hundred hours. Typical games, however, tend to last between ten and twenty hours for action, adventure, and FPS titles and between forty and sixty hours for RPGs. Of course, only a portion of that time is occupied by the story; the rest is filled with exploration, fighting, puzzle solving, and the like. But their length gives games far more time to set up complex plots and develop characters than the average movie or TV show. In this way, games are similar to books.

Let’s spend a little time expounding on the nature of dramatic stories and how they operate differently in the mind of the player/audience.

Difference #1

Novels/fiction take place in the mind of the reader, and the reader generates all the images for the story (setting, characters, props). All drama has, on the other hand, already generated the “look” of the piece for the audience. The audience sees the locales, the actors/characters, the costumes, and so on, all looking the way the creators want them to. This can be a good thing or a bad thing from the audience perspective, but regardless, it places the brain of the viewer in a different place than a novel does.

Difference #2

Novels can be read over time; in fact, the reader controls the pace at which the story is consumed. The reader may stop, skip ahead, reread, skip to the end and then go back, and so on. The reader is totally in charge of the way the way the story is consumed. In drama, stories happen much more quickly, and always at the pace of the creators. There is no going back to recheck facts, reexamine clues in a murder mystery, or anything like that. The story unfolds in front of the audience, and the audience has to keep up. They must pay attention to get all the information they need. In fact, the authors use tricks to get something to “land” with the audience (meaning that it is understood and remembered), and any information that is crucial must often be told and retold and reiterated many times and in different ways to an audience so that it will stand out in their minds by the time the climax arrives. This balance, between staying one step ahead of the audience so they don’t figure out the story too quickly and giving the audience enough reminders of crucial info so they don’t forget, is one chief challenge and difference of dramatic writing compared to narrative fiction. This is why structure (defined as the sequence of events) is so important in drama – much more so than in fiction. The time-bound nature of drama makes it a very different way of thinking about the writing. It is less about language and more about the way the story unfolds.

Difference #3

The audience is usually aware in narrative fiction of what characters are thinking and feeling. In fact, getting inside a character’s head is one of the joys of reading fiction. In drama, the audience can never know what a character is thinking. All they know is what the character does. Feelings and thoughts are often implied. So characters’ emotional states in fiction can be told through their thoughts, but we know characters’ emotions in drama only by what they do. Even what they say may be suspect, as the best kind of dialog in drama always layers in subtext, where the intention and meaning may differ from the surface words. This interplay is why actors’ performance is so crucial in drama.

This dichotomy leads to many delicious moments in drama, as characters reveal their motivations that they have hidden from us through their actions (think about Toy Story III when Lotso the bear revealed that he hadn’t “joined up” with Woody and the gang only when he refused to help them escape from the furnace). Hidden knowledge is used quite differently in narrative fiction than in drama. So, in order to use this technique, stories must be structured differently, and characters must behave differently. Thus, the techniques of seeing the visuals, controlling the pace of the story, and showing characters by what they do combine in a way that makes dramatic stories very different for the audience as well as the writer.

—Chris

Games also have other advantages that are uniquely theirs, all of which tie into their interactive nature. As previously mentioned, games create a framework that can be used to let players make important decisions and change the progression and outcome of the story. And even if the main story itself remains unchangeable, interaction has other advantages. The addition of optional side-quests, for example, gives the player the chance to pursue other tasks and quests that although not vital to the main plot can be used to provide additional details and expand on the world and story. In-game books, journals, and the like can serve a similar purpose, allowing players to delve deeply into the details and backstory or simply ignore them and focus on the main plot.

“Dear Diary, Today I Leveled Up”

The tools mentioned so far augment the “show, don’t tell” nature of drama and must be used carefully as they affect the pace at which the story is consumed. Too often they can be used as a crutch, as story elements that rightly ought to sit on the screen as player activities or NPC interactions become journal entries instead, owing to time or budgetary constraints. On the positive side, using this technique can pull into the game some of the more enjoyable elements of the narrative style, where we can enjoy what a character we may never have met was or is thinking.

—Chris

For many players, the interactivity also helps them form a close bond with the characters much more easily than in print and film. Regardless of how much control the player has over the story, during the game he or she does, to a certain extent, become the main character, sharing the hero’s triumphs and failures. With the player taking an active role in the process, the thrill of defeating a powerful foe or the agony of a being unable to save a dear friend becomes all the more real. We’ll be talking more about the unique emotional experiences that can be created in games throughout the rest of this book, especially in Chapter 5.

Despite these advantages, telling stories in games has its drawbacks as well. For example, depending on the type of game and the storytelling method used, game stories can require considerably more time and effort to create than a typical book or movie script. Keeping a strong pace and maintaining player interest can be difficult over the course of a long game (which is discussed in Chapter 4) and interactivity itself provides a host of new and difficult challenges, which is an issue we’ll be dealing with throughout this entire book. And, aside from all that, there’s the simple and undeniable fact that some types of stories just don’t work well in games – at least not without a lot of extra planning and effort.

A Writer’s Challenge

Perhaps the biggest difficulty in creating compelling game stories is that the story is really out of the writer’s control. What I mean is this: in a film, once the script is greenlit, 99 percent of the time they shoot pretty much what’s on the page (lines may change, but whole scenes rarely get altered in a big way). There are exceptions, but not all that much. Now, in the final edit things may indeed change, but I’m saying that for the most part, they shoot what’s been written. So if the writer’s structure doesn’t work, it’s pretty much his or her own fault. In games, they almost never build the whole story as written; whole levels (which are about the same as an “act” in traditional written media) can be (and are often) cut, mostly at the last minute, after other levels (acts) that occur later in the story have already been built, so you can’t go back and fix the issue or smooth it over, and the writer is seldom consulted when these events occur. These cuts occur for mostly good and proper reasons, mind you, but this is not the ideal process for the writer. Thus, even the most artfully crafted story structure can come undone at the last minute as the writer is left to patch together sequences that may not make as much sense as they once did.

—Chris

Although stories in modern games cover a very wide range of genres and styles, if you look closely, you’ll see that some story types that are extremely popular in books or on TV are poorly represented or even entirely nonexistent when it comes to games. For example, games have action and adventure stories written in a multitude of styles and set in nearly every conceivable time and place, but where are the game equivalents of romance novels, sitcoms, and real-world coming-of-age stories? Some say that it’s a matter of demographics and that your average gamer simply isn’t interested in those types of stories, but the true problem can be found by looking at the basic principle of video games themselves.

When you break video games down to their very essence, you’ll see that above all else, they’re games. I know: not exactly a shocking revelation. But think about it. What’s the one thing every single game from Monopoly to World of Warcraft has to have, regardless of its style, genre, or platform? The answer, of course, is gameplay. Whether it’s practicing cut-throat business techniques or exploring a monster-infested wilderness, a game needs to provide the player with something entertaining to do besides merely watching the story unfold. As a result, video games tend to focus on fighting and strategy, exploration, puzzle solving, or some combination of the three. These types of external conflicts are far easier to portray in a game-like fashion than the more internal emotional conflicts that are often the focus of things like romance novels and sitcoms. Therefore, a “proper” game story needs to support a large amount of external conflict.

It also makes it a lot simpler both for designers and players if the story focuses on only a single character or group of characters. Jumping back and forth between a lot of different people not only requires more design work, but also makes it difficult for the player to get used to playing as any one specific character. This issue can be fixed easily if all the characters play exactly the same, but that tends to annoy players who rightly believe that a teenage girl shouldn’t move and fight in the same way as a hardened war veteran. Stories with a lot of character swapping can be done well in games, but it takes a lot more thought and balance on the design side to keep the gameplay smooth.

Who Are You?

The nature of the interactive world is that one player identifies with one character on the screen. Most great designs clearly define who you are in the game. Perhaps that is an overlord controlling a population or a solitary soldier with an automatic weapon. Regardless, the one-to-one correspondence is clearly laid out.

When you allow a player to control multiple identities, the player mentally shifts into a state where he or she starts to feel like a god and actually like none of the characters on the screen.

—Chris

When you look at things from this perspective, the lack of certain story types makes quite a lot of sense. It’s only natural for stories about soldiers, mercenaries, and alien invaders to include a lot of battles while stories about detectives and treasure hunters provide many opportunities for exploration and puzzle solving. With stories like those, you don’t need to try and force the gameplay to fit with the story or vice versa – they work together easily. From a basic story perspective, a space marine fighting aliens makes perfect sense. Trying to find a good reason for a sitcom dad to be fighting hordes of enemies or making a series of death-defying leaps, however, is much more difficult.

Just because some types of stories aren’t easy to use in video games doesn’t mean that they can’t be done – you just need to work a bit harder to create the necessary synthesis of story and gameplay. The passion-filled storytelling style of romance novels, for example, is skillfully re-created in Japanese dating sim (“simulation”) games. In dating sims such as Konami’s popular Love Plus, the player takes the role of a boy or girl (depending on the game) and is tasked with getting through daily life while befriending and carefully building and maintaining a relationship with one or more characters. The gameplay is often dialog-heavy and tends to focus on time management (hanging out with friends, going on dates, studying, working, and so on) and figuring out the right things to do and say to win the heart of your chosen girl or guy. Though dating sims are very popular in Japan, they’re rarely, if ever, released overseas.

Though few pure dating sims are currently being released in English, if you’re curious about the genre and can’t read Japanese, a few Japanese RPGs featuring a large number of dating sim elements, including some titles in the Sakura Wars series and the PlayStation cult classic Thousand Arms, have been released in the United States. You can also get English releases of some rather heavily adult-oriented dating sims from Jbox (http://www.jbox.com).

For another example of how to turn a nonideal story into an excellent game, just look at Flower. In Flower, several potted flowers sit on a windowsill in a dark and dreary city, dreaming of sunny days and grassy fields. As a story, the idea sounds much better suited for something like an experimental film than a video game. Yet Flower’s zen-like gameplay, which has the player guiding a cluster of flower petals blowing in the wind in order to bloom more flowers and open up new paths, and simple yet well-done story won over gamers, making it one of the top-selling downloadable games on the PlayStation 3.

These are only two examples; there are many more out there. What games like Love Plus and Flower prove is that just about any type of story can be made into a good video game. Using nonideal story types is difficult and requires a lot of creativity and careful planning in order to ensure that the story and gameplay make sense and work well together, but it can be done.

Now that you understand a little bit about the nature of game stories, it’s time to talk about their structure. The structure can best be thought of as the basic progression or outline of your story. For example, in a romantic comedy the structure usually looks something like Figure 3.1.

FIGURE 3.1

A typical romantic comedy story structure.

Though overly generic, the example in the figure makes for a solid structure around which the majority of romantic comedy stories are based – all you need to do is tweak the details a bit to personalize it and make it stick out. But chances are good that you won’t be using the romantic comedy structure very often in video games, so let’s take a look at a more useful one.

The hero’s journey is not just a story structure, it’s the story structure, at least when it comes to certain types of stories, such as those about heroic quests, epic adventures, and journeys of enlightenment. The hero’s journey is the story structure on which ancient myths and legends from around the world are based. Many early civilizations’ greatest stories such as Gilgamesh, Beowulf, and the Iliad and the Odyssey make use of the hero’s journey, as do a large number of modern stories, especially when it comes to things like fantasy novels and video games. The hero’s journey is such a logical structure and so prevalent in literature that even writers with no formal knowledge of it often unknowingly use it in their stories.

The Writer’s Journey

The gentleman who “uncovered” the Hero’s Journey, Joseph Campbell, has often commented that the journey itself is a kind of proto-story, turning up as much as it does in the mythologies of the world in part because it links us to our essential selves. In other words, it tells the story of what it means to be human. In that manner, he has described the story structure as being embedded in our DNA. I believe that it is, because the journey’s structure is found in many stories written by authors who may not be aware of the structure’s formal definition. Also, because the structure is commonly found in fairy tales and because most Western authors heard those stories when they were being put to bed as children, the structure is unconsciously echoed time and time again. That is partly why it resonates for us so intently.

—Chris

Be sure to keep in mind, however, that the hero’s journey isn’t a story in and of itself – it’s just a basic framework around which to build a story of your own. If you’re having trouble mapping out the progression of your story, the hero’s journey can prove to be an invaluable resource, giving you an idea of what events should take place and what elements your story may be missing. It can also give you ideas for characters, pacing, and other vital elements. With enough creativity and imagination, the hero’s journey can create an endless array of unique and diverse stories. J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter series and George Lucas’s Star Wars, for example, may seem to have little in common, but they both make use of the hero’s journey. Lucas has even publicly acknowledged the influence that Campbell and the hero’s journey had on Star Wars.

Structure of the Hero’s Journey

The hero’s journey can be roughly broken down into three general acts: the departure, the initiation, and the return. Those acts can be further broken down into more specific stages. Depending on exactly how you break things down, you can end up with anywhere from ten to seventeen stages. However, it’s important to note that many of these stages are optional and therefore don’t always appear in stories that use the hero’s journey. The following is my own breakdown of the stages, based on a combination of the seventeen-stage version from Joseph Campell’s The Hero with a Thousand Faces, the twelve-stage version from Christopher Vogler’s The Writer’s Journey, and my own experience with the structure.

It is crucial to understanding the structure that you think of these stages as emotional signposts rather than actual events in your story. That is, you are looking to evoke the feeling of a departure or the feeling of a death in the belly of a whale rather than having a character actually die in the belly of a whale. It is the emotion of the moment that the audience responds to, not the outer wrapper. This is often where young writers become lost as they use the journey’s structure.

—Chris

Stage 1: The Ordinary World

The so-called ordinary world is where we’re first introduced to the hero, who is living out his or her normal everyday life. Of course, depending on the setting and the hero him- or herself, this “ordinary world” could actually be quite extraordinary. For example, life in a magic academy or space marine outpost is anything but ordinary to us, but if you grew up in that type of environment, there really wouldn’t be anything special about it at all.

This time in the ordinary world is a chance to introduce the hero and explain a little bit about who he or she is before the start of the adventure proper. In Harry Potter, Harry’s ordinary world is life with his unpleasant aunt and uncle; for Luke, it’s his uncle’s farm on Tatooine. You want to use this stage to show a bit about the hero’s background and his or her normal life, such as family, friends, and occupation. You shouldn’t give away everything, especially if your hero is really much more than he or she seems, but it’s important to convey a sense of who the hero is and what the hero does or doesn’t stand for.

One important thing to remember is to not let the ordinary world stage run on for too long. Introducing your hero and setting the stage for things to come is all well and good, but if you spend too much time focusing on the hero’s boring everyday activities, players will start to lose interest. Learning that the hero is a farmer in a small town is all well and good, but describing his or her activities on the farm every day for an entire week is probably overkill. Sooner or later, something has to happen!

Stage 2: The Call to Adventure

Naturally, the hero can’t continue going about normal life forever. Sooner or later, something has to break the hero away from the ordinary world and set him or her on the path toward adventure. The call can come in many different forms. At times it’s an actual call, such as Harry’s letter from Hogwarts or Princess Leia’s famous “Help me, Obi-Wan Kenobi” message. At other times, it’s less direct. Hearing rumors of a long-lost treasure, spotting a suspicious figure in the woods, and dreaming of life in another place can all be calls to adventure. The call is anything that starts to take the hero away from normal life and causes him or her to wonder if he or she really belongs in the ordinary world after all.

Depending on your story, the call could be a sudden and immediate event, such as an unexpected enemy attack, or a slow and gradual thing, such as the hero becoming discontented with his or her life. In video games, however, in which you generally want to get the player into the action as quickly as possible, a sudden call is often the best way to go.

It’s also important to think about just what the call is going to be. Usually the call is something related to the main plot like rumors of a treasure or an attack by the main villain, though in some cases the call itself is relatively unimportant, serving only to lure the hero away from the ordinary world and into a position in which later encounters will involve him or her in the main conflict. Sometimes the call is even an attempt to lure the hero into a trap. What the call is and how the hero reacts to it will say quite a lot about the hero’s personality and motivation, so be sure not to gloss over it. A retired space marine may be eager to jump into battle during a surprise alien attack, but a young boy is likely to be scared and more interested in survival than anything else. Keeping your characters consistent and believable is a very important part of good storytelling and one we’ll be covering in depth in Chapters 4 and 5.

Stage 3: Refusing the Call

Stage 3 is an optional stage that reflects significantly upon the hero’s mindset. Although some heroes will accept the call to adventure immediately (removing the need for this stage entirely), others will resist. Maybe they’re scared, maybe they don’t want to leave their ordinary life behind, maybe someone talked them out of it, or maybe they just don’t care. Harry, for example, initially refused to believe that he could possibly be a wizard, as it all just seemed too crazy and impossible; Luke’s uncle urged him to forget about the mysterious message and focus on his normal work. Whatever the reason, if heroes refuse the call, something needs to happen in order to make them change their minds. Quite often, this something is a tragedy or disaster brought about by the hero’s initial refusal to take action, but at times it’s a more benign event, and on rare occasions it even turns out that refusing the initial call was in the hero’s best interests. Either way, by the end of this stage the hero must have answered the call and, willingly or unwillingly, taken his or her first steps toward starting the adventure.

Danger, Will Robinson!

I do not believe this stage is optional at all. It is a crucial point in the story to have either the hero refuse the call (or at least doubt it) or have someone close to the hero tell the hero “Don’t go” or “Aren’t you worried about the danger?” Without this stage, the audience does not appreciate the risk or stakes involved in the journey. The best way to handle this in a game is to have others tell the player how dangerous this path is. The player will never refuse it, of course, but the danger can be made clear.

—Chris

Stage 4: The Mentor

Though some heroes begin their adventure knowing everything they need to know, or at least thinking that they do, others need a bit of information and/or training to help them get started. This is where the mentor comes in. At times the mentor actually provides the call to adventure and/or forces the hero’s hand if the call is refused. At other times, the hero and mentor don’t meet until the adventure is already underway. The cliché mentor is a wise old person – often a wizard or such – who has come to aid the young hero in his or her task. Following the cliché, the mentor’s job is to teach the hero just enough to get by and then die (often in a heroic self-sacrificing way) before having a chance to relay the most important bits of information. Obi-Wan Kenobi is a perfect example of this type of mentor. He teaches Luke the basics of fighting and using the force, but sacrifices himself in the battle against Darth Vader when the adventure has only barely gotten underway.

However, just because it’s a common cliché doesn’t mean that you have to stick to it. Mentors can come in any shape or form, and there’s no law stating that they have to die in the second act. Because the old man mentor is so overused, it often pays to do things a bit differently in order to keep player interest high. In some stories, the mentor is young and only slightly more experienced or knowledgeable than the hero himself like Etna in Disgaea: Afternoon of Darkness. In others, such as Higurashi: When They Cry, the mentor may, either knowingly or unknowingly, end up giving the hero false information, causing more harm than good. At times, the mentor may even betray the hero entirely. And, of course, there are games like FINAL FANTASY VII that don’t have a mentor of any kind. I’ll be discussing all those games in the coming chapters, so keep the hero/mentor relationship in mind when you read their case studies.

Stage 5: The First Threshold

So the hero has answered the call and met the mentor. Now what? To close out the first act, the hero needs to cross the “first threshold” and begin the adventure in earnest. This stage often serves as both the hero’s first big challenge and the point of no return, from which there’s no more avoiding the call or returning to the ordinary life. Battles and long journeys are common types of first thresholds, as are people who are determined, for one reason or another, not to let the hero leave (parents, commanding officers, or similar), but there are many variations.

Luke’s first threshold was escaping from Tatooine on the Millennium Falcon, which involved skill and a certain level of danger; Harry’s occurred when he stepped through the barrier on Platform 9¾ and began his journey to Hogwarts, which required nothing more than an act of willpower on his part. The threshold can also be an event triggered by the hero refusing the call (as previously mentioned). Often the hero will have the mentor to help with this stage of the journey, and it’s also one of the more common times for the mentor to sacrifice him- or herself to save the hero, but at other times the hero will need to take this first step into the great unknown alone and unaided.

This is a time for heroes to strengthen or affirm their resolve and show what they’re really made of. It’s also a good time to give the player the first real challenge in the game itself, perhaps in the form of a tricky puzzle or boss battle. With the first threshold crossed, it’s time to move on to the second act, which constitutes the majority of the story.

Stage 6: The Journey

Despite the fact that there were five stages leading up to this point and five more still to come, this stage actually takes up the vast majority of the story, spanning from immediately after the crossing of the first threshold until the point when the hero has nearly completed his goals. In game speak, that means that this stage goes until the player reaches the final level, dungeon, or quest.

The first thing that should be focused on is showing just how different this new world and life are from the ordinary world where the hero began. In Star Wars, Luke found himself drawn into the battle between the Rebel Alliance and the Empire almost immediately after leaving Tatooine, when his ship was captured by the Death Star. Harry’s train ride to Hogwarts was similarly filled with strange sights and magical happenings, showing him and us that he had truly left the ordinary world behind.

Once the world itself has been established, there’s still plenty of ground to cover. As this stage makes up the bulk of the hero’s journey, it’s full of encounters and adventures. This is when the hero travels about, exploring the world and gaining friends, enemies, and rivals. The hero may fall in love, face loss and betrayal, and be forced to deal with all manner of monsters and obstacles. If the cliché old man mentor is still alive when this stage begins, he’ll be sure to heroically sacrifice himself at some point (occasionally returning later on in a more powerful form). Throughout their travels and trials, the heroes will learn more about the new world and themselves; grow more comfortable, skilled, and confident; and have numerous encounters (some good, some bad) with other people and creatures. They’ll also learn, if they haven’t already, what their eventual goals will be and the things they’ll need to do in order to accomplish them.

Although the Star Wars movies and Harry Potter books can actually be broken down into a series of small hero’s journeys, each occupying a single entry in the series, when we take them as a whole, the journey stage in Star Wars starts when Luke leaves Tatooine and doesn’t end until he and the rebels begin plotting the destruction of the second Death Star in Return of the Jedi (the third movie in the first trilogy). Harry’s journey is long as well, beginning when he boards the train for Hogwarts in the first book and continuing up until the start of the seventh and final book when he begins his search for the horcruxes.

This is your chance to fully take the reins of the story, develop your places and characters, and explore the events that lead up to the final confrontation. Just about anything can happen in this stage, with the only limit being your imagination (and possibly your budget). By the time this stage is complete, the main characters (both heroes and villains) should be known, most mysteries and secrets should have been revealed, and the hero should be almost ready to push forward toward the final battle or challenge and bring the adventure to a close.

Stage 7: The Final Dungeon

My video game–inspired name aside, this stage of the journey doesn’t necessarily have to contain a dungeon or anything of the sort. (However, when you’re writing for video games, there’s a good chance it will.) With the bulk of the quest complete and the goal clearly in sight, this is the stage where the hero makes any final plans and preparations and then goes off to storm the villain’s castle, blow up the alien mother ship, challenge his or her greatest rival to a last duel, prove who the murderer is, or the like.

Luke’s “final dungeon” stage involves the planning for the assault on the second Death Star, the mission to shut down its shield generator, and then the assault itself. Harry’s was his quest to find and destroy the remaining horcruxes in order to strip Voldemort of his near immortality.

The final confrontation itself isn’t part of this stage, but everything leading up to it is. In this stage, you should focus on wrapping up loose plot threads (remaining mysteries, character relationships, and the like) and giving the heroes and the player a chance to show off how much they’ve grown and improved over the course of the adventure. Some of the toughest puzzles, battles, and challenges are usually found in this portion of the story – all leading up to the final confrontation.

That said, it should be noted that you can also create a fake version of this stage at some point during the journey in order to play some mind games and set things up for a big plot twist. In Square Enix’s The World Ends with You, for example, the story centers around a deadly game that lasts for seven days. Against all odds, the heroes, Neku and Shiki, manage to survive until the last day, clear the final challenge, and defeat the ominous figure running the game. But just when it seems that their adventure is at an end, a new villain shows himself and reveals that the game is far from over. These fake or mini final dungeons and challenges, if done correctly, can throw players off balance and/or serve as good transition points between different sections of the story. Just as Luke had a different challenge to deal with at the end of every movie, and Harry a new villain to face and mystery to unravel at the end of every book, game stories can similarly be broken down into volumes or episodes of sorts. In some games, these points merely serve to break up a long story into easily identifiable sections; in others they actually do mark the end of a volume or episode and try to leave the players with a partial sense of closure and a lot of anticipation for the sequel.

Stage 8: The Great Ordeal

This is it: the big moment, the event that the entire journey has been building toward, and the last stage of the second act. At long last, the hero has made it through the final dungeon, and only a single challenge remains. In most video games, and many books and movies for that matter, the great ordeal will take the form of a final boss battle, with the hero facing off against the ultimate enemy. Sometimes it’s a physical battle fought with swords, guns, or magic, like Luke’s battle with the Emperor or Harry’s battle with Voldemort. But in some games, such as Sam & Max: The Devil’s Playhouse, it can take the form of a battle of wits that plays out more like a puzzle than an actual fight. Then there are games such as Braid in which there’s no boss at all and the great ordeal is a final test of the hero and player’s skills.

During the ordeal, the hero often has to face not only the physical villain or challenge but his or her own inner demons as well, and can be victorious only in the physical ordeal by completing the inner ordeal, almost as if the hero is dying and being reborn, a metaphor that in some cases is handled in a very literal fashion. The completion of this ordeal serves as the culmination to much of what the hero has worked for throughout the story and often (though not always) serves as the hero’s last great trial. But the story isn’t over quite yet – there’s still the third act.

Stage 9: The Prize

With a few exceptions, heroes don’t hunt down evil villains or complete difficult and dangerous challenges for fun (or at least not only for fun), they’re doing it to rescue the princess, claim the treasure, save the world, or fulfill some other personal goal or desire. Sometimes they legitimately claim their prize and other times they steal it or just get lucky, but either way it represents the reward for all their hard work and effort up to this point.

Depending on the hero and story, the prize and how the hero reacts after acquiring it will vary greatly. Many heroes celebrate after obtaining the prize or pause to think back on all the things they’ve been through to reach this point, perhaps achieving some form of understanding or enlightenment. But in some stories it turns out that the prize isn’t what they expected at all, which can lead to anger, grief, or disappointment.

However you choose to present it, this stage should be fairly short, and regardless of whether everything turns out the way the hero had hoped, it should provide the player with at least some measure of success and accomplishment.

Stage 10: The Road Home

With the prize in hand (whether literally or metaphorically, depending on what the prize actually is), it’s time for the hero to return home, either to the ordinary world where he or she started out or to a new home discovered during the journey. Some heroes choose to never return home, but the majority do, for one reason or another. Luke and Harry, for example, just wanted to live out peaceful lives free from the threats posed by their enemies. In other stories, the hero’s home may be in desperate need of the prize. Then there are some heroes like Zack, in CRISIS CORE – FINAL FANTASY VII, who merely want to see their friends and loved ones again.

In many stories, especially in video games, this stage is often quickly glossed over or even skipped entirely. Dragging it out too long can create an anticlimax, causing the story to end with a drawn-out whimper rather than a big bang. However, you can make good use of this stage as well. With the villain defeated and the prize in hand, returning home might seem to be an easy task, but that’s not always the case. In CRISIS CORE – FINAL FANTASY VII, Zack finds himself hunted by his former allies, leading to a very epic and emotional ending (which we’ll discuss in depth in Chapter 5). In this stage, it’s fairly common to see a new villain (who was, of course, secretly manipulating everything behind the scenes) emerge or a previously defeated foe make an unexpected return to cause one last bit of trouble for the hero. This can also be the place to work in a final plot twist or surprise, as in Shadow of the Colossus (which we’ll talk about in Chapter 4). Or, if you prefer a more clichéd event, the fortress, cave, space station, or other structure that the hero is in could start to collapse, because everyone knows that all evil lairs self-destruct shortly after their owner is defeated.

There really are a lot of things you can do with this stage; it all depends on what direction you want the story to go. It’s an opportunity to throw a final challenge in the hero’s path, give the hero one last chance to correct a mistake or realize an important truth, wrap up any remaining loose plot threads, or provide a shocking revelation that makes the hero and the player reexamine the events of the journey in a new light. These things don’t always have to happen on the road, though –they can also take place in the hero’s home itself as a final obstacle preventing him or her from returning to ordinary life.

Stage 11: The Return

At last the final stage of the story has been reached. The hero has returned, any last threats have been dealt with (unless you decided to save them as a sequel), and it’s time to bring the story to a close. For many, endings are the hardest part of any story to write. A good ending needs to tie up at least most of the major issues present in the story (with the exception of a cliff-hanger ending, which can best be thought of as a break in the middle of the journey rather than a true ending), show the hero’s ultimate fate, and provide a certain degree of closure and satisfaction to the player. There’s a fine degree of balance needed here. You want to tie up loose ends to avoid annoying the player with dropped plot threads and unanswered questions, but if you wrap everything up too neatly, the ending may seem cheesy or contrived. You also don’t want an ending that’s too short or abrupt, in which case players may feel cheated or disappointed because they weren’t able to really see things through to their full conclusion. Yet if you make an ending too long, it’ll drag and players will lose interest.

Some endings also contain an epilogue, giving the players a glimpse at what happens to the world and characters long after the ending proper. If done right, an epilogue can satisfy the player’s curiosity about the hero’s life after the adventure, help with the all-important sense of completion and closure, and/or help set things up for an eventual sequel. But if done poorly, an epilogue can drag or feel tacked on and unimportant.

Writing a good ending is something that can’t really be taught and is a challenge that even many of the most experienced writers struggle with. Ultimately, it’s less a skill to be acquired than it is an art form, something beautiful and complex that in the end you’ll have to discover for yourself. We’ll be talking about endings quite a lot over the course of this book and will examine the endings of many different games as well, so pay close attention to how those games handle their ending scenes and what did and didn’t work for them. If you can avoid the more common mistakes, you’ll at least be off to a good start.

I’ll Give It a Try Myself

I’ll relate my own personal experience with the structure. I had been hired by THQ to design an N64 role-playing game. Zelda had not come out yet, and Nintendo players were hungry for role-playing titles. I had recently come across Vogler’s explanation of the journey, and I devoured it. The assignment arrived, and I wanted to experiment with the structure (even though I, like many others, had written stories using the structure without truly knowing what it was). I copied out the main points of the story, used Campbell’s archetypes to populate the game, and cobbled together the structure and some basic thematic fantasy material from my own brain. I wrote a couple drafts and presented it to my assistant designer.

He liked it, and as he was a great writer, we riffed on the details a bit, especially the characters. The formal presentation at THQ was coming up in a couple of weeks, and we talked to their external producer on the phone. “I’m a big fan of RPGs,” he said. “I’d like the game to have as good a story as FINAL FANTASY VII.” I gulped.

“Great,” I replied. “I do too. We’re working on the story right now, and we’ll pitch it to you when we come to visit.”

The weeks passed, and we went to visit THQ. The development team sat around in a room and pitched the story to the two external producers and the VP of development. There were, in all, about fifteen people in the room. I got up in front of them and started into the story of Alaron and his journey to discover his magical self. I wove together all the beats from the journey, Meeting to Mentor to Crossing the Threshold to the Refusal of the Call, all told in very specific events in the story but (obviously) not making overt connections to the Hero’s Journey or Joseph Campbell in any way.

Twenty minutes later, when I got to the part about Alaron needing to die so as to be reborn, I became aware that no one in the room was making a sound. No one had coughed, or was checking their email, or was looking at their fingernails. They were listening to the story.

I got to the end, when Alaron ascends to the throne after defeating the lords of chaos after his rebirth, and the fourteen other people in the room stood up and gave me a standing ovation. My own dev team, THQ’s VP of production, my agent – everyone.

And at that moment I knew it wasn’t just my weeks of effort paying off so much as the power of the journey at work.

—Chris

It’s important to realize that you don’t have to follow the hero’s journey to the letter – nor should you. The hero’s journey is a set of guidelines, nothing more and nothing less. At times, it’s best to step outside those guides and go with what you think is best for your story. Feel free to add or subtract stages as needed or modify the existing stages and order to suit your story. If you think your story should start out in the middle of Stage 6, for example, with the events of the previous stages revealed via flashbacks, that’s fine. Although many good stories follow the hero’s journey pretty closely, many others veer wildly off course and still produce excellent results. Furthermore, the hero’s journey isn’t the only structure out there. If your story doesn’t seem to fit well within its confines, feel free to find another more appropriate structure or even create one of your own. After all, writing isn’t just about knowing the rules – it’s about knowing when to break them.

Case Study: Lunar Silver Star Harmony

Lunar Silver Star Harmony is the latest in a long line of ports and remakes of the Game Arts classic RPG Lunar: The Silver Star. It tells the story of a young boy named Alex who dreams of becoming a Dragonmaster and his friends as they journey across the land to save both the world and Alex’s childhood friend Luna from the clutches of the former hero turned villain, Ghaleon. Aside from its charming story, endearing characters, and frequently hilarious dialog, Lunar is also known for its challenging strategic battles (though the exact battle system changes a bit in each release). Both the Sega CD and PlayStation versions of Lunar have often been listed among best RPGs of their respective generations and have become popular collector’s items.

The story of Lunar follows the hero’s journey structure very closely. The following sections provide a breakdown of the plot, formatted to show how it fits within the structure.

Stage 1: The Ordinary World

Alex lives in the small, peaceful village of Burg with his talking pet Nall and his friends Luna and Remus. Though happy with his life, Alex often dreams of having adventures as did his hero, the legendary Dragonmaster Dyne, who is buried in Burg.

FIGURE 3.2

Alex, Nall, and Luna live a peaceful life. Lunar: Silver Star Harmony PSP © 1992 Game Arts/Toshiyuki Kubooka/Kei Shigema, © 1996 Kadokawa Shoten Publishing Co., Ltd./Game Arts/Jam, © 2009 Game Arts.

Stage 2: The Call to Adventure

While searching for treasure in a nearby cave, Alex and his friends encounter the dragon Quark. He senses potential in Alex and urges him to travel and seek out the other dragons so that he can complete their trials and become the new Dragonmaster.

Stage 3: Refusing the Call

Alex jumps at the chance to live out his dreams, as does Remus (who hopes to find his fortune in the city of Meribia), but Luna is unsure. Worried about Alex’s parents (who have raised her since she was a baby) and afraid to leave the place she’s lived all her life, she plans to return to Burg before reaching the city.

Stage 4: The Mentor

As they journey to the city, Alex’s group finds themselves surrounded by a large number of monsters when a powerful swordsman named Laike comes to their rescue. Although he doesn’t join the party, he and Alex have numerous run-ins throughout the game. Aside from his skills with a sword, Laike seems to know quite a lot about the dragons and acts as a mentor to Alex, preparing him to better face the challenges ahead.

FIGURE 3.3

Alex’s group runs into trouble and is saved by a passing swordsman. Lunar: Silver Star Harmony PSP © 1992 Game Arts /Toshiyuki Kubooka/Kei Shigema, © 1996 Kadokawa Shoten Publishing Co., Ltd./Game Arts/Jam, © 2009 Game Arts.

Stage 5: The First Threshold

The first threshold comes at the port town of Saith, where the group prepares to board a ship and leave their home island far behind. This is the point where Luna fully refuses the call and attempts to turn back (as mentioned in Stage 3).

FIGURE 3.4

Luna is reluctant to leave the island where she grew up. Lunar: Silver Star Harmony PSP © 1992 Game Arts /Toshiyuki Kubooka/Kei Shigema, © 1996 Kadokawa Shoten Publishing Co., Ltd./Game Arts/Jam, © 2009 Game Arts.

However, she’s stopped and reassured by Alex. Though still nervous, she follows him onto the boat and they set off, leaving everything they know behind and taking their first steps into the new world that awaits them.

Stage 6: The Journey

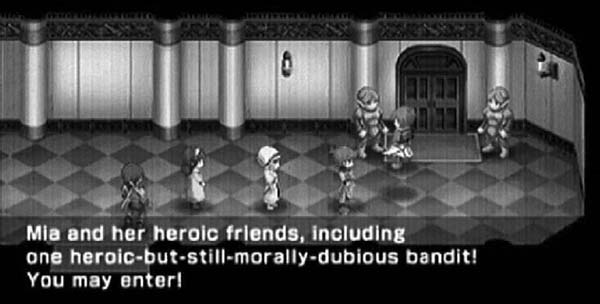

This stage constitutes the vast majority of the game and is when many important events take place. As Alex continues his quest to become a Dragonmaster, he parts ways with old friends when Remus decides to stay behind in Meribia, but meets many new friends and companions including the magicians Nash and Mia, the cleric Jessica, and the bandit Kyle. He makes enemies as well, in the form of the evil Magic Emperor and his top henchmen, a trio of powerful witches. Alex also suffers betrayal and loss when Ghaleon, the friend of his hero Dragonmaster Dyne, reveals himself to be the Magic Emperor, kills Quark, and kidnaps Luna. These events and several other big revelations make Alex’s quest much more personal as he begins seeking the power of the remaining dragons – not for fame and adventure, but to gain the strength he needs to stand up to Ghaleon and save Luna.

FIGURE 3.5

Alex and his new friends on their journey. Lunar: Silver Star Harmony PSP © 1992 Game Arts/Toshiyuki Kubooka/Kei Shigema, © 1996 Kadokawa Shoten Publishing Co., Ltd./Game Arts/Jam, © 2009 Game Arts.

Stage 7: The Final Dungeon

After gaining the power of the dragons and failing in their first attempt to infiltrate Ghaleon’s fortress, Alex and his friends regroup with the help of Laike and prepare for an all-out assault. Pressing on, they manage to fight their way to Ghaleon’s inner sanctum and defeat the last and strongest leader of his forces.

Stage 8: The Great Ordeal

Alex’s team faces Ghaleon, who tells them of his intentions to use Luna (who was previously revealed to be the reincarnation of the goddess Althena) to revive the goddess and gain her powers, becoming a god himself. With his plans nearly complete, he brings his full power to bear on Alex’s party, but after a long hard battle, he is defeated.

Stage 9: The Prize

With Ghaleon dead, the world is safe and Luna is free. At long last, Alex has achieved the things he fought so hard for.

Stage 10: The Road Home

Alex and his friends are ready to take Luna and return home, but it turns out that they were too late. The Luna that Alex knew and loved is gone, replaced by the reborn Althena. Unwilling to leave without her, Alex faces the angry goddess and –after barely escaping death at her hands – manages to awaken Luna’s memories and return her to her normal form.

FIGURE 3.6

Alex’s ocarina playing awakens Luna’s memories. Lunar: Silver Star Harmony PSP © 1992 Game Arts /Toshiyuki Kubooka/Kei Shigema, © 1996 Kadokawa Shoten Publishing Co., Ltd./Game Arts/Jam, © 2009 Game Arts.

Stage 11: The Return

Now that everything has been set right, Alex, Luna, and their friends return to their peaceful life at home.

As you can see, Lunar’s story is a near-perfect fit for the hero’s journey, making full use of every stage. The only particularly notable deviation is in Stage 3, in which it’s the hero’s companion (Luna) and not the hero himself (Alex) who resists the call. But despite its strict adherence to the structure, Lunar avoids many of the clichés that often plague hero’s journey stories. The mentor (Laike), for example, doesn’t sacrifice himself and manages to survive the entire adventure. And Alex’s near death (or actual death, if the player isn’t careful) at the hands of Althena after Ghaleon has been defeated comes as quite the surprise to most first-time players. Twists like these and the enduring popularity of the story (as evidenced by Lunar’s many ports and remakes) go to show that even though it’s been around since the earliest myths and legends, the hero’s journey can still be used to create interesting and enjoyable stories even in new mediums like video games.

FIGURE 3.7

Alex and Luna together again in Burg. Lunar: Silver Star Harmony PSP © 1992 Game Arts/Toshiyuki Kubooka/Kei Shigema, © 1996 Kadokawa Shoten Publishing Co., Ltd./Game Arts/Jam, © 2009 Game Arts.

Common Themes and Clichés in Game Storytelling

As any gamer can tell you, there are certain themes and clichés that have a tendency to pop up in what can seem like at least every other game. But this is by no means a phenomenon unique to video games. Fantasy novels, sitcoms, Hollywood action movies, and just about every other story type or genre you can think of comes complete with its own set of clichés. Whether such clichés are good or bad is a matter of debate (and something we’ll discuss further a little later on), but either way, they’re a firmly ingrained part of storytelling and one that’s unlikely to ever disappear, so it’s important to be familiar with them.

Like all forms of storytelling, video games have a laundry list of common, clichéd characters and scenarios. Some are glaringly obvious and others are more subtle, but it’s hard to find a game that doesn’t make use of at least one or two of them. A complete list of game clichés would be extremely long (a quick Google search can easily turn up hundreds of them) and many are related to the gameplay, not the story (like how everyone leaves exploding barrels lying around and then decides that they’d make excellent cover during a gun fight), and are therefore something for designers, not writers, to worry about, but the following list covers a few of the most prevalent story-based clichés in gaming.

The Amnesiac Hero

Soap opera heroines aren’t the only fictional characters who seem to develop amnesia at the drop of a hat; it’s quite common for a game’s main character and/or the occasional party member to start out with a bad case of amnesia. This cliché seems to be especially popular in RPGs, a fad most likely caused by the Square Enix’s tendency to feature amnesiac heroes in their genre-leading FINAL FANTASY series.

So what’s the point? Well, when it comes to video games, amnesia makes for a very convenient plot device. Most newer games, for example, and many older ones as well, start out with a tutorial section designed to help players (especially those who haven’t read the instruction manual) get used to the controls and gameplay. On the surface, this sounds like an excellent idea (which is made even more excellent when said tutorials can be skipped by more experienced players). But from a story perspective, there’s a problem. Although it makes sense that a fresh-faced kid from a farming village could use some serious training before heading out to battle, it’s difficult to explain why your veteran adventurer or hardened space marine suddenly needs to be told how to move and fight … unless he or she has amnesia. It also provides a good excuse for the hero’s friends to constantly point out details about the world and/or the hero’s past, all things that the player needs to know but the hero him- or herself, without amnesia, wouldn’t need to be reminded of. Then, of course, it can also set the stage for a big reveal when the hero regains his memories and discovers that he’s really not Bill the Legendary Space Marine but a fruit vendor who just happens to look like him.

Of course, amnesia has many legitimate and nonclichéd uses in storytelling as well. It can make for some interesting character development, especially if the hero, after regaining his or her memories, realizes that his or her past beliefs and allegiances were far different than they are now. It also helps if the amnesia fits well with the rest of the plot and wasn’t just caused by a random bump on the head so that the hero would need to learn how to swing a sword all over again.

FINAL FANTASY VII, though probably partly responsible for the amnesia fad, uses an extremely interesting and unconventional take on the amnesiac hero. In fact, for the first two-thirds of the game, you don’t even realize that the hero, Cloud, has amnesia at all. Therefore, it comes as quite a shock when it’s revealed that many of his memories are, in fact, a twisted mixture of fact and fiction created by his mind when his original memories were lost. Many fans, myself included, consider the point where he at last pieces together his real memories and discovers the truth about certain past events to be one of the highlights of the story.

A Powerful Tool in Your Belt

One of the most powerful tools in dramatic storytelling is the Major Dramatic Question, or MDQ. This question is created in the mind of the audience the moment the hero accepts the journey, and is a form of the question “Will the hero succeed?” Will Luke avenge his aunt and uncle? Will Frodo throw the ring into Mount Doom? Will Indiana Jones find the Ark? It is the nature of our storytelling curiosity that we, the audience, stick around until the end of a story in order to see how it all comes out. The instant we get the answer to the dramatic question, all the energy drains out of the story for us and we want to move on, head to the parking lot to find our car, check our cell phone, and so on. It is a saying in theater that as soon as the question is answered, you’ve got maybe five minutes, max, until the audience gets so antsy that they stop paying attention. The clearer you can state the MDQ of a story for yourself and the more clearly you can implant that question in the mind of the audience, the better chance you have of keeping their interest until the very end. We’ve all been to movies where we said, “When will this end?” Often, when you deconstruct those stories, you will find that either the MDQ is unclear or that the MDQ stated at the beginning of the film was answered ten minutes ago and we’re still hanging around watching something else unfold.

—Chris

The Evil Vizier/Minister/Aide/Lackey

It’s no secret that betrayal makes for a great plot twist (and a convenient way to bring all the hero’s plans crashing to the ground halfway through the game), and if the betrayer is a person in a position of power, he or she can really do some damage when finally revealing his or her true allegiances. Unfortunately, after being betrayed by just about every vizier, general’s aide, and king’s minister, the usual player reaction to such a “shocking” plot twist isn’t so much “I can’t believe it!” as “Duh – they should have figured that out ten hours ago.” On that note, after the vizier, the hero’s best friend is the second most clichéd person to betray him.

Betrayal can still make for a very good plot twist, but it’s best to make the betrayer a less obvious choice, or at the very least, not give the vizier an evil haircut and script full of suspicious one-liners. Even better, take advantage of the cliché and make the seemingly evil vizier a good guy to draw the player’s attention away from the real enemy agent.

No One Noticing the Evil Vizier/Minister/Aide/Lackey

Of course, the goal of being a spy or traitor is to play your role so well that no one realizes your true allegiances. In many video games, however, the evil vizier or other character who is plotting to betray the heroes usually does such a poor job of hiding his or her intentions that it seems ridiculous that none of the heroes have figured out that he or she really isn’t on their side. As noted earlier, the future betrayer really shouldn’t look, act, or talk like a villain. If most players realize the vizier is evil long before the heroes do (and the players aren’t privy to any extra information unknown to the heroes), you have a problem.

The Last of His Race

Having a hero who is the last survivor of his clan, race, family, village, or so on gives the hero a good excuse to go after the villain (someone had to have killed off everyone else, of course) and is also a convenient way to explain why the hero has special powers that nobody else does and is the only person who can possibly save the world. Though overused, this cliché usually doesn’t seem to bother people as much as some of the others do.

I Am Your Father

Whether or not the hero is the last of a dying race, it’s quite common for the hero’s father or other close relation (brother being the second-most clichéd) to be either the main villain, a high-ranking follower of the main villain, or, in some cases, a legendary hero who once opposed the main villain (and probably isn’t as dead as everyone thinks). Like most clichéd plot twists, it can actually be done very well if handled correctly, but it’s hard to avoid either giving away the surprise too early or having too little foreshadowing, making the eventual “I am your father” moment seem sudden and random.

A Party of Clichés

The hero’s friends, allies, and/or party members often include several of the following characters: a beautiful mysterious girl (often the last of her race) who holds the key to either saving or destroying the world and will eventually get kidnapped; a rebellious princess (sometimes combined with the mysterious girl); a gruff, tough-as-nails warrior girl (who will eventually soften up and fall in love with the hero); a grizzled, battle-hardened warrior who is actually (or eventually becomes) a really nice, friendly guy; an unemotional or emo character who slowly learns to open his heart and trust others; and a cute creature (often the last of its race) who is pretty useless in battle but hangs around for comic relief. Although these basic character setups work quite well in humorous stories, in a more serious tale they should ideally be avoided or have a lot more depth to them than is first apparent. We’ll talk more about creating good characters in Chapters 4 and 5 –for now, just keep these clichés in mind.

Saving the World from Evil

Regardless of the original goals and accomplishments on the game’s journey, the hero and his or her friends will almost always end up having to save the world. Quite often, the threat to the world comes from an ancient evil that was either recently revived (often by a misguided villain or hero) as in Arc the Lad or that just likes to stop by and destroy everyone every thousand years or so like in Mass Effect.

Of course, saving the world or universe is far more impressive and epic than just about any other possible goal and brings a definite sense of accomplishment to the player. But it’s important to remember that it’s still perfectly possible to tell a good story in which the heroes have far less lofty goals, such as in THE WORLD ENDS WITH YOU, Shadow of the Colossus, and FRONT MISSION 3 (all of which are covered in detail in other chapters).

The Ancient Civilization

One last common game cliché is the ancient civilization. Said civilization was usually made up of beings with highly advanced technology or magic (far more so than anyone in the modern day world) and was mysteriously wiped out long ago, leaving nothing but ruins and artifacts. Such a setup adds a bit of mystery to a story and allows you to toss in otherwise inappropriate technology wherever it’s convenient.

Unfortunately, what happens next has become very predictable. Either the hero or the mysterious girl is usually the last of the ancient race and the villain is either the one who destroyed said race in the first place or is foolishly trying to resurrect the monster or technology that did. This cliché has formed the basic backstory for many excellent games, but is still one that you should try to avoid when possible.

If you’ve played a lot of games, you probably found yourself nodding your head and maybe even chuckling a bit as you read over the previous list. They’re all elements that are used in many games – even ones that are known for their excellent stories. So why are these clichés used and reused so often? First off, they’re popular. Nearly every big cliché got its start in a very popular game, book, or movie and, since it worked so well before, other writers decided that it would probably work well again, and again, and again, and again, until it eventually became over-used enough to be deemed a cliché. Second, clichés provide something familiar for the players to identify with. Sure, all gamers know that the grizzled warrior and mysterious girl are clichéd characters, but they’re also familiar with (and quite likely fond of) incarnations of those characters in other games and have a basic idea of what to expect from them, which can actually help raise many players’ interest in the story (at least early on). And, finally, clichés simply work well. They may be overused and predictable, but they got that way for a reason. In the hands of a good writer, clichés can be used to create excellent characters and plot elements. However, if mishandled, they’ll make a plot feel generic, corny, and generally uninspired.

When to Use and When to Avoid Story Clichés

When using clichés, keep in mind the following rules.

Rule 1

Try to limit how many clichés you use in a single game. Most players probably won’t mind if you make use of one or two clichés from the previous list, but if you use all of them, you’re probably asking for trouble (unless you’re either a really amazing writer or making fun of those clichés in a humorous story).

Rule 2

Make the clichés feel different and new. With a bit of clever writing, you can twist clichés around to make them more interesting. For example, maybe the mysterious girl is really just an ordinary orphan and the ancient civilization was destroyed in a natural disaster instead of by an evil force or super weapon. There’s no reason you can’t take part of a cliché and change the rest to something different and new.

Rule 3

Use clichés to mislead the player. Because clichés are so overused, most players can quickly pick them out and predict what’s going to happen next, so why not use this against them? You could have an evil-looking but actually good vizier draw the player’s attention away from the true spy or really play up the mysterious girl only to reveal that the key to saving the world actually lies in a much more ordinary character instead. With a bit of imagination and a good setup, you can use clichés to keep players guessing for the entire story.

Rule 4

Don’t use clichés for the sake of using clichés. Because clichés are based on popular story elements, it’s not uncommon for novice writers to smash as many of them as possible into their stories, using them almost like a checklist. This is, of course, a very bad idea. If you truly feel that the story you’re writing has need of a cliché element, go ahead and use it. If you do it right, the players won’t mind. But, if you start adding in unnecessary amnesia, clichéd character types, and ancient civilizations, the story will seem forced and, of course, cliché.

Case Study: Arc the Lad

| Developer: | Sony |

| Publisher: | Working Designs |

| Writer: | Kou Satou |

| System: | Sony PlayStation |

| Release Date: | April 18, 2002 (US), November 23, 2010 (Playstation Network rerelease) |

| Genre: | Strategy RPG |

Arc the Lad is the first in a series of strategy RPGs created by Sony. Although the first game was released in 1995 in Japan, it wasn’t until 2002 that it came to the United States as part of a collection containing the first three games in the series, along with a large number of extras and bonus items. The first two games, Arc the Lad and Arc the Lad II (which we’ll talk about more in Chapter 7), act as a set, with the first game serving as more of a prologue than a full story and the sequel picking up shortly after it ends. Although the first portion of Arc the Lad II focuses on a different set of characters, they eventually join Arc with the others from the first game to continue the original quest. Players are even given the option to import their saved data from the first Arc the Lad, which allows the original heroes to transfer their levels, equipment, and items into the second game.

The plot revolves around a boy named Arc and his companions as they struggle to stop the leader of Romalia from using the power of an ancient evil known as the Dark One to command armies of monsters and further the expansion of his empire.

Although Arc’s story does get pretty interesting – especially in the second game, in which nearly every character in his large party (which eventually grows to include a mysterious girl, rebellious princess, grizzled warrior, unemotional character, and cute thing, among others) has his or her own detailed backstory and set of side-quests – the first game (and, to a lesser extent, the second) makes heavy use of clichés.

To start, Arc’s father was a hero who fought against the Dark One (a vaguely defined evil force that destroyed an ancient civilization) only to go missing and is, as it turns out, not dead like everyone thought he was. Arc’s first companion in his quest is Kukuru, a beautiful girl who is the last of her clan of shrine guardians who protect the Dark One’s seal (or at least the last person in her clan who is still doing her job). And that’s just the beginning. It turns out that the king of their country, whom Arc and Kukuru meet shortly after (and who later reveals that he is Arc’s uncle), is being served by an evil minister no one realizes is evil and later betrays them all. To top it off, he’s only the first of several high-ranking figures who also turn out to be monsters in disguise and to betray the party over the course of their adventure.

In the end, despite its reliance on clichés, Arc the Lad still managed to tell a fairly good story (particularly when combined with Arc the Lad II) and proved to be a fairly popular title, especially in Japan. In fact, most complaints about Arc the Lad’s storyline are centered around the second game’s ending, rather than the overabundant clichés.

Storytelling is a complex art, and the parts of a story that come naturally to one writer may be extremely difficult for another. Games provide many advantages for storytellers, including their audiovisual presentation, length, and interactivity, but also come with their own set of challenges and problems. Sticking with types of stories that support large amounts of fighting, puzzle solving, or other common gameplay elements can make writing for games much easier, as can following tried-and-true narrative structures such as the hero’s journey. But that doesn’t mean you have to do either one. With the right idea and careful planning, there’s no limit to the types of stories that can be told in games.

Another issue to be aware of is clichéd story elements that have been heavily overused, such as the evil vizier and highly advanced ancient civilization. Though these clichés can still be used, and can in fact make for some excellent plot twists and character development opportunities if done correctly, you need to be careful about the way you use them if you want to avoid having your story come across as generic and predictable.

1. When writing a story, what parts do you have the easiest time with? What parts are the most difficult?

2. List some video games you’ve played which used nonideal story types. Did the writers and designers succeed in turning the stories into enjoyable games? Why or why not?

3. Take a look at the story from one of your favorite games, break it into stages, and see how well it fits within the hero’s journey structure.

4. Choose a game you’ve played recently and make a list of all its clichés. Feel free to list clichés that weren’t discussed in this chapter.

5. Think of a game that used a cliché in a very different and unexpected way. How did the writer change the cliché to accomplish this?