CHAPTER

Fourteen

What Players Really Want: The Most Important Issue

As you’ve seen in the last two chapters, good arguments can be made for the supremacy of both player-driven and traditional storytelling methods in games. It’s quite likely that you have your own thoughts on which side makes the better case. When I first began researching this subject, I found myself more in line with the pro–traditional storytelling group, but I also saw that both sides based many of their key arguments on assumptions of what players wanted and enjoyed most in stories (freedom and control vs. a structured and well-told story). The problem was that although everyone was saying “players want this” or “players want that,” as far as I could tell, no one had done any serious research into what players actually wanted – the respondents were just going off their own personal opinions. And although voicing your own opinions is fine, it’s rather rash and even a little arrogant to automatically assume that the majority of game players agree with your opinion, no matter how important of a position you do or don’t hold within the game industry. With that in mind, I decided that the only way to truly answer the question of which type of storytelling was better was to ask the players themselves, so I put aside my own opinions and set out to find what players really want.

The Debate Continues

One of the most well-known figures in the debate is Raph Koster, designer of Star Wars:Galaxies as well as having worked extensively on Ultima: Online. Raph’s bona fides in this area of game design are beyond question, and he is famous (or infamous, if you will) in this debate: in fact, he issued a challenge to designers in the form of this quote: “Designers, get over yourselves!”1

Here’s the larger story from that article: “At the 2002 Game Developer’s Conference, an audience member asked the panel on ‘Building the Next-Generation PW’ how he, as a writer, could ensure the integrity of his story in a PW. The reply came from panel member Raph Koster, the creative director on Star Wars Galaxies and former lead designer of UO: ‘Get over yourselves; the rest of the world is coming. Okay? People value self-expression. Is ‘story’ going to go away? No. Is careful crafting going to go away? No. Are the professionals engaged in that going to go away? No. Well, except that IP—the concept of intellectual property—may, but that’s a whole other side discussion. The thing is that people want to express themselves and they don’t really care that 99 percent of everything is crap, because they are positive that the 1 percent they made isn’t. Okay? And fundamentally, they get ecstatic as soon as five people see it, right?’”

Powerful stuff, and very true (at least in my experience with this community, it is true). In my industry jobs as well as in my role as an educator, I have observed this phenomena again and again, which I explain this way: there is a fundamental difference between those who have been paid by a publishing organization (which I define as a book publisher, movie studio, television network, or game publisher) to create stories and those who create stories for themselves and their close acquaintances. Many, many people think they can write creatively, and they certainly can. Do a Google search on “fan fiction” if you want to scare yourself a little bit. Almost every member of the Internet population can write creatively, and, generally speaking, they don’t see much difference in quality between what they can and do create for themselves on the side in their spare time and what those making a living doing so can produce. It has been said by wiser people than myself that “Everyone has one novel in them, but the real test is whether you can actually finish that novel, and, having done so, what you then do for an encore.” The real difference lies in craft, and writing for a larger audience, and being asked to write more stories. But because the skills come so easily to most computer-literate people (as one game producer said to my writing staff one dark and evil day, “What’s so hard about it? All you have to do is type!” and yes, he was serious), the very, very difficult issue of what and how to write so as to achieve true intrinsic worth (to avoid being categorized in the “99 percent crap” bucket, as so eloquently phrased by Mr. Koster) is often ignored in the blush of false praise heaped upon young authors by their friends and social network.

Writing for quality over and over in such a manner that people will pay to consume more of that writing is a very rare skill – a skill that Hollywood (to name but one funding source) pays top dollar to acquire. But the desire to have others see one’s writing is very attractive, and the belief (as Mr. Koster stated) that one’s writing is good is pervasive amongst the crowd of people that play games (at least it feels that way to me). Perhaps the cause rests in the observations of Henry Jenkins about the Web 2.0 generation; perhaps it lies in the easy self-publishing methods and the removal of traditional gatekeepers. I don’t truly know. But what I do know is the evidence is in that the current generation of gamers want this type of media to respond to their desires, and they want this media to hear them. But, as we will delve into shortly, in what way do they want to be heard?

—Chris

1Rather than take it out of context, I’d like to give it full attribution: Mulligan, Jessica and Bridgette Patrovsky, Developing Online Games: An Insider’s Guide (New Riders, 2003), pp. 145–146. ISBN 1592730000.

Do Players Know What They Really Want?

In the previous chapter, we talked about how giving players control of a story can actually lead to them unwittingly turning the story down a less enjoyable path, no matter how hard they try to create the best possible outcome. The example of a player-driven slasher story showed that often the “best” choice in a given situation doesn’t lead to the most interesting or entertaining story. This brought me to an interesting question. Do players who say they want games with highly player-driven stories actually end up enjoying them more than games with more traditional stories? Perhaps, even if they like the idea of player-driven storytelling, they might unconsciously prefer more traditionally structured stories. For example, let’s say we have a person who says that he thinks FPS is the best game genre there is. However, upon questioning him a bit further, we discover that his three favorite games of all time are RPGs. That’s quite a big disconnect there. If he thinks FPS games are so amazing, shouldn’t they dominate his top three list? This inconsistency suggests that although our subject may really like the style and concept of FPS games, he actually gets more enjoyment playing RPGs and therefore prefers them, albeit subconsciously.

Clearly, my research wouldn’t be complete unless I checked whether players’ stated storytelling preferences matched up with their actual ones. I was also very curious to see whether a large number of players demonstrated this type of mental disconnect or if I was merely overthinking things. Therefore, the question of whether players really know what they want became an important one as I continued to plan out my research methods.

I decided that the simplest way to discover what types of stories players liked best was to ask them. To that end, I created and ran my first research survey in the summer of 2009. The survey focused on players’ storytelling preferences in games, books, and movies and also contained questions designed to determine whether the players’ stated preferences matched their actual ones. The results of that survey became an important part of my master’s thesis, which laid much of the groundwork for this book. Though the results of that survey shed a considerable amount of light on what types of stories players enjoyed most and the stated vs. actual preference divide, it failed to consider how those preferences affected which games players buy. So in the summer of 2010, while writing Interactive Storytelling for Video Games, I conducted a second survey, this time focusing on how stories influence game purchasing decisions.

Both surveys were conducted using a targeted random sample of North American game players and can be considered a statistically valid and accurate representation of the opinions of American and Canadian gamers. We’ll be covering the key findings and their implications here, but if you’d like more detailed information about the surveys’ content and results, you can find it on this book’s companion website, http://www.StorytellingForGames.com.

How Important Are Game Stories to Players?

The first thing the survey showed was that most players pay attention to and care about game stories. Nearly 70 percent of respondents said that they tend to pay close attention to dialog and cut-scenes in games. In contrast, fewer than 10 percent reported that they pay little or no attention. Furthermore, in their write-in comments, a large number of respondents said that their interest in and/or enjoyment of a game’s story is the key factor when deciding whether to finish and/or replay most games. Clearly, the stories in games do matter.

We All Want to Know Why They Play

When we polled players in the Earth and Beyond audience during the game’s live existence, we discovered that even in our MMO, more than 66 percent of the player base were aware of the ongoing story changes, even if they themselves hadn’t actually partaken in the “story missions” we were delivering to the audience in our updates. If they hadn’t actually played the missions, they had discovered the story changes by talking to fellow players or by spending time on player-created websites. This number surprised even the writing staff, as we had no idea that our story was penetrating so deep within our audience. We had not even come up with WoW’s brilliant idea of linking level advancement to completing every quest.

—Chris

That’s not necessarily to say that story is more important than gameplay (opinions on that matter were rather evenly divided), but even most respondents who put gameplay above story were quick to point out just how much a good story adds to a game. It should be noted, however, that although respondents loved games with great stories and were generally okay with games that have no stories at all (provided that they enjoyed the gameplay), they were quick to point out that an uninteresting or poorly told story can easily ruin an otherwise good game. This further discounts the old notion that the story is a relatively unimportant game element that can be thrown together at the very end of the design process.

One last issue that came to light when studying the importance of game stories was that of demographics. With women accounting for more than 25 percent of respondents, and ages ranging from 13 to 60 across both genders, the surveys cover a very wide variety of gamers. Though, unsurprisingly, the “average” respondents were males in their late teens to mid twenties. Interestingly enough, there were no significant differences in storytelling preferences between respondents of different ages or genders. Although this goes against the common perception that men and women like different types of stories, it just goes to show something many writers have known for a long time: a good story can appeal to anyone, man, woman, or child. Of course, that doesn’t mean that everyone will like any given story, no matter how good it may be, but it implies that individual likes and dislikes are based more on each player’s personal preferences than age or gender.

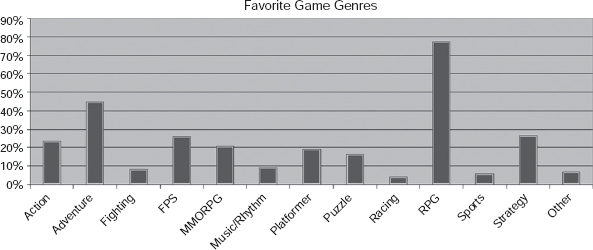

When asked to choose their three favorite genres of games, respondents listed games as shown in Figure 14.1 (averaged across both surveys).

Note that RPGs and adventure games, which are traditionally well known for their stories, are the most popular genres by far, and that fighting, sports, racing, and music games, which typically have little to no story, are the only mainstream genres to score less than 10 percent. Though gameplay preferences no doubt play a significant role in this breakdown, it backs up respondents’ statements about the importance of stories in games. There’s no other way to fully account for the massive gap between genres known for story-based games and those that focus almost exclusively on gameplay.

Respondents’ top three favorite game genres.

Story Preferences by the Numbers

When asked directly which types of stories they preferred in games (show in Figure 14.2), 30 percent voted in favor of interactive traditional stories, 24 percent for multiple-ending stories, 20.5 percent for branching path stories, 6 percent for highly player-driven styles such as open-ended and fully player-driven stories, and 4.5 percent for no story at all. Most of the remaining 15 percent stated that as long as the story is well done, they have no real preference.

FIGURE 14.2

Respondents’ preferred storytelling styles. Key: Interactive Traditional Stories (ITS), Multiple-Ending Stories (MES), Branching Path Stories (BPS), Highly Player-Driven Stories (HPDS), No Story (NS), No Preference (NP).

As you can see, interactive traditional stories – which are the most structured and least player-driven style – were the most popular answer, although multiple-ending and branching path stories score fairly high as well. Highly player-driven stories, however, scored extremely low among respondents, which casts a considerable amount of doubt on the argument that what players want most from stories is to take control and shape the plot to their own preferences. If this were true, highly player-driven stories would have a much higher rating. Although many respondents clearly like to have some control (as evidenced by the popularity of multiple-ending and branching path stories), they don’t want to sacrifice a well-structured and well-paced story to get it.

When discussing what attracted them most to specific stories, respondents cited a variety of different factors, with the majority choosing either the characters or the setting. The overall plot was less of a concern, though in many games the characters and/or setting are tied so tightly into the main plot that it can be virtually impossible to separate them. Games such as FINAL FANTASY XIII and Heavy Rain contain perfect examples of highly character centric stories; The Elder Scrolls III: Morrowind and Bioshock stories are heavily tied into their settings. Many respondents also noted that particularly unusual or unique settings or story premises often pique their initial interest in a game, though their continued interest is entirely dependent on a combination of the gameplay and how the story plays out as the game progresses.

The next question to ask is whether those are really the types of stories that players most enjoy. If the respondents’ actual preferences match up closely with their stated preferences, then the answer would be clear, but if there’s a large disconnect between the two, it would strongly suggest that many players may not fully understand which types of stories they want and enjoy most.

The Best Game Stories

To try to solve this mystery, I asked my survey participants to name three games that they felt had exceptionally good stories. This yielded a list of 223 unique entries that included 199 games and 24 series (note that specific games from some of those series were also listed and are part of the 199). A complete list of these games and series can be found in Appendix B of this book. A breakdown of the storytelling styles used is shown in Figure 14.3, which focuses on only the 223 unique entries in the list. Figure 14.4 also accounts for how many respondents mentioned each specific game.

Note that six of those games (with one nomination each) were extremely obscure and I was unable to find enough information about them to identify their storytelling styles. Their storytelling style is listed as “unsure” in the charts and appendix. An additional four games (one of which received two nominations) are marked as not applicable, as three of them are board games (or digital re-creations thereof) and one is a tabletop RPG.

Respondents’ best game stories (unique games). Key: Interactive Traditional Story (ITS), Multiple-Ending Story (MES), Branching Path Story (BPS), Open-Ended Story (OES), Fully Player-Driven Story (FPDS), No Story (NS), Not Applicable (NA), Unsure (U).

FIGURE 14.4

Respondents’ best game stories (all nominations).

Surprisingly enough, the difference between the two graphs is minimal, with the percentages for most storytelling styles varying by only one or two percentage points. But, more importantly, these graphs show significant differences when compared to the chart of the respondents’ stated preferences. First, it’s clear that interactive traditional stories are still the most popular. However, though only 30 percent of respondents listed interactive traditional storytelling as their favorite style, more than 61 percent of the listed games have interactive traditional stories. In stark contrast to the massive jump in popularity experienced by interactive traditional stories, multiple-ending stories and branching path stories, both of which were the stated preference of more than 20 percent of respondents, dropped significantly. Multiple-ending stories fell from 24 percent to 13 percent in the first chart and 16 percent in the second. Branching path stories faired even worse, dropping from 20.5 percent to 5 percent and 7 percent. Open-ended stories scored 8 percent and 9 percent, showing a slight improvement, but fully player-driven stories received only 4 percent and 2 percent, putting them on the same level as games without stories.

As a note, the five games most frequently listed by respondents were

1. FINAL FANTASY VII (interactive traditional story)

2. CHRONO TRIGGER (multiple-ending story)

3. XENOGEARS (interactive traditional story)

4. & 5. (a tie) FINAL FANTASY X (interactive traditional story) and Mass Effect (multiple-ending story)

So what does all of this mean? First, it shows that interactive traditional storytelling is the most popular game storytelling style among players, reflected by both their stated preferences and their favorite game stories. Second, in general, the more playerdriven the storytelling style, the less popular it is among players. And although some types of player-driven storytelling – specifically, multiple-ending and branching path – proved to be moderately popular, it was extremely rare for players to list games using either style as having exceptionally good stories. Therefore, games using interactive traditional stories are not only the most popular among players, but are also the most likely by far to contain stories that players really enjoy.

So does this put an end to the debate? Maybe not entirely. When we take players’ stated preferences into account, it’s clear that a lot of them do like the idea behind multiple-ending and branching path stories, even though game stories using those styles rarely stack up to those using interactive traditional storytelling.

This seems to indicate that although many gamers do feel as if they want some control (though not an excessive amount) over the stories in their video games, they actually get more enjoyment out of well-structured stories, which provide them with a strong illusion of control instead. This result seems to indicate that traditional storytelling methods are superior.

However, it could be argued that the reason for these findings is that games using highly player-driven forms of storytelling are still relatively new and that players will come to enjoy them more as they become better accustomed to the style. You could also attempt to explain player-driven storytelling’s lack of popularity by blaming the immaturity of the style itself, and say that it won’t come into its true potential and gain the recognition it deserves until designers and writers become more experienced and skilled creating highly player-driven stories.

We Have to Find Our Own Way

Or you could say that it’s just much, much harder to find a way to craft those kinds of stories in such a way as to make them as compelling as more traditional structures.

—Chris

It’s quite possible that there’s some truth to both of those claims. However, I can’t imagine them accounting for the entirety of the massive gap in popularity found in the list of respondents’ best game stories. If the second chart (the one that tracks how many times each game was listed by respondents) showed a significant increase in the popularity of games using highly player-driven stories when compared to the first chart, I’d be more inclined to agree, especially as there are far more games available which use traditional storytelling methods. But the fact that both charts are nearly identical shows that’s not the case.

My first survey answered the question of which storytelling styles gamers prefer and enjoy the most, but the differences between their stated preferences and their actual preferences (as determined by their favorite game stories) made me wonder which of those two sets of preferences most affected which games they purchased. After all, game development is a business. Unfortunate as it may seem, whether or not people enjoy a game is often far less important than how many people buy that game to begin with. This is made quite clear by looking at games based on popular licenses (such as movies or TV shows), a good many of which receive strong sales despite rather abysmal reviews. So the fact that gamers tend to most enjoy games with interactive traditional stories would be far less important if they’re more likely to buy games with highly player-driven forms of storytelling – assuming that stories play a significant role in the average gamer’s purchasing decisions in the first place.

To solve this final puzzle, I focused my second survey on determining two things: what role, if any, story plays in deciding which games to buy, and whether gamers are more likely to buy games that use player-driven forms of storytelling.

Buying Habits by the Numbers

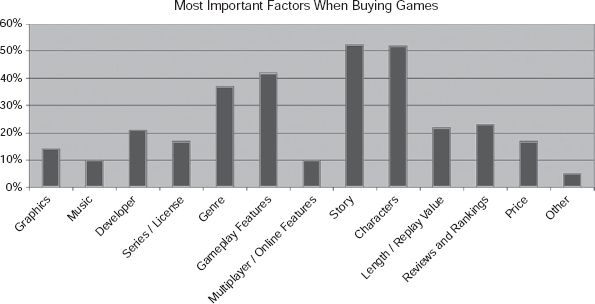

The first thing to establish was how large of a role stories have in which games people buy (Figure 14.5).

When asked to list the three most important factors when deciding whether to buy a game, more than 52 percent choose story, making it the most frequently chosen option over gameplay features (42 percent) and genre (37 percent). Further-more, 40 percent of respondents said that they frequently buy games primarily for their story, 45 percent said they do so occasionally, and less than 14 percent said that they rarely or never do so.

Although this shows that stories do significantly affect which games players buy, it’s not quite that simple. In their write-in answers, many respondents noted how difficult it can be to get a good feel for what a game’s story is like before purchase. Some dealt with this problem by focusing on games that seemed to have particularly unique and interesting settings or characters; others choose games based on what they heard about the story from friends or read in reviews. However, the majority of respondents said that they tended to focus primarily on games by certain developers that they already knew – through personal experience – made games with excellent stories (such as Square Enix and Bioware).

FIGURE 14.5

Respondents’ most important factors when buying games.

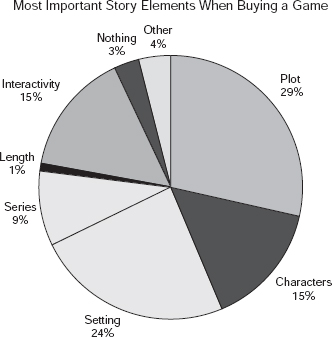

As you can see in Figure 14.6, the majority of respondents specified the overall plot as the most important part of a story (28.5 percent), ahead of setting (24 percent), characters (15 percent), and interactivity (15 percent). Interestingly, series ranked fairly low, which could indicate that although many players look to specific developers and series in order to find good stories, they care much more about the quality of the story itself than they do about the series or brand.

At 15 percent, the interactivity score isn’t amazing, but it does manage to tie characters for third place, so its impact on sales certainly can’t be discounted. Furthermore, nearly 50 percent of respondents said that a high level of interactivity and freedom makes them more likely to buy a game. Of the remaining 50 percent, most don’t care one way or the other (45 percent), and the remaining few (5 percent) say that a high degree of freedom makes them less likely to purchase a game. This seems to make player-driven storytelling a decent selling point, though it would likely need to be combined with other more important elements such as a strong plot (as evidenced by a respected brand and/or good reviews), an interesting setting, and good gameplay in order to make a significant impact on sales.

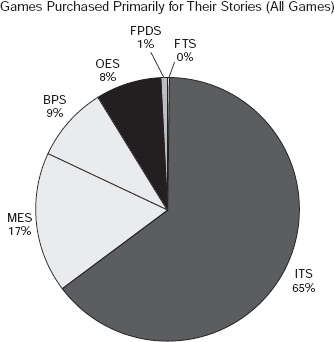

However, because I had already shown that players’ stated preferences didn’t always match their actual preferences, I wanted to see just how closely their stated preferences and game purchasing habits matched up. To do so, respondents were asked to list three games that they had purchased primarily for their story. The final list contained 191 unique entries composed of 174 games and 17 series (note that specific games from some of those series were also listed and are part of the 174). It’s important to keep in mind that respondents were questioned only about which games they bought primarily for their stories, not how much they ended up enjoying those stories later on. Figures 14.7 and 14.8 break down the storytelling styles used in those games. Note that Figure 14.7 focuses only on the 191 unique entries in the list and Figure 14.8 also accounts for how many respondents mentioned each specific game.

FIGURE 14.6

Respondents’ most important story elements.

As you can see, despite the fact that 50 percent of respondents said that a highly player-driven story would make them more likely to purchase a game, games using interactive traditional storytelling still dominate when we look at both unique games and all nominations (71 percent and 65 percent, respectively) with multiple-ending stories remaining a very distant second (12 percent and 17 percent). Branching path stories did do slightly better than in the best game stories list (8 percent and 9 percent), primarily due to Heavy Rain and Mass Effect 2 (both of which were released in early 2010, several months after the completion of my first survey). Once again, open-ended stories (6 percent and 8 percent) and fully player-driven stories (2 percent and 1 percent) scored very low. Interestingly enough, the list also contained a single fully traditional story, Umineko no Naku Koro ni (When Seagulls Cry), a Japanese visual novel by 07th Expansion, the same team behind Higursahi When They Cry.

FIGURE 14.7

Respondents’ games purchased primarily for their stories (unique games). Key: Fully Traditional Story (FTS), Interactive Traditional Story (ITS), Multiple-Ending Story (MES), Branching Path Story (BPS), Open-Ended Story (OES), Fully Player-Driven Story (FPDS).

Respondents’ games purchased primarily for their stories (all nominations).

The five games most frequently listed by respondents were

1. Dragon Age Origins (multiple-ending story)

2. & 3. (a tie) Bioshock (multiple-ending story) and FINAL FANTASY XIII (inter-

active traditional story)

4. & 5. (a tie) Heavy Rain (branching path story) and Mass Effect (multiple-ending story)

Further Analysis

As in the first survey, it’s clear that there are a good number of gamers out there who like the idea of player-driven storytelling, or at least find it rather interesting. However, it’s also clear that when deciding which games to buy, the amount of control and freedom given to the player isn’t a big selling point, as the vast majority of games that are bought for their story use interactive traditional storytelling. In fact, the more player-driven a game’s story is, the fewer people buy the game primarily for its story (which is not to say that a large number of gamers don’t buy those games for other reasons, such as their gameplay). Although several multiple-ending and branching path story games did receive numerous mentions (as evidenced by the top five list), all of those titles were either created by developers with a reputation for telling excellent stories (such as Dragon Age and Mass Effect) or were the subject of numerous ads and positive coverage in the gaming press (such as Bioshock and Heavy Rain), so it seems likely that those factors had far more to do with those games’ popularity.

In the end, stories do sell games. However, although the fact that a particular story is highly player-driven can increase peoples’ interest in a game, it seems to have relatively little effect on sales, with things like the general content and theme of the plot and the reputation of the series and/or developer playing a much larger role.

It’s clear that the majority of gamers prefer games with interactive traditional stories. Multiple-ending and branching path stories were fairly popular as well, though highly player-driven forms of storytelling such as open-ended and fully player-driven stories were not. However, when we looked at the respondents’ actual preferences (as determined by the games they considered to have exceptionally good stories), interactive traditional stories dominated by an enormous margin, with multiple-ending stories trailing nearly 50 percentage points behind and other player-driven storytelling styles ranking even lower. There are a few possible reasons that could partially account for these results, but on the whole they strongly indicate that although gamers do have some interest in player-driven storytelling, they strongly prefer the stories in games using interactive traditional storytelling.

The second survey backed up the results of the first. Story is an important consideration for many people when purchasing games. However, due to the difficulty in gauging the quality of a game’s story before purchase, a lot of gamers focus on games created by well-known developers or those with particularly unique-sounding plots or settings to help them decide. Highly player-driven storytelling does attract the interest of a fairly large number of gamers and rarely drives potential buyers away, but not many consider it to be an extremely important factor when deciding which games to buy. This conclusion is further supported by the respondents’ buying habits, as games using interactive traditional storytelling are purchased primarily for their story far more often than those using any other storytelling style.

In the end, despite what many in the game industry say, what players seem to want and enjoy most in game stories is simply a well-told story, regardless of how much freedom and control they’re given. To that end, interactive traditional storytelling is the most popular style by far, as it gives writers and designers free rein to control and fine-tune the pacing, characters, and plot progression in order to create the best possible experience for the players.

1. Do you agree with the survey results and conclusions discussed in this chapter? Why or why not?

2. Was there anything in the survey results that you found particularly surprising? Why?

3. Did the information presented in this chapter change your opinion about which type of storytelling is best? Why or why not?

4. Look over your answers regarding traditional vs. player-driven storytelling from the previous chapters and discuss how and why your views on the matter have or haven’t changed as you’ve read this book.