CHAPTER

Seven

Fully Traditional and Interactive Traditional Stories

For the next several chapters, we’ll discuss the different types of storytelling shown on the spectrum in detail, along with their uses in games, including the advantages, disadvantages, and specific challenges involved in their creation. In this chapter, we’ll cover fully traditional and interactive traditional stories, as they share a similar structure, with interactive traditional stories building on the foundations set by fully traditional stories.

FIGURE 7.1

Fully traditional storytelling.

Fully traditional stories are the classic form of storytelling, which has been used for centuries. Films, books, plays, and cave paintings are all examples of fully traditional storytelling. The defining characteristic that sets them apart from the other types of storytelling covered in this book is that fully traditional stories are entirely noninteractive. The “player” isn’t a player at all, but rather a viewer who can only watch as scenes unfold. No matter how many times the story is watched or read, it remains unchanged.

Keep in Mind the Nature of Drama

One aspect of storytelling, as mentioned elsewhere, is that dramatic stories (film, plays, and – dare I say – games) all differ fundamentally from fiction in two very important ways. First, in a dramatic story, the story takes place in front of the audience member; the audience member watches the story. This setup has a huge effect, because the audience member’s imagination as to what characters look like, how they gesture, and what the environments in which the story take place look like are all decided by the creative team for the piece. You’ve probably heard people say, after they’ve left the theater having seen a film that was based upon a book, “It looked better in my head.” When the audience experiences this effect, it can jolt them out of the story in an unfortunate way. With an original dramatic work, elements like the way it looks and which actor was cast to play which part either work or don’t on their own merits. Thus, one aspect of traditional interactivity in “words on paper” fiction is taken away in drama. This aspect also has the secondary effect of not allowing the audience to hear characters think, which is often done in fiction. There is no way in drama for the audience to perceive hidden motivation (for example, whether a character is lying) unless they see it through the character’s actions.

The second aspect that makes dramatic stories different is that they are time-bound. The story unfolds at a specific rate (determined by the authors) and the audience must keep up. This aspect is a serious writing challenge that is not present in fiction, because when the author must, for comprehension reasons, make sure that the audience sees and understands something, he or she uses very specific techniques to maximize the chances of understanding. Dramatic writers often talk about something “landing,” which translates to “did the audience get the point?” Also, one of the writing techniques used in drama is keeping one step ahead of the audience, so they don’t figure out the story ahead of the writer. In fiction, readers have total control over the method they use to consume the story. They can go and read the last page if they wish, spoiling the surprise, because there is so much richness in the language of the story that it is often enjoyable to read even if you know the ending. Not so with drama.

This time-bound nature also changes the dynamics of the audience. Dramatic writers must keep the audience engaged; if they grow bored, they do things like change the channel. If readers of a book get bored, they can put the book down and resume later (as long as the book isn’t too boring) or they can skip to the end of the chapter. The dramatic writer is constantly striving to set up the audience with a question, answer the question, set up another, and so on in order to keep tension high and release it all at the end of the story. These are very different writing challenges.

—Chris

Although the viewer of a fully traditional story may have the ability to flip to the back of a book or skip through chapters on a DVD, thereby experiencing the story out of order, this can’t be considered truly interactive. First and foremost, doing so does not actually change the story, but merely the order in which the viewer sees it. Second, as discussed in Chapter 6, when a person turns pages or fast-forwards through movies, that person is not actually interacting with the story’s world or characters but instead with the medium containing the story (the book or DVD). Nothing the viewer does can change the story itself.

Fully traditional storytelling has a rich history and is the style used to tell the world’s most-loved and well-known stories. Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone and the Star Wars movies, for example, are both fully traditional stories, as are ancient tales such as the Iliad, Romeo and Juliet, and the legend of Hercules. Storytellers have spent thousands of years creating and refining the techniques used in fully traditional storytelling, creating a very mature and perfected style that is suitable for telling stories of any length and genre. The strength and beauty of fully traditional stories is that the writer is always in full control of the experience. Because of this, the author can shape the scenes in order to convey exactly the events and emotions he or she wants at exactly the right time. Ensuring proper pacing and keeping characters consistent and believable is far easier in fully traditional storytelling than in any of the other styles we’ll discuss. The only problem is that in their pure form, fully traditional stories can’t be used in video games.

Fully Traditional Stories, Video Games, and Why They Don’t Mix

Video games are, by nature, a medium dedicated to interaction. Whether it’s shooting aliens, pushing crates, talking to townspeople, or rearranging colored gems, all true video games are designed around letting the player interact with their world, characters, and story. The types of interactions allowed and the effect they have on the rest of the game vary significantly, but some level of interactivity is always there.

As such, the concept of fully traditional storytelling and that of video games are innately opposed. There have been some attempts at creating games that use fully traditional stories, but without interaction, is a video game really a video game? In the end, it would probably be more proper to call these “games” movies or digital novels. But that doesn’t mean that they don’t have good stories in and of themselves, with their own unique advantages – they just aren’t true games.

Case Study: Higurashi When They Cry

| Developer: | 07th Expansion |

| Publisher: | 07th Expansion |

| Writer: | Ryukishi07 |

| System: | PC |

| Release Date: | August 10, 2002 (Japan) |

| Genre: | Visual Novel |

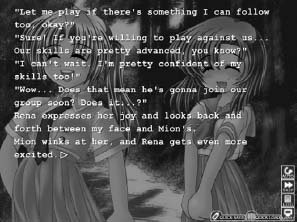

FIGURE 7.2

At first glance, the village of Hinamizawa seems like a peaceful place.

Despite being one of Japan’s most popular visual novel games, Higurashi When They Cry has a very important difference that sets it apart from the rest of the genre. Unlike normal visual novels, which feature complex branching path stories, Higurashi is one of the rare games that uses fully traditional storytelling (for a more detailed look at the visual novel genre and its storytelling methods, see Chapter 9).

As a visual novel, Higurashi’s story is told primarily via pages of text, like a book written in the first person. However, the text is displayed atop background images of the main character’s current location and also features illustrations of the other characters, along with sound effects and a full musical score, making the story far more of an audiovisual experience than an ordinary novel. The player’s only form of interaction is clicking the mouse to advance the text, clearly separating it from other visual novels in which the player takes a much more active role in the story.

Higurashi spans eight separate games (or story arcs), which were released individually over the course of four years. It went on to become a major hit in Japan, spawning novels, comics, an animated TV series, multiple live-action movies, and several ports and spin-off games, along with a wide assortment of merchandise. However, like almost all visual novels, Higurashi wasn’t released outside Japan, though both the anime (cartoon) and manga (comic) were translated and released in the United States. Recently, however, the original Higurashi games were finally made available in English by the European company MangaGamer, allowing the English-speaking world to experience the story the way it was meant to be told.

Set in Japan in the mid 1980s, Higurashi follows teenager Keiichi Maebara, whose family recently left behind the hustle and bustle of Tokyo to move to the quiet mountain village of Hinamizawa. Keiichi quickly finds himself growing fond of his new life and becomes good friends with four of the girls in his school: the highly competitive Mion, the friendly and helpful Rena, the crafty Satoko, and the cute and resourceful Rika. The five of them make up the school’s “unbeatable” club and are constantly challenging each other in all manner of crazy games and activities. Higurashi’s first arc, Onikakushi (which can be translated as Spirited Away by Demons), begins innocently enough, with Keiichi and his friends engaging in a series of enjoyable activities as the village’s annual Watanagashi festival draws near. These early chapters serve as an introduction to Keiichi, the girls, and the village itself, and are a lot of fun to read due to the likable characters and amusing situations they find themselves in. However, Hinamizawa isn’t quite the tranquil place that it seems. Things begin to go wrong when Keiichi learns that for the past four years, on the night of Watanagashi, one person has turned up dead and another has mysteriously disappeared shortly thereafter. Supposedly, all the crimes have been solved and the timing was just a coincidence. However, when visiting photographer Tomitake is discovered the night of the festival with his throat scratched out, the series of murders and rumors about the mysterious curse of Oyashiro are suddenly much harder to ignore. Determined to learn more about Tomitake’s death, Keiichi ends up in over his head when his friends start acting strangely and he finds himself being shadowed by an unknown presence. To make matters worse, he becomes the victim of several near-fatal attacks, all designed to seem like simple accidents but hinting at a much darker intent.

FIGURE 7.3

The village and its inhabitants harbor many dark secrets.

I won’t say what happens next, but Keiichi’s story doesn’t end well and leaves a lot of unanswered questions. In a very interesting twist, rather than continue the story where it left off, the second and third arc cover the exact same period of time – immediately before and after the Watanagashi festival. However, events play out differently each time, leading to new but just as tragic outcomes, with the fourth arc acting as both a prequel and epilogue to the others. Throughout this portion of the story, the player is faced with a myriad of mysteries, few of which are answered, and begins to learn of Hinamizawa’s dark past. Because of this, the first four arcs are known as question arcs and the remaining four (referred to as Higurashi Kai) are answer arcs. The answer arcs continue to retell the story but break away from Keiichi, getting into the heads of the other characters in order to slowly explain the truth behind the murders and strange events of the first four chapters, eventually tying them together into a final epic conclusion to the bloody cycle that shrouds Hinamizawa.

Featuring likable characters that are far more than they first appear, a chilling series of murders, and a complex web of dark secrets and mysteries designed to keep players guessing right up until the end, Higurashi contains one of the most interesting and engaging mystery/suspense stories I’ve ever read, with the art, sound, and music adding quite a lot to the experience. But, despite that, I have a problem calling it a game. With no interaction beyond advancing the text, Higurashi is entirely lacking in both interactive and game-like elements. Even the writer admits it, saying the “game” lies in trying to figure out the answers to the story’s many mysteries before they’re revealed in the later arcs. Although puzzling over the events in each subsequent arc is fun, and something I myself spent many hours doing, the same can be done with any book and in no way allows the player to interact directly with Hinamizawa or its inhabitants. So although Higurashi may be an excellent visual novel, it’s mostly certainly not a visual novel game.

Interactive Traditional Stories

Interactive traditional stories combine the tightly controlled narratives of fully traditional stories with a degree of interactivity. They’re the most common type of video game story, due to a combination of familiarity, structure, and creation process (for more details, see the rest of this chapter and Chapter 13). They’re also extremely popular among players, as shown by the research data in Chapter 14. In an interactive traditional story, the main plot itself can’t be changed, or at the very least can’t be changed in any significant way. As with fully traditional stories, it will be the same no matter how many times the player experiences it. However, outside important story scenes, the player is given a degree of freedom to interact with the world and characters. In some games, the player’s control is minimal and he or she is able to do little besides engage in battles and/or solve some puzzles. In others, however, the player is given a considerable amount of freedom to explore the world, talk to different characters, and engage in a variety of optional quests and activities if he or she so chooses. Although the player’s actions may not have a significant effect on the main plot, they do allow the player to feel somewhat in control and responsible for the characters’ actions and progression.

FIGURE 7.4

Interactive traditional storytelling.

Emotional Architecture

One area of great potential artistic expression is in the area of evoking audience emotion. Regardless of the number of twists and turns a story possesses, the fundamental feature of a player-driven traditional story is what kinds of emotions are available to the writer. For example, in a traditional story, the audience experiences the emotional roller coaster of the story through empathy (“Oh, how sad for her that he left her to run off with the gang; I know someone that happened to, and it really stinks. I feel sad”). But not all emotions translate effectively through empathy. When a character in a drama makes a stupid decision, eliciting guilt from the character, the audience feels bad for him or her, certainly, but guilt is a first-person emotion. However, in interactive stories, emotions such as guilt can be much more powerful because the character is doing the action that the player determined. In the unreleased game Stargate Worlds, we had the players decide to kill an NPC they had interacted with, much akin to the scene in 2001: A Space Odyssey in which the astronaut Dave must deactivate the computer HAL. The players felt the guilt of the decision they made to a degree impossible in standard drama.

—Chris

Case Study: FINAL FANTASY X

| Developer: | Square Co., Ltd. |

| Publisher: | Square Electronics Arts LLC |

| Writers: | Yoshinori Kitase, Daisuke Watanabe |

| System: | Sony PlayStation 2 |

| Release Date: | December 20, 2001 (US) |

| Genre: | RPG |

FIGURE 7.5

FINAL FANTASY X’s hero, Tidus, finds himself pulled into a new and dangerous world. © Square Enix, Co., Ltd. All rights reserved.

Square’s famous FINAL FANTASY series is known for its complex storylines and well-developed characters – and its PlayStation 2 debut was no exception. As was expected of Square, FINAL FANTASY X featured some of the best graphics of its time, a memorable musical score, and many new gameplay innovations (including a more strategic battle system, the ability to switch out party members mid-battle, and the removal of traditional character levels in favor of the new Sphere Grid system). It was also the first FINAL FANTASY game to feature voice acting, with fully spoken dialog for all the major characters. Though die-hard fans of the series’ earlier entries tend to prefer FINAL FANTASY VI or FINAL FANTASY VII, FINAL FANTASY X became the favorite of many of the newer generation of FINAL FANTASY fans and was also the first game in the series to receive a true sequel (FINAL FANTASY X-2).

FINAL FANTASY X starts in the futuristic city of Zanarkand. The main character, Tidus, is the young star player of the Zanarkand Abes blitzball team, but despite his fame, he can’t seem to escape from the shadow of his father, who disappeared years before. However, when a giant monster destroys the city, Tidus awakens to find himself in Spira, a world far different from his own. People in Spira shun technology and instead rely on summoners (humans with the ability to summon and control magical beasts known as aeons) to protect them from attacks by Sin, the same monster that destroyed Tidus’s home. Lost and unsure of how to return to his own world, Tidus falls in with Yuna, the daughter of the former high summoner, and her companions on a journey to gain the aid of the aeons and defeat Sin once more. Unsurprisingly, there’s far more to the role of Sin and the summoners than they realize and the truth about Spira, Zanarkand, the aeons, and even Tidus’s father rocks their beliefs and convictions to the core, causing a drastic shift in the nature and goals of their journey and culminating in one of the series’ most emotional endings to date. In addition, Tidus’s narration throughout much of the game adds an interesting perspective to the events, explaining his thoughts and motivations during each stage of the journey.

FIGURE 7.6

The bond between Tidus and Yuna grows gradually throughout the game. © Square Enix, Co., Ltd. All rights reserved.

Like all the main series FINAL FANTASY games (and most of the spin-offs), FINAL FANTASY X uses interactive traditional storytelling. The main story itself is fixed and the same events always happen in the same order, though the player’s actions can cause some minor modifications to the plot. For example, in one scene, when they break off into pairs, Tidus will be put with the character he’s been the friendliest with. However, these changes amount to, at most, some very slight changes in dialog and have no real bearing on the progression or outcome of the story as a whole. But that doesn’t mean that the player is just an observer. Outside important story scenes, he or she is given a considerable amount of freedom. Naturally, the player is in complete control during battles and is free to fight and develop his party as he pleases, but that’s only the beginning. Despite being one of the more linear FINAL FANTASY games, FINAL FANTASY X still allows the player to travel to and explore a variety of places (some of which make no appearance in the main story). As the player is doing this, he can power up the heroes and learn more about the world, characters, and backstory by talking to NPCs, finding lost video spheres recorded long ago by Tidus’s father, and participating in a large variety of optional quests. Some of these activities have almost no bearing on the main plot and merely give a little more information about Spira and its inhabitants; others provide the answers to some lingering questions that are asked but never answered over the course of the main story.

Despite the player’s lack of control over the story itself, the freedom the player has throughout the rest of the game clearly separates FINAL FANTASY X’s interactive traditional story from the fully traditional stories of books and movies. It also provides a strong illusion of control by giving the player an important role to play and the freedom to perform that role in many different ways. So although the plot itself remains the same, each player’s experiences in the world of Spira are different and unique.

Creating Interactive Traditional Stories

In many ways, interactive traditional stories are the easiest type of video game story to create. As you’ll see in the coming chapters, stories using more highly interactive styles such as branching path storytelling and open-ended storytelling require a considerable amount of extra work and planning to create. With interactive traditional stories, you don’t need to worry about what would happen if the hero decides that he wants to become a villain or take up fishing instead of following the plot as it was originally planned. You don’t need to write out complete scenarios for good, evil, and fisherman versions of the story or struggle to balance character consistency with player choice and freedom. As with a fully traditional story, you control the plot so that you always know how, when, and where all the key scenes are going to play out and can tweak and fine-tune them to produce exactly the type of impact and emotional response you want.

Because the player can’t change the plot, writing an interactive traditional story is in many ways much like writing a novel or a movie script (in terms of formatting, it’s closest to a script, though different developers prefer different layouts and organizational styles). You think of an idea; plan out your basic story, structure, and characters (or in some cases are given all of these by your boss); and then just write the story as you imagine it. Of course, there are some key differences. Unlike with a novel or movie script, you don’t have to write out everything that happens. Though a fantasy novel may describe the hero’s battle with the evil wizard’s army or his journey across the treacherous mountains in detail, in a game the player will be the one actually doing the fighting and climbing, so you merely need to mention that those elements are there and let the designers and then the player handle the rest.

Tone Is Powerful

I have always believed that the most powerful tool a game writer has to tell story is the choice of what the character played by the player does. The more the writer can have influence over the activities the player can partake in, the more the writer can influence the tone, and tone is one aspect of the game many developers do not make as much use of as can a talented writer. One of the game aspects that Bioware does well is awareness of when to be funny, when to be dramatic, and when to mix the two.

—Chris

Of course, if you want to describe what types of creatures are in the army, what they look like, and how they fight, or explain what it is that makes the mountains so dangerous, you can do so in order to give the art and design teams more to work with, though it can vary a lot by where you’re working. Some developers prefer that level of detail and like to try to ensure that everything fits well within the context of the story, but others would rather you leave the character and level creation entirely up to the art and design teams and just adjust the story to fit them.

When writing interactive traditional stories (or any type of story) for games, you also have to remember that you’re not writing for a novel or a movie, but a game. Therefore, you need to ensure that your story provides plenty of places for the player to do his or her thing, whether that thing is fighting, exploring, puzzle solving, or some combination of the three. And that doesn’t just mean leaving space between the story scenes for all those things to happen: you also need to consider how gameplay can be worked into the story scenes themselves. If the story calls for a tense showdown or a daring escape, think about the gameplay and whether it would lend itself to that scene. At times, you may decide that it’s best to leave the scene entirely noninteractive (either for dramatic effect or because it simply wouldn’t work within the confines of the game system), but at others you’ll realize that there’s no good reason not to give the player control. Just keep in mind that the gameplay has to fit. For example, though an interactive battle in a FINAL FANTASY or Metal Gear Solid game should be an actual battle with swords, guns, or fists, an interactive battle in a more puzzle-based game like Sam & Max or Monkey Island should be more of a duel of wits than a button-mashing fight. Even if you’re given free rein over the story, knowing how the game will be played and tailoring your scenarios to fit that specific type of gameplay will make the final product feel far more natural and polished than if your puzzle-solving hero goes around beating down every villain with a kick to the head.

You may also need to think about how the player can interact with the world and characters. Even though the player can’t change the main story, he or she may still be able to talk to NPCs, choose from multiple responses when speaking, and search out books or log entries containing additional information about the world and backstory. Naturally, you need to write all of those extra lines of dialog and information as well. Writing lines for NPCs or in-game books usually isn’t too hard – just start with the subject and work from there. Each book and NPC doesn’t need ten pages of writing or even have to convey anything important or profound. A book or log entry needs to be only long enough to adequately describe its subject; an NPC who makes a brief remark about the weather is just as realistic and believable as one who spews out long rants about the state of the kingdom. Both types of people exist in real life, so there’s no reason why they shouldn’t exist in your game.

Tell Story Every Way You Can

There are no throwaway items created by a writer in the game. Every chance you have to advance the story, you should take. Although it’s true that NPCs the player meets on the street don’t have much screen time, that makes their dialog even more crucial to get right. The cumulative effect of these “barks,” as they are known, can absolutely inform the player as to the world’s fabric in a very powerful way.

Disney’s theme parks are filled with wonderful examples of storytelling that exemplify this ideal. They theme everything, from the costumes of the ride attendants to the coverings on the trash cans to the ride elements themselves. Their design staff preaches about both knowing the story inside and out and telling the story every way you can. Their success and the depth of storytelling at which they routinely succeed speaks for itself. It would behoove game storytellers to resist the urge to pander to the lowest possible inside jokes, and when they need to be funny, to find a way to be funny in a way that is organic to their game world.

—Chris

We’ll talk a lot more about writing branching dialog in later chapters, but it’s a bit easier in interactive traditional stories because the different branches always eventually end up in the same place without changing the story. So instead of thinking about how different dialog choices could change the story, think about how they can be used to provide additional information or show different ways the character could react to a certain request or situation. For example, when the hero is talking to a character about a dragon that needs to be killed, you could give the player the option to ask for more information about the dragon, ask about the damage it caused to the village, or just get right down to business and head out. None of these dialog choices will change what happens next, as the dragon still needs to be dealt with, but they give players the option of learning more if they want to and increase the interactivity and the illusion of control (an important concept that we’ll discuss more in Chapter 13). If you prefer your branching dialog to be based around reactions rather than information, the hero could have the option to immediately agree to fight the dragon, to ask what’s in it for him, or to try and weasel out of it. Once again, the story remains the same, with only a few lines of dialog changing, but the extra options increase the interaction and illusion of control.

Player’s Characters Speaking Dialog

There are widely varying opinions about putting words in a player–character’s mouth. Some players have said they don’t ever want the game speaking for them, so the game should always speak generically for the player, as in “You ask the barkeeper about the best place to change money.” Other people believe, as I do, that you must embrace your role as author and pick a tone for the player–character’s voice, as many Bioware games do. “Hey, dude, where can I get some cash?” feels much different and delivers a totally different tone to the main character than “Um, sir, can you help me find the bank?” As the writer, you should make a choice. The power is always in a stronger choice rather than a weaker one.

—Chris

One very important thing to remember when creating branching dialog for an interactive traditional story is that even though the eventual outcome remains the same regardless of what is said, the choice the player makes should still change the conversation, with the other character reacting in an appropriate manner. When game writers add extra dialog choices merely for the sake of having something for the player to choose from or click on, without bothering to change the rest of the conversation to match, you end up with one of two highly undesirable scenarios. The first is when, after the player chooses his or her response, the other character continues talking without acknowledging the player’s choice in any way. No matter which option the player chooses, the conversation remains exactly the same. While players might not notice this their first time through if the conversation is written well enough, those that do will probably be annoyed by it. A much worse version of this is when the player is given the choice between two or more lines of dialog that say pretty much the same thing. I won’t name names, but I’ve played at least several games in which I was given the choice between saying “yes” and “yeah” (or two other more or less identical words). A choice like that is completely pointless and leaves the player wondering why he or she was even given a choice in the first place – there’s nothing to choose between.

The second bad scenario takes place when the player is given the choice between two or more opposing options. Let’s say that the player can accept or refuse a certain job. The problem is that the story requires the player to take (or maybe not take) that job, so only one option is actually valid. Choosing the wrong option will result in the NPC saying something like “Are you sure?” and giving the player the same choice over and over again until the right one is chosen. This type of conversation actually could be handled well if choosing the wrong option caused the NPC to reason with the hero and convince him to do the right thing, but just looping the choice endlessly until the player gets the hint and picks the right option is pointless and annoying. Although branching dialog options don’t need to change the main story, they do at least need to have some purpose to them – otherwise, you’re just making pointless busywork for the players.

Case Study: Metal Gear Solid 4: Guns of the Patriots

| Developer: | Konami |

| Publisher: | Konami |

| Writers: | Hideo Kojima, Shuyo Murata |

| System: | Sony PlayStation 3 |

| Release Date: | June 12, 2008 (US) |

| Genre: | Stealth Action |

FIGURE 7.7

Solid Snake has aged significantly since his last outing.

Metal Gear Solid 4 didn’t become the final game in the Metal Gear series as was originally intended (though all later releases have so far taken place earlier in the series’ fictional timeline), but its release brought to a close the story that had stretched through the rest of the series (aside from Metal Gear Solid Ghost Babel and Metal Gear Ac!d, spin-off titles with their own continuities) from Naked Snake’s defeat of The Boss in MGS3, through his own defeat in MG and MG2, and onward through Solid Snake and Raiden’s adventures in MGS and MGS2. When it was released, MGS4 impressed gamers not only with its highly detailed graphics and revamped control system, but also with the way it expertly tied up the myriads of mysteries and loose ends from past games in a way that both made sense and provided a satisfying and emotional conclusion to the story – something that many fans, myself included, had thought to be nearly impossible.

With the exception of the first MGS, which had a multiple-ending story, the series has always used interactive traditional storytelling to great effect. Though the series is occasionally derided for its long cut-scenes, it is frequently praised for its cinematic action scenes, long conversations between characters, and top-quality voice acting, which all serve an important purpose: causing the players to truly care about the characters, their goals, and their motivations. The graphics quality in MGS4 further upped the ante, showing the characters’ body language and subtle facial shifts far better than ever before, making for one of the most emotional stories in gaming and a frequently cited example of a game that can make people cry.

Set a few years after the events of MGS2, Snake is now an old man, due to a flaw in his genetics that has caused his body to suddenly and rapidly age. As Snake has changed, so has the world. Seemingly channeling the spirit of Snake’s brother Liquid, Revolver Ocelot has created a series of private military corporations – armies for hire that are willing to serve whoever will pay. The use of emotion-suppressing nano machines has made these soldiers fearless and loyal: the perfect warriors. War has become a business, and business is good. Though still on the search for Ocelot and the shadowy group known as The Patriots, with Raiden missing and Snake’s body rapidly deteriorating, he and Otacon have reached a dead end. However, when Ocelot resurfaces, Snake returns to the battlefield one last time to put an end to things once and for all. Snake’s final mission features many interesting characters, both old and new, and reveals the shocking truth behind mysteries including Big Boss’s defection, Ocelot’s goals, and the identity of The Patriots.

FIGURE 7.8

Metal Gear Solid 4 has a very diverse cast of characters, new and old.

Like previous MG games, MGS4 plays to the strengths of interactive traditional storytelling. Although the story scenes are scripted, unchangeable, and, with a couple of exceptions, noninteractive, this allows them to be done in a highly cinematic style that highlights the intense and breathtaking events. The story also features many shocking and emotional moments of the sort that are extremely hard to create when using more interactive and player-driven storytelling styles. (We’ll discuss the reasons for that throughout the upcoming chapters.)

However, despite the unchanging and linear nature of the story, players have a significant amount of control and freedom available to them during the rest of the game, even more so than in the rest of the series. The story guides Snake through a series of war-torn battlefields but provides him with an endless variety of ways to pass through them. Stealth has always been Snake’s specialty; he can choose to use his natural abilities and new camouflage technology to try to slip by unseen. But he can also take a more aggressive role, silently dispatching guards with a wide variety of weapons or distracting them through other means. Unlike the areas in previous MG games, which generally had only one path, the environments in MGS4 are large and varied, providing many possible routes, each with its own advantages and disadvantages. Several areas also feature pitched battles between Liquid’s soldiers and local freedom fighters. Although sneaking past them is always an option, players can also choose to aid the locals in their fight, allowing them to push forward, open new paths, and clear areas of enemy combatants. Or, if the player chooses, he or she can act as a lone wolf, dispatching soldiers on both sides of the conflict and taking their equipment to aid him in future battles.

This high degree of freedom in the gameplay makes each player’s experience unique and allows for considerable experimentation and replay value while still providing the kind of deep, twisting, and tightly controlled narrative that fans of the series love. There are many games on the market that provide good examples of how to tell an interactive traditional story, but from its haunting opening to its tearful conclusion, MGS4 is certainly one of the finest.

The Strengths of Interactive Traditional Stories

The strengths of interactive traditional stories lie in the fact that it’s the writer who controls the flow, progression, and outcome of the main plot. Just as the writers of fully traditional stories have done for centuries, writers of interactive traditional stories can arrange and fine-tune every scene to ensure that it conveys the correct information and emotions in the best possible way. And, unlike in the more player-driven forms of storytelling, you don’t need to worry about the player screwing up the story, missing some important piece of information, or losing track of the main plot. When well written, an interactive traditional story can carefully control the players’ emotions, beliefs, and expectations and guide them toward a planned goal, whether that goal is a surprising twist or a satisfying conclusion. This no doubt contributes to their high popularity (see Chapter 14).

From a more practical standpoint, keeping the characters and story consistent and believable is far easier to do than in other more player-driven storytelling styles because there’s no danger of the player mixing things up. You also don’t need to think of suitable places for the story to branch, write multiple variations of the story scenes and conversations, or try to figure out how to make the plot interesting and engaging no matter which way it branches (issues that we’ll discuss in depth in the upcoming chapters), all of which can take a considerable amount of time and money to plan and implement.

In the end, when done correctly, interactive traditional stories provide players with a well-structured, tightly woven experience that – like a good book or film – showcases the writer’s imagination and creativity to the fullest. At the same time, they can provide players with a strong illusion of control, allowing players to feel that they have an important role to play in the story, even though they can’t change the main plot itself.

Case Study: FINAL FANTASY VII

| Developer: | Square Co., Ltd. |

| Publisher: | Sony Computer Entertainment, Inc. |

| Writers: | Tetsuya Nomura, Hironobu Sakaguchi |

| System: | Sony PlayStation |

| Release Date: | September 7, 1997 (US), June 2, 2009 (PlayStation Network rerelease) |

| Genre: | RPG |

FIGURE 7.9

Cloud and Sephiroth are still famous figures among gamers. © Square Enix, Co., Ltd. All rights reserved.

As I mentioned in Chapter 2, FINAL FANTASY VII is a very important title in the history of games and game storytelling. Not only did it elevate console RPGs from a niche market in the United States to one of the most popular genres in existence, but it also showed both gamers and game developers outside Japan that a good story could both define a game and attract a significant audience. The explosion of RPGs and story-focused games of all types that followed brought stories – which were before often considered to be one of the less important elements of games – to the forefront in the eyes of many developers and gamers.

But what made FINAL FANTASY VII so popular that the industry as a whole had to stand up and take notice? Was it the state-of-the-art graphics and amazing FMVs, or perhaps Square’s massive multimillion-dollar marketing campaign? Clearly not. Those factors no doubt helped to get it in the public eye and convinced gamers unfamiliar with the FINAL FANTASY series to give it a try, contributing to the strong sales during its first weeks; however, those elements can’t account for the way it continued to dominate sales charts for months after its initial release, its enduring popularity, or the sheer amount of praise lavished upon it by the gaming press both back then and now. Its excellent musical score and solid gameplay were also only small parts of the puzzle. FINAL FANTASY VII’s greatest strengths, and the reasons for its immense popularity (which has led to multiple sequels and prequels, along with an endless stream of fan requests for a full remake), are its characters and story.

FINAL FANTASY VII starts in Midgar, a massive city run by the Shinra Corporation. From its beginnings as a simple power company, Shinra grew rapidly, taking over other industries and eventually the government itself. Though most people seem content with Shinra rule, rumors abound of a darker side to the company involving highly questionable experiments and power plants that suck the very life force from the planet. Cloud, a mercenary and former member of Shinra’s elite Soldier division, has been hired by the guerilla group Avalanche to help destroy Shinra’s mako energy plants and bring down the company. Despite his childhood friend Tifa being a member of Avalanche, Cloud is only in it for the money and has no interest in the group’s ideals. But a series of events – including a chance encounter with the flower girl Aerith (spelled Aeris in the original release), the destruction of a large section of Midgar, and the sudden reappearance of the legendary soldier Sephiroth (who destroyed Cloud and Tifa’s home town five years before) – give him a new purpose. The story is rife with surprising twists and revelations, including the extent of Shinra’s twisted experiments, Sephiroth’s plans, and the truth about Cloud’s memories and the events of five years ago.

FIGURE 7.10

Aerith’s death shocked and saddened millions of players. © Square Enix, Co., Ltd. All rights reserved.

I discussed a few of these elements in earlier chapters, such as the unique way FINAL FANTASY VII uses the old amnesia cliché to set up a series of fascinating twists late in the game, but there’s more to the story than just the big reveals. What’s most important is the characters. Each of Cloud’s companions, from the sweet flower girl Aerith to the wolf-like creature known as Red XIII, has his or her own detailed backstory, well-developed personality, and reason for joining Cloud on his quest. The stories of their lives are interwoven throughout the main narrative, and their conversations – both serious and casual – clearly reflect their different beliefs and personalities. The steady and well-directed flow of events helps keep players engaged and wrapped up in the story, with every town and dungeon bringing about new information and developments. Even enemies such as the group of Turk agents who pursue Cloud’s party feature well-defined personalities and relationships.

Sephiroth is exceptionally well done and has become both one of the most loved and hated villains in gaming history. Instantly recognizable, with his black cape, flowing silver hair, and impossibly long sword, the former Shinra Soldier First Class was once hailed as a hero but turned against not only Shinra but the world itself when he discovered the truth about his origins. This important event, shown as a playable flashback through Cloud’s eyes, does an excellent job of demonstrating Sephiroth’s power and his rapid descent into madness. At first he seems redeemable and even a possible ally against Shinra, but his focus on world destruction and his hand in Aerith’s death (an event frequently called one of the most emotional moments in gaming) earned him the eternal hatred of not only the game’s heroes but many of its players as well.

Like the rest of the series, FINAL FANTASY VII shows what is truly great about interactive traditional stories. Excellent pacing, a diverse cast of fully developed characters, emotional high-impact scenes, and a deep twisting plot revealed gradually over the course of a grand adventure – all elements that become increasingly difficult to create in the more highly interactive styles of storytelling – take center stage to create a game whose impact on its players and the industry as a whole can’t be overestimated.

The Weaknesses of Interactive Traditional Stories

Some consider the lack of interactivity and player choice in interactive traditional stories to be a significant weakness, but that’s a highly debatable point – and one that we’ll discuss more in Chapters 12 through 14. The interactivity issue aside, it can actually be argued that the biggest weaknesses of interactive traditional storytelling aren’t so much problems with the style itself, but with individual writers.

As I’ve said throughout this chapter, more than any other style, interactive traditional storytelling gives writers a chance to truly shine, putting them in control of every aspect of the main plot and giving them free rein to develop and present it the way they see fit (bosses and deadlines aside). The problem is that if the player doesn’t like the way the story turns out, there’s really nothing he or she can do about it. Of course, even the best and most well-loved stories have their critics. Like I said before, you can’t please everyone. But, if a story angers, annoys, or disappoints a large number of players, it’s reasonable to assume that there’s something wrong with the story itself. There are a million different things that can go wrong with a story. We’ve already discussed issues like poor pacing and overreliance on clichés, melodrama, and overly generic or unbelievable characters, all of which are common missteps found not only in games but stories of all types. The other most “popular” place for a story to derail is the ending. As previously mentioned, endings can be tricky to write, and it’s important to be sure that they provide a sense of accomplishment and closure. Although a poor ending can ruin a story in any medium, avoiding this problem is especially important in video games because the player feels partially responsible for the story’s outcome (even if the player couldn’t change the plot itself). You want players to finish a game feeling like what they did meant something, not like they just dedicated thirty hours of their lives to something only to fail. This is a very important part of writing for games, which we’ll talk more about in later chapters.

Case Study: Arc the Lad II

| Developer: | Sony |

| Publisher: | Working Designs |

| Writer: | Kou Satou |

| System: | Sony PlayStation |

| Release Date: | April 18, 2002 (US), November 23, 2010 (Playstation Network rerelease) |

| Genre: | Strategy RPG |

Though originally released in Japan in 1996, it wasn’t until 2002 that Arc the Lad II was brought to the United States as part of Working Designs’ Arc the Lad Collection. Picking up shortly after the ending of Arc the Lad, Arc II greatly expands on the first game’s world, story, and gameplay and completes the storyline that it began. It’s even one of the rare sequels that allows players to directly import their party from the first game, retaining all of their characters’ levels and items.

The first part of the story focuses on Elc, a bounty hunter and warrior for hire. He and his friend and fellow hunter, Shu, end up on the wrong side of a dangerous group of people when trying to protect Lieza, a girl with the ability to talk to monsters, and end up on the run. As it turns out, Elc, Lieza, Shu, and the friends and companions they meet along the way all have reasons to fight against the evil empire of Romalia. This common ground leads them to eventually meet and join up with Arc and his allies from the first game as they set out to stop Romalia’s ambitions and prevent its leader from releasing an ancient evil being known as The Dark One, which was sealed away long ago.

The vastly improved gameplay, long quest, and numerous optional missions available at the various hunter offices scattered throughout the world are all significant improvements over the first Arc. The story received a similar improvement. Arc II features a large cast of characters, all of whom have their own detailed backstory and optional quests, and the main plot itself is very long and detailed, featuring far fewer clichéd moments than in the first game. Arc and Elc’s journey is a massive tale that has them traveling all over the world, freeing people from Romalia’s rule, seeking out allies, and tracking down and defeating Romalia’s top generals. There are many shockingly dark twists along the way, making for a very serious and mature story that would easily take several pages to adequately summarize.

The place where Arc II unfortunately stumbles is its ending. As I said before, Arc and Elc’s goal is both to stop Romalia from taking over the world and prevent the release of The Dark One. As it turns out, however, Romalia’s leader is surprisingly intelligent. Unlike most villains, who are certain that they can control whatever unstoppable evil force was sealed away long ago by people much more powerful than they are, he fully realizes that releasing The Dark One would be a very bad idea and is instead content to carefully siphon its power to strengthen his own forces. Unfortunately, when Arc’s party breaks into his throne room (having penetrated his final stronghold and defeated his last and strongest followers), he understandably panics and decides that releasing The Dark One is his only hope. Upon release, The Dark One immediately kills Kukuru (Arc’s girlfriend), and its very presence triggers a devastating series of natural disasters that go on to destroy a significant portion of the world, killing most of the people the player spent hours and hours helping and befriending throughout the course of the game. If that wasn’t bad enough, upon defeating The Dark One, Arc and his friends discover that it can’t be fully destroyed and will recover soon unless Arc sacrifices his own life to seal it away. A pretty tragic ending, right? Well, actually it’s not quite over yet. Once the seal is restored, Romalia’s fortress naturally starts to collapse, prompting the usual clichéd escape scene. But said escape doesn’t go so well. Though the surviving heroes do manage to get out alive, one is seriously injured in the process, suffering permanent brain damage. In the end, though the heroes technically won, it certainly doesn’t feel anything like a victory.

Now I’m not saying that games need to have happy endings. Several games we’ve already discussed (CRISIS CORE – FINAL FANTASY VII, Metal Gear Solid 3 & 4, and FINAL FANTASY X) feature endings that certainly can’t be summed up by saying “and they all lived happily ever after.” However, their endings all leave the player with a sense of accomplishment and the knowledge that although some terrible sacrifices were made, the heroes completed what they set out to do and made the world a better place because of it. Arc II’s ending, however, tends to leave players feeling like almost everything they did was a waste. Yes, they helped and freed a lot of people, but in the end most of those people were killed, rendering all the players’ hard work pointless. Even worse, the destruction of the world and the deaths of Arc and Kukuru are entirely the heroes’ (and by extension, the player’s) fault. If they hadn’t stormed in to stop Romalia’s leader from releasing The Dark One, he never would have done so in the first place. Although life under a tyrannical ruler certainly isn’t great, most people would probably agree that it would be preferable to destroying over half of the world. In the end, it’s quite clear that things probably would have turned out much better if Arc and the others did things a bit differently or even decided to go home and forget about Romalia entirely. And the last thing you want players to feel after more than 50 hours of gameplay is that things would have been better off had they done nothing at all.

Arc II’s ending could have worked as the bad ending in a multiple-ending story or even made for a workable (though rather depressing) ending to an interactive traditional story if the result felt inevitable, rather than being the heroes’ and player’s fault. And therein lies interactive traditional storytelling’s biggest weakness. Without any branches or choices to be made, a single poorly written section can significantly detract from or even entirely ruin an otherwise good story.

Fully traditional stories are the oldest form of storytelling and have been used for centuries in fables, folklore, books, and movies. They give the writer complete and total control over the experience, allowing him or her to set the scenes perfectly to try and ensure that the correct information, impact, and emotions are conveyed. However, as fully traditional stories are unchangeable, they can’t really be interactive and are therefore unsuitable for video games.

Interactive traditional stories are the most common type of story used in video games and seek to blend the best elements of fully traditional stories (such as the carefully controlled and fine-tuned pacing, scenes, and characters) with a measure of interactivity and player control. Though the main plot itself is unchangeable, players are given freedom to explore, interact with the world and its characters, and generally take their own approach to the rest of the game, giving them a strong illusion of control. Compared to other more player-driven forms of storytelling, interactive traditional stories are easier to create and give the writer more control over the finished product, giving them the best possible chance to create the type of story they want, whether it’s an emotionally charged drama, an over-the-top comedy, or anything in between. This makes them very popular with both game developers and players. However, as the main plot is entirely under the writer’s control, any mistakes or poor choices on the writer’s part can seriously damage the story, disappointing and/or angering players.

1. Do you consider “games” using fully traditional stories, such as Higurashi, to be true games? Why or why not?

2. List ten games you’ve played that use interactive traditional stories (if you haven’t played that many, just list the ones you have).

3. Pick three of the games from your list. In what ways did they allow you to interact with their world and characters?

4. When you were playing those three games, were there any times that you really wanted to take control and change the story? Explain why and how you wanted to do so.

5. Do you think the changes you proposed in your last answer would have made the rest of the stories significantly better or worse? Why or why not? Do you think most other players would agree with you?