CHAPTER

Nine

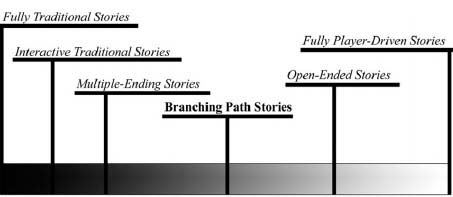

Branching Path Stories

FIGURE 9.1

Branching path storytelling.

While multiple-ending stories only allow the player to choose the game’s ending, branching path stories insert multiple decision points throughout the story, allowing the player to make a series of choices as he or she progresses through the game. Though some of these decisions have little to no lasting effects on the main plot, others can change it significantly, causing it to branch off in another direction entirely (hence the name). Branching path stories have multiple endings, but unlike in multiple-ending stories, the player doesn’t follow the same path to reach all of those endings. Because of this, they allow for far greater player freedom and control, granting the player significant power at multiple points throughout the story rather than just at the very end.

What truly makes branching path stories unique is that unlike open-ended stories and fully player-driven stories (covered in Chapters 10 and 11), they’re built around a very rigid structure of decision points and branching paths leading off those points. Though the player makes a choice at each branching point, the writer retains strict control over the points themselves and everything that takes place in between them. Though it can be difficult to write, a well-done branching path story can provide the perfect bridge between the more structured, writer-focused storytelling styles and the more open, player-driven ones, telling a carefully controlled story while still providing the player with a number of important decisions. This combination of well-structured story and player choice has helped branching path stories gain popularity (see Chapter 14), and they’ve recently been used in some very high-profile games.

Multiple Branches Multiply the Cost

Though it is absolutely true that branching path stories can be glorious (and I have designed two of them), there is one big issue when building them: cost. Game publishers being a prudent lot, they really want to pay only for content that will be seen by the game player. And because multiple-path stories aren’t just words on the page when created but voice-over dialog as well as locations, characters, and so on, there is a real chance with these games that content will be created that the player may never see – even with repeated playthroughs.

When you’re a writer, pressure gets brought to bear on your team to design for these multiple paths, but also to reuse material created for one story purpose when sending a player on another side path, which can negate the exciting nature of these alternate paths. Most successful versions of games like this are written stories with limited graphics and other audio visual elements, as these elements can quickly become very expensive to create.

Aidyn Chronicles: First Mage used a typical method to mitigate this issue. We had one main storyline without much branching. The story nodes were location-based, meaning that the story advanced when the player traveled to certain cities. There was technically nothing stopping the player from skipping ahead (we blocked paths with boulders in only a couple crucial locations when the story would truly unravel if the player got too far ahead), but players had to complete certain tasks in a certain order to move the story forward, and the NPCs that would facilitate that advancement were only in particular cities.

We branched the story via the make-up of the hero’s party. Along the way, the player could add/subtract traveling companions from his or her party, not only to increase a certain set of skills so as to meet the opposition more effectively, but also to alter the way in which the story unfolded. These party members would carry with them story elements, and these story elements would play out only if those members were actually in the party at the time.

As an example, one party member was the hero’s girlfriend. Well, she would turn out to be the hero’s girlfriend at the end of the story if she were in the party at that time and hadn’t died along the way, but during the game the romance would be blooming. That relationship would grow in one way if the hero’s party didn’t have a competitor for her affections, and a completely different way if the hero had added a second female as a party member. After that NPC was added to the mix, she and the original girlfriend would fight over the hero as the game progressed, and eventually the hero would be put in a position in which he would have to choose which girl to go with.

This is an example of how, on the A-story level of the main plot, the story didn’t branch, but branched on the B-story level, yielding a different emotional tone to the game depending on the composition of the party.

—Chris

Case Study: Choose Your Own Adventure Books

| Writers: | The series featured 32 different authors; the two most prolific are R.A. Montgomery and Ed Packard, with 60 books each. |

| Publisher: | Bantam Books (original publisher) and Chooseco (current publisher) |

| Release Dates: | 1979–1998 (original series) and 2005–present (Chooseco reprints) |

Though not the first books to make use of branching path stories, the well-known Choose Your Own Adventure series is responsible for popularizing the concept. Generally well received, Choose Your Own Adventure books were an extremely popular children’s series in the 1980s and early 1990s, spanning over 300 volumes and selling more than 250 million copies, while also inspiring a wave of copycat titles. Though the popularity of branching path books eventually waned, leading to the series’ cancellation in 1998, Chooseco began republishing them in 2005 with moderate success.

The series followed a very predictable structure. You (the reader) were on a great adventure. You might be a famous explorer, cunning general, master detective, or one of a variety of other professions, or you might just be an ordinary person who was in the wrong place at the wrong time. Regardless, something big is going on and you’re right in the middle of it. As the story unfolds, you frequently find yourself facing various important decisions. There are two or three possible choices per decision, each one prompting you to turn to a different page to see the outcome. Quite often, your choice would lead to a grisly death, forcing you to flip back to the last decision point and try again, but at times your choices would lead you down different paths and, eventually, to one of the book’s handful of good endings.

Though famous for their interactivity and novelty appeal, the stories in Choose Your Own Adventure books are extremely shallow, which is likely one reason for the demise of both the series and the style in general. Though it could be argued that many children’s stories are shallow when compared to those geared toward older audiences, the Choose Your Own Adventure books simply didn’t have the length required to tell a strong story. Each book averaged around 120 pages, with anywhere between 20 and 40 of those pages occupied by the various available endings. That left very few pages for any sort of serious plot or character development, especially as those remaining pages were divided between several story paths. In addition, the story paths and endings often contradicted each other, preventing any larger narrative development from taking place when they’re combined. Journey Under the Sea, for example, is 117 pages long with 42 endings and revolves around a deep sea search for the lost city of Atlantis. Although the vast majority of the endings involve the hero dying or giving up the search, he can also discover that Atlantis is an ancient undersea civilization ruled by an evil king, an ancient undersea civilization split into two warring factions, a secret government research facility, an alien base, or a passage to the center of the earth. Some of the later titles reduced the number of endings and decision points, focusing more strongly on the story and consistency, but even the best Choose Your Own Adventure stories never approached the level of plot and character development found in ordinary children and young-adult books.

Despite their flaws, the Choose Your Own Adventure books are still fun to read and provide the perfect example of how branching path stories work. Games, however, have several key advantages, including much greater length and the lack of physical pages to flip (which make it easy to lose your place or cheat and jump to a section you haven’t reached yet), which has allowed them to expand on and show the true potential of branching path storytelling. However, as Chris pointed out, the cost of creating a branching path story in games can be a significant drawback.

Creating Branching Path Stories

Branching path stories take a lot more work and planning to create than do similar interactive traditional or multiple-ending stories. You start off the same way, by creating a basic concept and outline for your story. After that, however, you need to look carefully at your story’s structure and decide where the decision points are going to be, what purpose each branch is going to serve, and how the various branches combine and separate over the course of the story. Other important issues include ensuring that the branches aren’t too similar to each other and that the story remains interesting and engaging regardless of which way it branches. Length can also become a major issue, as a 200-page interactive traditional story could easily take 300 or 400 pages or maybe more to tell as a branching path story. And when it comes to games, the writing is only the beginning, as each branch will have its own art, programming, and sound needs as well. We’ll discuss all of these issues and how to approach them over the course of this chapter, but first it’s important to understand a bit more about how branching path stories are structured.

Each time the player makes a decision in a branching path story, the plot branches off in one of two or more different directions. However, not all branches are created equal. Branches can be divided into three distinct groups – minor, moderate, and major – each of which serves a different purpose in the structure.

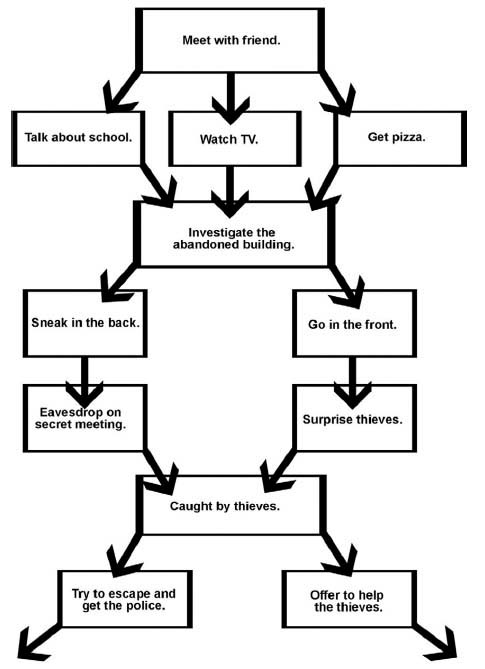

FIGURE 9.2

An example of a branching path story structure.

Understanding the differences and uses of each of these three branch types is critical when creating branching path stories. Figure 9.2 shows the structure of the opening section of a fictional branching path story. It contains all three types of branches and will be used to explain the primary differences between them.

Minor Branches

Minor branches rejoin the main branch very shortly after branching off. As such, they have little to no significant effect on the story and serve only to offer several different versions of a single scene. In our sample story, the first branch is a minor one. After the hero meets a friend, the player can choose to have the two of them talk about school, watch TV, or get pizza. Unsurprisingly, this isn’t a very important choice, and all three lead to minor branches that converge when the hero decides to investigate an abandoned building. However, even though none of these branches have a lasting effect on the main plot, their scenes can be used to convey backstory, character development, or hints about future plot developments.

Moderate Branches

Moderate branches are the next step up. Like minor branches, they eventually rejoin the main branch, preventing them from having a significant impact on the main plot. However, they take far longer to rejoin the main plot than minor branches do, allowing them to present very different scenarios that lead to the same eventual destination. In our example, while investigating the building, the hero can choose to sneak in the back, which leads to his finding and eavesdropping on a meeting between thieves, or he can go in the front, in which case he runs into the thieves almost immediately. Either scenario eventually ends with our hero getting captured by the thieves, but it takes time for the paths to rejoin. As with minor branches, each moderate branch can contain interesting information not present in the other branches, just as choosing to sneak in the back is the only way for the hero to listen in on the thieves’ meeting and learn of their plans.

Major Branches

Minor and moderate branches serve to modify their main branch; major branches break away entirely. Instead of rejoining the main branch later on, they form new main branches, each with its own set of minor branches, moderate branches, and endings. In our sample story, a major branch comes at the very end. After being captured by the thieves, the hero can try to escape so he can call the police or he can offer to join the thieves instead. It shouldn’t be too surprising that this choice has major ramifications on the plot, causing what was a single main branch to split into two. In one, the hero goes on to fight crime; in the other, he seeks to become a master criminal himself. Though some of the same characters and situations may occur along both branches, the two remain separate for the rest of the game, creating two very different storylines.

Because major branches are the only ones that significantly alter the story, you can’t have a true branching path story without at least one major branching point. Both minor and moderate branches, however, can be used in interactive traditional stories and multiple-ending stories, as they provide only minor modifications to the overall story. In fact, if you look back at the games we discussed in the previous several chapters, you’ll see that many of them use minor branches, letting the player steer conversations or small events in different directions, and a few (such as Mass Effect) contain moderate branches that allow players to tackle certain quests or goals in two or more different ways.

One thing to keep in mind is that although most branching points are presented to the player as a clear choice between two or more options, that doesn’t mean that the results need to be obvious as well. In FRONT MISSION 3 (which we’ll discuss in a moment), the first branch involves choosing whether the main character helps his friend with a delivery. On the surface, this seems like a very minor decision, but it’s actually a major branching point, dividing the story into two very different main branches depending on which option is chosen.

As in multiple-ending stories, choices don’t always need to be the result of a conscious action on the part of the player, either. In Fate/Stay Night (a visual novel game discussed in greater detail later in this chapter), there are several branching points at which the choice is made automatically based on how friendly certain characters are with the hero, which is determined by the choices the player made at various minor and moderate branching points earlier in the game.

Finally, though each branching point in the sample image uses only a single type of branch, there’s no reason a single branching point can’t have one option that leads to a minor branch, one to a moderate, and one to a major, or any combination of the three. Mixing things up will make your structure more interesting and a whole lot less predictable.

Case Study: FRONT MISSION 3

| Developer: | Square Co., Ltd. |

| Publisher: | Square Electronic Arts LLC |

| Writers: | Kazuhiro Matsuda, Norihiko Yanesaka |

| System: | Sony PlayStation |

| Release Date: | March 22, 2000 (US), December 21, 2010 (Playstation Network rerelease) |

| Genre: | Strategy RPG |

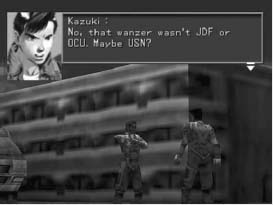

FIGURE 9.3

FRONT MISSION 3’s story is rife with warring factions and political intrigue. © Square Enix, Co., Ltd. All rights reserved.

FRONT MISSION is one of Square Enix’s lesser-known franchises, particularly outside Japan, as only four out of ten games have been released overseas. Originating on the SNES and continuing on to current generation consoles, FRONT MISSION is set on Earth in the near future. Many of the world’s countries have combined into a set of super nations that include the USN (North and South America), OCU (Japan, Australia, and much of Southeast Asia), and EC (Europe). Despite this new unity, wars and civil strife are common. The new weapon of choice is the Wanzer, a giant humanoid robot that comes in many different forms and can be heavily customized to suit the pilot’s preferences. The gameplay places a heavy focus on battle strategy and Wanzer customization, with some games like FRONT MISSION 3 encouraging players to disable and capture enemy Wanzers rather than destroying them outright. The series has been frequently praised for its depth, though the complexity has also been known to intimidate new players.

FRONT MISSION 3’s heroes are Kazuki and Ryogo, a pair of young Wanzer test pilots in Japan. When Kazuki’s stepsister is caught up in an attempted coup by the Japan Defense Force, who have stolen a newly developed super weapon named MIDAS, the friends set out to rescue her. They eventually end up traveling through much of Asia and Eastern Europe, working as mercenaries for hire while gaining allies and trying to track down and stop MIDAS. Though much of FRONT MISSION 3’s story is told via cut-scenes and character conversations, it does contain a rather novel way of fleshing out its characters and setting. Between battles, players have access to an in-game version of the Internet. Each party member has his or her own email address and receives letters throughout the game. Players can carry on the correspondences by choosing from various predefined replies, steering the conversations in the direction they choose. In addition, players can access a variety of “websites” that contain information related to the various locations, people, and corporations in the game. There’s a massive amount of information available, greatly expanding on the setting and backstory, though many of the sites can be accessed only after Kazuki has learned of their existence from conversations, emails, or other sites. Some even require a good bit of searching and a little “hacking” in order to uncover. This makes for a fun optional way to delve further into the game’s story and also rewards thorough players with some special Wanzer parts and other bonuses.

FRONT MISSION 3 uses a branching path story. The first branch occurs near the beginning of the game when Ryogo asks Kazuki to assist him on a delivery. At first glance, this seems like a very unimportant choice. However, it actually constitutes the game’s only major branching point. If Kazuki stays behind, he’ll receive Alisa’s desperate email message the moment it arrives and rush to her aid in time to save her from her kidnappers, only to be framed for the destruction of a research base, forcing them to flee and seek a way to clear their names. But if he goes on the delivery, he won’t see the email until he gets back and arrives too late to save Alisa, instead teaming up with a USN officer named Emma to chase after the people that took Alisa and MIDAS. Although both stories primarily revolve around Kazuki and Ryogo’s search for MIDAS and have them traveling to many of the same locations, the details vary considerably. With the exception of Kazuki and Ryogo, each branch has its own set of playable characters. Furthermore, depending on which branch was taken, the pair will find themselves on different sides of various regional conflicts. In Alisa’s branch, for example, Kazuki and his comrades join the DHZ (formerly China) in an effort to stop a USN-backed rebel movement. In Emma’s branch, however, they join the rebels to help overthrow the DHZ’s government. The events and conflicts in FRONT MISSION 3 are rarely clear-cut, and many characters who are bitter enemies in one branch become close friends and allies in the other, making it difficult to say for certain which sides are in the right. It also ensures that players will need to complete both branches in order to fully understand the story, significantly increasing the game’s replay value.

FIGURE 9.4

Different characters join Kazuki’s party depending on which choices the player makes. © Square Enix, Co., Ltd. All rights reserved.

In addition to the single major branch, FRONT MISSION 3 makes use of various moderate and minor branches as well. An example of a moderate branching point occurs when Kazuki’s forces are tasked with assaulting an army stronghold in Emma’s story. The player can choose to either break in through the front (a difficult but very direct route) or sneak in through the mountains (a longer but far safer option). Aside from the different sets of battles, the choice determines whether Kazuki will eventually recruit Jose or Li to join him. The main plot remains the same either way, but both characters have their own specialties, backstories, goals, and opinions on the events taking place throughout the rest of the game. Finally, many minor branches are spread throughout the game. These branches generally revolve around which route or strategy the player decides to adopt in certain situations and change little other than one or two battles (and the events surrounding them). Some, however, are determined by whether the player is able to complete certain goals in battle (such as destroying an enemy transport before it escapes). Though the effects of these branches aren’t long-lasting, they increase player freedom in what is otherwise an extremely linear game and provide enough variety to mix things up a bit and further increase replay value.

FRONT MISSION 3’s branching path structure allows the player to have a moderate degree of control over the progression of the plot while still telling a deep and well-structured story. In addition, the way its different branches focus on characters and situations on both sides of conflicts greatly expands on the story and setting, giving players a much broader perspective than they’d have in an interactive traditional or multiple-ending story. The only notable flaw in the game’s story structure is that the decision at the major branching point seems so minor that players could easily underestimate its importance and put away the game after a single playthrough, never realizing that they’re missing an entire half of the story.

Deciding Where to Place Branches

As with endings, have your story’s basic concept and structure planned out before you start adding decision points and branches.

Minor branches are the easiest to add. Look for places in the story at which the hero will face a decision that won’t have a serious impact on the main plot. Conversations are a good place to put them, as you can let the player steer the subject toward the matters that interest him or her most or allow the player to approach a topic in several different ways (kind, rude, crafty, etc.). Battle strategies such as deciding to sneak past or engage enemies are also a good place to work in minor branches, though the exact method will very heavily depending on the type of gameplay and battle system in your game.

Moderate branches require a bit more forethought. A good set of moderate branches should be placed at a point in your story where they can safely split off from the main branch for a while – only to rejoin it later. Giving the player a choice between two alternate routes to the same destination (taking the long route over the mountains or the short dangerous one through the caves) works well, as does providing multiple ways to approach a certain goal. For example, if the hero needs an artifact that is owned by a very rich man, you could provide a choice between sneaking into the man’s manor and stealing it, performing a task for the man in return for the artifact, or earning enough money to buy it outright. All three of those options would take a decent amount of time and bring the hero into contact with different characters and situations, but they’d all eventually rejoin once he gets the artifact.

As major branches are the biggest and most important ones, their placement needs to be approached with the most care. First, you need to identify points in your story where a certain decision or action on the part of the hero has the potential to wildly change the plot. Next, you should think about what the key differentiating factor between each major branch should be. In Front Mission 3, it’s who Kazuki ends up working with to stop MIDAS (Alisa or Emma), while in Fate/Stay Night (which we’ll discuss a little later on) it’s which girl Shiro falls in love with (Saber, Rin, or Sakura). Naturally, there’s far more that differentiates the major branches than that, but these key factors begin a series of events that go on to affect the entire story. Although romances and alliances are two common key differentiating factors, other possibilities include the choice between good and evil, whether certain characters live or die, and which hero becomes the “main character.” Once you have your key differentiating factor in mind, take another look at your list of potential branching points and narrow it down to ones that fit well with the types of stories you want your major branches to focus on. For example, because the two major branches in Front Mission 3 are based on who Kazuki partners with, the decision point revolves around whether he arrives at the research center in time to save Alisa or comes later on, at the same time Emma is there. In Fate/Stay Night, the decision points for the major branches are tied into how Shiro acts around the three girls. So give it some thought and decide which potential branching points best support your major branches. One more interesting thing to note is that you can approach your major branch structure in two ways. The first is Front Mission 3’s method, in which players sooner or later reach a point where the story splits into two or more main branches and they have to choose one in order to continue. The second is Fate/Stay Night’s method, in which there is a “default” main branch (Saber’s) and any additional main branches can be reached only if players fulfill certain specific conditions doing the first part of the default branch (in Fate’s case, that means saving Rin from Saber or being especially nice to Sakura).

There’s one final thing you should consider when planning each of your branches. What does this branch add to the story? Branches do exist to give the player choices, but if those choices lead to uninteresting results, you’re more likely than not to bore the player rather than engage him or her. Branches can provide a different perspective, different dialog, different quests, and even entirely different takes on the story as a whole, but unless a branch is interesting and/or enjoyable and at least moderately different from the other potential branches, it should be left out. If you have a decision point with three branches and only two of them lead to interesting scenarios, you can expect at least a third of your players to miss out on the interesting parts and be forced to slog through a dull and boring section. This is especially important with major branches. Although players can forgive some boring minor or moderate branches, because they’ll end and rejoin the main branch sooner or later, a major branch significantly changes the rest of the game, so it’s critical that each one provides an experience that’s fun and interesting enough to keep players entertained until the end.

How Many Branches Should a Story Have?

As with endings, there’s no hard and fast rule as to how many branches you should put in your story. If you followed the instructions in the previous section and put together a list of potential decision points and branches, you should have an idea of just how many branches your story can potentially have. However, you’ll probably want to reduce that number a bit. First, as we just discussed, get rid of any branches that don’t provide interesting and/or enjoyable additions to the story. Then look at your abbreviated list and start thinking about your production schedule. As mentioned in the last chapter, every additional ending you add to your story takes extra time, effort, and money to write, model, code, and so on. Branches are the same. Minor branches are usually fairly quick and simple to create (though this can vary considerably based on their exact content), but the longer and more unique a branch is, the more work is required to create it. Moderate branches naturally take quite a lot more work to create than minor branches, but they can’t even begin to compare with the time and effort required to create additional major branches, especially as each major branch will need its own set of minor and moderate branches. You’ll be able to reuse some material across multiple branches (the game engine, certain areas and characters, etc.), but the time and cost needed to add extra branches still grows very quickly. With that in mind, it’s a good idea to consult with the lead designer and/or producer (unless you yourself are filling one or both of those roles), review your schedule and budget, and then go over your list of potential branches one more time and remove everything except for the best and more important ones.

We talked a little bit about Japanese visual novel games back in Chapter 7 during the case study of Higurashi: When They Cry; now it’s time to explore the genre in a bit more depth. Visual novels (or sound novels, as they’re sometimes called) are a popular game genre in Japan. They’re primarily released on the PC, but many titles are later ported to consoles such as the PlayStation 2 and DS. Due to their relatively low production costs, visual novels are generally created by small teams of independent game developers. They often begin as hobby projects, with their creators later going on to form official development studios if their first game proves successful. The most popular visual novels frequently spawn anime (animated television series), manga (comic series), and massive amounts of merchandise – including soundtracks, figurines, and much more – with some visual novel developers such as Type-Moon and Key becoming extremely successful.

Despite their popularity in Japan, only a handful of visual novels have been released outside the country, and most of the more popular ones, such as Type-Moon’s Tsukihime and Fate/Stay Night and Key’s Kanon, Air, and Clannad, have yet to be released outside Japan. There are numerous reasons for this, including the small independent nature of most visual novel developers, worries about translation accuracy, concerns about how Western gamers will react to the gameplay style, the adult content found in some visual novels, and a general misunderstanding of the American market by many people in Japan. Though the situation is slowly improving, it’s hard to say if we’ll ever see official English releases of the vast majority of visual novels, which is highly unfortunate because they contain some of the best branching path stories in gaming.

Though most visual novels aren’t released outside Japan, there are a few available from MangaGamer (http://www.mangagamer.com) and JBox (http://www.jbox.com), though it should be noted that JBox specializes primarily in adult-oriented dating sims rather than visual novels and that a large portion of MangaGamer’s catalog is also made up of highly adult-oriented titles rather than story-focused ones.

If you can’t read Japanese but want to try out some of the more popular story-focused visual novels such as Fate/Stay Night and Kanon, there are some fan-made translation patches available online that can be used with the Japanese retail versions of the games. Though importing the games and tracking down the correct patch takes a bit of work, it’s currently the only way people without advanced Japanese skills can experience these excellent stories.

Note that although anime and manga adaptations of some popular visual novels have been released in the United States, they contain highly abbreviated versions of the original stories, often losing much of their depth and leaving lots of unresolved plot threads.

So what exactly is a visual novel game anyway? A visual novel is a type of game that is in many ways similar to reading a book. The story is told through large blocks of text, generally written in a first-person perspective from the main character’s point of view. However, unlike e-books, visual novels contain background images that change based on the hero’s current location and facial and/or full-body portraits of any character or characters he’s talking to. The artwork usually isn’t animated, but each character has enough poses that he or she still appears to be reacting accurately to the situation. The text and visuals are further complemented by a full set of sound effects and background music and, in some games, voice acting. This turns what would be an e-book of sorts into a full audiovisual experience – hence the term “visual novel.”

But where does the game part come in? Visual novels (with a few rare exceptions such as Higurashi: When They Cry) use branching path stories. On the surface, they’re fairly similar to those found in Choose Your Own Adventure books. Every so often, the player will be presented with a choice, with the story branching accordingly depending on his or her decision. Also similar to the Choose Your Own Adventure formula, it’s quite common for many wrong choices to lead to the hero’s unfortunate demise, forcing the player to back up and try again. However, the branching path stories in visual novels represent significant improvements over those found in Choose Your Own Adventure books. First, some decision points are hidden from the player, with the game automatically selecting a branch based on the player’s past decisions. For example, in one part of Fate/Stay Night the hero, Shiro, is seriously injured and close to death. If, over the course of the game, he was friendly enough to Ilya (a mysterious girl he encounters at various points), she’ll come to his rescue. If not, he’ll be left to fend for himself. Things like that would be far more difficult to track in a physical book. Other features, such as a large number of save slots and the ability to rapidly skip through sections that have already been read, make it easy for players to fully explore the story and try out all the different branches. But most importantly, being a digital product, visual novels don’t face the length restrictions found in physical books. When taking into account all of Fate/Stay Night’s different branches, the total word count is more than that of the entire Lord of the Rings trilogy. A book of that size would be huge, and the need to constantly flip through the pages to follow different branches would make it a chore to read. However, this significant increase in length allows visual novel games to tell stories as long and complex as those found in any good novel while still using a branching path structure. The focus on deep stories with mature themes and consistent plots throughout all the branches further sets them apart from Choose Your Own Adventure books.

If you’re interested in exploring the world of visual novels, it should be noted that there’s a rather large subgenre that is based around hentai (adult) games. These visual novels focus far more on the adult elements than on the story and can be highly pornographic in nature. Even a lot of the story-focused visual novels such as Fate and Kanon tend to contain a few token sex scenes (just as R-rated Hollywood movies do). But because these scenes generally have little to no importance to the main plot, they can be skipped over without consequence. Quite a lot of story-focused visual novels are also released in two versions: a regular, unedited one and an “all ages” edition that is nearly identical except for the removal of the sex scenes. Kanon All Ages and Fate/Stay Night Realta Nua are two examples of these “all ages” editions.

Case Study: Fate/Stay Night

| Developer: | Type-Moon |

| Publisher: | Type-Moon |

| Writer: | Kinoko Nasu |

| System: | PC |

| Release Date: | January 30, 2004 (Japan) |

| Genre: | Visual Novel |

Fate/Stay Night is one of Japan’s most popular visual novels – a position it’s managed to hold throughout the years since its release, thanks in part to an anime, manga, movie, novel series, several spin-off games, and a variety of related merchandise. But the most important reason behind Fate’s continuing popularity is its intriguing story and memorable characters.

Fate’s story spans a two-week period of time known as the fifth Holy Grail War. The Holy Grail War is a contest of sorts in which seven magi each summon a Servant (powerful familiars based on heroes of legend such as Hercules and Gilgamesh) and fight to the death for the right to control the Holy Grail, a magical relic with the ability to grant any wish. This particular Holy Grail War is unusual, having begun decades ahead of schedule.

Before the war, Shiro Emiya is a seemingly ordinary Japanese high school student who lives on his own after the death of his guardian, Kiritsugu (who rescued the young Shiro from a devastating fire ten years before). Unknown to those around him, Shiro is also a mage, albeit a very weak and inexperienced one. He learned the basics of the art from Kiritsugu before his death, but never received full training; he can do little other than slightly strengthen various objects. Though disappointed by his lack of progress, he continues to practice in hopes of realizing his dream of using the art to help others, becoming a sort of superhero. Although he knows nothing of the Holy Grail, Shiro’s life is turned upside down when a strange twist of fate puts him in control of Saber, a young woman and master of the sword who is rumored to be the strongest Servant of all. Shortly after, he saves the life of Rin Tosaka, a classmate who is heir to a prestigious family of magi and Master of the Servant Archer. In thanks, she tells him about the Servants, the Grail, and the war. Though Shiro has no interest in the Grail or fighting, he agrees to join in order in protect the townspeople from the other, far more ruthless, magi who are competing.

The story quickly grows far more complex. All Masters and Servants have their own reasons for seeking the Grail, many of which belie dark troubled pasts. Shiro’s determination both to not kill and to protect everyone, along with his lack of magical skills, puts him at a serious disadvantage. Even though Rin and Saber see his ideals and dream as foolish, Shiro defends them to the end, determined to die rather than betray them. Meanwhile, Saber is wrestling with her own past, which is tied into the heroic identity she keeps hidden from everyone, Shiro included, and is desperate to find the Grail so that she can correct her greatest mistake. And that’s barely scratching the surface. Fate’s tale is shocking, emotional, and often very dark, grappling with issues including murder, rape, loyalty, betrayal, and the morality of sacrificing a few to save many.

As previously mentioned, Fate’s English fan translation contains more words than the entire Lord of the Rings trilogy, spread over three major branches and numerous minor and moderate ones. Though many branches lead to Shiro’s untimely demise, finding every bad ending is actually a worthwhile pursuit in and of itself, as they’re followed by humorous scenes featuring the other characters discussing what Shiro did wrong and offering hints on what to try next time, while also unlocking special bonus content. There are forty bad endings and five full endings (one on Saber’s branch and two each on Rin and Sakura’s), and because the correct choice isn’t always the one that seems most logical, it’s impossible to completely avoid death. Fortunately, the ability to save at any time and rapidly skip over completed sections of the story makes it easy to experiment and try different options.

The three major branches – dubbed Fate/Stay Night, Unlimited Blade Works, and Heaven’s Feel – each tell a very different side of the story, and it’s impossible to understand everything that’s taking place behind the scenes in the Holy Grail War without completing each one. Despite retelling the same basic story, each major branch is considerably different, focusing on different characters (both friends and enemies) and showing vastly different ways in which the story could play out. Fate/Stay Night is Saber’s story, the default main branch, and the one that players have to complete first. It focuses on Shiro and Saber’s backstory, while introducing players to the Holy Grail War and many of the important characters. Completing it opens up the decision point leading to Unlimited Blade Works, which focuses on Rin and Archer while also delving deeply into Shiro’s motivations and the dangers of his naïve ideal. Getting either of the good endings in Unlimited Blade Works opens the decision point leading to Heaven’s Feel. It’s the longest and darkest of the main branches, with a focus on Shiro’s friend Sakura, her brother Shinji, the Servant Rider, and Berserker’s master Ilya.

Each branch tells a very important part of the story, and it’s not until after the completion of Heaven’s Feel that players will fully understand each character’s histories and motivations and the true nature of the Holy Grail. All told, finding every ending (good and bad) and following every branch (minor, moderate, and major) can easily take over 60 hours, but it’s a worthwhile investment for such a deep and multifaceted story. Although forcing the player to go through the three major branches in a predetermined order does somewhat limit player freedom, it also removes the need to reiterate the same character introductions and exposition in each branch, which prevents players from getting bored by repeatedly rereading the same material and allows each progressive story revelation to build on the ones that came before, making the small reduction in player freedom worthwhile.

There are many games that use branching path stories well, but it’s visual novel games like Fate that show the true potential of the style first popularized in the old Choose Your Own Adventure books, allowing players to make choices and fully explore multiple aspects and perspectives of the story while maintaining well-structured plots with the depth and complexity normally reserved for far less interactive storytelling styles.

The Strengths of Branching Path Stories

As shown in the previous case studies, the greatest strength of branching path stories lies in their ability to provide players with a large number of important choices while still giving the author a considerable amount of control over the progression of the story. This allows for lengthy and complex stories with good structures and pacing (things that become increasingly difficult to control in heavily player-driven stories). Meanwhile, the interactivity itself gives players a moderate amount of control, rather than just the illusion of control present in interactive traditional stories, and allows both the player and the writer to explore many different aspects and alternate tellings of the story. Though they don’t give the writer complete control and lack the ease of creation found in interactive traditional stories, while also lacking the larger degrees of player freedom found in open-ended stories and fully player-driven stories, a well-done branching path story strikes an excellent balance between player freedom and a well-structured plot. Despite their shortcomings, in many ways they form the best possible combination of both sides of the storytelling spectrum.

Case Study: Heavy Rain

| Developer: | Quantic Dream |

| Writer: | David Cage |

| Publisher: | Sony Computer Entertainment |

| System: | Sony PlayStation 3 |

| Release Date: | February 23, 2010 (US) |

| Genre: | Adventure |

Though best known for their recent PS3 hit Heavy Rain, developer Quantic Dream also created the cult classics Indigo Prophecy and Omikron: The Nomad Soul, both of which are known for their excellent stories. Thanks to its realistic graphics, emotionally charged story, and a strong marketing campaign, Heavy Rain’s success has greatly exceeded expectations, finally bringing Quantic Dream’s name into the public eye.

Part adventure game, part interactive film, Heavy Rain takes place in an unnamed American city and follows four characters in their attempts to discover the identity of the illusive Origami Killer, a serial killer who abducts and then drowns young boys. Ethan Mars is an architect who lost his oldest son in a traffic accident two years prior. He never got over the tragedy, causing him to become estranged from his wife and younger son, Shaun. However, when Shaun mysteriously disappears and all signs point to the Origami Killer, Ethan puts everything on the line to get him back. His chance encounter with Madison Paige, a newspaper photographer with a serious case of insomnia, leads her to aid him and begin her own investigation into the killer’s identity. Meanwhile, the Origami Killer is also being pursued by Scott Shelby, an aging private eye hired by the victims’ families, and Norman Jayden, an FBI profiler working with the local police.

Though the four characters’ stories frequently intertwine, they never actually team up, with each pursuing his or her own methods of finding the killer and the game switching between characters at the start of each chapter. The gameplay itself is a mixture of standard adventure fare (conversing with other characters and engaging in some light puzzle solving) and extended quick time events (scripted cut-scenes in which the player frequently has to push certain buttons to help the hero succeed in whatever he’s doing). Despite the use of a PS3 controller, the button combinations used in these scenes do a good job of representing what the character is physically doing, whether it’s firing a gun or gently rocking a baby to sleep. The addition of support for Sony’s new Move motion controller helps to make these events even more realistic. One of the most unique aspects of Heavy Rain’s gameplay is that regardless of whether the player successfully hits all the button prompts, the scene will continue, with the events changing based on the player’s success or failure. Though quick time events have become commonplace, especially in action games, failure to hit the proper button usually results in the event failing, forcing the player to restart it. But Heavy Rain keeps going, no matter what. Even if one of the heroes dies an early death, the story will continue on without him or her.

Despite suffering from a few plot holes, Heavy Rain’s story manages to be emotional, profound, and disturbing. It draws players in like few other games, making them strongly feel Ethan’s desperation as he pushes through a crowded mall calling out to his missing son and Madison’s shame when a sleazy night club owner forces her at gunpoint to perform a private striptease act. It also brings up a large number of interesting moral dilemmas. Shortly into the game, Ethan is given a set of challenges by the Origami Killer that he must complete to receive clues to Shaun’s location, all in the name of seeing just how much he’s willing to sacrifice to save his son. Early challenges test Ethan’s bravery and willingness to risk serious injury; some of the later ones become true tests of Ethan’s and, by extension, the player’s beliefs and convictions. As discussed in Chapter 3, one challenge tasks Ethan with killing a man. Although Ethan is desperate to save Shaun, seeing his intended victim kneeling at his feet begging for a chance to see his own child again gives him serious second thoughts. Later on, the final challenge presents Ethan with a vial of deadly poison that when drunk will kill him in one hour, leaving him just enough time to save Shaun and say his final goodbye. Ethan is free to back out of any or even all of the challenges, and it is possible for him to find and save Shaun without completing all of them, but that’s something that neither Ethan nor the player knows at the time, making each decision a matter of life and death and leading to a lot of interesting discussions among players about what they would choose if faced with a similar situation in real life. The game’s last major plot twist, involving the unmasking of the Origami Killer, is another shocking scene that has led to an enormous amount of discussion and makes for an emotionally charged lead-up to the final confrontation and ending.

The sheer number of reactive events and the way they match the players’ actions, rather than forcing players to retry them until they do it right, create an incredibly strong sense of control, making players feel as if their every decision and button press matters. Unfortunately, playing through the game additional times shatters this illusion, as players will soon realize that most things they do actually don’t have any effect on the story beyond the current chapter – and even then, the effect is often minimal. Most branching points are minor, with only a couple moderate branches and one major one. That isn’t counting the branches that take place if players allow one or more of the heroes to die or fail in their search, as keeping them alive and on the right track is surprisingly easy (with numerous chances to recover from poor button presses and faulty leaps in logic), and even if they do die, their remaining story scenes are merely dropped from the rest of the game, with the only significant change to the rest of the story being the events of the final chapter and the ending scenes the player receives. To some extent, this is a good thing, as it allows the story to retain its tight pacing and careful structure. However, players may be somewhat disappointed upon discovering that the game doesn’t quite live up to the “everything you do matters” hype. Regardless, its emotional story and unique gameplay make Heavy Rain one of the most interesting and innovative games in years. The replay value is questionable, but this player’s first playthrough was an extremely engaging and exhilarating experience and the shocking scenes and difficult moral decisions are sure to remain on players’ minds long after the credits roll.

The Weaknesses of Branching Path Stories

Branching path stories are in many ways an excellent synthesis of the structured plots of interactive traditional stories and the freedom of more player-driven forms of storytelling, but they’re not without problems. The first is their creation process. As you probably realized when reading through this chapter, planning out all the different branches and decision points and ensuring that each one is interesting and serves a purpose in the overall story isn’t easy. If you haven’t realized that yet, just give it a try for yourself and you’ll soon see what I mean. And, as previously mentioned, the more branches you add to a story, the more time and effort (and, by extension, money) it takes to complete. This can be somewhat negated by creating shorter stories and/or reusing a lot of assets, but some players will be annoyed by short stories (regardless of how many branches they have), and reusing too many assets can lead to your main branches feeling overly similar, which is sure to bore many players.

The structure itself also shares a problem with multiple-ending stories, namely, a potential loss of impact. Important story events such as the hero’s failure or the murder of an important character lose quite a lot of their emotional impact when players know that they can just reload from an earlier save and take a different branch in order to prevent it. After all, what’s a death or crushing defeat when you can just turn back time and pretend that it never happened? You can avoid this result entirely by making your more emotionally charged moments unchangeable, though that may leave some players wondering why you bothered giving them choices in the first place if they can’t change some event. Or you could place the branching points that influence those events long before the actual event takes place, so that the player won’t be so quick to jump back and try out a different branch, though this only lessens the problem and doesn’t remove it entirely.

Another potential problem lies in the fact that it’s not always easy for players to tell what the results of their decisions are going to be before (and at times even after) the fact, such as Kazuki’s delivery decision in Front Mission 3. In cases like this, players may end up on a branch they don’t like with no idea of what wrong choice sent them there. This can lead to quite a lot of frustration, especially if a player needs to replay a significant portion of the game in order to turn the story down a more enjoyable branch.

Finally, branching path stories tend to require players to complete most – if not all – of their different branches before they can fully understand the story. Though this is fine for hardcore players who are determined to thoroughly explore every nook and cranny of their games, it’s important to remember that many players will play through a game only once or maybe twice and may never see quite a lot of the branches that you put so much time and effort into creating. This raises the question of whether adding all of those branches is really worth the effort – something we’ll discuss more in Chapter 13.

Case Study: THE BOUNCER

| Developer: | Square Co., Ltd. |

| Publisher: | Square Electronic Arts LLC |

| Writers: | Seiichi Ishii, Kiyoko Ishii |

| System: | Sony PlayStation 2 |

| Release Date: | March 5, 2001 (US) |

| Genre: | Beat ’Em Up |

FIGURE 9.5

At the beginning of every battle, the player can choose to play as Shion, Volt, or Kou. © Square Enix, Co., Ltd. All rights reserved.

Square’s first PlayStation 2 game was a large departure from the epic RPGs that made them famous. Though the graphics, music, and voice acting are generally well regarded, the story and gameplay drew very mixed responses from fans. For starters, THE BOUNCER is short, with a single playthrough requiring only several hours at most. There’s also very little exploration and only light RPG elements, with the game mostly made up of cut-scenes and FMVs interspersed with beat ’em up–style brawls.

The story revolves around Shion, Volt, and Kou, three bouncers working at a bar named Fate, and Dominique, a teenage girl whom Shion took in after finding her wandering the streets alone in the rain. At the start of the game, Dominique is kidnapped by a group of strange ninja-like assailants, causing the three friends to run off in pursuit. Their journey leads them to the powerful Mikado Corporation and its cruel and calculating CEO Dauragon, and eventually into space for a final showdown. The plot has a strong Hollywood action movie vibe with lots of fast scenes, chases, explosions, and battles against increasingly strange and powerful martial artists. As such, it’s a lot of fun and has a couple of genuinely interesting twists, but also gets a bit ridiculous at times (thanks to things like the space flight and Dauragon’s assistant, a woman who can transform into a panther).

FIGURE 9.6

THE BOUNCER has a strong action movie vibe. © Square Enix, Co., Ltd. All rights reserved.

The most interesting aspect of THE BOUNCER’s story is the way it uses branching path storytelling. At the beginning of each battle, the player is given a choice of which of the three bouncers to control directly, with the others being handled by AI. Only the chosen bouncer receives stat boosts and new attacks from the battle, and the subsequent cut-scene is also told from that particular character’s perspective. For example, after the opening brawl, Kou calls someone on his cell phone to help track down Dominique’s kidnappers. If the player chose Shion or Volt, he hears only Kou’s side of the conversation; players who chose Kou get to hear both ends. Almost all of these constitute minor branches, with only a couple of moderate ones when the three heroes split up for a short time. However, players need to play through the game at least three times in order to learn all about Shion, Volt, and Kou’s pasts and their connections with the Mikado Corporation. The only real major branch occurs at the very end of the game and determines, along with their decisions at some earlier minor branches, which ending the player will see.

Although being able to play the story from three different perspectives is interesting and significantly increases the replay value, each character’s path is extremely similar, making those replays feel somewhat repetitious. Players who are put off by this, or who simply don’t have the time or inclination to play through the game multiple times, will also miss out on quite a lot of important story elements, including the heroes’ backstories and the identity and motivations of enemy characters such as Kaldea (the panther lady) and Echidna (a Mikado employee who has a history with Volt). Some players enjoyed having lots of incentives to play through the game multiples times; others strongly disliked having to replay it so many times to fully understand the story, especially as each character’s path is so similar. In the end, although THE BOUNCER remains a fun and enjoyable game, it also exemplifies some of branching path storytelling’s inherent problems.

Branching path stories use a structured, writer-controlled story combined with a number of decision points and branches to provide players with a degree of control over the direction and progression of the plot, a style first popularized in the Choose Your Own Adventure books. Though most branches are minor or moderate and stray from and/or alter the main branch for only a short period of time, major branches break away completely, creating new main branches of their own and taking the story in entirely different directions.

Deciding where to put your decision points and branches can be difficult and takes a lot of planning, as does ensuring that the story remains interesting and enjoyable no matter what choices the player makes. The additional amount of time, effort, and cost needed to create each branch is also a very important factor, especially considering that many players complete a game only once or twice and may never see quite a lot of the branches.

When done correctly, branching path stories can create an excellent combination of well-structured, writer-controlled plots and player freedom – something that is demonstrated especially well in Japanese visual novel games. However, they can suffer from a loss of impact similar to that found in multiple-ending stories. There’s also the danger that players will become upset if they get struck on a branch they don’t like or have to replay the game too many times in order to fully understand the story. This is especially problematic if the different branches use too many of the same elements, making them feel overly similar. Despite this danger, branching path stories still remain one of the most promising forms of player-driven storytelling.

1. List five games you’ve played that use branching path stories (if you haven’t played that many, just list the ones you have).

2. Pick two of the games from your list. Make a simple flowchart of their branching structure, using a strategy guide or online FAQ as a reference (if the games are really long, chart out only a portion of them). Mark each branch as minor, moderate, or major.

3. Pick one of those two games. Are there any branches that you consider to be boring and/or unnecessary? Explain your reasoning for each of those branches.

4. Did the presence of the different branches make you want to replay the game so that you could see the other outcomes? Why or why not?

5. Do you think the use of a branching path structure significantly enhanced or detracted from the game’s story? Explain your reasoning.