CHAPTER

Four

The Story and the Characters

Having your story idea and structure all planned out is a great start, but when it comes to good storytelling in games or any other medium, what really makes a story great isn’t the basic idea or the structure –it’s the details. With smooth pacing and an interesting cast of believable characters, even a generic or seemingly dull idea can make for a great story. Unfortunately, the opposite is true as well. Characters that are boring or that the players can’t relate to can quickly suck the life out of even the best story idea, and poor pacing will turn large sections of a game into a tedious slog, no matter how good the story itself is. Neither of these issues alone will completely ruin a story, as long as the rest of the elements are done well, but failing in just one of them can mean the difference between creating a good story and a great story. Just as pacing and characters are individual elements of the whole story, the story itself is a single element of the game, and failing in even one element can be the difference between making a good game and making a true masterpiece. If you want to be a great writer, you need to make sure that every element is in place, even the small ones.

The Importance of Proper Flow and Pacing

A story’s pacing can be compared to the flow of a river. Big twists and exciting events are like rapids or fast-moving sections; parts of the story in which the characters relax or engage in unimportant activities can be thought of as slow, calm sections. For proper pacing, you need both fast areas to excite players and keep them interested and slower sections in which you can focus on character development and give the player a chance to unwind. Game designers know that gameplay pacing works in much the same way. If your pacing is constantly fast and furious, players will get worn out by the endless barrage of information and won’t have time to take it in or calm down; you also won’t have the time to adequately develop your characters and their worlds. But if your slow sections stretch out too far, players will grow bored and wonder when things will get interesting again. A fine level of balance is needed to ensure that the pacing never becomes too slow or too fast. Though perfect pacing is very difficult to achieve, adequate pacing is a must if you want players to stay interested in your story.

The Interest Curve

Writers kick around terminology like “act break,” “increasing tension,” and “climax,” but the thing that is sometimes tough to remember is that the story runs by the audience in a continuous stream of emotional response (that is, hopefully the audience is responding, eh?) and that you are architecting that response moment by moment, beat by beat, scene by scene, sequence by sequence, and act by act. There’s a whole universe of moments, all of which need to contribute to generating the emotional response. The “pace” that Josiah is talking about is that back-and-forth of the contrasts inherent in these moments. In Jesse Schell’s book The Art of Game Design, he talks about a phrase in game design (well, actually, entertainment design) called the “Interest Curve.” This phrase is used to describe (wait for it …) the moment-by-moment design of the game wherein the player gets whip-sawed back and forth through contrasting loud and quiet, exciting and reflective, and angry and loving moments (for example). The point is that, indeed, those wonderfully exquisite game moments are created through the identical method that writers use to architect our classic stories. At other points in this book, you’ll hear me say that writing great stories uses the same skills as game design, and it is mainly due to this singular fact.

I was trained as a playwright by a great teacher, Milan Stitt. He would talk about classic story structure as a five-act emotional journey. Act I is what you’d expect, the send-off into the story and the implantation of the Major Dramatic Question (MDQ) into the mind of the audience. In fact, the moment when the audience could articulate what that question is would be described as the end of Act I. The ends of Acts II, III, and IV occur when the story becomes much more difficult for the hero through a series of increasingly difficult complications, and indeed the hero must alter his or her plan (example: in Raiders of the Lost Ark, think of the end of Act II as when Indiana discovers the Ark [the MDQ being, until that point, “Will Indiana find the Ark before the Nazis do?”] only to lose it to Belloq. Act II transitions into Act III, with the MDQ being, “How will he get it back?”).

Those complication points in a five-act structure add tension and make it more difficult for our hero to get to his or her goal.

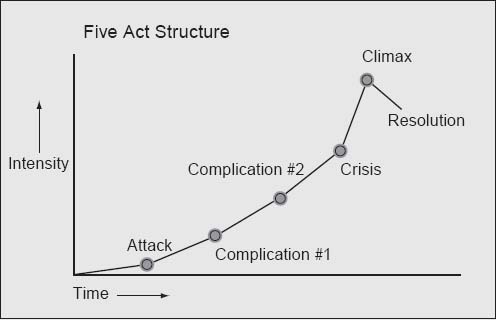

A diagram of the five-act structure is shown in Figure 4.1.

FIGURE 4.1

Five-act story structure.

This diagram depicts the “interest curve” for the story. One of the most telling aspects of storytelling is the idea that not only do overall stories follow this structure, but so does every scene, every act, and every sequence. This point is so crucial to understand that I cannot emphasize it enough. When you write a scene, it must have an attack, a complication, a crisis, and a resolution. This all comes from the way you have set up the scene, and the conflict you have built into that setup.

One last comment on this note: a great visual depiction of the way interest curves work in cinematography can be found in Bruce Block’s book Visual Story.

—Chris

As with endings, creating good pacing is something of an art form that can’t entirely be taught. If you still have trouble grasping the concept after reading the rest of this chapter, try looking at the stories in some of your favorite books, movies, or games and think about how they flow between big events and smaller, more subdued moments. If there are any parts that seem to drag on for too long, make note of them as well. Before long, you should have at least a general idea of how to pace your own stories.

To Learn Story, Deconstruct It

If this idea of structure confuses you (and, at first, it probably will, because we’re so trained to look at the actors and listen to what they say that we perceive story as happening through and about the characters), here’s the best way to learn: pick a writer whose work you really admire. Choose someone who’s not just a one-hit wonder, but someone who has repeatedly proven that he or she can write more than a little bit. Sit down with that writer’s work (if it’s a TV writer, for instance, get his or her shows’ DVDs) and get to know your remote control intimately by working your way through at least three of his or her episodes. Be certain that this writer wrote the episode you’re watching. Watch each episode once through, so that you get familiar with the storyline. Then start the episode over again, and describe each scene as it goes by, stopping the DVD as each scene ends to summarize the events. You should also note the length of each scene, because in a time-bound medium such as TV, the length of a scene is as crafted in the final cut as the dialog. If you’re watching carefully, you should also note the conflict in each scene, and also how the conflict is resolved. By the end of the episode, you’ll have a roadmap to the story. Then draw yourself a little graph like the previous one, noting the high points and low points. Perform this exercise for three episodes. You’ll learn so much about the way that writer thinks about story, how he or she sets up reversals, and so forth. In effect, you begin to assemble a list of all the “bullets” that writer carries around in his or her gun. When you do that, you’ll begin to understand how you react as an audience member, and how that writer has pushed your buttons so successfully.

—Chris

Don’t Neglect the Little Things

When you’re writing a story, it’s tempting to want to jump from big moment to big moment without putting much of anything in between. When you’re a writer, it’s quite common for certain parts of a story to excite and interest you more than others, but it’s something you need to be wary of.

To give a simple example, let’s say you’re working on the story for a modern-day crime game. You’ve already got the structure laid out and you’re ready to go. You’re going to open the story big, with an epic car chase when a routine heist goes wrong, and you’ve got an exciting ending planned around a complex robbery in a Las Vegas casino. Between those two events, you also want to feature a clever museum heist, another car chase (because, as Hollywood has taught us, you can never have too many car chases), and a tense game of cat-and-mouse between your hero and some federal agents set in a large office building. These are your key scenes and the things you’re building the entire story around. You’ve got great plans for them and are sure that the players will love them as well. Nothing wrong with that. But because all those heists are so big and fantastic, you don’t want to slow things down and write about all the planning, reconnaissance, team recruit-ment, and the like that takes place between those scenes. This is where you can run into problems.

Sure, the heists may be cool and exciting, but if you want the story to be something that players care about rather than just a vague backdrop for the action, you need more than that. You need to show the players who your characters are, what their personalities are like, and why they’re so set on robbing these places. Maybe the thief is a cop who lived an honest life but is being forced to commit these crimes by a shadowy cartel that kidnapped his daughter. You could sum that up in a line or two of text, like I just did, but that’s not going to make players feel much sympathy for the guy. If you want the story to hit home, you need to get into the details. For example, you could put in some flashbacks of the guy and his daughter before the kidnapping.

The Problem with Flashbacks

Flashbacks are tricky, because one thing you need to do in drama is keep the story moving forward. If the flashback contains only setup information (information that might be better served by integrating it into the story), you will find that after you’ve returned to the drama, it can feel as if that was a waste of a few minutes. However, artfully done flashbacks can work, as long as they contain information that is crucial to the successful resolution of this story (Frodo needs to bring the Ring to Mount Doom to be destroyed because that is where it was created, so telling the story of the Ring’s creation isn’t just fluff – it’s a crucial piece of information). Following is an example of the best way to handle backstory (dialog is approximate).

In the pilot episode of The West Wing, there is a scene in Act I in which we find out why Josh’s job is in jeopardy. It turns out that on national TV, he made a cheap joke to a member of a conservative Christian organization. The scene opens with Josh watching a tape of the quote playing over and over. His assistant, Donna Moss, enters his office with a cup of coffee. Remember, this is the pilot episode, so the writer, Aaron Sorkin, needs to not only tell the story, but also introduce all the main characters to give you a little sense of their history.

So Donna enters with the cup of coffee, Ordinary, right? Not so much.

Donna enters with the coffee, and Josh says, “What’s that?” Donna says “I brought you a cup of coffee?” Josh says “What?” Donna says “Coffee.” Josh replies “Donnatella Moss, how long have you worked for me?” “Four years.” “And in that time, how often have you brought me a cup of coffee?” She looks down at the coffee. “Why do you ask?” she says. Josh persists: “How many times?” She stammers a bit, “Well …” Josh pushes further: “I’ll tell you how many times. None.” She is caught red-handed. “Never,” he continues. “You’ve never brought me a cup of coffee. Donna, if I get fired, I get fired.”

So what Sorkin masterfully does is use a prop to do multiple things. First, it allows him to show that Donna is really worried about Josh. Second, it allows Sorkin to tell a little of the backstory about their relationship in an organic way without either character launching into a dreary sort of “back when we were working on the campaign” speech. And third, the revelation moves the story forward because now we know Josh is aware of how dire his situation is.

—Chris

Perhaps the girl was rebellious and the two really didn’t get along, even though he loved her and tried his best. Maybe she was kidnapped right after they had a big fight and never having apologized is tearing him up. The way he goes about planning and preparing for the heists can also show a lot about his personality and that of the people he works with. Because he’s a good cop, having to commit crimes could very well be destroying him on the inside, causing him to question his entire life and beliefs, and changing the way he relates to others. These are the kinds of things you need to show if you want to really draw players in. Similarly, if your story takes places in a really interesting world or location, players are never going to have the chance to explore or learn about its culture and history if you’re just jumping from big scene to big scene. Sure, the key scenes are important, but in the end, it’s the details that really make a story special.

As previously mentioned, it’s important to maintain player interest throughout the game by using good pacing. Part of the way to do that is by making sure to spend time on the details to help players get to know and care about your world and characters. But you also need to make sure that the really interesting stuff – plot twists, big reveals, and story scenes in general – is placed regularly throughout the game. Though you don’t necessarily need a big epic scene taking placing every hour, you probably don’t want the player to go for an hour or two without any story elements, either (keep in mind that we’re assuming the player is playing through the game normally and not stopping to kill extra monsters, play cards, or do other optional activities). To keep players interested in the story, you need to keep the story moving. Moreover, although every story scene doesn’t need to drive the main plot forward, it should still be interesting and/or entertaining, even if you’re just bringing up a bit of trivia about the world or showing how the characters relate to each other.

Same Question, Different Day

One traditional method to keep the story moving is to morph the MDQ as you go along. When it is done artfully, audiences will view this as an organic evolution of the story rather than an abrupt change. Example: Act I of Raiders of the Lost Ark ends when Indiana takes off after the Ark and launches Act II. The MDQ at that point is: will Indiana find the Ark before the Nazis do? Note how each bit of tension in the story during Act II relates to this question: do the Nazis know more than Indy does? How could they? Indy has the medallion! Oh, wait, they’re digging in the wrong spot! And so on. Then Indiana finds the Ark, but Belloq takes it away. Complication! The MDQ morphs to “How will Indy get it back?” Chases ensue. Indiana gets it back? Oh, wait, the Germans board the boat, and they take it again. End of Act III (another complication) and beginning of Act IV. Indy is on the sub! Yeah! How will he do it this time? The Nazis have gotten the Ark to the island, where they are going to do the ceremony. Holy crap! What will he do now? He ambushes the Nazis as they head to the spot for the ceremony. How’s he gonna get it? Oh, I see, a bazooka. He’ll force them to give it up. What? He surrenders. Oh no! End of Act IV (crises) and beginning of Act V, during which the final answer is given: Indy doesn’t find the Ark before they do, but it doesn’t matter because the Ark kills the Nazis (reversal). Each morphing of the MDQ alters the story in an organic way and moves the story forward.

—Chris

The PlayStation 2 game Magna Carta: Tears of Blood provides an excellent example of how not to spread out your story scenes. Despite some problematic gameplay issues, Magna Carta contains a very interesting tale about a mercenary unit embroiled in the midst of a massive war between humans and a race of beings called the Yason. The story starts out strongly enough, with information about the war, some hints at the hero Calintz’s mysterious past, and a run-in with an amnesiac girl named Reith. Unfortunately, a few hours into the game, the story falters as Calintz’s group is sent on a long series of fetch quests that have them running all around the country to collect items needed for the war effort.

During this stretch (which can easily take players fifteen to twenty hours), the main plot all but grinds to a halt with no new information revealed about the war, Calintz’s past, Reith’s identity, or any of the other questions brought up during the first part of the game. Though a definite problem, the interesting cast of characters could have helped keep players engaged and entertained during that part of the game, making up somewhat for the lack of plot developments. Unfortunately, that wasn’t the case, either as most interactions between the heroes and other characters during that portion of the game were very short and simple, showing off none of the characters’ personalities or charm. In one particularly memorable (or perhaps unmemorable) exchange, Calintz calls a big meeting with his team just to say that the volcanic cave where they’ll be heading on their next mission will probably be hot. Magna Carta’s story managed to somewhat redeem itself in the final few hours, which feature a long series of revelations, plot twists, and interesting character interactions leading up to a very strong finish. But, as good as the last part of the game is, only the players with the perseverance to press on through the long and boring middle section are able to see it.

On the other hand, FINAL FANTASY XIII (which we’ll discuss more later in this chapter) rarely lets players go more than twenty minutes between story scenes. And although not all of those scenes contain big events or important plot points, they go a long way toward exploring the feelings and personalities of the characters and teaching the player about the world where the game takes place, making for a very strong contrast with Magna Carta’s poor pacing.

General Pacing Do’s and Don’ts

• DO space plot twists, character development, action sequences, and other big scenes fairly evenly throughout the story. This ensures that the player will never have to go too long between interesting sections.

• DO ensure that there’s time for slower sections between the big scenes. Use this time to focus on things like character development, the setting, and the backstory.

• DO analyze the pacing in popular stories and use it as a guide for your own. This is not to say that all popular stories have perfect or near-perfect pacing, but it’s important to learn from others’ mistakes as well as their triumphs.

• DON’T make your story all action all the time. Players need a break now and then and even big, high-energy scenes can get dull if that’s all there is.

• DON’T let slower sections last for too long without a big event or story revelation to spice things up.

• DON’T fill sections with pointless chatter or busywork. Even in the slower parts of the story, you should do your best to keep things interesting and/or entertaining.

• DON’T save all your big reveals and answers for a single part of the story; work them in here and there as the story progresses to keep players interested.

• DON’T add in unnecessary action scenes or slow scenes just to try and even out the pacing. If a part of the story feels tacked on or unneeded, it’s likely to hurt more than it will help.

Case Study: Xenosaga Episode II: Jenseits von Gut und Böse

| Developer: | Monolith Soft |

| Publisher: | Namco |

| Writers: | Tetsuya Takahashi, Saga Soraya |

| System: | Sony PlayStation 2 |

| Release Date: | February 15, 2005 (US) |

| Genre: | RPG |

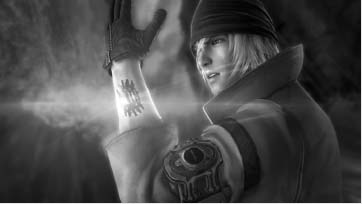

FIGURE 4.2

The heroes of Xenosaga.

The Xenosaga series is a trilogy of sci-fi RPGs on the PlayStation 2. Supervised by Tetsuya Takahashi, one of creators of the PlayStation cult classic XENOGEARS (considered by many to have one of the best stories of any video game), the Xenosaga trilogy takes place in a far future when humanity has spread across the universe. Recently, human planets and colonies have come under attack from an alien race known as the Gnosis. As Gnosis are invulnerable to most conventional weapons, a group of scientists including Shion Uzuki have created KOS-MOS, an anti-Gnosis battle android with a revolutionary, near-human AI. However, the Gnosis threat is only one of several problems facing the universe, as various cults, religions, and powerful organizations work to gain power and pursue dangerous plans of their own. Meanwhile, behind the scenes, a mysterious group of seemingly immortal figures seems to be manipulating all the different angles for reasons of their own. Thrown into the middle of this conflict, Shion, KOS-MOS, and several unlikely companions join together to fight for survival and slowly uncover the truth. Xenosaga’s deep, twisting plot earned it many fans, and though it can be a little hard to follow at times, it remains one of the best and most unique game stories to be found.

FIGURE 4.3

In the world of Xenosaga, giant robots are commonplace.

Although Episodes I and III were occasionally criticized for their long cut-scenes, they received very positive reviews overall, thanks to their enjoyable mix of on-foot and giant robot combat, memorable characters, and, of course, their amazing story. Episode II received generally positive reviews but is frequently regarded as the weakest entry in the series. Though the story was still excellent, various graphical and gameplay changes met with very mixed responses from fans. Unfortunately, the pacing was rather problematic as well. Episode II did a good job making use of both fast, action-packed scenes and slower, story-focused ones and spaced them out well throughout the game. However, many of them tended to drag on a bit too long. At many points, the player has to spend several hours fighting through dungeons with little to no plot development; in others, he or she is faced with hours of dialog and cut-scenes with no battles and very little interaction on his or her part. The cut-scenes and dialog were very well done, featuring excellent voice acting and contributing a lot to the overall plot, but much of the information revealed (particularly in the early portions of the game) – though interesting – wasn’t crucial to the main story and might have worked better if it had instead been incorporated into optional conversations and quests, thus allowing the player to get back into the action a bit sooner. Another problem – one that was probably unavoidable – is that Episode II was the middle game in the trilogy. As such, there were far fewer characters and mysteries to introduce than there had been in Episode I and, with the story far from over, many of the big revelations had to be saved for Episode III.

Fortunately, Monolith learned from its mistakes and Episode III, in addition to a host of gameplay improvements, contained excellent pacing. Story scenes were frequent, even during long dungeon crawls, and most of the technical details and less-critical information was placed in optional conversations and the in-game information database, allowing players to review it at will over the course of the game. The superb mix of action, important story scenes, and slower sections keeps players engaged throughout the game as the answers to the series’ many mysteries are revealed, finishing with a satisfying ending that succeeds in wrapping up the complex story while leaving players still hoping for more. Despite Episode II’s pacing problems, the Xenosaga trilogy is one that everyone interested in game stories should play, both for its amazing storyline and to watch the way the series progressed and evolved with each installment, as Monolith constantly strove to improve both their gameplay and storytelling.

If you look at a lot of game stories, or just stories in general, you’ll notice that many different characters have similar personality traits and roles in their respective stories. We touched on this when discussing clichéd characters in the previous chapter. Clichéd character types like the mentor, amnesiac hero, and mysterious girl are all examples – albeit rather extreme ones – of character archetypes. Simply put, an archetype is a sort of general character template that can then be customized and personalized to fit into nearly any story. To put it in game terms, an archetype is like a character class. Choosing to make your character a rogue instead of a knight or monk, for example, automatically assigns certain traits to that character. A typical rogue may be fast and agile, but he probably won’t have the defensive skills of a knight or the barehanded prowess of a monk. However, that doesn’t mean that every rogue is the same. Your rogue could specialize in bows or knives, traps or lock picking. He could be a jolly and helpful Robin Hood–like figure or a cruel, uncaring murderer. The choices are endless. Like story structures, choosing an archetype merely gives you a place to start.

There are hundreds of different archetypes used in storytelling, though some are far more common than others and many can be combined into a single broader archetype, depending on your preferences. A full discussion of the many different archetypes and their variations and uses could easily fill an entire book of its own, so here I’ll just introduce you to ten of the more commonly used archetypes in video games. Keep in mind that although I refer to each of the following archetypes as either he or she, they can all be applied to characters of either gender.

The Young Hero

The archetypical young hero is often between twelve and twenty-five years old and is eager to go out and prove his worth by having adventures, succeeding in business, successfully performing a difficult task, or something similar. He tends to be cheerful, enthusiastic, and optimistic, and is often eager to help those in need.

Examples include Tidus (FINAL FANTASY X), Sora (KINGDOM HEARTS), and Guybrush (The Secret of Monkey Island).

The Reluctant Hero

In many ways the opposite of the young hero, he never had any interest in the task or adventure at hand. Forced into it by circumstances beyond his control, his only goal is to find a way out of it or, failing at that, to get it over and done with as soon as possible. On that note, he often tries to avoid helping others or engaging in anything that will add to his workload unless it greatly benefits him. Though initially not the most likable guy, he often matures and changes his attitude over the course of his journey.

Example include Kain (Blood Omen), Neku (THE WORLD ENDS WITH YOU), and Laharl (Disgaea).

The Best Friend

The hero’s best friend or sibling, she never leaves the hero’s side. Sometimes enthusiastic, sometimes reluctant, she provides a balance for the hero, either pushing him to action or urging him to slow down and carefully consider his actions. If the best friend and hero are not related and of opposite genders, they often grow to love each other.

Examples include Max (Sam & Max: The Devil’s Playhouse), Lucca (CHRONO TRIGGER), and Ryogo (FRONT MISSION 3).

The Special Person

Sometimes a hero, sometimes a villain, sometimes neither, she tends to be fairly young (rarely older than the hero) and somewhat mysterious. Alone in the world, she possesses a special power or ability that others seek to exploit, forcing her to act cautiously and often live life on the run. Having had a difficult life, she either maintains a bright and cheerful personality, always certain that things will improve, or withdraws within herself, becoming aloof and difficult to approach.

Examples include Reith (Magna Carta), Aeris (FINAL FANTASY VII), and Luna (Lunar Silver Star Harmony).

The Mentor

Wiser and more experienced than the hero (and usually far older), he takes the hero under his wing in an attempt to teach him and prepare him for the things to come. Often a former hero himself, he hopes the new hero will be able to complete an important task that he cannot. Believing firmly in the hero, he is willing to sacrifice anything, even his life, to ensure the hero’s success.

Examples include: Angeal (CRISIS CORE – FINAL FANTASY VII), Auron (FINAL FANTASY X), and the Boss (Metal Gear Solid 3).

The Veteran

A battle-hardened warrior who has lived through many battles: tough and practical, he focuses on completing his mission and getting out alive. If he himself isn’t the hero, he’ll lend the hero his aid and experience, often acting as a pseudomentor. Because of his difficult and dangerous life, in which any day could be his last, he tends to be either gruff and solitary or laid back and eager to enjoy the time he has.

Examples include Snake (Metal Gear Solid), Shepard (Mass Effect), and Ziggy (Xenosaga).

The Gambler

For her, everything is a game, with life being the biggest and most high-stakes game of all. She takes on jobs for the thrill and challenge, siding with whatever person or persons strikes her as the most interesting. Skill is important, but in the end, it all comes down to chance – and Lady Luck hasn’t failed her yet. Depending on her mood, she may side with the hero, the villain, or neither, and occasionally switches alliances to ensure that she ends up on the winning side.

Examples include Mion (Higurashi), Setzer (FINAL FANTASY VI), and Joshua (THE WORLD ENDS WITH YOU).

The Seductress

Beautiful and confident, the seductress is also greedy and opportunistic, always ready to use her looks and charms to get what she wants. Fiercely jealous, she’s merciless toward anyone she considers a threat to her ambitions. Because she sees love and compassion as just parts of the act, their true meanings are often lost on her. Her façade is difficult to penetrate, but deep down hides the heart of either a cruel villain or an insecure girl who wants desperately to be loved – not for her looks, but for who she is.

Examples include Eva (Metal Gear Solid 3), Caster (Fate/Stay Night), and Echidna (THE BOUNCER).

The Hardened Criminal

At home in the city’s seedy underbelly, he can obtain any item and perform any job for the right price. He may enjoy his work, reveling in the challenge and wealth it brings; he may just need the money; or he may simply know of no other way to live. Sometimes beneath his gruff exterior lurks a heart of gold, but he could just as easily be a scheming opportunist, ready to turn on his companions the moment it suits him.

Examples include Kyle (Lunar Silver Star Harmony), Niko (Grand Theft Auto IV), and Jack (Mass Effect 2).

The Cold, Calculating Villain

Driven, intelligent, and utterly ruthless, he’s working toward a certain goal and won’t hesitate to destroy anything or anyone that gets in his way. His plans are often big and complex, requiring years of planning and preparation, but he doesn’t mind being patient as long as his ends are eventually achieved. Whether he seeks power, wealth, revenge, or some other prize, all that matters is success. He may not even see himself as a villain, but instead as a hero, working toward the greater good, and may even lament the many innocents sacrificed along the way. But to him, their deaths were necessary. In fact, they should be grateful that they were able to give their lives in pursuit of his vision.

Examples include Wilhelm (Xenosaga), Primarch Dysley (FINAL FANTASY XIII), and Liquid Ocelot (Metal Gear Solid IV).

Advantages of Using Archetypes

Basing your characters around an existing archetype helps you ensure that their thoughts, personalities, and actions remain consistent with what they’re supposed to be, which is an important part of making characters seem real and believable (as we’ll talk more about shortly). As with story structure, archetypes can also give you a good place to start if you’re unsure of how a specific character fits into the story. And, much as with clichés, players are familiar and comfortable with common character archetypes. If a character stays true to his or her archetypical role, players can quickly gain a sense of the character’s personality and goals without the need for lots of dialog or backstory.

That said, unlike clichés, archetypes are endlessly customizable and by no means have to fit perfectly within the cookie-cutter descriptions I’ve provided. Furthermore, characters don’t need to be locked into a single archetype throughout the entire story. In FINAL FANTASY XIII (which we’ll discuss in depth later), Hope starts out as an extremely reluctant hero, cursing his fate, refusing to fight, and following the rest of the heroes only because he has no other choice. But as the game progresses, he learns and grows, first becoming possessed by a desire to become stronger and extract revenge on the people he blames for his predicament, and eventually embracing his role and becoming one of the most positive and heroic members of the group. Mixing multiple archetypes like this can make for very deep and nuanced characters, which goes a long way toward turning an average story into an amazing story.

Disadvantages of Using Archetypes

Because common archetypes are familiar and often fairly easy to recognize, characters run a serious risk of becoming predictable and even cliché if they stick too closely to their base archetype. That doesn’t necessarily mean that they won’t still be good characters, but it can certainly reduce their overall appeal.

More practically, trying to shoehorn every character you create into a predefined archetype or flipping through a list of archetypes for ideas every time you create a character is not only time-consuming but very restrictive as well. Archetypes aren’t meant to be used as a checklist. Some stories may need all ten of the archetypes I listed; others could be fine with two or three or maybe even none at all. Although you may occasionally want to think about what archetypes your characters fit into to try and ensure that they act appropriately, even that can be problematic. Sure, it might seem strange when a cold, calculating villain acts in a way more befitting a hero, but depending on that villain’s personality, mindset, and backstory, it might be perfectly within her character to do so. A certain character in Heavy Rain, for example (see the Heavy Rain case study in Chapter 9), spends much of the game acting like a hero only to eventually be revealed as a cold, calculating villain. However, when taken in context with his past and personality, the complete archetype reversal is believable and makes sense.

Though every writer has his or her own way of doing things, unless you’re trying to appeal to a specific market segment that really likes a particular archetype, I usually find it best when designing characters to forget about archetypes and just think about the type of character you want to create. What do you want him to act like? Why does he act that way? How was he raised? What important events took place in his past and how did they affect him? What will he add to the story? It’s questions like these that you should be asking yourself – not “Which archetype haven’t I used yet?”

Using Archetypes

The choice of archetype needs to be done artfully. Campbell’s archetypes are organically related to his story type, which is a journey from darkness to enlightenment. In Campbell’s Journey, for the hero to successfully navigate his or her path, he or she needs a mentor who has gone there before. If you’re writing Othello, in which that journey is not navigated successfully but instead ends in the tragic death of Desdemona, what you need instead is a bigger role for the Trickster, who is Iago.

—Chris

| Developer: | Square Enix Co., Ltd. |

| Publisher: | Square Enix, Inc. |

| Writers: | Tetsuya Nomura, Kazushige Nojima |

| System: | Sony PlayStation 2 |

| Release Date: | March 28, 2006 (US) |

| Genre: | Action RPG |

FIGURE 4.4

Square Enix and Disney characters combine to battle the Heartless in KINGDOM HEARTS II. © Square Enix, Co., Ltd. All rights reserved.

The extremely unlikely pairing of Square, known for bestselling RPGs such as FINAL FANTASY and CHRONO TRIGGER, and Walt Disney caused a stir among fans when it was announced. At first, most were sure that nothing good could come from a collaboration between such seemingly mismatched companies, but they would soon realize just how wrong they were. The original KINGDOM HEARTS, an action-packed world-hopping adventure featuring a wide range of characters from both Disney movies and FINAL FANTASY games, won over fans of both and went on to win critical acclaim and commercial success, launching one of Square’s most popular series. KINGDOM HEARTS II is actually the third game in the series, being released after KINGDOM HEARTS: CHAIN OF MEMORIES (a side story meant to fill in the gap between the end of KINGDOM HEARTS and the start of KINGDOM HEARTS II), but was the true successor to the first game, taking the original formula and gameplay and improving on them in every way.

The story of KINGDOM HEARTS follows Sora, a young boy who awakens one night to find his best friends missing and his home overrun by shadowy beings called Heartless. Unable to stop the destruction of his world, even with the help of the mysterious Keyblade, Sora finds himself in strange town, where he meets Donald Duck and Goofy. As it turns out, Sora’s world was only one of many (most of which are based on various Disney movies) and all are under threat from the Heartless. As the Keyblade wielder, he joins Donald and Goofy in their search for King Mickey in order to find his friends and stop the Heartless. KINGDOM HEARTS II picks up around a year after the first game (and a bit less time after KINGDOM HEARTS: CHAIN OF MEMORIES) as Sora and his friends find themselves facing a new threat in the form of the Nobodies and the deadly Organization XIII.

FIGURE 4.5

A number of famous Disney characters make appearances throughout the game. © Square Enix, Co., Ltd. All rights reserved.

With most of their movies based around fairy tales and other classic stories, Disney has a long history of creating their characters around common archetypes such as the princess, the hero, and the cold, calculating villain. When looking over their large collection of films, you’ll quickly notice that it’s rare for Disney’s characters to deviate too far from their standard archetype. However, the fact that their characters still retain their charm and popularity after so many years is a testament to the strength and creativity that goes into them. Even though they generally behave in predictable ways that are fully appropriate for their archetype, Disney characters have very well-established and entertaining personalities, be it Ariel’s driving curiosity or Aladdin’s wit and confidence. They also exhibit strong, believable emotions and react to situations in ways that perfectly fit their personalities. Just because they’re characters in a children’s cartoon doesn’t prevent them from showing love, anger, and even despair as the situation warrants it. Standard archetypes or not, Disney characters are all surprisingly human (even the nonhuman ones).

KINGDOM HEARTS II follows this trend, not only by accurately portraying the Disney characters, but by imbuing the series’ cast of original characters with the same style and charm. Cheerful, adventurous, and always eager to push forward, Sora easily fits the standard hero archetype, but even he becomes overcome with loneliness and depression at times when worrying about the unknown fate of his friends.

FIGURE 4.6

Despite following the standard hero archetype, Sora is a strong and believable character. © Square Enix, Co., Ltd. All rights reserved.

Xemnas, KINGDOM HEARTS II’s main villain, is a similarly interesting character. Despite being a perfect example of the cold, calculating villain with a complex master plan, careful manipulation of those around him, and a focus on his ultimate goal over all else, he still comes across as a deep and even pitiable character when his true purpose is revealed.

Although I do think that archetypes should be at most a secondary consideration when creating characters, if you want to see the many different ways in which even the most common and clichéd archetypes can be used to create an endless variety of interesting and entertaining characters, look no further than KINGDOM HEARTS II.

Creating cool designs and interesting backstories and personalities for your characters is all very important. But no matter how good a character is, if he or she acts in an unrealistic way players will have trouble connecting with and growing attached to the character. Of course, video game characters do unrealistic things all the time, like hurling fireballs, jumping twenty feet into the air, and destroying armies of demons with nothing but a sword. But when I say “realistic,” I’m not talking about the characters’ special powers or superhuman strength and agility – I’m talking about how they speak and the ways they act and react to various situations. After all, in other worlds things like magic, superhuman powers, and demon armies could all be perfectly normal parts of everyday life, but human behavior doesn’t change much with time or place. Although there’s plenty of variation to be found based on the specific character’s beliefs and personality, once you know a bit about someone, it should be fairly easy to predict how he or she will speak and react in different situations (barring a few extremely unpredictable situations and character types). When your characters don’t react in those predictable ways, then you might have a problem.

Grand Argument Theory

One way in which theater plays (dramas, mainly) have been described is as a Grand Argument. That is, the entire play is written in order to examine a particular point of view. Example: A Midsummer Night’s Dream discusses at length the nature of love. It uses multiple characters and situations, all designed to look at different points of view regarding love. These types of stories don’t use the Hero’s Journey, but instead have characters created to articulate different attitudes and points of view about the topic. Only at the end of the story do we discover what the author’s point of view about the topic might be, and this is done as the resolution of the story is revealed.

In those structures in particular, characters are created to function as diametrically opposed points on the circle so the arguments can evolve out of the drama.

The Hero’s Journey doesn’t work for every type of story.

—Chris

Character Actions and Decisions

The decisions characters make and the ways in which they react to different situations say a lot about them. Though simple decisions such as deciding whether to go out for pizza may generate a quick off-the-cuff response, when facing a more serious choice, many factors come into play. In the PlayStation 3 hit Heavy Rain, one of the characters is Ethan Mars, a father on a desperate and dangerous mission to find his kidnapped son Shaun before it’s too late. Forced to complete a series of challenges given him by Shaun’s kidnapper, Ethan is eventually tasked with murdering a certain man. Sensing danger, the man attacks Ethan with a shotgun, resulting in a tense chase sequence, but in the end, the man finds himself at Ethan’s mercy with a gun pointed at his head.

Heavy Rain leaves it up to the player to decide whether Ethan pulls the trigger, but let’s think about what would be going through Ethan’s mind at the time. Even though it might take only a few seconds to make the decision, there’s a lot going on behind the scenes. First and foremost, of course, is Ethan’s desire to save his son. If he fails the test set by the kidnapper, he has no idea whether he’ll have another chance or whether Shaun will be lost forever. In addition, the man is someone Ethan has never met before, admits to dealing drugs, and was gleefully chasing Ethan with a shotgun only moments before. Those can all be taken as good reasons to go ahead and shoot the guy. But there’s more at work. Although Heavy Rain doesn’t delve into Ethan’s religious and moral beliefs, he may have very strongly formed opinions about murder and whether it’s permissible. There are also repercussions to consider. If the police find out about the murder, Ethan could spend the rest of his life in jail. He may even be arrested before he gets a chance to save Shaun, rendering the murder and everything else he’s done worthless. And finally, on an emotional level, the man holds up a picture of his daughter and pleads with Ethan to let him go so that he can see her again, something Ethan can clearly relate to. Although Heavy Rain doesn’t bring up every issue I just mentioned, they’re all things that would be going through Ethan’s mind as he stands there with the gun. In the end, it’s a rather hard choice to make and it’s a credit to the writing and Ethan’s previous development that either decision fits very well with his character.

Other actions and decisions, however, are clearer cut. For example, earlier in Heavy Rain, before Shaun is kidnapped, Ethan is given a couple chances to spend some time with him. Depending on the player’s actions, Ethan could act as a concerned and loving parent or ignore Shaun entirely and do his own thing. However, if the player chooses to portray Ethan as a selfish, uncaring father, it won’t fit with the desperation and determination to save Shaun that he displays in later scenes, reducing his believability.

To give another example, though I won’t mention any names, I’ve seen far too many games in which the hero returns home to find his family murdered only to react in a rather emotionless and completely unbelievable manner. Usually something along the lines of, “Well, that’s too bad. Guess I’d better go avenge them now.” (Note that this is a general summation of the hero’s attitude and actions, not an actual quote.) Unless the hero really hated his family, their murder would be an extremely traumatic event. Sure, if he has a certain type of personality, he might seek revenge, but he’d also be an emotional wreck, most likely shifting between extreme cases of anger and despair. He may even find himself completely paralyzed by grief or contemplating suicide. Having him react in a calm and offhanded manner completely destroys the hero’s believability.

In a less extreme example, if your hero is portrayed as an honest, law-abiding person and is later given the option to rob a bank, he shouldn’t do it. Or, at the very least, it should be a very difficult thing for him to do. It makes no sense for an honest hero to commit a crime just because it’s convenient for the plot or the player feels like doing so. It would take a really serious situation (such as his girlfriend being held hostage) to make the hero do something that goes so clearly against his beliefs. Because of this, many games that give the player frequent choices between two or more opposing actions either offer strong incentives to encourage the player to stay firmly on a single path (therefore keeping the character’s actions fairly consistent) like in Mass Effect, or make the hero a generic blank slate so he or she has no predetermined beliefs, personality, or backstory, making consistency far less of an issue (though losing the chance to develop an interesting and memorable hero in the process).

Characters can change, but only gradually and over time. Similarly, they may occasionally make decisions that don’t fit the way they normally react, but only for specific reasons or if they’re under extreme duress. Any time a character, either as part of the predetermined story or due to player choice, performs an action that doesn’t fit his or her personality, the character loses a bit of believability, making it harder and harder for players to really identify with him or her.

Character Dialog

It’s also important to ensure that characters are consistent in the way they speak. People’s manner of speech can be affected by many things, including their personality, upbringing, social status, gender, and where they were raised. Even if they’re both speaking English, an orphan who grew up on the streets of New York and a Japanese businessman will have vastly different styles of speech. The orphan will probably talk in a fast and rough manner, with lots of contractions, slang, and broken grammar. By contrast, the Japanese businessman will likely speak slowly and politely in a very formal manner while avoiding slang and American expressions (which he may not fully understand).

If a character’s speech is too formal or too casual for his or her background and personality, the character is going to be less believable. Similarly, if a character uses terms, expressions, and idioms that he or she likely wouldn’t have learned, believability will suffer as well. For example, it would be strange for most Japanese people to use the expression “a penny saved is a penny earned,” both because it’s an American phrase and because Japan doesn’t have pennies. Naturally, a character in a fantasy world who says that would seem even more out of place.

Finally, when writing, be sure to remember that not every character is going to speak the exact same way you do. In fact, most of them probably won’t. That said, it can be a good idea to read your characters’ dialog out loud and think about how well it flows and how you’d phrase it if you were the one speaking. Doing so can help ensure that, if nothing else, your dialog at least flows naturally and doesn’t sound strange or stilted.

Case Study: FINAL FANTASY XIII

FIGURE 4.7

Lightning, Snow, and Vanille are all very different and believable characters. © Square Enix, Co., Ltd. All rights reserved.

Launched after a very lengthy development period, FINAL FANTASY XIII maintained the series’ history of top-quality graphics, music, and storytelling while continuing to experiment with different types of RPG gameplay. Some of these changes were better received than others. Though FINAL FANTASY XIII’s unique, fast-paced battle system was met with nearuniversal acclaim, Square Enix’s decision not to include the sprawling towns and complex mini-games that have been present in most past FINAL FANTASY titles (and, for that matter, most RPGs in general) was faced with very mixed reactions. Whether those were wise moves will likely be debated for years by fans, but we’re here to talk about FINAL FANTASY XIII’s story – and surprisingly enough, the lack of towns and limited exploration options actually served it quite well.

FINAL FANTASY XIII starts out in Cocoon, a planetoid of sorts floating high above the world of Pulse. For centuries, the two worlds have been at war, and even though it’s been hundreds of years since the last great battle, the people of Cocoon still maintain a deep fear of Pulse. In addition to humans, Cocoon and Pulse are also home to beings known as fal’Cie, who serve as rulers, protectors, and aides to the humans. If they desire, fal’Cie can also take human servants. Known as l’Cie, these humans are tasked with a single objective (called a Focus) and given great powers and magic in order to complete it. If they succeed, l’Cie are said to be rewarded with eternal life, but if they fail, they become Cie’th, mindless monsters who can do nothing but blindly destroy everything around them. Early in the game, five of the heroes – Lightning (a former member of Cocoon’s military), Sazh (a middle aged pilot), Hope (a young boy), Vanille (a cheerful, carefree girl), and Snow (a self-proclaimed hero and the fiancé of Lightning’s sister, Serah) – come into contact with a Pulse fal’Cie and are branded with the mark of l’Cie. Given a Focus they don’t understand, and on the run from virtually everyone in Cocoon (who consider the Pulse l’Cie to be a grave danger to their world, which is why the heroes can’t go strolling around towns and shops), this unlikely group struggles to find a way to escape their cursed fate.

FIGURE 4.8

The l’Cie mark grants great power but at a terrible price. © Square Enix, Co., Ltd. All rights reserved.

Though FINAL FANTASY XIII’s tale of Cocoon, Pulse, and fal’Cie is interesting enough on its own, what really sets the game apart is the characters. Lightning, Sazh, Hope, Vanille, Snow, and their later companion Fang make for some of the most emotionally complex and believable characters in gaming history. They all seem to start out as fairly predictable archetypes, but watching them grow and change over the course of the adventure is one of the highlights of the game. Lightning begins as a no-nonsense military type, unemotional and always focused on finding and destroying the enemy. However, as time goes on, you discover that her tough exterior is a façade created to help her deal with the challenges of working and raising her young sister after their parents’ death. Beneath her shell, she’s just as scared and confused as the others and isn’t sure whom or what she should be fighting.

Hope, who starts out doing nothing but blaming others and bemoaning his fate, eventually becomes obsessed with the desire to grow stronger and get revenge on Snow, whom he blames for the death of his mother, but slowly learns to take responsibility for his own actions and to stand up to protect the people who are important to him, becoming one of the most optimistic and committed members of the party.

Even the characters who start out seeming extremely one dimensional, like the perpetually cheerful Vanille and the confidently heroic Snow, turn out to be wrestling with many deep and troubling issues and are nowhere near as certain of their goals and actions as they want the others to believe. The major villains are very interesting as well. Some could easily be considered heroes in their own right, struggling to protect Cocoon against the l’Cie and other perceived threats – and even the true villain, who is willing to enact large-scale genocide to see his plans fulfilled, truly believes that what he’s doing is necessary to save the world from decay and destruction.

The way the heroes relate to each other and the world around them is also well done. Unlike most RPG heroes, who are perfectly willing to join together to fight evil the moment they meet, the cast members of FINAL FANTASY XIII start out with very different goals and motivations and spend much of the game trying to get away from both their fate as l’Cie and each other before events finally convince them to band together. They also have to deal with the fear and hatred of the citizens of Cocoon and the horrifying realization that, in order to save themselves, they may have to destroy the home they know and love.

Above all else, their problems, dilemmas, and uncertainty make the characters in FINAL FANTASY XIII feel extremely real and believable, making it easy for players to get drawn into the quest and share the characters’ confusion, sorrows, and triumphs. We hope that other game developers will look to FINAL FANTASY XIII, like they’ve looked to the series in the past, and use its example to create deep, complex, and believable characters of their own.

How Much to Tell and Not Tell Players

When you’re writing a story, there’s a lot more to it than just the events that take place in the game itself. Chances are good that your characters didn’t all magically spring into existence the moment the story starts. They have lives, histories, families, and years or decades of events and experiences that took place before the main story began. And then there’s the setting. Sure, a character might have a history spanning several decades or even a century or two, but the world in which your story takes place is probably far older, with a history stretching back thousands of years. Some of that information may be important to the main story and some might not, but it’s there ready for you to create, reference, and use whenever and however you please.

But how do you know how much of that information to use? Writing out the complete political history of your main characters’ homeland could be fun and would doubtless interest some players, but is it really the best way to be spending your time? Perhaps you should instead be writing detailed biographies for the important characters. Or maybe you should just ignore all of it and focus on nothing but the main plot. Deciding what information to spend your time creating, what to tell players, and how to tell them is yet another challenge you’ll face when writing for games.

Backstory or Not

Although this method may not work for everyone, Aaron Sorkin (The West Wing, Sports Night, A Few Good Men, Charlie Wilson’s War) is famous (or infamous, depending on your point of view) for not working on extensive backstory for his characters. He invents background about the characters on demand, as he needs it. When asked about this process, he stated that he’d rather keep his options open, that as he watched the actors grow into their roles, storylines would grow out of their performance and he didn’t want his hands tied.

One story that illustrates this method: early in The West Wing the president (Martin Sheen) and his wife (played by Stockard Channing) were in a scene at an official government ball, and they were to enter together down a staircase. This was their first scene they played together. At the top of the stairs, as they awaited their cue, Martin and Stockard began to compare notes about their characters. Martin had been in the pilot, but Stockard was cast only after the show had gone into production.

“How many children do we have?” Stockard asked.

“Well, the pilot mentioned one, so we have at least one,” replied Martin.

“You don’t know?” Stockard was surprised.

Martin laughed. “No, I actually have no idea.”

Stockard said “Well, I’ll ask Aaron.”

“Don’t bother,” Martin replied, “he doesn’t know either.”

When you look back on the series, and the crucial role that another Bartlett daughter came into play (indeed, not the one actually mentioned in the pilot), it is astonishing that Sorkin made this stuff up as he went along.

—Chris

Backstory, or the events that took place before your main story began, serves two main uses. First and foremost, it can help set up and expand upon the main story. Perhaps your hero has a strange aversion to fire. If that’s the case, at some point in the game you should probably spend a bit of time explaining the character’s backstory to show how he or she became that way. Similarly, if two countries in your world are at war because of an event that happened fifty years ago, you should consider having a story scene or in-game book that explains how the war began.

Of course, the more important these elements are to the main plot, the more vital it is that you explain them. If your hero’s fear of fire is a minor thing that’s only brought up once or twice, you might not need to bother explaining it. But if it plays a major role in the story, you can be certain that players are going to want an explanation. In some cases, backstory can play such a large role in current events that without it, the story really wouldn’t make much sense. For example, in Lunar Silver Star Harmony, many key plot points – including Ghaleon’s change from hero to villain and Luna’s true identity – are all related to the actions of the four heroes who saved the world long before the game began. If Lunar didn’t take time to explain the heroes’ quest and what became of them afterward, it would be very difficult (if not impossible) to fully understand the story.

Second, even if certain parts of the backstory have little to no bearing on the main plot, if your story is a good one, there are always going to be some fans who want more information about a particular character, place, or historic event just to satisfy their curiosity and learn more about the world and characters they’ve come to love. Adding in a lot of extra backstory elements will be sure to please those fans – though it should be noted that they’re usually in the minority, so the main plot should always be your primary focus and you should not force a whole lot of extra information on uninterested players.

Thanks to their interactive nature, games offer a myriad of ways to reveal backstory without having to worry about bogging people down with details or boring uninterested players. Elements that are very important to the main plot should be revealed throughout the game in conversations, cut-scenes, flashbacks, and the like, but there are many optional and subtler ways to convey the rest of your backstory.

The first is through in-game books (or scrolls, data discs, or similar means of transmission, depending on your setting). If the hero will be visiting various towns throughout the game, you can place libraries in one or more of them and fill the books with notes and trivia about the world and its history. Or, if the hero won’t have the chance to visit any libraries, he or she can get such books in treasure chests or from enemies. Backstory can also be revealed as part of optional side-quests or during conversations with various NPCs scattered throughout the world. Even important NPCs can give players the option to ask for more details about a particular person or event or just skip to the critical information.

If you want to make all the backstory and supplemental information very easily accessible to players, you can follow the current trend and place a database or log of some sort in the main menu. These databases generally contain anything from a brief summary to highly detailed information about the vast majority of characters, locations, and items in the game, among other things. Like libraries and optional conversations, they provide players with a wealth of extra information that they can choose to read or ignore. However, as all the information is contained in the menu, it makes it easy for players to read and reference it at their leisure at nearly any time during the game, which is far more convenient than hunting down books or NPCs. However, if you still want to give players some incentive to explore or at the very least want to avoid giving them too much information at the very start, you can set up the database so that certain entries become available only after the player has progressed far enough in the game or completed other specific requirements.

Earth and Beyond: The MMO

We worked in the backstory for Earth and Beyond in a method that illustrates one unique way to handle this issue. This was wholly the invention of our great lead writer, Angela Ferriaolo. Earth and Beyond was an MMO published by Electronic Arts in 2002 that told the story of humans originating from Earth as they colonized the solar system hundreds of years in the future. The game’s setup was that our part of space was invaded by aliens. But the puzzling thing for the players was that when the aliens first arrived, their ships would ply the human trade lanes and not do anything instead just flying back and forth. They didn’t attack, they didn’t communicate in any way the players could understand – nothing. Players didn’t know what to make of them. The alien ships would fly up to the player ships and broadcast a message, which appeared to be gibberish.

Separately from those ships, the players would be killing mobs (enemy groups). Some of those mobs would drop loot, called “fragments,” from their inventory. These fragments seemed to be inventory lists, pieces of some bigger document, but with no apparent worth. None of the NPCs in the game mentioned these fragments, so most players sold them as vendor trash. Then one player started to collect them (each fragment was numbered). The number of fragments exceeded the amount of space in any single players’ bank, so that player enlisted another in order to begin to collect all the different fragments.

Back to the aliens. One player began to play around, trying to translate the gibberish they were broadcasting. It turns out that they were speaking in a simple offset substitution cipher, and he began to translate the broadcasts. The aliens were broadcasting about two dozen different coded messages, so the players began to band together to assemble the translations.

As the different fragments were being assembled, players working on both sides of this mystery realized that the fragmentary messages were related to the alien messages, so websites sprung up within the player community outside the game to work on putting together the two sets of communications. Both the fragments and the alien messages were sending information about the ancient history of the galaxy, which in turn explained what the aliens were doing here. This all began to be unraveled as the story advanced with the next content push, at which time all the old messages were erased, along with all the old fragments, and both were replaced with new messages (with a new code) and additional fragments. At the same time, the aliens turned aggressive and the invasion began in earnest.

—Chris

As I mentioned earlier, in most stories there are at least some parts of the backstory that tie heavily into the main plot. As a general rule of thumb, if a certain piece of information is important to fully understanding the main story, be sure to include it. If information isn’t vital to the main story but explains a lot more about important characters, events, or locals, it’s good to include it (though perhaps in an optional form) and it should be fairly easy for players to find and access. Finally, if the information has little to no bearing on the story and is just there to further flesh out the setting, it’s nice to include in an optional form, but you shouldn’t put much time or effort into it until after you’ve finished creating the more important story elements.

As always, keep in mind that there are situations where these rules are best broken. In certain types of games – MMOs, for example – players often expect and want a large amount of backstory and supplemental material. In other games, some of which we’ll discuss shortly, it may be in your best interest to not reveal even certain parts of the main plot, no matter how important they are.

Case Study: FINAL FANTASY TACTICS: THE WAR OF THE LIONS

| Developer: | Square Enix Co., Ltd. |

| Publisher: | Square Enix, Inc. |

| Writer: | Yasumi Matsuna |

| System: | Sony PSP |

| Release Date: | October 9, 2007 (US) |

| Genre: | Tactical RPG |

Original Version: FINAL FANTASY TACTICS (PlayStation, 1998; PlayStation Network, 2009)

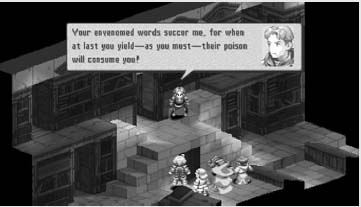

FIGURE 4.9

History has branded Ramza and Agrais as heretics, but their true story is long forgotten. © Square Enix, Co., Ltd. All rights reserved.

In addition to the main numbered entries, the FINAL FANTASY series has seen numerous spin-off titles. While some are direct sequels or prequels to other FINAL FANTASY games, most focus on new worlds and stories of their own. One of the most popular spin-offs, FINAL FANTASY TACTICS, was originally released on the PlayStation (and later rereleased as a downloadable title on the PlayStation Network) where it became a cult classic and went on to inspire a spin-off series of its own (FINAL FANTASY TACTICS ADVANCE). FINAL FANTASY TACTICS: THE WAR OF THE LIONS is a greatly improved PSP port of the original FINAL FANTASY TACTICS that contains new cut-scenes, quests, and game and multiplayer elements, along with an entirely new and vastly superior translation. What sets FINAL FANTASY TACTICS apart from the main FINAL FANTASY series is its battle system. Best thought of as a combination of a real-time-strategy game and a traditional FINAL FANTASY game, battles play out on large grid-based maps and focus heavily on careful strategy and planning in order to succeed. In this game, unlike most normal RPGs, players need to consider terrain, movement and attack ranges, charge time for spells and special attacks, and various other factors in order to be victorious. FINAL FANTASY TACTICS also features excellent character and party development in the form of a deep and highly customizable job system. Even now, more than ten years since its original release, FINAL FANTASY TACTICS is still considered by many tactical RPG fans to feature some of the best gameplay and character development in the entire genre.

Aside from its excellent gameplay, FINAL FANTASY TACTICS is also known for its deep and complex story. The opening starts out with Arazlam Durai, a historian in the country of Ivalice, who is seeking to discover the truth about the War of the Lions, which took place several hundred years before. Though history is quite clear on the events of the war, its heroes, and its villains, there are certain forbidden writings that paint the war and its key players in a much different light. Using his texts, Durai attempts to reconstruct the actual events, and it’s within this flashback or re-creation that the majority of the game takes place. The tale is long and complex, focusing on Ramza Beoulve, a young man condemned as a heretic whom Durai believes may have actually been the true hero of the war. The entire story covers several years of time, from the events leading up to the war to its sudden and shocking conclusion, and contains numerous important characters and locations.

FIGURE 4.10

A complex political tale weaves its way throughout the game. © Square Enix, Co., Ltd. All rights reserved.

Between the sheer complexity of the plot and Durai’s role as a historian, there’s a large amount of backstory and other information available, which is presented in several different ways. The first is optional conversations. Though FINAL FANTASY TACTICS doesn’t provide fully explorable towns, each town features a tavern where the player can, among other things, choose to listen to the current batch of rumors. Aside from providing information about occasional side-quests, these rumors contain information on local events and history and help explain how the common people are reacting to the war and other important events taking place around them. The player is also given access to an extensive database containing detailed biographies of every character in the game and summaries of important events, all written by Durai. As the story progresses, these writings are updated to reflect the latest information available, providing both a convenient reference and a large amount of supplemental material to better explain the characters’ histories, motivations, and roles in the war. Throughout the game, Ramza can also dispatch his party members on various optional quests, some of which result in the discovery of ancient ruins or treasures. These items are given their own database entries as well and serve to further explore Ivalice’s rich history while also referencing past FINAL FANTASY games. Finally, the player is able to obtain several books about the lives of various key figures in Ivalice’s past. Reading these books allows the player to play visual novel games to learn more about these ancient heroes (for an explanation of visual novel games, see Chapter 9). Unfortunately, for unknown reasons, the visual novels were removed from all English releases of FINAL FANTASY TACTICS, leaving only one of the books readable. Nevertheless, they were a very unique and clever way to explore Ivalice’s history.

Despite the disappointing removal of the visual novels in its English releases, FINAL FANTASY TACTICS provides an excellent example of the many different ways in which backstory and other noncritical information can be conveyed to the player in interesting and unobtrusive ways. The extreme popularity of the world of Ivalice, which led it to be used as the setting in several later Square Enix games, also goes to show how delving into the history of your worlds and characters can help them come alive and excite players.

Explaining most of the key story elements in your game is usually the best way to go, but at times you can create a much greater impact and more memorable experience by leaving out a few critical pieces and letting players form their own conclusions. However, leaving out important information while still keeping players happy is a difficult task. First, you need to include enough of the story that players have some idea of what’s going on and can form a reasonable guess as to the rest. That guess doesn’t have to be correct, and it’s perfectly fine if several different players come to several different conclusions, but making sure they have enough information to work with is vital. Without it, they’ll likely feel cheated or suppose that you don’t know the answers either and were just making things up as you went along. Second, you must ensure that despite any lingering mysteries, the ending still provides the player with a sense of accomplishment and closure. Without those two elements, the story will seem decidedly incomplete and will leave players discontented. Finally, you need to learn which parts of the story are okay to leave hidden and which aren’t. Though different people have different opinions on this matter, if you look at enough stories, you’ll discover that there are some things you simply can’t leave out without angering a large portion of players. For example, you wouldn’t want to end a murder mystery without revealing the identity of the killer. However, you could consider leaving the killer’s motives or methods a mystery and letting the player piece together the solution.

Unfortunately, deciding what to explain and what to leave out is a very complex subject, so I can’t simply give you a list of acceptable mysteries and leave it at that. You should also realize that anything you don’t explain in the story is bound to annoy and possibly anger some players. It’s really impossible to please everyone. However, if you examine other stories featuring mysterious elements and put a lot of thought into your story structure and what should and shouldn’t be left out, you may be able to craft a tale that will keep fans guessing and theorizing for months or even years after its release.

Case Study: Shadow of the Colossus

| Developer: | Team Ico |

| Publisher: | Sony Computer Entertainment |

| Writer: | Fumito Ueda |

| System: | Sony PlayStation 2 |

| Release Date: | August 6, 2008 (US) |

| Genre: | Platformer / Puzzle |

Shadow of the Colossus is the second title from Team Ico, the creators of the PlayStation 2 cult classic Ico. Despite their short track record, Team Ico’s games have become well known for their hauntingly beautiful worlds, rousing musical scores, brilliant puzzles, and subtle yet deep storytelling.

In Shadow of the Colossus, players take on the role of an unnamed young man who is often referred to as Wanderer. The game opens with Wanderer traveling to a lost valley, where an ancient temple sits. Entering the temple, he lays the body of a girl on the alter and begs Dormin (a mysterious supernatural entity) to bring her back to life. It is for this purpose that he broke the laws of his people and traveled to the forbidden land. Dormin agrees, but only if Wanderer can find and slay the sixteen colossi that roam the land. Wanderer’s quest is a mostly solitary affair and focuses entirely on exploring the world and finding and then defeating the colossi. There are no battles or puzzles on the way, putting the primary focus entirely on the colossi battles. The beasts themselves are unique and enormous – many towering several stories into the sky, making Wanderer seem like a mouse or ant in comparison. Finding ways to scale and kill such enormous and powerful creatures provides for what many consider to be some of the best boss battles in the history of video games.

The story is subtle, yet well told. Aside from the opening, ending, and a few brief scenes in between, things are rarely clearly stated. Instead, it’s left to the player to see the worry in Wanderer’s eyes as he looks at the girl and to watch as his body grows darker and more corrupted as each successive colossus is slain. Without even asking the question, it also forces the players to wonder if what they’re doing is really right. The colossi each have their own grace and personality and many seem to be perfectly gentle giants, not even trying to fight back until Wanderer plunges his sword into their bodies. We are told that land itself and Wanderer’s attempts to revive the dead are forbidden, and that he is being pursued because of it, but Wanderer’s relationship with the girl and the reasons for her death are shrouded in mystery. The months after Shadow of the Colossus’s release were filled with talk and speculation among fans about these very questions. Many thought the girl to be Wanderer’s sister or lover; others surmised that she was someone he had unjustly killed and the entire quest was an effort to atone for his sins. Dormin’s origins and intentions and even the ending itself are also vague and mysterious, leaving many unanswered questions and unsolved mysteries.

However, despite the lack of backstory and context, the story of Wanderer’s quest and ultimate fate is fully told. Even though questions were left unanswered, the ending does reveal the ultimate outcome of Wanderer’s actions and the consequences for him, Dormin, and the girl. In this way, it completes the story arc that began when Wanderer laid her body on the altar and provides the sense of closure necessary to keep players satisfied, while still leaving enough mysteries to keep them talking and thinking about the story longer after they’ve seen the credits roll.

Case Study: Braid

| Developer: | Number None, Inc. |

| Publisher: | Number None, Inc. |

| Writer: | Jonathan Blow |

| System: | Microsoft Xbox 360, Sony PlayStation 3, PC |

| Release Date: | October 18, 2005 (US) |

| Genre: | Action Adventure |

FIGURE 4.11

A deceptively simple journey.