CHAPTER

Eleven

Fully Player-Driven Stories

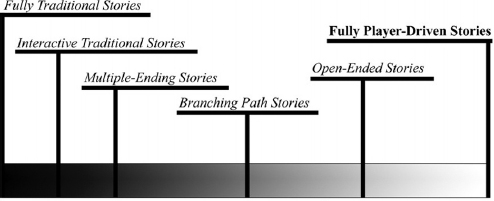

FIGURE 11.1

Fully player-driven storytelling.

At last we’ve reached the far right end of the spectrum and the most player-driven form of storytelling possible. When compared to all the other storytelling styles we’ve discussed, fully player-driven stories are a bit of an oddity. All the other storytelling styles were defined by the amount of control, or lack thereof, that the player has over the progression and outcome of the main plot. That control can be anywhere from entirely nonexistent to relatively high, but either way, the main plot is still there to guide players through the game and tell some sort of story. As vital as the main plot is, it also restricts player control and freedom, forcing players to at least somewhat follow a set path through the game. That’s why fully player-driven stories don’t have any main plot at all.

Now you’re probably wondering how you can have a story without a main plot. And, to some extent, you can’t. However, instead of using a main plot created by a writer and/or designer, the main plot in fully player-driven stories, such as it is, is composed of the player’s actions within a given setting. As such, some fully player-driven stories, such as The Sims, have little need for writers. Others, however, like Animal Crossing rely on writers to create the world, characters, and general setting with which the player can interact. What the player does in that setting may be entirely up to him or her, but the writer still needs to give that setting and its inhabitants names, backstories, personalities, and the like.

A Story by a Committee Is a …

I fall into the camp of those who believe that fully player-driven stories do not define themselves as stories per se. Though I earlier stated that story is change due to conflict, I also subscribe to the philosophy that story exists in the gap between expectation and result. Here’s what I mean by that.

At every single moment in a story, the audience is expecting something to happen next. In their heads, they are predicting where the story will go a millisecond before it gets there. They have assembled in their head everything they know about the characters, everything they know about the setting, everything they know about human nature, and everything they know about the plot. And they have computed what will happen next on every level of the story, from what Indiana Jones will say next to whether he will be able to prevent the Ark from being loaded on that German submarine to whether he and Marion will get back together. And, in a fascinating twist of human psychology, the audience wants to be both right and wrong about their predictions.

The audience wishes to be right so they can show off how smart they are to both themselves and their friends. Because, you see, being smart about stories translates to wisdom about life in general as well as demonstrates a creative bent.

The audience wishes to be wrong because they love being surprised by stories. In fact, being surprised by stories is perhaps the most singularly delicious aspect of story enjoyment. To not see something coming in a story means that the writers have done their job, been clever, been creative in the extreme, and, most importantly, been entertaining. If you don’t believe this, just think back to the heady days just after The Sixth Sense was released in theaters and try to remember how moviegoers were imploring you to go see it but emphatically refused to tell you how it would end so that they didn’t spoil it for you. Surprise is the Super Bowl Championship of storytelling.

In order to surprise an audience, you must stay ahead of them. Successfully having laid down a perfectly plausible future path for the characters and then having changed direction enough to surprise the audience – a combination of being organic and artful – comes from the structural foundation the writer has laid in all the beats and scenes leading up to this moment in the story, and does not happen by accident or randomness, but instead by careful planning.

The writer has set up an expectation in the audience but delivered a different result. This is crucial to entertaining writing, and it is why I enjoy stories. How this can occur in a fully player-driven story I cannot fathom, as the creator and the audience are one and the same. Although I can certainly enjoy playing by myself, and I can make up little scenarios in my head during that experience, those episodes of make-believe, though entertaining, are not as enjoyable for me as audience member as stories I consume written by someone else.

—Chris

Case Study: The Sims

| Developer: | Maxis |

| Publisher: | Electronic Arts |

| Designers: | Will Wright, Claire Curtain, Roxy Wolosenko |

| System: | PC |

| Release Date: | February 4, 2000 (US) |

| Genre: | Simulation |

FIGURE 11.2

The Sims lets you create entire families with their own personalities and interests. The Sims images © 2010 Electronic Arts Inc. All rights reserved. Used with permission.

In the world of computer game designers, there are few names more famous than Will Wright. This legendary game designer was the driving force behind much of Maxis’s popular Sim line of games including classics such SimCity, SimEarth, SimCopter, and SimAnt, along with his more recent hit, Spore. Wright’s early simulation games mostly focused on the big picture by having players create and manage an entire city, planet, ant colony, or the like; The Sims brought the focus narrower and closer to home. Instead of controlling an entire group or complex, it challenged players to create and manage the life of a single human being, or Sim. Despite many describing it as more of a toy or virtual dollhouse than a true game, The Sims became a huge hit and unseated Myst to gain the title of bestselling computer game of all time (for a while, anyway).

Since then, The Sims has received numerous expansion packs, sequels, and spin-off games. Some versions have changed the formula a bit, even going so far as to work in a main plot of sorts, but the original game has no story, no set goals, and no victory condition. Players are free to set goals of their own, such as getting their Sim a good job, starting a family, or just saving up enough money to buy a hot tub; however, these goals exist only in the mind of the player and aren’t recognized or acknowledged in any way by the game itself.

FIGURE 11.3

As in real life, socialization is an important part of any Sim’s life. The Sims images © 2010 Electronic Arts Inc. All rights reserved. Used with permission.

Players start out by creating a Sim and building a house for that Sim. The building tools are very comprehensive and there’s an enormous number of materials and items available for players to build their ideal home. Although some of these are far too expensive for new Sims to afford, players can work toward buying them later on. Once the initial creation process is complete, the Sim is ready to go about his or her daily life. Sims go off to work (or school, depending on their age) every day, but the game focuses exclusively on their home life. Although Sims have enough AI to go about some tasks by themselves, it’s up to the player to control most of his or her Sim’s actions and ensure that the Sim eats well, exercises, maintains proper hygiene, and so on. Properly managing a Sim’s social life is also an important part of ensuring that the Sim remains happy and content. Players can invite other Sims (either ones they created or a collection of premade ones) to their Sim’s house for parties and other social gatherings – it’s even possible for two Sims to get married and have children.

There’s no real plot, no dialog (Sims converse in a made-up language known as Simlish), and very little writing at all. Instead, The Sims is all about giving players near complete control so that their actions can tell the life stories of their Sims. Many people would probably argue that The Sims doesn’t have a story of any kind, and in some ways that would be correct. However, the large amount of fan fiction, comics, and movies that players have made chronicling the lives of their Sims shows that there is a story to be found, if only in the minds of the players. Nevertheless, The Sims expertly embodies the key principles of fully player-driven storytelling: specifically, creating an engaging setting and rules of interaction to govern activities within that setting and then letting players loose to do as they please and create their own stories.

Toy or Game?

Although this might seem simply a semantic argument, The Sims to me – while amazingly engaging to millions of consumers – is a toy, not a game. A beautifully conceived and implemented toy, but a toy nonetheless. Nothing wrong with a toy: toys can be and are the most amazing things to play with, and the persons who play with toys will always conceive of stories to accompany their playtime. And as long as game designers supply the proper context for the play, the best stories to come out of those experiences will be those created by the players.

—Chris

Creating Fully Player-Driven Stories

Because of the lack of a main plot, the creation process for fully player-driven stories is a bit different from that of the other styles we’ve talked about. You can pretty much forget about structure, pacing, endings, branching paths, and the like. Things like backstory and character types, however, can still be useful. In the end, when you don’t have a main plot, your only real concerns are creating a setting and the rules governing how players interact with that setting.

In interactive traditional, multiple-ending, and branching path stories, the setting – no matter how unique and interesting it may be – tends to take a back seat to the main characters and their journey. If you think about the stories in games such as the Metal Gear and FINAL FANTASY series, you’ll see that in most cases you could take the characters and place them in a different city/country/world without having to make many serious changes to the main plot. Sure, things would be a bit different, but the majority of the story is tied up in the characters, not the specific setting, and would remain unaffected. Even in open-ended stories, in which the setting plays a much more important role, the main plot is still there.

In fully player-driven stories, however, you need to avoid thinking of the setting as the backdrop for your story and instead approach it as a fully realized world that players can enjoy exploring and interacting with. The settings used in some open-ended story games such as Fallout 3 and The Elder Scrolls 3: Morrowind are actually large and detailed enough that they could easily become fully player-driven stories if the main plot were removed, so all the setting-related advice from the previous chapter still applies. Whether your setting is an entire planet or just a single town, you want it to be interesting and fun to explore, with lots of things for the player to see and do. Also, keep in mind that most settings are nothing without the characters that inhabit them. Just because there’s no main plot doesn’t mean your fully player-driven story can’t be full of characters for the player to talk to, work for, befriend, fight, and the like. In fact, with no main plot, it’s the NPCs that serve to give a fully player-driven story much of its charm and personality.

Naturally, it’s also important that your setting supports a lot of different activities to keep the player entertained. Similar to the distractions found in open-ended stories, but even more important because there’s no main plot to back them up, these activities can include virtually anything – fighting, fishing, treasure hunting, socializing, or even short quests and mini-games. As long as it fits the setting and makes for a fun way to pass some time, go for it. If you’re both a writer and designer, you’ll probably be planning most of this out yourself. However, if you’re just a writer, you’ll most likely be limited to writing text and dialog for activities created by the designer.

With your setting planned out, the next thing to consider is what the player will be able to do in that setting. You may have already given this some thought when designing NPCs and planning out activities for the player to do, but in many cases at least half the fun in fully player-driven stories comes from the player messing around with the world and its inhabitants and finding his or her own forms of amusement. To facilitate this, you need to decide exactly what the player can and can’t do in the world. Note that this is really the designer’s role, not the writer’s, so depending on your exact position on the team, you may or may not have much to do with this phase. However, even if you’re not involved in planning the rules of interaction, you should study them and try to keep in mind exactly what the player can and can’t do so that you can tailor your writing accordingly.

Actions Speak Louder than Words

The best example of actions speaking louder than words that I can think of is the MMO game Eve. Eve is truly the poster child of this design/writing philosophy.

The single most powerful choice a writer of a game-story makes is this: “What is the player going to do from minute to minute during play?” because in a game, the player is making the decisions, and decisions (and their repercussions) lead to an emotional response – a response potentially far more powerful than an empathic one traditional media delivers. This is why we want to write for games, no? We do it in order to deliver a more compelling experience. Well, at the risk of acting as a sort of wake-up call: in an interactive medium, words don’t cut it so much. They can be cool, and they can deliver in games some of what they could deliver in novels, but they are weak sauce compared to things the player does. So if you intend to have a lasting effect on the games you write for, try to get in the design room as early in the development process as possible so that you can suggest game activities for the player. And by this I mean literally everything, from whether the player can jump to what kinds of attacks the player has in addition to the standard writerly-things such as what kinds of missions the player can go on. Now, the game designers aren’t going to give up this kind of responsibility so easily, mind you, but you know that your input here – with all of your instincts and knowledge and experience in the areas of creating emotion in your audience – creates impact through these decisions instead of, well, writing words that many players aren’t going to read anyway.

Eve’s decision to let the players operate their spaceships inside a PvP (that is, player-versus-player) world is not only a bold decision story-wise, but a great decision, given the size of their development team and their development history. It allowed them to not have to worry so much about content creation at a time when they might not have had the capacity to deliver that content. But the best part of their decision was this: they built the conflict into their world design, and allowed the world to change due to the players’ actions. “Change through conflict.” From an MMO perspective, this was possible only because they set their universe on one server, so that the player actions were contained within that single place and had the ability to affect the entire player base at once. Brilliant choice.

—Chris

Depending on the type of game you’re trying to create, the rules of interaction can be fairly simple or extremely complex. In many fully player-driven stories, such as the ones we discuss in this chapter, they tend toward the latter. For example, say that the hero approaches a door. The rules of interaction may say that he can knock on the door or open the door, as long as it isn’t locked (or they might say that he can’t interact with the door in any way – it all depends). But that’s just the beginning. In real life, the hero could try to break down the door with his own strength, bash through it with a rock or axe, attempt to pick the lock, burn the door down, melt through it with acid, or choose any of a number of other possible options. Now let’s get back to that in-game door. Do you want the player to be able to pick the lock, bash down the door, or burn through it? If so, you need to plan for those possibilities and include them in the list of ways the hero can interact with doors. For another example, when the hero approaches an NPC, you need to decide whether the hero has the ability to talk with her (and if so, what types of things he can say), attack her, kill her, bribe her, serenade her, and the like.

For any given situation, there’s a nearly infinite list of possible interactions, so it’s important to narrow them down to a more reasonable number. Naturally, interactions should be appropriate for the setting and hero (if the hero is an elephant, flying probably isn’t an appropriate interaction). They should also encompass the things that players will most likely want to do. For example, most players will probably want the ability to talk to NPCs, but they might not care whether they have the option to challenge every NPC to a game of leapfrog. Most importantly, every type of interaction you decide to allow will need to be designed, programmed into the game, animated, and so on. As you’ve probably guessed, all of this takes time, effort, and money. If you try to add in too many possible interactions, you’ll soon find yourself overwhelmed. Bug testing can also become a huge problem when players decide to try using the different interactions in unexpected ways (such as serenading a door or unlocking an NPC). There’s a reason why many highly complex fully player-driven story games take so long to develop.

The Problem with Fully Player-Driven Stories in Video Games

As we just discussed, at any point in time there is a practically infinite number of possible actions that any person can take. Right at this very moment, you could keep reading this book, take a break to make a sandwich, get up and go to the movies, read the rest of the chapter while standing on your head, or dance the hokey pokey while singing show tunes – and that’s barely scratching the surface. I could write an entire book listing the many different things you could do right this minute and still not mention them all. Of course, many of these potential actions are highly unlikely to take place. Reading while standing on your head isn’t very comfortable or practical and you may not know the hokey pokey or like show tunes. And, even if you do, you may be too embarrassed to sing them or just think that the whole idea is too stupid to entertain. But that doesn’t mean you can’t do it. Even if the odds of you deciding to are very low, it’s still possible. If you’re wondering where this is going, think back to how every potential player interaction you add to a game takes additional time, effort, and money. Now, when combined with the fact that the potential types of interactions that could be added are infinite, or nearly so, you should see the problem. No matter how many options and interactions you add to a game, how many conversation topics and lines of dialog you write, and how many areas you create, there will always be things that the player can’t do or say and places he or she can’t go. Sure, most players probably won’t care about many of the things that get “left out,” but somewhere there’s going to be a player who’s disappointed that there’s no hokey pokey show tune option.

And that brings us to the inherent flaw in video games using fully player-driven stories. No matter how much time, effort, and money are poured into a game, it’s impossible for the player to ever have the amount of freedom and choice that’s present in any real-life situation. Simply put, creating a perfect fully player-driven story in video games can’t be done. That doesn’t mean you can’t make an enjoyable game that allows the player a large degree of freedom. You can. You just need to realize the limitations both of the medium and your development team.

In the end, a perfect fully player-driven story is possible only if you have a real live person acting as a moderator. To get an idea of how that works, let’s take a look at a game that uses perfect fully player-driven storytelling.

Case Study: Dungeons & Dragons

| Original Designers: | Gary Gygax and Dave Arneson |

| Publisher: | Wizards of the Coast |

| Release Date: | 1974 (Original), 2008 (4th Edition) |

Although far from the only tabletop role-playing game available, Dungeons & Dragons (D&D) is the most well known and is widely regarded as one of the primary influences behind not only tabletop RPGs but RPG video and computer games as well. Combining elements of fantasy novels, battle strategy, games of chance, storytelling, and even improvisational theater, D&D challenges players to create characters and take part in fully player-driven stories under the watchful eyes of a dungeon master, or DM.

D&D is composed of a series of books, including three core volumes (Player’s Handbook, Dungeon Master’s Guide, and Monster Manual) and a very wide assortment of supplementary works. These books contain a detailed description of a setting (including its world, races, religions, gods, wildlife, and the like) and all the relevant rules of interaction (how characters get stronger, perform tasks, fight, learn new skills and magic, and the like). Players use this information to create a character (such as a half-human, half-elf ranger who is smart and fast, but weak, and is able to converse with dragons) and learn how to play the game (which dice to roll when attacking and defending, how to craft a new bow), but it’s the job of the DM to truly learn and master the material contained in the books.

The DM serves as the game’s master, writer, and narrator. He or she creates a story, explains the setting to the players, and controls the enemies and NPCs. For example, when players enter a town, the DM might say something like, “You’re in a small village next to a forest. There are a few dozen wooden buildings including a general store on the left and a tavern to your right. Several people are milling about. An old woman in a tattered dress is walking toward you.” Although the DM usually creates a main plot for the players to follow, it’s up to the players to decide how to accomplish the goals set before them. And that’s assuming they decide to follow the plot in the first place, as they can easily ignore it and get sidetracked doing other things.

The advantage of having a human running things is that a good DM can quickly change the game and ensure that NPCs react properly, no matter what the players decide to do. Using our town example from the previous paragraph, it’s quite likely that the players will decide to see what the old woman wants, go to the store to restock their supplies, and/or stop by the tavern for drinks. Most DMs will have considered all those possibilities and planned for them. But there’s no guarantee that the players will do any of those things. Perhaps the players will decide that they want to go look for a weapon master for training, go on a murderous rampage, or start doing an impromptu acrobatic performance. It’s then the DM’s job to change the story and tell the players the results of their actions. With enough imagination, a DM can think up the results of any action the player could possibly take, adjust the story as needed, and keep things more or less on track, giving the player complete and total freedom to do and act as he or she pleases. It’s this freedom that sets D&D and other tabletop games apart and that has helped them maintain a loyal following despite the rise in popularity of video games and other forms of multimedia-rich interactive entertainment.

As you can see, a perfect player-driven story – even one with a main plot – is possible if you have a live person available to run things and modify the story on the fly. But is there any way to replicate this in a video game? At present, not really. Although it’s technically possible to have a human moderator filling a DM-like role in a video game, the need for one moderator per player (or player group) and for the moderator and player to be on at the same time makes it highly impractical for commercial games. In addition, unlike in D&D, where the players can go anywhere and do anything that they and the DM can think of, a player in a video game can’t go anywhere that wasn’t previously planned for and modeled and can’t do anything that the game’s programming doesn’t allow for.

There is one way that you could theoretically create a perfectly fully player-driven story in a video game without the need for a human moderator. In theory, a suitably advanced AI could take on the DM’s role. If the AI were smart enough to understand both the story and whatever actions the player could conceivably take, it could then fill in the gaps and modify things as needed, even creating new characters and areas on the fly. Of course, all of that is only theoretical. At this point in time, it’s often hard enough to make an AI that can guide an NPC from point A to point B without getting stuck on a tree in between. An AI with human or near-human levels of comprehension is purely the realm of science fiction. And even if such an AI did exist, it’s hard to say whether the stories it made would contain the same skill and creativity as those of a good human writer.

There’s considerable debate among AI programmers and future technology analysts as to how long it will take us to create such an AI. Although the most optimistic estimates place the date within the next decade or two, others question whether it will ever happen, citing the fundamental differences between the workings of computers and the human brain. I’m by no means an AI expert, but my own knowledge of the field and a look at the accuracy of other predictions by some of the more optimistic members of the debate have led me to believe that the creation of such an AI – if it’s even possible – is a very distant event (several decades at least, and probably much longer). If such a thing does happen, it will significantly change the role of the writer in video games, possibly even removing the need for one entirely, though getting replaced by an AI probably isn’t something we’ll have to worry about during our lifetimes.

Massively Multiplayer Online Games (MMOs)

MMOs have come a long way, developing from a small niche market into one of the industry’s most popular genres, though not one known for its storytelling (see Chapter 14). MMOs come in many forms; the most popular by far is the MMORPG (massively multiplayer online role-playing game), which encompasses hit titles including Ultima Online, Everquest, Guild Wars, and World of Warcraft. Although I suspect most of you are quite familiar with the genre, for anyone who isn’t, MMOs are games that are played online in virtual worlds inhabited by anywhere from thousands to millions of other players. Most MMOs feature a strong emphasis on player cooperation during the PvE (player-versus-environment) portions of the game, with large groups of skilled players required in order to defeat the toughest challenges. It’s also common for MMOs to include PvP (player-versus-player) elements, though whether players are free to attack each other in any area or only in designated PvP zones varies by game.

The story structures in MMOs vary but usually fall into one of two categories. The majority of MMOs use fully player-driven stories. They provide players with a large world to explore (often complete with a long and detailed history), along with lots and lots of enemies to kill, items to find, and quests to undertake. Some include numerous additional activities as well, such as crafting items, buying property, cooking, and the like. Although there’s usually no main plot, it’s common for MMOs to place players in the midst of a major conflict (though their role in the events is often extremely minor), and some contain chains of several quests that combine to form a short story with the player as one of its major characters.

Fully player-driven stories are the most common type used in MMOs, but there are also a few popular titles that use interactive traditional stories. Guild Wars is a good example of this style. Though it still contains a large world and wide variety of quests, there is also a set of missions (larger plot-related quests) that must be completed in order for the player to progress in the story and gain access to additional quests and other parts of the world. Once all the missions have been completed, however, the game changes into a fully player-driven story, leaving the player free to explore the world, complete quests, hunt for rare items, and so on.

Case Study: World of Warcraft

| Developer: | Blizzard Entertainment |

| Publisher: | Blizzard Entertainment |

| System: | PC |

| Release Date: | November 23, 2004 (US) |

| Genre: | MMORPG |

FIGURE 11.4

Traversing a frozen expanse in World of Warcraft’s Wrath of the Lich King expansion. World of Warcraft®, Wrath of the Lich King™, and The Burning Crusade™ are trademarks and/or registered trademarks of Blizzard Entertainment, Inc., and hereby used with permission. Image used with permission. © 2010 Blizzard Entertainment, Inc.

Although it’s far from the first MMORPG, World of Warcraft is the game that comes to mind when most people think of the genre. Shortly after its release, World of Warcraft took the industry by storm, dominating the market and rapidly become the most popular MMORPG available, a position it has successfully held ever since. Though it relies on many elements common throughout most MMORPGs, such as simple quests, item collection, crafting, and player guilds, World of Warcraft’s high level of polish, attention to detail, and frequent updates, along with its use of the setting from the popular Warcraft series of strategy games, have helped set it apart from other similar titles.

As with most MMORPGs, World of Warcraft uses fully player-driven storytelling. Upon starting the game, players build a custom character by choosing attributes such as race (orc, elf, human, and so on) and class (mage, warrior, druid, and so on) and decide whether to join the Horde or Alliance in their ongoing conflict. The character is then turned loose in the fantasy world of Azeroth. Many different quests and activities are available from the start and more open up as the player progresses and increases his character’s level. As in most MMORPGs (and regular RPGs, for that matter), the bulk of these optional quests tend to involve killing certain enemies, collecting a certain amount of a specific item (often gotten by killing enemies), or delivering something to an NPC in a different area. The dialog the player has with NPC quest givers and the additional information found in the player’s journal serves to add purpose and color to these tasks and also teaches the player about Azeroth’s people, history, and current situation. In addition, many quests come in sets, forming quest chains that allow the player to take on an important role in a short story. For example, the Wrath of the Lich King expansion contains lengthy quest chains following various characters’ efforts to find a way to defeat the evil Lich King Arthas. Although only a small part of World of Warcraft as a whole, the Lich King quests and certain other quest chains can actually be thought of as complete interactive traditional stories in their own right, with beginnings, progressions, and endings, complete with special characters, dialog, bosses, and cut-scenes. Though they make up only a portion of Azeroth’s lore, such quest chains do much to expand the setting and backstory while also providing a more story-focused experience for players who have little interest in farming monsters for experience points and rare items.

One important thing that sets MMOs such as World of Warcraft apart from single-player games is that the player is far from the only hero in the land. Therefore, no matter how many times he kills the Lich King, he’ll still miraculously return to challenge the next group of adventurers. Many quests can even be completed multiple times by the same player. Because of this, it becomes difficult to show any massive and/or world-changing events as a result of the player’s actions. With so many players exploring the same world, it can’t go changing every time someone completes a new quest. One solution to this problem involves the use of instances, which are unique copies of a portion of the world that are inhabited only by the player and his or her party. While in an instance, the results of the player’s actions can safely be shown without affecting any unrelated players. However, once the player leaves the instance and returns to the main shared world, any changes made while in the instance are lost. This system allows many players to experience the same story elements while still sharing a world but requires the writer to always keep in mind what exactly can and can’t be shown in the game in order for the story’s progression to remain smooth and consistent.

FIGURE 11.5

A meeting of elves in the Burning Crusade expansion. World of Warcraft®, Wrath of the Lich King™, and The Burning Crusade™ are trademarks and/or registered trademarks of Blizzard Entertainment, Inc., and hereby used with permission. Image used with permission. © 2010 Blizzard Entertainment, Inc.

Another aspect that should be kept in mind when looking at World of Warcraft is the difficulty of individual quests relative to the rest of their quest chain. Defeating the Lich King, for example, is far more difficult than many of the quests leading up to that battle. As in all video games, it’s only natural to have the difficultly gradually increase as the story progresses. The difference is that in single-player games things are fine-tuned so that the player can smoothly progress through the story from start to finish, yet a considerable amount of content in MMOs is targeted at players with specific levels or skills, or those in groups of a certain size. Although there’s nothing wrong with this, as it helps encourage players to join groups and try out new types of characters, it’s important to ensure that any player who successfully starts a quest chain has a reasonable chance of being able to finish it, instead of being forced to quit in the middle and missing out on the rest of the story. World of Warcraft does a pretty good job in this regard and presents many examples of strong flow and pacing throughout individual quest chains.

These are only a few of the challenges faced when creating an interesting and engaging setting that can accommodate a large number of players at once; though difficult, they can all be overcome with careful planning and design. A good MMO such as World of Warcraft makes sure to provide many interesting story elements and quest chains for players who prefer a more structured experience, but doesn’t force too many of those elements on players who just want to ignore the story, fight monsters, and power up their characters. Though many different MMORPGs have offered their own unique approaches to this issue, none can claim the player base or enduring popularity of World of Warcraft, making it the perfect example of how fully player-driven storytelling can be used to create an immense and satisfying online gaming experience.

WoW Changed Everything!

Storytelling in MMOs has the potential to be delivered very differently than we have seen in most state-of-the-art MMOs, at least those designed on the World of Warcraft model. World of Warcraft was a seminal product because it showed that players would embrace a play model in which leveling speed (the speed at which the player’s character gains levels and grows stronger) could be coupled with advancing through the storyline in an enjoyable manner. In short, that story could be consumed and enjoyed along with killing MOBs continuously over time, and players would like this change of pace. Remember, the only model we had seen before this was really EverQuest, which – contrary to its name – didn’t have very many quests.

Server design and build processes currently dictate that all content on all player servers be identical. Stated in a different manner, with today’s technology, you can destroy an enemy NPC on one server forever, while on another server, that enemy continues to live. You either get to kill these NPCs over and over again on each server, ad nauseam, or they are killed forever across all servers at the same time (that is, with a content update).

In that kind of environment, the way you can leverage story best is through factions, meaning, or having the players do quests to raise or lower their factional status with a certain political group in the universe to allow the players to gain access to quests, zones, treasure, and so on. In this way, identical content can serve both players without the status with that political group as well as those who have the status. Thus, the universe will change for those players yet stay the same for others.

—Chris

The Strengths of Fully Player-Driven Stories

Without a main plot or any sort of strict structure, fully player-driven stories offer the players far more freedom and control over their actions than any other type of storytelling. Within reason, the player is free to spend time doing whatever he or she wants, and can even create his or her own goals and story. There are few deeper or more comprehensive ways for players to explore a fictional world. Additionally, the large degree of freedom and experimentation – combined with all the optional quests and distractions usually found in fully player-driven stories – give them a near infinite amount of replay value, ensuring that players will always be able to find something to keep them occupied.

Case Study: Animal Crossing

| Developer: | Nintendo |

| Publisher: | Nintendo |

| Writer: | Kenshirou Ueda, Makoto Wada, Kunio Watanabe |

| System: | Nintendo GameCube |

| Release Date: | September 15, 2002 (US) |

| Genre: | Simulation |

Animal Crossing can be thought of as one of Nintendo’s early attempts to appeal to casual players and nongamers, though it gained quite a few hardcore fans as well and spawned sequels on the DS and the Wii. Despite having no plot and little backstory, its charming characters are a testament to Nintendo’s skilled writing and translation staff.

Animal Crossing begins when the player-created hero moves into a small town and takes out a mortgage from the local store to buy his or her first house. Much like The Sims, there’s no real story beyond this setup – and no set goals, either. The player can work to pay off his debt to Tom Nook, the raccoon storekeeper, which leads to his taking on another larger debt in order to expand his house (a cycle that can be repeated several times until the house is fully upgraded), but even this is optional, as there are no deadlines or penalties for not doing so. Instead, the player is free to spend his days exploring the village and taking part in numerous relaxing activities such as fishing, searching for fruit, gardening, bug catching, digging for fossils, and shopping for new furniture and other items to improve his house (which is periodically rated on its overall design), just to name a few of the many different pastimes. There’s even a set of old NES games (including classics such as Super Mario Brothers and The Legend of Zelda) that can be collected and played. Players can also devote time to improving the village itself by pulling weeds, picking up trash, planting trees and flowers, and the like, which can in turn attract more residents to move in.

It’s these residents that give Animal Crossing much of its charm. There’s a wide variety of possible residents (more than can live in any town at one time), each with their own likes, dislikes, and personalities. Interacting with them can lead to many amusing conversations and optional quests and befriending different villagers is the only way to get certain rare items. These interactions help make players feel like they’re part of a real village with other residents who have their own lives and goals and are quite a lot of fun, despite the lack of any sort of deep plot or backstory.

Animal Crossing also makes use of the GameCube’s internal clock, which ties into numerous features including the weather, yearly holidays, and special characters who visit your village from time to time. Players can also visit each others’ villages to explore, collect and trade items, and even entice village residents to relocate to the other player’s town.

Whether you like trying to hunt down all of the myriads of different items and collectables, or just want to relax with a nice, slow-paced game, Animal Crossing contains more than enough gameplay to keep players busy and entertained for months on end, no matter which activities they enjoy most. It proves beyond a shadow of a doubt that fully player-driven storytelling (most often the domain of serious simulation games and MMOs) can also be used to great effect in simpler, slower-paced titles.

The Weaknesses of Fully Player-Driven Stories

We already discussed some of the difficulties that come with creating a fully player-driven story and also talked about how, barring the creation of some sort of near-human AI, the style can never be perfected in video games, as there will always be some actions that the player is unable to perform. But these are not the only weaknesses to be found.

In many ways, the total player freedom and lack of a structured story – though they are the style’s biggest strength – are a considerable weakness as well. Many players like having structure and want a game with clear-cut goals and a set ending. Although some players enjoy being free to mess around and do what they want, or are at least good at creating goals and a structure for themselves, others often find themselves lost. Faced with too many options, they can’t decide what to do and become stuck and/or frustrated. Others initially enjoy the freedom, but after they spend a little time playing around with the various options and activities, quickly grow bored. With no specified goals to motivate them, they soon tire of the game and move onto other things. Some games, such as MMORPGs, deal with this issue by adding a large variety of game-recognized goals (levels, titles, quest chains, and the like) that the player can pursue or ignore at his or her leisure. This certainly helps and is, in fact, quite effective at hooking some players, but others still find the lack of an ending and complete story structure off-putting and have little interest in completing various arbitrary tasks when there are no real plot elements tied into them. For that type of player, collecting 12 diamonds in order to bribe the prison guard and rescue the princess is fine, but collecting 12 diamonds for 100 experience points and a check mark in his or her quest journal just doesn’t provide the same motivation. Of course, some players are the opposite, and focus little on the story while obsessively completing every quest and earning every title, no matter how pointless, to earn bragging rights and prove their mastery of the game. There’s nothing wrong with either attitude – it’s just important to remember that both types of gamers exist.

Fully player-driven stories are the most player-driven type of storytelling possible. Instead of being built around a main plot, they’re instead composed entirely of a setting (which can include NPCs, backstory, and/or short stories told via quest chains) and rules detailing the way in which the players can interact with that setting. This leaves players free to do what they want when they want and to create an entirely unique story of their own.

However, without a main plot, it’s extremely important to be sure that the setting is interesting and contains enough activities and options to keep the player entertained. A lot of planning also has to go into deciding the rules of interaction so that the nearly infinite number of actions that a real person could take at any given time are narrowed down to those that are most fun and useful within the game. Limiting the options like this is currently the only way to create fully player-driven stories in games, but does impose strict limitations on the player, thereby reducing his or her freedom and control. The only way the style can be perfected is through the use of broader, less-structured systems (such as tabletop RPGs like Dungeons & Dragons) combined with a human moderator who can modify the story as needed based on the player’s actions. Theoretically, a near-human AI program could fill that role, but it’s highly unlikely that such an AI will be created in the near future (if ever).

Although the freedom in fully player-driven stories can’t be matched, it can also spell trouble with regard to attracting players who prefer to have set goals, stories, and/or some kind of basic structure to help them decide how to proceed through the game. MMORPGs, many of which use fully player-driven storytelling, attempt to solve this problem by using things such as titles, character development, and story-based quest chains to give some structure and more of a plot than can be found in games like The Sims and Animal Crossing. However, none of these can replace a true main plot, and although they have proven popular with some players, they fail to interest others, showing that even at their best, fully player-driven stories really aren’t for everyone (as evidenced in Chapter 14).

1. List five games you’ve played that use fully player-driven stories (if you haven’t played that many, just list the ones you have).

2. Pick two games from your list. Do one or both of them have any sort of plot or backstory? If so, in what ways is it conveyed to the player?

3. Pick one of your two games and list the different activities available within the game. Make your list as comprehensive as you can.

4. Does your chosen game have any set goals or accomplishments? If so, make a list of what they are and how to achieve them. Do you feel that these goals are an enjoyable addition to the game? Why or why not?

5. Do you think you would have enjoyed the game more if it included a full main plot? In what ways do you feel that the addition of a main plot would have improved or detracted from the game?