CHAPTER

Five

Making Stories Emotional

One of the hallmarks of a good story is the way it makes the player (or reader or viewer) feel. You want the player to feel fear when the heroes are in danger, triumph when they succeed, and sadness when they fall. Naturally, some people are more easily affected than others. I’m sure you all know someone (whether a friend, family member, or even yourself) who is easily swept up in the moment when playing games, reading books, or watching movies and often screams, laughs, and cries as the story plays out. I’m sure you also know people who can sit through those same stories stone faced with little to no hint of outward emotion, though that doesn’t necessarily mean they aren’t feeling the emotions – just that they’re better at suppressing them. In the end, a good writer can reasonably expect the majority of the audience to feel specific emotions at specific points in the story.

Connecting with the Characters

So why are emotions so important? It’s just a story, right? Yes, but the entire point of stories is to let us experience other places and other lives. When we feel sympathy for a tragic heroine or deep hatred for a villain, it proves just how much a part of the story we’ve become. We’re no longer just observing a fictional event; to us, the place and characters have become alive and real. They’re not strangers on a page – they’re our friends, companions, and enemies, and as such, we truly care what happens to them.

Not all stories achieve this level of involvement. Some never even try and instead strive to be merely enjoyable without forming any sort of complex emotional attachment. And there’s nothing wrong with that. As I’ve said before, there’s room in the world for all types of stories. Heavy emotional tales are good, but at times people just want to sit back and be entertained.

Case Study: Metal Gear Solid 3: Snake Eater

| Developer: | Konami |

| Publisher: | Konami |

| Writers: | Hideo Kojima, Tomokazu Fukushima, Shuyo Murata |

| System: | Sony PlayStation 2 |

| Release Date: | November 17, 2004 (US) |

| Genre: | Stealth Action |

| Other Version: | Metal Gear Solid 3: Subsistence (PlayStation 2, 2006) |

FIGURE 5.1

Snake’s mission requires him to remain alone and unseen.

Metal Gear Solid 3: Snake Eater is the fifth game in the Metal Gear series, but acts as a prequel, trading the near-future setting of the other titles for the Cold War era of 1964. At the start, an American covert agent code-named Naked Snake (a father of sorts to Solid Snake, the hero of most of the other games) is sent into a remote part of the Russian wilderness to help evacuate a Soviet scientist who wants to defect to the United States. However, the mission quickly falls apart when Snake’s mentor, The Boss (a woman revered as the mother of the American special forces), defects, takes two small nuclear warheads with her, and joins Colonel Volgin, leader of a rogue faction within the USSR. In order to prove the innocence of the United States in the resulting nuclear strike and prevent an all-out war, Snake is tasked with stopping Volgin’s plans and eliminating The Boss.

With the exception of the superhuman powers used by a handful of villains and a few instances of technology that seems a little ahead of its time, Snake Eater’s plot remains realistic and historically accurate. But the intricacies of the Cold War, nuclear deterrents, and secret weapon development take backstage to the goals and emotions of the characters themselves.Snake is strongly conflicted about his mission. Though he understands that killing The Boss is necessary to prevent an all-out nuclear war, he’s naturally upset at the thought of murdering his longtime friend and mentor. He also finds himself consumed with the question of why a woman who had dedicated her entire life to the service of her country has chosen to defect. From the mysterious double agent Eva to the members of The Boss’s Cobra Unit (each of which has named himself after the single emotion that consumes him when in battle), and Snake’s helpful yet eccentric radio support team, each character is interesting and memorable. The characters have a goal that drives them and a backstory explaining how those goals came about. In the end, even the more outlandish characters like the electricity-shooting Volgin feel quite real and believable.

FIGURE 5.2

The Boss’s betrayal deeply affects Snake.

In the center of it all lies the relationship between Snake and The Boss, leading to an emotionally charged debate about the importance of loyalty and to whom or what that loyalty should be given before the two engage in their final battle. When the game pauses, waiting for the player to pull the trigger one final time to end her life, the player can feel the conflict and sorrow filling Snake’s mind. Over the course of the game, it has become clear just how close he and The Boss were, and that whatever her reason for defecting, killing her is a mistake – but unavoidable. The shocking revelation that follows, explaining the true goal and purpose of The Boss’s final mission, adds even more to Snake’s and the player’s conflicted feelings, leading up to a highly emotional ending as Snake ignores the honor and accolades given to him by the government to instead stand before The Boss’s grave, saluting the woman who was, above all else, a true patriot.

Players have often cited Snake Eater’s ending as one of the most emotional moments in gaming, yet the ending has such a strong impact only because the rest of the story spent so much time building up the characters and their relationships. Without knowledge of Snake’s feelings, The Boss’s dedication, and the heavy stakes riding on their missions, all of which are carefully explained and developed over the course of the game, the ending would lose much of its impact and nearly all of its emotion. As Snake Eater shows, it’s only by taking significant time and effort to make players care about the characters that any serious emotional connection and impact can be made.

The Fine Line Between Drama and Melodrama

Many of you are likely wondering exactly what melodrama is. Essentially, a melodrama is a story that features clearly defined and highly stereotypical good and evil roles (often so much so that they’re rather ridiculous). For example, a classic melodramatic hero will dress all in white and be the perfect saint and gentleman, kind and compassionate to everyone he meets, without any selfish thoughts or vices. His enemy, the classic melodramatic villain, will dress in black with a monocle and curly mustache and be completely mean, rotten, and dishonest in everything he does. A true melodrama rarely – if ever – contains moral shades of gray, and the villain always loses. Classic examples of melodrama include the 1965 film The Great Race and many old cartoons such as Wacky Races (itself inspired by The Great Race).

Nowadays, however, full melodramas are extremely rare and the term is more often used to describe plot twists and overacting that are taken to the point of near absurdity. Soap operas, for example, are often called melodramatic. In the realm of games, FINAL FANTASY IV can be considered somewhat melodramatic as well. The most blatant examples of melodrama in the game are the way the hero’s party members frequently sacrifice themselves in heroic ways in order to save their friends, only to turn up later in the game alive and well (with one notable exception). The revelation that hero Cecil’s former best friend turned enemy, Kain, is being controlled by a villain named Golbez, who (it is later revealed) is actually Cecil’s brother, is not evil, and is being controlled by the real villain Zemus (who, depending on how you interpret the ending, can be considered to be merely a pawn of the dark spirit Zeromus) is rather melodramatic as well.

Though melodrama is often looked down upon, there’s nothing necessarily wrong with using it. Soap operas maintain loyal followings despite their over reliance on clichés and melodrama and some FINAL FANTASY fans still consider IV to be the best entry in the series. Melodrama can also be put to great use in comedies, where overacting and ridiculous plot twists can make for a lot of hilarious situations. If you’re trying to tell a particularly deep and moving story, however, too much melodrama is almost certain to cause a negative impact.

To avoid melodrama, it’s important to make your characters act and speak in believable ways. I previously explained how it’s important that characters don’t underreact to events; it’s just as important that they don’t overreact, either. For example, though the death of a loved one could potentially lead to an angry, tearful lament, something less traumatic such as a stolen wallet or broken arm probably shouldn’t. Also, try to avoid reusing the same plot twist multiple times in a story, especially if it’s a clichéd one. Every villain doesn’t need to be related to the hero or be mind controlled by someone else. Once is usually enough!

Of all the emotional reactions people can have to stories, being moved to tears is often seen as the most intense and hardest to achieve. As discussed earlier, some people react to stories more easily than others and cry often, but creating a story that can actually make most of its audience cry is a very difficult thing. Not only does the event have to be particularly sad and moving, but the audience also needs to have formed a very strong bond with the characters for them to feel that sadness strongly enough that they themselves start crying. Though very hard to achieve, creating a story that can make the majority of its audience cry is a mark of good writing and character design.

Always Be Specific

One common mistake young writers make when they design characters is to make them general instead of specific. They fear that if the character is too specific, it will feel to the audience as if this is someone so unique that they couldn’t possibly relate to them which will alienate the character from the audience. Nothing could be further from the truth.

One very unique character in recent film history is Forrest Gump. He is perhaps one of the most unique and quirky characters to inhabit modern cinema, yet the film was a big hit and the character was universally hailed as a great hero and extremely likeable. To a large part, that was due to the portrayal of the character by Tom Hanks, as he delivered the performance truthfully and honestly. But the biggest success of the character was his humanity, expressing his emotions through his actions, his inability to be brave except when put to the test, and his emotional honesty (again when forced). I’d bet that when his character was described in early meetings, there was great concern people wouldn’t like him or be able to relate to him. But his unique, specific character was perhaps the greatest charm of the film.

—Chris

Before we go any further I should probably point out that although good stories can make their audience cry, a story doesn’t have to make people cry in order to be good. There are many excellent stories that simply don’t have the type of extremely sad and emotionally charged scenes that could bring someone to tears. These scenes aren’t missing because the writer wasn’t good enough to create them, but simply because they aren’t necessary for the story. For example, though many people consider the original Star Wars trilogy and Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone to have excellent stories, no one would say that they’re the types of stories that should make you cry (some of the later Harry Potter books and Star Wars movies, perhaps, but not these titles in particular). However, I’ve yet to hear anyone deride or criticize them for not trying to make their audience cry. Such tearful scenes don’t fit within those stories, so they aren’t there – nothing strange or unusual about it.

In the end, though, making people cry is often considered the hallmark or pinnacle of good storytelling. So if you ask people who are critical of video game storytelling (whether inside or outside the game industry) why game stories aren’t just as good as those in books or films, you’ll probably hear the response, “Because they don’t make you cry.” But is this really a valid criticism? As I just explained, it’s perfectly possible to tell an excellent story without making people cry. Furthermore, why is it so easy to believe that games can’t move people to tears just like books or movies? If games don’t make you cry, that doesn’t mean game storytelling is poorly done or immature – it just means that you’re playing the wrong games.

Sure, you’re unlikely to see anyone burst into tears while playing Counter Strike or Super Mario Bros., but as well made and popular as those games are, they aren’t in any way known for their deep, emotional storylines. Similarly, most books and movies don’t make people cry either – it’s all about looking at the right titles. A bit of time spent on game message boards or talking to gamers will reveal that many games have in fact made people cry. The aforementioned Metal Gear Solid 3: Snake Eater is frequently mentioned, as is its sequel Metal Gear Solid 4: Guns of the Patriots (which we’ll talk about in Chapter 7). Shadow of the Colossus and various FINAL FANTASY games (especially VII, X, and CRISIS CORE) have also brought many players to tears. And those are just a few of the most popular examples.

For a more personal example, and to avoid embarrassing anyone I know, here are my own experiences on the matter. As I said in the first chapter, I love stories. At pretty much any given time, I’m in the middle of at least one book, one game, and one television show – the vast majority of which I pick up primarily for their stories. And as my friends and family can attest, I really get into the stories I read, watch, and play and can easily spend hours discussing them and mulling over their characters, twists, and implications. Despite that, I don’t tend to show much emotion when reading, watching, or playing. I feel the emotions – I just tend to keep my feelings inside. There are plenty of stories that have left me happy and elated and lots of others that tied my stomach in knots and cast a cloud of depression over the rest of my day, but it’s extremely rare for a story to hit me so hard that I actually cheer, shout, or cry because of it. In fact, over the last ten years, I can only think of four stories that have made me cry (though several others came very close). One was a book, one was a movie, and two were video games (Metal Gear Solid 4 and CRISIS CORE, if you’re curious). Because of both my own experiences and the things I’ve heard from so many other gamers, I simply can’t believe that game storytelling isn’t good enough to make people cry. Anyone who thinks that way clearly needs to play more games.

Case Study: CRISIS CORE – FINAL FANTASY VII

| Developer: | Square Enix Co., Ltd. |

| Publisher: | Square Enix, Inc. |

| Writers: | Hideki Imaizumi, Kazushige Nojima |

| System: | Sony PSP |

| Release Date: | March 25, 2008 (US) |

| Genre: | Action RPG |

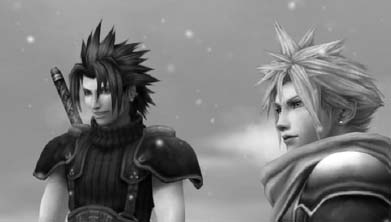

FIGURE 5.3

CRISIS CORE: Prior to Sephiroth’s betrayal, he and Zack often worked together. © Square Enix, Co., Ltd. All rights reserved.

Even after thirteen years, FINAL FANTASY VII (which we’ll discuss in Chapter 6) remains one of the most popular and beloved entries in the series. This continued popularity eventually led to a collection of spin-offs, prequels, and sequels dubbed COMPILATION OF FINAL FANTASY VII, which included the CG movie FINAL FANTASY VII: ADVENT CHILDREN and the PlayStation 2 game DIRGE OF CERBERUS: FINAL FANTASY VII. Though some parts of the compilation met with mixed reviews, CRISIS CORE – FINAL FANTASY VII received near-universal acclaim and is generally considered to be the best entry in the entire compilation. In addition to featuring impressive graphics and music, CRISIS CORE’s fast gameplay and moving story were also the subject of considerable praise.

Set several years before the beginning of FINAL FANTASY VII, Crisis Core – FINAL FANTASY VII tells the story of Shinra soldier Zack Fair. Zack was first introduced in FINAL FANTASY VII though relatively little information about him was revealed. Going into CRISIS CORE, fans knew that Zack was a Soldier First Class (the highest rank of Shinra’s elite Soldier division and the same one held by FINAL FANTASY VII’s villain Sephiroth) and that he was present during the destruction of the town of Nibelheim. After leaving Soldier, Zack was latter gunned down by three Shinra troopers when returning to Midgar.

One of the most powerful aspects of CRISIS CORE – FINAL FANTASY VII’s story is that many players enter into it fully knowing Zack’s eventual fate. However, over the course of the game Zack is revealed to be not just another soldier, but a caring young man determined to help others and be a hero, as he feels every Soldier should be. As Zack completes missions and rises through the ranks, growing closer to attaining his dream, he makes friends and enemies, faces a shocking betrayal, and is even faced with the dark sides of Soldier and the Shinra Company. Zack’s reactions to each of these life-changing events shake his faith in others and himself, but despite it all, he still manages to cling to his beliefs and push on, determined to be the kind of hero his family, friends, and former mentor Angeal can be proud of. Because of his determination, friendly attitude, dedication to his duty and his friends, and the way he handles his many trials and disappointments, Zack is a very likable character, making the knowledge of his eventual fate all the harder to accept.

FIGURE 5.4

Zack passes on his sword and dreams to Cloud, the hero of FINAL FANTASY VII. © Square Enix, Co., Ltd. All rights reserved.

As the game nears its close with the traitorous Genesis defeated, Zack and Cloud, now on the run from Shinra forces who wish to completely bury the truth about what happened in Nibelheim, make their way toward Midgar. The experiments performed on them have left Cloud in a near vegetative state, but Zack refuses to abandon him and even spends the ride to Midgar describing how he plans to earn enough money to support them both until Cloud recovers. Unfortunately, it’s not to be, as Zack is thrust into an impossible final battle in a desperate attempt to win freedom for himself and Cloud (a tense and epic event, only the smallest part of which was shown in FINAL FANTASY VII). In a very nice touch, the player is allowed to control Zack during this last hopeless fight, significantly increasing his immersion and personal investment in the event. The combination of Zack’s inevitable fate, his desperate will to survive and the player’s will to keep him alive (as demonstrated in the final battle), the haunting music, and Zack’s final words make for one of the most emotional moments I’ve encountered in any story – and prove that games do indeed hold the power to make people cry.

A good story works on the player’s emotions, causing him or her to feel joy and sadness along with the heroes. However, for players to become emotionally invested in a story, they have to connect with the characters, which is why it’s so important to create deep and believable heroes and villains. As important as it is to create an emotional experience, you need to ensure that you don’t go over-board with the big emotional moments and turn your story into a melodrama.

When a player has a deep emotional investment in a story, certain events can even move that person to tears. Making people cry is a mark, but not a requirement, of good writing. Though powerful, not every story needs a tearjerker scene. Though some people argue that game storytelling hasn’t reached the point where it can make people cry, many gamers will be quick to refute such claims. Games, just like every other form of storytelling, can make you cry – you just need to play the right ones.

1. List three games in which you felt a particularly deep connection with one or more characters. What was it about those characters that appealed to you?

2. What do you have in common with those characters (upbringing, personality, beliefs, etc.)? In what ways are you different?

3. Can you think of any games you’ve played that were especially melodramatic? Briefly describe the three most melodramatic stories and discuss how you would improve them.

4. List some stories (video games or otherwise) that have made you cry. What parts of them did you find particularly moving and why?