CHAPTER

Two

A Brief History of Storytelling in Games

Before we start seriously looking at the nuts and bolts of game storytelling, I think it’s important to pause and take a look at the past. Games have come a long way since the days of Pong – and it’s not only the graphics, sound, and gameplay that have improved, but the storytelling as well. It’s interesting to trace the history of game stories as they evolved from a few lines of text or a couple of pixelated cut-scenes to the complex high-definition multimedia experiences of today and look at the titles that helped shape the eras in which they were released. Of course, a complete study of game history would require an entire book of its own, but we have time to take a look at a few of the highlights. In the end, no matter how much games continue to grow and change, they’ll still be partially shaped by the events and titles of years past. As the saying goes, “To understand the future, one must first look to the past.”

The Beginnings of Game Stories

In the earliest days of video and computer gaming, there were no such things as stories. Beginning in 1962 with the creation of Spacewar! (which was later renamed Computer Space and released as one of the earliest arcade games in 1971), the first wave of video and computer games could do little more than move a few dots and lines around a screen. Not only could they not display long lines of text, but they lacked the memory required to store it. The explosion of the arcade market following the release of Pong in 1972 did little to improve the situation. Due to serious hardware and memory constraints, any story was limited to a few of lines of text printed on the side of the arcade cabinet. Though some arcade games managed to fit in a few words or a short cut-scene or two, it wasn’t until the late 1970s (for computer games) and the early 1980s (for arcade games) that things began to change.

| Developer: | Nintendo |

| Publisher: | Nintendo |

| Designer: | Shigeru Miyamoto |

| System: | Arcade |

| Release Date: | 1981 (US) |

| Genre: | Platformer |

Nintendo’s Donkey Kong was a game of firsts. It was the first game designed by industry legend Shigeru Miyamoto (who also created many other Nintendo series, including Super Mario Bros., The Legend of Zelda, and Pikmin), the first game to feature the iconic Mario (then named Jumpman) and Donkey Kong, the first platformer game (or possibly the second, depending on whom you ask), the first game to include multiple level types – and Nintendo’s first big hit. It was also the first game to use cut-scenes to visually portray a complete story. Though Donkey Kong wasn’t the first game to tell a complete story (it was predated by early computer text adventure games, which we’ll be discussing shortly) or the first game to use cut-scenes (a few other arcade games came first), it was the first to combine the two elements and marked the beginning of a gradual movement toward more story-based games in the arcade market.

Donkey Kong’s story is told over the course of four levels. As the game begins, we see the giant monkey Donkey Kong grab a woman (originally known simply as Lady but later renamed Pauline) and climb to the top of a tower. Mario (Jumpman) gives chase but Donkey Kong damages the structure and proceeds to sneer down at him. At this point, the level begins and the player is tasked with guiding Mario to the top of the tower while dodging rolling barrels thrown by Donkey Kong. Throughout the course of the level, Pauline frequently cries for help, adding to the urgency of the situation. Should the player manage to reach her, Mario and Pauline stare into each other’s eyes and a heart appears above their heads. However, that heart is soon broken as Donkey Kong grabs Pauline and makes off with her. Levels 2 and 3 are similar, with Mario pursuing Donkey Kong and Pauline across increasingly complex and difficult areas. In the fourth and final level, Mario is able to remove the supports from the building, causing Donkey Kong to plummet painfully to ground and allowing Mario and Pauline to finally reunite.

Although Donkey Kong’s story may seem simple by modern standards, it was the first arcade game to add any sort of background information or story to the game itself rather than just printing it on the cabinet. It was also the first game of any kind to tell a story using a series of cut-scenes. It would still be a few years before stories started becoming an important part of arcade and console games, but Donkey Kong was the game that started it all.

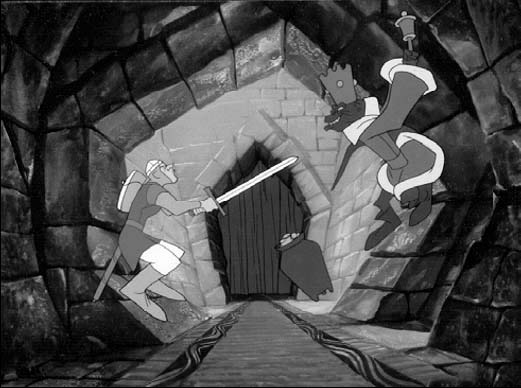

FIGURE 2.1

Dirk the Daring is off to rescue the princess in Dragon’s Lair. Image courtesy of Bluth Group, Ltd. (1983), Don Bluth.

Two years later, in 1983, Dragon’s Lair took things considerably further.

Created by former Disney animator Don Bluth, Dragon’s Lair used movie-quality animation to tell its version of the classic princess-in-distress story with players helping bumbling knight Dirk the Daring on his quest to rescue Princess Daphne from an evil dragon. The use of laser discs for storage, combined with beautiful prerecorded video sequences and voice acting, allowed Dragon’s Lair to achieve a level of audiovisual quality and storytelling that it would take other games years to reach. However, the heavy reliance on prerecorded video did limit Dragon’s Lair’s gameplay. With each obstacle Dirk faced, players could do nothing more than choose from one of several prompts and then watch the predetermined outcome, boiling the gameplay down to a combination of luck and memorization and severely limiting replay value. Despite its flaws, Dragon’s Lair remains an important title in the history of game storytelling and allowed gamers a very early glimpse at what the future of gaming could hold.

FIGURE 2.2

Dirk vs. the Lizard King. Image courtesy of Bluth Group, Ltd. © (1983), Don Bluth.

Text Adventures and Interactive Fiction

In 1976, a few years before Donkey Kong’s debut, computers saw their first story-based game with the creation of Colossal Cave Adventure (also known as Colossal Cave and, more commonly, Adventure), the first text adventure or IF (interactive fiction) game. Though the original version ran only on a massive mainframe computer, rapid advancements in technology soon allowed Colossal Cave and other IF games to reach the consumer market.

Text adventure titles were, as their name suggests, entirely devoid of graphics. Areas, items, and characters were described to the player via blocks of text and the player interacted with the game by entering simple words or phrases such as “go east,” “open door,” and “use sword.” As computers of the day lacked the power and memory necessary to spell-check or otherwise verify multiple variations of phrases, they could usually understand only one or two versions of each command. So although “use sword” might produce the desired result, “swing sword” would instead display an error message, leaving the frustrated player to try and figure out why a seemingly reasonable action wasn’t recognized. Many text adventures were also famous for their difficult gameplay, which was often based around complex maze-like areas and tricky inventory-based puzzles. Character deaths also tended to be a frequent occurrence, often as the result of seemingly benign actions, and in some games it was even possible to unknowingly perform a wrong action and render the entire game unwinnable, something that the player might not discover until hours later. All of these elements are frowned upon in modern gameplay, but at the time, they were not only acceptable but expected.

The stories in text adventures varied wildly, covering many different genres and writing styles. Though most cast players as a nameless generic hero who has to explore a strange area, others placed more of a focus on character development and plot-driven stories. From an interactivity standpoint, interactive traditional stories, multiple-ending stories, and branching path stories were all frequently employed, and a few titles even neared the level of freedom and choice available in open-ended stories (a summary of the differences between these storytelling styles can be found in Chapter 6, with in-depth explanations in Chapters 7 through 11). Text adventures enjoyed a brief golden age during the late 1970s and early 1980s, but as computer technology continued to advance, they were soon replaced by more visually pleasing graphic adventure games. They retain a small but dedicated fanbase that continues to make new text adventure games under the IF moniker.

The first computer RPGs also began appearing in the early 1980s starting with Ultima I: The First Age of Darkness in 1981. Though their stories initially lacked the depth of those found in the better text adventures, they evolved quickly, offering better sound and graphics along with deeper gameplay and more complex storylines, eventually helping inspire famous console RPGs such as DRAGON WARRIOR (1986) and FINAL FANTASY (1987).

Case Study: Colossal Cave Adventure

| Designers: | William Crowther, Don Woods |

| Publisher: | CRL |

| System: | PDP-10 (later ported to a variety of other computers) |

| Release Date: | 1976 (original version), 1977 (updated version) |

| Genre: | Text Adventure |

Created as a hobby by caving enthusiast William Crowther and significantly expanded the following year by Don Woods, Colossal Cave Adventure marked the start of the adventure game genre and was the first game to feature a full in-game story.

>You are standing at the end of a road before a small brick building. Around you is a forest. A small stream flows out of the building and down a gully.

And so it begins. The story itself is pretty simple. You play as a generic hero (or yourself, if you prefer) who finds himself standing in the woods (described in the previous text quote). Exploring the building will turn up an all-important lamp and several other useful items; after a little more wandering around, you’ll come across the entrance to a cave. Loosely based on the layout of Kentucky’s Mammoth Cave, the cavern is a vast maze of twisty little passages and strange rooms. An assortment of dangerous creatures roam the area, ranging from the realistic (a bear) to the fantastical (dragons, dwarves, and so on), but there is also a plethora of fabulous treasures to be found. Of course, many of the treasures (as shown by the following quote) are either guarded or otherwise difficult to obtain.

>You are inside a barren room. The center of the room is completely empty except for some dust. Marks in the dust lead away toward the far end of the room. The only exit is the way you came in.

> There is a ferocious cave bear eying you from the far end of the room! The bear is locked to the wall with a golden chain!

The solution to this bear room involves using some food (which you may or may not have picked up earlier) to feed and pacify the bear, unlocking the golden chain (if you previously found the keys), taking the chain (it’s a treasure), and then getting the bear to follow you, as he’ll come in handy later on.

Though Colossal Cave almost fits the mold of a fully player-driven story, just turning you free to explore and do as you please, there’s a loose plot thread strung throughout the game about the mystery of the caves and why all these strange things are inside. Also, although the game doesn’t tell you exactly what your goal is other than exploration and survival, there is an ending, trigged by collecting all the treasures and solving a final puzzle. However, as your character has very limited inventory space and is hounded by treasure-stealing pirates and other hazards, the treasures have to be safely stored in the building from the start of the game (another thing that the player must figure out on his or her own).

As with many other text adventures, it’s possible to make the game unwinnable by accidentally losing or destroying important items. Completing Colossal Cave without the use of a guide requires playing and restarting the game many times while making a map of its vast and confusing tunnels. The game also features a point system with a maximum possible score that can be obtained only by collecting and keeping every treasure with no deaths before your lamp runs out of power (which puts an end to your explorations, unless you previously traded a certain treasure for extra batteries), a feat that requires detailed knowledge of the cave and some careful planning to achieve.

Many modern gamers may scoff at the lack of graphics and find Colossal Cave’s unforgiving gameplay frustrating, but it provides a fascinating look at the start of the adventure game genre, and its twisty passages and imaginative chambers are just as engrossing now as they were over 30 years ago. If you’re interested in exploring the roots of PC gaming, you can find out more about Colossal Cave Adventure and download many different free versions of the game at http://www.rickadams.org/adventure/. (I recommend the Windows version of Adventure 3, which, aside from being based on the most popular release, also runs well on most current computers.)

RPGs, Adventure Games, and the Growing Importance of Stories

Today, games with deep stories can be found in every genre, but from the late 1980s until the mid 1990s, the stories in most games tended to be simple variations of the “rescue the princess” or “save the world from the evil villain” themes. Though there were exceptions, deep, complex stories were mostly limited to American RPGs and adventure games (on the PC) and Japanese RPGs (on consoles).

On the PC side, newer and better hardware allowed text adventure games to transform into graphic adventure games. Though originally nothing but text adventures with simple static artwork, adventure games soon grew to include detailed animated graphics and more user-friendly point-and-click interfaces. The so-called golden age of PC adventure games featured many excellent titles but was primarily dominated by two developers. The first was Sierra, with popular series, including King’s Quest, Space Quest, and Leisure Suit Larry. The second was LucasArts, with games such as The Secret of Monkey Island, Sam & Max Hit the Road, and Day of the Tentacle. Many of these titles are still as fun and hilarious as they were when first released and are available in various classic game bundles and from downloadable game services.

Adventure games from this era were often characterized by bright, colorful graphics and humorous storylines. The gameplay tended to emphasize a mix of conversations, item collection, and inventory-based puzzles. Though interactive traditional stories were the most common, some multiple-ending and a few branching path stories were used as well. Though far less frustrating than many text adventures, point-and-click adventure games often featured at least a few puzzles with highly illogical solutions and frequently forced players to engage in a “pixel hunt,” which refers to the process of moving and clicking the mouse all over a screen in hopes of finding a missed item or other important “hotspot.” Although early point-and-click adventure games also retained the frequent deaths and unwinnable scenarios that plagued text adventures, they soon began to move away from that (led by LucasArts), eventually reaching the point at which it was impossible to become permanently stuck and there were few, if any, ways to die.

The genre later underwent another significant change in 1993 with the release of Cyan Worlds’ classic adventure game Myst. In a significant change of style from the games that had come before it, Myst used a first-person perspective and made the player (instead of a developed character) the hero. It also replaced the cartoon-like 2D graphics with highly detailed 3D scenes, emphasized ambient sounds rather than a full musical score, and made its puzzles environmental in nature rather than inventory-based. Myst also took a much different approach to its story. After being transported to the island of Myst by a strange book, the player is given free rein to explore and try to solve the island’s many tricky puzzles. The story is, in contrast to most adventure games of the time, very serious and told primarily through a series of notes and journals scattered about the islands, leaving players to track down and piece together the clues and determine why the island of Myst and the other ages it links to are deserted and how the two brothers Sirrus and Achenar have become trapped inside a pair of unusual books.

Myst’s sharp departure from the formula used by past adventure games was a surprising success, making it the bestselling PC game of all time until 2000 (when it was unseated by The Sims, which we’ll discuss in Chapter 11) and spawning several sequels and a massive number of clones and copycat games. The Myst style continued to dominate the PC adventure game genre for several years until the steady rise of FPS, MMO (massively multiplayer online), and strategy games took over the PC market and forced the adventure genre into near dormancy.

Throughout all this, PC RPGs continued to evolve as well, led by the Ultima and Might and Magic series, though the changes were nowhere near as drastic as those seen in the adventure game genre. Primary improvements included better graphics, the switch to a first-person perspective (for some but not all titles), and increasingly complex gameplay systems, many of which were based heavily on the classic tabletop RPG Dungeons & Dragons. From a story perspective, the increase in available memory allowed for more text, which led to longer in-game conversations and branching dialog systems in which the player could frequently choose between multiple responses to questions and inquiries posed by nonplayer characters (NPCs). An interesting thing to note is that although console RPGs (which we’ll be discussing in a moment) focused primarily on character-driven stories featuring well-defined heroes and villains with complex personalities and backstories, PC RPGs tended to feature generic heroes and focus more on exploration and character building with broader yet simpler storylines.

Meanwhile, as personal computers were still relatively new, complicated, and expensive, consoles continued to dominate the game market. The NES (Nintendo Entertainment System) and later Super NES and Sega Genesis were vast improvements over earlier systems such as the Atari 2600, allowing for games with better graphics, more varied gameplay, and longer and deeper stories. Though most of the popular genres of the time, like platformers and action games, kept their stories short and simple, the storytelling in RPGs rapidly improved. Unlike PC RPGs, which were developed in the United States, console RPGs were primarily developed by Japanese companies such as Square and Enix (which eventually merged to form Square Enix). No one would call the stories in RPGs such as the first DRAGON WARRIOR or FINAL FANTASY masterpieces, but their epic quests and twisting tales stood in stark contrast to the brief cut-scenes and scattered lines of dialog found in other games of the time. In addition, some games such as Castlevania II: Simon’s Quest began to introduce multiple-ending storytelling, allowing players to have a say in how their stories ended.

When the Super NES and Sega Genesis began their battle for living room dominance, RPG makers took advantage of the increased power and memory to hone their craft and tell increasingly rich stories. Square led the charge, creating many classic titles such as FINAL FANTASY VI (originally released in the United States as FINAL FANTASY III), CHRONO TRIGGER (which we’ll talk about more in Chapter 8), and SECRET OF MANA, which are still considered by many to feature some of the best gameplay and stories the genre has ever seen. FINAL FANTASY VI in particular is known for its diverse and interesting cast of characters (including fan favorite villain Kefka) and deep story, which touched on many mature issues such as death, suicide, and teen pregnancy. Other notable titles include Nintendo’s Earthbound and Super Mario RPG, Enix’s Illusion of Gaia and Ogre Battle, and Sega’s Phantasy Star series. Although interactive traditional stories still dominated the period, CHRONO TRIGGER used multiple-ending storytelling to great effect and Ogre Battle featured a complex branching path story.

Unfortunately, though console RPGs were huge hits in Japan, with new Square and Enix titles frequently resulting in long lines of fans camping out to await their release, they remained a niche market in the United States. Whether this was due to a lack of advertising, their complexity, or their radically different gameplay styles when compared to the market dominating platformer games is hard to say. Regardless of the reasons, this situation led to many Japanese developers refusing to release major RPGs, even extremely popular ones, in the United States (such as FINAL FANTASY II, III, and V, FRONT MISSION, STAROCEAN, and DRAGON WARRIOR V and VI). Others (such as FINAL FANTASY IV) were significantly edited or scaled back to make them “easy enough” for American gamers. Fortunately, the stories mostly remained intact (aside from occasional translation issues) and began to show U.S. gamers that game stories could contain the same depth and complexity found in novels and films, though it would be a few more years until gaming’s story revolution truly began.

Case Study: FINAL FANTASY IV

| Developer: | Square Co., Ltd. |

| Publisher: | Nintendo of America, Inc. |

| Writers: | Hironobu Sakaguchi, Takashi Tokita |

| System: | Super Nintendo |

| Release Date: | November 23, 1991 (US) (originally called FINAL FANTASY II) |

| Genre: | RPG |

| Other Versions: | PlayStation (included in FINAL FANTASY CHRONICLES, 1997), Game Boy Advance (2005), Nintendo DS (2008), Wii Virtual Console (2010) |

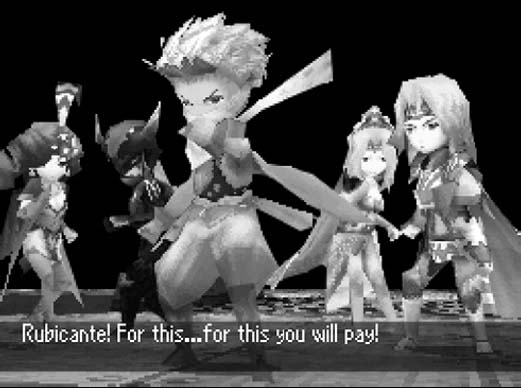

FIGURE 2.3

The cast of FINAL FANTASY IV (from the DS version). © Square Enix, Co., LTD. All Rights Reserved.

Square Enix’s FINAL FANTASY series is one of the most well-known RPG franchises the world over. Unlike its biggest competitor DRAGON QUEST (also by Square Enix), which focuses on traditional old-fashioned RPG adventures, the FINAL FANTASY series has always striven to push the envelope, try new things, and advance the genre and the game industry as a whole. Many of the gameplay elements that were first introduced in FINAL FANTASY games have gone on to become standard features in hundreds of other titles. FINAL FANTASY games (especially the numbered “main series” entries) have developed a reputation for cutting-edge graphics, sweeping musical scores, new and innovative battle and character development systems, and – most importantly – memorable characters and deep, complex storylines. Because of their reputation and the impact many of their stories have had throughout the game industry, we’ll be discussing several FINAL FANTASY titles throughout the course of this book.

Originally released in the United States as FINAL FANTASY II (due to FINAL FANTASY II and III not being released outside Japan), FINAL FANTASY IV was a groundbreaking RPG that paved the way for many future titles. Notable new features in FINAL FANTASY IV included a longer quest and larger world than past games, an Active Time Battle system (now standard in many RPGs), and a far longer and deeper story with a wide cast of unique and fully developed characters.

It should be noted that the original U.S. release featured significantly reduced difficulty in an effort to better appeal to U.S. gamers and had all religious references removed to comply with censorship requirements. Due to space constraints, certain minor plot and backstory elements were removed as well. Later rereleases and remakes, however, are truer to the game’s original Japanese version.

FINAL FANTASY IV tells the story of Cecil, a dark knight serving the kingdom of Baron. Recently, the king of Baron has been behaving extremely erratically and attacking other nations for reasons that are flimsy at best. Cecil questions his motives, only to find himself stripped of his rank and sent along with his best friend Kain to deliver a package to a nearby village. The package, however, turns out to be a trap that destroys most of the village. Horrified by what he has done, Cecil leaves Baron, setting off with the last survivor of the village, a girl named Rydia. Upon learning that the king of Baron is trying to collect the world’s elemental crystals, Cecil decides he must do his best to protect them. Along the way, he is joined by numerous companions (many of whom later sacrifice themselves to save the rest of the party), is forced to confront his own dark past, and discovers that both the king and his friend Kain are being manipulated by a man named Golbez, who is using them to further his own evil schemes. And that’s just the beginning.

FIGURE 2.4

FINAL FANTASY IV’s plot can get a bit melodramatic (from the DS version). © Square Enix Co., Ltd. All rights reserved.

By modern standards, FINAL FANTASY IV’s plot is a bit on the melodramatic side, with all the mind control, heroic sacrifices, and “I am your father”–type moments. However, many fans still consider it to be their favorite entry in the series. Also, in terms of both length and scope, FINAL FANTASY IV greatly surpassed previous console RPGs and also featured characters with far more developed personalities and backstories, making it a truly groundbreaking title in the history of game storytelling.

The Cinematic Evolution of Game Stories

Video game storytelling started to first hit its stride in the RPGs and adventure games of the late 1980s and early 1990s, but it wasn’t until the late 1990s that story-based games began to break out of their niches and spread across all genres. Due to the efforts of several groundbreaking titles, a far wider variety of gamers started to appreciate and desire games that had not only good graphics and gameplay, but good stories as well.

Though the late 1990s and early 2000s were a great time for storytelling in console games, PC gamers weren’t so lucky. With the rise in popularity of FPS, RTS, and sim games (none of which were well known for their stories), adventure games and RPGs lost quite a lot of their popularity. Adventure games were hit particularly hard, though a few good titles, such as Myst III, were released during that period. Meanwhile, Bioware and Black Isle managed to keep the PC RPG genre alive with classic games like Baldur’s Gate, Neverwinter Nights, and Planescape: Torment, and begin to move the genre more in the direction of open-ended stories. There were also a handful of good story-based games released in other genres, such as the cult classic action game Dues Ex, but they were more the exception than the norm.

While story-based games were losing ground on the PC, the exact opposite was happening in the console market. With a new generation of consoles warring for supremacy, games were once again evolving at a rapid pace. There were many great games released on both the Sega Saturn and Nintendo 64, but it was newcomer Sony’s PlayStation that won the fight and helped advance game storytelling toward its current state. Armed with a stronger processor and far more storage space than anyone could have dreamed of back in the days of cartridge-based systems, developers were able to make many groundbreaking titles for the PlayStation, two of which in particular revolutionized the way game stories were told.

The first was Square’s FINAL FANTASY VII. No longer content with appealing only to a niche market and armed with the most graphically impressive game of its time and a massive marketing budget, Square was determined to replicate their success in Japan in the United States. Due to a combination of amazing graphics, excellent review scores, and the massive media blitz surrounding its launch, FINAL FANTASY VII was a runaway success, selling millions of copies. It also introduced many U.S. gamers to RPGs, effectively bringing the genre into the mainstream and paving the way for a steady stream of Japanese RPGs over the following years. We’ll be discussing FINAL FANTASY VII’s story in depth in Chapter 7, but for now know that it continued to evolve the formula used in past titles and featured an epic globe-spanning quest filled with one of the most memorable casts of characters to be found in the entire series.

In addition to greatly increasing the popularity of RPGs and providing one of gaming’s best-loved stories, FINAL FANTASY VII also introduced many gamers to full-motion videos (FMVs). As opposed to normal in-game graphics, FMVs are computer-animated movies that are created and rendered ahead of time. Although they can’t be interacted with, they allow for a far greater level of detail than is otherwise possible. Though FINAL FANTASY VII’s FMVs seem rather crude by today’s standards (or even when compared to those of its sequel, FINAL FANTASY VIII), they were cutting-edge for their time and allowed the artists to show important story scenes in far more detail than would have otherwise been possible, allowing players to accurately read the characters’ body language and facial features, making them feel far more real and alive, and adding considerable impact to the game’s biggest moments.

FMVs proved so popular and effective that many developers began incorporating them into their own games, starting a trend of highly cinematic game storytelling. Even now, FMVs continue to remain an important part of game storytelling, though as graphic quality continues to improve, the line between normal in-game graphics and FMVs is rapidly shrinking.

Though FMVs were an important part of the puzzle, game storytelling was still missing a crucial element required for cinematic storytelling: voices. Voicing acting had been used sporadically in video games for years, but the limited memory capacity on cartridges, discs, and arcade boards made it highly impractical. Even with the launch of the PlayStation and Saturn, with their high-capacity CDs finally offering enough storage space for voice-overs, most early game voice acting was brief and amateurish. It took another big game (Metal Gear Solid, which we’ll discuss momentarily) to show the industry how much quality voice-overs could add to a game.

Multiple-ending stories began to become increasingly more common during this time as well, with games like Metal Gear Solid and Blood Omen: Legacy of Kain (which will be covered in Chapter 8) helping to popularize the concept. Developers also continued to experiment with branching path stories in games such as FRONT MISSION 3 (covered in Chapter 9).

Case Study: Metal Gear Solid

Designer Hideo Kojima’s games are known for several things, including their excellent gameplay, clever boss battles, deep twisting stories, numerous hidden jokes, and infamously long cut-scenes. His most popular work is the long-running Metal Gear series. Though it began in 1987 on the MSX2 and NES, it wasn’t until the release of the third entry, Metal Gear Solid (MGS), that the series became particularly well known. Featuring a complex and mostly believable near-future plot with full voice acting and unique gameplay with an emphasis on stealth and cunning over straight-up action, it become a huge hit and went on to inspire many other stealth action games.

Kojima worked very hard to make the world of MGS as realistic and believable as possible. Though it lacked the FMVs and prerendered backgrounds of FINAL FANTASY VII, an enormous amount of attention was paid to the graphics to ensure that everything from the buildings to the characters came across as realistic and believable.

Aside from a couple of super-powered villains, the story is also very firmly rooted in the real world. The tale begins with Solid Snake, a retired government special forces agent, called in for one last job. The new members of Snake’s old unit (Foxhound) have gone rogue, taking over a remote Alaskan military base and with it, one of the government’s most secret weapon projects, the bipedal-nuclear-equipped tank dubbed Metal Gear Rex, while also securing several high-ranking hostages. Foxhound is using Rex to blackmail the government, demanding the remains of the legendary soldier Big Boss (a.k.a. Naked Snake from Metal Gear Solid 3, which we’ll talk about in Chapter 5). Due to Snake’s past connections to both Big Boss and Metal Gear, and his skill at infiltrating and destroying enemy bases single-handedly, the government sees him as their only hope of stopping Foxhound. However, there are a number of important events going on behind the scenes, and over the course of his mission, Snake is faced with a complex web of plots within plots that could put even the best spy novels to shame. Featuring deep themes including love, war, and the dangers and potentials of nuclear weapons and genetic engineering, the story of MGS remains both emotionally moving and intellectually intriguing.

Despite being on a stealth mission, Snake meets many characters along the way, including allies like the captured soldier Meryl Silverburgh and Rex’s designer Hal “Otacon” Emmerich, and enemies including Russian spy Revolver Ocelot and the mysterious Foxhound leader Liquid Snake. He’s also backed up by a radio support team that he can contact at almost any time to learn more about his mission, weapons, and surroundings, or just to chat. The sheer number of these mostly optional conversations is so enormous that the average player will hear few, if any, repeats. In addition, every line of dialog in the game from important conversations to minor radio banter was recorded by a superb cast of voice actors. The emotions that couldn’t be shown in the character models (as impressive as they were for their time) found full expression in the voices. Though far from the first game to use voice acting, MGS featured one of the best implementations then seen in gaming, which – when combined with its diverse cast of interesting characters – went a long way toward pulling players into the story and making it feel as real and believable as Kojima wanted.

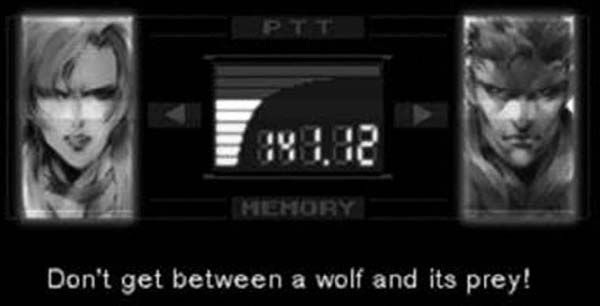

FIGURE 2.5

Snake’s radio support team is always ready to provide useful information and/or witty comments about the current situation.

Although it would still be a while before a large percentage of games adopted full or near-full voice acting (even on CDs, voice files required a very large amount of disc space), Metal Gear Solid set a standard for both the amount and quality of voice acting and brought about a change in the industry, showing that a character’s voice was just as important as his or her 3D model.

In the 2000s, successive generations of PCs and gaming consoles allowed drastic improvements in graphics, to the point of surpassing many of the best FMVs of past generations. At the same time, DVDs and Blu-ray discs have increased the amount of available storage space so that it’s no longer impractical for games to include hours of voice-overs and prerecorded music. With technological limitations fading rapidly, game designers and writers have begun to focus more heavily on improving their gameplay and stories while also experimenting with new and different types of games.

On PCs, FPS, real-time strategy (RTS), and simulation games retained their popularity but increasingly began adding stories and RPG elements to complement their traditional gameplay. Retaining the PC RPG genre’s strong focus on exploration and character development, many of these new games such as Fallout 3 (which we’ll talk about more in Chapter 10) and Borderlands strive to provide open-ended stories with expansive worlds and a large amount of freedom for players to explore and do as they please. Even more traditional FPS and RTS games, with linear campaigns and few if any RPG elements, frequently contain epic stories with well-developed characters, marking a significant change from the majority of earlier titles.

Traditional PC RPGs also continue to be made by companies like Bioware, though the genre is increasingly shifting online with MMORPGs (massively multiplayer online role-playing games) such as the immensely popular World of Warcraft. Most MMOs use a form of fully player-driven storytelling, though some have used open-ended and even interactive traditional stories as well (we’ll be talking in depth about MMOs and their storytelling styles in Chapter 11).

Of particular interest to longtime PC gamers, the point-and-click adventure game genre was revived almost single-handedly by Telltale Games. Staffed by many former LucasArts employees, Telltale brought back classic series such as Sam & Max and Monkey Island while also creating adventure games based on a variety of popular licenses.

While retaining the genre’s classic gameplay, tricky puzzles, and hilarious stories, Telltale’s games have updated the style with easier controls and inventory management, a discrete hint system (where characters will voice a suggestion as to what to do next when the player appears to be stuck), and a more robust and user-friendly conversation system. Another change that Telltale has brought to the genre is the concept of episodic games. Rather than release one big game every year or so, Telltale games are divided into seasons consisting of between four and six monthly “episodes” (games), each containing several hours of gameplay.

FIGURE 2.6

Sam and Max, freelance police, in their third season of episodic adventure games, Sam & Max: The Devil’s Playhouse.

FIGURE 2.7

Aliens, psychic powers, floating brains, and elder gods? Just another day on the job for Sam and Max.

This approach has allowed Telltale to release a steady stream of new games and also made it easy for gamers to try out a single episode for a low price before deciding whether they wish to buy the entire season. Depending on the particular season, the episodes can be anything from a series of self-contained though loosely connected adventures to chapters of a single full-length story. Though many companies have expressed interest in episodic games, Telltale is widely considered to be the only developer to get it right, and their hard work has introduced the PC adventure game genre to an entirely new generation of gamers.

Rapid growth also happened in the casual PC game market. Focusing on games that are simple to pick up and can be played easily in short sessions, many early casual games had little to no story, but as the genre has grown and matured, casual game developers have begun adding a wide variety of different stories (mostly using interactive traditional storytelling) to their games, such as Plants vs. Zombies and the Samantha Swift series of hidden picture games.

Another recent development in PC gaming is the sudden popularity of social networking games. Centered around social network sites such as Facebook, social networking games offer players a chance to work with (or sometimes against) their friends in a variety of different tasks. However, despite their meteoric rise to popularity, social networking games are still in their infancy and the majority of titles, such as the well-known FarmVille, focus primarily on attracting and retaining players with assorted mini-games and item collection systems, with little to no story to support the gameplay.

On consoles, the techniques that developed during the cinematic era have been expanded and refined, making game stories even more epic and filmlike in their presentations. As on PCs, RPG-style gameplay elements and stories have steadily spread to other genres, leading to the explosion of story-driven games of all types.

RPGs continue to be at the heart of game storytelling. Japanese RPGs such as FINAL FANTASY XIII and THE WORLD ENDS WITH YOU (which we’ll examine in depth shortly) still provide highly structured cinematic stories in many different styles and genres. In addition, ports of popular PC RPGs (such as The Elder Scrolls series and assorted Bioware games) along with a few specifically made for consoles (such as Fable 2, which we’ll discuss in Chapter 10) have given console gamers a taste of open-ended storytelling.

Meanwhile, a variety of action, adventure, platformer, and FPS games have been released that feature deep, well-done stories of their own. Interactive traditional storytelling still remains the dominant form, but multiple-ending, branching path, and open-ended storytelling have all been used in many games as well, creating a wide diversity of titles that are sure to contain something for every type of gamer.

A console development that has had surprising effect on game storytelling is the addition of online stores and downloadable games and content. The easy access to downloadable games has encouraged developers to release new and innovative titles such as Flower, which have experimented with many different types of gameplay and storytelling. It’s also allowed console gamers to experience some of the best casual and adventure games, which were formerly available only on PCs. At the same time, downloadable retro games have introduced many new gamers to now-classic titles such as FINAL FANTASY VII, Metal Gear Solid, and Ogre Battle, increasing interest in their stories, characters, and storytelling styles. This has also led to a trend of creating new retro-style games that make use of not only old-style graphics, music, and gameplay, but storytelling techniques as well.

Another change brought about by online stores is the concept of downloadable content (DLC). DLC is extra content released after a game has shipped that can be downloaded (often for a small fee) and added to an existing game. Though DLC usually comes in the form of new costumes, weapons, or playable characters, some companies have experimented with using DLC to expand a game’s story, including new areas, levels, and plot elements. Generally shorter and less expansive than the expansion packs familiar to PC gamers (which were frequently closer to complete sequels than simple add-ons), often costing several dollars and containing only a few hours at most of additional gameplay, DLC has been used in many games to expand on the setting and backstory (as in Grand Theft Auto IV and Heavy Rain) and/or to provide an epilogue to bridge the gap between a game and its sequel (as in Prince of Persia).

Perhaps the most important change in current game storytelling is the ongoing effort to integrate the story more tightly with the gameplay. In many older games, the storylines can feel rather tacked on, as if they were written after the game was already near completion and forced to fit into a preexisting level structure and gameplay style – which was, in fact, often the case. Though it’s still an ongoing process, more and more developers are realizing the importance of bringing writers in during the early planning and development stages to ensure that the story and gameplay are better matched. Developers are also experimenting with making tutorials and other fourth wall–breaking gameplay elements fit more naturally into the world. In Prince of Persia, for example, the player learns the basics of exploration and combat by following and mimicking the movements of a person he’s chasing, along with some unobtrusive text prompts, rather than having someone break character by telling the prince that he has to use the X button to jump. Other “gamey” elements – from health bars to healing potions – are also having their presence and functions modified or worked into the story, becoming less obtrusive in the process. Although many of these experiments have met with mixed success, they show the growing realizations throughout the industry that games are a strong storytelling medium and that it’s important to make an effort to fit the other elements of the game (gameplay, graphics, music, and so on) with the story rather than just forcing the story in at the last moment.

Case Study: THE WORLD ENDS WITH YOU

| Developer: | Square Enix Co., Ltd./Jupiter |

| Publisher: | Square Enix, Inc. |

| Writers: | Tatsuya Kando, Sachie Hirano, Yukari Ishida |

| System: | Nintendo DS |

| Release Date: | April 22, 2008 (US) |

| Genre: | Action RPG |

FIGURE 2.8

Neku and Shiki find themselves forced into a deadly game. © Square Enix Co., Ltd. All rights reserved.

When creating THE WORLD ENDS WITH YOU, the team set out to make a game that would take full advantage of the DS’s unique features – a goal at which they clearly succeeded. However, what really sets THE WORLD ENDS WITH YOU apart is the way it merges together its gameplay, graphics, music, and story into a single unified whole, with every single element of the game fitting with and supporting the others.

The game takes place in Tokyo’s trendy Shibuya district, the heart of Japanese fashion and teen culture. Featuring many fully recognizable streets and shops from the real Shibuya, THE WORLD ENDS WITH YOU uses its setting to exceptionally good effect. The sharp Japanese comic–style graphics fit and enhance both the setting and the focus on Japanese teen culture. The soundtrack – which is made up primarily of a fusion of musical influences from hip-hop to rock to electronica – does the same, providing the same type of listening experience you’d be likely to find in the stores of the real Shibuya. Character development is similarly setting appropriate. The characters’ stats are based primarily on their clothing, with new items being available for purchase from a wide variety of stores, all of which cater to fans of different Japanese fashion trends. Stats can also be permanently raised by eating at various restaurants and fast-food stands (in a realistic nod, characters can eat only so much every day before becoming full).

Store clerks start out impersonal and at times even rude, but grow more friendly and helpful as the player returns and continues to shop with them over the course of the game, offering special discounts, off-menu specials, and tips about various outfits’ secret abilities. Continuing the fashion theme, Neku’s attacks and special movies in battle are determined by which collectable pins he’s wearing. There are several hundred pins in the game, each with their own ability, and many are able to grow stronger and evolve into new and different pins as they’re used. Finally, depending on the day and particular part of Shibuya the player is in, different clothing and pin brands will be in and out of style. Tailoring your outfits to match the current fad will grant a nice stat boost in battle; wearing unpopular items will result in reduced stats, making for far more difficult fights. But, as any follower of fashion can tell you, fads are very prone to change. Showing your style by fighting while wearing a certain brand’s clothing will cause its popularity to slowly but surely rise, allowing determined players to work the trends to their own advantage. Though many of these elements may sound slightly gimmicky on their own, when combined, they go a long ways toward making the game’s virtual Shibuya feel almost as alive and dynamic as the real one.

The story begins when the teenage hero Neku wakes up in the middle of a crowded street with his memories a jumbled mess. Before he can figure out what’s going on, he’s attacked by a group of strange monsters. While trying to escape, he meets a girl named Shiki, who informs him that the monsters are called Noise and can be defeated only if the two of them form a pact and work together. As it turns out, Neku and Shiki are only one of many pairs being forced to compete in the Reaper’s Game. The Game challenges players to survive for seven days while completing a set of riddle-like missions (sent via cell phones, the one thing no Tokyo teenager goes without). If they’re defeated by the Noise or fail to complete any challenge within the allotted amount of time, they’ll be erased from existence. Neku, like many teenagers (in Japan or elsewhere), is a recluse who has trouble understanding other people and just wants to be left alone. As such, he isn’t at all happy about being forced into the Game or being teamed up with the upbeat and outgoing Shiki. However, as he is frequently reminded, one of the most important rules in the Game is to trust your partner.

FIGURE 2.9

Noise must be fought simultaneously on both screens of the DS. © Square Enix, Co., Ltd. All rights reserved.

The main reason necessitating this trust and the Game’s partner system is the Noise. Noise are monsters that exist simultaneously in two separate zones or planes of existence. The only way to defeat them is to fight them in both zones at once – hence the need for a partner. THE WORLD ENDS WITH YOU shows this by using a unique battle system in which the player uses the DS’s lower touchscreen to control Neku while simultaneously using the D-pad to control his partner on the top screen. Enemies exist on both screens and also disappear from both, regardless of which character finishes them off. Similarly, Neku and Shiki share a single life gauge, so ignoring one character in favor of the other generally results in a quick death. Though a bit difficult to master early on, the battle system is unique and extremely fun once the player gets used to fighting on two screens at once. It also strongly enforces the story theme of trusting and working with your partner. As the game progresses, and the player becomes more skilled at controlling both characters in battle (in essence, forming a stronger team bond between the two), Neku slowly begins to open up and trust Shiki as well, creating a perfect mirror between the character’s growth in the story and the player’s growth in the game.

Later on, a major plot twist forces Neku to team up with a new partner, Joshua. Unlike Shiki, who was relatively easy to like, Joshua acts smugly superior and seems to be up to something behind Neku’s back. As much as Neku knows that he needs to trust Joshua, his personality makes it very difficult to do so. These mixed feelings are mirrored on the gameplay side. In battle, Joshua plays much differently than Shiki, completely throwing off whatever rhythm the player had established during the first part of the game. Once again, however, as time passes, the player will grow used to Joshua’s fighting style and come to appreciate his skills, much as Neku and Joshua start to put aside their differences and become friends.

FIGURE 2.10

Tokyo’s vibrant Shibuya district is expertly re-created. © Square Enix, Co., Ltd. All rights reserved.

Neku and his friends’ growth is conveyed in other ways as well. Though contestants in the Game can’t interact directly with most of Shibuya’s residents, they’re given the ability to read their minds. Aside from being very useful on certain missions, it also helps to show Neku that other people aren’t really so hard to understand and have their own problems and uncertainties, just like he does.

Another concept that plays a large role in the story and gameplay, aside from trust and friendship, is that of bravery. It requires a certain amount of bravery to trust and open up to others – and the more dark or embarrassing some part of your past or personality is, the more bravery is required to share it. Neku’s growing bravery can be clearly seen throughout the story, but like the rest of THE WORLD ENDS WITH YOU’s elements, it’s mirrored in the gameplay. I already talked about how clothing and fashion play a role in the game; if you’re at all familiar with Japanese fashion, you won’t be surprised to know that some of the available outfits are extremely over the top. The interesting thing about the clothing in THE WORLD ENDS WITH YOU is that, with a few exceptions, any character can equip any item. If you want to put Neku in a frilly pink dress and combat boots with a skateboard and a stuffed cat, you can do it … provided that he’s brave enough to pull it off. Each piece of clothing has a minimum bravery rating required to wear it. A T-shirt or pair of slacks isn’t a big deal; a maid outfit can only be worn by the truly brave. As with other stats, the characters’ bravery can be raised throughout the course of the game, but gradually, just as their bravery slowly increases in the story. Bravery is also demonstrated during battles, which feature a strong risk vs. reward factor. When fighting, players can choose to chain a large number of battles back to back, without a chance to rest or heal in between. Though risky, it significantly increases the chance that enemies will drop money or pins. The player can also choose to increase the game’s difficulty, allowing him or her a chance at receiving rarer items, and/or fight at a significantly reduced level, which will provide an additional boost to enemy drop rates. Early in the game, fighting with a high difficulty setting, reduced level, or in a long chain is likely to result in a “game over” screen, but as the game progresses and the player grows more confident with the battle system and more trusting of Neku’s partner, he or she will become braver and will end up fighting long chains of high difficulty battles at a reduced level in order to claim the best prizes.

In the end, THE WORLD ENDS WITH YOU succeeds on many levels with its stylish graphics, catchy soundtrack, deep enjoyable battle system, and engaging story. But it’s the way these elements combine while strengthening and complementing each other that makes the game far more than the sum of its parts.

The Limits of Storytelling in Games

With the memory and processing power of modern computers and game consoles, there’s no type of story that can’t be told in games. Some types of stories don’t lend themselves as easily to games as others (something we’ll talk about more in Chapter 3), but with enough planning and creativity, there’s no reason stories in any genre or style can’t be made into good games. Games even allow for stories that give the player a significant amount of freedom and control over the progression and outcome of the main plot. However, it’s when working with high levels of player control and interactivity that we encounter the limits of game storytelling.

The most important thing to realize is that in any game, the player can do only things that the designers, programmers, writers, and other creators accounted for when crafting the game. Similarly, the game can respond to the player only in a set of predetermined ways. Though artificial intelligence (AI) can be used to allow computer-controlled enemies and allies some semblance of thought and planning, any gamer will be quick to point out that even the best AI-controlled enemies and allies can’t compare to having a good human at the controls. And that’s just one of the simpler forms of AI.

Let’s say there’s a game using a very open and nonlinear form of storytelling and the hero is sitting at a table talking to a rather dodgy individual. In this game, the hero may have a choice between several different things to say (let’s suppose there’s a threatening response, a friendly response, and a clever response) along with the ability to bribe the other man, kill him, or get up and leave. That seems like a lot of options. But what if the same situation were occurring in real life? The hero would have all of those options, but there’d be many other things he could do as well. He could offer to work for the other man, talk about the weather, jump up on the table and dance a waltz, or do any of a limitless number of other things. Many of the actions he could take would be pointless, impractical, or even utterly ridiculous, but that doesn’t change the fact that he could do them if he wanted to. But in games, no matter how much freedom players are given, if the design team didn’t put in a dance option, the player can’t dance, and if they didn’t give him the option to talk about the weather, he’ll be unable to do so. A real-life hero could even decide to ignore his quest entirely, go home, and watch TV. But unless the art team created a model for the hero’s home and also made a whole bunch of TV shows for him to watch, that isn’t going to happen either.

To put it bluntly, with the infinite number of choices present in real life, there’s no way even the best and largest game company could ever hope to account for them all. At present, the only way such a thing is possible is to have a human moderator (like a dungeon master in a game of Dungeons & Dragons) who listens to the player’s actions and then twists, changes, and even completely rewrites the story as he or she goes. And although that works fine for a few friends sitting at a kitchen table using their imagination, it’s obviously impossible to do in a game played by millions of people where a single area or character can take weeks or even months of work to create. The only other option would be to create a computer AI whose knowledge, understanding, and creativity are close enough to those of the human brain that it would be capable of acting as a dungeon master, writing new story sections and creating new game areas and elements on the fly to suit the players’ actions.

If you were to ask a collection of computer programmers and tech experts how far away we are from creating such an AI, you’ll get answers ranging from a couple of years to a couple of centuries; some will say that it’s utterly impossible, no matter how much time is involved. My own personal opinion is that if such an AI can be created, it’s most likely decades or even centuries away. However, there’s really no way of knowing other than to wait and see what happens. If a fully competent dungeon master AI ever is created, it would drastically change the face of gaming and game writing, but at this point in time, there’s little use worrying about how to use or work with a technology that’s so far from completion. If and when the time comes, such an AI would probably work far differently than we can imagine today, so there’s little reason to speculate. A more interesting question is whether giving players total freedom to do as they please in games would really be a good idea, but that’s a debate for later on.

The Rubber Meets the Road

One of the hidden challenges of creating interactive stories is the realities of game production and the limitations imposed upon writers. I’ve been in many meetings in which the publishers wanted widely branching stories – the kind that allow (and encourage) multiple replays of the game. They adored the idea of adding a bullet point to the back of the box stating “infinitely replayable!” And so did we, the writers. However, the reality of production was our enemy. It has been my industry experience that the single most expensive part of game production is content. By “content,” I mean creating the environments, characters, levels, dialog, artwork, and animations in which the player experiences the game, which takes more time and manpower than any other single element of the game, including the software coding. Most inexperienced people looking at games don’t fully grasp how cost- and time-intensive these parts are. And, when cost containment begins to enter the discussions, you can often get a great deal of bang for your buck when you begin to talk about cutting story lines, characters, levels, and so on. After all, it’s not just the creation of the assets that costs money. The testing, polishing, and debugging of these play areas often cost as much or more than building the assets in the first place.

Because of this, the same people in management who were understandably advocates for multiple branching storylines are first in line to suggest “corraling” the breadth of the game’s story possibilities in order to contain costs – especially when it might be mentioned that players may not see all the content when the play the game. If you originally designed, say, four endings, it may be obvious to you that upon playing the game the first time, only one of those endings can be enjoyed by the player. The other three will be seen only if the player completes the game four times. When management is looking to cut costs, spending money on content that may or may not be seen by the typical player is not viewed favorably.

The dirty secret here is that few gamers (few as compared to the number of copies sold of any title) actually complete a game once, let alone multiple times. So it’s often hard to justify the cost and development time for many multiple endings, middles, and beginnings.

I was sitting in a room the other day with a half-dozen gamers, all of whom had played Dragon Age: Origins. They were discussing the four main multiple endings amongst themselves as I listened. All these players were big fans. None of them had played the game more than once, even though all of them had played it to completion. When I asked them about the lure of multiple endings, they talked about how cool it was that there were multiple endings, but none of them was intrigued enough to play the game again to see how the alternate path felt, as the game had been satisfying enough once through.

Was it worth the money to create the multiple endings? Only EA knows for sure.

—Chris

Although games and game stories originally faced serious technical limitations, these limitations have all but disappeared over the past several decades, allowing game designers and writers to create nearly any type of game and story that they can imagine. This freedom has also given rise to a lot of experimentation with new and different storytelling techniques. One especially popular trend is to give players more control with branching path, open-ended, and fully player-driven stories (all of which will be explained in depth in Chapters 6 through 11), though there’s a limit as to how much freedom they can allow. However, interactive traditional stories continue to dominate the market (as shown in Chapter 14).

The importance of creating games with good stories is also being realized. Once found only in RPGs and adventure games, deep and twisting plots and well-defined characters are now present in games in all genres. The diversity of game and story types means that now, more than ever, there are games that will satisfy any type of player. Perhaps most importantly, game developers are working harder to ensure that all the different parts of their games work together with and support the story, creating far more cohesive and engaging experiences.

1. What do you consider to be several of the most important and influential games in the history of game storytelling and why?

2. Do you think voice-overs and FMVs significantly improve the way games tell their stories? Why or why not?

3. In what ways do you believe that game storytelling has improved over the last five years? How about the last ten years?

4. Are there any particular aspects of game storytelling that you think still need significant improvement? What are they and how could they be improved?

5. Do you believe that a dungeon master AI would improve game storytelling? Why or why not?