IN THIS CHAPTER

Examining image file formats

Working with foreground and background images

Inserting images from the Assets panel

Dreamweaver Technique: Including Images

Revising graphics

Dreamweaver Technique: Changing Graphics

Modifying image height, width, and margins

Aligning and wrapping text around images

Dividing your page with HTML lines

Putting graphics into motion

Adding rollovers

Inserting navigational buttons

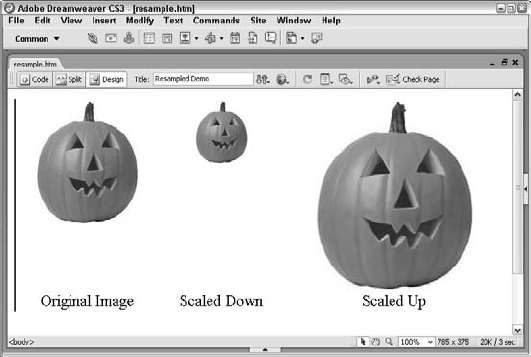

The Internet started as a text-based medium primarily used for sharing data among research scientists and among U.S. military commanders. Before long, however, the Web became as visually appealing as any mass medium. Dreamweaver's power becomes even more apparent as you use its visual layout tools to incorporate background and foreground images in your Web page designs.

This chapter opens with an overview of the key Web-oriented graphics formats, including PNG. This chapter also covers techniques for incorporating both background and foreground images—and modifying them using the methods available in Dreamweaver. You also learn about animation graphics and how you can use them in your Web pages, plus techniques for creating rollover buttons and navigation bars.

If you've worked in the computer graphics field, you know that virtually every platform—as well as every paint and graphics program—has its own proprietary file format for images. One of the critical factors driving the Web's rapid, expansive growth is the use of cross-platform graphics. Regardless of the system you use to create your images, these versatile files ensure that the graphics can be viewed by all platforms.

The trade-off for universal acceptance of image files is a restricted field: just two primary file formats, with a third just now coming into view. Currently, only GIF and JPEG formats are fully supported by browsers. A third alternative, the PNG graphics format, has experienced a growing acceptance and, with the release of Internet Explorer 7, may have finally arrived.

You need to understand the uses and limitations of these formats to apply them successfully in Dreamweaver. The following sections look at the fundamentals.

The Graphics Interchange Format (GIF) was developed by CompuServe in the late 1980s to address the problem of cross-platform compatibility. With GIF viewers available for every system from PC and Macintosh to Amiga and NeXT, the GIF format became a natural choice for an inline (adjacent to text) image graphic. GIFs are bitmapped images, which means that each pixel is given or mapped to a specific color. You can have up to 256 colors for a GIF graphic. These images are generally used for line drawings, images of text, logos, or cartoons—anything that doesn't require thousands of colors for a smooth color blend, such as a photograph. With a proper graphics tool like Adobe Fireworks, you can reduce the number of colors in a GIF image to a minimum, thereby compressing the file and reducing download time.

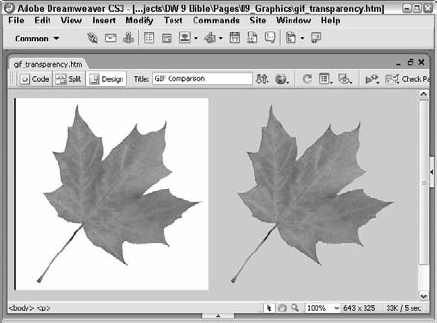

The GIF format has two varieties: regular (technically, GIF87a) and an enhanced version known as GIF89a. This improved GIF file brings three important attributes to the format. First, GIF89a supports transparency, whereby one or more colors can be set to automatically match the background color of the page containing the image. This property is necessary for creating nonrectangular-appearing images. Whenever you see a round or irregularly shaped logo or illustration on the Web, a rectangular frame is displayed as the image is loading—this is the actual size and shape of the graphic. The colors surrounding the irregularly shaped central image are set to transparent in a graphics-editing program (such as Adobe Fireworks or Adobe Photoshop) before the image is saved in GIF89a format.

Note

Most of the latest versions of the popular graphic tools default to using GIF89a, so unless you're working with older, legacy images, you're not too likely to encounter the less flexible GIF87a format.

Although the outer area of a graphic seems to disappear with GIF89a, you won't be able to overlap your Web images using this format without using AP elements. Figure 9-1 demonstrates this situation. In this figure, the same image is presented twice—one lacks transparency, and one has transparency applied. The image on the left is saved as a standard GIF without transparency, and you can plainly see the shape of the full image. The image on the right was saved with the white background color made transparent, but while the central figure seems to float on the background, its full shape is still there.

Figure 9-1. The same image, saved without GIF transparency (left) and with GIF transparency (right).

The second valuable attribute contributed by GIF89a format is interlacing. One of the most common complaints about graphics on the Web is lengthy download times. Interlacing won't speed up your GIF downloads, but it gives your Web page visitors something to view other than a blank screen. A graphic saved with the interlacing feature turned on gives the appearance of developing, like an instant picture, as the file is downloading. Use of this design option is up to you and your clients. Some folks swear by it; others can't abide it.

Animation is the final advantage offered by the GIF89a format. Certain software programs enable you to group your GIF files together into one large page-flipping file. With this capability, you can bring simple animation to your page without additional plugins or helper applications. Unfortunately, the trade-off is that the files get very big, very fast. For more information about animated GIFs in Dreamweaver, see the section "Applying Simple Web Animation" later in this chapter.

The JPEG format was developed by the Joint Photographic Experts Group specifically to handle photographic images. JPEGs offer millions of colors at 24 bits of color information available per pixel, as opposed to the GIF format's 256 colors and 8 bits. To make JPEGs usable, the large amount of color information must be compressed, which is accomplished by removing what the compression algorithm considers redundant information.

Note

JPEG files can be named with a file extension of .jpg, .jpeg, or .jpe. However, the most commonly used extension is .jpg.

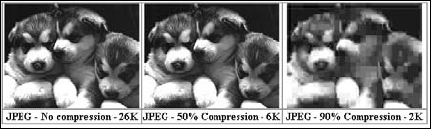

The more compressed your JPEG file, the more degraded the image. When you first save a JPEG image, your graphics program asks you for the desired level of compression. For example, consider the three images shown in Figure 9-2 and compare the effects of JPEG compression ratios and resulting file sizes to the original image itself. Note, however, that results vary depending on the image. As you can probably tell, JPEG does an excellent job of compression so that even a substantial degree of compression has only minimal visible impact. Keep in mind that every graphic has its own reaction to compression.

Figure 9-2. JPEG compression can save your Web visitors significant download time with little loss of image quality.

Note

With the JPEG image-compression algorithm, the initial elements removed from a compressed image are the least noticeable. Subtle variations in brightness and hue are the first to disappear. When possible, preview your image in your graphics program while adjusting the compression level to observe the changes. With additional compression, the image grows darker and less varied in its color range.

If you use Fireworks as your graphics editor, you can optimize image file size without leaving Dreamweaver. See Chapter 24 to learn more.

With JPEGs, what is compressed for storage must be uncompressed for viewing. When a visitor's browser accesses a JPEG picture on your Web page, the image must first be downloaded to the browser and then uncompressed before it can be viewed. This dual process adds additional time to the Web-browsing process, but it is time well spent for photographic images.

Unlike GIFs, JPEGs have neither transparency nor animation features. A newer strand of JPEG called Progressive JPEG gives you the interlacing option of the GIF format, however. Although not all browsers support the interlacing feature of Progressive JPEG, they render the image regardless.

The latest entry into the Web graphics arena is the Portable Network Graphics format, or PNG. Combining the best of both worlds, PNG has lossless compression—meaning no pixels are lost when the file is compressed—like GIF, and is capable of rendering millions of colors, like JPEG. Moreover, PNG offers an interlacing scheme that appears much more quickly than either GIF or JPEG, as well as superior transparency support.

One valuable aspect of the PNG format enables the display of PNG pictures to appear more uniform across various computer platforms. Generally, graphics made on a PC look brighter on a Macintosh, and Mac-made images seem darker on a PC. PNG includes gamma correction capabilities that alter the image depending on the computer used by the viewer.

Before the 4.0 versions, the various browsers supported PNG only through plugins. After PNG was endorsed as a new Web graphics format by the W3C, both 4.0 versions of Netscape and Microsoft browsers added native, inline support of the new format for Windows and full PNG support is finally available in Internet Explorer 7. On Macs, PNG format is supported in Internet Explorer 5.2, Safari 1.0 and above, as well as Netscape 6 and above; Netscape 4.x browsers still require the plugin. Perhaps most important, however, Dreamweaver was among the first Web-authoring tools to offer native PNG support. Inserted PNG images are previewed in the Document window just like GIFs and JPEGs. Both Adobe Photoshop and Adobe Fireworks can export graphics in PNG format.

Note

Fireworks actually outputs two different types of PNG graphics. The Fireworks source file uses an extended PNG format, which allows graphics, effects, and text to remain editable; however, it also causes the images to be substantially larger in file size. To use a PNG file from Fireworks, make sure you actually export it as a PNG file.

An inline image can appear directly next to text—literally in the same line. The capability to render inline images is one of the major innovations in the evolution of the World Wide Web. This section covers all the basics of inserting inline images and modifying their attributes using Dreamweaver.

You can open and preview any graphic in a GIF, JPEG, or PNG format in Dreamweaver. You have many options for placing a graphic on your Web page:

Position your cursor in the document, and from the Common category of the Insert bar, click the Image button.

Position your cursor in the document, and from the menu bar, choose Insert

Position your cursor in the document and press Ctrl+Alt+I (Command+Option+I).

Drag the Image button from the Images menu of the Insert bar's Common category onto your page.

Drag an icon from your file manager (Explorer on Windows or from the Finder or the Desktop on a Mac) or from the Files panel onto your page.

Drag a thumbnail or filename from the Image category of the Assets panel onto your page. This capability is covered in detail in a subsequent section, "Dragging Images from the Assets Panel."

For all methods except those using the Assets panel or the file manager, Dreamweaver opens the Select Image Source dialog box (shown in Figure 9-3) and asks you for the path or address to your image file. Remember that in HTML, all graphics are stored in separate files linked from your Web page.

Figure 9-3. In the Select Image Source dialog box, you can keep track of your image's location relative to your current Web page.

Note

Dreamweaver's Select Image Source dialog box includes two main options at the top: Select File Name From File System or From Data Sources. This chapter covers inserting static images from the file system. For information about including dynamic images from data sources, see Chapter 20.

Whether you are choosing from the file system or a data source, the image's address can be a filename, a directory path and filename on your system, a directory path and filename on your remote system, or a full URL to a graphic on a completely separate Web server. The file doesn't need to be immediately available for the code to be inserted into your HTML.

Tip

If you have an always-on Internet connection such as cable or DSL, Dreamweaver displays images referenced by absolute URLs right in Design view. Dreamweaver automatically reads and includes the width and height dimensions in the generated source code.

From the Select Image Source dialog box, you can browse to your image folder and preview images before you load them. If you are using Mac OS X, the image preview is automatically enabled. On Windows, select the Preview Images option.

In the lower portion of the dialog box, the URL text box displays the format of the address that Dreamweaver inserts into your code. Below the URL text box is the Relative To list box. Use it to declare an image relative to the document you're working on (the default) or relative to the site root. (After you've saved your document, you can see its name displayed beside the Relative To list box.)

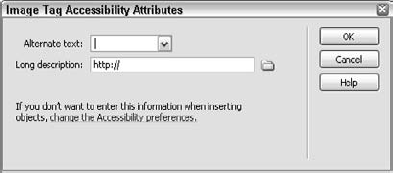

When you insert an image, you may also see the Image Tag Accessibility Attributes dialog box, depending on your preference settings. See the section "Adding Image Descriptions" for more information about this dialog box.

Note

To take full advantage of Dreamweaver's site management features, you must open a site, establish a local site root, and save the current Web page before beginning to insert images. For more information about how to begin a Dreamweaver project, see Chapter 5.

After you've saved your Web page and chosen Relative to Document, Dreamweaver displays the address in the URL text box. If the image is located in a folder on the same level as or within your current site root folder, the address is formatted with just a path and filename. For instance, if you're inserting a graphic from the subfolder named Images, Dreamweaver inserts an address like the following:

images/logo.jpg

If you try to insert an image currently stored outside of the local site root folder, Dreamweaver automatically copies the image file to your Default Images Folder, specified when you first created the site.

Note

To change the setting for your Default Images Folder, choose Site

If your site does not include a Default Images Folder, you see the prompt window shown in Figure 9-4, asking if you want to copy the image to your local site root folder. If you click Yes, Dreamweaver gives you an opportunity to specify where the image should be saved within the local site. Whenever possible, keep all your images within the local site root folder so that Dreamweaver can handle site management efficiently.

Figure 9-4. Dreamweaver reminds you to keep all your graphics within the local site root folder for easy site management.

If you attempt to drag an out-of-site image file from the Files panel or from your file manager, and you click No to the prompt asking to copy the file to your site, the file is not inserted. If you attempt to insert the file using the Select Image Source dialog box and answer No, the file is inserted with the src attribute pointing to the path of the file. In this case, Dreamweaver appends a prefix that tells the browser to look on your local system for the file. For instance, the file listing looks like the following in Windows:

file:///C|/Dreamweaver/images/logo.jpg

whereas on the Macintosh, the same file is listed as follows:

file:///Macintosh HD/Dreamweaver/images/logo.jpg

Warning

If you upload Web pages with this file:///C| (file:///Macintosh HD) prefix in place, the links to your images are broken. It is easy to miss this error during your testing. Because your local browser can find the referenced image on your system, even when you are browsing the remote site, the Web page appears perfect. However, anyone else browsing your Web site sees only placeholders for broken links. To avoid this error, always save your images within your local site.

Dreamweaver also appends the file:///C| prefix (or file:///Macintosh HD in Macintosh) if you haven't yet saved the document in which you are inserting the image. However, when you save the document, Dreamweaver automatically updates the image addresses to be document-relative.

If you select Site Root in the Relative To field of the Select Image Source dialog box and you are within your site root folder, Dreamweaver appends a leading forward slash to the directory in the path. The addition of this slash enables the browser to correctly read the address. Thus, the same logo.jpg file appears in both the URL text box and the HTML code as follows:

/images/logo.jpg

When you use site-root–relative addressing and you select a file outside of the site root, the image file is automatically copied to your Default Images Folder, if one exists. If your site does not have a Default Images Folder, you get a reminder from Dreamweaver about copying the file into your local site root folder—just as with document-relative addressing.

Note

For more details about using dynamic sources for your images, see Chapter 20.

Web designers often work from a collection of images, much as a painter uses a palette of colors. Reusing images builds consistency in the site, making it easier for a visitor to navigate through it. However, trying to remember the differences between two versions of a logo—one named logo03.gif and another named logo03b.gif—used to require inserting them both to find the desired image. Dreamweaver eliminates the visual guesswork and simplifies the reuse of graphics with the Assets panel.

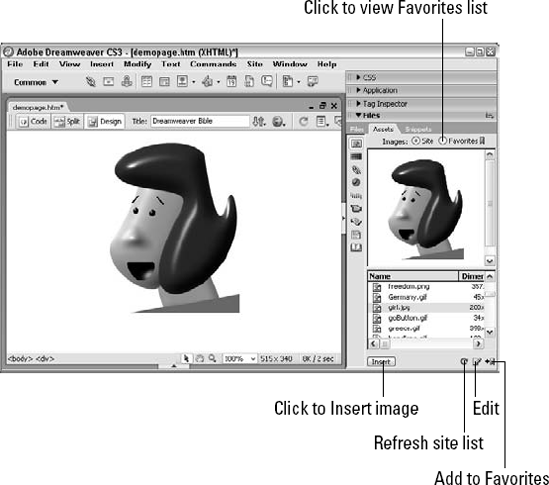

The Images category is key to the Assets panel. Not only does the Assets panel list all the GIF, JPEG, and PNG files found in your site—whether or not they are embedded in a Web page—selecting any graphic from the list instantly displays a thumbnail. Previewing the images makes it easy to select the proper one, and then all you need to do is drag it from the Assets panel onto the page.

Before you can use graphics from the Assets panel, you must inventory the site by choosing the Refresh Site List button, as shown in Figure 9-5. When you click the Refresh button (or choose Refresh Site List from the context menu on the Assets panel), Dreamweaver examines the current site and creates a list of the graphics, including their sizes, file types, and full paths. To see an image, just click its name, and a thumbnail appears in the preview area of the panel.

Tip

To increase the size of the thumbnail, make the preview area larger by dragging open the border between the preview and list areas and/or increasing the size of the entire panel. Dreamweaver enlarges the size of the thumbnail while maintaining the width:height ratio, so if you just move the border or resize the panel a little bit, you may not see a significant change. Thumbnails are never displayed larger than their actual size.

You can insert an image from the Assets panel onto your Web page in two ways:

Drag the image or the file listing onto the page.

Place your cursor where you'd like the image to appear. Select the image in the Assets panel and then click the Insert button.

Figure 9-5. Reuse any graphic in your site or from your Favorites collection by dragging it from the Assets panel.

Warning

Do not double-click the image or listing in the Assets panel to insert it onto the page; double-clicking invokes the designated graphics editor, be it Adobe Fireworks, Adobe Photoshop, or another program, and opens that graphic for editing. From the Document window, Ctrl+double-clicking (Command+double-clicking) accomplishes the same thing.

The Dreamweaver Assets panel is designed to help you work efficiently with sites that contain many images. For example, in large sites, it's often difficult to scroll through all the graphics filenames looking for a particular image. To aid your search, Dreamweaver enables you to sort the Images category by any of the columns displayed in the Assets panel: Name, Size, Type, or Full Path. Clicking the column heading once sorts the assets in an ascending order by that criterion; click the column heading again to sort by that same criterion in a descending order.

You can also use the Favorites list to separately display your most frequently used images, giving you quicker access to them. To add an image to the Favorites list, select the image in the Assets panel, and then click the Add to Favorites button or select Add to Favorites from the Assets panel context menu. To retrieve an image from Favorites, first select the Favorites option at the top of the Assets panel. To switch back to the current site, choose the Site option.

Dreamweaver makes it easy to organize your favorite images by enabling you to create folders in the Favorites list. To create a folder, click the New Favorites Folder button in the Assets panel with the Favorites list displayed. Add images to the folder by dragging the image names in the Favorites list to the folder.

Note

Moving an image to a folder in your Favorites list does not change the physical location of the image file in your site. You can organize your Favorites list however you choose without disrupting the organization of files in your site.

If one or more objects are selected on the page, the inserted image is placed after the selection; Dreamweaver does not permit you to replace a selected image with another from the Assets panel. To change one image into another, double-click the graphic on the page to display the Select Image Source dialog box.

One final point about adding images from the Assets panel: If you reference a graphic from a location outside of the site, Dreamweaver asks that you copy the file from its current location. You must click the Refresh Site Files button to display this new image in the Assets panel.

Tip

When you click the Refresh button, Dreamweaver adds new images (and other assets) to the cache of current assets. If you add assets from outside of Dreamweaver—using, for example, a file manager—you might need to completely reload the Assets panel by Ctrl+clicking (Command+clicking) the Refresh button, or by selecting Recreate Site List from the Assets panel context menu.

It's the rare graphic that integrates into the Web page design unaltered. Digital photographs often need to be cropped and almost always need to be reduced—either in dimensions, file size, or both. Other images may need to be sharpened to achieve an immediate effect or lightened to fit better into the page palette. Dreamweaver provides several pathways to the perfect Web image:

Image editing within Dreamweaver: Without even leaving Dreamweaver, you can crop, resample, sharpen, and alter brightness and contrast of any selected GIF or JPG graphic. You don't even have to have a graphics editor such as Adobe Fireworks installed. You'll see how shortly.

Graphic optimization through Fireworks within Dreamweaver: For more sophisticated image operations—without full-scale editing—choose Optimize Image. A Fireworks-derived dialog box opens within Dreamweaver where you can compare different outcomes before committing to a scaling, resampling, or conversion operation. You'll explore this option a little later in the "Employing the Optimize Image Command" section.

Round-trip editing from Dreamweaver to your graphics editor: For the most complex image modifications, use an external graphics editor such as Adobe Photoshop or Fireworks. Dreamweaver sends files to the editor of your choosing.

The route you take depends on the depth of the modifications required. A key difference among these three different types of operations (one that you'll want to factor into your image-editing decision) is that the tools within Dreamweaver work on the actual graphic exported for Web use. After the page containing the image is saved, changes cannot be reversed. If Fireworks is your graphics editor, both the Optimize and Graphics Editor options can utilize the source files and create the exported file. The main advantage to using source graphics is that you have much greater control and flexibility; many types of changes can be done and undone as many times as needed. The primary disadvantage is that not all Web designers have the option to alter the source graphics.

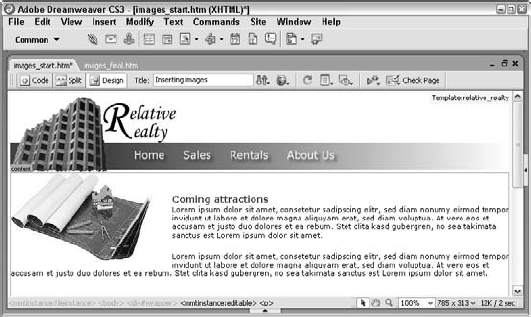

Regardless of which route you choose, you'll find it's easy to get there. Dreamweaver has centralized access to all of the graphic tools in the most appropriate place—the Image Property inspector (see Figure 9-6).

Begin your tour of Dreamweaver image altering options by looking at the built-in tools first.

If you want to show only part of photograph in the real world, you'd use a pair of scissors to crop off what you don't want. With digital graphic tools, no scissors are needed. Images are cropped for two main reasons: to focus attention on a particular area or to reduce file size. Often these reasons work hand-in-glove because a cropped image is always smaller than the original in both physical dimensions and file size.

Dreamweaver's cropping tool is both powerful and easy to use. When you choose to crop a graphic, a shaded border appears within the graphic. The edges of the border can be dragged to determine how the image should be trimmed. The region outside the border is darkened, but you can still see the full image so you can be sure a vital part of the graphic is not inadvertently cut.

To crop an image, follow these steps:

Select the image you want to crop.

In the Property inspector, click the Crop button.

Dreamweaver displays an alert to warn you that the cropping operation changes the selected image; click OK to clear the dialog. A shaded border appears within the selected image (see Figure 9-7).

Drag the selection handles that appear in the middle of each side to crop the image in a single direction; the cursor changes to a two-headed arrow when in the correct position to crop a side.

To move the entire cropping area, drag the highlighted rectangle into the desired position; you can move the cropping area when the cursor is shown as a four-headed arrow.

To cancel the cropping operation, click anywhere outside the graphic.

Complete the crop by double-clicking within the image.

After cropping, you can reverse the effect by choosing Edit

Finding the perfect size for an image is often a matter of trial-and-error: It's important that a graphic work together with the entire page layout for maximum effect. Dreamweaver makes it easy to resize an image—just drag the sizing handles to the desired location. (You can find a complete discussion of Dreamweaver's resizing features later in this chapter in the "Adjusting Height and Width" section.) However, resizing an image in Dreamweaver is not the same as rescaling it in a graphics program; Dreamweaver merely draws the image to fit the chosen dimensions, much as a browser would. It doesn't actually re-create the graphic.

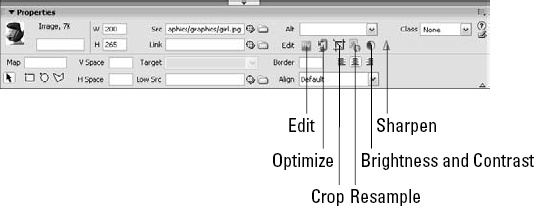

To get the cleanest, clearest representation of a resized graphic, you must resample the image. Resampling refers to the process of adding or subtracting pixels when the image is resized. If a graphic's dimensions are increased, pixels are formulaically added; make the image small and pixels are removed according to a similar algorithm. Dreamweaver includes a resampling option, which becomes available when an image is resized, either by dragging the sizing handles or changing the values in the Width and Height fields of the Property inspector.

Resampling in Dreamweaver is a one-click affair—no parameters are set. Just choose the resized image and click the Resample button on the Property inspector. As with the other built-in tools, an alert informs you that the graphics file is being changed (unless you've selected the Don't Show Me This Message Again option).

How the image resamples really depends on the image itself and the difference between the original image size and the new size. Sometimes, resampling in either direction results in satisfactory images (see Figure 9-8). Typically, I find that small differences work far better than large ones; if you're making a major change in image size, it's often better to use a dedicated graphics editor such as Fireworks or Photoshop.

Digital photography has opened the floodgates for posting images on the Web. Unfortunately, not all images look as good as they might. If you want to make the graphic lighter or darker or perhaps use a little more contrast, Dreamweaver has just the tool you need. The Brightness and Contrast command offers independent control over the two interlinked aspects of an image. Best of all, the Brightness/Contrast dialog box offers a Preview option, as shown in Figure 9-9, so that you can see the changes to the image in real time.

Figure 9-9. Preview the changes when using the Brightness and Contrast control to make sure you're getting the effect you want.

To alter the brightness and/or contrast of an image, follow these steps:

Select the image you want to modify.

Click the Brightness and Contrast button on the Property inspector. Dreamweaver displays the Brightness/Contrast dialog box.

Make sure the Preview box is selected to see the changes applied as you move the controls.

Drag the Brightness slider to the left or right; dragging the slider to the left lowers the brightness; dragging it to the right increases brightness. Alternatively, you can enter a value directly in the Brightness field. Acceptable values are from −100 to 100, with 0 being the default.

Move the Contrast slider to the right to increase the contrast or to the left to decrease it. Alternatively, you can enter a value between −100 and 100 in the Contrast field.

When you're finished, click OK.

Although Brightness and Contrast is most frequently associated with photographic JPG images, it can also be used for GIFs. However, be careful if your GIF has a transparent area; altering the brightness and/or contrast too much could make the transparent area visible.

In Web applications, fuzzy logic is generally sought after, but fuzzy photos are not. You can clear up blurry images with Dreamweaver's Sharpen command found on the Property inspector.

The Sharpen command examines the edges found within a graphic and programmatically increases the contrast of the related pixels. Flat areas of color are left unaffected. The Sharpen dialog (see Figure 9-10) offers a sliding scale from 0 to 10 where 10 represents the maximum amount of sharpening available in one operation. As with the Brightness/Contrast dialog, you can select the preview option.

Note

If you're using Fireworks and need more sharpening power than Dreamweaver offers, try applying the Unsharp Mask in Fireworks. Despite the name, this filter is terrific for sharpening blurry images and, when applied as a Live Filter from the Property inspector, is totally reversible in a Fireworks native PNG file.

Not all images are Web-ready—especially those that are used in other media such as printing. To provide the best online experience, Web graphics must balance appearance and file size. You want your images to look as good as possible at the lowest possible file size because a small file is quicker to download. The process of achieving the balance between the image quality and file size is called optimizing. You can optimize your images without leaving Dreamweaver by running the Optimize command.

Note

Unlike previous versions of Dreamweaver, you no longer need Fireworks installed to run the Optimize feature.

The Optimize command actually opens a dialog box that originated in Fireworks as the Image Preview dialog. Exporting from Fireworks is a major step and a lot of options are at your fingertips during the process. Here's just a little of what's possible:

Switch formats from GIF to JPEG or vice versa. Other formats include animated GIF and PNG.

Alter the palette depth (the number of colors) or transparency in GIF images.

Change the JPEG compression quality.

Rescale an image by an exact percentage or to a specific width or height.

Crop a figure visually.

Control the frame rate for animated GIF as well as the looping options.

Visually compare up to four different optimized images at the same time (see Figure 9-11).

When you first launch Optimize Image—either by clicking the Optimize button on the Property inspector or choosing the Optimize Image command from the Commands menu—Dreamweaver presents a dialog that asks whether you'd like to edit the source PNG file or the current file. When you choose the source file, Dreamweaver automatically re-exports the file and stores the changes when you're done.

Note

For a full explanation of all that's possible through the Optimize Image command, see Chapter 24.

Although Dreamweaver includes some tools for cropping, sharpening, and otherwise revising images in your Web pages, it is not a full-featured graphics editor. Certain tasks—such as slicing a larger graphic into sections or adding text to an image—are beyond Dreamweaver's scope. You can, however, set up your graphics editor of choice to work hand-in-hand with Dreamweaver. Specify your primary graphics editor for each type of graphic in the File Types/Editors category of Preferences.

After you've picked an image editor, clicking the Edit button in the Property inspector opens the application with the current image. After you've made the modifications, just save the file in your image editor and switch back to Dreamweaver. The new, modified graphic has already been included in the Web page. If you change the image size, you can click the Reset Size button on the Image Property inspector to see your changes.

Note

If you are using either Photoshop or Fireworks as your image editor, here is some good news: Dreamweaver works very closely with both Photoshop and Fireworks, enabling you to create and modify images with round-trip ease. Find out more in Chapter 24.

When you insert an image in Dreamweaver, the image tag, <img>, is inserted into your HTML code. The <img> tag takes several attributes; the most commonly used can be entered through the Property inspector. Code for a basic image looks like the following:

<img src="images/myimage.gif" width="172" height="180">

Dreamweaver centralizes all its image functions in the Property inspector. The Image Property inspector, shown in Figure 9-12, displays a small thumbnail of the image as well as its file size. Dreamweaver automatically inserts the image filename in the Src text box (as the src attribute). To replace a currently selected image with another, click the folder icon next to the Src text box, or double-click the image itself. This sequence opens the Select Image Source dialog box. When you've selected the file, Dreamweaver automatically refreshes the page and corrects the code.

Figure 9-12. The Image Property inspector gives you total control over the HTML code for every image.

If the Image Property inspector is open when you insert your image, you can begin to modify the image attributes immediately.

When you first insert a graphic into the page, the Image Property inspector displays a blank text box next to the thumbnail and file size. Fill in this box with a unique name for the image, to be used in JavaScript and other applications.

The width and height attributes are important because browsers build Web pages faster when they know the size and shape of the included images. Dreamweaver reads these attributes when the image is first loaded. The width and height values are initially expressed in pixels and are automatically inserted as attributes in the HTML code.

Browsers can dynamically resize an image if its height and width on the page are different from the original image's dimensions. For example, you can load your primary logo on the home page and then use a smaller version of it on subsequent pages by inserting the same image with reduced height and width values. Because you're only loading the image once and the browser is resizing it, download time for your Web page can be significantly reduced.

Note

Resizing an image just means changing its appearance onscreen; the file size stays exactly the same. To reduce a file size for an image, you need to scale it down in a graphics program such as Fireworks or, once you've resized it in Dreamweaver, click Resample in the Property inspector.

To resize an image in Dreamweaver, select the image and type the desired number of pixels in the Property inspector's H (height) and W (width) fields. With Dreamweaver, you can also visually resize your graphics by using the click-and-drag method. A selected image has three sizing handles located on the right, bottom, and lower-right corners of its bounding box. Click any of these handles and drag it out to a new location—when you release the mouse, Dreamweaver resizes the image. To maintain the current height/width aspect ratio, hold down the Shift key after starting to drag the corner sizing handle.

If you alter either the height or the width of an image, Dreamweaver displays the Property inspector values in bold in their respective fields. You can restore an image's default measurements by clicking the H or the W independently—or you can click the Reset Size button to restore both values.

Warning

If you elect to enable your viewer's browser to resize your image on-the-fly using the height/width values you specify, keep in mind that the browser is not a graphics-editing program and that its resizing algorithms are not sophisticated. View your resized images through several browsers to ensure acceptable results.

You can offset images with surrounding whitespace by using the margin attributes. The amount of whitespace around your image can be designated both vertically and horizontally through the vspace and hspace attributes, respectively. These margin values are entered, in pixels, into the V Space and H Space text boxes in the Image Property inspector.

The V Space value adds the same amount of whitespace along the top and bottom of your image; the H Space value increases the whitespace on the left and right sides of the image. These values must be positive; HTML doesn't allow images to overlap text or other images (outside of AP elements). Unlike in page layout, negative whitespace does not exist.

Note

The hspace and vspace attributes are deprecated in HTML 4.0. This means that, although the attributes are currently still supported, another preferred method achieves the same effect in newer browsers. In most cases, the margins should be implemented using Cascading Style Sheets, described in Chapter 7.

It's easy for Web designers to get caught up in the visual design of their Web pages; after all, designers can devote hours to creating a single graphic or to perfectly positioning a graphic on the page relative to other information. Remember, however, that graphics aren't the most effective communication method in every circumstance. Luckily, the <img> tag includes two attributes that enable you to describe your image using plain text: alt and longdesc.

The alt attribute gives you a means to include a short description of a graphic. It is used in many ways:

As a page is loading over the Web, the image is first displayed as an empty rectangle if the

<img>tag contains width and height information. Some browsers display thealtdescription in this rectangle while the image is loading, offering the waiting user a written preview of the forthcoming image.In many browsers, the

alttext displays as a tooltip when the user's pointer passes over the graphic.A real benefit of

alttext is providing input for browsers that don't show graphics. Remember that text-only browsers are still in use, and some users, interested only in content, turn off the graphics to speed up the text display.The W3C is working toward standards for browsers for the visually impaired, and the

alttext can be used to describe the image.

For all these reasons, it's good coding practice to associate an alt description with all your graphics. In Dreamweaver, you can enter this alternative text in the Alt text box of the Image Property inspector.

Tip

If the <img> tag does not contain an alt attribute, some screen readers read the filename when they encounter the image, which slows down how quickly visually impaired users can get to the real information on your page. For images that are purely visual and don't contribute to the meaning of your content, such as bullets or spacer images, include a blank alt attribute. To do this, open the Image Property inspector and select <empty> from the Alt drop-down list.

Currently, the alt attribute is the most valuable tool you have for providing a textual description of your images. However, some images are just too complicated to describe in a few words and are too important to gloss over. For these situations, the latest HTML specification includes the longdesc attribute. Although none of the major browsers currently support this attribute, Dreamweaver is anticipating the future by enabling you to specify a longdesc for your images.

In Dreamweaver, choose Edit

Figure 9-13. The Image Tag Accessibility Attributes dialog box appears when you select the Images option in the Accessibility Preferences.

Warning

The Image Tag Accessibility Attributes dialog box is not displayed if you add a new image by dragging it from the Files panel. It does appear, however, if you drag the image from the Assets panel, or use the Insert bar or Insert menu to add the image.

When you're working with thumbnails (small versions of images) on your Web page, you may need a quick way to distinguish one from another. The border attribute enables you to place a one-color rectangular border around any graphic. To turn on the border, enter the desired width of the border, measured in pixels, in the Border text box located on the lower half of the Image Property inspector. Entering a value of 0 explicitly turns off the border.

Note

A preferred method for adding a border to an image is to use Cascading Style Sheets, described in Chapter 7. Note that Cascading Style Sheets are not supported in older browsers.

One of the most frequent cries for help among beginning Web designers results from the sudden appearance of a bright blue border around an image. Whenever you assign a link to an image, HTML automatically places a border around that image; the color is determined by the Page Properties Link color, where the default is bright blue. Dreamweaver intelligently assigns a 0 to the border attribute whenever you enter a URL in the Link text box. If you've already declared a border value and enter a link, Dreamweaver won't zero-out the border. You can, of course, override the no-border option by entering a value in the Border text box.

Another option for loading Web page images, the lowsrc attribute, displays a smaller version of a large graphics file while the larger file is loading. The lowsrc file can be a grayscale version of the original, or a version that is physically smaller or reduced in color or resolution. This option is designed to significantly reduce the file size for quick loading.

Select your lowsrc file by clicking the file icon next to the Low Src text box in the Image Property inspector. The same criteria that apply to inserting your original image also apply to the lowsrc picture.

Tip

One handy lowsrc technique first proportionately scales down a large file in a graphics-processing program. This file becomes your lowsrc file. Because browsers use the final image's height and width information for both the lowsrc and the final image, your visitors immediately see a blocky version of your graphic, which is replaced by the final version when the picture is fully loaded.

Just like text, images can be aligned to the left, right, or center. In fact, images have much more flexibility than text in terms of alignment. In addition to the same horizontal alignment options, you can align your images vertically in nine different ways. You can even turn a picture into a floating image type, enabling text to wrap around it.

When you change the horizontal alignment of a line—from left to center or from center to right—the entire paragraph moves. Any inline images that are part of that paragraph also move. Likewise, selecting one of a series of inline images in a row and realigning it horizontally causes all the images in the row to shift.

In Dreamweaver, the horizontal alignment of an inline image is changed in exactly the same way that you realign text—with the alignment buttons found on the Image Property inspector. As with text, buttons exist for left, center, and right. Although these are very conveniently placed on the Image Property inspector, the alignment attribute is actually written to the <p> or other block element enclosing the image.

Tip

The align attribute, whether attached to a <p> tag for horizontal alignment, or to an <img> tag for vertical alignment (as described in the following section), is deprecated in HTML 4.0. Instead of using the align attribute, you can use Cascading Style Sheets, described in Chapter 7.

Because you can place text next to an image—and images vary so greatly in size—HTML includes a variety of options for specifying just how image and text line up. As you can see from the chart shown in Figure 9-14, a wide range of possibilities is available.

To change the vertical alignment of any graphic in Dreamweaver, open the Align drop-down list in the Image Property inspector and choose one of the options. Dreamweaver writes your choice into the align attribute of the <img> tag. The various vertical alignment options are listed in Table 9-1, and you can refer to Figure 9-14 for examples of each type of alignment.

Table 9-1. Vertical Alignment Options

Option | Result |

|---|---|

Browser Default | No alignment attribute is included in the |

Baseline | The bottom of the image is aligned with the baseline of the surrounding text. |

Top | The top of the image is aligned with the top of the tallest object in the current line. |

Middle | The middle of the image is aligned with the baseline of the current line. |

Bottom | The bottom of the image is aligned with the baseline of the surrounding text. |

Text Top | The top of the image is aligned with the tallest letter or object in the current line. |

Absolute Middle | The middle of the image is aligned with the middle of the tallest text or object in the current line. |

The bottom of the image is aligned with the descenders (as in y, g, p, and so forth) that fall below the current baseline. | |

Left | The image is aligned to the left edge of the browser or table cell, and all text in the current line flows around the right side of the image. |

Right | The image is aligned to the right edge of the browser or table cell, and all text in the current line flows around the left side of the image. |

The last two alignment options, Left and Right, are special cases; details about how to use their features are covered in the following section.

Most browsers support wrapping text around an image on a Web page—long a popular design option in conventional publishing. As noted in the preceding section, the Left and Right alignment options turn a picture into a floating image type. This type is so called because the image can move depending on the amount of text and the size of the browser window.

Tip

Using both floating image types (Left and Right) in combination, you can actually position images flush-left and flush-right, with text in the middle. Insert both images side by side and then set the leftmost image to align left and the rightmost one to align right. Insert your text immediately following the second image.

Your text wraps around the image depending on where the floating image is placed (or anchored). If you enable the Anchor Points for Aligned Elements option in the Invisible Elements category of Preferences, Dreamweaver inserts a Floating Image Anchor symbol to mark the floating image's place. Note that the image itself may overlap the anchor, hiding the anchor from view. Figure 9-15 shows two examples of text wrapping: a left-aligned image with text flowing to the right, and a right-aligned image with text flowing to the left.

The Floating Image Anchor is not just a static symbol. You can click and drag the anchor to a new location and cause the paragraph to wrap in a different fashion. Be careful, however. If you delete the anchor, you also delete the image it represents.

You can also wrap a portion of the text around your left- or right-aligned picture and then force the remaining text to appear below the floating image. However, Dreamweaver cannot currently insert the HTML code necessary to do this task through the Image Property inspector. You have to force an opening to appear by inserting a break tag, with a special clear attribute, where you want the text to break. This special <br> tag has three forms:

<br clear=left>—Causes the line to break and the following text to move down vertically until no floating images are on the left<br clear=right>—Causes the line to break and the following text to move down vertically until no floating images are on the right<br clear=all>—Moves the text following the image down until no floating images are on either the left or the right

A quick way to add the clear attribute is to position your cursor where you want the text to break, and press Shift+Enter. Next, in Code view, right-click the <br> tag and select Edit Tag <br> from the context menu. The Tag Editor dialog box displays; select the appropriate Clear option and click OK.

In this chapter, you've learned about working with the surface graphics on a Web page. You can also place an image in the background of an HTML page. This section covers some of the basic techniques for incorporating a background image in your Dreamweaver page.

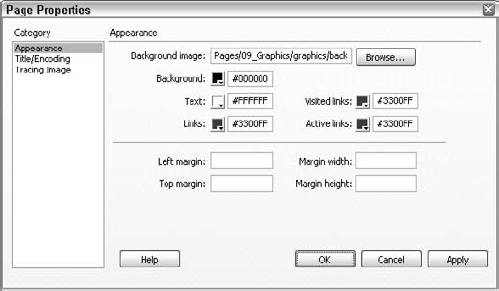

Add an image to your background either by using Cascading Style Sheets (CSS) or by modifying the Page Properties. The Cascading Style Sheet method is preferred because it gives you additional control over your background image. However, older browser versions do not support Cascading Style Sheets; if you must support browser versions earlier than Internet Explorer 4.0 and Netscape Navigator 4.0, you are limited to changing the Page Properties.

Note

If you aren't familiar with Cascading Style Sheets, you may want to read Chapter 7 before trying the following procedure. That chapter gets you started with general CSS concepts and outlines specific options for implementing background images.

To implement a background image using Cascading Style Sheets, follow these steps:

Choose Window

On the CSS Styles panel, click Edit Styles and then click the New CSS Style button.

In the New Style dialog box, choose Redefine HTML Tag, and in the Tag drop-down list, select Body. These selections create a background image for the entire document. You can also select a different tag or choose the Make a Custom Style option to assign a background image to a single element on the page, such as a table cell or paragraph.

Specify whether you want to save the style definition in an external style sheet or in the current document, and then click OK.

In the CSS Style Definition dialog box, select the Background category.

In the Background Image field, type the path and filename for the image file, or click Browse to navigate to the file.

Designate any other background options, and then click OK.

To specify a background image using the Page Properties, choose Modify

There are two key differences between background images and the foreground inline images discussed in the preceding sections of this chapter. First and most obvious, all other text and graphics on the Web page are superimposed over your chosen background image. This capability can bring extra depth and texture to your work; unfortunately, you have to make sure the foreground text and images work well with the background.

Basically, you want to ascertain that enough contrast exists between foreground and background. You can set the default text and the various link colors using Cascading Style Sheets or through the Page Properties dialog box, shown in Figure 9-16. When trying out a new background pattern, you should set up some dummy text and links. Then click the Apply button on the Page Properties dialog box to test different color combinations.

Figure 9-16. If you're using a background image, be sure to check the default colors for text and links to make sure enough contrast exists between background and foreground.

The second distinguishing feature of background images is that the viewing browser completely fills either the browser window or the area behind the content of your Web page; whichever is larger. Suppose you have created a splash page with only a 200 × 200 foreground logo, and you've incorporated an amazing 1,024 × 768 background that took you weeks to compose. No one can see the fruits of your labor in the background—unless he resizes his browser window to 1,024 × 768. On the other hand, if your background image is smaller than either the browser window or what the Web page content needs to display, the browser and Dreamweaver repeat (tile) your image to make up the difference.

If you implement the background image using Page Properties, the image always tiles both horizontally and vertically, filling the page as just described. But if you implement your background image using Cascading Style Sheets, you can control whether the image tiles horizontally, vertically, in both directions, or not at all.

Tip

With Cascading Style Sheets, you not only can attach a background image to a page, but you can also attach a background image to an individual element on a page, such as a single paragraph. Cascading Style Sheets also enable you to designate whether the background image should scroll with the foreground text, or if it should remain stationary while the foreground text scrolls over the background. These options are not available with the Page Properties method.

HTML includes a standard horizontal cline that can divide your Web page into specific sections. The horizontal rule tag, <hr>, is a good tool for adding a little diversion to your page without adding download time. You can control the width (either absolutely or relative to the browser window), the height, the alignment, and the shading property of the rule. These horizontal rules appear on a line by themselves; you cannot place text or images on the same line as a horizontal rule.

To insert a horizontal rule in your Web page in Dreamweaver, follow these steps:

Place your cursor where you want the horizontal rule to appear.

From the Common category of the Insert bar, click the Horizontal Rule button or choose Insert

To change the width of the line, enter a value in the Property inspector width (W) text box. You can insert either an absolute width in pixels or a relative value as a percentage of the screen:

To set a horizontal rule to an exact width, enter the measurement in pixels in the width (W) text box and press the Tab key. If it is not already showing, select Pixels in the drop-down list.

To set a horizontal rule to a width relative to the browser window, enter the percentage amount in the width (W) text box, press the Tab key, and select the percent sign (%) in the drop-down list.

To change the height of the horizontal rule, type a pixel measurement in the height (H) text box.

To change the alignment from the default (centered), open the Align drop-down list and choose another alignment.

To disable the default embossed look for the rule, clear the Shading checkbox.

If you intend to reference your horizontal rule in JavaScript or in another application, you can give it a unique name. Type the name in the unlabeled text box located directly to the left of the H text box.

Note

The HTML 4.0 standard lists the align, noshade, width, and size attributes of the <hr> tag as deprecated. However, current browsers still support these attributes.

To modify any inserted horizontal rule, simply click it. (If the Property inspector is not already open, you have to double-click the rule.) As a general practice, size your horizontal rules using the percentage option if you are using them to separate items on a full screen. If you are using the horizontal rules to divide items in a specifically sized table column or cell, use the pixel method.

Tip

The Shading property of the horizontal rule is most effective when your page background is a shade of gray. The default shading is black along the top and left, and white along the bottom and right. The center line is generally transparent (although Internet Explorer enables you to assign a color attribute). If you use a different background color or image, be sure to check the appearance of your horizontal rules in that context.

Many designers prefer to create elaborate horizontal rules; in fact, custom rules are an active area of clip art design. These types of horizontal rules are regular graphics and are inserted and modified as such.

Why include a section on animation in a chapter on inline images? On the Web, animations are, for the most part, inline images that move. Outside of the possibilities offered by Dynamic HTML (covered in Part IV), Web animations typically are either animated GIF files or are created with a program such as Flash that requires a plugin. This section takes a brief look at the capabilities and uses of GIF animations.

A GIF animation is a series of still GIF images flipped rapidly to create the illusion of motion. Because animation-creation programs compress all the frames of the animation into one file, a GIF animation is placed on a Web page in the same manner as a still graphic.

In Dreamweaver, click the Image button in the Insert bar or choose Insert

As you can imagine, GIF animations can quickly grow to be very large. The key to controlling file size is to think small: Keep your images as small as possible with a low bit-depth (number of colors) and use as few frames as possible.

To create your animation, use any graphics program to produce the separate frames. One excellent technique uses an image-processing program such as Adobe Photoshop and progressively applies a filter to the same image over a series of frames. Figure 9-18 shows the individual frames created with Photoshop's Lighting Effects filter. When animated, a spotlight appears to move across the word.

You need an animation program to compress the separate frames and build your animated GIF file. Many commercial programs, including Adobe's Fireworks, can handle GIF animation. QuickTime Pro can turn individual files or any other kind of movie into an animated GIF, too. Most animation programs enable you to control numerous aspects of the animation: the number of times an animation loops, the delay between frames, and how transparency is handled within each frame.

Figure 9-18. The five images shown are frames of an animated GIF image that are compressed into one file using an image-editing program.

Tip

If you want to use an advanced animation tool but still have full backward compatibility, check out Flash, from Adobe. Flash is best known for outputting small vector-based animations that require a plugin to view, but it can also save animations as GIFs or AVIs. See Chapter 25 for more information.

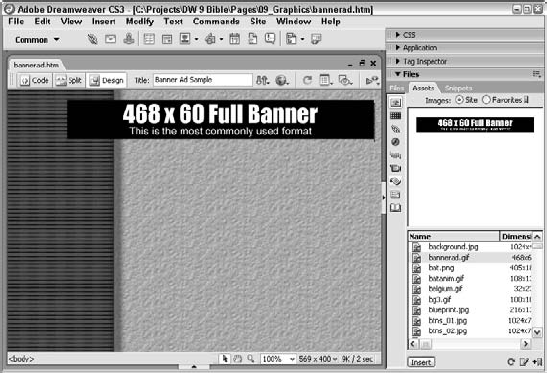

Banner ads have become an essential aspect of the World Wide Web; for the Web to remain, for the most part, freely accessible, advertising is needed to support the costs. Banner ads have evolved into the de facto standard. Although numerous variations exist, a banner ad is typically an animated GIF of a particular width and height, within a specified file size.

The Standards and Practices Committee of the Interactive Advertising Bureau (IAB) established a series of standard sizes for banner ads. Although no law dictates that these guidelines have to be followed, the vast majority of commercial sites adhere to the suggested dimensions. The most common banner sizes (in pixels) and their official names are listed in Table 9-2; additional banner guidelines are available at the IAB Web site (www.iab.net).

Table 9-2. IAB Advertising Banner Sizes

Dimensions | Name |

|---|---|

468 × 60 | Full Banner |

234 × 60 | Half Banner |

88 × 31 | Micro Bar |

120 × 90 | Button 1 |

120 × 60 | Button 2 |

120 × 240 | Vertical Banner |

125 × 125 | Square Button |

728 × 90 | Leaderboard |

160 × 600 | Wide Skyscraper |

120 × 600 | Skyscraper |

Acceptable file size for a banner ad is not as clearly specified, but it's just as important. The last thing a hosting site wants is for a large, too-heavy banner to slow down the loading of its page. Most commercial sites have an established maximum file size for any given banner ad size. Generally, banner ads are around 10KB, and no more than 12KB. The lighter your banner ad, the faster it loads and—as a direct result—the more likely Web page visitors stick around to see it.

Note

Major sites often have additional criteria for using rich media in banner ads, such as Flash animations or JavaScript. These may include file size, length of animation, behavior when the ad is clicked, and so on.

Inserting a banner ad on a Web page is very straightforward. As with any other GIF file, animated or not, all you have to do is insert the image and assign the link. As any advertiser can tell you, the link is as important as the image itself, and you should take special care to ensure that it is correct when inserted. Advertising links are often quite complex because they not only link to a specific page, but may also carry information about the referring site. Several companies monitor how many times an ad is selected—the clickthru rate—and often a CGI program is used to communicate with these companies and handle the link. Here's a sample URL from CNet's News.com site:

xxxhttp://home.cnet.com/cgi-acc/clickthru.acc?clickid=00001e145ea7d80f00000000&adt=003:10:100&edt=cnet&cat=1:1002:&site=CN

Obviously, copying and pasting such URLs is highly preferable to entering them by hand.

Advertisements often come from an outside source, so a Web page designer may have to allow space for the ad without incorporating the actual ad. Some Web designers create a plain rectangular image of the appropriate size to serve as a placeholder, until the actual image is ready. In Dreamweaver, placeholder ads can easily be maintained as Library items and placed as needed from the Assets panel, as shown in Figure 9-19.

Note

See Chapter 29 for information on creating and using Dreamweaver Library items.

If you'd prefer not to use placeholder graphics as just described, you can instead insert a plain <img> tag—with no src parameter. When an <img> tag without a src attribute is in the code, Dreamweaver displays a plain rectangle that can be resized to the proper banner ad dimensions in the Property inspector.

You can insert a placeholder image by clicking the Image Placeholder button on the Insert bar, or by choosing Insert

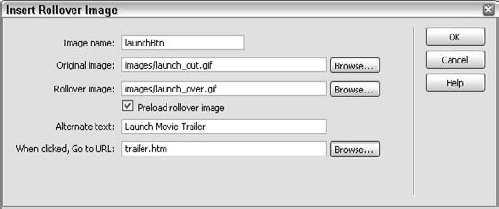

Rollovers are among the most popular of all Web page effects. A rollover (also known as a mouseover) occurs when the user's pointer passes over an image and the image changes in some way. It may appear to glow or change color and/or shape. When the pointer moves away from the graphic, the image returns to its original form. The rollover indicates interactivity, and attempts to engage the user with a little bit of flair.

Rollovers are usually accomplished with a combination of HTML and JavaScript. Dreamweaver was among the first Web-authoring tools to automate the production of rollovers through its Swap Image and Swap Image Restore behaviors. Later versions of Dreamweaver make rollovers even easier with the Rollover Image object. With the Rollover Image object, you just pick two images to make a rollover.

Note

If you use Fireworks as your image-editing tool, refer to Chapter 24 to learn another method for creating rollover images.

Technically speaking, a rollover is accomplished by manipulating an <img> tag's src attribute. Recall that the src attribute is responsible for providing the actual filename of the graphic to be displayed; it is, quite literally, the source of the image. A rollover changes the value of src from one image file to another. Swapping the src value is analogous to having a picture within a frame and changing the picture while keeping the frame.

Warning

The picture frame analogy is appropriate on one other level: It serves as a reminder of the size barrier inherent in rollovers. A rollover changes only one property of an <img> tag, the source—it cannot change any other property, such as height or width. For this reason, both your original image and the image displayed during the rollover should be the same size. If they are not, the alternate image is resized to match the dimensions of the original image.

Dreamweaver's Rollover Image object automatically changes the image back to its original source when the user moves the pointer off the image. Optionally, you can elect to preload the images with the selection of a checkbox. Preloading is a Web page technique that reads the intended file or files into the browser's memory before they are displayed. With preloading, the images appear on demand, without any download delay.

Rollovers are typically used for buttons that, when clicked, open another Web page. In fact, JavaScript requires that an image include a link before it can detect when a user's pointer moves over it. Dreamweaver automatically includes the minimum link necessary: the # link. Although JavaScript recognizes this symbol as indicating a link, no action is taken if the image is clicked by the user; the #, by itself, is an empty link. You can supply whatever link you want in the Rollover Image object.

Tip

Some browsers link to the top of the page when they encounter a # link. If you want to create a rollover image that doesn't link anywhere, change the # to the following:

javascript:;

You can change this directly in Code view, or in the Link field of the Property inspector for the button.

To include a Rollover Image object in your Web page, follow these steps:

Place your cursor where you want the rollover image to appear and choose Insert

You can enter a unique name for the image in the Image Name text box, or you can use the name automatically generated by Dreamweaver.

In the Original Image text box, enter the path and name of the graphic you want displayed when the user's mouse is not over the graphic. You can also click the Browse button to select the file. Press Tab when you're done.

In the Rollover Image text box, enter the path and name of the graphic file you want displayed when the user's pointer is over the image. You can also click the Browse button to select the file.

In the Alternate Text field, type a brief description of the graphic button.

If desired, specify a link for the image by entering it in the When Clicked, Go To URL text box or by clicking the Browse button to select the file.

To enable images to load only when they are required, deselect the Preload Images option. Generally, it is best to leave this option selected (the default) so that the appearance of the rollover is not delayed.

Click OK when you're finished.

Tip

Keep in mind that the Rollover Image object inserts both the original image and its alternate, whereas the Swap Image technique is applied to an existing image in the Web page. If you prefer to use the Rollover Image object rather than the Swap Image behavior, nothing prevents you from deleting an existing image from the Web page and inserting it again through the Rollover Image object. Just make sure that you note the path and name of the image before you delete it, so you can find it again.

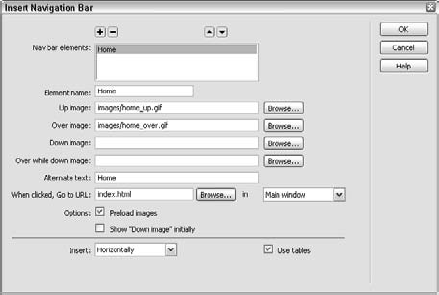

Rollovers are nice effects, but a single button does not constitute a navigation system for a Web site. Typically, several buttons with a similar look and feel are placed next to one another to form a navigation bar. To make touring a site as intuitive as possible, the same navigation bar should appear on each page. You can achieve this effect by placing a copy of the navigation bar on each page, or by creating a frameset with one frame containing the navigation bar. Consistency of design and repetitive use of the navigation bar simplifies getting around a site—even for a first-time user.

Some designers build their navigation bars in a separate graphics program and then import them into Dreamweaver. Adobe Fireworks, with its capability to export both images and code, makes this a strong option. Other Web designers, however, prefer to build separate rollover images in a graphics program and then assemble all the pieces at the HTML layout stage. Dreamweaver automates such a process with its Navigation Bar object.

The Navigation Bar object incorporates rollovers—and more. A Navigation Bar element can use up to four different images, each reflecting a different user action:

Up: The user's pointer is away from the image.

Over: The pointer is over the image.

Down: The user has clicked the image.

Over While Down: The user's pointer is over the image after it has been clicked.

One key difference separates a fully functioning navigation bar from a group of unrelated rollovers. When the Down state is available, if the user clicks one of the buttons, any other Down button is changed to the Up state. The effect is like a series of mutually exclusive radio buttons: You can show only one selected in a group. The Down state is often used to indicate the current selection.

Tip

Although you can use the Navigation Bar object on any type of Web design, it works best in a frameset context, with one frame for navigation and one for content. If you insert a navigation bar with Up, Over, Down, and Over While Down states for each button in the navigation frame, you can target the content frame and gain the full effect of the mutually exclusive Down states.

Before you can use Dreamweaver's Navigation Bar object, you have to create a series of images for each button—one for each state you plan to use, as demonstrated in Figure 9-21. It's completely up to the designer how the buttons appear, but it's important that a consistent look and feel be applied to all the buttons in a navigation bar. For example, if the Over state for Button A reveals a green glow, rolling over Buttons B, C, and D should cause the same glow.

Figure 9-21. Before you invoke the Navigation Bar object, create a series of buttons, using a separate image for each state to be used.

To insert a navigation bar, follow these steps:

From the Insert bar, click the Images: Navigation Bar button. The Insert Navigation Bar dialog box appears, as shown in Figure 9-22.

Enter a unique name for the first button in the Element Name field and press Tab.

Warning

Be sure to use Tab rather than Enter (Return) when moving from field to field. When Enter (Return) is pressed, Dreamweaver attempts to build the navigation bar. If you have not completed the initial two steps (providing an Element Name and a source for the Up Image), an alert is displayed; otherwise, the navigation bar is built.

In the Up Image field, enter a path and filename or browse to a graphic file to use.

Select files for each of the remaining states: Over, Down, and Over While Down. If you don't want to use all four states, just specify the same image more than once. For example, if you don't want a separate Over While Down state, use the same image for Down and Over While Down.

If you want, enter a brief description of the button in the Alternate Text field.

Enter a URL or browse to a file in the When Clicked, Go To URL field.

Tip

If you do not enter a URL, Dreamweaver inserts a hash mark (#) in the generated code to create a null link for the button. Although the hash mark is supposed to cause a jump to nowhere when the button is clicked, the hash mark actually causes some browsers to jump to the top of the page. Although this is unusual in a navigation bar, if you want to create a button that doesn't link anywhere, consider entering

javascript:;in the Go To URL field to create a null link that won't cause browsers to jump to the top of the page.If you're using a frameset, select a target for the URL from the drop-down list adjacent to the Browse button.

Enable or disable the Preload Images option as desired. For a multistate button to be effective, the reaction has to be immediate, and the images must be preloaded. It is highly recommended that you enable the Preload Images option.

If you want the current button to display the Down state first, select the Show "Down Image" Initially option. When this option is chosen, an asterisk appears next to the current button in the Nav Bar Elements list. Generally, you don't want more than one Down state showing at a time.

To set the orientation of the navigation bar, select either Horizontally or Vertically from the Insert drop-down list.

If you want to contain your images in a table, keep the Use Tables option selected. If you decide not to use tables in a horizontal configuration, images are presented side by side; when you don't use tables in a vertical configuration, Dreamweaver separates every element with line breaks (

<br>tag).Click the Add (+) button and repeat steps 2 through 9 to add the next element.

To reorder the elements in the navigation bar, select an element in the Nav Bar Elements list and use the Up and Down buttons to reposition it in the Elements list.

To remove an element, select it and click the Delete (–) button.

Each page can have only one Dreamweaver-built navigation bar. If you try to insert a second, Dreamweaver asks if you'd like to modify the existing series. Clicking OK opens the Modify Navigation Bar dialog box, which is identical to the Insert Navigation Bar dialog box, except you can no longer change the orientation or table settings. You can also alter the inserted navigation bar by choosing Modify

Note

If you're looking for even more control over your navigation bar, Dreamweaver also includes the Set Nav Bar Image behavior, which is fully covered in Chapter 12.

In this chapter, you learned how to include both foreground and background images in Dreamweaver. Understanding how images are handled in HTML is an absolute necessity for the Web designer. As you're inserting images into your Web pages, keep these key points in mind:

Web pages are restricted to using specific graphic formats. Virtually all browsers support GIF and JPEG files. PNG finally seems to be gaining acceptance, but it is not universally viewable without additional plugins. Dreamweaver can preview all three image types.

Images are inserted in the foreground in Dreamweaver through the Image button on the Insert bar or from the Assets panel. After the graphic is inserted, almost all modifications can be handled through the Property inspector.

You can use HTML's background image function to lay a full-frame image or a tiled series of the same image underneath your text and graphics. Tiled images can be employed to create columns and other designs with small files.

Simple graphic editing chores—including cropping and resampling—are available right from Dreamweaver's Property inspector; for finer control, you'll need a graphics editor installed and then you can use either the Optimize Image or Edit options.

The simplest HTML graphic is the built-in horizontal rule. It is useful for dividing your Web page into separate sections. You can size the horizontal rule either absolutely or relatively.

Animated images can be inserted alongside and in the same manner as still graphics. The individual frames of a GIF animation must be created in a graphics program and then combined in an animation program.

With the Rollover Image object, you can easily insert simple rollovers that use two different images. To build a rollover that uses more than two images, you have to use the Swap Image behavior.

You can add a series of interrelated buttons—complete with four-state rollovers—by using the Navigation Bar object.

In the next chapter, you learn how to use hyperlinks in Dreamweaver.