Chapter Six. Retrospective Exercises

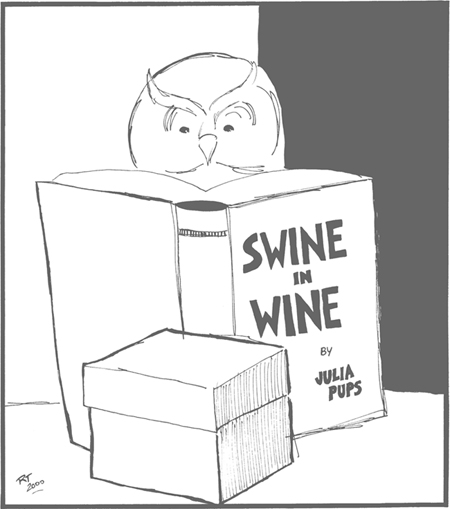

Owl picked up Singed-Tail’s copy of Swine in Wine and quickly became intrigued. It wasn’t the recipes themselves but the overall structure of the cookbook that caught his immediate interest. Leafing through it, he realized that the cookbooks he’d used had had the same structure as this book, with the first part including general information, the second part containing recipes, and the final section presenting special topics and suggestions on what the reader might explore next.

It struck Owl that this three-part format let a reader browse while planning a menu. Although he knew that cookbook authors do not expect each and every recipe to be read or every dish to be prepared, he realized the value in a reader being able to look through all the recipes. Each cook is expected to use his or her own imagination, and to consider the guests’ preferences, the available ingredients, the desired mood of the meal, and so forth, when choosing a menu. By using the cookbook author’s ideas as well as his or her own preferences, the cook can design a perfect, unique meal for any situation.

This concept excited Owl. He thought back to the times that Bee or Ant or Singed-Tail had come to him for advice and had then commented on how much easier life would be if it came with instructions, just like a cookbook. At the time, he had wondered whether his friends were asking for a cookbook on how to live life, or for one simple recipe. He concluded that his friends were hoping for one single piece of advice that would guide them. But, as he had already explained to Bee after Bee’s disastrous real-estate experience with Ant, “One size does not fit all.”

Owl decided he would write a cookbook—one in which each “dish” would consist of a piece of sage wisdom. He would leave it up to the reader, however, to select the combination of dishes that fit the occasion.

Using Owl’s insight and a modified cookbook approach, we can design retrospectives in which individual exercises are like dishes that make up a meal. In this chapter, I provide a variety of exercises. You can browse through these exercises while you think about how well one or another or a combination of several might fit your particular retrospective. In all likelihood, you will pick a few exercises and leave the remainder for other times. Or, you may wish to use an exercise of your own design or one which you discovered someplace else. Select each component to complement and support the other selections, not to duplicate or compete with them. Each exercise must add something unique to the retrospective and contribute to the whole so that the complete retrospective experience (rather than a single exercise) is remembered as a positive professional experience.

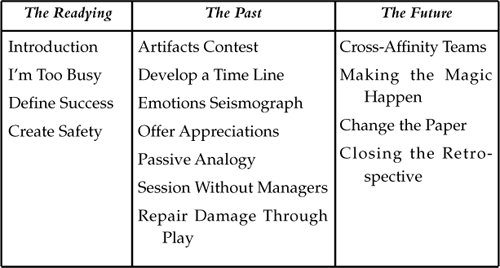

Like a meal, your retrospective can have a number of courses, with each one designed to accomplish certain goals and to prepare the participants for the next course. I typically divide retrospectives into three courses, which I call the Readying, the Past, and the Future. These courses are described in the paragraphs below.

The Readying: The Readying course prepares community members for exploration of what went on in their project. It provides an initial period during which I can convey my strengths as facilitator to members of the community: I demonstrate my confidence in them, my competence, my attentiveness, my willingness to understand their problems, my flexibility, and my ability to maintain any needed control. In this Readying phase, I want members of the group to

• build a trust-based relationship with me

• become convinced that the process is likely to have a positive outcome

• adopt an attitude that allows discovery, openness, curiosity, enthusiasm, and risk-taking

• participate in the design of some activities in order to build ownership

• establish safety measures to ensure that the truth and people’s interpretations of events can be told without fear of retaliation

• design ground rules for behavior to be upheld throughout this retrospective

The Past: The purpose of this course is, literally, to dwell in the past, allowing individual team members to share their stories of the project and to help the group as a whole understand what really happened. Often, so much activity occurs during a project that no one person knows all that went on. During this part of the retrospective, members of the community can discover connections that they never before understood. They will have the opportunity to learn what the project really cost and how large it really was. They will be able to study the actual process, compare it with the intended process, and identify all problems. It is important to have everyone look at the damage that may have occurred to relationships and work to repair it. It is also important for members of the community to appreciate what was accomplished and to learn from each other through examination of their combined experiences. It’s a chance to marvel at how much was learned during the past project.

The Future: The purpose of the Future course is to focus on the next project. In this activity, the team explores ways to use what individuals have learned during the retrospective in order to improve the next effort. The whole community participates in the planning discussion, not just the managers. Planning at this point is not project planning, nor product planning, but process planning. For many of the team members, this will be the first time they will have consciously thought about the processes they use.

Wait, read that last sentence again. “Consciously thought about the processes” is important because it is at this point that the magic of a retrospective occurs. After carefully considering all details of the previous project, everyone on the team will be ready to try new methods. This is a teachable moment, when people are ready to make serious commitments to change their work practices. The buy-in is there—that is, the collective understanding of what might happen if they don’t change and the group’s understanding of why change is necessary. This is the perfect time for a team to identify its own process and to work toward improving it.

The real power of a retrospective is in your hands during this Future course. Select exercises that empower the community to grow, dream, and act in ways that improve its work practice. As facilitator, you’ll need to use subtlety at this point. Since the goal is to empower the community to do its own work better, then only gentle leadership is called for—you are giving the power back to the community. At the same time, you are still responsible for guiding the retrospective process. I find that my responsibility during this course involves listening first and then offering ideas to help people sell their vision.

The Exercises

Now let’s look at the exercises that make up the possible offerings for each course. In the remainder of this chapter are exercises for a retrospective. Chapter 8 contains additional exercises but ones which are to be used with groups that participated in a failed or canceled project. As you may have guessed, the exercises are depicted in terms of courses in a meal and are modeled on the cookbook format. Pick and choose for best results.

Purpose: This exercise is designed to welcome the group, set the tone for the retrospective, and briefly cover procedural items such as agenda, break times, use of facilities, and so on.

When to use: Once—at the start of the retrospective.

Typical duration: 30 minutes. This activity needs to be short! Get through your introduction to the events scheduled for the retrospective quickly but without seeming to hurry.

Step 1: Get off to a quick start. First impressions are important, so try to make the activities interesting from the start. Here’s one idea: Begin the retrospective by asking people what the word “wisdom” means to them. Lead the discussion toward the understanding that wisdom is more than just being smart or being educated. Point out that elderly people are often believed to be wise. Why? What makes a 70-year-old person wise in comparison to a 19-year-old?

After the discussion has run its course, you may want to add your own observations. My view is that wisdom is the learning that comes from experience. I believe that each one of us can become wiser over time, but we do so only by learning from our successes and our failures. I see a retrospective as a chance to look back at what has occurred and to see what there is to be learned. I stress to team members that the goal is to capture the wisdom and lessons that are fresh in their minds from this last project.

If you think it will be helpful, give participants a copy of the “What Is a Retrospective?” handout presented in Chapter 5 of this book; stress again that this is not a hunt for the guilty. Introduce Kerth’s Prime Directive:

Regardless of what we discover, we must understand and truly believe that everyone did the best job he or she could, given what was known at the time, his or her skills and abilities, the resources available, and the situation at hand.

Step 2: Be sure people have been introduced. If you haven’t met everyone, or if you suspect all people in the room don’t know each other already, this is the time to make brief introductions.

Step 3: Discuss the schedule and agenda. A well-run event requires a schedule and an agenda. This having been said, you need to have the flexibility to adapt the retrospective as it proceeds. Address the two topics separately, recording details of each on its own flip chart. The schedule will be precise on the start and stop times, meals, breaks, and so on, and the agenda will list a few items that give direction and order.

Step 4: Alert people to any idiosyncrasies about the facilities. If there is anything that needs to be communicated about the facilities, this is the time to mention it. For me, this has included warnings about rattlesnakes in the rocks out back or elk droppings on the front lawn. More typically, you’ll need to provide directions to telephone banks and message centers, dress code details, earthquake safety procedures, or rules about tipping the staff. I usually ask one person to volunteer to act as our interface with the facilities staff. All requests should be funneled through this person so as to eliminate duplicated requests, conflicting messages, and problems of miscommunication.

Step 5: Provide the group with instant cameras. Memorable events occur during retrospectives. When possible, capture them in a snapshot. Hang the photos near the refreshment table or somewhere that the community is likely to gather. However, before you use a camera, check to see whether anyone objects to being photographed. If someone does object, discuss how to honor the objection while still leaving the group free to use the camera. The camera should be a resource for the entire community. Establish guidelines about camera protocol, as follows:

• If you see an event that would make a good picture, then grab the camera and take the picture.

• If you are worried about taking too many pictures, don’t worry—there’s plenty of film.

• If you end up in a photograph and are embarrassed, then please make the picture disappear.

• If you see any pictures that are especially meaningful to you, then feel free to take them home at the end of the retrospective.

The “I’m Too Busy” Exercise

Course: The Readying

Purpose: Sometimes, people think they are too busy to participate in a retrospective, believing that the three days could be used for something more important than talking about the past. This exercise is designed to awaken the curiosity of reluctant participants and thereby to help them want to participate.

When to use: Use occasionally, but do use as needed. Determine the need during your site visit before the retrospective. Listen for comments that indicate that people are skeptical that this is a good use of their time.

Typical duration: 30 minutes.

Background and theory: There are four reasons most commonly cited by people resisting a retrospective:

1. They fear the retrospective process might become a witch hunt.

2. They had a bad experience with a poorly run retrospective in the past.

3. They experienced no positive changes in the workplace as the result of a previous retrospective.

4. They feel overworked and pressured, tending to measure results by how much activity they have engaged in, not by what they’ve accomplished.

The first three reasons are addressed in other exercises and are relatively easy to handle in a well-run retrospective. The fourth is more difficult to dissuade people of and is addressed here.

Procedure:

Step 1: Acknowledge that three days is quite a long time for people to be away from their responsibilities. State that you understand that each person could accomplish a great deal on the job in that period of time. Rather than inviting discussion, pass out index cards and ask people to list what they would be working on if they weren’t in the retrospective—in other words, ask them to make “to do” lists.

Step 2: Direct people to think back on the past project. Tell them to count the number of days they felt were wasted because they didn’t know something then that they now know. State, “I’m looking for rough numbers—just give me your best guess.” Remain silent while they think through the project.

Step 3: Ask for a show of hands about the wasted days. Pose the following questions, waiting to count hands raised after each question. “How many of you found no more than one day?” “How many found no more than three days?” and finally, “How many found at least six days?” Usually, no hands go up for the first two questions, but practically everyone shoots a hand up for the third. People almost always discover that there were more than six days wasted on the last project!

Step 4: Lead people through a simple financial projection. Tell them, “If we spend the next three days learning what we can about this last project and if, as a result of what we learn, we can save at least six days on the next project, that is a one hundred percent return on your company’s investment. That seems to me to be a great return!”

Step 5: Build interest in the three-day commitment. Say, “I can easily show that we can find at least six days’ savings on the next project. Actually, my experience tells me that we can find a great deal more than that.” Ask each person to trust that the community will be able to accomplish this, but also ask people to confirm whether they believe this is a reasonable expectation. Confirmation is usually quick in coming, but be sure.

Step 6: Collect the “to do” lists. Pass a large envelope around the room and ask people to put their index cards in it. Reassure them, saying, “Don’t worry, these lists aren’t going away. I’ll give them back at the end. By collecting the cards, I mean to show that for the moment we’re putting this stuff on hold to see what we can learn.” By the time you get to the end of the retrospective three days later, most people will have forgotten about their lists. During the closing, you can bring out the envelope and ask whether people want their cards. I find it interesting that few people care about their lists after the retrospective is over. In fact, it is common to hear people comment that the concerns expressed on the cards seem irrelevant given all that has transpired during the retrospective.

The “Define Success” Exercise

Course: The Readying

Purpose: At the end of a project, most team members remember their very recent struggle to get the job done. They are so focused on the problems they encountered that they are not likely to step back and appreciate what they have accomplished. Even with the most seriously failed project, there are things about which a team can be proud. With a successful project, there are also things that can be improved upon.

In this exercise, I attempt to establish the idea that the project’s degree of success is not a relevant measure to use while people are trying to learn from their experiences. While not its goal, a benefit of this exercise is that it helps group members become comfortable with speaking openly—sharing what they think and having their opinions both heard and documented. They also learn to listen to other people’s ideas, possibly discovering that they have allies in the group who share their views.

When to use: If the project was completed, always include the “Define Success” Exercise. If the project was canceled, turn to the exercises in Chapter 8 for help.

Typical duration: 30 to 60 minutes, depending on how long presentation of the effort data requires.

Procedure: Using a group-discussion format, start the dialogue by asking, “Was this project a success?” As group members talk, record the reasons people give for believing it was or was not successful.

Somewhere in the middle of the exercise, present the effort data collected before the retrospective. Reflecting on this type of data will help the group focus on the big picture.

Often, the project was more successful than anyone realized. In the software industry, we have so many failed projects that the act of completing a software system and delivering it to a customer is an accomplishment in and of itself. If the particular project my retrospective is reviewing did come to completion, I cite industry data (from Capers Jones or Barry Boehm, for example) to suggest that the project was more successful than 85 percent of similar efforts. I might say, “If I were grading on a curve, I would give any project that gets completed at least a B+ without knowing the details.”

On the other hand, if the team insists on viewing the project as a failure, I let their truth stand. I then direct people’s attention toward learning from this failure so that they never have to experience such a negative event again.

Regardless of how the group as a whole views the success of the project, I generally close this exercise by offering a final definition of a successful project:

A successful project is one on which everybody says, “I wish we could do that over again—the very same way.”

With this concept fresh in people’s minds, I ask whether anyone thought the particular project met this definition. Usually, retrospective participants answer no. If that is the case, ask group members to think about what would have had to be different for them to answer yes. Then, ask them to take a few minutes to write down their thoughts.

This exercise will have been a success if participants have begun to give serious thought to what needs to be different, while considering what kind of project they would like to be a part of next time.

Background and theory: Effort data do not lie. When presented with effort data, people often discover that their impressions of the project have been wrong. Usually, far more work was accomplished than anyone realizes. Discovering this makes people curious about what other unexpected information might be learned during the retrospective.

The discussion of success establishes a precedent for talking openly about the project. The question posed is high-level and nonpersonal. Everyone has an opinion and can feel safe sharing it without the need to justify it. It becomes obvious that different opinions exist and all are to be tolerated. Also, the final definition of success sets a high standard for judging a project. It suggests that settling for less should be unacceptable. This idea may be novel enough to create even more group curiosity and enthusiasm.

The “Create Safety” Exercise

Course: The Readying

Purpose: At the beginning of a retrospective, people may have many fears that will prevent them from talking openly and honestly about the project. This exercise is designed to create a retrospective atmosphere that is safe, one in which team members can feel comfortable talking about important issues.

When to use: Whenever the practice of holding a retrospective is new. For teams in which a retrospective is common practice, safety may not be an issue. Make no assumptions and do some investigation before holding this exercise, but it’s quite possible that safety was established in previous retrospectives, and that all the team members naturally expect this event will be safe. In these situations, the safety exercise can be skipped.

Typical duration: One to two hours.

Procedure:

Step 1: Make everything optional. Stress that this process is not one of finding fault, but one of learning how to improve performance the next time. Establish that everything in this retrospective is optional by telling participants, “‘Optional’ means you don’t have to participate, you don’t have to talk, you don’t have to do any of the exercises that I assign. Each of you is the best judge of how you individually might acquire the most wisdom for yourself. I know that there may be moments when the most useful thing you can do is stay by yourself to sort issues out. I urge you to do whatever you need to do. The one thing I ask is that if you are not going to be meeting with us, just let me know beforehand.” Ask everyone in the group to agree to this ground rule, including the managers.

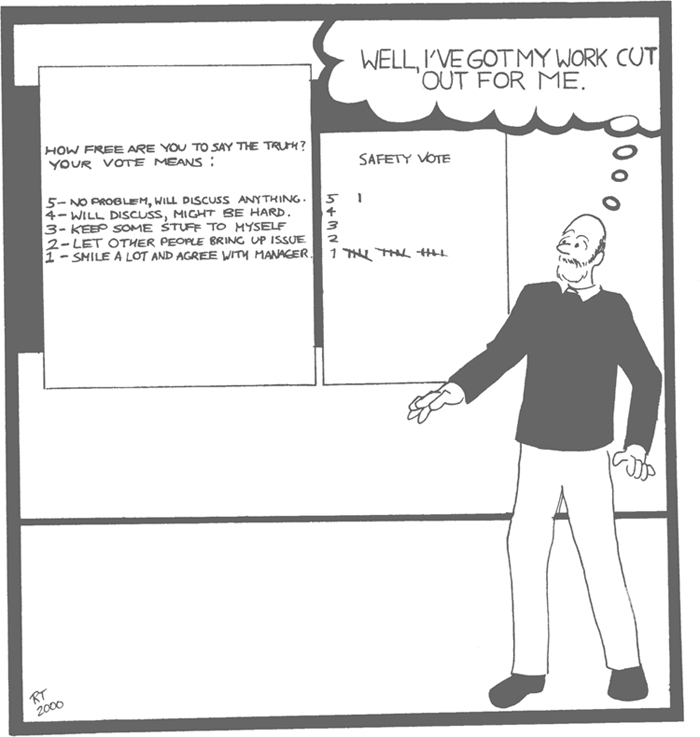

Step 2: Take a poll of how safe people feel. Remark to the group that there are managers in the room, and ask whether people feel safe enough to say what needs to be said. Tell the group that you need to measure the level of safety in the room. By means of secret ballots, take a vote on safety, using a rating scale of 1 to 5, in which “5” means “Hey, no problem, I’ll say anything.” A vote of “4” means “I’ll say most anything, but a few things might be hard to say.” A mid-scale “3” means “I’ll share some things, but keep a few things to myself.” Lower down, a “2” means “I’m not going to say much. Mostly, I’ll let other people bring up issues.” Lowest on the safety scale, a “1” means “I’ll smile, claim everything is great, and agree with whatever the managers say. No way will I let them know what I really think.”

Collect the votes, mark them on a flip chart, and make a dramatic show of placing the ballots into a briefcase and locking the case. Usually, there are some people who do not feel safe and give a rating of “1” or “2.” This is neither bad nor good. It’s simply information about the team’s interactions. I now try to change people’s feeling of “safety” by letting them work in groups composed of people with whom they are used to working.

Step 3: Create natural-affinity groups. Tell the community that this activity is a “no-talking” exercise, saying, “In a moment, I’m going to ask you to stand up and move about. I want you to move near people with whom you have worked closely on this project and away from people with whom you worked very little. Besides the no-talking rule, one other rule is that you can only move yourself. Out of this, we will form groups that have a natural affinity to be together. Any questions?”

Once people begin to move, urge them to keep looking around to see whether this grouping is accurate; if not, tell them to move themselves to better reflect affinity. Eventually, the group will come to a rest although you might notice a person who can’t stay put—he or she may have to shuttle between two or more groups. If this is the case, let it be, saying “Fine, it’s part of the way this group works.” Once people are settled, ask them to look around and comment on what they see. Ask the community to help you find the natural-affinity groups.

Next, send each group off to find a private space to discuss what can be done to make the retrospective safer. Ask people to take a flip chart and prepare a presentation to be made to the whole team. Tell them to “identify ground rules that would help, as well as other ideas that would increase safety.”

After about thirty minutes, reassemble everyone, giving individual groups time to report their ideas. Working with the community as a whole, figure out how to incorporate each idea into the retrospective.

As ground rules are suggested, present them to the entire team for approval. If discussion occurs, modify the ground rule as needed. Write the ground rules on a flip-chart page, to be hung in a prominent place in the room.

Some possible ground rules can be

• We will try not to interrupt.

• We will accept people’s opinions as neither right nor wrong, but just as opinions.

• We will speak from our own perspective.

• We will listen to everything someone has to say before we begin to develop a response.

• We will decide before we speak whether what we have to say is important enough to share at this time.

Every retrospective must include two additional important ground rules.

• All participation in the retrospective is optional.

• We will not make jokes about anyone in the room.

The final rule should be

• The ground rules can be amended after any break.

Besides establishing ground rules, the natural-affinity teams were asked to identify “other ideas that would increase safety.” Sometimes, a team will suggest an exercise, such as the “Session Without Managers” Exercise described later in this chapter.

Step 4: Revisit the measure of safety. After setting the ground rules, take a second ballot to measure how safe people now feel. Hopefully, you will see a positive change. While it’s nice if everyone in the room feels safe enough to vote “3” or above, that may not happen, as the situation described in the following True Story illustrates.

A True Story

I used to think I needed to get everyone up to a safety-level vote of at least a “3.” My reasoning was that the team needed to be able to hear the full, uncensored story to make sense of the experience.

My view on this changed when I facilitated a retrospective in which one vote remained a “1” no matter what we did to improve safety. We spent a great deal of time on several rounds of votes and safety-work sessions—to no avail. Everyone was pretty frustrated, so I called for a break and asked people to write confidential notes to me explaining their feelings. Here is the message I got from the holdout:

With that experience, I discovered that a lame-duck employee can cause a real problem in a retrospective if I expect everyone to feel safe. In this instance, I was fortunate because this individual was willing to share his secret.

Now if one or two people still feel unsafe after the second ballot, then I acknowledge that their worry is a reality for this group, and tell people that I hope that individual feelings of safety will change as the retrospective progresses. I point to the one or two low marks on the flip chart and say, “That’s a piece of information and we will see what comes up as we proceed. Just let it be for now.” Then I move on.

On the other hand, if most members of the community do not feel safe, then the whole retrospective needs to be redesigned to deal with that issue. There is no reason to go on. No other valid data will come from the retrospective.

Another True Story

One retrospective community I worked with spent a great deal of time wording the ground rules just right. Fear was high, and trust among members of the community was low. The list of ground rules was the longest I’d ever seen. Finally, we got to a stage where everyone felt “safe enough” and we proceeded.

During the evening of the second day, I reflected on how well the retrospective was going and suddenly realized that many of the ground rules had been broken! The violations were subtle and, during the first day and a half of the retrospective, I hadn’t noticed them. Faced with this realization, I imagined that a number of participants might be wondering why I had not commented on the ground-rule violations.

I decided to discuss the violations the next morning, and to begin to repair any damage that had been done by our disregarding the ground rules. I spent a restless night preparing to salvage what I could.

At the start of the third day, I reviewed the ground rules and asked the group to evaluate how well we were doing in maintaining safety and adhering to our rules. I took a third vote and was surprised by the results. The safety measure had gone up! By the last day, it seemed that the team understood that this was not a witch hunt, but a healthy review of the project. The small violations of ground rules were actually healthy signs that the team was comfortable with the retrospective.

Background and theory: I once asked retrospective participants to tell me what they were afraid of as we started the retrospective. They wrote anonymous notes on index cards and turned them in. Following are comments from individual participants:

• I’m shy in large group settings.

• I don’t negotiate well on the spot. I need time to process. I fear I’m the only one who feels this way.

• Someone might get angry with me for what I say or think.

• I fear I might inadvertently hurt someone’s feelings and damage future working relationships.

• If I express my opinions strongly, I may alienate myself from the team.

• My comments may affect the long-term impressions and perceptions people will have about me.

• The team will think I have a certain attitude.

• People may take offense at something I say. I especially worry when that other person is a manager.

• I fear the consequences for my family of me being fired because I spoke up.

• I fear the group will get sidetracked forever. We are very good at that.

• I fear being blamed for others’ problems—becoming a target.

• My fear is being misunderstood and doing more damage than good to the team.

• I’m afraid of being tagged a candidate for “culling” because of disagreement with the approach being taken by management. If I disagree with the way the team is being built/organized, will I be trusted?

• I fear feeling inept and becoming a source of pain for the team.

• I fear looking stupid and not being taken seriously.

• I fear exposing myself to people I don’t consider to be my friends.

• I fear long-term damage to my personal relationships, which may affect team effectiveness.

The fear people have of speaking the truth during a retrospective is real. However, while the feeling is justified, the actual danger may be far less than people imagine. The facilitator can help group members reduce their fear of speaking the truth by

• acknowledging that the fear is real

• letting people know that they are not alone in having this feeling

• addressing the specific fears

• asking each person to think of ways to establish a safe retrospective

The “Artifacts Contest” Exercise

Course: The Past

Purpose: In this exercise, members of the community use the collection of artifacts from the project to recall events that occurred during the entire life of the project. This activity triggers the process that ultimately will tell the full story of the project. The exercise usually brings out the point that no one person knows everything that went on during the project, and shows people that a retrospective can be fun.

When to use: Once during each retrospective.

Typical duration: One to two hours. (The amount of time needed will depend on how many people attend the retrospective.)

Procedure: The “What Is a Retrospective?” handout discussed in Chapter 5 instructed participants to search for artifacts from their project, and described a contest in which prizes would be awarded to whoever brought the most artifacts, the most unusual artifact, and the most significant artifact. The steps for this exercise follow.

Step 1: Discuss the artifacts. Ask the retrospective archaeologists to share and describe their artifacts. Then, ask them to place the artifacts on the floor in the middle of the room so that everyone can study the collection. For especially mysterious artifacts, encourage discussion of their significance, making sure the full stories are told. Ask questions about the artifacts as they occur to you and invite other people to raise questions, too—these questions, rather than being interruptions, help bring out the full story.

In some cases, I may be the only person who doesn’t know the story, but having it told just for me is not a waste of time. The telling helps everyone in the community think back and remember events with greater clarity.

Step 2: Vote for the artifacts. After all the artifacts have been displayed and discussed, ask the retrospective participants to vote for the winners in the three categories. (I usually suggest that any given archaeologist should be able to win only once.) First identify the largest collection of artifacts, then vote for the most unusual artifact, and, finally, vote for the most significant one—that is, the artifact that is most important to understanding the project. Prizes for the three winners can be bottles of wine, funky hats, funny coffee mugs, or anything else you think will be especially appreciated by the specific community.

Most artifacts are documents. From among the multitudinous possibilities, someone usually produces a collection of all the product-development and delivery schedules, including the first schedule ever produced. If the first schedule is available, I usually ask permission to read it aloud. Invariably, as I read, the community as a body expresses amazement and even a bit of amusement at how optimistic—and naive—it was.

In addition to documents, there are artifacts that are objects. They can range from toys and automobile parts to dried bouquets and defunct computer components.

Throughout this exercise, the collection of artifacts piled on the floor grows. I am always impressed by the accomplishments these tokens represent, but participants in a retrospective also seem in awe when they see how much has been accomplished. As the exercise ends, I ask community members to quietly study the collection and reflect on all that it represents.

Step 3: Have the community arrange the artifacts and ask volunteers to take a few photographs. Save the photographs to post on the bulletin board or lay them out on a display table for future discussion.

Step 4: Collect the artifacts. To end this exercise, ask everyone to place the collected artifacts on a table that has been set up at the side of the room. Mention again that the artifacts represent valuable information, and suggest that people refer to specific artifacts throughout the retrospective for clarification or confirmation of project facts.

A True Story

Once, during the opening minutes of an “Artifacts Contest” Exercise, a contract programmer who had joined the project during the coding phase held up a notebook and claimed that it represented her nomination for “most significant artifact.” She explained that because she usually joins projects late in the development cycle, she needs to be able to do her job without allocating any significant amount of time to learning about the project. She gets up to speed by understanding just the part of the system for which she will write code.

Holding up the notebook, she said, “This is the first project on which I’ve ever truly understood the whole system. It’s because of this project notebook. It is complete, consistent, coherent, and correct. My nomination for ‘most significant artifact’ is not really this notebook, but its author—Michelle, our technical writer!”

As the contract programmer finished speaking, the room erupted in applause. Although Michelle had been assigned to the project full-time to keep the project records as well as to develop the users’ manual, she had done much more for the project than perform just those two tasks. Her ability to find inconsistencies in the records and her tendency to keep asking questions until she understood the system caused the whole team to think, reflect, and rework.

When the votes came in, Michelle was named the team’s most significant artifact, possibly making this retrospective the first time in history that a group of archaeologists considered a living human being to be their most precious artifact! (It might also have been the first time in history that a technical writer was recognized for what he or she contributed to a project!)

Background and theory: At the end of a yearlong or multiyear project, most team members clearly remember only the last few months of work. They need to think about and review the entire project before the retrospective begins. In truth, asking people to think back over the life of their project results in very little thoughtful recollection. However, the search for artifacts provides structure, and encourages people to think without the facilitator ever mentioning review as a goal. The artifacts search provides an unusual and fun way to stimulate important memories.

Making participants aware—in advance—of each of the three awards has its own purpose:

• Knowledge of a prize for “most artifacts” causes people to review all the documents that exist and thereby encourages them to think about the entire project. It also ensures that the group will have the documents needed during the retrospective.

• Knowledge of the award for “most unusual artifact” causes people to think about the project in creative ways and encourages them to develop meaningful stories about the unusual artifacts they are considering.

• Awareness of the “most significant artifact” category causes people to ask themselves what was most important during the project.

The collection of artifacts provides a way to ease participants into review of the project. Presentation of the artifacts establishes an atmosphere of fun and celebration. As the artifacts are discussed, participants realize that many events occurred without their awareness. This realization arouses a curiosity that usually carries into subsequent exercises. Since curiosity is a key to learning, this is a valuable exercise.

An additional benefit lies in the fact that the community itself votes on the awards, demonstrating that the team (not the facilitator) is in the position of deciding what is and what is not important.

References for Further Reading

Knowles, Malcolm. The Adult Learner, A Neglected Species, 4th ed. Houston: Gulf Publishing, 1990 (pp. 27–65).

Knowles provides a theoretical basis for the “Artifacts Contest” Exercise in this study, which investigates the way adults learn.

Shaffer, Carolyn R., and Kristin Anundsen. Creating Community Anywhere. New York: Jeremy P. Thurcher/Perigee Books, The Putnam Publishing Group, 1993 (pp. 305–19).

In this book, the telling of stories and the sharing of artifacts builds a community through a common experience.

Sawyer, Ruth. The Way of the Storyteller. New York: Penguin Books, 1942.

The power of storytelling as a time-tested way of learning and sharing experiences.

The “Develop a Time Line” Exercise

Course: The Past

Purpose: Building a time line allows each participant to add pieces to the collective story of the project. This exercise helps team members understand all that occurred during the project and enables them to build a disciplined framework for looking at the entire project in order to find the lessons that need to be learned.

When to use: Always.

Typical duration: Five to eight hours. (Spread this exercise over two days so that there is a night between for reflection.)

Procedure: This exercise is composed of two activities—the first is geared to building the time line, and the second, to mining the time line for gold.

Step 1: Prepare the room. First, cover one long wall with two rows of 36-inch-wide butcher paper. Make each row 30 to 60 feet long—the length will be determined by group size, project length, and available wall space. Divide the paper into meaningful time periods, moving chronologically from left to right. For example, for an 18-month project, time could be divided into quarters; for a half-year project, into six separate months.

Step 2: Ask community members to move into their natural-affinity groups. Once the groups are established, pass out a package of index cards to each group, along with marker pens. Each natural-affinity group should have its own color of pen.

Instruct each person to write his or her name on an index card, followed by the date he or she joined the project. If anyone participating in the retrospective left the project before it was completed, have that person make a second card stating name and departure date. Next, ask people to make cards for anyone missing from their team, giving specific names and start or departure dates. Explain how the time line works and ask people to tape their cards at the very top of the time line within the appropriate time period.

Step 3: Identify significant events. Ask each natural-affinity group to find a private space where people can work without interruption. Their task now is to identify significant events that occurred during the project, noting one event, with its dates, per card. Stress that this is not a consensus activity but rather is an inclusive activity. That is, anyone who thinks an event was important or significant should create a card for it.

Before groups begin the work assignment, ask people to look over their artifacts and take with them any artifacts that might help with this exercise.

Generating events cards often takes people quite a bit of time, because they find a great deal to discuss about the significant events. This period of reflection and remembering is an important benefit of preparing the cards. Allow one to two hours for this step.

Step 4: Reassemble the entire community. At the end of the allocated time, direct people to tape their date-bearing events cards on the wall-chart segment that corresponds to the correct time period. (When I started using this exercise, I tried to establish an orderly way of putting the cards up, but the participants always seemed to make it a free-for-all. Later, I realized that this unstructured session allows participants to post their cards anonymously. Now, I hand out many rolls of tape and tell everyone to “have at it.”)

Step 5: Invite people to walk along the time line to see what strikes them. A special moment of learning happens after the time line has been completed. People are fascinated to see what they have created. Often, I need only announce a long coffee break and people begin walking along the time line on their own. Sometimes, I’ll suggest, “Grab some paper and record your impressions.” Some people study the time line individually, while others form groups to discuss their observations. Both approaches are fine; they just demonstrate differences in learning preferences.

Step 6: Leave the time line for a bit. You can expect the community to be tired at this point; it might be late in the afternoon of the first day or approaching lunch on the second day. A respite of some kind is in order. If a break is scheduled, adjourn until the next meeting time. If a break is not timely, shift into another exercise and return when the community is rested. I usually consider using the “Offer Appreciations” Exercise or a form of the “Repair Damage Through Play” Exercise (both are discussed in this chapter). Return and begin the “Mining the Time Line for Gold” activity after the community has had some rest.

Mining the Time Line for Gold

This second portion of the time-line exercise provides participants with a significant opportunity for learning because it forces a review of the project from a big-picture perspective. The time line depicts events deemed important from everyone’s point of view; by mining it, people review the project, period by period, to see what associations, patterns, or anomalies can be discovered. The “gold” is the understanding that comes to group members as they look at the time line and discover they can learn more by working together than any one individual could have learned on his or her own.

Step 7: Put five flip charts on easels located around the room. Explain to the community, “This is where we will place our gold as we mine the time line. Each flip chart will contain a different kind of nugget.” I label the flip charts with the following topic headlines:

• What worked well that we don’t want to forget

• What we learned

• What we should do differently next time

• What still puzzles us

• What we need to discuss in greater detail

I use these five topics to help focus discussions as the time line is mined. Most of these topics are self-explanatory, but a few need elaboration.

The what-worked-well-that-we-don’t-want-to-forget topic is phrased in a very particular way. Simply asking for what worked well can turn into a long list of motherhood-and-apple-pie statements. I’m looking for just those things that are at risk of being lost.

The what-still-puzzles-us topic encourages honest discussion about what the team doesn’t know how to do. Such discussion often leads to training, invention, research, and discovery during the next project.

The what-we-need-to-discuss-in-greater-detail topic is used to keep the retrospective moving. During a discussion, if closure seems difficult, it is usually because the subject matter is complex and involves the melding of a number of viewpoints. I add the topic to the flip chart, explaining that we will return to it later in the retrospective.

One clear benefit of listing these last two topics is that they serve as a bridge from one course of our retrospective meal to the next—the activity of specifying puzzles from the past and identifying complex issues needing further discussion leads to planning for the future.

Step 8: Ask volunteers from the community to serve as recorders. Assign one volunteer to each flip chart. I delegate this task to volunteers rather than handling it myself because no one person can facilitate well and also act as scribe.

Step 9: Examine each time period in chronological sequence. To help people identify critical events, ask a variety of questions, such as

• What card jumps out at you as the most significant?

• What card surprises you?

• What card or cards don’t you understand?

• Do you see any patterns emerging as you compare cards?

• What card should we discuss next?

• Is there another card suggesting this topic but from a different point of view?

• What card still needs discussion?

Use these questions to stimulate discussion. Once started, let the dialogue take its natural course but guide the discussion to formulate statements that can be written on one of the flip charts.

A True Story

During the closing hours of one retrospective, the group’s vice president of software development visited us. His curiosity about the retrospective was refreshing, and although I gathered that the cost of the retrospective was a serious expense for him, he was most supportive and willing to help in any way he could.

As team members explained what they had accomplished during the three days, the VP became especially interested in the time line. He asked what would happen to it when we finished. Since we had already mined all the gold, I told him that we would probably throw it away. “No, please don’t. I need it!” he replied. He went on to explain that his field was not software but water-distribution engineering (the firm produced software to control large water-flow systems). He said he had never realized how complex a software project was. The retrospective time line made it clear.

“Next week, some of my people will be making a pitch to our Board of Directors, hoping to establish a software-engineering process group. Frankly, I haven’t been able to support them. I didn’t understand why it was important. I want this time line in the boardroom. It communicates instantly what goes on in our company. It’s real-life, not theory. This shows me that building professional software is much more complicated than what we were taught in my college courses. Now I finally understand why we need a software-process group.”

The time line was installed in the corporate boardroom and remained for nearly a year. I gather it was the stimulus for many useful discussions about the discipline of building software, using terms that describe the way engineers control water.

The “Emotions Seismograph” Exercise

Course: The Past

Purpose: On some projects, events cause unexpected changes in emotions. In this exercise, which is adapted from one I learned from my colleagues Jean McLendon and Eileen Strider, we explore the events that trigger emotional reactions. Our goal is to build better understanding.

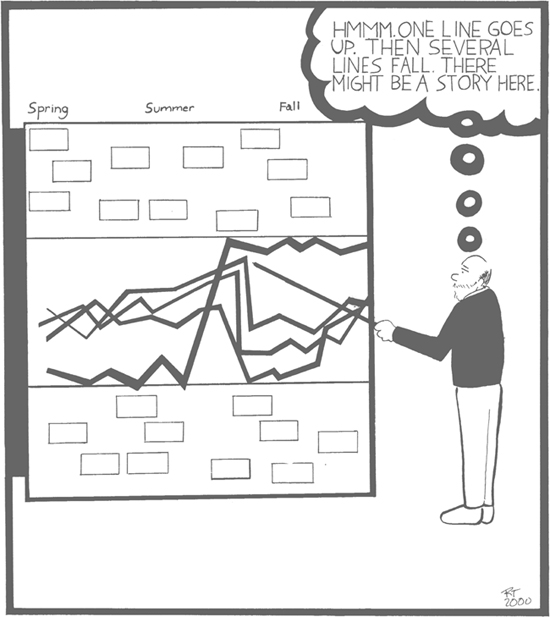

When to use: I use this exercise on occasions when information submitted as pre-work indicates that there were numerous changes made during the project, and the people who made them (possibly the managers) didn’t appreciate the impact those changes would have on the emotional health of the community. A fellow facilitator, Esther Derby, always uses the seismograph as part of the “Develop a Time Line” Exercise. For her, the seismograph is the key guide during the “Mining the Time Line for Gold” activity.

There are several points at which you might ask the community to draw a seismograph: For example, you might suggest this exercise after the group has had time to reflect on the time line, or perhaps at the beginning of the next day, or even at the end of the “Mining the Time Line for Gold” activity. I’d like to be more precise, but it is a decision based in large part on intuition.

Typical duration: One to two hours.

Procedure: This exercise uses the developing time line, and can be executed concurrently with the “Develop a Time Line” Exercise.

Step 1: Modify the time line. Draw two parallel, horizontal lines, one foot apart on the butcher paper taped to the wall. These lines should be drawn to form a band running from left to right near the middle of the paper. During the “Building the Time Line” activity, the Step 4 instruction to community members to tape their events cards outside of the middle band, either above or below.

Step 2: Ask people to walk along the time line from left to right, reading the cards and drawing a continuous line in the middle band area. The line should rise and fall to reflect the feelings individuals had during the project at the time noted on the cards taped above. I usually explain the scale by saying, “A line within the top area of the band means ‘This job is great! I can’t wait to get to work.’ One at the bottom means, ‘I hate my job.’ A line drawn in the middle means ‘Hey, it’s a job.’” Make sure each person uses the color marker pen that others in the same natural-affinity group are using.

The wording you use to give directions should be compatible with the cultural preferences of the group. Some groups are not comfortable talking about their feelings; others see a discussion of feelings as a natural part of their work. Depending on the group, I might ask people to rate either their “job satisfaction” or “the intensity of their feelings,” or I might just say, “Mark what was going on for you at that point in time.”

Just as you did in the “Building the Time Line” activity of the “Develop a Time Line” Exercise, tell the group to “have at it.” Make sure this moment is a bit chaotic to assure a degree of privacy for anyone who wishes it.

Step 3: Help participants interpret the seismograph. To guide the interpretation of the seismograph, you have two choices. Either you can ask the community “What do you make of this?” and allow people to select points in time that they want to discuss, or you can note interesting trends and ask people to discuss them.

Background and theory: It is hard to initiate a discussion of feelings in the workplace, but once started, comments seem to flow easily. This exercise is designed to slowly move the community into that discussion. The seismograph allows feelings to stay private but shows—by the color of marker pen—whether various members of each natural-affinity group experienced the same feelings.

The discussion of feelings shows team members that they are not alone. It also gives them a way to talk in terms of the group’s feelings while really discussing their own. As the discussion proceeds, individuals can shift from talking about the group’s emotions to talking about their own.

The “Offer Appreciations” Exercise

Course: The Past

Purpose: This exercise provides an opportunity to give recognition to everyone who deserves it. On every project, there are heroes. In fact, usually everyone on the team performs some heroic act, at one time or another, that helps get the software out the door. However, as a culture, we seem to have lost the inclination to give someone a “high five” or say “great job!” As a result, individuals who singly or collectively perform great feats of heroic behavior remain unappreciated.

When to use: Use this exercise to take a break from the “Develop a Time Line” Exercise, at the end of the day when everyone is tired, or when something happens in the retrospective that suggests the community could benefit from this exercise (for example, you could introduce the exercise when you notice a few people sneaking in compliments during one of the other exercises). I use this exercise in about half of the retrospectives I facilitate.

Typical duration: One hour.

Procedure: Start this exercise by asking people to contribute to a definition of the word “hero.” I usually look for a definition indicating some or all of the following characteristics:

A HERO IS... One who is endowed with great courage and strength, who is celebrated for bold exploits, and who is favored by the gods. ...One who is noted for feats of courage, especially one who has risked or sacrificed his or her life. ...One who is noted for special achievement in a particular field. ...One who has discovered and shared new knowledge, understanding, or inventions.

Ask whether there were any heroes on the project. You will usually get a few nods. Discuss the fact that the phrase “great job!” is rarely spoken in our business, and then explain the exercise by saying, “You see hero worship and recognition of achievement all the time in the sports world. The fact is, giving a compliment feels great, and doesn’t cost anything. On this project, everyone has had to do something significant to get the product out the door—and everyone needs to be acknowledged for that. I’d like this group to try the ‘Offer Appreciations’ Exercise. This is how it works: Someone who has an appreciation for another person will start off as ‘It.’ The person who is ‘It’ selects a hero, says the hero’s name, and gives the appreciation. The message must be in the form of ‘Tom, I appreciate you for...’”

Often, people will try to change the phrase into “I appreciate Tom for...” This use of the person’s name as the object of the verb does not have the same impact as does direct salutatory address—so, interrupt and help the speaker rephrase the message.

For some people, it is very hard to receive a compliment. Encourage them to just listen to the message. If they want to say “thank you,” that’s fine, but they need not say anything else.

Once the appreciation has been delivered, the receiver of the appreciation is now ‘It’ and can offer an appreciation to someone else. This goes on until everyone has been the receiver at least once.

End this exercise by observing that it really does feel good to receive “appreciations.” Giving one is a gift that costs nothing and means so much to the receiver. I tell the group that each of us is likely to think of more appreciations over the course of the retrospective as well as after our gathering. I encourage group members to share their appreciations as they come up. Then, I suggest that offering appreciations might be a good thing to add as an ongoing daily practice so that it becomes part of the group’s culture.

As described in Chapter 2, there are times when a manager wants to give an appreciation to everyone. If this happens, let it. It would be unfair and unwise to restrict a manager to an appreciation of only one person. Occasionally, I change the exercise to let people volunteer appreciations as they feel the need. The “It” game is used to get things started, but it can be adapted to fit the mood of the retrospective.

Theory and background: The fundamental goal of a retrospective is change. Virginia Satir studied how to help groups change and developed a six-phase model that includes making contact, validating, creating awareness, promoting acceptance, making changes, and reinforcing changes.

The second phase—validating a person’s self worth and willingness to consider the possibility of change—is built upon a foundation of offering a person honest expressions of appreciation. That is, appreciation for what the person has accomplished, what he or she has contributed or knows, or simply for who he or she is.

References for Further Reading

Loeschen, Sharon. The Magic of Satir: Collected Sayings of Virginia Satir. Long Beach, Calif.: Event Horizon Press, 1991 (pp. 7–15).

Loeschen provides an insightful discussion of Satir’s use of appreciation in this inspiring collection. My entire work on retrospective rituals could have been derived from the Satir Change Cycle described in Loeschen’s book.

The “Passive Analogy” Exercise

Course: The Past

Purpose: This exercise is designed to help people learn about their project by encouraging them to relax and let their minds wander while they enjoy a movie. The activity should be structured to offer entertainment that both provides parallels with the team’s project and that enables group members to view the project from a different perspective.

When to use: I save this exercise for residential retrospectives. It fits best on the evening of the first day. It usually follows the “Building the Time Line” activity.

Typical duration: Two and one-half hours to watch the movie, with an additional one to two hours for discussion on the following morning, depending on the community’s needs.

Procedure: Find a casual setting for community members to use that’s different from their regular workspace. A room with a large-screen TV/VCR set-up, comfortable couches, and over-stuffed chairs would be a good choice. Arrange to have snack food and soft drinks available.

Choose the movie that you feel most closely parallels the project you are facilitating. I almost always choose Flight of the Phoenix, featuring Jimmy Stewart and three co-stars. The plot of this movie, which revolves around the reassembling of a plane from scattered pieces of wreckage after a crash, provides an excellent analogy for most software projects.

Before showing the movie, instruct people to watch it while keeping in mind the context of their own project. At the end of the movie, ask everyone to consider questions such as the following for discussion the next day.

• How were events in this movie similar to those in your project? How were they different?

• What mistakes did the characters make that you avoided? How did your project avoid them?

• What did the movie characters do that you wish had been done on your project? How could their success have been experienced on your project?

• With whom in the movie did you most closely identify? Why?

By allowing people to “sleep” on these questions, you afford them the opportunity to process their ideas subconsciously. For many people, powerful insights come while they sleep.

To start the morning session on the next day, open the floor to a discussion of the questions. Use discussion of the next-to-last—which characters did people most identify with?—to set up the morning’s final activity before lunch. People usually mention four characters after viewing Flight of the Phoenix. For the final activity, ask the participants to move into groups, one for each of the identified characters. Direct all who identified with the pilot in Flight, for example, to move to one corner of the room, those who identified with the character of the navigator, to a second corner, and so on. Next, give all four groups the same assignment, designed to help them uncover preferences in their problem-solving styles. Choose the assignment according to what you learned from the pre-work handout. Here is an example:

Think about what mistake your character made with which you have some personal experience. Did others in your group make this same type of mistake? Discuss how you can prevent such mistakes from occurring during future projects. Once you have identified a pattern, select a representative to report back to the whole community on your group’s discussion and/or discovery.

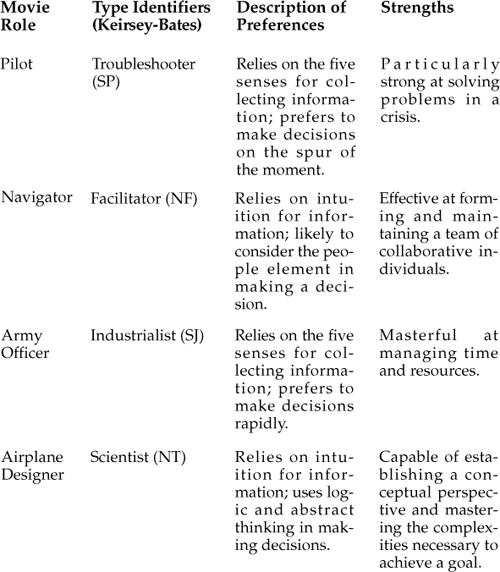

Background and theory: In Flight of the Phoenix, the four main characters typify problem-solving behaviors that correspond to the four temperament types in Keirsey-Bates theory. That is, people have certain preferences in the way they work to solve problems. Fundamental to Keirsey-Bates theory is the premise that people must learn to appreciate both their own preferences and also the preferences of others who use different problem-solving approaches. Through understanding of these differences, teams can preserve their diversity while still honoring the preferences of others and taking advantage of their strengths. The following chart identifies the temperament type of each of the four characters in the movie and describes problem-solving styles.

If participants are not familiar with type identification, summarize the technique in your own words but make available reference copies of the six books listed in the following “References for Further Reading.” Do not insist on use of exact Keirsey-Bates terms but rather help people understand and verbalize their preferences. By asking people to select the character they most identify with, you help them articulate their temperament types and preferences. At this point in the exercise, you should be sure everyone in the group has a clear understanding of type differences. Guide type identification by asking questions such as the following:

• How did your character contribute to the team in a positive way?

• What weaknesses did your character have?

• What didn’t your character appreciate in each of the other characters?

• What should your character have done differently?

• How do your answers reveal opportunities to change, modify, or preserve the way you function at work?

References for Further Reading

Keirsey, David, and Marilyn Bates. Please Understand Me: Character & Temperament Types, 4th ed. Del Mar, Calif.: Prometheus Nemesis Book Co., 1984.

Type preference theory is a powerful facilitator’s tool, and it is clearly presented in this excellent work. We revisit this material in conjunction with the exercises detailed in Chapter 9.

Myers, I.B. Gifts Differing. Palo Alto, Calif.: Consulting Psychologists Press, 1980.

This is the seminal work and should be read by all facilitators.

Weinberg, Gerald M. Quality Software Management, Volumes 1–4. New York: Dorset House Publishing, 1992–1997.

The Weinberg series provides much that is valuable on types and temperaments. See especially Appendix F in Volume 4, which gives a concise but clear summary.

The “Session Without Managers” Exercise

Course: The Past

Purpose: The purpose of this exercise is to help workers learn how to express their opinions honestly when they talk to management. In some environments, there is an “us versus them” attitude dividing managers from workers. Workers fear reprisal if they tell a manager what they think. Participants from such an environment are likely to begin the retrospective feeling oppressed and powerless. If you believe this to be the case from your review of the “Retrospective Pre-work Handout” or from initial interviews with project members prior to the start of the retrospective, then this exercise is a possibility.

When to use: I use this exercise infrequently and only when project members have tried to establish a safe retrospective environment, but have been unable to do so. The “Session Without Managers” Exercise is especially useful when the managers indicate that they want to hear what their workers have to say, but are frustrated because their people either don’t communicate or communicate ineffectively. By holding the “Session Without Managers” Exercise, you encourage healthy dialogue. (If I have determined during the retrospective-preparation stage that the managers are not interested in such a dialogue, I generally decline to hold the retrospective at all!)

Schedule this exercise to be given after the “Develop a Time Line” Exercise but before any of the exercises that belong to the Future course. While various issues will arise during the time-line activities, this exercise will help identify the few sensitive issues that are not explored during the “Mining the Time Line for Gold” activity.

Typical duration: Two to three hours, depending on the magnitude of the problem, the amount of instruction you need to provide, and how complex a message is developed during the exercise.

Background and theory: When workers are afraid to tell managers what they think despite the fact that managers want the feedback, there may be a variety of dynamics at work.

Reluctance to speak freely may result from a worker’s painful experiences with past managers. People who have picked up coping habits from previous work situations may carry those habits unknowingly into new relationships, even though the behavior is no longer needed.

A second dynamic may be a worker’s perception that the manager is playing the same role as an authority figure from his or her childhood: a parent, a teacher, or a school principal, for example. In this situation, the worker may use response tactics learned as a child. You might see such a person exhibit childlike behavior, such as becoming tongue-tied or uncharacteristically quiet; or the person may exhibit fast, shallow breathing or show a marked change in posture.

Conversely, responsibility for a lack of communication may lie with the manager who may have responded to feedback in the past in a way that discouraged future input. Perhaps the manager frequently interrupted the worker to point out that something was wrong, or perhaps the same manager failed to respond in any way to the worker’s input. Both scenarios can be fatal to open communication, but they do happen. Managers have a different perspective on the project and the company than workers have; they experience different pressures and difficulties, and they function in a world of budgets, office politics, and customer relations. Workers exist in a world of directives, schedules, and deadlines. Because both groups see events from such different viewpoints, either group may dismiss the other’s message as invalid.

Another dynamic barring effective communication may be a manager’s belief that he or she, as a leader, must have a solution to every problem. This expectation leads either to quick-fix solutions or to explanations of why things can’t change. Both of these reactions prevent people from really listening to other people’s ideas.

If any of these dynamics exist, they need to be addressed during this exercise. The key to opening channels for communication is helping the manager to understand that workers usually do want to be heard and that they don’t expect all problems to be fixed.

Procedure: Send the managers off to meet with each other to consider everything they have heard so far. Ask them to develop a statement summarizing their view of what happened on the project and specifying what they believe should be done differently next time. Remain with the group of non-managers, and work with them to develop a similar message to managers. If there are two facilitators, the second one should work with the managers. Do not divide the group of non-managers into two groups as you want a single message or statement to be developed.

Step 1: Check safety. Once the managers have separated from the workers, perform a quick safety-check to see whether the workers once again feel safe enough to discuss issues. You may have to get everyone to agree that what is said in this meeting stays in this meeting.

Step 2: Direct the workers to develop a message for their managers. The workers’ message is to follow a specific format:

• The message should not be a list of complaints. It might start as that, but every negative issue raised needs to be paired with a positive recommendation.

• The message should explain why its authors believe this can be a “win-win” situation for all involved, indicating they’ve made every effort to see the problem from the managers’ side as well as from their own side.

• The message must communicate a strong commitment to helping the managers do a better job.

• The message needs to show that the workers are ready to share in the responsibility of moving with the managers toward the solution.

As facilitator, your role is to empower the workers to speak for themselves. Resist intervening unless people are no longer making progress. If you do need to take the lead, try to yield that job to the first capable person who appears to be moving into a leadership role.

Be prepared to help non-managers reshape conflicting, incongruent messages into congruent, harmonious ones. Try to do this from a collaborator’s position rather than from a facilitator’s position.

Step 3: Reassemble everyone once the managers and the workers have both developed their messages. I use the following approach for delivery of the two messages.

• First, instruct workers to deliver their message completely. Managers can ask questions related to clarifying the message, but they cannot comment on it until the message has been completely delivered.

• Next, ask managers to comment on the message, either immediately or at a later, mutually agreeable time. If at all possible, they should communicate their response during the retrospective so that you, as the facilitator, can guide the exchange.

• Then, give managers the opportunity to deliver their message. Workers can ask questions related to understanding the message, but, like the managers, they cannot comment on it until the message has been completely delivered.

• Finally, encourage workers to respond to the managers’ message.

As facilitator, I prefer to have one or more workers deliver the message to the managers; I agree to serve as spokesperson only as a last resort. My reason for staying away from this role is that I don’t have the context of experiences shared by the people on the project, and therefore cannot explain the message as well as they can. If no worker feels safe enough to deliver the message, I preview the content with the workers, asking them to provide verbal context and detailed explanation. Whoever seems most able to help me with the explanation usually becomes the person I will eventually ask to take over for me (again, my goal is to empower the workers).

A final note: The cartoon near the beginning of this exercise suggests an unpleasant situation. A workplace in which managers and workers are not in continuous effective dialogue is not a healthy one. The “Session Without Managers” Exercise provides a stepping-stone toward helping the community find a better way of working. Whenever this exercise has proven necessary, I follow it up with a worker-management communication-improvement activity in the Future course, usually as an item to be broached in the “Cross-Affinity Teams” Exercise.

References for Further Reading

Satir, Virginia. The New Peoplemaking. Palo Alto, Calif.: Science and Behavior Books, 1988.

Written for lay people, Satir’s work provides a good introduction to the topics of communication stances and rules. See especially Chapters 6 through 9.

Satir, Virginia. The Satir Model: Family Therapy and Beyond. Palo Alto, Calif.: Science and Behavior Books, 1991.

This book is intended for professionals in the field of therapy, but it can be quite enlightening to facilitators. Chapters 3 and 4 treat stances and congruence in greater detail than the topics are treated in The New Peoplemaking.

Seashore, Charles N., Edith Whitfield Seashore, and Gerald M. Weinberg. What Did You Say? The Art of Giving and Receiving Feedback. Columbia, Md.: Bingham House Books, 1991.

Now available directly from the authors—see www.geraldmweinberg.com for details—this compelling book explores the art of giving and receiving feedback, presenting the theory upon which the “Session Without Managers” Exercise is designed.

The “Repair Damage Through Play” Exercise

Course: The Past

Purpose: During a project’s final days, everyone experiences a great deal of stress, and relationships between workers may become damaged. This exercise is designed to repair that damage by creating opportunities for people to play together. Playing time gives all participants a chance to release tension and to reflect on what they have discovered during the retrospective.

When to use: Daily, up to several times a day for residential retrospectives. It is effective to use evenings, after lunch, or whenever the community needs a break.

Typical duration: One hour or longer.

Procedure: This exercise is not one specific activity, but rather includes a variety of activities held as needed throughout the retrospective. The events range from unstructured, informal activities to well-organized games. I like to include both.

For unstructured activities, I give directions such as, “All of you have been indoors too long. Take your natural-affinity team outside and find something to do. Don’t talk about the project for at least thirty minutes. Let’s reconvene in an hour.”

Group members might go for a walk, take a bike ride, or simply sit on a park bench. They might explore the neighborhood, practice juggling, or just watch the clouds float by.

Structured activities usually involve playing games with rules, requiring people to interact with each other. Games afford opportunities for people to team up, either within natural-affinity groups or as non-affinity groups of people who don’t usually work together. Activities can range from pool, Ping-Pong, and poker, to touch football, tennis, or Pictionary. I ask members of the community to plan these structured, recreational activities because people tend to benefit more from recreational activities they’ve chosen than from activities assigned to them.

The process of working together to prepare food also provides an important bonding experience. People who plan, shop for, and cook out at a barbecue, for example, can become better teammates. Active participation in the preparation of a shared meal generally builds powerful team connections.

To motivate people’s participation in structured “play” activities, I bring to each retrospective an old trophy that I usually have been able to find at a flea market or in a consignment shop. To illustrate that this trophy is special, I tell some story that is too crazy to be believed, but which contributes to making the trophy prized by members of the community. Teams compete for the trophy in a variety of activities so that all individuals have the chance to demonstrate their particular skills. When I award the trophy, I explain, “This trophy is to become a continuous-challenge trophy, with the rules to be defined by you.” I give some examples of how people can continue to use the trophy on future projects, such as competing for the trophy only at the end of projects or only in sports that they have never played together before—the sillier the better.

Background and theory: When a team goes through difficult times on a project, no one enjoys the experience. Stress and tension are high, and people behave uncharacteristically. In such circumstances, it’s easy for team members to dislike the experience so much that they will decide to leave the team. However, a community that plays together will form special bonds. The relationships built around these play-filled times help individuals find new reserves of strength and patience to carry them through the hard times.

If you are facilitating a retrospective for a team whose members are already in the habit of playing, then this exercise provides a good opportunity for them to further strengthen their relationship. Through play, damage that occurred from end-of-project stress begins to repair itself. People see each other as individuals rather than just as barriers to progress or as reminders of problems.

The “Cross-Affinity Teams” Exercise

Course: The Future

Purpose: In the “Mining the Time Line for Gold” activity of the “Develop a Time Line” Exercise, issues were identified that required further discussion. In most cases, these issues will have emerged from a variety of viewpoints, usually representing the specific orientation or interest of the separate natural-affinity teams. In the time-line exercise, the community also identified topics that were puzzling. This “Cross-Affinity Teams” Exercise is used to further those discussions, by breaking the community into different subgroups. The goal is to identify better ways to direct the next project.

When to use: Always.

Typical duration: Five to six hours.

Procedure: This exercise uses two of the five flip charts created in the “Develop a Time Line” Exercise. Pick the charts labeled “What still puzzles us” and “What we need to discuss in greater detail.”

Step 1: With the community, review the topics listed on the two flip charts. Ask people to help you clarify, organize, and consolidate entries; then list the issues in order of priority. Identify the three or four issues that people agree most need to be discussed at this point in the retrospective.

Step 2: Build teams consisting of at least one member from each natural-affinity group. These cross-affinity teams will be assigned responsibility for exploring one of the three or four issues identified above.