Chapter Three. Engineering a Retrospective: Making Choices

After many years of toil, Ant decided it was time to get out of the old digs and buy a new place to live. He looked for an agent and found the perfect one at Busy Bee Realtors—Busy Bee himself. Not only was Bee’s work ethic identical to Ant’s, but Bee had experienced communal living and understood what his client wanted.

After assuring Ant that he would be able to find him the perfect home in no time, Bee flew off to start the search. Within minutes, Bee returned, full of details of a newly built condominium with a great view. He said that the current tenants were upscale and high-energy, just like Ant, and that the community association was very active, with every member working in harmony. Bee said it was so perfect, in fact, that were he not Ant’s realtor, he would have bought it for himself.

Bee went on to explain that the condo was located several hundred yards away and told Ant that an offer should be made as soon as possible. Ant knew it could take him days to travel the distance, and trusting Bee’s word, agreed to buy the condominium sight unseen. The papers were signed, the deed transferred, and Bee and Ant set a time to meet at the condominium.

Quite eager to see his new home, Ant set off on his journey at break-antenna speed. Realizing he had arrived well before the time that he and Bee had agreed to meet and unable to contain his excitement, Ant decided to tour the new condo on his own. As he approached his new home, however, Ant was shocked to discover that Bee had sold him space in a beehive—the condo was a waxy, six-sided affair without a single tunnel! After just a few minutes, Ant found that the neighbors’ humming had gotten on his nerves, and that the temptation to sample the honey was overpowering, even though sampling was clearly against the association rules.

Bee arrived at the appointed time to find Ant irate and agitated. Even after learning what Ant objected to, Bee could not believe that the condo was not a perfect fit. In his mind, this condo had everything. . . .

[As this is a fable, fair reader, you may trust that insect attorneys got the mess straightened out eventually, but Bee was rather shaken by the whole experience. Here is what happened next.]

Bee went to Owl to see what he could learn. After intense discussion, Owl and Bee concluded that Bee had failed to understand a basic truth: One size does not fit all. The perfect fit for one type of client may be entirely wrong for another. Bee decided that he needed to better understand what his clients wanted, and to control his enthusiasm for what he himself considered desirable.

Watching Bee fly off, Owl congratulated himself, “Now, that retrospective went well. I think Bee learned something.” He blinked rapidly for several seconds and then glanced downward as a rather forlorn and exhausted ant started to climb his tree.

The design principle of a beehive is that one size fits all. Once you have the perfect form, you need only replicate it and everyone will be happy. But Bee discovered that “one size does not fit all”—and this fact is true for retrospectives as well.

Bee’s experience leads me to make two important observations about how to engineer retrospectives:

1) It is much easier to copy the format of a previous retrospective than to design one for a new situation, but used retrospective plans are not likely to fit well.

2) Each retrospective needs to be engineered to fit its unique environmental conditions and team dynamics.

In the most fundamental sense, we “engineer” retrospectives. Webster’s Ninth New Collegiate Dictionary defines the verb “engineer” as “to contrive or plan out usually with more or less subtle skill and craft,” or, “to guide the course of.” The following sections discuss this concept in greater detail.

Engineering a Retrospective

Although each retrospective needs to be uniquely tailored to the situation at hand, there are some common choices I have to make when I begin designing any new retrospective. In making these choices, I match my facilitator skills, experience, tools, and exercises to the particular environment and team dynamics. By environment and team dynamics, I mean the project, the people, the events that occurred during the project, the outcome, the attitudes, the objectives for the future, and so on. While the list of choices I need to make is the same, my decisions are always different, based on the various circumstances I need to take into account.

First Consideration: What is the purpose of this retrospective?

When I’m first contacted to help a team perform a retrospective, I always ask, “Why do you want it?” Usually, the question catches the prospective customer off guard. I get answers such as, “Because it was suggested during our last CMM audit.” “Because it is part of our corporate ISO 9000 process.” “Because we heard it was good to do.” and “Hey, you’re supposed to be the expert—don’t you know?” Yes, actually, I do know a number of reasons to perform a retrospective, and most are better than those listed above.

At this point in the planning stage, I need to understand what will be accomplished by holding this retrospective. I try to find out for whom the learning is intended—management, developers, or the whole team?

Each organization has different retrospective goals, and until those are understood, I can’t engineer a retrospective that will meet the team’s needs. Likewise, team members won’t know if the retrospective has been successful unless they know what their goals were. A comment such as “You’re the expert—don’t you know?” reveals something important—that the organization doesn’t know what it wants from a retrospective.

To uncover the real goals, I usually need to speak with a number of people from the project. I often start by saying, “Tell me about the project—just the really important stuff.” After hearing a number of responses, I begin to see what the organization wants to accomplish with the retrospective. I then explore possible goals with the client.

Possible Goal # 1: Capture effort data. This goal quantifies the actual effort expended on the project. The end of the project is a perfect time to collect and record meaningful project data.

Possible Goal # 2: Get the story out. During any multi-person project, a number of events occur that aren’t known by the whole group. In fact, on most projects, no one person knows all the stories, and no one person knows how the pieces fit together to tell the tale of the entire project. The whole story needs to be told in a forum in which everyone can contribute. It is the act of telling the story that eliminates the need for participants to waste time grumbling at the lunch table for months to come. It is a way to put into context the situations that, by themselves, may seem inconsequential, and a way to discover heroic acts that went mostly unobserved. In short, telling the story allows the whole group to understand exactly what happened and why.

Possible Goal # 3: Improve upon the process, procedures, management, and culture. By reflecting on what has occurred, we see things that we might do differently (and hopefully better) the next time around. And—just as important—we also discover what we did well and don’t want to forget. When we reflect as a community rather than as individuals, the learning is greater. We see the whole, not just our individual piece.

Occasionally, this goal may get expressed as, “We need to fix Chris.” Such a statement is usually accompanied by an explanation of what Chris did or didn’t do and why the whole project failed because of Chris. Whenever I have looked more deeply into the “fix Chris” situation, I have discovered many issues for the whole team to work on improving, and Chris is only one part of the team’s problem.

Possible Goal # 4: Capture collective wisdom. There are many firms that build teams for each project, rather than organize projects around an existing, long-term group. In this situation, the collective team wisdom acquired during the previous project is likely to be lost as individuals are scattered across the organization to support new undertakings. If, at the end of a project, the collective wisdom is discussed and documented, it becomes knowledge that survives the breakup of the team. People then are able to carry with them lessons learned by the team as well as those learned on their own.

Possible Goal # 5: Repair damage to the team. Creating and delivering a major piece of software is tough work. During the process, people are panicked and stressed, and they behave in uncharacteristic ways. Team members will be exhausted after putting out extreme amounts of energy and after making unreasonable personal sacrifices. Sometimes, things are said (or not said) in the heat of the moment. In each of these cases, relationships of all types will need mending.

All of this adds up to a problem that needs to be addressed. If team relationships have been damaged, a retrospective provides an excellent opportunity for colleagues to acknowledge hurt feelings and to evaluate the damage done in order to determine what must be repaired. A retrospective can provide a time to honor the heroic yet often unrecognized efforts of individuals. It should be seen as an opportunity to establish contacts that will help preserve relationships in the future. It is a time to engender honest enthusiasm for starting the next project.

Often, organizations reject this goal of repairing damage to the team because they take what I consider to be the archaic view that it is not proper to deal with feelings in the workplace. In my experience, high-performance teams are fully capable of developing safe ways to discuss the feelings and needs of each member.

Possible Goal # 6: Enjoy the accomplishment. As a rule, software developers are goal-oriented problem-solvers. They rarely stop to notice what they have accomplished. A retrospective provides an opportunity for such people to stop and reflect on how far they have come, rather than focus only on the current problem or the next one to be solved. Without such reflection, “post-project blues” can set in. If they have not taken time to savor the victory, people risk entering a new project without having recovered from the difficulties of the one just completed. The developer who suffers from “lost hope” feels that nothing will be better next time, and that the next project will be just as difficult and crazy.

Second Consideration: How healthy is this organization?

Another area to consider when designing a retrospective is how evolved the organizational culture is in the area of human interaction—that is, how do members of the team deal with difficult issues? Some cultures have developed highly functional ways of communicating with each other, working together, and solving problems, while others demonstrate dys-functional behavior when faced with problems.

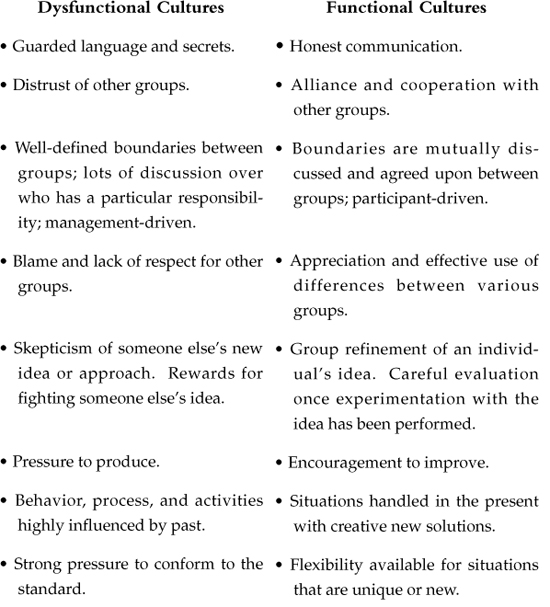

The table that follows shows a list of characteristics to look for when you identify a culture as either functional or dysfunctional.

Your own observation regarding the degree of involvement of a culture is very important. The less functional an organization, the more effort you will need to put into ensuring that the retrospective stays focused in a healthy direction—on learning rather than on fault-finding.

It’s important to note that no organization is likely to be totally functional or totally dysfunctional. There is a continuum along which most organizations lie, falling somewhere between the two extremes. The table can be used as a starting point for an understanding of the approximate state of the culture, and perhaps to begin a dialogue with the client about areas for improvement.

The greater the dysfunction, the fewer retrospective design choices you have. With highly dysfunctional organizations, either you need to be skilled at dealing with personal interactions and antagonism or you need to lower the goals of the retrospective to avoid serious conflict.

I do not recommend avoiding difficult issues, since limiting the scope of a retrospective brings little benefit to the client. Instead, I focus portions of the retrospective on ways to improve the health of the organization.

Third Consideration: Do I have the skills to lead this retrospective?

Whatever the health of an organization, two other factors that must be considered in the design of a retrospective are, first, your own skills as a facilitator and, second, your level of understanding about the work done during the project. The fact is, a given facilitator may not be sufficiently qualified and/or ready to lead certain retrospectives. Below are some criteria to use when evaluating your own or another’s ability to lead a particular retrospective.

A facilitator must be an outsider. A facilitator needs to be an outsider rather than a member of the project team. Facilitators need to remain neutral during the retrospective—watching the process, building a safe environment, helping people participate, summarizing points as the story lines begin to weave, and encouraging the exploration of alternatives.

A facilitator must be technically competent. A good retrospective facilitator needs to have software development experience in order to understand the nature of the work done during the project. The more a facilitator knows about what is to be reviewed, the better he or she will be at leading discussions and helping the team move toward a collective understanding. As facilitator, you should understand the project’s process, architecture, tools, components, companion groups, suppliers, vocabulary, and so on.

A facilitator must be a Betazoid. Because a retrospective involves leading people through a number of exercises (some designed to cause individuals to think, others designed to encourage group discussion), a facilitator must be able to manage both people who talk too much and people who don’t talk enough. The facilitator must establish and maintain an environment in which it is safe to speak out about unpleasant, embarrassing, or emotional issues. The facilitator needs to be skilled at resolving conflict, mediating, and helping transform blame into constructive information. He or she must be able to sense the emotion of the team as the retrospective proceeds. In short, a facilitator needs the skills of Deanna Troy, the telepathic Betazoid counselor from Star Trek: The Next Generation. Luckily, these skills can be learned—see Chapter 9 for details and refer to my Website: http://www.retrospectives.com.

All that having been said, you can lead a retrospective even if you don’t presently have all the required knowledge and skills. It is possible to form a facilitation team by employing one person who is skilled in software development and a second person who is skilled in managing personal interactions.

A True Story

After I had led a very successful retrospective, one of the participating managers invited me to work with his team on its next project. During this effort, I introduced analysis modeling techniques, object-oriented design, quality assurance techniques, project-management improvement methods, and several other skills to change the culture of the group.

In the middle of the project, the manager left the team and I was asked to serve as acting manager. Eventually, a replacement was hired—a manager who focused more on budget than on process improvement—and I resumed my role as a member of the team.

When the project ended, I scheduled a retrospective, but explained to the new manager that I could not facilitate since I was part of the team. I recommended a colleague to run the retrospective, but the manager responded that he could not justify the cost of paying me to attend the retrospective as a contributor while also paying someone else to serve as facilitator. Because he’d heard I was an experienced facilitator, he believed I could play both roles.

While my ego tempted me to give it a try, my wisdom won out. I’d witnessed too many failures by people who had attempted to both facilitate and participate in a retrospective. In such a dual role, my focus would have been divided. When I spoke, there would be confusion as to whether I was speaking as facilitator or as participant. To do both would be unfair to the group and to me. Since it didn’t seem as though the manager would change his mind, I had two choices: Cancel the retrospective, or hire the facilitator I had recommended we use and then pay for her services myself.

The first option seemed completely wrong. We had created a team that viewed holding a retrospective as essential to any professional software group’s growth. Canceling the retrospective would have been equivalent to saying, “Our team doesn’t need to continue to grow.” An additional reason for my commitment to holding the retrospective was that, during the project, I had encouraged team members to contribute suggestions on process improvement, but because of scheduling difficulties, I had asked them to save some of their new ideas for the retrospective. I felt my credibility was on the line.

The second option seemed extreme. The idea that I should have to pay for my client to learn about process improvement struck me as intolerable, but the truth was, such a great team deserved a good retrospective experience (and a better manager!)—and so I selected the second option. I paid for the facilitator, justifying the expense as a gift to team members with whom I had truly enjoyed working. At the same time, I decided that I needed to find a new client.

Armed with knowledge about the three areas of consideration (goals, organizational health, and your own skills as facilitator), you now can finalize details about your retrospective design. The questions in the following sections should help you plan.

Who Should Attend the Retrospective?

In my early retrospectives, I included software developers only. In particular, managers were excluded. My rationale was that software developers would be more likely to discuss problems about management if their managers were not in the room.

My main goal in these early retrospectives was to develop a report for managers that recommended various changes. We would work very hard on the report, then deliver it to management, hold briefings, and try in various ways to communicate to the managers what we had learned about the project. The long-term results were usually disappointing, and very little would change within the organization. I now believe that one reason the results of those early retrospectives were poor was because the managers had not participated in the retrospective, so they were not privy to the discussions that led to the recommendations, and therefore did little to see that the recommendations become practice.

Managers do need to be involved in retrospectives. Furthermore, since we are looking at the whole project, we need to include key people from external organizations involved in the development effort. Over time, my retrospectives have shifted from small, intimate gatherings to larger, somewhat-more-inclusive sessions.

Based on my experience, I have developed a list of retrospective candidates, categories of personnel who may know something informative about the project. Not everyone on the list gets invited, but as I work through the categories of candidates, my clients often think of additional people. The list includes people from the following areas:

• sales

• technical support

• customer support

• customer training

• quality assurance

• procurement

• manufacturing

• key customers

• hardware and software developers

• technical writers

• third-party vendors

• contractors

One important but often overlooked person to include is someone who may have a truly unique view of the project: the department secretary.

I try to involve as many viewpoints as possible in a retrospective while keeping the group small enough to be managed. Usually, my clients can identify individuals with an important piece of the story to tell as we work through the list together.

How many people participate in a retrospective affects how it should be designed, its length and cost, as well as what level of demands are made on the facilitator. The largest group for which I have served as sole facilitator consisted of nearly thirty people. That particular team scored quite high on the functional chart, and the project was perceived as a success. For larger groups, or ones in which the culture is less evolved or the project has elements of failure, I generally build a team of facilitators. The largest team of facilitators I’ve worked with consisted of four people. We led a cross-departmental retrospective of a failed project, with a total of 68 participants.

Where Should the Retrospective Be Held?

A retrospective can be held on site, off-site local, or off-site residential. An on-site location has the advantage of being less expensive for the company than a residential session. Other advantages include the probability that the site is familiar to and easily accessed by the participants, that other project members who are not part of the retrospective can be consulted when needed, and that project artifacts not gathered before the start of the retrospective are readily available. But an on-site meeting has disadvantages: It may be seen by participants as cheap and therefore not important, the site is “the same old place,” the retrospective is easily interrupted, and participants may not prepare as well since they can duck out to look for whatever materials they need at the last minute.

In cases in which the project’s budget has been depleted or holding an off-site meeting is against the organization’s policy, I have facilitated on-site retrospectives, but I usually have found that the team achieved far less than it would have accomplished if the retrospective had been held off-site. Even when a retrospective is held at a premium on-site location (such as the executive dining room or the corporate board-room) and a “do not disturb” policy is established, the participants seem to offer the “same old thinking” and the “same old behavior” that crippled the project itself. Limitations seem easier to accept and new ideas easier to kill when a retrospective is held on-site. In short, the on-site retrospective isn’t seen as having any long-term significance. Because of this, I no longer facilitate on-site retrospectives.

When deciding between recommending an off-site local or an off-site residential retrospective, I consider the needs of the group in the context of the available budget. A residential retrospective is the most costly, of course, but it provides the best opportunity for participants to learn how to change the way future work will be performed. Around-the-clock immersion yields amazing understanding, learning, and growth. For most participants, a residential off-site meeting will be seen as a form of reward or benefit. The feeling of gratitude this evokes makes the retrospective an important part of the project, and residential retrospective participants tend to work harder and learn more than participants in other types of retrospectives.

A local, off-site location from which participants return home at night has the advantage of being considerably less expensive than a residential, but the depth of learning is less and the potential for real improvement is smaller.

The decision to hold a residential meeting is usually made by someone very high up in management or by an upper-level manager rather than by the project manager. Neither of these higher-level managers is likely to be close to the project and may not understand the potential value of a residential retrospective. Typically, the high-level manager must veto all sorts of proposals and may automatically reject the residential retrospective option without giving it much thought, perhaps because it sounds like a boondoggle or because the money simply isn’t available for a residential meeting.

If the money really is not there, then an off-site, local retrospective becomes a reasonable choice, but I do not settle for one until I have urged the decision-maker to calculate the cost of a residential retrospective compared with a non-residential one, including participants’ salaries and the cost of lost days of work, to see exactly how much money is involved. The incremental cost of a residential meeting over the cost of a non-residential is often quite small.

In a case in which the decision-maker is worried that the off-site facility is some sort of a boondoggle, I describe what I usually see at a residential retrospective—people working very hard, often well into the night. With the project manager, I discuss ways to reassure the decision-maker about the value of the retrospective, and look for goals common to both the project manager and the decision-maker. For example, I might propose we lower costs by choosing a truly no-frills location, such as a scout camp during the off-season, or that we lower the boondoggle component by choosing a site with no discernible fun quotient (certainly not a site near a golf course!). Actually, this no-frills, sensible location is the type of site I prefer, for reasons discussed more fully in the next section.

Selecting a Residential Site

For any retrospective, I need a room large enough to hold the entire team, plus several break-out spaces for smaller groups—ideally one area per four or five people. With schedule slips likely, reserving a residential location before the end of a project is difficult. As a result, residentials usually end up at rustic places that are not in high demand, and that require a bit of travel. These limitations actually turn out to be benefits.

If the space selected for the residential retrospective is too rustic, that is, if it is run-down or bare-bones, the participants usually work together to make it more comfortable. If it takes at least two hours to drive to the site and there is limited parking, all the better—I want team members to carpool. Driving together enables people to talk, to re-establish relationships, and to discuss the past project, the next project, and the retrospective. And, since people coming and going disturbs the process, holding the meeting some distance away limits the temptation for people to return to work to attend to “important” business or to their homes for personal reasons.

When Should the Retrospective Be Held?

The best time to hold the retrospective is from one to three weeks after the end of the project. It makes no sense to have a retrospective before the project is completed, and even less to hold it after the next project has begun. Scheduling is tricky, since the schedule needs to be projected before the project ends, resulting in a great deal of guessing about the actual dates.

As a seasoned facilitator, I know dates slip. My business is service-oriented, and so I work hard to keep my schedule open enough to accommodate these slips. I also keep close tabs on a project as it nears its end so that I can use my finely honed sense of intuition to estimate when the project is likely to finish.

I never hold a retrospective immediately after the end of a project; at that point, no one has the necessary energy. Team members need a break—some time to sleep, to re-connect with family and friends, to take care of postponed personal business, and to do a bit of reorganizing at work.

How Long Should a Retrospective Be?

Simply stated, effective retrospectives require about three days.

I once received e-mail from a person whose manager had allocated one hour for a retrospective of a six-month project. The writer of the e-mail had been assigned the responsibility for making sure the retrospective would be a success, and she was looking for advice. My response to her was that so brief a retrospective could not be successful.

While I have heard of retrospectives being held in an hour, or in half a day, the following comments sum up those brief attempts:

We tried retrospectives. After a while, we discovered that each review was making the same recommendations. Clearly, nothing was changing, so we decided that retrospectives are a waste of time. We don’t do them anymore.

It is sad to know that such an effective learning tool as a retrospective was ruined in part because not enough time was allocated to do one properly. I find it ironic that “waste of time” was cited as the group’s reason to avoid retrospectives, when the problem was that the group had not allowed enough time in the first place!

It is unreasonable to believe that significant learning about a multi-person project that lasted several months can occur in an hour. At best, such a brief retrospective may serve to identify a few symptoms of real problems, but participants are unlikely to be able to do more than recommend poorly analyzed, partial solutions that do not fully address the issues.

There are two probable arguments the decision-maker will make for keeping the retrospective brief: First, he or she may cite insufficient funds to pay for the longer retrospective. Second, he or she may believe that a longer retrospective cannot produce results commensurate with the time it will take. The project manager may also argue against holding a full retrospective because of a secret wish to avoid the detailed scrutiny involved with a longer review of the project while still appearing to favor holding one.

The first reason, lack of money, can be repudiated with some numbers. For example, during a six-month project, just one member of a team is likely to work a minimum of 120 days on up to 150 days (or more if that person works weekends in addition to evenings). A three-day review takes less than 3 percent of the project time—a very small portion of the budget—and a well-run retrospective can be expected to cut six days or more off the next project, yielding a 100 percent return on investment.

We can counter the second argument by providing information about what happens at a retrospective, sharing stories about successful retrospectives, and by describing the results retrospectives bring to an organization.

If the resistance derives from a person’s wish to avoid a serious review, the facilitator would do better to refuse to hold the retrospective at all than to risk using it inappropriately or where it is not wanted. However, before I refuse to participate, I try to change the decision-maker’s or project manager’s attitude. Generally, I begin by questioning the person to try to understand the nature of his or her reluctance. Once I have an individual’s fears in perspective, I see whether I can be reassuring that my approach will facilitate a safe retrospective. Often, a person’s fear is based on a single bad experience, so I try to learn what happened in the past, and then explain what will be different this time.

A True Story

I was contacted by Eric, an administrative assistant to a high-level manager whom we’ll call Ron. Ron wanted Eric to schedule a retrospective to be held in about six weeks. After our initial discussion, I told Eric I thought a retrospective would be a good idea, and asked him to set up a meeting with Ron so we could discuss the details of the retrospective.

For five weeks, Eric and I scheduled and re-scheduled meetings, but Ron always needed to be somewhere else at the last minute. He was at emergency meetings related to getting the software project finished, away on an emergency trip visiting customers, on an emergency vacation with his family, and so on.

Finally, with the retrospective scheduled to begin in just one week, I still had not had a chance to discuss goals and choices with Ron, and so I suggested to Eric that we postpone the retrospective indefinitely until everyone had had a chance to slow down, think, and plan.

Eric told Ron my recommendation. Ron’s response as he ran out the door was predictable: “Definitely not! We need to learn how to prevent all these emergencies. Tell Norm that I don’t have time to meet with him. Maybe he should just plan on winging it, and we can talk during the retrospective.”

When Eric reported this conversation to me, I knew why Ron had so many emergencies: He didn’t take time to plan. It would not have surprised me if this became Ron’s major realization as a result of the retrospective. Yet I knew we wouldn’t get to that point—I couldn’t proceed with the retrospective because I knew that to do so would only invite more emergencies.

I gave Eric the following brief message to convey to Ron: “I can’t lead a retrospective until you have time to sit down and plan it with me. As a result, I’m canceling my plans to lead the retrospective next week. Please call me when you have the time to plan.”

Ron never called. He was too busy, right up to the day he was fired.