Chapter Nine. On Becoming a Skilled Retrospective Facilitator

Bee and Ant long ago had resolved the problem of Ant’s dissatisfaction with the beehive condominium, but Ant’s difficulties had not ended there. He still had no place to live.

Desperate to relocate, Ant set off in search of a new home, and within days, he found a baby grand piano in a lodge built at the edge of Owl’s woods. Without a moment’s hesitation, Ant moved in. Living in the piano was like living at a picnic! There was a continuous supply of crumbs dropped by humans having parties, and Ant was a happy camper—except for one thing: He wanted to play the piano but couldn’t read a single note!

In hopes of remedying this shortcoming, Ant visited Owl. He knew Owl was not musically inclined, but he thought the wise old bird might be able to recommend a great book. After all, Owl read everything he could get his wings on. Surely, he would help.

Finding Owl asleep in his usual tree, Ant whispered, “Owl, how can I learn to play the piano?“

Owl stirred sleepily, “I don’t know. The piano is something I’ve never tried.”

Ant persisted. “Owl, you’ve learned so much from books. Maybe you can help me find a book that will teach me to play the piano?”

Owl stretched before he responded. “Ant, you can learn great ideas from books, but to put those ideas into practice, you need more than just a book. You need a teacher—and you need to work repeatedly at what you are taught. If you are really interested in playing the piano, why not ask Hummingbird or Nightingale to teach you—music is their life.”

Reading a book will only get you part of the way toward your goal, which should be to become the best retrospective facilitator possible. You will also need to work with teachers—to help fine-tune your facilitation techniques, to practice them in safe environments, and to partner with experienced facilitators until you become completely comfortable and proficient in the retrospective setting.

I was not born a skilled facilitator. I was fortunate to be apprenticed—albeit unofficially—by an experienced facilitator named Don Reifer. During my first retrospective, Don and I spent the evenings discussing the days’ events. Don explained why he reacted the way he did during each of the sessions.

I practiced my general facilitation skills as a leader of numerous requirements-gathering projects. To learn interpersonal skills, I studied the deeper issues of how people interact. I did this by attending courses geared toward exploring people-related issues as well as courses designed for marriage and family counselors. I also learned interpersonal skills by doing volunteer work for churches and community centers, focusing on environments in which emotions ran high. I assisted counselors leading groups of people in divorce recovery, people coping with the loss of a loved one, and people experiencing the uncertainty and grief of living with a terminally ill spouse.

Through this volunteer work, I came to appreciate that positive learning occurs when people are able to express their emotions. I used this realization to improve my skills as a facilitator. During retrospectives, when emotions surfaced, I learned to not shy away from exploring the story behind those emotions. At the same time, I learned to respect a person’s right to keep his or her thoughts private. I never force participants to explore a topic if they don’t want to. Remember, for a retrospective to feel safe, everything must be optional, including the discussion of feelings.

Six Lessons

My earliest retrospectives involved successful projects with teams whose members had worked well together. Over time, as I became more experienced, I led retrospectives of unsuccessful projects, dealing with increasingly serious problems. I partnered with experienced facilitators every chance I could. Through their instruction and through the school of hard knocks, I have learned valuable lessons, which I share below.

Lesson 1: Manage current topic, flow of ideas, and quality.

Acquiring basic facilitation skills is a must for anyone intent on leading retrospectives, but advice on exactly how to go about acquiring the skills is beyond the scope of this book. My Web-site (www.retrospectives.com) suggests courses that can be taken by fledgling facilitators, but newcomers to the skill set may find it useful to keep three fundamental rules in mind.

1. Make sure that everyone knows what is being talked about, and that all are talking about the same thing.

2. Channel the flow of ideas to keep people focused and to keep abreast of people’s moods.

3. Maintain a high standard for the quality of discussion.

Rule 1: Make sure that everyone knows what is being talked about, and that all are talking about the same thing. A retrospective involves different minds processing a vast amount of new information and attempting to reconcile that information with past experiences. It is natural for people to become distracted and lose track of what the group is trying to accomplish, or for the team to forget the goal of an exercise.

One of your jobs is to accept that people will go off on tangents, and then bring them back to the current goals and objectives of the exercise. As tangential topics surface, you will need to be patient and not take offense. The conversation does not mean that they are not listening to you, but rather that you are causing them to think about something new and to learn. I maintain my patience first by consciously relaxing, and then by reminding myself that the digression is really a compliment. It’s an indication that I’m doing my job!

Rule 2: Channel the flow of ideas to keep people focused and to keep abreast of people’s moods. Put twenty or so people in a room with no guidelines to structure their interaction, and you have a party. Ideas flow everywhere. Naturally gifted speakers will talk easily and frequently and may try to engage their colleagues in discussion; others, who might be gifted thinkers, may spend their time reflecting on what they are hearing. One beauty of being human is that we are all different. However, without structure or a format, some people may talk too much (and sometimes say very little!) while others won’t be able to get a word in.

It is the facilitator’s job to ensure that everyone has an equal opportunity to speak, while moving each discussion toward a resolution. “Equal opportunity” does not mean that everyone must speak, but that when someone wants to, he or she can. I try to create an environment in which conversation is natural and free-flowing. If too many people want to talk, I generally announce, “I’m going to play traffic cop now,” adding that I will only respond to raised hands. As traffic cop, I stand near the center of the room and silently point to people who have their hands up to let them know that I’ve seen them and that they are second, third, and so on, in line to speak.

Another objective of channeling the flow of ideas involves helping the community reach closure and move on. If I hear a conversation that goes around in circles or delves into vast amounts of history with no resolution in sight, I stop the discussion and ask people to formulate a conclusion. I might ask, “What conclusion or lesson can I record here?” or, if no conclusion is forthcoming, I might suggest a conclusion and ask, “Is that close?” Soon, participants in the retrospective or postmortem realize that every discussion needs to end in some sort of learning to be captured on a flip chart, and they begin to steer themselves toward that goal.

Channeling the flow of ideas also helps me to read the mood of the participants to see whether anyone needs a break, or to assess whether people’s energy is waning on the particular exercise, indicating that we should shift to another one. Throughout the sessions, I observe body language to monitor people’s physical and mental states, but I always test my instincts and observations before I act upon them. I might say, “It looks to me as if some of you need a break. Am I right?” If no one supports my observation, I ask people to fill me in on what else is going on. Usually, this little bit of intervention clears the way to closure.

Rule 3: Maintain a high standard for the quality of discussion. This task involves listening to what is said and making sure all discussions confirm that group members show each other complete respect during discussions, that they espouse as truth the statement that “we did the best we could, given what we knew at the time,” and that everyone remembers that the goal is to learn how to improve.

As I listen, I am on guard especially for any jokes or cutting remarks made at the expense of someone else on the team or in the room. If I hear any, I stop the discussion, remind the group of our fundamental ground rules, and encourage an apology if necessary.

In addition, I listen for ineffective communication—coded or garbled messages, partial messages, or messages tainted with blame, guilt, or the like. In such cases, I help the speaker rethink and rephrase his or her ideas so that any appropriate message is conveyed without hindrance.

Lesson 2: Ask for help when you need it.

On occasion, I accept a retrospective for which my skills turn out to be inadequate. I learned early to be able to admit that I was in trouble and to ask for help. Every time I’ve asked for assistance, I’ve found someone—a colleague, a consultant, or even a participant in the retrospective itself—who could help me turn the situation around.

Although it is key to be able to ask for help, one must also be careful to maintain a network of contacts who are available to serve as emergency lifelines. Just knowing you have someone you can call for advice reduces anxiety and increases your effectiveness.

Lesson 3: Avoid triangulation.

There are times when someone in a retrospective relates something to me off-the-record about a third party. He or she may want to explain what this colleague thinks or why the person reacts in a particular way, or he or she may be trying to make me a confidante to take sides in some external exchange.

I’ve learned to listen to the information, but not necessarily to accept it at face value, or act on it. I try to redirect this conversation as it should occur between the speaker and the third party. I ask whether the speaker has discussed the topic with the other person. If the answer is no, I explore how a dialogue might be initiated. If the answer is yes, I question what the speaker hopes to accomplish by confiding in me. Usually, my demeanor and guidance enable the speaker to take proper action to rectify the situation.

I work hard to maintain my role as a neutral third party. By reminding myself and others that my job is to facilitate discussion and learning, not to pass judgment or attempt to “fix” anything or anyone in the community, I keep the retrospective on track.

A True Story

During a break in a retrospective, Fred, the manager, thought his senior technical lead, Mike, was contributing “too much, as he always does.” It was early in the retrospective and I didn’t think Mike’s participation was out of line. Instead, I found Fred’s comment curious. I asked more about it and found that Fred felt Mike was holding back the growth of the junior developers by always having an answer. When I asked Fred if he had mentioned his concern to Mike, he said, “No, I fear Mike might be insulted” and he admitted that he didn’t know how to proceed.

I arranged to have lunch with both Mike and Fred. When the discussion turned to team maturity, I asked, “Mike, if there were things you could do to improve team members’ growth, how would you like to hear about them?”

A bit exasperated, Mike replied, “Norm, just tell me.” “Suppose team members had a similar message, how would you like to hear it?”

More exasperated, Mike said, “Then they should just tell me.” “Would that also hold for Fred?”

I turned to Fred and said, “I think we both would like to hear what you have to say.”

The rest of the lunch conversation was magical. Mike learned that Fred thought he was trying too hard and was condescending when the junior developers contributed an idea. Fred learned that early in the project when everyone decided Mike “was dominating and touchy,” Mike was actually caring for his dying parent—and was therefore reasonably out-of-sorts. Now time had passed and Mike was frustrated because he felt he was in a “dome of silence.” No one else contributed when he was around—he had to do it all himself.

Mike and Fred finished lunch with a new respect for each other. Simultaneously, they commented, “We need to talk honestly more often.”

Lesson 4: See things from a systems perspective.

When I encounter a situation that seems to make no sense, I search for the bigger picture. For example, members of a community may look at an event or a decision and misinterpret the intent, resulting in deadlocked discussion and review. Most frequently, this occurs when people are looking at the matter solely from their own point of view—a distortion that can be remedied by directing them to see where the problem fits within a whole-system perspective.

At other times, an individual may appear to be the source of the deadlock. I once facilitated a retrospective in which one woman was accused of not being a team player, of trying to impose academic theory in the real world, and of being obsessed with process. She was labeled as a complainer because she wanted better specifications, better and increased interaction with the customers, a way to ensure needed change and version control, and testing procedures that would not be sacrificed in order to deliver the system earlier.

She was viewed as the problem by the whole community—but, in reality, she was the only one willing to stand up and say, “Our approach to building software needs work,” and she was right!

By freeing the group to look beyond a single perspective to the whole system, the facilitator can move the community to a new level of learning and understanding.

Lesson 5: Seek first to understand, and then to be understood.

In The Seven Habits of Highly Effective People, Stephen Covey advocates that we learn to really listen to what a person is trying to say. It is easy for me to assume that I know what the speaker intends and then to try to manage the group’s discussion based on my own experience and assumptions, only to discover later an interesting twist that I hadn’t anticipated!

Over the years, I have learned first to listen and then to ask questions in order to understand the speaker’s perspective. Sometimes, my initial conclusions are correct, and I could have jumped ahead and explained the issue to the group. However, careful articulation of the problem is important if group members themselves are going to be able to understand the issues well enough to arrive at a solution. Offering a solution while most of the community is still trying to understand the problem does not work.

The most effective approach to problem solving is to enable members of the retrospective community to discover their own answers. Sometimes, they arrive at the solution I expect. Sometimes, they find a better one. By asking more questions and giving fewer answers, the facilitator helps the team to assure future success.

Lesson 6: When something isn’t working, try something different.

Jerry Weinberg’s The Secrets of Consulting introduced me to what seems now to be an obvious but brilliant idea: If you are in the middle of holding an exercise or participating in a discussion and progress is not being made, then try something different! It doesn’t matter so much what you try, since what you are currently doing isn’t working, but that you make a change.

How do I determine what to try? In such situations, I’ll think through past experiences to see whether there is anything that might work. If not, I’ll trust my intuition. Usually, my gut feelings will lead me to the invention of a new exercise. Trusting your creativity is important. Sometimes, I’ll start a new exercise without knowing exactly where it will lead, but I always let people know we are trying something new. If it doesn’t work, we move to another exercise or approach.

Sometimes, people react negatively to my suggestion of inventing something new, perhaps because it scares them to have no plan and little idea of where they are going. Veteran facilitators especially seem wary of trying something radically new, believing it is the facilitator’s responsibility to be in control of the retrospective. My response is that this belief is valid, but that successful facilitation depends on one’s view of “control.” Trying something new to help a community move past a barrier seems to me to be an example both of good facilitating and of good leading.

I suspect that many a facilitator’s fear of trying the unknown comes from a lack of experience as well as a lack of confidence. (If one tries new things, one will fail sometimes and succeed at other times. By trying, you discover you can recover.) Long ago, I studied improvisational comedy with a group called ComedySportz. The lessons helped me become comfortable with leading “in the moment,” trying something—anything—even if I don’t believe I’m good at it or don’t know what I’m doing. Through improvisation, I learned to try new approaches while listening and reacting to my audience’s response. Another way to build confidence that you can venture into the unknown, survive, and even succeed beyond your expectations is through organizations that promote public speaking. The Toastmasters organization has an exercise called “table topics,” in which people speak extemporaneously on a topic. These techniques won’t guarantee you’ll pick the best “something different” to try when what you’ve been doing is not working, but they will lend a boldness and confidence to your manner—an attitude that can prove catching!

Understanding the Facilitator’s Procedures

As programmers, we use the word procedure all the time, but I don’t think we appreciate the power of the word beyond the context of programming. One dictionary tells us that a procedure is a series of steps taken to accomplish an end.

Think how a surgeon uses this word. During an operation, a surgeon might select a procedure from his vast mental collection to solve a particular situation he or she discovers—usually in real-time.

As a retrospective facilitator, I’ve collected a number of retrospective procedures, stored in my mind and ready for use when an applicable situation arises. These procedures are not retrospective exercises any more than a single medical procedure is an operation. Nevertheless, I may use one or more of these procedures to help a particular exercise run more effectively. Similarly, I may use a single procedure in more than one exercise during the same retrospective, if that is what the situation calls for.

In the remainder of this chapter, I list commonly used procedures that I use while leading a retrospective.

The “Dealing with Conflict” Procedure

There are times when a retrospective gets bogged down by a conflict. As with most battles, we expect that one side in the conflict will win and the other will lose, but as long as those involved see winning and losing as the only possible outcomes, the conflict will remain unresolved. Whenever preexisting or new conflict situations arise, I employ a tailored conflict-resolving approach.

Basic Concept

Facilitating resolution of a preexisting conflict involves several steps that you can take:

Step 1: State that conflict, as such, is neither bad nor good, but is simply a fact of life. Within conflict, opportunities for discovery or invention exist that can lead to a better solution than either party might have initially imagined. When this optimism is expressed to groups in conflict, it usually arouses their curiosity and helps them begin to move away from the source of conflict itself.

Step 2: Ask both parties whether they want to work on resolving the conflict. Explain that the process involves looking at the events leading up to the conflict and at alternative resolutions, and tell them they’ll need to abandon their current position for a time. Let them know, however, that they are free to return to their current position at the end of the process. Try to sense whether the participants are serious about searching for a solution. If they are not, then stop your intervention—you can’t help them if not everyone wants to solve the conflict. In most cases, they will be serious and will want to move forward.

Step 3: Explore the two parties’ different positions by asking them to articulate their goals, fears, concerns, intentions, and desires. It’s quite possible that each party arrived at its position without fully understanding how it got there. Because the goal of this discussion is understanding, not the passing of judgment, all parties need to hear their own and their opponent’s reasons—and then honor these beliefs as valid for the owning party. When all issues are understood (but not necessarily accepted) by all parties, move to the next step.

Step 4: Review each party’s statements and interests and identify issues that are common to more than one party. Finding interests or goals that opposing parties share might take some creativity (for example, try restating the matter from a different slant) but it can be done, and it is a way to build common understanding among parties. This is often enough to resolve a conflict; in the best of cases, a proposed solution might be offered and accepted rather quickly. If it is not, proceed with identifying issues that are not common, being careful to establish how important each of them is to the owning party. Then, move to the next step.

Step 5: Involve all participants in finding new solutions. These must be solutions that have not been proposed before, which take into account everyone’s motivations and concerns. If you have rated the issues according to importance, you might first explore solutions that address all the important factors before you see whether the parties are willing to drop less important issues. If high-quality solutions are not identified, give participants some time to think quietly by themselves. Do this by stopping the session and resuming at a later time.

Step 6: List all possible solutions that at least partially resolve the conflict and have the community evaluate and select the most satisfactory candidate. Then, ask each party whether it wants to return to its previous position. Participants are usually ready to proceed with the new jointly developed solution.

Applied to Retrospectives

When a conflict arises during a retrospective, you have two choices: Either you can help resolve the conflict immediately, or you can observe that the conflict is beyond the scope of the retrospective. In the second case, you’ll want to refer the conflict as a topic for special handling, and move on to other issues. If you choose the second approach, add the issue of resolving the conflict to the community’s “to do” list. All action to help resolve the conflict, whether overseen by you or another party, should be conducted after completion of the current retrospective.

Factors to consider include the following:

References for Further Reading

Fisher, Roger, and William Ury. Getting to Yes. New York: Penguin Books, 1981.

This book introduces the process behind the six steps discussed above in the Basic Concept section. An easy-to-read book, it gives a great deal of practical advice on how to work through polarized positions.

Crum, Thomas F. The Magic of Conflict. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1987.

Crum discusses dealing with conflict from a philosophical point of view, and provides a discussion of how people can live their ordinary lives and still be at peace within the world.

Hocker, Joyce L., and William W. Wilmot. Interpersonal Conflict, 3rd ed. Madison, Wisc.: Wm. C. Brown Publishers, 1991.

Hocker and Wilmot present a comprehensive treatment of the subject of conflict. Used in university courses on mediation, the book surveys various theories on how to handle conflict, covering the material in greater depth than can be taught during a retrospective, but at a level that is valuable for a facilitator to have mastered.

The “Handling Resistance to Change” Procedure

Someone once asked me how I deal with resistance to change in an organization. My reply was, “I don’t find resistance to change to be a problem.” It wasn’t until much later that it dawned on me that I handle resistance to change by not seeing it as a problem.

Instead, I see resistance as a carrier providing information about a person’s thinking process and I use it as an opener for more dialogue. Whoever coined the phrase, “You can’t teach an old dog new tricks” didn’t know how people learn! Although it is true that children generally embrace new ideas and activities, adults show varying degrees of acceptance or of reluctance. Resistance to new ideas is very natural. The behavior shows that an individual is actively engaged in evaluating the new possibilities against his or her past experiences. This mapping of new ideas onto past experiences is a fundamental part of adult learning. I, for example, have conditioned myself to respond to resistance as if it is an invitation to participate in this mapping.

When someone resists a change, it is usually for one of two reasons:

• The individual is trying to avoid some pain that he or she thinks will come if the new way of working is adopted.

• The person is trying to prevent something that is positive and enjoyable in the current situation from being lost by the new way of working.

If you realize that resistance to change is due to an interest in either avoiding pain or maintaining joy, you can ask specific questions in order to better understand the motivation behind the resistance—and thereby help people to move beyond it. There is a two-step approach that can be taken: It involves discovery first and then a coaching-and-learning effort.

Basic Concept

Step 1: Determine what the resisting individual is avoiding or protecting. The key attributes a facilitator needs to express in this step are patience, careful listening, and taking a position not associated with a specific outcome.

Step 2: Work with the resisting individual to discover ways to help him or her avoid the pain or maintain the joy in the new way of working. In some cases, this means learning more about a topic so the participant feeling the conflict realizes that whatever he or she wants to avoid or maintain is satisfactorily addressed in the new way of working. In other cases, it means modifying the intended changes to make them compatible with those required by the resisting individual.

Both the discovery-oriented first step and the coaching-and-learning second step may require more than one discussion session. Many people learn by alternating cycles in which they think quietly on their own with those in which they discuss matters openly with a group of peers. In the discussion part of the cycle, people often will talk about all aspects of the intended change, including any negative feelings they have. The comment, “This change is inappropriate because . . .” is not a threat to the intended change, but rather part of the learning process.

Applied to Retrospectives

Discussing the future usually leads to proposing change. As the discussion occurs, I listen for comments that might give me clues about the pain that people fear or the joy they value. I help them articulate their concerns, and challenge the teams proposing change to address those concerns. I create time-outs in the various exercises and ask people first to think quietly, and then to write about the proposed changes on a card or in a journal. I follow this activity with discussion, breaking the community into small groups, working with the whole community, or sometimes meeting only with individuals as part of my follow-up after the retrospective.

The “Four Freedoms” Procedure

Every now and then, as you prepare for a retrospective, you may encounter workers who believe themselves to be disem-powered. One reason for the feeling may be that the workers don’t know how to take charge of matters themselves and believe that their organization has deliberately disempowered them. They may be misinterpreting the motivation behind such legitimate management endeavors as information-seeking or project-control activities. Another possibility is that managers actually have unintentionally disempowered workers. In rare cases, management may intentionally seek to disem-power workers, but I don’t know much about these environments, since the organizations that foster them don’t hold retrospectives!

Most managers learn to manage on the job with little or no training, and may have incorporated practices that make sense from their point of view but not from the workers’ perspective. Or, they may simply be unaware of the implications of the specific practices to their workers. With either of these two situations, the “Four Freedoms” can help.

Basic Concept

The “Four Freedoms” are universally found in all empowered workplaces:

1. You have the freedom to talk about the project the way you see it, rather than the way others want you to see it.

2. You have the freedom to ask about any puzzles.

3. You have the freedom to talk about whatever is coming up for you.

4. You have the freedom to say that you don’t really feel you have one or more of the preceding three freedoms.

These four freedoms are deceptively simple but effective. That you have the freedom to talk about the project the way you see it gives permission to you along with everyone else to speak about the project. Sometimes, people are afraid to say what’s really going on for fear that they will be labeled disloyal, complainers, or whistle-blowers. This freedom gives everyone the opportunity—and the responsibility—to say, “We are off schedule and will not easily get back on.” It is this kind of input that managers need to hear in order to effectively manage their projects.

The freedom to ask about any puzzles allows anyone to ask for information about the project. Many times, people will go about their work without understanding how the pieces of the project fit together. Puzzles—actions or events that don’t make sense to everyone—might derive from bad ideas or from simple oversight. Conversely, they might be clues identifying misunderstood goals, or great but poorly communicated ideas. Because there are some questions that won’t be answered (such as “When are we going public?” or “How large was Fred’s raise?”), empowerment does not necessarily mean getting the answers to all questions, but rather means being able to ask for information that helps you do the job.

The freedom to talk about whatever is coming up for you allows people to talk about feelings of excitement, happiness, concern, fear, uneasiness, discomfort, or interest, for example. In many environments, it is neither easy nor encouraged to talk about feelings, even though such discussions can provide crucial information about the project. I use the phrase “whatever comes up for you,” instead of the word “feelings” to disarm the hesitancy some people have with discussing their workplace feelings.

The freedom to say that you don’t really feel you have one or more of the preceding three freedoms is listed because people make mistakes. If managers are under stress, they may not respond well to someone exercising one of these freedoms. Or, when someone abuses a freedom—using one at the wrong time; using one to embarrass, distract, or delay; or even using a freedom to complain, for example—the natural reaction on the part of management may be to discount, ignore, or punish the behavior. Whatever the case, the fourth freedom reminds us that all parties need to discuss the freedoms, learn how to use them, and learn how to respond appropriately to someone else using them.

Applied to Retrospectives

I use the “Four Freedoms” wherever I see a need for them. Pre-work and one-on-one interviews can give you clues about trouble spots. In some cases, I may decide to offer the “Four Freedoms” to one individual, but more often, I offer them to an entire group experiencing unintentional disempowerment.

A True Story

All the testers in the quality-assurance group submitted pre-work that suggested they were disempowered. I telephoned each of the testers and arranged to have dinner with the entire group before the retrospective started. During the dinner, I asked what kinds of topics people hoped would be covered. As the discussion proceeded, I stated that I would not be responsible for bringing these topics to light; the testers would need to speak out. I further commented that I would be willing to state my observation that a number of topics, which previously had been discussed privately, had not been brought up. In response to this comment, the testers explained that discussing those topics wouldn’t be safe.

I then offered the “Four Freedoms” and asked group members to tell me what would make them feel comfortable enough to exercise their freedoms. “Permission from the project manager!” they all replied. Later, I asked the project manager for permission, which he immediately granted. Almost as an afterthought, he commented, “I’d love it if the testers would start speaking up. I don’t know why they don’t.”

During the opening session of the retrospective, I added the “Four Freedoms” to the statement of ground rules and then asked the whole community—testers, analysts, and developers alike—to agree to try them. They willingly agreed, but during the following days, there were a few times when I had to encourage the use of the freedoms. By the end of the retrospective, however, a new norm had been established. The experience began an organizational tradition of proactive testers that continues today.

I use the “Four Freedoms” method in situations such as the preceding, but I also may elect to use it when a “Session Without Managers” Exercise is requested. This request suggests to me that the work environment is one in which some people feel they don’t have their four freedoms. When the “Session Without Managers” is scheduled, I introduce the “Four Freedoms” as ground rules to be used throughout the retrospective. This allows people to practice the freedoms during the time that I’m available to keep discussions safe and on track.

References for Further Reading

Gause, Donald C., and Gerald M. Weinberg. Exploring Requirements: Quality Before Design. New York: Dorset House Publishing, 1989.

The discussion of the art of being fully present, which appears on page 140, was instrumental in my discovering what I call the “Four Freedoms.” However, my discovery came about because of my misinterpretation of the material! Nevertheless, the positive result was my invention of this method.

Satir, Virginia. Making Contact. Berkeley, Calif.: Celestial Arts, 1976.

Satir discusses five freedoms that are the natural birthright of all human beings. Her freedoms do not parallel my “Four Freedoms,” but it will be obvious to students of Satir that I was influenced both by her freedoms and the community-building tools.

The “Understanding Differences in Preferences” Procedure

During a retrospective, differences in the way people go about their work will become apparent. Type theory fosters the study of these differences to uncover patterns to enable us to better understand and appreciate each other. While there are numerous systems that explain differences in people, one of the most researched and validated is the Myers-Briggs’ Temperament Types system.

Basic Concept

Myers-Briggs is a system that studies our natural preferences for problem solving. Using this system, we look at four aspects of problem solving and identify the preferences we have. For example, as we search for a solution to a problem,

1. Do we prefer to interact with others, such as in a brainstorming session, or do we prefer to work solo, with only our thoughts to concern us?

2. Do we prefer to acquire information relevant to solving the problem through use of our five senses or by relying on our intuition?

3. What filters do we use to sift through all the information we have collected about a problem that help us identify important information and lead us toward a solution? Do we prefer abstract concepts (theories, logic, and the like) or are we interested in interactions among people (relationships and feelings)?

4. How much information do we need to support a difficult decision and how comfortable are we before and after the decision is made? Do we prefer to seek closure or to keep options open as we collect more information?

The Myers-Briggs system looks at preferences, not at skills and ability. Presumably, most people have the skills and ability to problem-solve from any of the preferences mentioned above. However, for each of the four scenarios each of us prefers one of the two possibilities.

Given that we each have our own preferences and that only rarely are we aware of other people’s preferences, it is easy for us to assume that everyone goes about solving problems in the same way we do. At play during group problem-solving sessions and affecting team interactions, these different preferences can cause interesting conflicts.

A full discussion of Myers-Briggs is beyond the scope of this book, but this brief introduction should alert you to the importance of the material. I encourage you to study it as thoroughly as you can.

Applied to Retrospectives

As I observe the community, I use type theory to help me understand why participants may not be working well together. Typical type-related situations include

• An entire team is composed of one dominant type, and regularly misses opportunities to solve problems because of the limited number of problem-solving approaches available to it.

• Most of a team is composed of one type, but includes a few disenfranchised individuals whom the majority does not understand.

• A team is composed of two subgroup types, each with its own preferences; neither understands the other’s behavior.

By understanding the behavior type that a team has adopted as its natural problem-solving approach, I can tailor my assignments to take advantage of the team’s preferences, or to help its members try a new approach. For example, if a team’s natural preference is to work in a brainstorming session, and I want to help members try a different approach, I ask them to write instead of talk.

Here is another example. If some members prefer to seek closure and others need to keep their options open until they’ve had the chance for further reflection, I adapt exercises to identify “candidate” solutions, and then tell the group that we will revisit each possible solution later, choosing one after we have had a chance to absorb the details of each option.

Even though my job is to facilitate a retrospective, not to fix a group, I may offer suggestions on how a group might improve staff relations. In communities in which Myers-Briggs has been introduced, I may use Myers-Briggs vocabulary to explain baffling interactions. Type theory is well known in Personnel/Human Resources departments and it is possible that the community has been introduced to it. However, it is rare for casual students of the system to remember the details of type or terminology, or to have mastered it.

A True Story

A team I worked with was composed almost entirely of people who preferred to keep their options open. They had long discussions that looked at all aspects of a topic, and frequently returned to previous discussions to be sure they were on the right path. However, one person on the team preferred to seek closure, and was frustrated by discussions that went on seemingly forever. I asked team members to assign the job of timekeeper to that person, and suggested that they all work together to design ground rules for timekeeping.

They formulated ground rules, as follows: At the beginning of each discussion, they would agree on how long it would last; when the time was up, the timekeeper would interrupt. Team members would then either close the discussion and reach a decision, or determine what else they needed to do before they could reach closure. They would then set a new time limit.

Team members continued to use their system after the retrospective was over. It became such a habit that when the timekeeper went on maternity leave, she left the team with a kitchen timer to use until she returned. They laughed at the joke, but a few days later they needed to use it!

References for Further Reading

Keirsey, David, and Marilyn Bates. Please Understand Me: Character & Temperament Types, 4th ed. Del Mar, Calif.: Prometheus Nemesis Book Co., 1984.

Keirsey and Bates do an excellent job of introducing Myers-Briggs Type Indicator and Temperament Type theories. Their book includes discussion of how these types influence leadership as well as of how they apply in day-to-day interactions with family and friends.

Kroeger, Otto, with Janey Thuesen. Type Talk at Work. New York: Delacorte Press, 1992.

This is a good book to read after you’ve read Keirsey and Bates. It addresses using type theory in the workplace, including ethical uses and abuses. The authors include suggestions on how to work with people of different types and how to build an effective team.

The “Ingredients of an Interaction” Procedure

Communication can go astray for all sorts of reasons. A listener misunderstands a word, remembers a similar conversation from the past and misinterprets the new message, or concludes how the message will end before the speaker has even finished. The list of reasons for communication problems is endless. In a retrospective, communication becomes more difficult if listeners are under stress; their listening skills may flag or collapse entirely. To be effective, a facilitator must first recognize that a message has gone astray and then know how to get the discussion back on track. One way I do this is by identifying and utilizing what I call the ingredients of an interaction.

Basic Concept

Before I reveal the procedure, let me provide a bit of background, which comes from both Virginia Satir and Jerry Weinberg. In the four volumes of Quality Software Management, Weinberg interprets Satir’s Interaction Model for a software engineering audience. Volume 2, especially, uses the model to show how a listener passes a message through several stages before he or she can fully understand and respond to it. At each stage, the listener engages in important analysis of the message. Weinberg’s treatment of the topic is comprehensive and edifying—and might well be read in its entirety—but I have developed a condensed and paraphrased version to use as a facilitation tool, as follows.

• Stage 1: Intake. The listener analyzes what he or she saw and heard about the message.

• Stage 2: Assign a meaning. The listener determines a meaning using the analysis from the intake stage.

• Stage 3: Determine a feeling. The listener develops a feeling in response to the message (for example, he or she feels hurt, disappointed, proud, surprised, confused, or some other emotion) based on intake and meaning.

• Stage 4: Identify a feeling about the feeling. After the listener has identified the initial feeling, he or she reacts to the feeling. For example, if the listener has been paid a compliment and feels proud, how does he or she feel about feeling proud? Embarrassed, ashamed, or complimented are all possible emotions and these may color how he or she responds to the message.

Each of the four stages adds to the process of how a listener understands a message and prepares a response. Messages become confused when a listener either misinterprets or skips one or more of the four stages. Success in the final stage, shown below, is dependent on the first four stages of analysis.

• Stage 5: Develop a response. The listener formulates a response. If the listener has high self-esteem, and hears a message that is confusing, he or she probably will ask for clarification in order to discover whether any part of the analysis is incorrect. But if the listener has low self-esteem, his or her response may be inappropriate, confused, or ineffective. Such a person may feel unsafe, showing this distress by perhaps becoming either combative or uncharacteristically quiet.

As facilitator, you can use the preceding five-stage model to help redirect communication that has gone astray. If someone responds in a way that doesn’t make sense, stop and ask what might have happened. Perhaps the listener processed the message incorrectly, but in the most extreme of conflicts, you can find out exactly what’s happening by stopping the dialogue, asking the speaker to repeat the message, and walking the listener through each of the five stages. In such a case, be careful to document the processing and explore alternative conclusions with the listener. I don’t intervene in this fashion very often, since my job is to facilitate the retrospective, not to fix individual listening skills, and I generally avoid direct and lengthy intervention. Instead, I use the five-stage model for my own understanding, and find other ways to resolve miscommunication among team members.

References for Further Reading

Satir, Virginia, John Banmen, Jane Gerber, and Maria Gomori. The Satir Model, Family Therapy and Beyond. Palo Alto, Calif.: Science and Behavior Books, 1991.

Satir developed a complex model for understanding what goes on in another’s head. Satir’s Interaction Model explains feedback loops, family rules, and covert and overt responses based on levels of self-esteem. Written for an audience of fully trained family therapists, Satir’s work is brilliant but decidedly difficult. I recommend that it be tackled after the Weinberg text listed in the next entry.

Weinberg, Gerald M. Quality Software Management: Vol. 2, First-Order Measurement. New York: Dorset House Publishing, 1993.

In this book, Weinberg develops a model to explain Satir’s work in the context of software management.

The Satir Interaction Model is such an important tool for understanding communication that most of Weinberg’s book is dedicated to its many facets. I use Weinberg’s material not just in retrospectives but throughout the software projects I lead. When you think of all the possible communication that occurs during a software project, and realize the implications if any of it goes astray, you will understand why I believe all facilitators should master this material.

The “Congruent Messages” Procedure

A retrospective provides the opportunity for a community to share stories about a past project. Many of these stories are easily told and easily received, but a few are exceedingly difficult. They are difficult because they involve pain, frustration, fear, and other emotions that make people feel weak and vulnerable. When these feelings arise and our messages are adversely affected by our emotions, we may communicate mixed messages, which have overtones that can compromise the success of a retrospective. It is important for a facilitator to recognize these inappropriate messages, to measure the resulting tension among group members, and to intervene in order to help the speaker reword his or her message so that it is accurate and likely to be understood.

Basic Concept

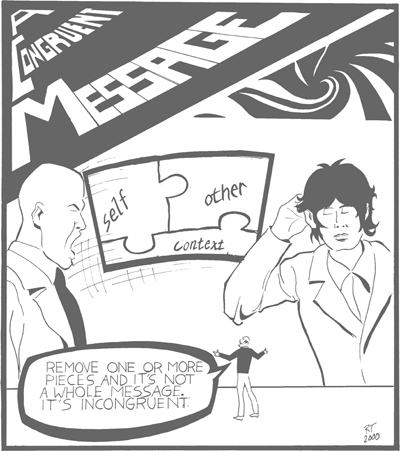

Virginia Satir’s writings describe effective styles of communication as congruent and styles that cause difficulty as incongruent. Satir uses the word “congruent” for messages whose content matches the speaker’s thoughts and body language.

According to Satir, a congruent message has three components, which Jerry Weinberg calls Observer Positions in the Quality Software Management series. In the following, I summarize these components—positions from which to observe what people need to work on in a conflict.

1. Self is the position that honors your right to think and feel as you do about a situation.

2. Other is the position that recognizes that another person, who is receiving your message, also has the right to feel and think about a situation in his or her own way.

3. Context is the position that enables you to share the details of the situation as accurately and as honestly as possible.

To illustrate the effect of congruence, let’s imagine that the following message is delivered during a retrospective by a testing specialist talking to a software developer:

“When you gave us Release 1.0 of the new system, it had not been entered into the configuration management system—pieces of the system resided on several programmers’ machines. These pieces were continually changing, as last-minute features were added.

“As a result, we tested software that was obsolete. We were hurt to find out that we had spent our limited time identifying defects that had already been removed, and that we were testing code while at the same time you were introducing new defects. Our defect reports were ignored, and the effort we spent testing was wasted. It made us feel as if our jobs were pointless.

“I understand that you need to add as many features as time allows, but we need a more disciplined change process from you. I want to talk about what is possible.”

In this exchange, the Self was included when the speaker explained how the testing team felt about wasting its time. The Other was included by the speaker’s recognition that the development group needed to add features at the last minute, and by the invitation to discuss what was possible. The concept of Context was included when the testing specialist described having problems with the software change process.

Incongruent Messages

In addition to the three components, the work of Virginia Satir identifies four common styles of incongruent message. Each of these ineffective message styles occurs because one or more of the three components of a congruent message has been left out. Note that it’s not specific words that are left out, but rather the components of Self, Other, and Context. Because Jerry Weinberg also treats this topic well (see especially Quality Software Management, Vol. 3), I’ve compressed his wisdom with Satir’s to derive my version.

Style 1: Blaming. If the Other component is left out, the message becomes a blaming style of incongruent message. The message might take the following form:

“You sure made our lives miserable when you gave us Release 1.0. While we were working overtime to make sure that the software was the best it could be, you were changing all parts of the system. The software was not in the configuration management system, so you couldn’t even tell us what had changed! There was no way we could know what needed to be tested again, or to know what defects you had already repaired. You made us waste our time, and we don’t like it.”

This message was created with no awareness that software developers have any responsibilities other than to keep testers happy. It does not include an offer to work together to try to find common ground between the different positions, goals, and needs.

A blaming style is ineffective in many ways. The message above might result in the developers using the configuration management system, but at a cost. The developers may react to the blamer by trying to get even or by withholding information during further interactions to avoid being blamed again.

The message might also cause the software developers to take a stand to defend their decision not to use the configuration management system. In such a case, we would be left with two polarized groups fighting about configuration management, and demonstrating no interest in working together to improve their software process.

Style 2: Placating. Another kind of incongruent style involves leaving Self out of the message. Here is an example:

“It was very difficult to test Release 1.0. Things kept changing and we were not very good at knowing what we should test and what we should retest. The software developers have such an important job adding all the features they can before the software ships. We understand that they don’t have time to use a configuration management system. I guess we need to do something different in testing.”

In the placating style of incongruence, the speaker ignores all of his or her feelings and thoughts on the subject, and delivers the message so that it will not upset the listener. In so doing, the speaker appears to be accepting total responsibility for a situation when it should be shared.

A placating style is ineffective because it leaves listeners with the impression that they don’t need to do anything about the situation. They conclude that the speaker will take responsibility for solving the problem.

In the message above, the speaker is hoping that the software development group will realize its foolishness at not using the configuration management system and will volunteer to change. This type of change almost never happens.

Style 3: Super-Reasonable. A third style of incongruence, which I see quite often in the high-tech community, is called super-reasonable. In this style, both Self and Other are left out of the message. The only thing left in the message is Context. This yields a message that sounds like it came from Star Trek’s Mr. Spock. For example:

“It is known that the lack of using a configuration management system yields difficulties for a testing function. These difficulties include wasted testing resources and missed opportunities to discover defects. It is estimated that the cost to this project was an efficiency loss of 61 percent.”

A super-reasonable style avoids discussion of anyone’s feelings or position. The message includes facts and nothing else, often containing statistics that are not particularly accurate and that provide no truly useful information. There is no suggestion of what needs to be done.

This style is ineffective because, after the message has been delivered, no one knows what to do next. The author of the message hasn’t given the recipients a clue about what he or she thinks should happen, nor has the author invited the recipients to discuss how to resolve the problem.

Style 4: Irrelevance. The fourth style of incongruence involves shifting the topic away from the real issue. In this case, Self, Other, and Context have all been removed from the message. People who are really good at this style often turn it into humor, and may be appreciated because they help the group avoid talking about the difficult issues. An example of this type of message follows:

“This project really required us to be quick on our feet. Things were changing so fast that I felt as though I were a one-armed contestant at a greased-pig competition. I tell you, there were times that I just loaded up a battery of tests on every version of software I could find just to make sure that something got tested. You know where I ran those tests? I put them on the VP’s new top-end machine. I don’t think he even noticed the degradation in performance.”

In this style, nothing is mentioned about the real problem. The audience might enjoy the digression but nothing of substance was discussed. We did not learn what the speaker really thinks (Self), the problem of the configuration management system was not raised (Context), and the listeners were not invited to discuss or think about the problem (Other).

Applied to Retrospectives

Most of the time, people deliver congruent messages, but we all deliver incongruent messages occasionally—it’s part of being human. We do this when we are under stress or when we feel vulnerable.

Because the experience of a failed project and the ensuing retrospective discussion can cause people to lose self-confidence and self-esteem, they may well offer incongruent messages during the various exercises. As facilitator, you need to recognize incongruent messages and help the message author understand the reasons for them. The first step is to help the individual achieve a higher level of self-esteem. This is tricky to bring about, especially if you are attempting to do so in front of peers. Being successful in this endeavor depends on

• the kind of relationship you have built with the person

• the information you know about the person (such as, accomplishments, yearnings, goals) and an assessment of how others see him or her

• the type of incongruent style he or she has chosen

• the topic under discussion

As stated above, my first goal always is to help people reestablish their confidence and self-esteem. I then encourage them to develop a different way of saying exactly the same thing that includes Self, Other, and Context. The best way to do this varies with each person and with the facilitator’s skills, but I find that the following approaches often help to reopen communication channels.

For blamers: A place to begin is to let blamers know that they have been heard. Early in the dialogue, communicate that you are listening to what they are saying, stating that you do not necessarily agree but that you do understand. These people are usually concerned with loss of control. As they discover that someone is listening to them, a sense of control returns and their desire to blame tends to dissipate. The next step is to help them readdress the topic, focusing on the three components of Self, Other, and Context.

For placaters: Placaters may fear exposing their sense of themselves, or may not even be sure that it is okay for Self to exist. Begin a dialogue by delving deeper into the message, and conclude by asking, “What would you like to see happen if you could change the situation?”

For super-reasonables: People who have cut off awareness of themselves or of anyone else are harder to bring back into the present because they have isolated their feelings. As a first step, I try placing my hand gently on a super-reasonable person’s forearm or shoulder. The touch usually startles the person slightly and helps me connect with him or her in order to begin exploring true feelings about the situation from the Self point of view. This experience can lead to a discussion about Other, and then to a revision of the message in terms of Context.

For irrelevant folk: These people want to avoid the situation completely, and attempt to derail the discussion, taking it someplace other than where it needs to go. Try to follow their tangent and, rather than returning immediately to the topic, see whether you can add to the digression. Make it a fun break for a bit, and then find a way to use what has happened as a metaphor for the real issue. Explore the metaphor and then ask how this relates to the topic at hand.

The Incongruent Facilitator

Observing incongruence in others is much easier than observing it in yourself. This fact is important to acknowledge because situations may occur in a retrospective that lower the facilitator’s own self-esteem or confidence. I make a point of frequently addressing how I feel and, if I find myself being incongruent, I take a few moments to get back on track. Some steps that work for me include

• deep breathing, which helps me refocus my attention.

• relaxing tense muscles, which requires me to take a moment to notice tension in my body.

• reviewing past events, which compels me to ask myself, “Why am I like this? What triggered my incongruence? What am I saying to myself about how I’m leading this retrospective?”

• reframing, which challenges me to look for an alternate way of thinking about what just happened. I try to imagine how I would look at the situation if I had high self-esteem and great confidence and I hold onto that image in my mind.

• laughing, which allows me to take a moment to enjoy the fact that I’m human. I remind myself not to take matters so seriously, and give myself permission to be less than perfect.

• making amends, which I do when I can find a way to apologize and share what I want people to know about why I’m being incongruent. I then tell everyone that I’m going to try to rephrase the message.

The concept of congruent and incongruent messages is not an easy topic to grasp, nor is it easy to learn to work with. However, once you have mastered it, you’ll have an excellent tool for assuring that retrospectives stay on track.

References for Further Reading

Satir, Virginia. The New Peoplemaking. Palo Alto, Calif.: Science and Behavior Books, 1988.

This very readable book explores aspects of how people interact. I recommend that retrospective facilitators study the entire book, but point all readers to the discussion of congruence and incongruence in Chapters 7 and 8.

Weinberg, Gerald M. Quality Software Management, Vol. 3: Congruent Action. New York: Dorset House Publishing, 1994.

A major proponent of the idea that, since software is built by people, developers need to understand how people work together in order to build complex systems, Weinberg drives home his point in a book that is equally valuable to retrospective facilitators and software engineers. Volume 3 applies Satir’s models of congruence and incongruence to our common software development practices.