Chapter Eight. Postmortem Exercises

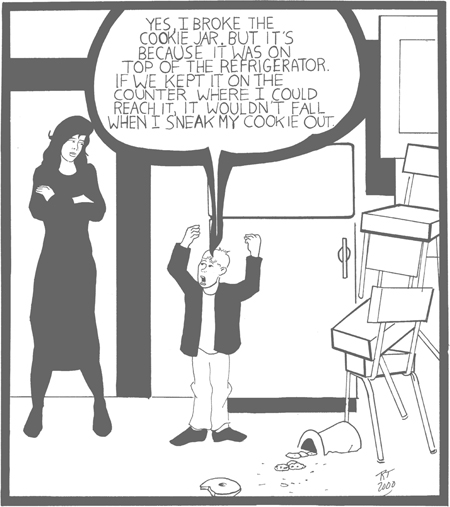

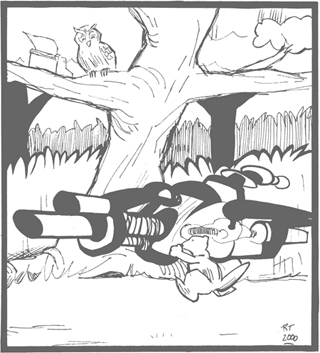

With intermittent flapping of his wings, Owl was hard at work on his Recipes for Life book when he was interrupted by quite a racket. Offering his usual salutation, ″Who? Who?″ Owl looked down to see Beaver passing by lugging a most unusual piece of equipment. ″Beaver, what is that?″

″Oh, hello, Owl. This is my Scubamajig,″ Beaver replied. ″I’m working in the Black Lagoon today. You know Scalely, that retired movie star? He wants me to install a private movie theater in his lair. He likes watching his old movies.″

Owl hooted, ″Yes, I know him, . . . an interesting creature. One of the nicest monsters you will ever meet.″ Growing more curious, Owl continued, ″I’ve never seen you use that tool before. Is it new?″

″Nope,″ replied Beaver, ″I just use this every once in a while. For some jobs, you just need special tools. You see, Scalely’s new movie theater will be under water.″

As Beaver clattered away, Owl wrote himself a reminder to decline Scalely’s invitation to his Return of the Monsters Film Festival. He then began to think about using special tools for special jobs.

The Exercises

The exercises described in this chapter are designed to handle the various circumstances a facilitator may encounter during a postmortem. What makes the exercises especially suitable for use during a postmortem is that each is designed with the goal of enabling the learning that’s possible from failure.

A True Story

Several years ago, my colleague Jean McLendon and I teamed up to lead a postmortem. Emotions were unusually high among team members and their management. Several million dollars had been spent with nothing to show for it, and litigation had begun.

After a long day of one-on-one interviews, Jean and I were still unsure as to why we had been called in, and so the two of us headed off by ourselves to a restaurant to compare notes. It was clear from the one-on-one interviews that project members had thought about the project and could comment on what they would do differently in the future—but there was something odd about what we were hearing. The comments seemed superficial, lessons were not discussed with passion, and no one was using the “f” word. That is, no one seemed to be able to admit that the project was a failure! People knew intellectually that it was a failure, but they couldn’t talk about it as such.

Jean and I realized that this community wouldn’t learn what needed to be learned until people could talk honestly and openly about what it was like to fail. Somewhere in the community’s culture, the discussion of failure was seen as taboo. We needed to change this notion.

Jean suggested that we invite the company’s chief executive officer and its vice president of Information Services to come to the first part of the postmortem so that she could interview them in front of their staff about the presence of failure in their lives and careers, and about what the long-term effect had been. The goal was to establish the value and importance of learning from failure. The executives accepted the invitation, settling in easily as Jean guided the interview questions to be certain all members of the community came away understanding the following points:

• The executives recognized that failure does sometimes happen, and that a failure is something from which people can learn.

• Their project had failed—and failed big.

• No one was going to get fired as a result of admitting that the project was a failure.

• The community had better learn how to prevent such a massive failure next time, because the company couldn’t afford another of that magnitude!

This interview session successfully broke down the barriers that had been preventing project members from openly discussing the reasons why the project failed. By means of the session, implicit permission was given to people to be honest about the issues. The community was ready to examine its failure, and the remainder of the postmortem was charged with discussion of lessons learned.

There was one particularly interesting outcome of this postmortem meeting. Because members of the community could now talk about failure, they could also talk about success. By the end of the postmortem, participants had identified fifteen tasks or procedures that they had learned to do amazingly well, and that could now be considered assets. Before the postmortem, no one had realized that significant gains had occurred in the department alongside the failures. Jean’s idea of interviewing executives about their failures developed into the “CEO/VP Interview” Exercise.

Purpose: This exercise is designed to help participants become comfortable with the idea of talking about failure without feeling shame.

When to use: Use this exercise when members of the community have difficulty with the idea that they have failed, as well as whenever you see evidence of the coping tactics discussed in Chapter 7.

Typical duration: 60 minutes.

Procedure: Ask for a list of the firm’s leaders—those people highest up in the management chain who have the best reputation, the complete respect of the community, and the confidence to be interviewed about their failures in front of their staff. Although you can make the necessary points with only one role model if no other executive seems right for the task, your goal is to find two candidate executives who are willing to be interviewed.

Meet with the candidates and explain that community members need to see someone they respect model the process of learning from failure. Establish a rapport with the executives so that they trust that you won’t embarrass or attack them. The interview is not meant to be an exposé, but rather a dialogue in which empathy and consideration are shown the individual being interviewed. Prior to the interview, ask the executives to outline the stories they want to share, then comment on the stories to give them an indication of the boundaries you’ll observe as you interview.

Start the postmortem with this interview exercise. Jump right into it, postponing discussion of procedural items, an agenda, or any of the other issues in the “Introduction” Exercise until later.

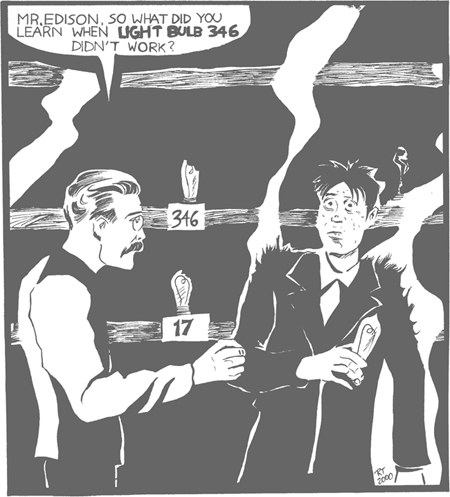

To introduce the exercise, summarize the events that led up to the Challenger failure, citing the details I noted in Chapter 7. Begin a dialogue by saying, “I think we would all agree that the 1986 Challenger Space Shuttle explosion was the result of a failed project. I imagine you would think that many people would have studied the failure and written about it, right? How many books for the general populace would you guess were published within the first few years after the accident?” Field a few guesses and then tell them, “Five—with all but one of those written for children!”

Next, ask, “Why do you think so little was published?” Encourage discussion, and then continue, “I think one reason is because we are uncomfortable talking about failure. How often do you get to talk—honestly and safely—about failure at work before going on to a new project? Is such discussion common? Give me a show of hands if you think it’s common here.”

Comment on the number of hands raised. If there are few hands, then share the fact that this is the way most firms work. Smile and say, “You are in good company.” Point out that failure provides an excellent experience from which to learn. Ask, “Why don’t we discuss failure? Is it because we fear that we might be penalized or even fired?” See whether anyone wants to comment, acknowledging that this kind of frank discussion is difficult.

If more than half of the participants raise their hands, compliment the community, letting people know that their ability to discuss failure is impressive, and assure them they are ready to learn from their experience.

To introduce the executive interviews, begin by saying something like, “I’d like to demonstrate that discussing failure is okay, good, and even the right thing to do. I’ve asked two executives to describe their failures and to tell us what those failures meant to their careers—both short-term and long-term. These people will serve as our role models for open discussion of failure.”

Then, begin the interviews. Ask each executive to describe his or her position in the company, number of years with the company, previous positions held, and so on. Next, ask each to describe a significant career failure. Finally, ask the executives to explain what they learned from the failure and how it shaped their career.

At the end of an hour, thank the executives for their openness, and then call for a break. The break provides time during which information can sink into people’s minds, and gives individuals a chance to comment informally to each other. After the break, start the “Introduction” Exercise.

The “Art Gallery” Exercise

Course: Late in the Readying course or early in the Past course.

Purpose: To help people become comfortable discussing their project.

When to use: Use whenever there are no executives available to be interviewed but the community is not describing the experience using the word “failure.”

Typical duration: 60 minutes.

Procedure: To start the analysis of the group’s failure, I ask natural-affinity teams to find their own space, taking with them a flip-chart pad and colored pens. I tell members of each group to do the “Art Gallery” Exercise by using only the right side of their brains, that is, without talking. My instructions are: “Collaborate to draw one picture of what it was like to be on this project. This is to be a picture derived without any discussion.”

As each picture is completed, I ask the artists to discuss their work among themselves and then to add a title to their picture. The next step is to place the pictures side-by-side on a wall and invite the entire community to gather around. The artists from each natural-affinity team are then asked to describe their works of art. After they have presented their work, I ask other members of the community whether they have any questions. As the discussion continues, a composite picture begins to emerge from which participants can compare the experiences illustrated by the various groups’ drawings.

What we are doing in the “Art Gallery” Exercise is beginning to tell the stories of the whole project. The drawings provide a great way to introduce the idea that this project may be seen from many different viewpoints. The session opens up the chance for someone to take a risk anonymously, or to depict some painful aspect of the project, perhaps with a bit of humor. The drawing session provides a nice way to let people ease into telling their story.

Background and theory: In her breakthrough book, Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain, Betty Edwards explores ways to tap underused areas of the brain. The “right side” designates the part of the brain that allows one an awareness of concepts to be sensed without the use of words. This side of the brain does not operate on use of reason or facts, yet it aids us in reading conclusions intuitively. It provides a rich source of creativity.

Edwards explains that we can access this valuable part of our brain through drawing. The results often astound us as we let our left side of the brain analyze and put into words what was produced by our right side.

This exercise begins as a non-talking exercise because we want the right side of the brain, the nonverbal side, to be in control. It is a group activity that uses natural affinity to aid mutual suggestion and thus deeper exploration.

Once the drawing has been produced, the activity of finding a title for each picture invites left-brain analysis through discussion among the collaborators. Words are now used to describe the often surprising pictures, and a new understanding of the project experience can begin.

The “Define Insanity” Exercise

Course: This exercise may be used late in the Readying course, or during the Past course, especially as a substitute for the “Session Without Managers” Exercise, if such a session is requested as part of the postmortem. I’ve also used this exercise with a community that was considering a postmortem but which feared that such a session would turn ugly. This exercise is especially effective when used to demonstrate that a blame-free review can be conducted.

Purpose: Some groups have experienced not just one but a series of failures. Most likely, their software process, professional practice, and management style all ensure failure. Individuals in such groups feel like victims trapped in an impossible situation. I use this exercise when I see a series of failed projects with participants who say they feel like victims. For such people, the exercise helps them recognize that they have power and can effect change.

When to use: As needed.

Typical duration: One to two hours.

Procedure: This exercise has several steps.

Step 1: Provide a working definition of insanity. Tell the community that you have your own definition of insanity, and you want to share it. Write the definition on a flip chart:

Insanity means doing the same thing you did in the past but expecting different results.

Step 2: Ask participants for examples of insanity from their own project experience. Ask whether anyone has experienced the kind of insanity described in the definition. Then ask for examples of things that people keep doing while expecting new results. List each example on a flip chart. Ask enough questions so that everyone understands what each example is about. You may be able to combine several ideas into a single item on the flip chart, or you might need to break an overly general concept into several smaller, more concise statements. As people exhaust their examples or as you finish off about two pages, close the discussion and title the list “Don’t Do Again.”

Step 3: Encourage discussion of alternatives. Move to a second flip chart and label a clean sheet of paper “Do Differently Next Time.” For each item listing an example of insanity, have the community find a counteraction that it can agree on for next time. Check that each “Do Differently” item is realistic. If not, help people identify a good alternative.

Step 4: Select follow-on exercises to complement the identified goals. Use the results of this exercise to select the contents of the rest of the exercises you run. In the “Develop a Time Line” Exercise, you will be able to skip over some of the obvious lessons learned because they are already on your “Do Differently Next Time” list. In the Future course, you can include these lists as part of the exercises for “Cross-Affinity Teams,” “Making the Magic Happen,” and “Change the Paper.”

A True Story, Revisited

If this exercise sounds a bit familiar, it should. The team members described in the story told in the “Change the Paper” Exercise in Chapter 6 used the results of their discussion to make posters. Recall that that team’s members had listed “Don’t build a system the size of an elephant” and “Don’t use arbitrary dates as goals” as reminders of what not to do next time. However, for that team, finding and listing counteractions seemed impossible as the features required and the time allowed were dictated by upper management. I reminded team members that these lists can be thought of as a “Declaration of Independence from the Past,” stating, “Let’s write down what we need to do differently next time, and then figure out how we can make such a project happen.” After further discussion and brainstorming sessions, they decided on two important actions:

• Do build a mosquito—very small, very effective, very noticeable, with a short life.

• Do develop our own schedules and set our own goals.

With these counteractions noted on the “Do Differently Next Time” flip chart, we set about to see how we might proceed—following the goals set by upper management but working according to the developers’ own (sane) terms. Team members decided they could build a piece of the required system and deliver it in two or three months, rather than attempt to build the entire system in the dictated (but impossible) nine months.

They prepared a proposal for management, pointing out that after the series of failures, they needed to try something small. The developers stated that they would be in charge of identifying which piece of the overall system they would build, but that it would provide significant utility to their users. By the end of the postmortem, they had developed a convincing plan, which management accepted.

It took team members five months to build the selected system piece, delivering about one third of the entire requested system. Users were now happy and encouraged, excited that an important piece of the desired system was delivered early!

During the five months, a phased approach to software development had become part of the management style, and plans for Phase Two indicated that the team would build the second third of the system within the next three months. Efficiency was up, process mastery was up, morale was up, and user confidence was up.

Because of the success of Phase One, and because high-level management had confidence that Phase Two would be delivered ahead of the original nine-month schedule, no one truly cared that the unrealistic, dictated schedule was being ignored. Instead, team members were left to build incrementally and upper management focused on exploring the candidate features of Phase Three and procuring third-phase funding.

Four months after the completion of Phase Three, promotions and company-wide recognition were given to those who “built a mosquito when the users asked for an elephant, and figured out how to build it smaller and faster than requested.”

Theory and background: By providing a definition of insanity, and then by asking the community to give examples of insanity using that definition, a facilitator can promote a safe discussion of software process flaws without the conversation degenerating into an attack on any one person. If it is clear that the discussion is not about individuals, it easily becomes an analysis of the software development process. In cases in which participants seem resistant, assure them that, since the team as a whole has had a series of failures, it is certain that the problem is the group’s way of working, not the fault of particular individuals.

The first step, asking team members about their particular insanity, helps focus the discussion on what has been going on and what habits are problematical. The second step, labeling the insanity as “Don’t Do Again,” is a subtle step toward causing the community to change. The community has agreed that these practices are insane. The act of labeling the list serves the purpose of defining and naming the goal in a way that no one can argue against. In Influence, a book on marketing trends and methods, Robert Cialdini calls this persuasive effect social proof—that is, a group will follow social norms if they are norms the group has established.

The third step generates the “Do Differently Next Time” statements and allows empowerment to occur. The community gets to dream of an alternative way of working that avoids the insanity. This new vision then feeds the Future course activities. The “Do Differently Next Time” list breaks a difficult task into manageable pieces. It also serves as a reminder and an anchor back to the moment when the community decided to stop the insanity.

The “Make It a Mission” Exercise

Course: The Future.

Purpose: This exercise is intended to transform a failed experience into a mission to change the firm’s software development process, to establish pride in the ability to learn from mistakes, and to help all members of the community become experts on how the firm’s common software development process must change.

When to use: Select this exercise when discoveries found during the postmortem have widespread implications for the firm.

Typical duration: Two to four hours.

Procedure: Simply stated, a postmortem could be used to launch a revolution. It can excite project members so much about what they learn that they want to carry their message throughout their organization. Passion and purpose to change the company can easily grow out of a team’s analysis of failure. As a facilitator, you may have to help team members translate this dream into reality.

In this “Make It a Mission” Exercise, you are teaching people how to become activists—how to work to change a community. Because this topic is too complex to cover completely in this handbook, I refer you to the works of Judith L. Boice and Saul D. Alinsky for additional information (see the reference section at the end of this exercise). I can, however, make some suggestions here for you to convey to your community:

• Have a clear mission. Establish agreement about your overall goal by developing a mission statement.

• Remove ego from the message. Present the message because it is the right thing to do, not because it is good for your career.

• Cultivate vision, persistence, confidence, and optimism. Demonstrate each of these characteristics as you begin to take the message to the rest of the organization. Make it a regular practice to measure how well you are doing in each of these four areas.

• Plan to educate, and present your message often. Adults can learn, but most need to hear the message many times in many different ways. They need to reflect on the message as they consider their own experiences.

• Invite others in the company to join you. A grass-roots movement is more likely to succeed if many people join in and deliver the message of change.

• Create a newsletter. Every active change movement needs a way to communicate—a clearing house through which announcements can be made, to encourage continuation of the learning and thinking process, and to focus a community. A print or electronic newsletter is just such a clearing house. Whether it arrives directly in the hands or on the screen, either type is preferable to a Website, which is passive and only works if people actually visit the site.

• Be inclusive of others’ ideas. Many activist efforts fail because of infighting. From the start, show by your inclusive attitude that all ideas are welcome and a difference of opinion is okay, as long as everyone is working to accomplish the mission statement.

• Be a respectful change agent, rather than a zealot. Discuss the issues, listen closely in order to understand others’ opinions, search for common ground, and adopt a position that fits both parties’ ideas—or, agree to disagree.

• Live your own message. No matter what changes you may or may not effect throughout the company, use what you have learned to modify how you work.

Change-effecting activities for team members to explore as part of planning their mission might include

• making a presentation to top-level management on ways to prevent future failures

• developing a presentation to be given to the entire firm

• writing a regular column in the company newsletter

• creating a company-wide committee to address change in the software process

• establishing a long-term company-wide initiative to investigate issues discussed in the postmortem

• establishing an annual in-house conference on software process improvement

A True Story

As its postmortem proceeded, one team I worked with became increasingly excited about what it had learned, and wondered how it might spread its mission throughout the company. One senior programmer offered to call the company’s CIO, a long-time friend, to talk him into visiting the postmortem on its final day. Although the fact that the project had failed was common knowledge among corporate management—so much so that most of the executives were distancing themselves—the CIO trusted his friend and agreed to a fifteen-minute visit.

Expecting a somber mood when he entered the room, the CIO was visibly startled by the high level of positive energy. Several team members enthusiastically ushered him over to the time line and seismograph. He asked some of the participants to explain the significant points and events, and then sat quietly as another group presented a list of nearly two-dozen lessons mastered during the project. A spokesperson for the group explained that knowing any of these lessons during the project either could have prevented the failure entirely or would have made the issues obvious in enough time for people to take action and save the project. Group members pointed out to the CIO how the rest of the company had not yet learned these lessons, and was still susceptible to failure.

The CIO reflected for a half-second before exclaiming, “You mean I could be sitting on another one of these failures right now?” Everyone nodded.

At the CIO’s behest, members of a third group then presented its plan for taking the postmortem lessons company-wide through a series of seminars. They explained that the seminars would be the first in a series of quarterly symposiums presented by in-house staff dedicated to improving software process and quality. The group talked about its wish to form committees to review and improve software practices, to provide relevant training, and to initiate best-practice scouting trips to other local firms to compare notes.

The CIO forgot his quarter-hour limit and spent the next several hours asking questions, contributing ideas, and identifying people he wanted the group to contact. When he asked about cost, no one was able to give him firm numbers, but he remained positive, responding, “I like what I’m hearing. Work up some numbers and run them by me. Assuming we go ahead with this, I’d like a monthly status report on this initiative. And, get in touch with me if you need my help.”

To further prove his commitment, the CIO invited the entire team out for dinner, continuing the discussion well into the evening.

Background and theory: The family therapist Virginia Satir has been quoted as saying, “It’s not the event that matters, but your reaction to the event.” One classic example illustrating the truth in Satir’s statement occurred in 1980 when then-President Jimmy Carter realized that the attempt to free the Americans held hostage in Iran had failed. He called a press conference to detail what had happened. In the weeks and months to come, the failed attempt was examined, reexamined, analyzed, and reanalyzed, producing documents filled with information to assure that future attempts made under similar conditions would be successful. President Carter could have tried to deny the action and cover up the truth. However, he chose the response that helped him and the nation grow and learn.

The courage President Carter showed by honestly discussing the failed attempt, and his desire to learn from it, gained him a vast amount of respect. His actions lent credence to the idea that an individual who has suffered a failure has the opportunity to become a respected advocate for change.

A group earns respect when it sponsors honest discussion of what happened, why it happened, and what to do to make sure it doesn’t happen again. Publicly sharing the lessons learned with the larger organization transforms the failure into an opportunity for growth. Effective in the political arena, this practice also works well in a business environment in which staff members fear that failure will be punished. A public and honest accounting that helps educate the entire firm can counteract any impulse to punish. The message shared needs to be bold, courageous, and honest, saying, “Don’t do as we did. Let’s all learn from our experience and make sure that nothing like this happens again.”

References for Further Reading

Alinsky, Saul D. Rules for Radicals: A Primer for Realistic Radicals. New York: Random House, 1971.

Although it does not teach a person how to become an activist, Alinsky’s book deals with ways to guide a group of activists toward a common goal. Throughout his professional life, Alinsky helped establish trade unions and was involved with many other activist efforts. His book contains sage advice for establishing a culture that will help activists achieve their goal.

Boice, Judith L. The Art of Daily Activism. Oakland, Calif.: Wingbow Press, 1992.

Boice introduces readers to a comprehensive way of living life as an activist. Her work is gentle yet strong and somehow convincing. She writes that activism starts with inner work—changing ourselves—and then she addresses changes she as an activist would like made. Read her work to see how she gets her message across, even if you may not agree with her position.

Branden, Nathaniel. The Six Pillars of Self-Esteem. New York: Bantam, 1994.

Branden explains the complex concept of self-esteem simply, first discussing the importance of self-esteem, next detailing each of his “pillars,” and then finishing with discussions directed at parents, teachers, and other authority figures. His advice to managers who want to promote self-esteem in the workplace applies well to the facilitation of retrospectives.

Cialdini, Robert B. Influence: The Psychology of Persuasion. New York: William Morrow & Co., 1984.

This text is aimed at marketers, and explains how to influence customers. When I first read the book, I thought the material bordered on the unethical as it seems to describe ways to trick people into buying. I later decided that knowing about the art of persuasion is useful to facilitators, whose job it is to create events that persuade members of a community to change their ways of operating. The key to ethical use of persuasive material in facilitation is not to define what changes need to be made, but to let the community define what those new ways are. That is, the facilitator’s job is to help people get moving in a direction of their own choosing. The “Define Insanity” Exercise is effective because of its use of persuasion. Understanding this, I no longer view Cialdini’s advice as outside a reasonable code of ethics.

Kübler-Ross, Elisabeth. On Death and Dying. New York: First Collier Books, 1969.

This book, one of several Kübler-Ross wrote on the subject of dying, is the classic that introduces her research and theory to a mass-market audience. Although her scientific work has often been misinterpreted by lay audiences, this book should be read by all facilitators.

Myers, Ware, “Leading from a Powerless Position,” IEEE Software, Vol. 13, No. 5 (September 1996), pp. 106–8.

In this article based on an interview with me, Ware Myers explores how facilitators can be taught to use the change agent tactics of Gandhi in the workplace setting.