Chapter Seven. Leading a Postmortem

Perched high atop a tree late one night, Owl watched as Singed-Tail returned home from a hunting expedition. Rather than announcing his return with his usual barrage of howls and yelps, the wolf crept furtively into his den with the stealth of a hunter trying to escape the notice of his intended prey.

More curious than ever, Owl could barely contain himself until the next morning when he knocked on Singed-Tail’s door. His knock was greeted with a growled response, “Get outta here. I ain’t seein’ nobody.”

“It’s Owl. I just wanted to hear how your hunt went.”

The wolf barked, “Went fine. Just don’t wanna talk about it.”

Owl pushed for Singed-Tail’s reason, “Why’s that?”

“Look, maybe we’ll talk sometime—say, after my next hunt.”

“That’s okay.” Owl dropped his voice, “I was a bit worried. As you came back last night, I noticed two yellow stripes running down your back. It looked like you might have been run over by a highway road-crew truck.”

Bursting from his den, Singed-Tail bared his teeth, “Owl, you better keep your beak closed!”

“Don’t worry, my friend. I’m not here to embarrass you. I just thought you might like to talk about what happened. You might discover something to do differently next time.”

“I don’t need your help! I can think things through on my own. Besides, I’m tired of hunting those three pigs; I’m gonna turn vegetarian!”

No doubt the three pigs had bested Singed-Tail yet again. What Owl had observed late the previous night was a humiliated wolf as he returned home from yet another failure. Singed-Tail’s emotions the day after this failure resemble the emotions felt by many project members after a project fiasco. Singed-Tail was embarrassed. He denied that there were any problems. He wanted to bargain for more time before discussing hunting. He was angry and became threatening. He was discouraged and even depressed—so much so that he vowed to stop eating meat. His confidence about his ability to be a big, bad wolf had hit rock bottom.

Overwhelmed by these emotions, the wolf felt too much pain to think about the hunt. Owl, however, knew that it was this very pain that could provide the motivation for Singed-Tail to actually learn better ways to hunt—but he would need to actively review his experience.

It is my conviction that there is no better way to recover from a failed project than to participate in an effective retrospective, one that is truly a project postmortem. In this chapter on failed projects, I deliberately use the word postmortem rather than retrospective. “After death” seems to be the best way to describe a review of the kinds of projects I discuss here—projects that failed, and failed seriously! Failed—as in, $3 million has been spent and there is nothing to show for it and there is no projected date indicating when the system might work. Failed—as in, if the system were used, it could kill people, damage property, or cause the loss of vast amounts of money!

The postmortem provides an invaluable learning experience precisely because a failed project contains many important clues about what needs changing. With clear evidence that the project failed, these clues cannot be ignored. An honest, soul-searching assessment is more likely to result from the postmortem of a failed project than will be revealed through review of a partially successful project. With the latter, people tend to rationalize, “After all, we did deliver something.”

We have dramatic failures such as are described above—in fact, they are all-too common in our business—but not much is written about them, except for the occasional Monday-morning-quarterback analysis performed by an outsider whose purpose is to find fault. It is rare for a team to look carefully and methodically at its own failure to see what can be learned, yet this is exactly what needs to happen. A major project failure doesn’t happen because of one or two wrong decisions, nor is it the fault of one or two people. Big projects fail when all of the following conditions are true:

• Important decisions were made poorly or were not made at all.

• Safeguards that should reveal problems early did not exist or did not work.

• Team members either could not or would not speak up to say that the project was in trouble, or if they did say something, their words were not heeded.

All people-based systems—such as management, engineering, quality assurance, process development, risk analysis, funding, communication, and community protocol systems—and all hiring, firing, and advancement policies contribute in some part to big-project failure. Analysis of failure can initiate significant positive change throughout a firm, extending well beyond the group that experienced the failure. Although the failure may have occurred within only one group, the entire organization’s culture is likely to have contributed to the failure in some way. Therefore, diagnosis of a failure requires a careful and fearless analysis of the entire organization to see what needs to be reengineered.

The best time to review all software development practices is when the memory of the failure is freshest. There are likely to be other potential failures waiting to occur. Why then are so few postmortems held? The following story illustrates the dichotomy between what we think should be and what is.

The Challenger Story

While preparing to facilitate my first large postmortem in 1988, I wondered what best to model failure analysis on so as to make the benefits unequivocal. Researching the topic, I found that a great deal had been written about why businesses or marriages fail, but I wanted an example more applicable to my client’s project, one that would illustrate analyzing failure and growing beyond it. I came across one subject index that cited project-failure analysis in terms of the January 1986 explosion of the Space Shuttle Challenger. The events leading up to the tragedy struck me as important to study. I knew that the National Aeronautics and Space Administration had grounded all space launches immediately following the disaster, devoting the ensuing months to reengineering each process and procedure used prior to the accident, and to reexamining all its policies and practices.

Hoping to find more information, I headed to the nearest bookstore to research how NASA learned from and coped with the failure. What I found astonished me—although there were a vast number of government and scientific documents written on the Challenger explosion, only five mass-market books were listed on the subject. Four of the books were written for school-children to help them cope with the fact that a young teacher had died in the accident. Only one of the listed books targeted the adult market—Challenger: The Final Voyage by Richard S. Lewis—and it was not in stock.

The lack of literature confirmed my belief that people are reluctant to study failure! Self-examination is hard, but I believe we can learn more from studying our failures than from our successes. With our failures, we know something went wrong. With our successes, we wonder how much of what we did was pure chance.

Our culture has taught us about succeeding and winning, but we don’t learn how to lose in a healthy way. From Pee Wee League teams to high-school intramurals to the Olympics, we learn that we are to “bring home the gold.” If we don’t, we feel shame and disappointment. Our culture conditions us to feel this way, but the feeling is only one of many possible reactions. Another way to react is to embrace the failure as an opportunity to learn, saying, “Now I know for sure that I have something to learn.”

Transforming the Failed-Project Experience

The phrase “use of self” is common in the facilitation field but it puzzled me when I was first learning to facilitate and consult. I came to understand that it means using my presence, my actions, my comments, and my responses to elicit healing behavior among people in the community. Because they look to me for guidance, I can affect the attitudes of people with the way I respond and lead.

One key idea the facilitator must convey is that failure is just one possible outcome. The experience of failure is okay to talk about and learn from. It should not carry shame or guilt or blame. It is an experience that should awaken curiosity and a passion to improve. Your goal as facilitator is to establish in the community a sense of pride in the wisdom acquired by a fearless and meticulous review, and a commitment to change.

Leading a truly effective postmortem may very well be the most satisfying work a facilitator can do. Within the span of a few days, a disappointed, fragmented group of people can be transformed into a team with a clear focus and a desire to proceed. Managers who ask for a postmortem usually are people who value learning how to improve more than they fear the repercussions of failure. They are true leaders, worthy of their team’s trust and the responsibility their firm has given them.

As facilitator, you occupy an important position. You may be the first person outside the team to view the entire project. In one sense, you are an authority figure. How much the community accepts you and lets you see depends entirely on you. To help people accept you fully, you need to communicate the attitude that the project is only a failure if the community does not learn from it. Show that you honestly believe that each member of the community did the best he or she could, given what was known at the time. Convey your conviction that by working with team members, you and they will figure out what to do differently next time. Demonstrate that you are capable of discretion and of honest communication, making it safe for the community to share its secrets. See that everyone understands that you are not there to pass judgment, but only to guide community members as they discover what they need to learn. Be a good listener as you help people create an environment within which the project can be explored safely.

Consultants who confuse their customary role of giving advice with their current role of being neutral postmortem facilitators can do irreversible harm by imposing their opinions. When a facilitator ceases to be neutral, participants may feel unsafe and communication will stop. No matter how much you want to give the community answers or seize a teachable moment, don’t do it. Instead, use your experience and your insight to gently lead community members into finding their own answers.

When preparing for a postmortem, assess the community’s mood and current state of mind. Determine whether people have adopted a coping strategy that will prevent a successful postmortem from occurring. When I observe teams that have experienced a recent project failure, I usually see at least one of the following three coping behaviors. These behaviors, which are common among people who feel they have failed, are

• saving face

• grieving over loss

• accepting a lowered self-esteem

Saving Face

A person’s sense of failure may be so great that he or she will feel unable to bear it. One approach people typically use to cope with their sense of failure is called “saving face.” Saving face entails an attempt to preserve dignity in spite of the situation and is an almost instinctive approach people use to avoid feelings of failure. There are numerous face-saving stances but most involve accepting a bit of fantasy as reality. Often, the fantasy makes little sense to an impartial observer while it is clearly believable to those involved. Following are some of the face-saving fantasies that people may adopt:

• Declare the project a success: The team declares the project a success and ensures that no one asks too many questions. There is usually a shroud of secrecy around the project and facts are difficult to determine. Key people on the project might whisper bits of the story, but soon the corporate memory forgets the failed aspects of the project and the manufactured truth gets retold and embellished.

• Establish blame elsewhere: Group members find one individual or perhaps even a few people to blame for the failure. This is odious behavior as the “guilty” party might lose his or her job, or be stripped of responsibilities. Along with their mission to establish who is to blame, people who seek retribution probably harbor a great deal of anger. The truth is that many people feel guilty over the failure of a project, and may move as fast as they can to blame someone else. Of course, the scapegoat is rarely the person who created the problems, but often is the one who put the most effort into trying to solve them.

• Subordinate the project to something “more important:” The group shifts priorities and suggests that the project can “go on the shelf for a while.” People who try this approach contend that the market has shifted, or the customer base has shifted, or other opportunities are now more important, and that, as a result, they need to stop the current effort.

• Purchase a silver-bullet remedy: Team members believe they can find a third-party supplier of a system that will be better and cheaper than the one that has failed. The reality is that this off-the-shelf purchase probably will be less functional than the failed system, or that such a system does not even exist as a product for purchase.

• Claim that the job simply couldn’t be done: Project team members accept that it was an aggressive project, which was good for them to attempt at the time, but which was loaded with risk. They rationalize that, given those circumstances, they couldn’t have been expected to complete it. While this may sound healthy, watch for the next phrase: “Since we couldn’t do it, that proves that it couldn’t be done.” This means that people have accepted that failure was the only possible outcome.

• Hide project demise: During a down-sizing activity, many projects are reduced or canceled as a result of a “difficult but fiscally responsible act on senior management’s part.” The fault is placed not on the project but on economic hard times. The typical scramble that follows, as management looks for projects that can absorb displaced workers, assures that no one asks too many questions about any of the canceled projects.

Even though they are dysfunctional, these face-saving tactics are a natural way for people to rationalize that a failure was a success. As facilitator, you need to understand the state of mind of your postmortem community and make allowances for it. Schedule postmortem assignments according to the group’s frame of mind. Structure your pre-work efforts, early site visits, and selection of exercises to accommodate the community’s current needs and to help people take a more realistic view of their failure—use an approach that awakens curiosity and a passion to improve, and that helps them establish pride in their wisdom while building their commitment to change. Remember: Saving face involves maintaining one’s dignity. Deploying Kerth’s Prime Directive (see Chapter 1) is key to ensuring that people’s dignity is protected while they explore their experience.

Grieving Over Loss

To see how this second coping behavior can take form, think back to the fable of Singed-Tail. Not ready to review his misad-venture despite Owl’s sympathetic encouragement, the wolf reacted by denying his failure, trying to bargain, venting anger, and then by succumbing to a period of depression.

Humans experience these same emotions as the result of a loss. Elisabeth Kübler-Ross, the famous Swiss psychiatrist and noted author of On Death and Dying, researched people’s reactions to loss, studied in the extreme context of facing their own death or that of someone close. Although the loss of a project undeniably is less devastating than the losses Kübler-Ross studied, the software developer who has made serious sacrifices to create a system “no matter what” will have become very attached to the future outcome. If the project is stopped, the developer’s natural reaction can be a grief similar to that associated with death.

The work of Kübler-Ross details five distinct stages that people who are faced with loss move through, sometimes moving sequentially in the order listed here but not always. The stages of denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance are described below in terms of software projects.

In denial, people refuse to believe that the project has failed. In any large community, there will be people who do not believe that the project has really been canceled, who even continue with their work. Others may believe that the project is merely on hold, expecting that it will be restarted in a few weeks. In such cases, my job is to help individuals see reality. After asking them questions about their world view, I use their answers to reveal to them what I observe to be true.

During the anger stage, people may exhibit hostility and even rage. They resent the sacrifices they have made, sometimes to the point of irrationality. Although often considered to be destructive, anger can be therapeutic if vented in a healthy manner. From personal experience, I’ve come across several activities that may mitigate anger—such as writing a no-holds-barred letter (but not sending it), punching a pillow, storming about or yelling in an empty room, or exercising vigorously. Such venting activities lend physical action and voice to counteract emotions stirred up by the anger-causing events that occurred during the project.

During bargaining, attempts at negotiation take place. People plead, “What do we need to do differently to keep this project going?” They ask for another chance. When facilitating a project whose members are in this stage, you are likely to receive weak and flawed assessments designed to demonstrate how close the project is to actually being successful. When I meet someone who is in the bargaining stage, I rarely need to do anything. Bargain-seekers usually come to the conclusion that the strategy will not work. However, sometimes I urge them to write down their assessment, recommending that they provide comprehensive, clearly written estimates accompanied by well-documented reasons. In many cases, the act of collecting and organizing the data is enough to help them discover the weaknesses in their arguments and to move them out of the bargaining stage.

People who sink into a project-related, temporary state of depression will seem to have totally given up. Typically, they feel defeated. They go through the motions of working but feel as if they have too little energy to be truly productive again. When I see people this disheartened, I acknowledge that what they are feeling makes sense to me, telling them that I have been there, too. I ask questions but I don’t give answers. I propose tasks geared to involving them in achievable assignments they can work on throughout the postmortem. I help them begin to think about what would be a good next job—one which they could approach with curiosity and excitement, and one in which they could experience growth and joy.

People in a state of depression may contemplate a career change, but this is usually the wrong time for them to act on their feelings. If you learn that someone is considering a serious change, ask how long he or she has been thinking about it. If it has only been for a short while, urge the individual to take things slowly. When in this state, people rarely make wise decisions.

Acceptance is the stage at which the need for coping ends. Once acceptance of the failed project has occurred, people can get on with their lives and the community and facilitator can get on with learning from the project postmortem.

I use this model of the five stages of coping to help managers understand events in their organization. At the end of a failed project, a firm may choose to break up the team and distribute the people to a number of understaffed projects across the company. Human resource and project managers are likely to make incorrect decisions about what people coming off of a failed project are capable of if they observe people in their coping states. Managers need to understand that these coping stages are not permanent, and that the behavior does not represent what the worker has to offer long-term.

I have watched a number of people whose managers thought of them as poor performers work through the stages of coping during a postmortem and emerge as significant players in the weeks and months to come.

Accepting a Lowered Self-Esteem

Besides exhibiting face-saving and grieving behavior, people whose projects have failed may experience a general loss of self-esteem. Nathaniel Branden, author of The Six Pillars of Self-Esteem, identifies five characteristics common to people with healthy levels of self-esteem.

• confidence in one’s ability to think

• confidence in one’s ability to cope with the basic challenges of life

• confidence in one’s right to be successful and happy

• confidence in being worthy, deserving, and entitled to assert one’s needs and wants

• confidence in being entitled to achieve one’s goals and to enjoy the fruits of one’s labor

In his book, Branden describes how a person’s level of self-esteem impacts his or her rationality, grasp of reality, intuitiveness, benevolence, creativity, independence, flexibility, ability to manage change, willingness to admit and correct mistakes, and ability to cooperate.

Experiencing a failed project can cause people to doubt the way they think, cope, and assert their rights, making them feel less worthy to express opinions or to provide leadership.

The development of one’s healthy self-esteem should be a life-long practice. Whether high or low, the level of your self-esteem is re-set and maintained daily. An event such as a failed project can dramatically affect self-esteem. For most people, a failed project will result in lower self-esteem, but a person who actively works to maintain self-confidence may find that facing a failure head-on helps one move past the failure.

Low self-esteem may be characterized by specific personality traits and moods, such as varying degrees of guardedness, paranoia, intolerance of others’ mistakes, stifled creativity, repression, and an inability to take risks. None of these character disorders is conducive to a successful postmortem.

A further problem is that temporarily lowered self-esteem, if left unaddressed, can become habitually lowered self-esteem. As a facilitator, you have a chance to transform a project team’s perspective and help people learn to deal with failure—an accomplishment that can increase their feelings of confidence and worth, making them productive once again.

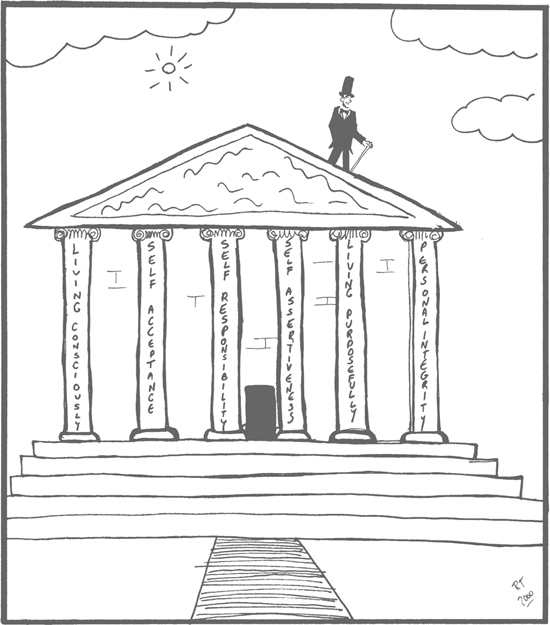

Branden identifies six pillars upon which a healthy self-esteem can be constructed. Paraphrased, the six pillars are

• The practice of living consciously: Become more aware of all that might go on within a project, and do not automatically work as you have in the past simply out of habit.

• The practice of self-acceptance: Accept that you are a human with strengths and weaknesses, and believe that you have something significant to contribute to the project.

• The practice of self-responsibility: Own the results of your actions and choose to be empowered to effect those results.

• The practice of self-assertiveness: Know you have a place on the team and valuable contributions to make.

• The practice of living purposefully: Approach your work and your profession with some greater purpose in mind than simply that “It’s a job.”

• The practice of personal integrity: Exercise a moral creed to align how you think, what you say, and how you act, keeping your thoughts consistent with your actions and words.

As you interact with the retrospective’s participants, look for signs of people coping with lowered self-esteem. Keep Bran-den’s six pillars in mind and employ them appropriately. Weave them into exercises, into your discussions, and into your facilitation. You may have to be the enforcer to redirect actions counter to each of these pillars, but if so, intervene only from the perspective that coping behavior is natural. It is neither bad nor good, but just the way things are.

Exercises that promote self-esteem are useful. For example, the “Artifacts Contest” Exercise and the “Develop a Time Line” Exercise contribute to living consciously. The rule that states “everything is optional” and the “Create Safety” Exercise support self-responsibility and lead to personal integrity. The establishment of natural-affinity teams or cross-affinity teams encourages self-assertiveness. The “Mining the Time Line for Gold” activity and the “Change the Paper” Exercise further living purposefully.

Qualifying to Lead a Postmortem

Given the complexities of a community coping with a failed project, before you accept the assignment to facilitate, you need to assess whether you are fully qualified to lead the particular postmortem. How can you know? Answering the following questions can help you evaluate your readiness.

First, honestly evaluate how much experience you have had leading people under stress and how good you are at it. Are you comfortable facilitating sessions in which emotions are strong? Are you capable of dealing with a team’s negative energy?

If you answer “no,” “maybe,” “don’t know,” “not really,” or “did it once,” you would be unwise to facilitate by yourself. Partner with someone who can answer these questions affirmatively and have him or her teach you how to handle complex situations.

Some Important Differences Between Retrospectives and Postmortems

While a retrospective and a postmortem involve the same procedures and share the same goals, there are differences between the two. A postmortem is a more in-depth, intense, and demanding undertaking than a retrospective, leaving little room for a facilitator to take a risk or make a mistake. It needs to be longer than a retrospective, which typically will range from two-and-a-half to three-and-a-half days. A postmortem, on the other hand, should span three-and-a-half to four-and-a-half days. Although I usually recommend that a retrospective be residential, I require that a postmortem be residential because there is so much more to explore, learn, heal, and plan that you need the extra time a residential setting provides.

As you prepare for a postmortem, allocate more time to review pre-work and more time to follow up either by phone or in person than you would normally devote. Even more important for a postmortem than for a retrospective, you will need to contact any people who have left the project. Interview them and, in cases in which their presence would be advantageous, invite them to be part of the postmortem.

Another difference between a retrospective and a postmortem pertains to the number of participants. In a retrospective, I feel comfortable leading about thirty people by myself. In a postmortem, I’ll partner with another facilitator whenever the team is larger than fifteen members.

Although the exercises designed for a retrospective work well in a postmortem, I add some additional exercises for a postmortem. Some are pertinent early in the postmortem to address the coping reactions mentioned above, and a few are meant to be used throughout to establish pride of wisdom where there once might have been shame from failure. In the following chapter are specific exercises you might want to include in a postmortem that you will rarely, if ever, need for a retrospective.