1. The Technology and Power of Language

Why a book on verbs, you may be asking? Not just verbs, but “power verbs.” There are a couple of reasons. First, there are already more books on language skills and specifically verbs than you can imagine, so the world does not need another one of those books. Second, it would not be much fun to write or read another boring language skills book (not that all the other books are boring). But, if they were so interesting, wouldn’t there be a movie or a music video of one of these books by now? Lastly, this isn’t a book about the old standby verbs. Everyone knows the 16 basic English language verbs: be, do, have, come, go, see, seem, give, take, keep, make, put, send, say, let, and get. We won’t spend much more time on these.

Power verbs, on the other hand, are verbs that are emotionally edgy, powerfully positioned, with a kick, punch, and pizzazz. There will be more on these gregarious verbs later.

There are hundreds of books, guidebooks, blogs, and other ways for people to learn about how to use grammar. However, we wrote this book because in our 35 years of experience in leading, managing, coaching, mentoring, and marketing, we learned one fundamental truth: It’s the power of the words selected and the way they are delivered—the rhythm—that makes the greatest difference in how people receive and react to words. We also realized that using power verbs added color, flavor, spark, rhythm, and kick to our poems, plays, and other writing. Many writers and speakers hang safely to bland verbs of being, which tend to be somewhat bland, dull, and pedantic but safe.

Let’s Take a Moment and Think about Language

“If you can’t describe what you’re doing...you don’t know what you’re doing.”

One of the peculiar characteristics of our culture is how we deal with communicating with one another. Communication is perhaps the most important human function in which we engage and we don’t do it very well and aren’t trained very well. Because we don’t trust our instincts driven by our amygdala (which some refer to as our animal brain) as much as we should, we have trouble really absorbing the nonverbal human communications adequately.

Think about all our acculturation that teaches us to deny our amygdala-driven instincts (e.g., “We’ll cross that bridge when we come to it,” “Don’t judge a book by its cover,” “Don’t jump to conclusions,” “Look before you leap,” “Act in haste, repent at your leisure,” “We should have a committee meeting to talk it over first”). In spite of the knowledge of how much communication is transferred by nonverbal cues, there is very little education and training in our schools to improve human nonverbal perception.

We know from empirical research that an overwhelming amount of human communications (as much as 97%) is conveyed by nonverbal cues. These nonverbal cues are what some people refer to as body language. Much of this body language is found in various facial expressions. Research has shown that in spite of wide cultural differences in language and cultural norms, there are eight universal facial nonverbal expressions recognized throughout the world. Dr. Paul Ekman spent years studying facial cues and discovered 190 muscles in the nose and eye region of humans; many of these muscles respond involuntary and are keys to determine whether a person is telling the truth or lying. Some of these muscle movements are so subtle that only a trained expert can detect movement. However, most people “feel” these by their amygdala, the almond-shaped portion of their brain or what some refer to as the animal or reptile brain. Long before humans developed our thinking brain—the cerebral cortex—our amygdala functioned and provided the fight-or-flight emotion. Fortunately for our species, we chose flight early on in a hostile environment where we were outgunned by bigger, faster, and fiercer predators. We were low on the food chain but had the advantage of having the amygdala, which allowed our species to survive and evolve.

For the 3% of human communication that is conveyed by language, we generally don’t listen as effectively as we could and our educational system often fails students and society with minimal communication skills (writing and speaking skills). When you consider that communication is how we express almost every desire, need, emotion, feeling, want, expectation, demand, and frustration to other humans, it is surprising and disappointing that lower forms of life do a better job of communicating.

We know that man communicated with other men for thousands of years prior to the invention of human language. Long before human verbal language, people found mates, raised families, hunted together, joined in early tribal communities, and selected leaders, but there was virtually no innovation, hardly any art or crafts, no real trade or commerce, and a very short life span. Then came language and everything changed.

This book is by no means an attempt to explain any particular theory of human development, but merely an extremely simplified explanation of how language may have developed for the purposes of positioning language as an important component of your culture.

Kevin Kelly wrote a book in 2010 entitled What Technology Wants. In this provocative book, Kelly introduced a brand-new view of technology in which he suggests that technology is not just hardwired metal and chips, but a living, natural system whose origin goes back to the big bang.

My intention is not to review the book. However, I would recommend it be read by every manager, supervisor, boss, mentor, coach, influencer, instigator, team leader, team member, entrepreneur, capitalist, investor, futurist, investor, provocateur, teacher, professor, minister, government employee, politician, or new parent.

One point of Kelly’s book to which I will refer is the point he makes with regard to the technology of language. However, to get to that point, it is necessary to cover some human history, so stay with me for a little while.

We know humans developed language about 50,000 years ago. There are theories that language developed slowly and other theories that it developed more or less spontaneously. For our discussion, it doesn’t matter how language developed—it only manners that human language developed about 50,000 years ago. Kelly traces the development of human language to the behavior of humans. By tracing the behavior of the human species, we can follow Kelly’s argument that language followed certain human behavior patterns.

At some point about 2.5 million years ago, the human brain grew larger and we began to use more refined tools than our ape line. Archaeological evidence shows the growth of human brains and simple stone tools. At this point, the first migration began out of Africa for two human species—Neanderthal to Europe and Homo erectus to Asia—sapiens remained in Africa. It is important to note all three species had the same brain size and same rough tools. Over the next 50 million years, all three species developed about the same pace (none with language skills). All three species hunted with simple tools, developed crude art, had children, lived relatively short lives, did not bury their dead, and the population of these groups remained unchanged. This was the Mesolithic Period.

Then around 50,000 years ago, something radically different changed, something radical happened, something very radically different occurred. The sapiens in Africa suddenly underwent significant genetic changes. The Sapiens became full of ideas and innovations and developed the desire to innovate, move, and explore new worlds. They spread out of Africa in what is known as the second migration and in 40,000 years had settled in every corner of the earth.

In a fraction of 1 percent of the time it took for the first migration to take place and for the first wave to settle in one spot, the Sapiens covered the world. Not only did the Sapiens have the desire to move, but they were also full of innovation. They developed fishhooks, fishnets, variable size spears and bows and arrows, sewing, and hearth stoves; they buried their dead; and they created sophisticated art and jewelry. Sapiens developed trade, pottery, and animal traps and built garbage pits. In the process of mastering all these innovative things, they overwhelmed their Neanderthal and Homo erectus brothers, leaving Sapiens the only human species on the planet.

The question we have to ask is what caused the radical change in Sapiens? How did it occur? It can be argued that there was a point mutation or a rewiring of the brain was the cause. We are not proposing a cause, only stating the fact that there was an outcome that something radically changed, that something happened, that something very different occurred 50,000 years ago, and that radical change was language occurred and radically changed mankind forever.

Taking the new technology one step further, language gave Sapiens and us autogeneration, which is the ability of the mind to question itself. It is a mirror that reveals to the mind what the mind is thinking, allowing self-awareness and self-reference, and language explains the innovations and ideas that have formed in the mind. Without language, we could not access the bank of thoughts and ideas. We could not tell stories, interpret case studies, or compare things; we could not consciously create.

We use language, verbal and nonverbal, to make sense of our world. We use it to interact, confirm, beg, act, command, inquire, network, court, teach, coach, and entertain. A few verbal and nonverbal messages can influence us, can change our minds, can cause us to do something different, or can change our position or vote. Words affect who we are. Without words, we would be isolated. Language and its nuances are uniquely human.

Language is something we learn completely by audio cues—by listening. We do this because human brains are hardwired—genetically prewired to learn language by listening as an infant. It is interesting that we are not even consciously aware we are cognitively learning. Before we had the ability to speak words, others could understand us. Our species survived and advanced, making other members understand with nonverbal cues. For millions of years, children communicated to their mothers that they were hungry. Men communicated to women and women to men that they were interested in them as partners. Hunters collaborated on big animal kills long before a word was spoken; man even showed another how to start and keep a fire going long before there were words for such things. Anthropologists believe the spoken word appeared on the scene around 50,000 BC—a long time to use grunts and pointing and body language.

The special significance of language as a great idea lies in the fact that it is related to all other great ideas insofar as ideas and thoughts are expressed to other persons, for the most part, in words, in speech, in language.

In Plato’s dialogues, he used Socrates as a character and he spoke of people continually, calling attention to the slippery nature of words and how sometimes words conceal thoughts as well as express them. In more modern times, philosophers like Hobbes and Locke wrote about the abuse of words and how language should be used.

Today, we sort of view language as an enemy, a barrier to communication, a tyranny of words. There is even a debate over whether communications and speech are the same thing.

The Power of Words

“A very good part of the mischief that vex the world arises from words.”

As Dr. Frank Luntz says, “It’s not what you say. It’s what people hear” (Luntz 2007, xi). The meaning of this is the audience will translate your message through a prism of their own biases, interests, knowledge, awareness, feelings, attention span, and many other interpretative filters.

Once you have spoken words, they are no longer yours. Other people will translate them, evaluate them, and measure them. Choose your words, make them appropriate for the situation, and be aware of the power of words. Poorly chosen words or speech used for personal, hubris, or evil can impact self-esteem, destroy morale, kill enthusiasm, inflame bias, incite hatred, lower expectations, hold people back, and even make people physically or mentally ill. Inappropriate words can make work and home toxic, abusive environments. There are many empirical studies showing that people who live and/or work in toxic environments suffer more colds, more cases of flu, more heart attacks, more depression, more of almost all chronic disorders, physical and emotional, than people who report living and/or working in happy, enjoyable, caring environments.

The old parental advice, “Sticks and stones can break your bones, but words can never hurt you,” was simply bad advice. However, well-chosen words or speech for the benefit of good or hope for others can motivate or inspire others to greater feats and deeds. They can offer hope; create vision; impact thinking beliefs and behavior of others; and alter results of strategy, plans, objectives, and people’s lives.

Peggy Noonan, the national syndicated columnist, knows a thing or two about words and how they impact us. She wrote recently about the advice Clare Boothe Luce once gave the newly inaugurated U.S. President John F. Kennedy. Ms. Luce was truly a remarkable woman. Her career spanned seven decades and nearly as many professional interests—journalism, politics, theatre, diplomacy, and intelligence.

According to Ms. Noonan, the sentence idea comes from a story Clare Boothe Luce told about a conversation she had in 1962 in the White House with her old friend John F. Kennedy. She said she told him that “a great man is one sentence.” His leadership can be so well summed up in a single sentence that you don’t have to hear his name to know who’s being talked about. “He preserved the union and freed the slaves” or “He lifted us out of a great depression and helped to win a World War.” You didn’t have to be told “Lincoln” or “FDR.”

She wondered what Kennedy’s sentence would be. She was telling him to concentrate, to know the great themes and demands of his time, and focus on them. It was good advice. History has imperatives, and sometimes they are clear. Sometimes they are met, and sometimes not. When they’re clear and met, you get quite a sentence (Wall Street Journal 2009).

Let’s look at a more contemporary example: the historic 2012 presidential debates. These debates may have more significance than previous ones because of the words chosen by the candidates, their rhythm, and their physical, nonverbal cues. A big part of communicating successfully depends on how well we negotiate the paradox of how the vast majority of human communication is conducted.

We know that more than 97% of human communication involves nonverbal cues (body language). To have a successful presentation, speech, or presidential debate performance, we must compose a sophisticated but seamless message, uniting our words in the proper rhythm, and use the corresponding nonverbal cues. If the words chosen don’t match the nonverbal cues or vice versa, the audience will be confused and the message will be diminished or, worse, ignored.

In the world of movies, theater, art, and entertainment, words have a dramatic impact. In a recent Wall Street Journal edition, a special report entitled “What’s In a Name?” discussed a number of box office successes that might have had a different result if their original titles had not been changed. For example, the Bogart classic Casablanca had an original title of Everybody Comes to Ricks. The Julia Roberts/Richard Gere blockbuster Pretty Woman had an original title of $3,000. The successful G.I. Jane was supposed to be released as In Defense of Honor. The world might not have ever remembered Diane Keaton and Woody Allen in Anhedonia, which was fortunately changed to Annie Hall (Wall Street Journal 2012).

Words have the power to affect both the physical and emotional health of people to whom we speak, for better or for worse. Words used to influence are inspiring, uplifting, and challenging. They encourage, motivate, and persuade; they can be visionary; they can change people’s lives for the better. Verbal communication is a powerful human instrument, and we must learn to use it properly. We need to not only learn to think about speaking in new ways, but also learn to think about language and human nature, psychology, and sociology.

Throughout history, there have been many examples of memorable quotes to demonstrate how what is said is just as important as how it was said. For example, when Lyndon B. Johnson was stumping for political office, he was debating an opponent and was asked the difference between himself and the opposing candidate. He famously replied, “He matriculated and I never matriculated.”

Some of the most famous speeches made by Abraham Lincoln are memorable not just for the message, but also for the fact that he condensed an enormous amount of information into them. It was not only the power of his words, but also his cadence that made the impact of the speeches more powerful. His second inaugural speech was only 700 words and the Gettysburg Address was just under three minutes.

The power of words can actually harm others. Power verbs express an action that is to be taken or that has been taken. When used correctly, a powerful verb has the power to impact your life whether you are going into battle, running for president, or simply interviewing for a job. Researchers have observed that when students are given standardized tests and told the tests are “intelligence exams,” the average scores are from 10% to 20% lower than when the same exam is given to similar students and told it is “just an exam.”

We know that words create impressions, ideas, images, concepts, and facsimiles. Therefore, the words that we hear and read influence how we think and consequently how we behave. This means there is a correlation between the words we select and use and the results that occur.

Using powerful verbal imagery helps people to imagine vivid images and allows people to figuratively and literally see concepts being mentioned. This was first discovered in the early twentieth century and was initially known as the Perky effect and later called visual simulation. Individuals can project abstract thoughts. Almost everyone does this from time to time, but we refer to it as daydreaming. When a person daydreams, he is completely awake and his eyes are wide open, yet he imagines being somewhere else, doing something else, seeing smoothly, and doing something else.

Visual simulation impacts what people hear and how fast they respond. A cognitive psychologist, Rolf Zwann, has done a lot of research on how people describe objects and shapes to which they are exposed. The experiment includes just showing people visuals, asking for responses, and providing audio prompts before the visual stimulation. The results indicated people respond faster if they are given visual and aural stimulation before being asked to see the shapes. (Bergen 2012, 95). Many studies have confirmed that people construct visual simulations of objects they hear or read about.

People construct shape and orientation simulation. Studies show that when people listened, they more often looked at the set of objects that fit with the meaning of the verb, even before they heard the name of the relevant object. People make predictions about what the rest of the sentence will contain as soon as words that they have already heard start to constrain what could reasonably follow. People start to cobble their understanding of the sentence incrementally (Bergen 2012, 125).

Grammar helps get the visual simulation going by pulling together all the pieces contributed by the words in the correct configuration. People will more easily and clearly understand and comprehend your meaning if you have structured your sentence correctly.

One particular form is transitive sentences. It is one that has a transfer of possession meaning. They start with a noun or noun phrases, are followed by a verb, and then have one or two noun phrases. The following is an example:

The outgoing CEO kicked the problem down the road to the new CEO.

If we use the intended transfer definition, the ditransitive describes an intended transfer of an object to a recipient, and, naturally, the recipient must be capable of receiving something (Bergen 2012, 106).

Words we use and the impact they have can even be impacted by our background and other influences. Consider the words buy and invest. If you are selling life insurance, you want the customer to buy, but in your mind, the purchase is a long-term investment. The premiums will be invested, the face value of the policy will grow, there will eventually be loan value, and the investment will appreciate beyond the purchase price.

However, the customer thinks in terms of buying and how much it costs. The issue comes full circle again if the customer does buy and if he or she wants the insurance company to make good investments.

Nan Russell writing for Career Know-How introduces this word choice: problem or challenge. Would you rather your boss see your mistake as a problem or a challenge? Is it just semantics? Problems are things that are fixed; challenges are met. Different words evoke a set of different emotions and different feelings. People usually have a much more positive feeling about “meeting a challenge” than “fixing a problem.”

There is information about the medicinal benefits of power verbs as well as a warning about the power of words which, if used inappropriately, can actually cause individuals to become ill.

“In the study, published in Pain, researchers used functional magnetic resonance tomography (fMRI) to examine how 16 healthy people processed words associated with experiencing pain. The brain scans revealed which parts of the brain were activated in response to hearing the words.

In the first experiment, researchers asked the participants to imagine situations that corresponded with words associated with pain—such as ‘excruciating,’ ‘paralyzing,’ and ‘grueling’—as well as negative but non-pain associated words such as ‘dirty’ and ‘disgusting’ and neutral and positive words. In the second experiment, the participants read the same words but were distracted by a brainteaser.

The results showed that in both cases there was a clear response in the brain’s pain-processing centers with the words associated with pain, but there was no such activity pattern in response to the other words. Researchers say preserving painful experiences as memories in the brain may have been an evolutionary response to allow humans to avoid painful situations that might be dangerous.” (http://www.webmd.com/pain-management/news/20100402/words-really-do-hurt)

Using Words in Special Ways

Words are used to paint pictures. Public speakers, teachers, radio broadcasters, and others who have an audience listening to a voice as their primary medium for communication paint pictures with words.

Weave in Beautiful Words

What words make you feel warm and happy? Sure, it’s different for all of us, but there are some words with universal appeal (at least in English). The British Council, which oversees education of the English language, conducted a study of the “Most Beautiful Words in the English Language.”

40,000 people participated in the study. The top ten words were the following:

1. Mother

2. Passion

3. Smile

4. Love

5. Eternity

6. Fantastic

7. Destiny

9. Liberty

10. Tranquility

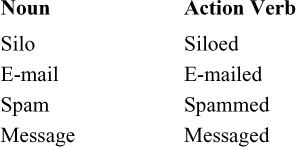

In our culture, there appears to be a growing trend of taking words that are nouns and converting them into verbs. Verbed (a word that has been used by many in the social media blogosphere to signify that so many nouns have become verbs in our everyday language) has made its way into the mainstream and is used in everyday language.

Some used more frequently are in regard to social media. The social networking site Facebook, which includes users from President Obama to our own mother and grandmother, has also become a verb itself used to describe the action of communication. Facebooking someone now means to send a message or post to his or her wall. The process works in reverse as well. The term for this is nominalization; when you turn a verb (or an adjective) into a noun, you nominalize it, creating a nominalization.

Examples include the following:

Some verbs do not change their form when nominalized, such as the following:

Another example of converting a noun into a verb is the search engine Google. Don’t know the answer to something? Then Google it. The same can be said for texts. The action of sending a text has become shortened and used as the verb texting.

Power verbs are vigorous, direct words and should be active not passive. An example of a passive approach would be, “The employee survey was conducted with a small sample.” A much better active approach would be, “We conducted the employee survey with a small sample.” The speaker should use the passive voice when it is important to focus on the object of or recipient of the action rather than on the actor.

Power verbs used in this book denote some sort of action. Our concept of action includes, but is not limited to, movement, feelings, cognition, attention, creation, transfer of something, or change of condition. However, there will be verbs that aren’t really full of action, per se, such as resemble, relate, and so on. So, one more exception to the many rules of English: Not all of our power verbs will express direct action.

Power verbs are a way to express a critical action or condition not as a noun, but as a verb.

For example, this sentence:

“The office manager made a decision in favor of an early closing due to the weather.”

could be replaced by a better construction:

“The office manager decided to close the office early due to the weather.”

Another example:

The sentence:

“Sufficient tests were conducted on the new hardware by the IT staff.”

could be replaced by a better construction:

“The IT staff tested the hardware sufficiently.”

In these examples, the power verbs gave the sentence more pop and more emphasis and the sentence was shortened, making it easier to read and understand.

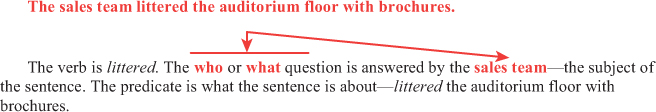

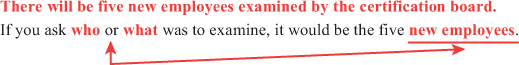

We know we told you no grammar, but we have to support the purpose of the power verb. Verbs are the most important part of a sentence or phrase. They assert something about the subject and express action, event, or state of being. The verb is the critical element of what the sentence is about (predicate).

To determine the subject of a sentence, first identify and isolate the verb and then ask a question by placing who or what before it and your answer is the subject.

Note: Be careful of sentences that begin with there plus any form of the verb to be. In these cases, there is not the subject—it merely signals that the true subject will follow.

Sentences that give a command or an order differ from conventional sentences in that their subject, which is always you, is understood rather than expressed.

Sit for the exam. (You is understood before sit.)

The English language has three main types of verbs (there are more, but remember, this isn’t a grammar book):

1. Transitive

A transitive verb is a power verb that takes on one or more direct objects, which is another way of saying the power verb is followed by a noun or a noun phrase. The meaning of the power verb (transitive verb) is incomplete without the direct object(s). To determine whether a power verb is transitive, simply ask if the action is done to someone or something.

Does the subject act upon someone or something? If it does, the power verb is transitive, and the person or thing that receives the action is the direct object.

Of course, there is a grammatical term direct objects. Why? Because they refer to the object being acted upon.

Examples:

A way to identify the transitive verb is to invert the sentence, making it passive:

(a) The plan was read by my associate.

(b) The national sales contest was won by our sales team.

The meaning of a transitive verb is incomplete without a direct object.

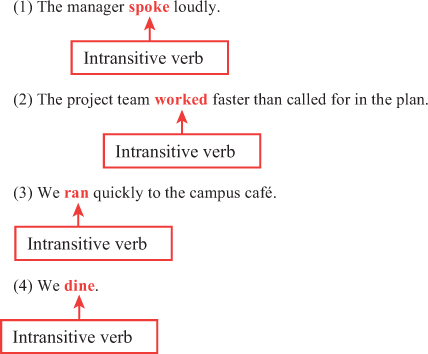

2. Intransitive

An intransitive verb is a power verb that does not have a direct object—power verbs that are not directly followed by a noun or adjective. Most of the time, intransitive verbs are followed by an adverb—a word that addresses how, where, when, what, and how often. The action ends or is modified by an adverb or adverb phrase rather than being transferred to someone or something else. Typically, an adverb or verb ends the sentence.

To determine whether the power verb is intransitive, ask whether the action is done in some way, in some direction, or in some degree. Does a noun or power verb receive the action? The power verb does not pass on its act to anyone or anything in the sentence. Such intransitive verbs generally dissipate action in themselves.

Examples:

3. Linking

Linking verbs are power verbs that do not show action; instead, the linking verb renames or describes the subject. Linking verbs do not act on an object but simply make English sentences flow correctly and smoothly. Their primary function is to connect the subject of the sentence to a complement, the part of the sentence following the verb, which is the word or group of words that complete the predicate.

Power verbs cannot be followed by an adverb or end a sentence but instead must be followed by a noun or an adjective, whether in a single word or phrase.

Current linking verbs indicate a state of the subject, such as appear, be, became, feel, look, remain, seem, smell, sound, stay, and taste.

Examples:

(1) The chairman of the board looked worried.

(2) Tom remained a reliable employee.

Resulting linking verbs indicate that the verb complement’s role is a result of the process described in the verb, such as become, get, grow, fall, prove, and run.

The Impact of Power Verbs

People, especially the millennial generation (those born after 1977), don’t talk much on the phone anymore; they text each other. Although texting is fine for quick, impersonal communications, it should never be substituted for professional communication. This phenomenon of taking nouns and turning them into verbs means that the English language is constantly evolving and changing, and therefore style manuals are outdated before they even hit the shelves, which is why this book is not a style manual.

This book does not attempt to identify these urbane, hip, or chic fad words. Instead, a number of nouns that are now action verbs have been included in this compilation because in today’s business culture, the commonly accepted practice is to include particular noun/verbs in the vernacular. Examples of these nouns that have also become accepted action verbs include the following:

The impact of action verbs and how they are woven into our collective conscience is evident in the names that advertisers use for their products. For everyday items, we associate those products with action verbs. For example, the Accord car model, Act mouthwash, Agree shampoo, Allure ski product, Ban deodorant, Budget Rent A Car, Converse sneakers, Dodge cars, Eclipse exercise machine, Endeavor spaceship, Edge shaving cream, Equal sugar substitute, Escalade Cadillac, Excel software, Glamour magazine, Gleem (gleam) toothpaste, Google the company, Intuit software, Kindle e-reader, Marvel comics, Pilot pens, Pledge cleaner, Pioneer sound systems, Puff tissues, Quip the precursor to the fax machine, Raid bug killer, Shuffle iPod product, spam, Target retail store, and Vanish home-cleaning product. There are many more...these are just a few examples.

Over the course of time, the inconsistency of English grammar has made it increasingly difficult for nonnative speakers to learn English and even difficult for those who speak English as a first language to speak correctly. Some rules and styles are antiquated and not enforced. As a result, we have become lazy and are losing the war on poor grammar. English is a minefield of rules, and while I can assure you that this book is not a style manual, it goes without saying that if you were to follow all of the rules, then you would have to spend a lifetime studying them, you would end up speaking a language that a normal person would not understand, and, finally, you would be a complete bore.

As with any rule, there are also exceptions, counterexceptions, special rules, do’s and don’ts, and other confusing rules. There are over 60 different rules and variations of rules for verbs alone. Once you have learned the rules, you still have to follow exceptions. For example, consider the word lightning used as a verb. We say it is “thundering and lightning all night.” In this case, it is the only exception to the rule that ing can be added to the base verb to produce the -ing form. We do not say or write it as “thundering and lightninging all night,” nor do we say or write it as “thundered and lightning all night”; in another exception to the rules, we say “we relayed a message” but “we relaid a carpet” (Crystal 1995, 205).

For all my former English teachers, professors, and the dedicated writers of the grammar books on linguistic style and theory who will wonder why there is nothing in this book about active and passive voice, conjugation, copulas, indicative, imperative, subjunctive mood, gradability and comparison, person and number usage, verbal dueling, lexical, linking verbs, modal, primary, axillary, serial, deflective, and transitive or intransitive usage, that is your job. This guide can be thought of as a road map to help individuals toward success in everyday communications. It is that simple!

There is no attempt to excuse people from their responsibility and duty to learn the language correctly. However, there is a time and place for everything. Noam Chomsky, perhaps the most influential figure in the theoretical linguistics of the English language in recent times, conceived the goal of linguistics (all the rules, principles, and regulations) as a description of the mental grammar of native speakers.

Chomsky perceives linguistics to be the system of all these rules to those that characterize the mental structure that underlies our ability to speak and understand the language. Furthermore, Chomsky hypothesizes that humans have an innate language ability that enables children to acquire a mental grammar quickly when they are exposed to a particular language.

It’s pretty amazing to think that a child learns an entire language by listening and some nonverbal cues. By the age of five, a person has about 70% of their lifetime vocabulary and linguistic rules learned by listening and observation.

Chomsky (and this is the last reference to a theorist or an intellectual, I promise) draws a distinction between competence in a language and performance in a language. Competence is the underlying knowledge of the theory and applications, whereas performance is the actual use made of that knowledge. This book doesn’t assume anything; it provides a performance tool for one part of the language—POWER VERBS.