2

Inside the Minds of Those You Are Changing

Those who manipulate obsess on persuasive tactics they can follow.

Those who influence obsess on understanding the decision process followed by those they are persuading.

For over twenty-five years I have polled audiences regarding the unique decisions they make, and through various economic crises, a couple of wars, and a handful of other historic moments, I’ve learned one important thing: People go through repeatable, predictable steps when they make changes, regardless of the specifics of the decision in question. Understanding how people make decisions is critical when learning how to change minds and influence another’s behavior. As with many great ideas, discovering this process was almost an accident.

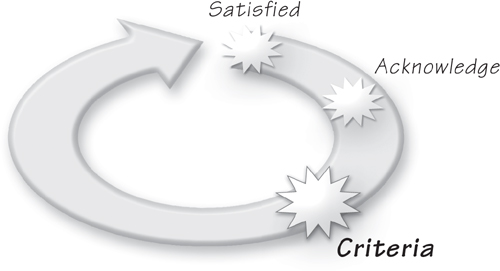

THE DECISION CYCLE

I have learned many different sales tactics over the years. When I worked at New York Life, I learned the Live, Die, Quit story, the Hundred Man story, and a few other impressive scripts. When I worked at Xerox, I learned SPIN: Selling, Strategic Selling, and a few other impressive processes. We were tasked with training the salespeople at the Xerox authorized dealerships who were selling our products. It would have been easy simply to teach them the same process the Xerox sales force was using. One small problem: The selling process we used was licensed to be taught only to Xerox personnel. Dealerships may have been authorized to sell Xerox products, but they were not Xerox personnel.

Unfortunately, Xerox did not own a sales process of its own at that time. They had owned a program of their own (Professional Selling Skills), but sold it off for a tidy profit. So, in 1986, with no existing sales process of our own, we set about to create a program that would truly belong to us. We wanted our program to be as progressive as possible, and we wanted to include every persuasive tactic we could imagine. When the smoke cleared, we had a repeatable and predictable process we could use to teach selling. But this exercise revealed a new question: What about the customer? Is there a repeatable, predictable process that customers go through when making a decision for change?

Once we began looking at the ways customers make decisions, we began to see definable stages and decision points. In addition to being fascinating, it forever changed the way I viewed the art of influence. Initially, it was referred to as a buying cycle. But the more companies I worked with, the more I knew we had to find a new name for a process that was more universal. With clients such as police departments, NASA engineers, teachers, lawyers, doctors, and others, I was working with people who did not think of themselves as selling anything. They did realize, however, that they were working with people who were struggling to make certain decisions. They were working with individuals who were demonstrating a true decision cycle.

The longer I have studied this side of the equation, the clearer the benefits have become. To this day, one of my favorite questions for an audience is this: Do you believe that people go through repeatable, predictable processes when they are making a decision? Interestingly enough, the audience’s reaction is usually mixed. I follow up with this question: “Suspend your disbelief for a moment, and suppose I can prove to you this process does exist. If you’re trying to help people make a change they are struggling with, wouldn’t it be useful to understand the decision process they are going through, and where they are within that process?” I usually see some heads nodding at this point. This knowledge is more than an effective guide to working with others; it helps you find the appropriate tactics to assist others who are struggling with decisions.

The rest is history. The proof comes from the more than 50,000 people I have personally polled over the past twenty-five years regarding the decisions they have made. Knowing this not only helps you to see things from another person’s perspective, it provides a window inside the minds you are changing.

I can’t emphasize enough how important focusing from another person’s perspective can be when changing minds. You don’t believe a process like this exists? Let’s see if we can prove it by relating it to your own life. Consider the six stages I will now outline, and see if they resemble the process you followed as you made a recent important decision in your own life. While you track your example, I’ll track an example of my own.

THE SATISFIED STAGE

Even in a repeatable cycle, there has to be a beginning, and the satisfied stage represents just that. In this stage of the cycle, individuals are convinced they have no needs, and no problems. In their minds, everything is perfect.

I’m all for more people in this world being happy and feeling everything’s perfect; I just don’t believe most people are telling the truth. Before you get upset about that, consider this question: What percentage of people are truly in the satisfied stage regarding events within their lives? 50 percent? 40 percent? 30 percent?

Allow me to separate facts from feelings. The real answer is somewhere between 4½ and 5 percent. Surprised? Those are numbers I can support with decades of research. What I can’t support is my feeling that this number is actually closer to 2 percent. I believe that fully half of those who say they are 100 percent happy with a given scenario are not lying; they are simply unaware.

How many times have we heard on the news that a particular product we thought was good for us was not good for us after all? Just because we are unaware of a problem doesn’t mean the problem doesn’t exist.

Our First House

Can you remember the first house you bought? I can sure remember mine. I was newly married, and my wife and I decided it was time to move from our condominium. It was a seller’s market, and real estate was moving fast. It wasn’t unusual to see a house go on the market, and within twenty-four hours have three or four contracts written at or above the asking price. We had lost one house we liked a lot because we were slow to put down a contract, so when we got word of a house that was going on the market in the morning, we came rushing in the night before. We wanted to be ready to move fast, and we did.

We saw a beautiful Cape Cod home in Bethesda, Maryland, which we fell in love with. The location was almost perfect. A few blocks inside the Capitol Beltway made it close to everything. We especially loved the quiet little cul-de-sac it was located on … on that particular day. It was our house, on a quiet little cul-de-sac, and we loved it!

![]()

There may very well be issues to deal with in the future, but the satisfied stage represents a kind of honeymoon that decision makers reside in for a short period of time. Honeymoons don’t last forever, and before too long we become aware that the decision we have made may not be perfect. That’s when we make our first move within the cycle.

THE ACKNOWLEDGE STAGE

And then the potential for change emerges. The acknowledge stage represents the most significant step relating to the way people make decisions, and it is the most critical element of the decision cycle. It is also the most misunderstood component.

Small Trouble in Paradise

As we rushed to put a contract down on this house, we didn’t realize that we had viewed it at the height of rush hour. The Capitol Beltway was at a standstill. What we quickly realized once our contract was accepted was that this house wasn’t just near the Beltway, it sounded like it was in the Beltway! But this was our house, on a sometimes quiet little cul-de-sac, and we loved it.

![]()

The acknowledge stage represents a basic dichotomy in our mind. In this stage, we will readily admit that yes, we do have particular problems that could require change. Unfortunately, we will just as readily state no, we do not want to do anything about these problems at this time.

Many people with whom I work tell me that this is the place in the decision cycle where most of the people they are looking to influence seem to reside. According to my numbers, they happen to be absolutely right. Seventy-nine percent of the people I survey state that this is exactly where they are in the decision cycle “It hurts,” they say, “but it doesn’t hurt very much.” There is no sense of urgency and, therefore, no serious interest in change.

I sometimes refer to this stage as the whining stage. Many of us whine incessantly but don’t do anything to alter what we are whining about. Adding insult to injury, the vast majority of the population is not only locked into the acknowledge stage, but they are locked into it for a long time.

Bigger Trouble in Paradise

As the years went by, we were thrilled by the birth of our first child, and then our second. We were also thrilled by the techniques used to neutralize the noise from the Beltway. To combat the constant noise we kept our storm windows closed year-round, installed on our deck one of the first outside speakers Bose ever made, and even purchased a device I called our “sound-a-lizer.” This was a particularly loud air cleaner we would turn on each night in our bedroom. We liked it so much, we even bought a second one because this was our house on a not-so-quiet little cul-de-sac, and we put up with the problems.

![]()

People don’t fix small problems; they fix big ones.

Two things keep people paralyzed in the acknowledge stage. The first is the perceived size of the problem. Regardless of the problem, if people do not perceive the problem as a big one, they will feel no urgency to do anything about it. People procrastinate and put off acting on the difficulties they face. That’s human nature, and that’s what keeps us all pinned down in the acknowledge stage for long periods of time. As the problem grows in size, we begin to gravitate closer to a critical decision point. When the problem becomes too enormous, we cross over a kind of metaphorical line in the sand. This line represents a decision to make a change.

The second reason people remain in the acknowledge stage for so long is an issue that will come up a few more times in this book; the fear of change. Ultimately, this fear is often the one stumbling block that challenges even persuasive people. It may not seem fair, and it may not seem right, but this fear hides inside us all.

The fear of change often outweighs the pain of the present.

Seventy-nine percent of the people I surveyed represents a lot of opportunities, from a change perspective, and I can assure you, we will influence them! For now, however, let’s stick with our scenario of what happens when there is no one to help change minds and influence behavior. In this scenario, we are left on our own, continuing to struggle, paralyzed in this stage, waiting and waiting for something to happen.

The Line in the Sand

Some years ago my wife and I owned a Mercury Marquis that was one interesting piece of work. It was a fine car, but we had it for quite some time, and over the years it developed some rather interesting—shall we say—habits. It had a rattle of some sort in the back wheel, but we got used to it. The dashboard light had a mind of its own and would turn on and off on its own schedule, but we got used to it. It had a ding here, and some rust there, and the mileage wasn’t quite what we had hoped, but we got used to all of it. In fact there were a lot of nagging issues with the Gray Ghost, as we called that car, and we mumbled from time to time that we should probably get rid of it, but that was just idle chatter.

Then one day the Gray Ghost surprised us with a new interesting habit. As we were driving to a friend’s house in a quiet little suburban neighborhood in Maryland, early in the morning, the horn started honking all by itself. As soon as we completed our turn into the neighborhood the horn stopped. Mortified, we continued on. A couple of blocks later we turned again, and again the horn, apparently with a mind of its own, went off. Quickly, we completed the turn and it stopped again. As luck would have it, we had to make at least four more turns, and each time we took a turn, that horn announced our arrival to everyone on the street.

When we finally reached our friend’s house and turned off the car, we were clear on two things. First, we needed to cut the wire to that car horn. Second, we needed to say good-bye to the Gray Ghost. We had crossed that line in the sand from not liking something, to deciding to do something about it. We had made a commitment to change.

![]()

When it comes to making decisions, it’s clear that we go through repeatable, predictable stages. However, within this cycle there is one significant moment of truth that seems to be missed by many, and yet is vital to those who seek to change minds. I call it the line in the sand.

I am not a cynic, but I am a realist. These two things I know to be true:

![]() It is human nature to spend months, if not years, living with problems we are capable of fixing but don’t. We wait until little problems become big problems, and change often comes too late.

It is human nature to spend months, if not years, living with problems we are capable of fixing but don’t. We wait until little problems become big problems, and change often comes too late.

![]() It is human nature to fear change, and that fear can be so blinding that we can’t see the size and scope of problems until there is a difficult, if not devastating, occurrence.

It is human nature to fear change, and that fear can be so blinding that we can’t see the size and scope of problems until there is a difficult, if not devastating, occurrence.

We live with these problems, we justify these problems, we whine about these problems, we sulk about these problems, we turn away, and we even deny these problems exist. And then something happens.

That something can be as simple as a comment that catches us by surprise, or as disastrous as being fired from a job. But something happens. When that something happens we cross a line I’ve nicknamed the fix, don’t fix line and it is a mythical line in the sand. When we cross the line, we don’t commit to a solution; we commit to a change.

![]() We can complain about an unfulfilling job for years. We’ve crossed that line in the sand when we redo our resume and begin networking.

We can complain about an unfulfilling job for years. We’ve crossed that line in the sand when we redo our resume and begin networking.

![]() We can complain about an unfulfilling relationship for years. We’ve crossed that line in the sand when we find ourselves a therapist and set an appointment.

We can complain about an unfulfilling relationship for years. We’ve crossed that line in the sand when we find ourselves a therapist and set an appointment.

![]() We can complain about a car that has too many miles on it. We’ve crossed that line in the sand when we find ourselves pulling into a dealership.

We can complain about a car that has too many miles on it. We’ve crossed that line in the sand when we find ourselves pulling into a dealership.

There are moments of truth in all our lives, which frequently initiate change. Personally, I’d rather help someone avoid a catastrophe than clean one up, and that’s why this line in the sand is so important to me. Understanding this line reminds me how important it is to help others navigate this line. It’s not unusual to struggle with change; we all do. What is unusual is for people, on their own, to fix these problems before it’s too late.

THE CRITERIA STAGE

And then something does happen. Sometimes it can be a traumatic situation, and other times it can be the combination of a lot of smaller issues. However, one way or another, we make our decision for change and begin to look for alternatives.

The Straw that Broke the Camel’s Back

One day, on a beautiful summer evening, we threw a party. Storm windows were down, speakers were on, and sound-a-lizers were sound-a-lizing. Later in the evening, when we heard, “What’s that roaring sound?” from a party guest for the third time, my wife and I looked at each other and made a decision. We didn’t put our house on the market in the morning, nor did we contact a realtor … yet; however, we had crossed a critical decision point. We were committed to making a change. This was our house, but it was on a cul-de-sac that was just too loud with traffic noise, and we were fed up with it.

![]()

It could be a bad kayaking trip that left a smoker out of breath and fatigued, or it could just as easily be seeing someone else’s misfortune. Once the problem grows in size, we look for alternatives. Sadly, often this newfound realization comes too late.

When I sold insurance for New York Life, one thing the managers hated to see was agents sitting by the phone, waiting for it to ring. People do not sit down and call their agents unless something is wrong, usually very wrong. On the rare occasions when I did receive a call from a customer looking for insurance, our conversation would literally go like this:

“Hi, I’m looking for insurance.”

“That’s wonderful. What did the doctor tell you?”

“Pardon?”

“Well, when you went to the doctor today, what did he tell you?”

“Uh, well … he said my blood pressure was going up.”

Our problems dominate the size and shape of our needs.

I wasn’t a genius or a palm reader. I just understood human nature. In this stage of our decision making, we have often gone through an emotional crisis of some sort and are looking to fix whatever is bothering us. The single most critical lesson to learn within the process lies right here. It is proved over and over again, day after day, that our problems clearly shape our needs. Consider some of the decisions you’ve made in the past.

![]() That house you bought a few years ago just had to have a fenced-in yard. I’m wondering how many times your dog got loose from your previous, un-fenced yard.

That house you bought a few years ago just had to have a fenced-in yard. I’m wondering how many times your dog got loose from your previous, un-fenced yard.

![]() That job you took a few years ago just had to be within ten miles of your home. I’m wondering how many hours you spent snarled in traffic during the difficult commute you used to have.

That job you took a few years ago just had to be within ten miles of your home. I’m wondering how many hours you spent snarled in traffic during the difficult commute you used to have.

![]() That car you bought a few years ago just had to have Bluetooth installed. I’m wondering how close you were to rear-ending the car in front of you while trying to dial a number on your cell phone.

That car you bought a few years ago just had to have Bluetooth installed. I’m wondering how close you were to rear-ending the car in front of you while trying to dial a number on your cell phone.

![]() That employee you hired a few years ago just had to have a track record of loyalty and cooperation. I’m wondering how undependable the employee you replaced was, and how damaging his or her lack of loyalty was.

That employee you hired a few years ago just had to have a track record of loyalty and cooperation. I’m wondering how undependable the employee you replaced was, and how damaging his or her lack of loyalty was.

The Problem Shapes the Need

No, we didn’t go looking for a realtor the day after that infamous party; we waited about a week. The market had changed to a buyer’s market, which meant we had a lot of houses to choose from. Big ones, small ones, simple ones, fancy ones, and yet, we were fixated on only one criterion: a quiet location. This fixation led us to the quietest location in the Washington metropolitan area—Great Falls, Virginia. With most of the city still bound by two-acre zoning laws, and only one two-lane road that ran through it, we had found our quiet town. This was by no means a coincidence. This was going to be our new house, perhaps on a cul-de-sac, but without traffic noise, and we were excited about it.

![]()

No, needs don’t just pop up out of nowhere, nor does our motivation to seek change. Now, with a better understanding of not just what we need but also of how our problems become needs, we move to the next stage.

THE INVESTIGATE STAGE

We now look for a solution. Equipped with a list of criteria, the search for a resolution begins. The investigate stage may involve the act of actually looking for the same product at different locations. For example, if you were choosing a car, you may decide to buy a Ford Taurus. Then the second half of your decision would be where to buy it. Chances are you might visit a couple of dealerships in search of your dream Ford.

The Search for Silence

We were so fixated on the quiet location of this house, we actually put each house we viewed through the, “sound test.” We never visited a home during rush hour, and when we drove up to it, we would roll down all the windows and shut off our car engine, and if we heard anything that sounded remotely like another car, we did not even enter the house. Any noise was a deal breaker. After all, this was going to be our new house, perhaps on a cul-de-sac, but one without traffic noise, and we would not compromise.

![]()

Some of the individuals whose decisions I have tracked and studied have proudly told me, “I went with the first car or house I saw.” I believe this assertion but I question its logic. Having learned my own lessons, this is not something I would brag about. Often, even if the first selection turns out to be the best selection, the more thorough we are in the investigate stage, the less buyer’s remorse we are likely to experience down the road.

With the comparing and shopping out of the way, we have finished our homework. At last, we are nearly ready to make the final decision.

THE SELECT STAGE

And all that is left to do now is make your move. Perhaps as a result of the slow, sometimes painful, process to get here, it is not unusual to feel a sense of euphoria when you say yes and act on the urge to change. When you actually study how people make choices, you observe that their final decision is often the easiest one. They often feel a release of tension when they make their ultimate decision.

Pulling the Trigger

After a few months of careful searching, we took the plunge and bought our new house. We finally found a home, on a meticulously noise-tested cul-de-sac, and we loved it!

![]()

There really is not that much more that can be said about the select stage. It might just represent the most basic, quickest step within the cycle. Unfortunately, you better not blink, because chances are you will not stay here for long. Often, within months, we move on.

THE RECONSIDER STAGE

Now we head toward the reconsider stage. Sometimes referred to as buyer’s remorse, this stage is inevitable. It’s really not a question of if we go through this stage; it’s more a question of when.

The severity of the reconsider stage is often in direct proportion to the size of the commitment of the solution. After a brief touch of remorse, we move on through the cycle, landing in the satisfied stage, and the process begins to repeat itself once again.

Buyer’s Remorse

Buying a house is a big deal, and I’m not going to tell you I didn’t have a second thought or two the first time I heard a slight groan from the plumbing, but it was our house, on a meticulously noise-tested cul-de-sac, and we loved it!

![]()

With a few variations, this repeatable and predictable process is the same from decision to decision, scenario to scenario, and industry to industry. Therefore, success is not solely determined by your ability to apply a series of tactics used to change minds and influence behavior. In fact, success lies in your ability to understand where someone is in his or her decision cycle and to line up the appropriate tactics necessary to influence change. Of course, this is a fluid process and it is important to remember that the process doesn’t end here.

The Process Continues

It’s been twenty-two years since we moved into our home in Great Falls, Virginia. We raised three wonderful children in this quiet home, on a cul-de-sac, and we have loved it. We’re approaching our next phase in life as empty nesters, and that means another move. We got our quiet home in a fairly rural location. Of course, to have a quiet location, you have to sacrifice other things. A fairly rural location means limited mass transit opportunities, and a lot of driving for even the most basic needs. It also means frequent loss of power from downed trees during even a moderate storm. So, our next house may very well be in the city, where we can use mass transit, and wake up and walk for a cup of coffee. There’s a very good chance our house will have a generator as well. I’m sure it will be a beautiful house, perhaps on a cul-de-sac, and I’m quite sure we’ll love it.…

![]()

Over the past twenty years I have continued to poll my audiences in a participant pool that now numbers well over 100,000. Through good times, and bad, strong economies and weak, tangible and intangible solutions, the numbers have not varied by more than two percentage points. Three statistics should jump off this chart:

Credit: Jolles Associates, Inc.

1. 79 percent of those polled, when not pressured to consider a solution—that’s almost eight out of ten—will admit to an awareness of a problem. Unfortunately, these same people will also admit to not wanting to fix the problem … yet.

2. 10 percent of those polled are considering alternatives to their current problem and are receptive to a solution if one is offered.

3. 5 percent of those polled are in fact completely satisfied with their current situation. (If you are struggling with that number, and feel it’s just too low for you to believe, I ask you to suspend your disbelief for a chapter and I’ll be happy to tell you exactly why so many people deny having problems.)

It’s referred to as the decision cycle for a reason. The cycle is fluid and continuous. Understanding this cycle of change provides a key building block when learning how to change minds, because understanding this part of the process provides logic to the moves we must learn to make when influencing behavior. It also reminds me of an important question you will find repeated in the text that follows, the first question we must ask ourselves before we make even one strategic move, “Where is this person within his or her decision cycle?”