Foreword

This handbook represents a significant advance for decision professionals. Written for practitioners by practitioners who respect the theoretical foundations of decision analysis, it provides a useful map of the tools and capabilities of effective practitioners. I anticipate that this and future editions will become the primary repository of the body of knowledge for practicing decision professionals.

This Handbook Is Timely

The practice of decision analysis (DA) is at a major inflection point. That high-quality decisions can generate immense value is being demonstrated again and again. Leaders of organizations are increasingly aware of how opportunities are lost by making “satisficing” decisions—that is, decisions that are “good enough.” The benefit-to-cost ratio of investing in better decisions is frequently a thousand to one. I know of no better opportunity for value creation anywhere. As Frank Koch,1 president of the Society of Decision Professionals (SDP), has said, “Benefit to cost ratios … are immense simply because the added cost of doing DA is negligible. We would still be paying the analysts and decision makers without DA; they would simply be talking about different things. The incremental cost of having a better, more relevant conversation is zero, so regardless of the benefit, the ratio is infinite! Even if I throw in the cost of training and learning some software, that’s measured in thousands and the benefits are clearly measured in millions.”

Why is this huge opportunity still a secret from most decision makers? It is because we humans are wired to believe that we are making good decisions even when we leave value on the table. We are wired to be satisfied with good enough. We shape our memories with hindsight and rationalization. The burgeoning set of literature from the behavioral decision sciences documents many of our biases and draws attention to the gap between true decision quality (DQ) (see Chapter 5) and our natural decision-making tendencies.

Our individual cognitive biases are amplified by social behavior, like groupthink. We assume that advocacy decision processes in use by most organizations produce good decisions, yet they are designed to suppress good alternatives. We assume that agreement is the same as DQ, yet we see a lot of agreement around nonsense. It is not uncommon to hear statements like, “I can’t believe it—what were we thinking?”

If DQ can create immense additional value in specific decisions, can we develop DQ as an organizational competence? The answer is yes, and Chevron has shown the way. Over the period in which it has implemented a deep and broad adoption of DQ, Chevron has outperformed its peer group of major oil companies in creating shareholder value. While many organizations have pockets of organizational decision quality (ODQ), to my knowledge, Chevron has the broadest and deepest adoption to date. And by “adoption,” I don’t just mean better analytics. All the major oil companies have the analytics to deal address uncertainties and risk. The difference is that the whole Chevron organization seems to be in passionate and collaborative pursuit of value creation based on quality decisions linked with effective execution. I believe that Chevron’s success is the beginning of a big wave of broad adoption of organizational DQ.2

The immense value left behind by our satisficing behaviors represents the biggest opportunity for our business and societal institutions in the coming decades. If we begin to think of these opportunity losses as an available resource, we will want to mine this immense value potential. The courts—led by the Delaware Supreme Court—are raising the bar in their interpretation of a board director’s duty of “good faith.” In the coming years, board and top management’s best defense is their documented practice of DQ.

Decision Professionals: The Practitioner Perspective

The Society of Decision Professionals3 states that the mission of decision professionals is to:

- Bring DQ to important and complex decisions.

- Provide quality insights and direction through use of practical tools and robust methodologies.

- Promote high professional standards and integrity in all work done by decision professionals.

- Advance the profession to the benefit of mankind through helping decision makers.

The role of a decision professional as a practitioner of DA and facilitator of organizational alignment is gaining acceptance. Dozens of organizations have established internal groups of professionals, designed career ladders, and developed specific competency requirements. The recently formed SDP has created a certification process and career ladder that specifies increasing competency levels for practitioners.

While there are important similarities between becoming a successful practitioner and becoming a tenured academic, there are also major differences. The decision professional is motivated by bringing clarity to complex decision situations and creating value potential in support of decision makers. He or she is less interested in the specialization required for peer-reviewed publication. Instead, the practitioner wants to acquire practical tools and relevant skills that include both analytical and facilitation skills (project management, conflict resolution, and other so-called “soft skills”).

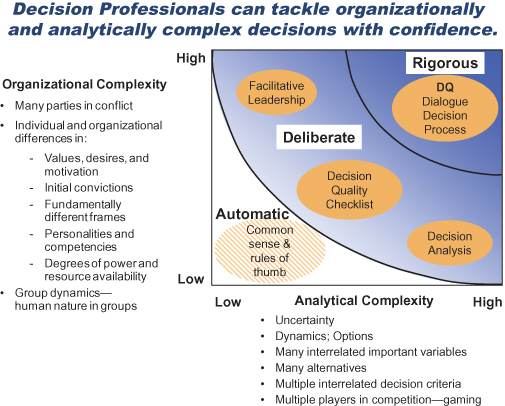

The ability to address both organizational and analytical complexity (see Figure F.1) are of great importance to the practitioner. As I like to say, “If you can only deal with the analytical complexity, you can get the right answer—but nobody cares. If you can only facilitate in the face of organizational complexity, you can resolve conflicts and gain agreement—but it can be agreement around nonsense.” To bring full value, we need to deliver the combination—agreement around the best answer, the answer that generates the greatest value potential.

Figure F.1 Two dimensions of competence.

Individual decision professionals can deliver this if we have the competency in both areas. However, many practitioners are significantly better in one or the other—either strong analytical capabilities or strong social/emotional intelligence and facilitation skills. Therefore, many practitioners find it best to team up with others to deliver the full value of DQ. To make such teaming effective, there must be mutual respect for the other competency and a recognition that value creation from the combination is the goal. It bears repeating: We need to gain alignment around the best answer—the answer that creates the greatest value potential.

As practitioners we are always approximating and simplifying. We are practical decision engineers and decision facilitators who want robust solutions that are effective in creating a lot of potential value. We are organizational facilitators who are not satisfied unless the best decision is owned by the decision makers and implementers. Incisiveness with tools that produce insight and processes that foster effective engagement are more important to us than another refinement to the axioms of normative decision theory. In my experience, the academic debates at the edges of decision science over the last two decades have contributed surprisingly little to the practice. Seldom is the primary challenge in solving real decision problems a matter of advanced theory.

Our goal should be to make our concepts and methods as simple and accessible as possible. As I am writing this, I am participating in a 2-week program to teach incoming high school freshmen the basics of decision quality and help them apply the concepts to significant school decision projects. I recommend that all decision professionals become engaged with spreading decision skills to youth4 for the simple reason that it will make one a better decision professional. Senior executives and ninth graders have about the same attention span (albeit for different reasons) and want to get to the essence simply and clearly. Even when we employ advanced tools, our results should always be made transparent.

Our Profession

What does it mean to be in a profession? A profession differs from a trade. In providing a professional service, we recognize that the customer cannot fully judge our service and must trust the integrity of the professional to act in the customer’s best interest—even when the customer does not wish to hear it. Our customers are the decision makers—the leaders of organizations. We have the responsibility to speak “truth to power.”

We also have the obligation to not “fake it.” Decision professionals must be able to recognize which tools are normative (that is consistent with the norms of decision theory) and which are not but may be useful in practice. We also have to recognize destructive or limited practices. A true decision professional avoids making claims that can be proven to violate the basic norms of decision theory.

As with the medical field, we have to protect our profession from quackery. The profession is beginning to step up to this challenge, taking measures to assure quality and certify competence. This is, of course, a sensitive area in a field that incorporates science, art, and engineering. While I recognize the risks of trying to come to agreement on a definition of decision competence, I support this trend fully and applaud the start that the Society of Decision Professionals has made.

The Biggest Challenge

In this nascent profession, our biggest challenge is to gain greater mindshare among decision makers. The fraction of important and complex decisions being made with the support of decision professionals is still very small. We can make faster progress if we unify our brand and naming conventions. I urge all practitioners to use a common language to make more headway with our audiences.

Here are my suggestions:

- Let’s call ourselves “decision professionals” instead of decision analysts, decision consultants, decision advisors, decision facilitators, and so on.

- Let’s use the term “decision quality” as the overall name that combines getting to the right answer via DA and gaining organizational alignment via process leadership, decision facilitation, and other soft skills.

- Let’s refer to DA as the field that provides decision professionals with the analytical power to find the best alternative in situations of uncertainty, dynamics, complex preferences, and complex systems. The use of the term “DA” also means we will be consistent with the norms of decision theory—usually with a single decision-making body—whose preferences are aligned.

- Multiparty decisions—negotiation, collaboration, competition (game theory)—need to become a part of the decision professional’s domain of expertise, whether or not these areas are considered a subset of or adjacent to DA.

- Decision professionals frequently act as mediators and facilitators with “soft skills” to lead decision processes to reach sound conclusions and to gain alignment and commitment for action. While these skills are not usually considered a part of DA, they are as crucial as model building to the decision professional.

On behalf of the profession, I would like to express my gratitude to Greg Parnell, Steve Tani, Eric Johnson, and Terry Bresnick for creating this handbook. This handbook represents a valuable contribution to the practitioner community. I expect that it will be the first edition of many to come.

CARL SPETZLER

Notes

1Frank Koch in a written response to the question: What is the ROI of investing in DA based on your experience at Chevron? Frank Koch retired in 2010 after the Chevron team had been awarded the best practice award for 20 Years of DA at Chevron.

2See the SDG white paper, Chevron Overcomes the Biggest Bias of All (Carl Spetzler, 2011). Available from SDG website, http://www.sdg.com.

3See: http://www.decisionprofessionals.com

4Check out The Decision Education Foundation at http://www.decisioneducation.org.