CHAPTER FIVE

Use the Appropriate Decision Process

If you can’t describe what you are doing as a process, then you don’t know what you are doing.

—W. Edwards Deming

5.1 Introduction

This chapter presents how to choose the appropriate process to provide decision support to senior decision makers who have the responsibility and authority to make an important decision for their organization or enterprise. We address several questions. What is a good decision? How much time and effort should be devoted to the decision? Who should be involved in making the decision? How should the decision process be structured?

We first discuss the goal of any decision process—making good decisions. We present a definition of a good decision using the six essential elements of decision quality. We describe four common decision processes: two that we believe are best practices and two that have major flaws. Then we discuss choosing a decision process that fits the decision situation. For the most difficult decisions, we recommend the dialogue decision process. We describe the decision processes used in the illustrative examples. We close the chapter with a discussion of making decision quality a way of life in organizations.

5.2 What Is a Good Decision?

The fundamental goal of any decision professional is to help others make good decisions. But how do we know if a decision is good or bad? It is tempting to define a good decision as one that turns out well—that is, one that has a desirable outcome. But this definition is not really helpful because of two deficiencies. First, it states that the quality of the decision may depend on factors beyond the control of the decision maker. Following this faulty definition, we would judge a decision to pay $1 for a 50–50 chance of winning $10 to be good if the prize is won but bad if the prize is not won. In other words, if two people make exactly the same choice in this situation, we might judge one choice to be good and the other to be bad. We want the definition of a good decision to be such that it depends only on factors that the decision maker can control. The second deficiency of the definition is that it requires us to wait for the outcome of the decision to be known in order to judge the quality of the decision. For major strategic decisions, the wait might be many years. We want a definition that allows us to judge the quality of the decision at the time that it is made.

5.2.1 DECISION QUALITY

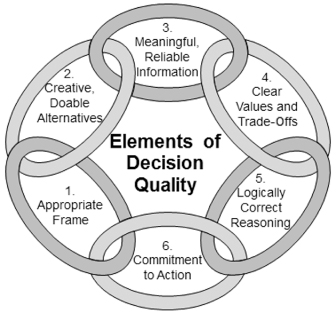

In Chapter 1, we describe a good decision as one that is logically consistent with our preferences, our alternatives, and our assessment of the uncertainties. But how can a decision analyst know when such logical consistency is present? One approach for defining a good decision that has been used successfully over many years of decision consulting is embodied in the decision quality chain shown in Figure 5.1 (Matheson & Matheson, 1998). A good decision requires high quality in each of six essential elements:

FIGURE 5.1 Six elements of decision quality.

5.2.2 THE SIX ELEMENTS OF DECISION QUALITY

The six elements of decision quality are shown as links in a chain to emphasize that the decision is only as good as the weakest link. A good decision must be strong in all six elements.

5.2.3 INTUITIVE VERSUS DELIBERATIVE DECISION MAKING

Often, as discussed in Chapter 2, decisions are made not on the basis of careful deliberation but on the basis of intuitive “gut-feel.” This can be a reasonable approach when the decision maker has made similar decisions previously, has received good timely feedback on their outcomes, and has no motivational involvement with the decision at hand (Campbell & Whitehead, 2010; Kahneman & Klein, 2010).

But for difficult decisions with complex preferences, major uncertainties, and important consequences, making decisions based entirely on intuition is not a useful process. For one thing, a person’s intuition is fallible—a choice made intuitively might simply be a bad choice. Second, if the decision is to be made by a group of people within an organization, it is generally difficult for one person to convince the others of a choice based on “gut feel.” Third, for complex problems, no one person has an intuitive understanding of the complete problem. It is useful to combine the intuition and experience of many experts into a composite understanding of the decision.

Although making decisions entirely on the basis of intuition is not a good idea, intuition can play a valuable role in decision making. If a choice that is about to be made does not “feel” right, it is worth exploring why that is so. Using the six elements of decision quality as a checklist can be very helpful. Perhaps the decision is framed inappropriately. Or perhaps the choice is being made with inadequate attention paid to exploring alternatives. Or the decision is being made on the basis of too little information or value measures that do not truly reflect the decision makers’ preferences. Or there are logical flaws in the analysis. Or the decision makers are not fully committed to implementing the decision. Going through this checklist may reveal why the decision does not “feel” right and point the way to improving the decision. But if the checklist review does not reveal any weakness in the decision and yet it still feels wrong intuitively, it may be one of those times when one’s intuition is incorrect and needs to be educated.

5.3 Selecting the Appropriate Decision Process

In this section, we begin by describing how to tailor the decision process to the decision. Next, we present two decision processes that are best practices—the dialogue decision process (along with the derivative system decision process) and decision conferencing. Then we describe two types of flawed decision processes that are nevertheless in common use—strictly analytical processes and advocacy processes.

5.3.1 TAILORING THE DECISION PROCESS TO THE DECISION

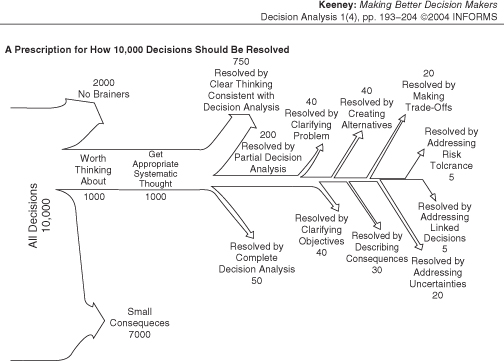

It is fair to ask whether it is appropriate to perform a full decision analysis effort on all decision opportunities, and the answer is no. Ralph Keeney suggests in Figure 5.2 how 1000 decisions that deserve some thinking should be resolved (Keeney, 2004). He suggests that a full decision analysis be done for only 5% of these decisions, and a partial decision analysis for 20% of them. The remaining 75% can be resolved simply by clear thinking that is consistent with decision analysis.

FIGURE 5.2 Suggested prescription for resolving decisions.

(Reprinted by permission, Keeney RL, Making better decision makers, Decision Analysis, volume 1, number 4, pp. 193–204, 2004. Copyright 2004, the Institute for Operations Research and the Management Sciences (INFORMS), 7240 Parkway Drive, Suite 300, Hanover, MD 21076 USA.)

Clearly, the process that an organization uses to make a decision must be tailored to both the organization and the decision. Answers to three key questions will guide the selection of the appropriate process.

5.3.1.1 How Urgent Is the Decision?

The timeframe available for making the decision may be of overriding importance in choosing how it is made, particularly if that timeframe is very short. In an emergency, for example, we simply may not have the luxury of time to give full consideration to which alternative is optimal. Even if the timeframe is measured in days rather than minutes, the press of time may curtail the process that we would ideally want to use. So, we must choose a process that results in a timely decision.

5.3.1.2 How Important Is the Decision?

The degree of importance of the decision should dictate the level of effort devoted to making it. A useful rule-of-thumb is the one percent rule, which states that one should be willing to spend 1% of the resources that will be allocated in a decision to ensure that the choice is a good one. So, for example, when deciding on the purchase of a $1000 household appliance, one should be willing to spend $10 to gather information that could improve the choice. By the same token, a company deciding on a $100 million investment should be willing to spend $1 million to ensure that the investment decision is made well.

Failures commonly occur in both directions. Some very important decisions are made with far too little effort given to making them well. And sometimes, far too much effort is inappropriately expended to make relatively minor decisions.

5.3.1.3 Why Is This Decision Difficult to Make?

As stated in Chapter 2, the degree of difficulty in a decision can be characterized in three different dimensions of complexity—content complexity, analytic complexity, and organizational complexity. A decision that is difficult in only one of these dimensions calls for an approach that is specific to that dimension. A decision that has only content complexity can be made well by collecting and analyzing the required information. A decision that has only analytic complexity can be made well through good analysis. And a decision that has only organizational complexity can be made well with excellent facilitation techniques (see Chapter 4). But a decision that is difficult because it is complex in two or three of the dimensions calls for a carefully designed process.

5.3.2 TWO BEST PRACTICE DECISION PROCESSES

5.3.2.1 Dialogue Decision Process.

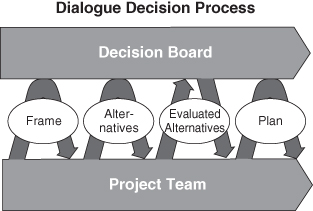

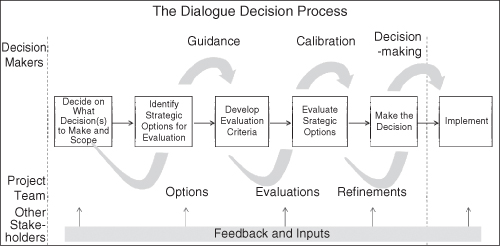

The dialogue decision process (Spetzler, 2007) has been successfully applied within hundreds of organizations to achieve good decision making in the face of content, analytic, and organizational complexities. As its name suggests, the process centers on a structured dialogue between two teams: (1) A team of decision makers, here called the decision board, and (2) a team created to assist the decision makers, here called the project team. The process is shown in Figure 5.3. Taken together, the arrows in this figure are suggestive of a snake, so the process is sometimes informally referred to as “snaking.”

FIGURE 5.3 The dialogue decision process.

The decision board should comprise those people whose agreement is both necessary and sufficient for the decision to be made and successfully implemented. A failure mode to avoid is to exclude from the decision board someone whose veto could block the decision. On the other hand, the decision board should not include anyone whose agreement is not needed to make the decision. Scheduling meetings of the decision board is generally a major challenge, and the more members on the board, the more difficult the scheduling task. Typically, decision board members are asked to commit the time to attend three or four meetings, each of 2–3 hours duration, during a period of 2–4 months.

The project team consists of staff members from the organization who collectively possess the skills to conduct the dialogue decision process, have access to key information sources (including key stakeholder and subject matter experts) required to make the decision, and have the credibility and trust of the decision board members. The project team may also include decision professionals who are internal or external consultants. At least one of the internal members of the project team should commit to work full-time on the decision for the duration of the process, and the remaining members should commit to be involved at least half-time. The project team should have enough members to give it sufficient capacity to carry out its responsibilities, but not so many members that their time is used inefficiently. People who are needed for only one specific part of the process, such as some subject matter experts, need not be on the project team but rather can meet with the team as needed.

The dialogue decision process centers on a typical sequence of 3 or 4 meetings between the decision board and project team, driven by specific deliverables made up of a subset of the six elements of decision quality.

5.3.2.2 First Decision Board Meeting: Frame.

At the beginning of the project, the decision board must be in agreement that the decision being addressed is appropriately framed. Sometimes, this is done by a distinct frame-review meeting; other times by one-on-one interactions. Either way, decision board members discuss the frame for the decision as proposed by the project team, amend it as appropriate, and finally approve the frame as amended. The frame should provide clear answers to the following questions: What is the problem or opportunity being addressed in this decision? What range of choices are within scope for this decision and what possible actions are outside the scope? What value metrics should be used to compare the possible alternative courses of action? What risk factors need to be accounted for in this decision? What is the timeframe for making the decision? Who should be involved? (See Chapter 6 for a full discussion of framing a decision and Chapter 7 for the development of value metrics.)

5.3.2.3 Second Decision Board Meeting: Alternatives.

Following the agreement on frame, the project team works to identify and develop the full range of decision alternatives within the agreed-upon frame. Emphasis is placed on using creativity-enhancing techniques to help identify possibly great alternatives that might be difficult to see initially. Each alternative is checked to ensure that it is both feasible and attractive. (See Chapter 8 for a full discussion of generating good alternatives.) After confirming that the alternatives are consistent with the agreed-upon frame and that the set of alternatives span the decision space, the project team presents them to the decision board, who may eliminate some from further consideration and may suggest new alternatives. By the end of this meeting, the decision board and project team will have agreed on the set of alternatives to be carried forward for evaluation.

5.3.2.4 Third Decision Board Meeting: Evaluated Alternatives.

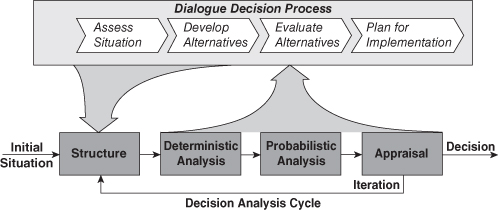

The Project Team then embarks on the task of evaluating the defined set of alternatives. This task typically requires the creation of an analytic structure, including a quantitative model for comparing the alternatives and the collection of relevant information to support the assessment of inputs for the model. (See Chapters 9, 10, and 11 for full discussions on conducting the analysis to evaluate alternatives.) The decision analysis cycle provides a logical framework for the analysis of alternatives (see Figure 5.4). The goal of the analysis is to create insight and understanding of which alternative is best and why it is better than the others. A crucial step at this point in the process is to use the insights gained from the evaluation of the initial set of alternatives to create new “hybrid” alternatives that may be superior to any of the original alternatives. Calculating the value of obtaining additional information to reduce key uncertainties may stimulate the creation of valuable hybrid alternatives.

FIGURE 5.4 The decision analysis cycle.

The project team presents to the decision board the insights gained from the evaluation of the alternatives. This might be done in one meeting or it might be done in two, particularly if the analytic results are complex and require additional time to fully “digest.” In this case, the first presentation of results is in the spirit of inquiry, to familiarize decision board members with its content, probe for weaknesses in the analysis, and for ways that the analysis and/or the alternatives could be improved, and reach agreement on additional work to be done. Alternatively, one-on-one briefings can be made to decision board members to allow them to preview the analytic results and to ask questions in private. These briefings also help the Project Team understand what issues are likely to come up and prepare to address them constructively prior to the final decision meeting.

Chapter 13 discusses the presentation of decision analysis results to decision makers in the spirit of enlightenment. The goal at this point of the process, whether done in one meeting or two, is to have the decision board members agree on the course of action to be undertaken—that is, to have the decision board make the decision.

5.3.2.5 Fourth Decision Board Meeting: Implementation Plan.

Once the decision board has chosen a course of action, planning for its implementation should be done. Depending on the situation, the decision board may or may not meet once again to review and approve the implementation plan. Chapter 14 describes the activities in decision implementation.

In addition to having formal meetings with the decision board, it is always a good practice for project team members to have more frequent, informal communication with the decision makers when that is possible. Such communication would improve the dialogue on the decision and provide more timely feedback on important issues to resolve.

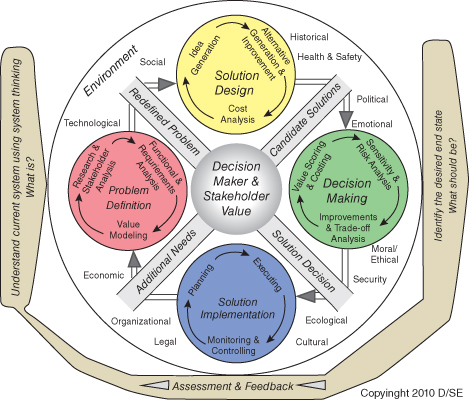

The systems decision process (Parnell et al., 2011) is an example of the dialogue decision process tailored for system decision making performed by systems engineers and program managers responsible for large complex systems. Figure 5.5 provides a graphic of the systems decision process.

FIGURE 5.5 Systems decision process.

The systems decision process is designed to be used to make the decision for a system to proceed from its current stage to the next stage in the life cycle process. For example, it could be used to approve the system concept that will proceed into system design. The phases of the systems decision process map directly to the steps of the dialogue decision process: the systems decision process uses problem definition for framing, solution design to develop alternatives, decision making to evaluate alternatives, and solution implementation to plan for implementation. The project team is called the system design and analysis team, while the decision board is made up of the decision makers and key stakeholders responsible for approving the system design for the next life cycle stage. Furthermore, the spokes of the diagram define the interaction points with the decision makers and stakeholders. Also similar is the use of a decision analysis value model to determine the best design solution. The systems decision process also includes a list of the potential environmental factors that may be important to the decision.

5.3.2.6 Decision Conferencing

Another best practice decision process is decision conferencing, which is described in detail in Appendix C. In a decision conference, decision makers and stakeholders work together in an intensive 2- to 3-day session under the guidance of skilled facilitators to identify key issues, evaluate alternatives, reach decisions, and plan implementation. Required information is elicited directly from the participants rather than derived from external data sources. A simple value model is developed during the session to help evaluate and compare alternatives.

Larry Phillips (Phillips, 2007), a highly experienced leader of decision conferences, identifies three reasons why decision conferencing is valuable: (1) it helps decision makers and stakeholders create a shared understanding of the issues; (2) it develops a sense of common purpose among the participants; and (3) it fosters a commitment among the participants on the way forward.

Decision conferencing is most useful for decision situations in which there is a clear sense of urgency so that all key participants are willing to devote the time and effort required and in which the chief challenge is in gaining agreement and commitment of the decision makers rather than in overcoming difficult analytic and content challenges.

Decision conferencing and the dialogue decision process are often combined in a series of intensive workshops interspersed with intensive “homework.” This approach has been especially useful with teams that are geographically dispersed.

5.3.3 TWO FLAWED DECISION PROCESSES

Next, we describe two common types of decision processes that have major flaws.

5.3.3.1 Strictly Analytical Decision Processes.

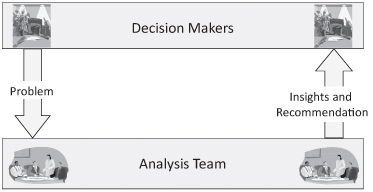

The focus of a strictly analytical process is on the technical complexity of the decisions and not the organizational complexity. Typically, this approach uses complex analytic models to compare the existing alternatives. Generation of additional alternatives may or may not receive appropriate attention. Interaction with decision makers and key stakeholders typically occurs only at the start and end of the process. The final presentation provides analytic insights about the alternatives. But since the decision makers and stakeholders have not participated in the process, they may raise issues or alternatives that were not considered in the analysis. Furthermore, they may not be willing to accept the results of an analysis that they consider a “black box” and do not understand. Thus, a strictly analytical process may result in “spinning wheels,” a situation in which the decision point is never reached because the process is endlessly cycled. Figure 5.6 is a diagram of a strictly analytical process.

FIGURE 5.6 Strictly analytical process.

5.3.3.2 Advocacy Decision Processes.

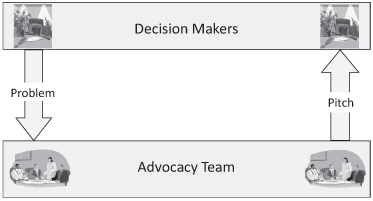

The second flawed type of decision process is the advocacy process. In this process, an advocate (who may be just one person or a group of people) prepares a presentation to the decision makers with the goal of convincing them to undertake a particular course of action. The advocate is a “champion” of the recommended course of action, either because he or she believes that it is best for the organization or for other reasons.

The advocacy process shares with the strictly analytical process the flaw that decision makers are presented with a recommendation that they were not involved in exploring and evaluating. Their role in the advocacy process is to try to identify the weaknesses of the recommended course of action and to either accept or reject the “pitch.” The advocacy process has two additional unique flaws. First, possible alternatives to the recommended course of action are generally not presented for consideration to avoid unwanted distraction from the advocated course of action. Second, the analysis supporting the advocated actions tends to focus on its upside and minimize its downside, with information that is unfavorable to the recommendation being downplayed or omitted. Figure 5.7 illustrates the advocacy process.

FIGURE 5.7 Advocacy process.

5.4 Decision Processes in Illustrative Examples

See Table 1.3 for further information on the illustrative examples. In all three illustrative examples, the decision process had to be determined.

5.4.1 ROUGHNECK NORTH AMERICAN OIL STRATEGY

Roughneck Oil’s North American division owned or controlled assets that could lend themselves to a variety of energy-related businesses, including:

- Conventional oil and gas exploration and production

- Enhanced oil recovery

- Coalbed methane

- Tar sands

- Power generation.

The dialogue decision process was used for this decision. The project was initiated by the Roughneck North American VP, who identified his boss, the SVP for The Americas, as the final decision maker. The North American VP invited six additional functional area leaders (conventional exploration and production, marketing, enhanced oil recovery, facilities, business development, and strategy) under that SVP to join the decision review board.

In consultation with an external decision analysis team (consultants), the Roughneck North American VP created the core team, comprising 40 key contributors in key functional areas. He asked the core team to frame the project around their concerns, and asked them to work together throughout the project. There had been two previous decision analysis projects, so a few of the participants were familiar with the process, but it was new to many of them.

5.4.2 GENEPTIN PERSONALIZED MEDICINE

As a growing biotech company, DNA Biologics was transitioning its decision making process. Historically, it had relied on informal, experience-based decision-making process. As it matured, it started to adopt a more formal, analysis- and consensus-based decision approach—the dialogue decision process shown in Figure 5.8, which is a variation of the process described in Section 5.3.2.1. The project team worked with decision makers and other stakeholders within the organization to establish shared ownership, alignment, and fact-based decision making to achieve consensus on the best decision strategy.

FIGURE 5.8 The Geneptin dialogue decision process.

For the Geneptin decision, the decision board comprised the two joint decision makers: the VP of Drug Development and the VP of Commercialization. The project team was headed by a program team leader, and included members from multiple functional areas, including commercial (global/strategic marketing), clinical development, pricing and market access, biomarker development, regulatory, medical affairs, and business development (for potential diagnostic partnership aspects).

5.4.3 DATA CENTER

The government agency needed to be able to justify the data center location decision to budget approvers in the executive branch and the Congress. In addition, the decision had to be defensible to explain the decision to governors, senators, congressmen, and mayors in locations not selected. Multiple agency directorates were involved in the decision: technology (design the mission applications), mission (operate the mission applications), information technology (operate data center and communications), and logistics (design and acquire the facilities, power, and cooling). There would be multiple approval levels to obtain the funds and approve the location decision within and outside of the agency. The agency director and deputy director were the decision makers.

The agency did not have a process to decide the location of the next data center. Based on the recommendations of agency advisors, the systems decision process was used. A senior executive was assigned to lead the project team. About 25 experts from all the key organizations were assigned to the team. The decision analysis was performed by two decision analysts on the team. With the exception of the decision analysts, the project team did not have experience with the systems decision process.

5.5 Organizational Decision Quality

This chapter discusses the choice of an appropriate process for making single decisions. Often, however, an organization that has realized the benefits of high quality in several important decisions will strive to routinely achieve that quality in all of its decision making. This goal is given the name organizational decision quality (ODQ). Carl Speltzler (Spetzler, 2007) states five criteria by which one can judge whether an organization has reached this goal:

Achieving organizational decision quality requires the concerted efforts of many people over a period of many years (perhaps 5–10), with systematic training programs and repeated application of decision analysis processes. The path is long and the investment high, but organizations that have achieved the goal report that the rewards easily justify the investment.

5.6 Decision Maker’s Bill of Rights

The Society of Decision Professionals (SDP) has published a document called “The Decision Maker’s Bill of Rights”1 that states the expectations that any decision maker should have. Among the several variations of the document is the following:

The decision maker Bill of Rights is an excellent way to engage the key decision makers at the beginning of a decision analysis project to help them understand why they benefit directly from the use of the decision processes recommended in this chapter.

5.7 Summary

Our overall goal in the decision process is to help senior leaders make good decisions, where goodness is defined by the six essential elements of decision quality. We describe the dialogue decision process as a best practice that can be used to achieve consistently good decisions in the face of complexity of three different types: content complexity, analytic complexity, and organizational complexity. We also describe decision conferencing as a best practice that is useful for urgent decision situations in which decision makers and key stakeholders are willing and able to work together intensively for a few days, using only readily available information and fairly simple analytic structures.

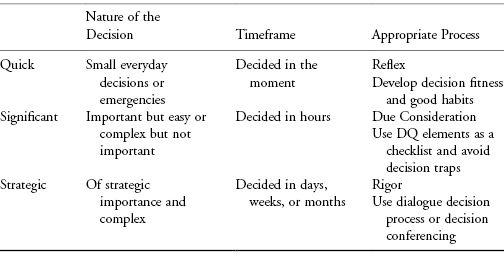

Both the dialogue decision process and decision conferencing require a significant investment of time and effort and therefore should be used only for those decisions where such an investment is justified. Table 5.1 suggests the process that is appropriate for each type of decision.

TABLE 5.1 Fitting the Process to the Decision

KEY TERMS

Note

1The Bill of Rights was conceived by Jim Felli and Jay Anderson of Eli Lilly and Company.

REFERENCES

Campbell, A. & Jo Whitehead, J. (2010). How to test your decision-making instincts. McKinsey Quarterly, May, 1–4.

Kahneman, D., & Klein, G. (2010). Strategic decisions: When can you trust your gut? McKinsey Quarterly, 2, 58–67.

Keeney, R.L. (2004). Making better decision makers. Decision Analysis, 1(4), 193–204.

Matheson, D. & Matheson, J. (1998). The Smart Organization. Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

Parnell, G., Driscoll, P., & Henderson, D. (eds.). (2011). Decision-Making in System Engineering and Management, 2nd ed. New York: John Wiley & Sons.

Phillips, L. (2007). Decision conferencing. In W. Edwards, R. Miles, & D. von Winterfeldt (eds.), Advances in Decision Analysis, pp. 375–399. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Spetzler, C.S. (2007). Building decision competency in organizations. In W. Edwards, R. Miles, & D. von Winterfeldt (eds.), Advances in Decision Analysis, pp. 451–468. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.