CHAPTER SIX

Frame the Decision Opportunity

A pessimist is one who makes difficulties of his opportunities and an optimist is one who makes opportunities of his difficulties.

—Harry S. Truman

Opportunities multiply as they are seized.

—Sun Tzu

6.1 Introduction

The decision frame is the lens that we use to view the decision problem or opportunity. We believe that a good decision frame is critical to decision quality (see Chapter 5). Creating a good frame is the first task that a decision practitioner should undertake when working on a decision. Almost every decision process begins with a step that focuses on describing the decision problem or the decision opportunity. As described in Chapter 5, the dialogue decision process begins with “decision framing.” Decision framing is the first step in decision quality. Clemen and Reilly’s decision analysis process flow chart begins with “Identify the decision situation and understand objectives” (Clemen & Reilly, 2001). The scalable decision process begins with “defining the problem or opportunity” (Skinner, 2009). The systems decision process begins with “problem definition” (Parnell et al., 2011).

Inadequate or poor framing is an all-too-common cause of failure to achieve good decision making within an organization. When postmortems are conducted on decisions that have “gone wrong,” the reasons identified for failure frequently point back to low quality in the framing of the decisions. “We did a great job of solving the wrong problem.” “We couldn’t agree on a path forward within the short timeframe that we had.” “We failed to involve a key decision maker and he vetoed the recommendation.” “We didn’t talk to all of the key stakeholders and didn’t have a full understanding of the key issues.” “We overlooked an important nonfinancial objective, so the decision makers were not willing to accept the results of our analysis.” “We tried to solve all of the company’s problems instead of focusing on the most important ones and we never got anywhere.”

In effect, the frame defines the decision that is being made. The frame makes clear which possible courses of action may be considered as part of the decision and which may not. The frame specifies when the decision must be made, and it identifies the measures by which the potential outcomes of the decision should be evaluated. The frame guides us regarding who should be involved in making the decision.

Remember that there is no objectively “correct” frame for any decision situation. Rather, the right frame is one that is explicitly approved as appropriate by the decision makers. That is why the first meeting of the decision board in the dialogue decision process (see Chapter 5) is devoted to reaching agreement on the framing of the decision.

In this chapter, we begin by discussing how a decision is declared (Section 6.2). We then discuss what constitutes a good frame for a decision (Section 6.3) and describe a number of best practices for achieving good decision framing (Section 6.4). We conclude with a description of how the decisions were framed in the illustrative examples (Section 6.5).

6.2 Declaring a Decision

Before a decision can be framed, someone must declare that the decision needs to be made. All too often a worry festers, but no one takes the step to declare that alternatives should be formulated and action taken. Sometimes, it can be a great service to someone facing such a situation to initiate a conversation that leads to the idea that a decision should be made.

It is quite possible that the mere declaration of a decision will lead the person to formulate an excellent alternative, which he or she can then confidently choose, without further ado; no extensive analysis required! Sometimes, a brief discussion of objectives can clarify the issue, and, again, enable a quick decision to be taken without extensive process.

On other occasions, the decision maker may be tempted to “trust their gut,” but this may lead to low quality in the decision. Several authors (Kahneman & Klein, 2010), (Campbell & Whitehead, 2010) point out that if the decision maker has not received good feedback on previous analogous decisions, or has some motivational involvement with this one, deciding without more structured thought is problematic. It can be a great service to help someone in this situation formulate the intention to articulate objectives, generate alternatives, and ascertain which alternatives meet the objectives best. This conversation is an ideal time to help the person formulate a vision statement (see Section 6.4) for a decision process, and begin thinking about the resources required to realize the vision.

6.3 What Is a Good Decision Frame?

We often use the analogy of framing a photograph when discussing decision framing. An experienced photographer carefully frames a photograph to focus the viewer’s attention on those features of the subject that the photographer believes are of greatest importance. In doing this, the photographer consciously excludes some features of the situation and includes others within the frame. The framing of the photograph creates a specific perspective on the subject—long-distance view versus close-up and wide-angle versus telephoto view.

A decision frame specifies three key aspects of the decision:

The purpose of the decision may also include a specification of when the decision must be made, particularly if the choice must be made urgently. For example, the purpose of a decision might be to choose whether or not to exercise an option before it expires 2 days from now.

And finally, the purpose of the decision should make clear which consequences of the decision are important. In other words, the frame should specify which value measures should be used to compare alternatives. For example, the purpose of a decision might be to choose the method of producing the new product that achieves the best trade-off between financial profit and environmental impact.

With a clear perspective on the decision situation, the frame informs which issues need to be addressed and helps identify which people should be involved in making the decision.

6.4 Achieving a Good Decision Frame

The fundamental requirement to achieve good framing of a decision is communication—well-structured and effective communication among those involved in making the decision and the key stakeholders. Three major communication techniques are interviews, surveys, and facilitated groups (See Chapter 4 for a full discussion of the advantages and disadvantages of each technique). In practice, we use a combination of these techniques. A highly recommended way to foster good communication is to conduct a framing workshop. This event is typically an all-day session, or even a multiday session, involving perhaps 15–20 people who are the decision makers, subject matter experts, and other stakeholders or their appointed representatives. If scheduling constraints make such a workshop impossible, it can be conducted in several shorter sessions or key individuals who are not able to attend may be interviewed.

The suggested agenda for the framing workshop is as follows:

6.4.1 VISION STATEMENT

Creating a vision statement for the decision is an effective way to make sure that there is agreement on the purpose of the decision among the decision maker(s) and key stakeholders. The vision statement1 answers three questions:

A good way to create the vision statement is to solicit and display answers to each question from all workshop participants. Eliminate duplications among the responses and then discuss substantial differences in the answers, trying to reach consensus on them. If necessary, appeal to the decision makers for final resolution of differences. Once consensus is reached on the key thoughts in the statement, have a volunteer work offline to find a concise but clear way to express the vision statement.

The vision statement refers to the process of making the decision, NOT the consequences of the decision. So, the third question (“How will we know that we have succeeded?”) should be understood to mean success at the time the decision is taken, not when the final outcome is known. Workshop participants may be tempted to include their desired solution in the criterion of success. Highlighting this issue up front can help combat this tendency when it arises. An example of a Vision Statement is shown in Figure 6.1.

FIGURE 6.1 Example vision statement.

It may be tempting to skip working on the vision statement because “Everyone knows what this decision is about.” If that is the case, then creating the vision statement will take only a few minutes. But the vision statement exercise may reveal unsuspected differences of opinion about the purpose at hand. These differences must be resolved so that there is full agreement on the purpose. Otherwise, the entire decision effort may be doomed to failure.

6.4.2 ISSUE RAISING

A central step in framing a decision is issue raising. When successfully done, issue raising brings to light all of the many perspectives that can be used to view the decision situation and lays the groundwork for creating a good decision frame.

Issue raising can be enhanced by the active participation of everyone in the framing workshop under the guidance of a skilled facilitator (see Chapter 4 for discussion of facilitator skills and techniques). The facilitator makes sure that all participants understand the purpose of the decision, as declared in the vision statement. Then each participant is asked to write down (in silence) as many issues as come to mind that bear on the decision situation. An issue is any statement or question relating to the situation at hand. The facilitator should insist that each issue be expressed as a complete sentence or question. So, “market share” is not a valid issue statement, but “Our market share is falling.” is a valid issue statement. If possible, each issue should be written on a large Post-it® note. After participants have had sufficient time to write their issue statements (say, 5–10 minutes), the facilitator asks one participant to read one of his or her issue statements. No discussion of the issue statement is permitted, except for questions of clarification. If Post-it notes are used, the issue is placed on the wall. Otherwise, it is recorded in a computer document that is projected and visible to all. The facilitator then selects other participants in turn to each read one issue statement. As issues are placed on the wall or in the computer document, attention is paid to grouping related issues together. After all issue statements have been read and posted, the facilitator asks the participants to review the issues and reflect on them. This may lead to the identification of additional issues, which are then added to the original set.

Working with scenarios may help to enrich the set of issues. To do this, the facilitator divides the group into small teams and assigns a scenario to each. The scenarios, which are prepared in advance, portray significantly different possible futures that could strongly impact the outcome of the decision at hand. Each team is asked to raise issues that would be relevant within their assigned scenario. These are then collected when the teams are brought back together and added to the issues previously raised.

For a major decision situation, the number of issues raised is typically more than one hundred. The facilitator may appoint a subteam to review all of the issue statements and to make sure that they are appropriately grouped by theme.2 Duplicate issue statements may be consolidated.

The facilitator may also have participants vote on which issues they think are most important to address in reaching a good decision. This will give some sense of priority ordering of the issues, but no issue should be discarded from consideration at this stage.

The following are suggested good practices for issue raising:

- Make sure that participants representing as many diverse perspectives as possible are in the workshop.

- Make sure that everyone’s issue statements are heard.

- Remind participants that issue raising is just an early step in the decision process, not a search for the solution.

- Allow plenty of time for issue raising—1–3 hours.

- Prohibit judgmental statements about issues.

- Strive for a goal of quantity, not quality.

6.4.3 CATEGORIZATION OF ISSUES

After the many issues are raised, they should be categorized into four groups

- Decisions. Issues suggesting choices that can be made as part of the decision.

- Uncertainties. Issues suggesting uncertainties that should be taken into account when making the decision.

- Values. Issues that refer to the measures with which decision alternatives should be compared.

- Other. Issues not belonging to the other categories, such as those referring to the decision process itself.

For many issue statements, categorization is clear. For example, the statement “We need to expand our productive capacity” is a decision issue, while the statement “When will our competitor introduce an upgraded product?” is an uncertainty issue. But some issue statements are more difficult to categorize. For example, consider the issue statement “Can we use new technology to reduce production costs?” This might be viewed as an uncertainty about the impact of new technology on production costs. Alternatively, it might be viewed as a decision about whether to install new technology. The context of the situation may make it clear that one of these interpretations is relevant and the other is not, or, it may be that both are relevant. If so, the one issue statement should be split into two statements that are placed in separate categories.

Once the issues have been categorized, they are used to inform later steps in the decision process. The decision issues provide the basis for defining the scope component of the decision frame (see decision hierarchy, below) as well as serve as raw material for the creation of alternatives (see Chapter 8). The uncertainty issues provide a checklist to be used when developing the analytic structure for evaluating alternatives (see Chapters 9 and 11). The value issues likewise provide a checklist for defining the measures used in evaluating the decision alternatives (see Chapter 7).

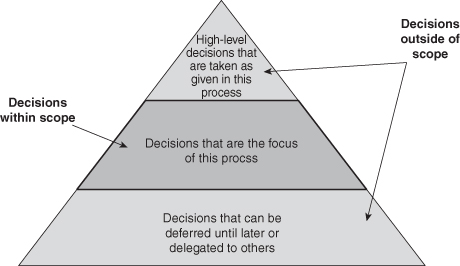

6.4.4 DECISION HIERARCHY

The decision hierarchy is a valuable conceptual tool for defining the scope of the decision. The decision hierarchy (see Fig. 6.2) is portrayed as a pyramid structure with three levels to which are assigned the many possible choices that might be part of the decision at hand. The topmost level is for those high-level context-setting choices that are out of scope because they are assumed to have been made already. For the purposes of the decision at hand, we “take as given” the choices in the top level of the hierarchy. For example, in a decision focused on the manufacturing strategy for a product line, the choice of whether or not to keep that product line as a company offering might be assigned to the top level of the hierarchy—we take as given that the company will continue to make and sell the product line.

FIGURE 6.2 Format of the decision hierarchy.

The middle level of the decision hierarchy contains those choices that are inside the scope of the decision under consideration. Different combinations of these choices will be defined as alternatives for the decision.

The lowest level of the decision hierarchy has choices that are outside the scope of the decision because they can be deferred until later and/or delegated to others. These might be quite important choices that are separable from the decision under consideration. Or they might be low-level choices that have very little impact on the overall outcome of the decision.

A good method for creating the “first draft” decision hierarchy is to take all of the issues categorized as decisions and have the team discuss in which level of the hierarchy each one belongs. Make sure to include any decisions that were not mentioned in the issue raising but which are clearly a possible part of the decision situation. The resulting decision hierarchy is preliminary because the decision makers have the final say on where each choice should be.

The decision hierarchy is an effective vehicle for fostering a good conversation about the scope of the decision. And when completed and approved by the decision makers, the decision hierarchy is a clear statement of that scope. Only choices in the middle level of the hierarchy should be considered as part of the decision.

6.4.5 VALUES AND TRADE-OFFS

A part of the framing workshop should be devoted to reaching agreement on the value measures to be used to evaluate and compare alternatives for the decision. See Chapter 7 for a full discussion of values and trade-offs.

6.4.6 INITIAL INFLUENCE DIAGRAM

Depending on the situation, it may or may not be useful to devote time in the framing workshop to creating an initial version of the influence diagram that describes the structure of analysis to be used in evaluating the decision alternatives. Sometimes, creating the initial influence diagram helps clarify the discussion of the decision scope. Or the initial influence diagram can be used to define information-gathering tasks that need to be undertaken immediately. See Appendix B for important background information on influence diagrams. The use of influence diagrams for modeling is also presented in Chapter 9.

6.4.7 DECISION SCHEDULE AND LOGISTICS

The framing workshop, because it usually occurs at the start of the decision process, is a good occasion to establish the schedule for making the decision and to agree on the major tasks and logistical details. The schedule for the decision should be a timetable of steps that lead to making the decision. If the dialogue decision process (see Chapter 5) is to be used, then the dates of the decision board meetings should be established, at least provisionally. The composition of both the decision board and the project team should be agreed upon at this time. If possible, logistical details, such as designating a special meeting space for the project team, should be worked out in the framing workshop.

6.5 Framing the Decision Opportunities for the Illustrative Examples

See Table 1.3 for further information on the illustrative examples. In this section, we discuss the use of decision framing for the illustrative examples and some of the challenges in applying the techniques.

6.5.1 ROUGHNECK NORTH AMERICAN STRATEGY (RNAS)

With the help of an external team of decision analysis consultants, the Roughneck North American Vice President (VP) began the decision analysis project. There had been two previous DA projects, so a few of the participants were familiar with the process, but it was new to many of them. The VP identified a group of 40 key contributors in key functional areas and asked the decision analysis consultants to frame the project around the concerns of this group. The strength of this approach is that it gives voice to various constituencies who may not normally be able to raise concerns at a strategic level.

The first step for RNAS framing was an issue-raising session, in which participants raised their major issues, which the decision analysts then categorized as decisions, uncertainties, objectives, or other. This project illustrates the strengths and weaknesses of bottom-up framing of a decision project. It allowed the VP to “take the pulse” of the various business units, and gave many participants a feeling of inclusion in the process. However, upon reviewing the results, the decision analysis consultants were concerned that addressing them would call for multiple fragmentary perspectives, rather than generating and leveraging a coherent perspective on the business. The VP agreed.

Based on a review of the areas of concern and the kinds of insights desired, the VP asked that the decision analysts redefine their framing as a portfolio resource allocation problem. The portfolio consisted of the three existing business areas (conventional E&P, coal bed methane, and enhanced oil recovery), along with two possible areas of expansion (tar sands, and electric power generation). A decision hierarchy (Fig. 6.3) was developed and used in this project.

FIGURE 6.3 RNAS decision hierarchy.

The vision statement for the project was to “develop the RNAS portfolio investment and divestment strategy to achieve the financial objectives of the firm.”

6.5.2 GENEPTIN PERSONALIZED MEDICINE

In framing the Geneptin decision, the project team developed the decision hierarchy shown in Figure 6.4. For an oncology drug candidate, Geneptin could be explored for many indications during its life cycle. Geneptin, for example, was being explored for the metastatic breast cancer indication, but could also be investigated for such other indications as adjuvant breast cancer and other tumor types. As the result of discussions within the decision team, to simplify and contain the scope of the decision analysis, the project team was instructed to focus the analysis on the metastatic breast cancer indication only. Thus, the key decisions to be addressed by the team were: (1) whether to develop Geneptin as a therapy for all patients with metastatic breast cancer or to pursue a personalized medicine approach; and (2) if Geneptin is to be developed as a personalized medicine, how should the biomarker diagnostic test be incorporated into the Phase III trials.

FIGURE 6.4 Geneptin decision hierarchy.

6.5.3 DATA CENTER DECISION

Three people from the Agency’s advisory board were selected to do the opportunity framing. The decision makers believed that a new data center was needed. At that time, all of the agency’s data centers were located in one area. Several senior leaders viewed this problem as an opportunity to make data center operations more secure by selecting a location outside of this area. There would be multiple approval levels to obtain the funds and approve the location decision within and outside of the agency. The agency needed to select the best data center location and justify the decision to budget approvers in the Executive Branch and Congress.

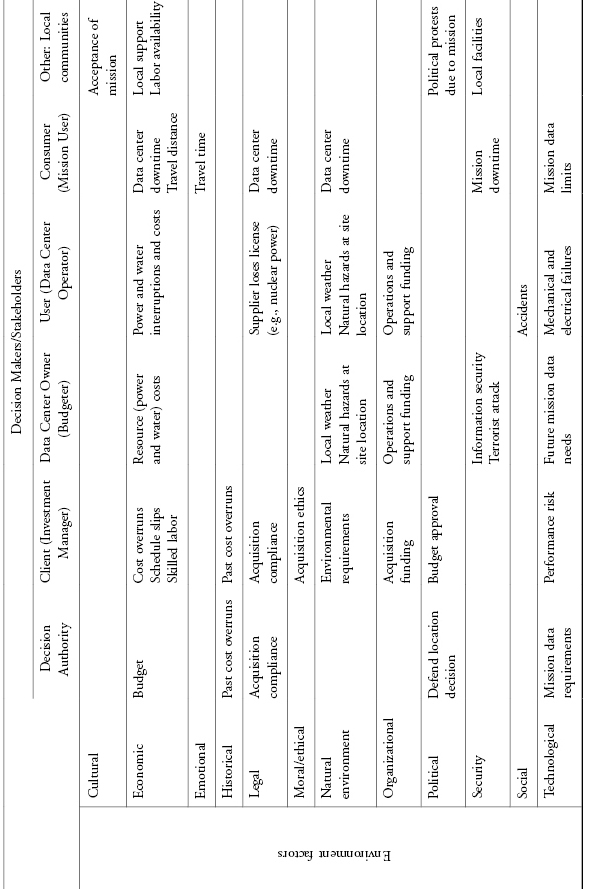

The decision framing team interviewed several key decision makers and stakeholders and identified some key assumptions. First, the full process from site selection to initial operational capability was projected to take at least 3 years. Second, it was decided that the actual IT equipment would be ordered after the site had been selected so the agency could order the latest IT technology. A third assumption was that after the facility became operational, it would be a “lights-out facility” remotely operated by mission managers with minimal support staff on site. Table 6.1 summarizes each stakeholder’s key concerns and location preference.

TABLE 6.1 Concern List by Stakeholder

| Stakeholder | Concerns | Location Preference |

| Agency director | Defensible decision Mission capability Cost |

Out of metro DC |

| Director, board of advisors | Defensible decision Mission capability |

Out of metro DC |

| Mission manager | Mission capability Usable mission floor space Loss of power or cooling Office space Travel distance from DC |

Washington State (Columbia River) |

| IT director | Power Physical security Site accessibility for mission support personnel |

Tennessee (Tennessee Valley Authority) at a National Laboratory location |

| Facilities director | Facilities acquisition cost Power cost |

Existing agency facility in Texas |

| Security manager | Location from nearest road Physical security |

Existing agency facility |

| Data communications manager | Bandwidth (from mission managers in DC to data center) Latency Information security |

Facilities with high bandwidth communication links |

| Power manager | Primary and backup power sources Low cost power |

Any location with reliable, low-cost power |

| Cooling manager | Primary and backup cooling sources Low cost cooling |

Any location with reliable, low-cost cooling |

| Systems engineering director | Clear requirements Use a life cycle cost model |

None |

| Life cycle cost manager | Use life cycle cost model | None |

After the interviews were conducted, an issue identification workshop was held with representatives of the key stakeholders. The stakeholder issue identification matrix in Table 6.2 summarizes the major issues from the interviews and the workshop. The interviews and workshop were effective techniques to get issues from the senior leaders and their key representatives involved in this important agency decision.

TABLE 6.2 Stakeholder Issue Identification Matrix

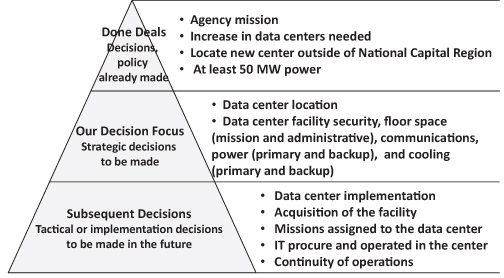

After the interviews and the workshop, the decision hierarchy was developed (Fig. 6.5). The vision statement for the project was to “select the most cost effective large data center location and design for future agency mission support.”

FIGURE 6.5 Data center location decision hierarchy.

6.6 Summary

Achieving a good frame is essential to making a good decision. A decision practitioner should always resist the temptation to “plunge in” and start working on a decision before a clear frame is agreed upon by the decision makers and key stakeholders.

This chapter introduces helpful tools for framing the decision opportunity. The vision statement is an effective tool to obtain agreement on the purpose of the decision analysis. Issue raising is an important technique to involve many key individuals in defining a clear decision frame. The stakeholder issue matrix is also useful for initial thinking about key stakeholders and for summarizing the key issues. The decision hierarchy is a proven technique for clarifying the scope of the decision. These tools should be a part of every decision analyst’s tool kit.

Just as important, a worthy decision practitioner should never think of the decision frame as being permanent. Even if it took considerable time and effort to create the decision frame, it is always possible that the frame will need to be changed during the decision process. Unexpected external developments may occur. Or new information may come to light. Or new insights into the situation may arise. Any of these events may trigger the need to reexamine and possibly change the decision frame. It is good practice to ask periodically during the decision process whether the frame needs to be reexamined.

KEY TERMS

Notes

1Other common names for the vision statement are the purpose statement, opportunity definition, or problem definition.

2Common names for this process are affinity diagramming or binning.

REFERENCES

Campbell, A. & Whitehead, J. (2010). How to test your decision-making instincts. McKinsey Quarterly, May, 1–4.

Clemen, R.T. & Reilly, T. (2001). Making Hard Decisions with Decision Tools. Belmont, CA: Duxbury Press.

Ewing, P., Tarantino, W., & Parnell, G. (2006, March). Use of decision analysis is the army base realignment and closure (BRAC) 2005 military value analysis. Decision Analysis, 3(1), 33–49.

Kahneman, D. & Klein, G. (2010, March). Strategic decisions: When can you trust your gut? McKinsey Quarterly, 2, 58–67.

Parnell, G., Driscoll, P., & Henderson, D. (eds.). (2011). Decision-Making in System Engineering and Management, 2nd ed. New York: John Wiley & Sons.

Skinner, D.C. (2009). Introduction to Decision Analysis: A Practitioner’s Guide to Improving Decision Quality, 3rd ed. Sugar Land, TX: Probabalistic Publishing.