Appendix C

Decision Conferencing

Decisions of the kind the executive has to make … are well made only if based on the clash of existing views, the dialogue between different points of view, the choice between different judgments. The first rule in decision making is that one does not make a decision unless there is a disagreement.

—Peter Drucker, Management: Tasks, Responsibilities, Practices

None of us is smarter than all of us.

—Japanese proverb

C.1 Introduction

The purpose of this chapter is to provide an overview of a specialized group facilitation approach that has been in use since the late 1970s known as decision conferencing. According to the website of the International Decision Conferencing Forum, a professional association of decision conference practitioners, the formal definition of a decision conference is as follows: (IDCF, 2012)

Decision Conferencing is a scientifically-grounded methodology that managers of an organisation can adopt to take decisions as a group. It is basically a series of intense day-long meetings, normally stretching for no more than 2-3 days, attended by all the decision makers that are in one way or the other involved, impacted, or interested in a particular issue requiring a decision. Unique features of Decision Conferencing are the dynamic creation of a mathematical computerized model, normally associated with a few proven Decision Analysis (management sciences) techniques, the absence of any pre-configured schedule and the use of a professional facilitator. The results (decision) are shaped by the group of participants, dynamically and in a way that allows them to see the effects of any individual preference; this reduces conflict and channels positively any individual concerns. The ultimate effect is that the group creates decisions that last, learning along the way from each other.

This approach attempts to combine the best of staff experts and managers from the field that provide substantive expertise, with external facilitators who provide process expertise. The result is a series of intensive meetings that seek to identify key issues, evaluate alternatives, and introduce an implementation mechanism. The overall goal of the conference is to develop informed consensus among key players.

Decision conferencing was introduced by Dr. Cameron Peterson, Director of Decision Analysis at Decisions and Designs, Inc. (DDI) in 1979. According to Dr. Larry Phillips, who brought decision conferencing to the United Kingdom, (Phillips, 2007), Dr. Peterson wanted to change the traditional “doctor-patient” model of consultancy to one in which key people who knew the problem were brought together for an open exchange of information via discussion, to provide relevant data and judgments, and to make decisions. This new model ensured that the customer owned the problem and the solution, while the decision analysts managed the process for the client’s problem solving. Decision conferencing recognized that: (Kuskey, 2004, Overview of Decision Facilitation)

- Most significant decisions require decision-maker judgment regarding options, consequences and value of the consequences, and uncertainty.

- Most significant decisions are made collaboratively, some people bringing technical or policy expertise, some decision-making authority.

- A face-to-face environment provides the best forum for successful collaboration.

- Without effective facilitation, meetings can go on and on without closure

The decision conferencing approach has evolved over years of trying to assist decision makers with time-urgent decision problems. The approach is not one of an external analyst coming in to an agency, gathering data on the facts, taking the problem away for study, and later returning with a recommended decision. Instead, it can be viewed as facilitation of the decision process (O’Connor, 1984), but with the major effort being accomplished in several days through a series of intense group meetings in which key players interact to explore the decision process as well as the decision itself. The expertise of the client organization is absolutely essential for success, and the level of expertise needed is typically that which resides in the heads of business and technical managers. While supporting information is important, it is supplemental to the process rather than being its focus. During the decision conference, computer-based models for multiobjective decision analysis (MODA), for probability analysis, and for resource allocation often are used as a focus for group discussion. The structured conference process allows participants to debate issues constructively while encouraging the group to represent its collective judgments in a logically consistent and easily communicated fashion (Kuskey, 1983). One of the strongest features of a decision conference is that it allows participants to work towards consensus regardless of the individual decision making processes being used by the participants (Kuskey, 2004).

One point needs to be emphasized here. In the subsequent sections, we discuss typical processes and formats for decision conferences, and the information can provide good background for practitioners. That said, the authors have found that there truly is no such thing as a “typical” decision conference. Every conference is unique, and there is no “cookbook” approach to conducting them. The facilitator must be agile enough to react to the unfolding events, and must be prepared to make major changes to the “plan” on the fly. Not only that, each facilitator must work to his or her own strengths—what works for one facilitator may not work for another.

The remainder of the Appendix is organized as follows. Section C.2 and Section C.3 discuss typical formats and facilities and equipment used in decision conferences. Section C.4 introduces group processes. Section C.5 presents advantages and disadvantages of decision conferences. Section C.6 presents best practices. Section C.7 offers a summary.

C.2 Conference Process and Format

Decision conferences can be used for a variety of decisions. First are institutional decision processes that may involve many people over a series of meetings that extend over weeks or even months. Second are routine, one-time responses aimed at a specific topic, such as resource allocation, evaluation of alternatives, or strategic planning that extend over a 1- to 4- week timeframe. Third are quick-response, quick turn-around sessions that leave little time for planning and are completed in hours or days (Kuskey, 2004, Overview of Decision Facilitation).

A typical decision conference consists of a 2- to 3-day session with key players and facilitators, followed by further analysis and reporting. The key players are the client organizational planners, decision makers, and decision implementers who are responsible collectively for the issues under discussion, supported by the facilitation team. The facilitators are professionals who specialize in leading, moderating, model building, and documenting the working sessions. Normally, each facilitator plays a distinct role in the conference. The group leader moderates and controls the sessions, elicits information, asks questions, channels responses, and builds analytical models (often, evaluation and resource allocation models) in response to group input. A second team member implements in real time the computer models1 developed by the group leader. The third team member acts as a conference recorder, documenting all major decisions and providing an audit trail of the decision rationale for the session. Ideally, all team members are qualified to assume any of the three roles. Facilitator teams are also structured to bring to bear a broad base of experience, with a variety of disciplines represented to include decision analysis, business administration, computer science, mathematical and cognitive psychology, engineering, economics, and operations research. Additional desirable characteristics of facilitators include the ability to think quickly and clearly on their feet, strong leadership skills, a results-oriented philosophy, and self-confidence (Ring, 1980).

Larry Phillips (Phillips, 2007) developed a schematic of the decision conferencing process (Fig. C.1):

FIGURE C.1 The decision conferencing process.

(Modified from Phillips, L.D. [2007] “Decision conferencing,” in Edwards, W., Miles, R., & von Winterfeldt, D. (eds.), Advances in Decision Analysis from Foundations to Applications, Cambridge University Press.)

C.3 Location, Facilities, and Equipment

Decision conferences can be and have been conducted at the client’s location, an off-site location, or at the facilitator’s location. With the advent of technology, they have also been held in virtual environments using same time, different place teleconferencing systems, but this approach poses its own challenges in maintaining the interpersonal nature of face-to-face discussions.

The client’s location offers the advantage of maximum exposure to the broadest number of in-house experts. Little time is lost due to travel, and personnel can be brought into the sessions on an as-needed basis. However, this colocation with the normal workplace can be a severe disadvantage. There is a strong tendency for key personnel to be distracted by phones, messages, and other business. Such interruptions can have a debilitating effect on the intensity of the session. Off-site locations help to avoid these distractions but have other limitations. They tend to be more costly, the number of participants is reduced, and critical facilities may be lacking (e.g., sufficient blackboard space and computer hookups). The facilitator’s location usually is the most efficient site. The number of participants may be limited (usually due to travel constraints), but the number of distractions is minimized and the facilitators can control more easily the flow of the agenda.

Decision conference facilities range from ordinary conference rooms to very sophisticated and specially designed facilities. White boards can be used with numerous colored markers to enhance visual displays, and computers are used to develop interactive decision models that can be projected onto large screens for all to see (Adelman, 1982). This arrangement allows the computer to be available for computational purposes, while, at the same time, being configured so as not to intimidate the participants (Ring, 1980). Coffee and other beverages can be available right in the conference rooms, and lunches are brought in at an appropriate time. Sessions typically last 8–10 hours, and participants often feel quite emotionally drained at the end of each day.

C.4 Use of Group Processes

Many of the inputs used to develop analytical models in the decision conference are elicited using well-documented group processes. Various methods are used to take advantage of the positive aspects of group behavior and to minimize the negative effects. These techniques can be categorized into three approaches: Delphi techniques, nominal group techniques, and consensus group techniques (Ulvila, 1984).

Delphi can be described as a mechanical method for controlling group processes. Each participant gives an individual opinion in an anonymous fashion, and is then shown all responses but not told who provided which response. Participants then revise opinions, and the assessment process goes through additional iterations. Delphi stresses anonymity, and works well to minimize the influence of strongly dominant personalities in the group. However, it is time consuming, and participants often lose interest after a few iterations (O’Connor, 1984).

Nominal group techniques call for all individuals to provide assessments to the group without discussion. Once these comments are made, and the contributors are identified, the group then discusses all judgments for clarification and evaluation. Individuals may reconsider their assessments at this point, and any remaining differences are resolved mathematically through averaging. The approach is appropriate for combative groups with wide variances in their sources of data (Ulvila, 1984).

Group consensus techniques involve open group discussions aimed at producing a consensus view. They stress face-to-face exchanges of information, and direct interactions are encouraged. They are most effective with cooperative groups, but skilled facilitators usually can overcome problems introduced by combative participants. The facilitator focuses discussion and keeps any individual from dominating the group. Most of the documented decision conferences have used group consensus techniques rather than the other approaches (Kramer & King, 1983).

From the perspectives of the authors, the “best practice” is to use consensus group techniques. While Delphi and nominal group process may be useful in preliminary discussions to get the group more quickly to a useful starting point for the consensus group process, we do not recommend Delphi or nominal group process as the primary technique for conducting decision conferences.

C.5 Advantages and Disadvantages

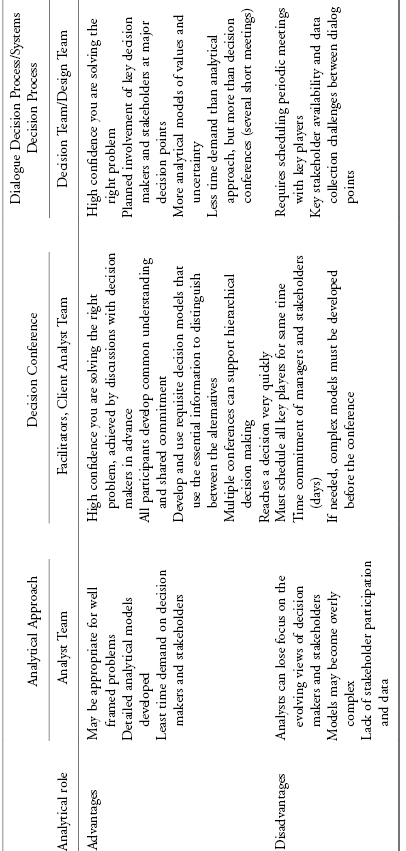

The decision conference approach offers several advantages when compared with less intensive, less structured methods, such as the dialogue decision process and other analytical approaches discussed in Chapter 5 (Table C.1).

TABLE C.1 Advantages and Disadvantages

In summary, the decision conference has the following positive features:

- The process is highly focused and productive; results that usually take weeks or months to achieve can be accomplished in a few days of concentrated effort.

- The process involves a broad base of technical expertise and management support throughout the organization; this widespread participation leads to greater commitment and more successful implementation.

- The approach specifically embodies and capitalizes on the substantive expertise of the client organization; the plan is produced with the client instead of for the client.

- Because everyone participates in a single directed discussion focused specifically on the decision at hand, communication among the participants is reliable and efficient; thorough documentation provides a permanent record of the conference proceedings and results, thus maintaining a reliable organizational memory of why certain decisions were made.

- The use of explicit computer-based decision analysis models helps the participants to understand and focus on the most critical issues, to debate those issues logically and clearly, and to apply their priorities consistently.

- The approach pays significant attention to the implementation of results; that attention ensures that the conclusions and recommendations are not only analytically sound, but also are directed toward immediate implementation.

- Finally, the approach ensures that participants have a vested interest in the decision they have analyzed; all participants are more likely to support the results if they have understood the approach and had a fair opportunity to present and debate their own viewpoints.

At the same time, the decision conference has the following limitations:

- It is sometimes difficult to get key personnel together for extended periods of time;

- The costs in terms of man-hours devoted to the decision conference can be high.

- Some people believe that there is too much reliance on expert subjective judgments and not enough on hard verifiable data.

- Facilitators are not experts in the substantive organizational matters, and may not understand the implications of the elicited judgments.

- If the wrong participants are selected for the conference, the results can turn out to be ineffective.

On balance, the decision conference is an innovation that enables managers to collaborate very efficiently and effectively to plan for and address difficult decisions. The product of a decision conference is a well-supported ”way ahead” for the client organization, backed by a thorough documentation of the key players’ collective analysis and judgments.

C.6 Best Practices

The following paragraphs comprise best practices as per the author’s experience:

- Face-to-face conferences (same-time, same place) work best. The ability to observe body language, gestures, eye rolling, and so on is very important, and often allows the facilitator to pick up on messages that might otherwise have been missed.

- Make use of consensus group techniques when facilitating. While Delphi and nominal group process may be useful in preliminary discussions to get the group more quickly to a useful starting point for the consensus group process, we do not recommend Delphi or nominal group process as the primary technique for conducting decision conferences.

- It should be noted that, although we talk about consensus often in this Handbook, disagreement is not only okay during deliberations, it is essential. A decision conference is not likely to succeed without it, and some of the more successful facilitators such as Cam Peterson and Roy Gulick,2 used this message to great advantage, even to the point of forcing disagreement when there appeared to be none. A basic truth is that we learn more when we disagree than when there is no dissent.

- Although most of the discussions and knowledge elicitation happens within the formal conference schedule itself, we should not underestimate the importance of lulls in the action, such as coffee breaks, nighttime social gatherings between working session days, breakouts, and so on. The author has found that inevitably, someone will want to talk during these “breaks,” and frequently, will bring to the fore some critical information that they were reluctant to raise in the formal group. Building these opportunities into the decision conference schedule is essential.

- While technology such as large-screen computer displays can be of great assistance to the process, they can also get in the way. Trying to take notes on a computer visible to the participants in real time can be a great distraction, and takes their attention away from the issue at hand. Computer displays typically allow for only one screen to be seen at a time. It is far more productive to make use of white boards, wall charts, and easel pads to ensure that all key pieces of information are visible at all times.

- We each must evolve our own style, often by watching and learning from what we like and do not like in other facilitators, from trying techniques that might or might not work, and by discovering what we feel comfortable doing. Facilitating decision conferences is far more of an art than a science.

- One of the most critical “rules” for the facilitator is to allow only one conversation at a time to allow everyone a fair opportunity to get their point across. That includes use of cell phones during the conference as well!

- One lesson that the author learned from Roy Gulick, is that to be successful, a decision conference facilitator has to be “45% decision analyst and 55% entertainer.” Being an entertainer means being enthusiastic, full of energy, exuding confidence that the session will succeed, engaging the “audience,” using facial expressions and gestures, and using tricks of the trade when necessary.

C.7 SUMMARY

Decision conferencing was introduced to move beyond the traditional “doctor–patient” model of consultancy by providing group processes that enable client stakeholders to plan for and analyze their decisions collaboratively. Decision conferencing brings together key people who know the issues surrounding a decision for an open exchange of information via dialogue and discussion, to provide relevant data and judgments, and to make decisions. Decision conferences are intensive collaborative working sessions, typically 1–3 days in length, that bring together decision makers, stakeholders, subject matter experts, and a team of trained facilitators for a “structured conversation” with the goal of informed consensus. A “best practice” for decision conference facilitators is to use group consensus processes rather than Delphi techniques or nominal group processes.

Decision conferences can be conducted at the client’s location, an off-site location, or at the facilitator’s location. Technology also provides the opportunity for decision conferencing in a virtual environment. The use of explicit computer-based decision analysis models helps the participants to understand and focus on the most critical issues, to debate those issues logically and clearly, and to apply their priorities consistently.

Decision conferences are highly focused and productive; involve a broad base of technical expertise and management support throughout the organization leading to greater commitment and more successful implementation; are produced with the client instead of for the client; and provide a thorough audit trail of rationale for the group judgments and decisions. At the same time, it is sometimes difficult to get key personnel together for extended periods of time; labor commitments can be high; and there sometimes can be too much reliance on expert subjective judgments and not enough on hard verifiable data.

KEY TERMS

Notes

1For evaluation, the most common software used includes HIVIEW, Logical Decisions, or Excel with add-ons. For resource allocation, the list includes Equity and Logical Decisions.

2Roy Gulick is a colleague and mentor of the author from days at Decisions and Designs, Inc., and is one of the most experienced decision conference facilitators in the world.

REFERENCES

Adelman, L. (1982). Real-time computer support for decision analysis in a group setting: Another class of decision support systems. ORSA/TIMS National Meeting, pp. 18–21. Detroit, MI: ORSA/TIMS.

IDCF (2012). Decision conferencing. http://decisionconferencingforum.org/node/2, accessed July 2012.

Kramer, K. & King, J. (1983). Computer Supported Conference Rooms. Irvine: University of California Press.

Kuskey, K. (1983). An Approach to Resource Allocation for Project Planning and Design. McLean, VA: Decisions and Designs, Inc.

Kuskey, K. (2004). Overview of Decision Facilitation. Vienna.

O’Connor, M.F. (1984). Methodology for corporate crisi decision making. In S. Andriole (ed.), Corporate Crisis Management. New York: Petrocelli Books.

Phillips, L. (2007). Decision conferencing. In W. Edwards, R. Miles, & D. von Winterfeldt (eds.), Advances in Decision Analysis, pp. 375–399. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Ring, R. (1980). A new way to make decisions. Graduate Engineer, November, 46–49.

Ulvila, J. (1984). Use of expert judgment. In T.A. Bresnick, J. Ulvila, D. Buede, R. Hullander, & R. Brown (eds.), Problem Solving and Decision Making: Workshop Manual. Falls Church, VA: Decision Science Consortium, Inc.