INTRODUCTION

This chapter considers the work of the business analyst following the initial problem investigation and the definition of requirements. Although utilised mainly during the early stages of the business change lifecycle, business analysis skills are also required through to the delivery of the solution, and beyond, in order to support and enable the successful implementation of the changes and the realisation of the benefits.

STAGES OF THE BUSINESS CHANGE LIFECYCLE

While business analysis is critical at the outset of a change project, there remains a lot of work to be done as the project progresses through the business change lifecycle. This may involve the engagement of stakeholders in order to ensure their continued buy-in, and the detailed design, development and deployment of the new processes and systems. To do this successfully requires a great deal of thought, preparation and planning – and all of these activities are facilitated by the involvement of business analysts.

There are five stages in the lifecycle introduced in Chapter 1 and reproduced in Figure 14.1. These stages represent the key areas of activity required to enable successful business change for an organisation.

Figure 14.1 The business change lifecycle (Reproduced by permission of Assist Knowledge Development Ltd)

- Alignment is concerned with ensuring the organisation’s objectives and strategy are aligned with the external business world, and that any proposed changes are aligned with the internal policies and architectures. This work is discussed in Chapter 3, including the involvement of the business analyst.

- Definition is concerned with taking a closer look at a proposed business situation in order to uncover root causes of problems, conduct a thorough analysis, recommend relevant, feasible changes and define the requirements. This stage is the topic of much of this book and is not explored further in this chapter. However, the business analysts will have defined the business and solution requirements by the conclusion of this stage.

- Design is concerned with the detailed specification, development and testing of the solution, including the business processes and related tasks, and the software that is needed to support them.

- Implementation is concerned with the planning and preparation for the deployment of the business changes.

- Realisation is concerned with the review of the predicted business benefits with a view to identifying those that have been achieved and taking further action to support the achievement of those still to be realised.

These stages are shown in the lifecycle as a sequence but this is not necessarily the case as there may be an iterative approach taken requiring some stages to be revisited. Therefore, it is preferable to consider the lifecycle as providing an overall direction for a change project rather than enforcing a straight sequence of activities.

BA ROLE IN THE BUSINESS CHANGE LIFECYCLE

Business analysis helps organisations implement change successfully so it follows that the role of the business analyst is relevant across the entire change lifecycle. The tools and techniques described throughout this book are invaluable when working within a change project. This is explored further below.

Design stage

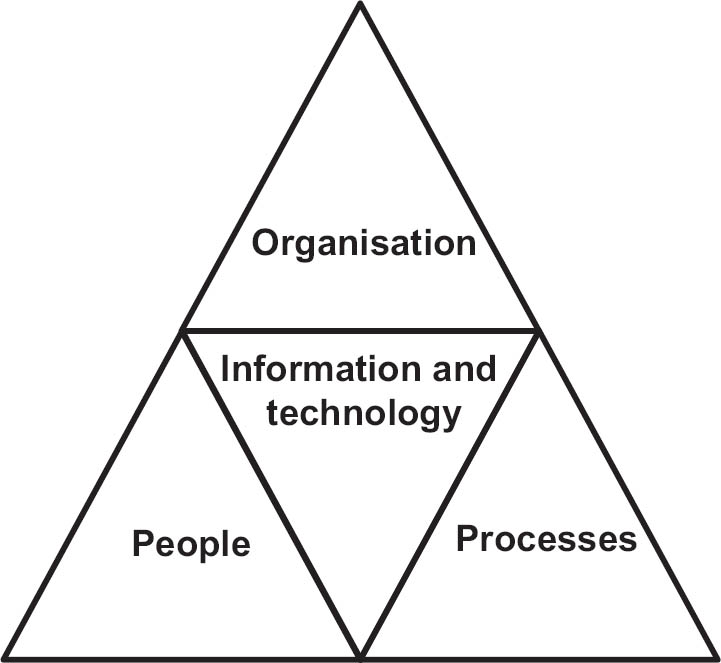

The design stage encompasses several major tasks: the design of the solution, and the development and testing of the software to support the solution. If the changes are complex, there may be a need for extensive testing or piloting of the revised business processes in order to ensure that they are robust and will deliver the required value. The POPIT™ model, shown in Figure 14.2, was introduced in Chapter 8 as a useful aid for gap analysis. However, it is also helpful to summarise the different elements to be addressed when designing a solution.

As can be seen in the POPIT model, there are four areas to be considered during the design stage: the organisation, the processes, the people and the information and technology. So, we cannot change the processes and systems without considering their impact upon the organisation’s management structure and job roles or upon the skill requirements of the staff. There may be a need to introduce a different structure because of the merger of teams. There may be a need to redefine jobs where the tasks conducted have changed. Different performance measures may be required. The capability of the teams may need to change in line with the new work practices. And all of this needs to be thought through, not only in terms of what the change might be but also how the change will be brought about.

Figure 14.2 The POPIT model (Reproduced by permission of Assist Knowledge Development Ltd)

People – skill development

If there needs to be new capability offered by the team, the skills of the team members will need to be identified and subject to a gap analysis. Having identified the required skills, the means of achieving them will need to be designed; this may involve the design and development of training events. Business analysts are often involved in capability uplift, delivering the training and support to business users to enable them to conduct their new work practices.

Organisation – structures, measures and jobs

Where the revised processes have involved the merger or change of the team structure this will need to be defined and the impact upon the management structure considered. The changes to business processes typically involve the introduction of amended, if not new, job roles, so these will also need to be defined. Again, the business analyst will be able to produce these definitions. There may also be a need to reconsider performance measures, such as CSFs and KPIs (see Chapter 3).

Business process design

The design of the ‘to be’ business processes was described in Chapter 7; this is a key area of business analysis work and is a fundamental part of the business change solution. However, there is a great deal of work to be done when a ‘to be’ process is to be implemented and it is often the case that this detail is overlooked or postponed. For example, there may be a need for detailed definition of the procedures and documentation to be used in the new process; or, the communication channels may need to be revised. All of this will need to be considered at an early stage in order to ensure that the solution is well understood and ready for deployment.

Chapter 13 set out the lifecycles used to develop the software required to support the business processes. While other chapters have discussed in detail the major aspects of business analysis work such as requirements definition and management, it is also worthwhile considering the BA role during the design, development and testing of the software solution.

Design

As the bridge between the business and the IT team, the business analyst is required to ensure that the requirements are understood and delivered. This may require them to clarify what the software needs to do. The requirements documentation provides the basis for the design of the software solution. Therefore, the business analyst may be required to support the design activity by clarifying any points, possibly following consultation with the business users.

Development

It may also be the case that the development team has detailed queries about the requirements, or that decisions about the detailed software functionality need to be made; the business analysts can help in communicating with the business staff and supporting them in making decisions about the detailed requirements. Given that the business analysts have an overall understanding of the solution, they can also be of great assistance during this discussion as they are able to assess the impact of proposals across the solution, identifying where there may be problems in adopting a particular approach and suggesting alternatives.

Testing

Business analysts regularly support user acceptance testing. Initially, the business analyst will have defined the acceptance criteria that will be used to confirm a requirement has been met. These will be defined in the requirements catalogue (see Chapter 11). Once the software has been developed and tested by the IT team, the business analysts may support the business staff during user acceptance testing. There are various techniques that may be used to define test cases and scenarios including:

- Use case descriptions – these support a use case diagram and show the system response to the occurrence of an event. A main success scenario or ‘happy day’ is documented as a series of steps plus any alternative scenarios that may occur.

- Decision tables – these set out clearly the range of conditions for a particular situation and the actions to be taken given a specific set of conditions. An example is shown in Figure 14.3.

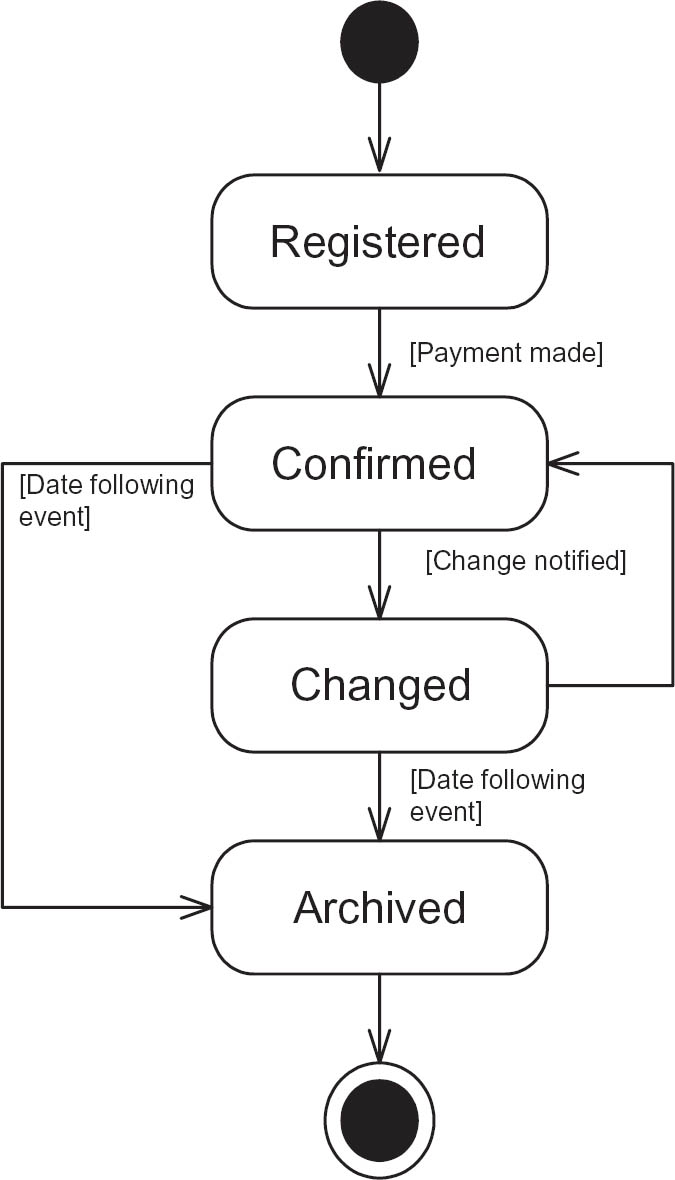

- State charts (also known as state transition diagrams and state machines) – these show the different states a particular entity or class may take on during its lifetime in the system. An example is shown in Figure 14.4.

Figure 14.3 Example decision table (Reproduced by permission of Assist Knowledge Development Ltd)

Figure 14.4 Example state chart (Reproduced by permission of Assist Knowledge Development Ltd)

The business analyst may also be involved in documenting the outcome of the user acceptance testing and, in some cases, considering how the issues that arise are to be addressed.

Implementation stage

The implementation of a business change programme requires a great deal of planning and any changes need to be executed with care. The major concern here is the emotional impact experienced by the business staff during this stage. A failure to consider this may inflame resistance and undermine the changes. In extreme cases, this may cause the entire change programme to fail. The SARAH model in Figure 14.5 sets out the emotional curve that may affect anyone experiencing the introduction of business change.

The SARAH model sets out five stages of the emotions experienced when someone is faced with a change.

Shock

The initial reaction to a change initiative is often shock. This may be due to a lack of awareness of the need for change. This may be particularly the case if most of the staff feel the organisation is doing well.

Anger

Shock then moves to anger as people begin to understand what the change may mean for them. This anger may be directed at the senior managers who have initiated the change and also at others – for example, the business analysts or developers – who are involved in bringing it about.

Rejection

When someone feels angry about the change, the next stage is to reject the ideas and direction. A sense of avoiding the change can develop along with the desire to be left to continue as normal.

Acceptance

Eventually an acceptance of the change develops. This may not mean that there is wholehearted support for the change but, as a minimum, a sense that the change is definitely happening so it is best to accept it.

Ultimately, people begin to see the positive benefits brought about by the change.

Business analysts must recognise that these reactions to change are to be expected in those affected by a business change programme. It is important that we are sensitive to these reactions and try to help people move through the different emotional stages. BAs can help support the business staff to cope with the business changes by providing coaching, training and ongoing support. They may also be able to offer reassurance to help the business staff gain confidence in using the new processes and systems. To do this requires a high degree of interpersonal and stakeholder engagement skill during the deployment of the changes.

Realisation stage

Benefits are only likely to be realised if they are defined well, planned for their delivery and managed properly. However, it is often the case with change projects that a lot of thought goes into planning the project to define, develop and deliver the solution but less into how the expected business benefits are to be achieved. It is vital that a comprehensive benefits plan is developed in addition to the business case so that the benefits can be tracked and managed.

The benefits plan

The benefits plan should include the following elements:

Context/vision

This sets out the background for the change project and provides a wider business context for the benefits.

Benefits profiles

This is a full description of each of the benefits, including the type of benefit and the identified benefit owner (see below). Each benefit profile includes information such as the identifier and name, the owner, any stakeholders involved or interested in the benefits, relevant measures and dependencies.

Benefits dependency network

The benefits dependency network shows the enabling and actual changes required to deliver the predicted business benefits. The dependencies between the benefits and the ultimate business objectives is also shown.

Responsibilities

A list of the benefit owners and their responsibilities.

Tracking procedures

How the benefits will be tracked and reported upon.

The benefit owner is a named individual who is tasked with ensuring that the benefit is achieved. To discharge this role effectively, the person nominated must be in a position to take the actions needed to secure the benefit, which implies that they are a senior manager with responsibility for the area in which the benefit will be gained. For instance, if the main benefit of a project is staff savings, then the benefit owner has to be someone in a position to make these savings. Sometimes – and particularly in large organisations – benefit ownership has to be shared among a number of people but this brings with it the problem of divided responsibility; some managers make the required changes to secure the benefits, others do not and so the project is less successful overall than it could have been.

Benefits dependency network

A benefits dependency network (or benefits map) is a diagrammatic representation of what needs to be done on a project in order to achieve its expected benefits. It also sets out how the benefits contribute towards the project’s ultimate (business) objectives. An example of such a framework – for an organisation that wishes to raise its public profile – is shown in Figure 14.6.

Figure 14.6 Benefits dependency network (adapted from Ward and Daniels (2012))

Although the arrows run from left to right, a benefits dependency network is best created right to left, starting with the overall business objectives that the change project is designed to achieve. We then work backwards to the set of benefits that will contribute to those objectives. Next, we consider what business changes will be required to secure those benefits. And finally we identify the enabling changes that will lead to the business changes.

The advantage of constructing a benefits dependency network such as that in Figure 14.6 is that it forces us to consider all of the work that is required to achieve the project’s business benefits, not just that related to IT systems development. As the example in Figure 14.6 shows, only one ‘stream’ of enabling/business changes represents the technical aspects of the project; the other ‘streams’ highlight the non-IT changes that will be required if the overall benefits and objectives are to be achieved.

The network also helps us to identify who should take responsibility for each stream. The technical stream, relating to the website redevelopment, for instance, is obviously the responsibility of the designated (IT) project manager whereas the stream relating to improved press coverage should probably be managed by the PR function or, if there isn’t one, by the marketing team.

Managing the business case

The business case needs to be managed throughout the business change lifecycle. The central and ongoing nature of the business case is shown clearly in Figure 14.1. Each time a request for change arises, it is important to review the business case to ensure that it is still valid and to reflect the impact of the change. There may be an effect upon several aspects of the business case, for example, the solution description, costs, benefits and risks. It is also usual to review the business case at key points during the business change lifecycle. This takes into account further detailed work that has taken place up to a particular stage and may also require changes to the costs, benefits and risks. If these changes are required the case for the investment must be checked to ensure continuing viability.

Benefits reviews

Management processes are needed to ensure that the benefits are reviewed in two circumstances:

Scheduled reviews

At each of the ‘decision gates’ in the project (see Figure 9.1 in Chapter 9), the expected benefits should be examined as part of the review. At each stage, careful consideration should be given to whether the expected benefits are still available and whether they are still sufficient to compensate for an increase in the expected costs of the project. In the light of such a review, it may be necessary to rework the financial case in order to define the expected investment return or even re-scope the project to improve the prospects of securing the maximum business benefit.

Unscheduled reviews

These should be triggered whenever a significant event occurs that could potentially affect the expected benefits. Major requests for change are an obvious example of such a situation as they could cause the project to cost more, take longer or deliver something different, and all of these might affect the benefits. Other significant events could include a change in the key stakeholders (especially the project sponsor), developments in the external business environment or a change to the organisation’s business strategy.

So, the business case should be reviewed frequently during the project in order to check if the predicted benefits are still able to be achieved and to identify any changes required to the project in order to enable those benefits to be delivered. The main evaluation, however, takes place after the project has finished and has been in operation for a designated period of time. Consideration should be given to the timescale required for the expected benefits to have materialised. Depending on the type and scale of the project, this could happen months, or even years, after the project ends. The evaluation will also examine the progress being made towards achieving the benefits and consider whether any further action needs to be taken to enable the benefits to be achieved.

Benefits Realisation Report

Ultimately a Benefits Realisation Report should be produced which assesses clearly whether the hoped-for benefits have been gained or not. This report has four important uses:

- Where the hoped-for benefits have not yet been achieved, to identify any additional actions that could be taken to retrieve them. For instance, if users are not making full use of a new system, additional training may be required.

- To reassure the decision-makers, and the wider organisation, that the time, effort and cost of the project has been justified.

- To provide input to future business cases and future projects, to help make them more successful.

- To enable the organisation, over time, to increase the capability for choosing which projects to undertake.

A benefits review is conducted at a designated point following the deployment of the business changes. The review focuses on the predicted benefits and assesses whether or not they have been realised. During the review, benefits that have not been fully realised should be analysed in order to identify where business changes have not taken place or where additional changes are needed. Where further changes are required to deliver the benefits, the benefits plan should be updated and a further benefits review should be scheduled. It is also possible that additional benefits are identified during the benefits review; these are benefits that were not predicted in the business case but may now be available as a result of the change project. The benefits review includes a consideration and analysis of what needs to be done to deliver these additional benefits. This will also result in changes to the benefits plan and scheduling of a further benefits review.

SUMMARY

This chapter has provided an insight into the contribution of the business analyst throughout the change lifecycle. It is often said that the implementation of change is the most difficult part to deliver successfully. In this book, we have looked at some of the key aspects of business analysis which should enable the identification, development and delivery of the right solutions for organisations. Business analysis is a discipline that can offer insights, proposals and recommendations grounded in real business needs and can help ensure wise investment of limited financial resources. It is important that organisations competing in today’s fast-moving business world recognise the role business analysts can play in helping ensure their success.

REFERENCE

Ward, J. and Daniel, E. (2012) Benefits Management: Delivering Value from IS and IT Investments. Wiley, Chichester.

FURTHER READING

Cadle, J., Paul, D. and Turner, P. (2014) Business Analysis Techniques: 99 essential tools for success, 2nd edn. BCS, Swindon.

Gambles, I. (2009) Making the Business Case. Gower Publishing, Farnham.