INTRODUCTION

This is a book about Business Analysis, a discipline that has evolved over the last two decades and has the potential to offer great benefit to organisations by ensuring that there is alignment between business needs and business change solutions. Many solutions involve the development of new or enhanced information systems but this is unlikely to be the extent of the business change, and it is probable that solutions will have a broader scope incorporating changes to areas such as business processes and job roles. The reason for producing this book is to provide guidance about business analysis that reflects the breadth of the role and the range of techniques used. While many organisations employ business analysts, there persists a lack of clarity about what the role really involves and this often creates more questions than answers. What do business analysts do? What skills do they require? How do they add value to organisations? Recognition in the broader business community is also an issue with many misconceptions regarding business analysis and a lack of appreciation of the contribution business analysts might make. Also, in the absence of a standard definition of business analysis and a standard set of business analysis activities, problems have arisen:

- Organisations have introduced business analysis to make sure that business needs are paramount when new IT systems are introduced. However, recognising the importance of this in principle is easier than ensuring that it is achieved. Many business analysts still report a drive towards documenting requirements without a clear understanding of the desired business outcomes.

- Some business analysts were previously experienced IT systems analysts and proved less comfortable considering the business requirements and the range of potential solutions that would meet the requirements.

- Many business analysts have a business background and have a limited understanding of IT and how software is developed. While knowledge of the business is invaluable for business analysts, problems can occur where IT forms part of the business solution and the analyst has insufficient understanding of IT. This may cause communication difficulties with the developers and could result in failure to ensure that there is an integrated view of the business and IT system.

- Some business analysts, as they have gained in experience and knowledge, have felt that they could offer beneficial advice to their organisations but a

lack of understanding of the role, and a focus on ensuring governance rather than understanding the need, has caused organisations to reject or ignore this advice.

This chapter examines business analysis as a specialist profession and considers how we might better define the business analyst role. In Chapter 4 we describe a process model for business analysis and an overview of two aspects: how business analysis is carried out and the key techniques to be used at each stage. Much of this book provides guidance on how the various stages in the business analysis process model may be carried out. Business analysis work is well defined where there are standard techniques that have been used in projects for many years. In fact, many of these techniques have been in use for far longer than the business analyst role has been in existence. We describe numerous techniques in this book that we feel should be within any business analyst’s toolkit, and place them within the overall process model. Our aim is to help business analysts carry out their work, improve the quality of business analysis within organisations and, as a result, help organisations to adopt business improvements that will ensure business success.

THE ORIGINS OF BUSINESS ANALYSIS

Developments in IT have enabled organisations to create information systems that have improved business operations and management decision-making. In the past, this has been the focus of IT departments. However, as business operations have changed, the emphasis has moved on to the development of new services and products. The questions we need to ask now are – ‘What can IT do to exploit business opportunities and enhance the portfolio of products and services?’ and ‘What needs to change in the organisation if the benefits from a new or enhanced IT system are to be realised?’

Technology has enabled new business models to be implemented through more flexible communication mechanisms that allow organisations to reach out to the customer, connect their systems with those of their suppliers and support global operations. The use of IT has also created opportunities for organisations to focus on their core processes and competencies without the distraction of the peripheral areas of business where they do not have specialist skills. These days, the absence of good information systems would prevent an organisation from developing significant competitive advantage and new organisations can gain considerable market share by investing in an IT architecture that supports service delivery and business growth. Yet for many years there has been a growing dissatisfaction in businesses with the support provided by IT. This has been accompanied by a recognition by senior management that IT investment often fails to deliver the required business benefit. In short, the technology enables the development of information systems but these rarely meet the requirements of the business or deliver the service that will bring competitive advantage to the organisation. The Financial Times (Mance 2013) reported that this situation applies to all sectors, with IT projects continuing to overrun their budgets by significant amounts and poor communication between business and technical experts remaining problematic. The perception that, all too frequently, information systems do not deliver the predicted benefits continues to be well founded.

THE DEVELOPMENT OF BUSINESS ANALYSIS

The impact of outsourcing

In a drive to reduce costs, and sometimes in recognition of a lack of IT expertise at senior management level, many organisations have outsourced their IT services rather than employ their own internal IT staff. They have handed much of this work to specialist IT service providers. This approach has been based upon the belief that specialist providers, often working in countries where costs are lower than the UK, will be able to deliver higher quality at lower cost. So, in organisations which have outsourced their IT function, the IT systems are designed, constructed and delivered using staff employed by an external supplier. This undoubtedly has advantages for both the organisation purchasing the services and the specialist supplier. The latter gains an additional customer and the opportunity to increase turnover and make profit from the contractual arrangement. The customer organisation is no longer concerned with all staffing, infrastructure and support issues and instead pays the specialist provider for delivery of the required service. In theory this approach has much to recommend it but, as is usually the case, the limitations begin to emerge once the arrangement has been implemented, particularly in the areas of supplier management and communication of requirements. The issues relating to supplier management are not the subject of this book, and would require a book in their own right. However, we are concerned with the issue of communication between the business and the outsourced development team. The communication and clarification of requirements is key to ensuring the success of any IT system development but an outsourcing arrangement often complicates the communication process, particularly where there is geographical distance between the developers and the business. We need to ask ourselves how well do the business and technical groups understand each other and is the communication sufficiently frequent and open? Communication breakdowns usually result in the delivered IT systems failing to provide the required level of support for the business.

The outsourcing business model has undoubtedly been a catalyst for the development of the business analysis function as more and more organisations recognise the importance of business representation during the development and implementation of IT systems.

Competitive advantage of using IT

A parallel development that has helped to increase the profile of business analysis and define the business analyst role, has been the growing recognition that three factors need to be present in order for the IT systems to deliver competitive advantage. First, the needs of the business must drive the development of the IT systems; second, the implementation of an IT system must be accompanied by the necessary business changes and third, the requirements for IT systems must be defined with rigour and accuracy. The traditional systems analyst role operated primarily in the last area; today’s business challenges require all three areas to be addressed.

Successful business change

During the last few years, organisations have adopted a broader view – from IT projects to business change programmes. Within these programmes, there has been recognition of the need for roles and skill sets that enable the successful delivery of business change initiatives. The roles of the programme manager and change manager are well defined, with a clear statement of their scope and focus within the business change lifecycle. However, we now need to ensure that the business analyst role – one that uncovers the root causes of problems, identifies the issues to be addressed and ensures any solution will align with business needs – has a similar level of definition and recognition. Figure 1.1 shows a typical business change lifecycle.

Figure 1.1 The business change lifecycle (Reproduced by permission of Assist Knowledge Development Ltd)

The early part of the business change lifecycle – Alignment and Definition – is concerned with the analysis of the organisation, its business needs and requirements in order to determine new ways of working that will improve the organisation’s efficiency and effectiveness. Later business change activities are concerned with change design and development, business acceptance testing and, post implementation, benefits review and realisation. Clearly, extensive analysis is required throughout the lifecycle if the changes are to be successful in order to deliver the desired benefits. The analysis work falls within the remit of business analysis yet, in many organisations, a coherent approach to business change, that includes business analysts in the business change lifecycle, is still awaited. As a result, it is often the case that the definition of the business needs and the requirements to ensure they are met are often unclear or not aligned. All too often the focus almost from the outset is on the solution rather than understanding what problem we are trying to address. The lack of clarity and alignment can result in the development or adoption of changes that fail to deliver business benefits and waste investment funds.

The importance of the business analyst

The delivery of predicted business benefits, promised from the implementation of IT, has proved to be extremely difficult, with the outsourcing of IT services serving to add complication to already complex situations. The potential exists for organisations to implement information systems that yield competitive advantage and yet this often appears to be just out of reach. Organisations also want help in finding potential solutions to business issues and opportunities, sometimes where IT may not prove to be the answer, but it has become apparent that this requires a new set of skills to support business managers in achieving this. These factors have led directly to the development of the business analyst role.

Having identified the relevance of the business analyst role, we now need to recognise the potential this can offer, particularly in a global economic environment where budgets are limited and waste of financial resources unacceptable. The importance of using investment funds wisely and delivering the business benefits predicted for business change initiatives, has become increasingly necessary to the survival of organisations.

Business analysts as internal consultants

Many organisations use external consultants to provide expert advice throughout the business change lifecycle. The reasons are clear – they can be employed to deal with a specific issue on an ‘as-needed basis’, they bring a broader business perspective and can provide a dispassionate, objective view of the company. On the other hand, the use of external consultants is often criticised, across all sectors, because of the lack of accountability and the absence of any transfer of skills from the external consultants to internal staff. Cost is also a key issue. Consultancy firms often charge daily fee rates that are considerably higher than the charge levied for an internal analyst and whilst the firms may provide consultants with a broad range of expertise steeped in best practice, this is not always guaranteed. The experiences gained from using external consultants have also played a part in the development of the internal business analysis role. Many business analysts have argued that they can provide the services offered by external consultants and can, in effect, operate as internal consultants. Reasons for using internal business analysts as consultants, apart from lower costs, include speed (internal consultants do not have to spend time learning about the organisation) and the retention of knowledge within the organisation. These factors have been recognised as particularly important for projects where the objectives concern the achievement of business benefit through the use of IT and where IT is a prime enabler of business change. As a result, while external consultants are used for many business purposes, the majority of business analysts are employed by their organisations. These analysts may lack an external viewpoint but they are knowledgeable about the business domain and crucially will have to live with the impact of the actions they recommend. Consequently, there have been increasing numbers of business analysts working as internal consultants over the last decade.

THE SCOPE OF BUSINESS ANALYSIS WORK

A major issue for business analysts is the definition of the business analyst role. Discussions with several hundred business analysts, across a range of business forums, have established that business analysis roles do not always accurately represent the range of responsibilities that business analysts are capable of fulfilling.

The range of analysis activities

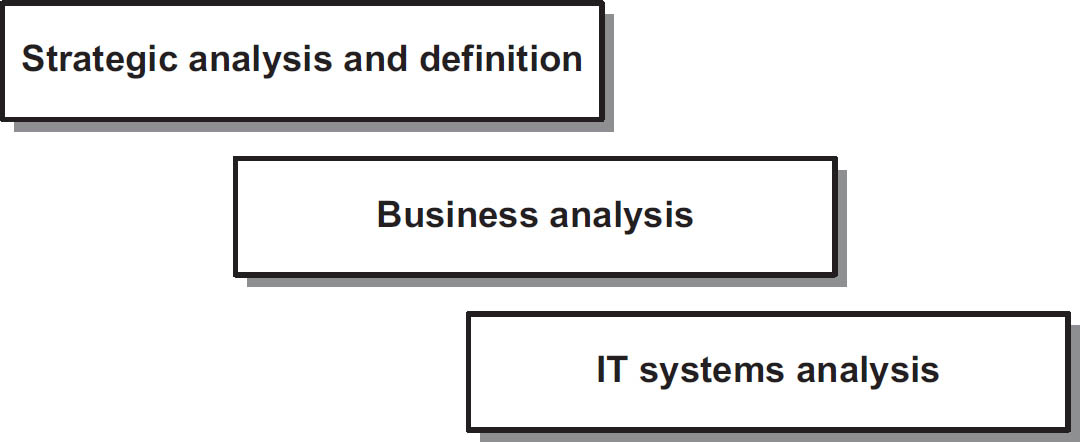

One way in which we can consider the business analyst role is to examine the potential extent of analysis work. Figure 1.2 shows three areas that we might consider to be within the province of the business analyst. There are always unclear aspects where the three areas overlap. For example, consultants may specialise in strategic analysis but also get involved in business process redesign to make a reality of their strategies, and good systems analysts have always understood the need to understand the overall business context of the systems they are developing. However, it is useful to examine them separately in order to consider their relevance to the business analyst role.

Figure 1.2 The potential range of the business analyst role (Reproduced by permission of Assist Knowledge Development Ltd)

Strategic analysis and definition

Strategic analysis and definition is typically the work of senior management, often supported by strategy consultants. Some business analysts may be required to undertake strategic analysis and identify business transformation actions, but it is more likely that they will have a role to play in supporting this activity. In the main, we believe that strategic analysis is mostly outside the remit of business analysis. We would, however, expect business analysts to have access to information about their organisation’s business strategy and be able to understand it, as their work will need to support the execution of this strategy. Business analysts often have to recommend and design the tactics that will deliver the business objectives and strategy, typically the process and IT system solutions. Hence, it is vital that they are able to work within the strategic business context. It may also be the case that some business analyst roles will require strategic level thinking. The use of IT to enable business improvements and the opportunities presented by technology will need to be considered during any strategy analysis and the business analysts are the specialist team that should be able to advise on the use of technology to drive business change. Given these issues, we feel that, while strategic analysis work is not core to business analysis, business analysts will need a good understanding of how strategy is developed and the impact upon the work of the IT and business change functions. In view of this, Chapter 3 explores a range of strategic analysis techniques and provides an overview of the strategic planning process.

IT systems analysis

At the other end of our model, there is the traditional IT discipline called systems analysis. The systems analyst role has been in existence for over 40 years although the term ‘systems analyst’ tends to be used less often these days. Systems analysts are responsible for analysing and specifying the IT system requirements in sufficient detail to provide a basis for the evaluation of software packages or the development of a bespoke IT system. Typically, systems analysis work involves the use of techniques such as data modelling and process or function modelling. This work is focused on describing the software requirements, and so the products of systems analysis define exactly what data the IT system will record, the processing that will be applied to that data and how the user interface will operate. Some organisations consider this work to be of such a technical nature that they perceive it to be completely outside the province of the business analyst. They have identified that modelling process and data requirements for the IT system is not part of the role of the business analyst and have separated the business analysis and IT teams into different departments, expecting the IT department to carry out the detailed IT systems modelling and specification. Other organisations differentiate between IT business analysts and ‘business’ business analysts, with those in IT often performing a role more akin to that of a systems analyst. In order to do this, the business analysts need a detailed understanding of IT systems and how they operate, and must be able to use the approaches and modelling techniques that fell historically within the remit of the system analyst role. The essential difference here is that a business analyst is responsible for considering a range of business options to address a particular problem or opportunity; on the other hand an IT business analyst, or systems analyst, works within a defined scope and considers options for the IT solution. In some organisations, there is little divide between the business analysts and the IT team. In these cases the business analysts work closely with the IT developers and include the definition of IT system requirements as a key part of their role. This is particularly the case where an Agile approach has been adopted for a software development project; the business analyst will work closely with the end users and development team to clarify the detailed requirements as they evolve during the development process.

Business analysis

If the two analysis disciplines described above define the limits of analysis work, the gap in the middle is straddled by business analysis. This is reflected in Figure 1.2 which highlights the potential scope and extent of business analysis work. Business analysts will usually be required to investigate a business system where improvements are required but the range and focus of those improvements can vary considerably.

- It may be that the analysts are asked to resolve a localised business issue. In such a case, they would need to recommend actions that would overcome a problem or achieve business benefits.

- Perhaps it is more likely that the study is broader than this and requires investigation into several issues, or perhaps ideas, regarding increased efficiency or effectiveness. This work would necessitate extensive and detailed analysis of the business area. The analysts would need to make recommendations for business changes and these would need to be supported by a rigorous business case.

- Another possibility is that the business analyst is asked to focus specifically on enhancing or replacing an existing IT system in line with business requirements. In this case the analyst would deliver a requirements document defining what the business requires the IT system to provide. This document may define the requirements in detail or may be at a more overview level, depending upon the approach to the system development. Where an Agile approach is to be used, the business analyst may also be involved in prioritising the requirements and identifying those to be input into the next development iteration.

- More senior business analysts may be involved in working cross-functionally, taking a value delivery approach. This work is likely to require analysis of a workstream comprising various activities and systems. In this case, the analyst will need to have wide-ranging skills not only in analysis but also in stakeholder relationship management, and they will also require extensive business domain knowledge.

Whichever situation applies, the study usually begins with the analyst gaining an understanding of the business situation in hand. A problem may have been defined in very specific terms, and a possible solution identified, but in practice it is rare that this turns out to be the entire problem and it is even less the case that any proposed solution addresses all of the issues. More commonly, there is a more general set of problems that require a broad focus and in-depth investigation. Sometimes, the first step is to clarify the problem to be solved as, without this, any analysis could be examining the wrong area and, as a result, identifying unhelpful solutions. For any changes to succeed the business analyst needs to consider all aspects, for example, what processes, IT systems, job roles, skills and other resources will be needed to improve the situation. In such situations, techniques such as stakeholder analysis, business process modelling and requirements engineering may all be required in order to identify the actions required to improve the business system. These three topics are the subject of later chapters in this book.

Realising business benefits

Analysing business situations, and identifying areas for business improvement, is only part of the process; the analyst may also be required to help develop a business case in order to justify the required level of investment and ensure any risks are considered. One of the key elements of the business case will be the identification and, where relevant, the quantification of the business benefits. Organisations are placing increasing emphasis upon ensuring that there is a rigorous business case to justify the expenditure on business improvement projects. However, defining the business case is only part of the picture – the focus on the management and realisation of these business benefits, once the solution has been delivered, is also growing. This is largely because organisations have limited funds for investment and need to ensure that they are spent wisely. There has been a long history of failure to assess whether or not business benefits have been realised from change projects but this is becoming increasingly unacceptable as the financial pressures mount on organisations and the calls for transparency grow. The business analyst will not be the only role involved in this work. However, ensuring that changes are assessed in terms of the impact upon the business case and, at a later point, supporting the assessment of whether or not predicted business benefits have been realised, is a key element of the role.

Taking a holistic approach

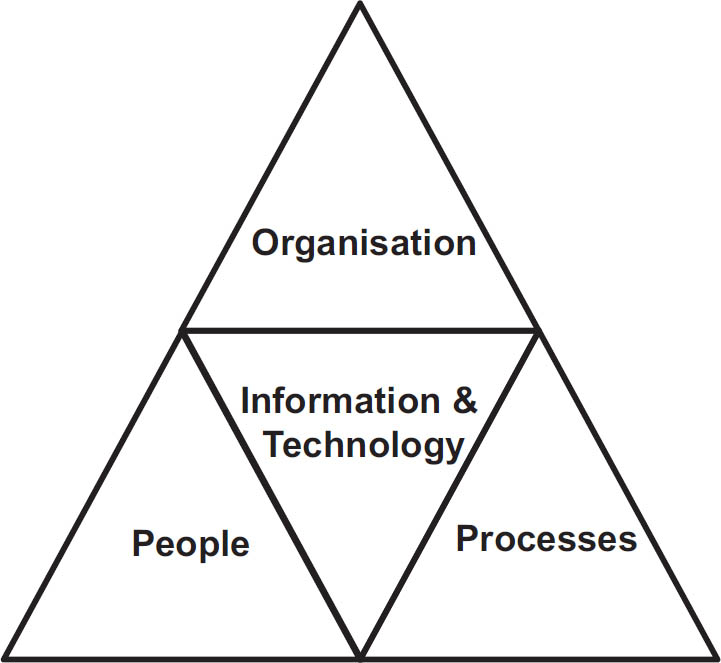

There appears to be universal agreement that business analysis requires the application of a holistic approach. Although the business analyst performs a key role in supporting management’s exploitation of IT to obtain business benefit, this has to be within the context of the entire business system. Hence, all aspects of the operational business system need to be analysed if all of the opportunities for business improvement are to be uncovered. The POPIT model in Figure 1.3 shows the different views that must be considered when identifying areas for improving the business system.

Figure 1.3 The POPIT model showing the views of a business system (Reproduced by permission of Assist Knowledge Development Ltd)

This model shows us the different aspects, and the correspondences between them, that business analysts need to consider when analysing a business system. For each area, we might consider the following:

- The processes – are they well defined and communicated? Is there good IT support or are there several ‘work-arounds’ in existence? Does the process require documents to be passed around the organisation unnecessarily? Is there the potential for delays or the introduction of errors?

- The people – do they have the required skills for the job? How motivated are they? Do they understand the business objectives that they need to support?

- The organisation – is there a supportive management style? Are jobs and responsibilities well defined? Is there collaborative cross-functional working?

- The information – do the staff have the information to conduct their work effectively? Are managers able to make decisions based on accurate and timely information?

- The technology – do the systems support the business as required? Do they provide the information needed to run the organisation?

We need to examine and understand all of these areas to uncover where problems lie and what improvements might be possible, if the business system is to become more effective. Taking a holistic view is vital as this ensures not only that all of the aspects are considered but also the linkages between them. It is often the case that the focus of a business analysis or business change study is primarily on the processes and the IT support. However, even if we have the most efficient processes with high standards of IT support, problems will persist if issues with staffing, such as skills shortages, or the organisation, such as management style, have not also been addressed.

It is vital that the business analyst is aware of the broader aspects relating to business situations such as the culture of the organisation and its impact on the people and the working practices. The adoption of a holistic approach will help ensure that these aspects are included in the analysis of the situation.

Business analysis places an emphasis on improving the operation of the entire business system. This means that, while technology is viewed as a factor that could enable improvements to the business operations, other possibilities are also considered. The focus should be on business improvement, rather than on the use of automation per se, resulting in recommendations that improve the business. Typically, these include the use of IT but this is not necessarily the case. There may be situations where a short-term non-IT solution is both helpful and cost-effective. For example, a problem may be overcome by developing internal standards or training members of staff. These solutions may be superseded by longer term, possibly more costly, solutions, but the focus on the business has ensured that the immediate needs have been met. Once urgent issues have been addressed, the longer term solutions can be considered more thoroughly. It is important that our focus as business analysts is on identifying opportunities for improvement with regard to the needs of the particular situation. If we do this, we can recommend changes that will help deliver real business improvements and ensure that funds are invested prudently.

Agile systems development

Agile is a software development approach which emerged in the late 1990s in the wake of approaches such as Rapid Application Development (RAD) and the Dynamic System Development Method (DSDM). The use of such approaches evolved as a reaction to the linear waterfall lifecycle, with its emphasis on completing a stage before moving on to the next stage. The Agile philosophy is to deliver software increments early and to elaborate requirements using approaches such as prototyping. The Agile Manifesto stated:

We are uncovering better ways of developing software by doing it and helping others do it. Through this work we have come to value:

Individuals and interactions over processes and tools

Working software over comprehensive documentation

Customer collaboration over contract negotiation

Responding to change over following a plan

That is, while there is value in the items on the right, we value the items on the left more.

So, what does this mean for the business analyst? In essence, where a business analyst is working on a project where an Agile software development approach has been adopted, the analyst will be involved in supporting the business users in clarifying, elaborating and prioritising the requirements during the development process. While some early business analysis work will have been required to uncover the problems to be addressed and define the business requirements, at a solution level the more detailed requirements will be elaborated during timeboxed iterations where collaborative teams comprising users, analysts and developers work together to develop part of the software required product. The business analyst brings domain expertise and analytical ability to the development team, assisting the users by assessing the impact of proposed functionality in the light of the strategic business context. The role of the business analyst in an Agile environment is explored further in Chapters 10 and 13.

Supporting business change

It is often commented that, even when the business analysts have defined excellent solutions that have been well-designed and developed, business improvement initiatives can fail during implementation. The business analyst may be required to support the implementation of the business changes. Figure 1.3 also offers an effective structure for identifying the range of areas to be considered. One aspect may concern the business acceptance testing – a vital element if business changes are to be implemented smoothly. The business analyst’s involvement in business acceptance testing can include work such as developing test scenarios and working with the business users as they apply the scenarios to their new processes and systems. Further, the implementation of business change may require extensive support from the business analysts, including tasks such as:

- writing procedure manuals and user guides;

- training business staff in the use of the new processes and IT systems;

- defining job roles and writing job role descriptions;

- providing ongoing support as the business staff begin to adopt the new, unfamiliar, approaches.

The role of the business analyst throughout the change lifecycle is explored further in Chapter 14.

THE ROLE AND RESPONSIBILITIES OF A BUSINESS ANALYST

So where does this leave us in defining the role and responsibilities of a business analyst? Although there are different role definitions, depending upon the organisation, there does seem to be an area of common ground where most business analysts work. These core responsibilities are:

- Investigate business systems taking a holistic view of the situation; this may include examining elements of the organisation structures and staff development issues as well as current processes and IT systems.

- Evaluate actions to improve the operation of a business system. Again, this may require an examination of organisational structure and staff development needs, to ensure that they are in line with any proposed process redesign and IT system development.

- Document the business requirements for the IT system support using appropriate documentation standards.

- Elaborate requirements, in support of the business users, during evolutionary system development.

In line with this, we believe the core business analyst role should be defined as:

An advisory role which has the responsibility for investigating and analysing business situations, identifying and evaluating options for improving business systems, elaborating and defining requirements, and ensuring the effective implementation and use of information systems in line with the needs of the business.

Some business analysis roles extend into other areas, possibly the strategic analysis or systems analysis activities described above. This may be where business analysts are in a more senior role or choose to specialise. These areas are:

- Strategy implementation – here the business analysts work closely with senior management to help define the most effective business system to implement elements of the business strategy.

- Business case production – more senior business analysts usually do this, typically with assistance from Finance specialists.

- Benefits realisation – the business analysts carry out post-implementation reviews, examine the benefits defined in the business case and evaluate whether or not the benefits have been achieved. Actions to achieve the business benefits are also identified and sometimes carried out by the business analysts.

- Specification of IT requirements – typically using standard modelling techniques such as data modelling or use case modelling.

The definition of the business analyst role may be expanded by considering the rationale for business analysis. The rationale seeks to explain why business analysis is so important for organisations in today’s business world and imposes responsibilities that business analysts must recognise and accept.

The rationale for business analysis is:

- Root causes not symptoms

- To distinguish between the symptoms of problems and the root causes

- To investigate and address the root causes of business problems

- To consider the holistic view

- Business improvement not IT change

- To recognise that IT systems should enable business opportunity or problem resolution

- To analyse opportunities for business improvement

- To enable business agility

- Options not solutions

- To challenge pre-determined solutions

- To identify and evaluate options for meeting business needs

- Feasible, contributing requirements not meeting all requests

- To be aware of financial and timescale constraints

- To identify requirements that are not feasible and do not contribute to business objectives

- To evaluate stated requirements against business needs and constraints

- The entire business change lifecycle not just requirements definition

- To analyse business situations

- To support the effective development, testing, deployment and post-implementation review of solutions

- To support the management and realisation of business benefits

- Negotiation not avoidance

- To recognise conflicting stakeholder views and requirements

- To negotiate conflicts between stakeholders

THE BUSINESS ANALYSIS MATURITY MODEL

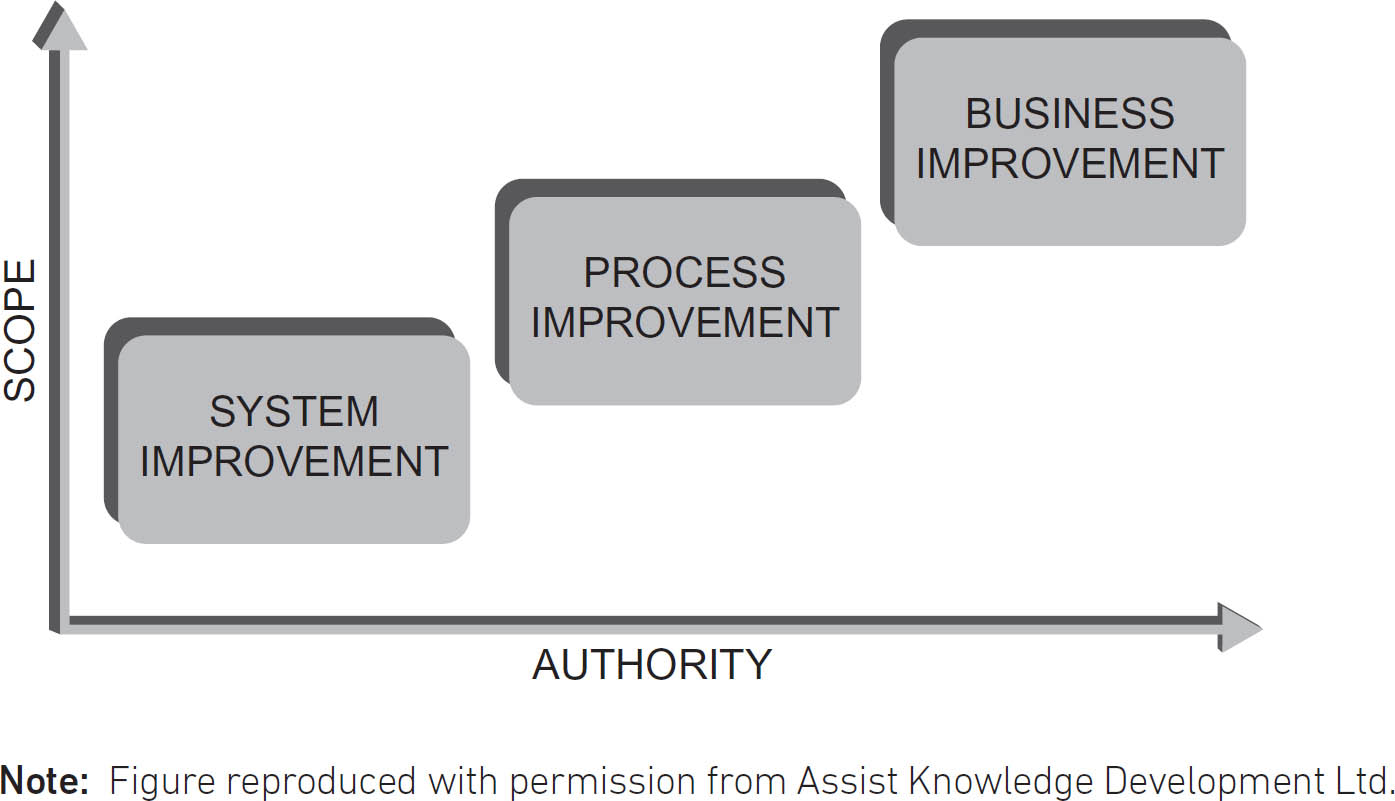

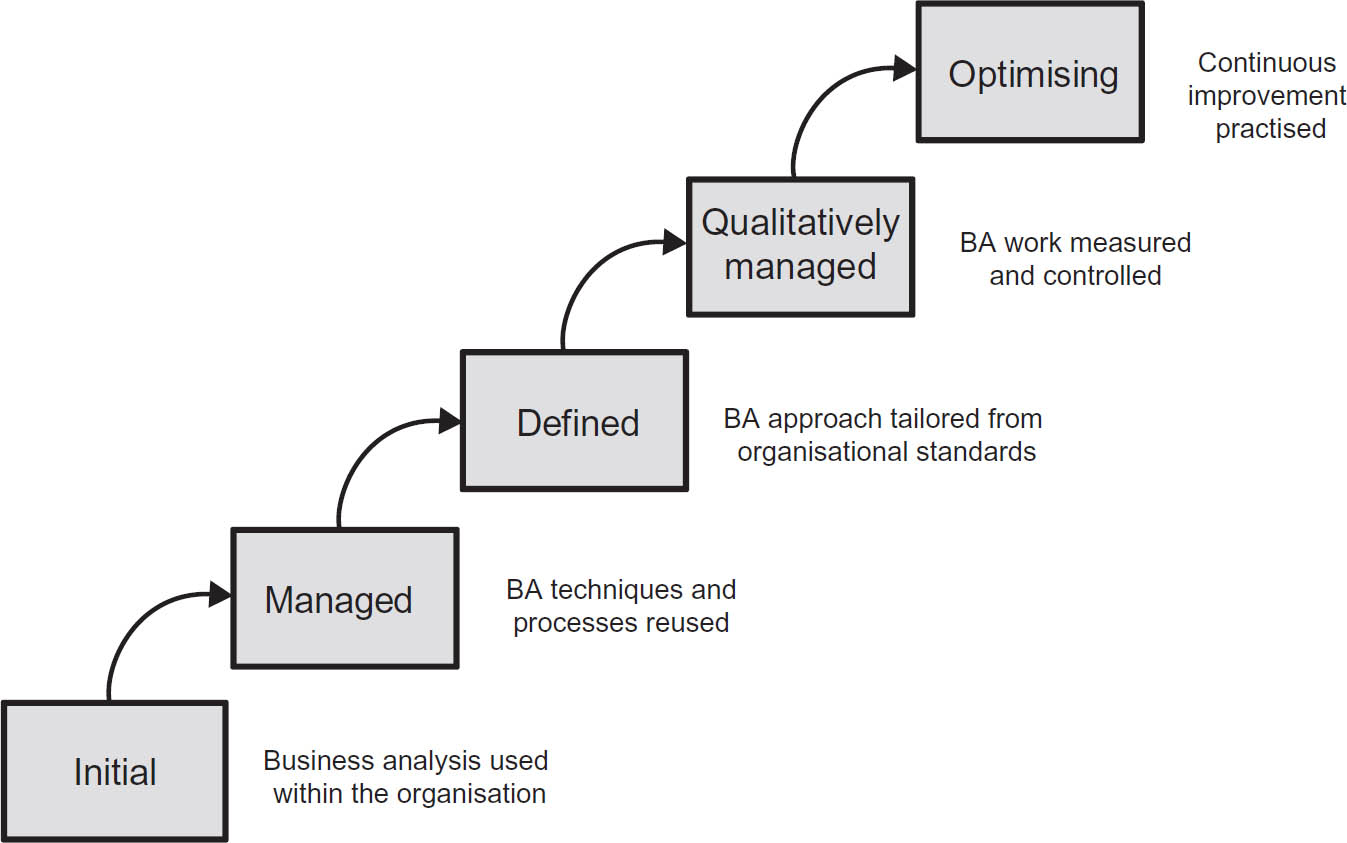

As the Business Analysis Practice has developed within organisations, a progression for business analysis itself has emerged reflecting this development. The Business Analysis Maturity Model™ (BAMM) shown in Figure 1.4 was developed by Assist Knowledge Development Ltd to represent the development and maturity of business analysis.

Figure 1.4 The Business Analysis Maturity Model™ (Reproduced by permission of Assist Knowledge Development Ltd)

This model reflects discussions with several hundred, if not thousands, of business analysts working for numerous organisations across the UK, Europe and beyond. These business analysts have come from different backgrounds – some from IT, many from business areas – and have brought different skills and knowledge to their business analysis teams. The BAMM uses two axes: the scope of the work allocated to the business analyst and the authority level of the business analyst. The scope may be very specific if an initial study has identified the required course of action and the analyst now needs to explore and define solution in greater detail. Alternatively, the scope may have been defined at only an overview level, or may be very ambiguous, with the business analyst having to carry out detailed investigation to uncover the issues before the options can be explored. The level of authority of the business analyst can also vary considerably, from a limited level of authority to the ability to influence and guide at senior management level.

The BAMM shows three levels of maturity during the development of business analysis. The first level is where the business analysis work is concerned with defining the requirements for an IT system improvement. At this level, the scope is likely to be well-defined and the level of authority limited to the project on which the business analyst works. The next level is where the business analysis work has moved beyond a specific IT development so that the analysts work cross-functionally to improve the business processes that give rise to the requirements. The third level is where the scope and authority of the analysts are at their greatest. Here, the business analysis work is concerned with improving the business and working with senior management to support the delivery of value to customers.

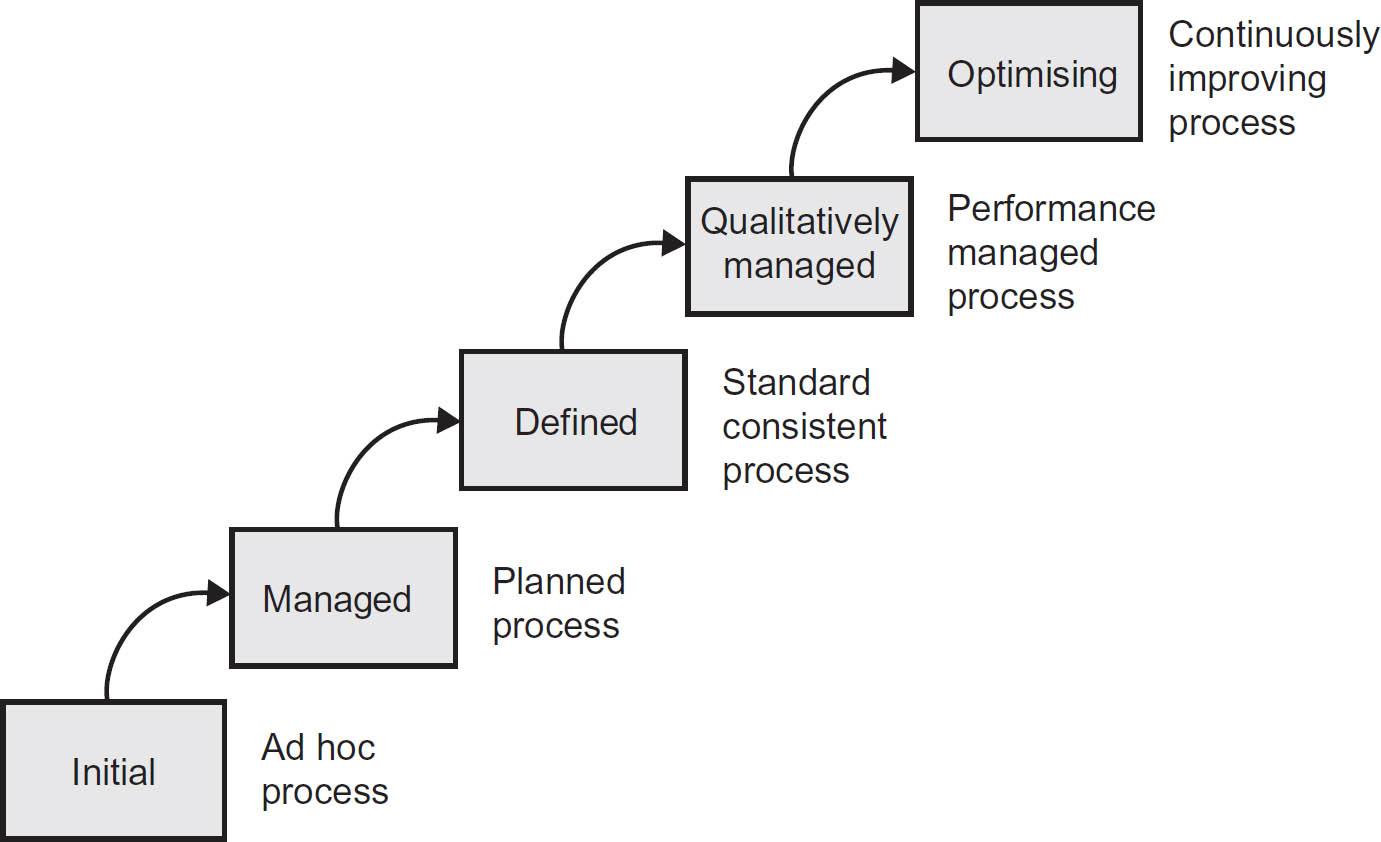

These levels of maturity apply to three perspectives on business analysis: the individual analysts, the business analysis community within an organisation, and the business analysis profession as a whole. At each level, the application of techniques and skills, the use of standards, and the evaluation of the work through measures, can vary considerably. One of the points often raised about the BAMM is the link to the Capability Maturity Model Integration (CMMI) represented in Figure 1.5. The CMMI was developed by the Software Engineering Institute (SEI) at Carnegie Mellon University and is an approach used for process improvement in organisations. If we consider the BAMM in the light of the CMMI, we can see that the five levels of the CMMI apply at each level.

Figure 1.5 The Capability Maturity Model Integration

An organisation that is developing its Business Analysis Practice may employ business analysts who are chiefly employed on requirements definition work. In doing this, the analysts may initially have to develop their own process and standards for each piece of work. Therefore, they would be at the Systems Improvement level of the BAMM and the Initial level of the CMMI. By contrast, an organisation that has employed business analysts for some time may have analysts that can work at all three levels of the BAMM. The analysts working at the Business Improvement level may have a defined process, standards and measures that are managed for each assignment. These business analysts are working at the Managed level of the CMMI.

It is also useful to consider a version of CMMI, specifically developed to evaluate the maturity of the Business Analysis Practice. Figure 1.6 shows a possible approach to this maturity assessment.

Figure 1.6 CMMI for business analysis (Reproduced by permission of Assist Knowledge Development Ltd)

PROFESSIONALISM AND BUSINESS ANALYSIS

Business analysis has developed a great deal over the last 25 years, to the extent that it is often referred to as a ‘profession’ and many practitioners view themselves as having a career in business analysis. The factors that support professionalism in business analysis are as follows:

- Qualifications – qualifications that determine the standard of skills and abilities of the individual professional that are recognised by employing organisations. Many business analysts hold qualifications such as the BCS International Diploma in Business Analysis or the IIBA® CBAP® or CCBA® certifications. The seniority of some business analysts has also been recognised by the introduction of the Expert BA Award offered by the BA Manager Forum. It is increasingly the case that organisations require business analysts to hold qualifications.

- Standards – techniques and documentation standards that are applied in order to carry out the work of the profession. Organisations typically have templates for documents and standardise on modelling techniques such as those provided by the Unified Modeling Language. Books such as this one are also used in many organisations as a foundation for standards of business analysis practice.

- Continuing Professional Development – recognition of the need for the continuing development of skills and knowledge in order to retain the professional status.

- Professional Body – a body with responsibility for defining technical standards and the code of conduct, promoting the profession and carrying out remedial action where necessary. This may require the removal of members where they do not reach the standard required by the code of conduct. The major professional bodies for business analysts are BCS, the Chartered Institute for IT and IIBA.

We have come a long way in twenty-five years. Gradually, the business analyst role is being defined with increasing clarity, individuals with extensive expertise are developing and enhancing their skills, best practice is gaining penetration across organisations, and a business analysis profession is becoming established.

THE FUTURE OF BUSINESS ANALYSIS

Business analysis has developed into a specialist discipline that can offer significant value to organisations, not least by assuring the delivery of business benefits and preventing unwise investments in ill-conceived solutions. Business analysis offers an opportunity for organisations to ensure not only that technology is deployed effectively to support the work of the organisation, but also that relevant options for business change are identified that take account of budgetary and timescale pressures. Business analysts can offer objective views that can challenge conventional wisdom, uncover root causes of problems and define the changes that will accrue real business benefits. Business analysts are passionate about their work and the contribution they can make. They continually develop their skills and extend the breadth of work they can undertake. Not only are they able to bridge IT and ‘the business’ but they can also offer guidance on how to approach business change work and where priorities might lie. Where outsourcing initiatives operate across departmental boundaries and sometimes have impacts upon the entire organisation, the work carried out by business analysts is vital if the new part in-house, part outsourced processes and technology are going to deliver value to customers. The challenge for the analysts is to ensure that they develop the extensive toolkit of skills, behavioural, business and technical, that will enable them to engage with the problems and issues facing their organisations, and assist in their resolution. The challenge for the organisations is to support the analysts in their personal development, recognise the important contribution they offer, ensure they have the authority to carry out business analysis to the extent required by the situations they face, and listen to their advice. This book has been developed primarily for the business analysis community but it is also intended to help business professionals face the challenges of today’s business environment; we hope anyone involved in defining and delivering business change will find it useful.

REFERENCE

Mance, H. (2013) ‘Why big IT projects crash’, Financial Times, 18 September, available online at http://www.ft.com/cms/s/2/794bbb56-1f8e-11e3-8861-00144feab7de.html#axzz2jL208Sjj [accessed 18 June 2014].

FURTHER READING

Cadle, J. (ed.) (2014) Developing Information Systems. BCS, Swindon.

Cadle, J., Paul, D. and Turner, P. (2014) Business Analysis Techniques: 99 essential tools for success, 2nd edn. BCS, Swindon.

Harmon, P. (2007) Business Process Change, 2nd edn. Morgan Kaufmann, Burlington, MA.

IIBA (2014) Business Analysis Body of Knowledge (BABOK), IIBA, available at www.theiiba.org [accessed 18 June 2014].

Johnson, G., Scholes, K. and Whittington, R. (2008) Exploring Corporate Strategy, 8th edn. FT Prentice Hall, Harlow.

Senge, P. M. (2006) The Fifth Discipline: The Art and Practice of the Learning Organisation, 2nd edn. Random House Books, London.