INTRODUCTION

Effective stakeholder management is absolutely crucial to the success of any business analysis project. Knowing who the stakeholders are, and understanding what it is they expect from the project and delivered solution, is vital if they are to remain involved and supportive of the undertaking. One of the major reasons why business analysis projects do not succeed – or do not succeed fully – is poor stakeholder management. The project team does not recognise the importance, or even the existence, of a key stakeholder and they find that their plans are constantly frustrated. On the other hand, if the right stakeholders are identified and managed properly, most obstacles can be cleared from the path. In fact, much of the groundwork for stakeholder management takes place before the business analysis project proper begins – during project inception and initiation – and that work must be revisited constantly during the project itself. The basic steps involved are illustrated in Figure 6.1.

Figure 6.1 Stakeholder management in the project lifecycle (Reproduced by permission of Assist Knowledge Development Ltd)

The main responsibility for stakeholder management may rest with the project manager or with a senior business analyst. However, all team members have important roles to play, in identifying stakeholders, in helping to understand their needs and by helping to manage their expectations of the project.

STAKEHOLDER CATEGORIES AND IDENTIFICATION

As Figure 6.1 illustrates, the first step in stakeholder management involves finding out who the stakeholders are. A good working definition of a stakeholder is ‘anyone who has an interest in, or may be affected by, the issue under consideration’. This means, more or less, anyone affected by the project or who may be in a position to influence it.

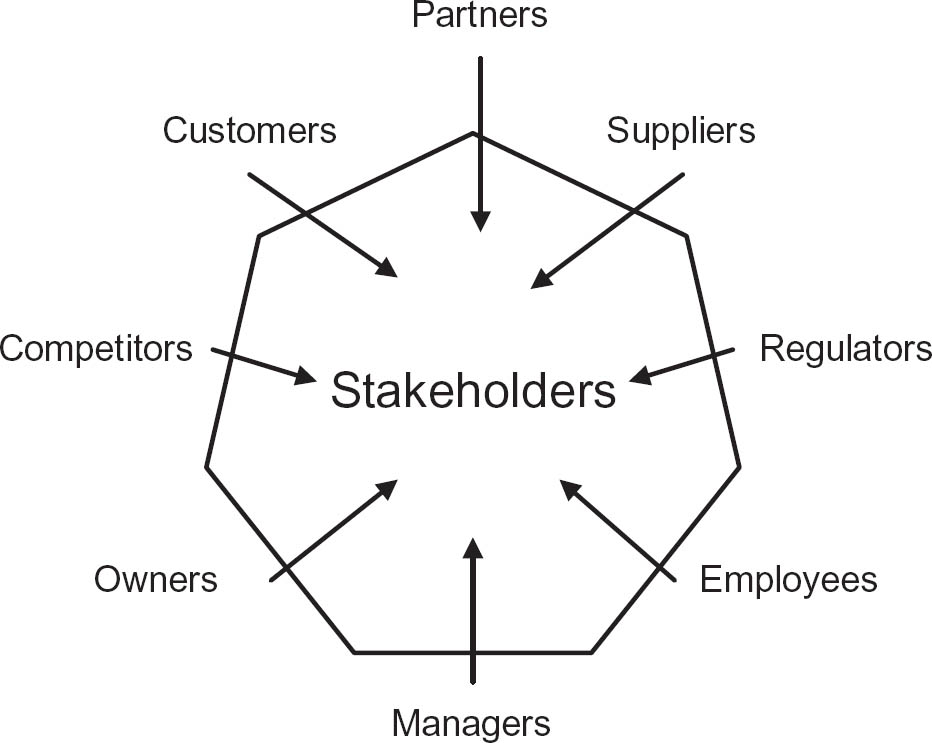

Of course, each project will have its own distinctive set of stakeholders, determined by the nature of the project and the environment in which it is taking place. However, we can identify some ‘generic’ stakeholder categories that may apply to many projects, as illustrated in Figure 6.2.

Figure 6.2 The stakeholder wheel (Reproduced by permission of Assist Knowledge Development Ltd)

Customers

These are the people or organisations for whom our organisation provides products or services. They are stakeholders because anything we do in the way of change has a potential effect on them. We must consider how to manage that change most effectively so as not to lose customers that we wish to retain. It may be useful to subdivide this general category to reveal more detail about the stakeholders, for example into:

- large or small;

- regular or occasional;

- wholesale or retail;

- corporate or private;

- commercial, non-profit or public-sector;

- civilian or military;

- domestic or export.

We may even have different categories that we simply label ‘good customers’ and ‘difficult’ customers’, however we define them.

Partners

These are the organisations that work with our organisation, for example, to provide specialist services on our behalf. Examples of partner organisations may be a reseller of our products or services or an outsourcing company that provides catering services.

Suppliers

These provide us with the goods and services that we use. Again, we may wish to subdivide them, perhaps into:

- major or minor;

- regular or occasional;

- domestic or overseas.

Suppliers are stakeholders because they are interested in the way we do business with them, what we wish to buy, how we want to pay and so on. Many change initiatives have the effect of altering the relationships of organisations with their suppliers and, as with the customers, such changes need to be managed carefully to make sure that they achieve positive and mutually beneficial results.

Competitors

Competitors vie with us for the business of our customers and they therefore have a keen interest in changes made by our organisation. We have to consider what their reactions might be and whether they might try, for instance, to block our initiative or to produce some sort of counterproposal.

Regulators

Many organisations are now subject to regulation or inspection – either by statutory bodies like Ofcom (Office for Communications) and Ofsted (Office for Standards in Education), or by professional bodies like the General Medical Council. These regulators will be concerned that changes proposed by an organisation are within the letter and spirit of the rules they enforce.

Owners

For a commercial business, the owners are just that – the people who own it directly. The business may be, in legal terms, a sole trader or partnership. Or, it could be a limited company, in which case the owners are the shareholders. For public limited companies, the majority of shares are held by institutions like investment companies and pension funds and so the managers of these share portfolios become proxy owners.

Employees

The people who work in an organisation clearly have an interest in the way it is run and in changes that it makes. In a small firm, the employees may be regarded as individual stakeholders in their own right but, in larger concerns, they are probably best considered as groups. Sometimes, employees belong to trades unions, whose officials therefore become stakeholders too.

Managers

Finally, we have the professional managers of the organisation, those to whom its direction is entrusted. In a large organisation, there may be many layers of management and each may form a distinctive stakeholder grouping, for example:

- board-level senior managers;

- middle managers;

- junior managers;

- front-line supervisors.

As with many aspects of stakeholder management, it is an error to assume that a group like ‘managers’ is homogeneous in its views and concerns; junior managers may well have a very different perspective, and a different set of values and priorities, from those on the board who take the major strategic decisions.

Other stakeholders

Of course, the groups shown in Figure 6.2 are generic and, in particular cases, there may well be other stakeholders. For example, the insurers of an organisation may be interested in any areas that could affect the pattern of risk that is covered. Or perhaps the police might be interested in the law and order implications of some actions. In some organisations, the views of staff associations are also significant.

It is important for each project that the identification of stakeholders is as complete as possible, as it will otherwise be impossible to develop and implement effective management strategies for them. It may be useful to conduct some sort of workshop with people knowledgeable about the organisation and the proposed project to make sure that the coverage of stakeholders is comprehensive.

ANALYSING STAKEHOLDERS

Having identified the stakeholders, the next step is to make an assessment of the weight that should be attached to their issues. No stakeholder should be ignored completely but the approach to each will be different depending on (a) their level of interest in the project and (b) the amount of power or influence they wield to further or obstruct it.

One technique for analysing stakeholders is the power/interest grid illustrated in Figure 6.3.

Figure 6.3 Stakeholder power/interest analysis

In using the power/interest grid, it is important to plot stakeholders where they actually are, not where they should be or perhaps where we would like them to be. We can then explore strategies for managing them in their positions or, perhaps, for moving them to other positions that might be more advantageous for the success of our project.

STAKEHOLDER MANAGEMENT STRATEGIES

There is, of course, an infinite number of positions that could be taken on the power/interest grid but it is probably sufficient here to consider the nine basic situations illustrated in Figure 6.4.

No or low interest and no or low power/influence

These are stakeholders who have neither a direct interest in the project nor any real power to affect it. For practical purposes, they can be ignored as regards day-to-day issues on a project and there needs to be no special effort made to ‘sell’ them its benefits. However, as stakeholders do change positions on the map (discussed below), it is probably wise to inform them occasionally about what is going on – perhaps through vehicles like organisation newsletters.

Figure 6.4 Basic stakeholder management strategies

Some or high interest but no or low power/influence

These groups can be very difficult to manage effectively as, although they may be directly affected by a change project, they feel powerless to shape its direction in any way. This can result in frustration and a passive resistance to change that, though overcome by positional power, can lead to delay and less-than-optimal results.

The basic management strategy here is to keep such stakeholders informed of what is going on and, in particular, of the reasons for the proposed change. But this is a rather passive approach and, in most circumstances, more effort has to be devoted to ‘selling’ the project. This can best be done by being as honest as possible about the need for change; by highlighting the positive aspects of the change or the negative consequences of not making it; and by frequent and focused communication of progress.

No or low to high interest but some power/influence

This is a rather varied group. It includes some stakeholders like middle or senior managers who do have some power or influence but who, because their interests are not directly affected, are not very concerned about the direction a project is taking. Regulators may also fall into this category and they will only start to get involved if some breach of the rules is suspected when they could, in effect, squash an initiative. The group can also include people with more interest in the project but, again, only some power or influence over it.

The best approach with this group is to keep them supportive of the project, possibly by frequent, positive communication with them but perhaps also by involving them more with the project. As the old saying has it, it is better to have them inside the glasshouse throwing stones out than outside throwing them in.

No or low interest but high power/influence

These are probably very senior managers who, for one reason or another, have no direct interest in the project. This may be because it is too small or unimportant for them to bother with or it may be that it is in an area that doesn’t interest them; the Group Marketing Director, for instance, probably will not be concerned about a project to streamline the stationery purchasing procedures. For many purposes, it might be thought that they can be ignored but this is actually a rather risky approach. Our Marketing Director may, for instance, suddenly get very interested in the stationery system if she keeps getting pens that don’t work or can’t get hold of any sticky notes for a conference! So, if a situation arises that might cause them to take a greater interest in the project, we might want to address their needs directly, via one-to-one meetings perhaps, in order to ensure that they do not start to raise concerns or even decide to exert their influence. In some situations it is possible that we may wish to encourage the increased interest of influential stakeholders, for example, if we felt that their support would help achieve the project objectives. Where this is the case, we may need to highlight any aspects of the project that will have a direct impact upon the stakeholder’s business area; some form of discussion will be required which, with very influential stakeholders, would typically involve a meeting.

Some interest and high power/influence

These people have some interest in the project – probably an indirect one as it is happening within or affecting their empire – and they have real power. The usual stakeholder management strategy here is to keep them satisfied and, perhaps, to prevent them from taking a more direct (and hence, possibly, more obstructive) interest in the project. In other circumstances, the strategy may be precisely the opposite – to get the stakeholder more actively involved in a project. For example, if the finance director of an organisation can be persuaded to get positively involved in a project, they will often be a powerful force for success, since they can make resources available that would otherwise be hard to come by.

High interest and high power/influence

These are the key players, the people who are both interested in the project and have the power to make it work or not. Often, the key players are the managers of the functions involved in a project. Initially, it is important to determine if individual key stakeholders are positive or negative in their approach to a project. If positive, then their enthusiasm must be sustained, especially during times of difficulty. It is also important to appreciate the concerns and opinions of key stakeholders and you will need to take these into account when making any recommendations. For example, if one of the key stakeholders has a particular solution in mind it is important to know about this as early as possible in order to ensure that, at the very least, the solution is evaluated as one of the options. It is also vital that the key stakeholders understand the progress of the project and why certain decisions have been made. These are the people to whom any final recommendations will be presented and who will have the final say on any decisions. They need to be kept informed at all stages of the project so that none of the recommendations come as a shock to them.

Those key players who are negatively inclined towards a project can be managed in various ways, depending on the circumstances:

- By far the best approach is to find some personal benefits for them in the proposed course of action. The stakeholder perspective analysis techniques described below can be very useful here.

- Alternatively, a more powerful counterforce must be found to outweigh their negative influence. This may mean engaging the interest of someone in one of the high power areas of the grid.

Individuals and groups of stakeholders

An individual customer may not be of much concern to an organisation such as a big supermarket chain. But if they post a negative review using social media, write to newspapers, organise petitions or complain to consumer groups, they can increase their level of power considerably. A lot of ‘people power’ can damage even large concerns considerably and force them into major reversals of course. The classic example of this is the mighty Coca-Cola being forced to reintroduce its traditional Coke in the face of a massive worldwide customer revolt against a new formula. Similarly, individual employees can be marginalised by an organisation but, if they are members of a trade union, their power is greater. A single government employee who objects to a policy may be relatively powerless but if they ‘blow the whistle’ to national newspapers, they can cause considerable difficulty.

These examples illustrate the dangers of ignoring the weakness of an individual or mistaking individual weakness for collective weakness. Stakeholders must be considered not just as individuals but as potential groups as well. Their ability to gain strength, particularly with the availability of social media mechanisms, should never be underestimated.

SUMMARY OF STAKEHOLDER MANAGEMENT STRATEGIES

The basic strategies for stakeholder management are summarised in Figure 6.4 but individual stakeholders will not fit neatly into one of the nine types and management approaches must be tailored for each. Also, as we shall discuss in the next section, stakeholders do not stay in the same place over time and so the ways they are managed must be adapted accordingly.

MANAGING STAKEHOLDERS

Stakeholders’ positions on the framework in Figure 6.4 do not remain static during the life of a project. At the most obvious level, a manager may get promoted so that, from being in the high interest/low power situation, is now both interested and powerful. Alternatively, the manager may lose interest in a project if promoted into a job with a wider remit. The circumstances of an organisation may change so that senior managers begin to focus more on IT projects. A scandal within a competitor organisation may cause a regulator to take a closer interest in all companies in a sector. This means that stakeholder analysis must be a continuing activity throughout the project – and even afterwards to find out what the stakeholders thought of the final outcome. The project team and project manager should be constantly on the lookout for changes in stakeholders’ positions and should be re-evaluating their management strategies accordingly. Once stakeholders’ initial positions have been plotted, a plan should be drawn up for managing each of them and how to approach it. A one-page assessment can be made for each stakeholder but a more useful approach would be to see all stakeholders at a glance by setting up a spreadsheet using the following headings:

Name of stakeholder

It may also be useful to record their current job titles.

Current power/influence

From the grid.

Current interest

From the grid.

Issues and interests

This is a brief summary of what interests each stakeholder and what we believe their main issues with the project are likely to be.

Current attitude

Here, we need to devise a classification scheme, perhaps using the following descriptions:

- Champion: will actively work for the success of the project.

- Supporter: in favour of the project but probably will not be very active in promoting it.

- Neutral: has expressed no opinion either in favour or against the project.

- Critic: not in favour of the project but probably not actively opposed to it.

- Opponent: will work actively to disrupt, impede or derail the project.

- Blocker: someone who will just obstruct progress, possibly for reasons outside of the project itself.

Desired support

What we would ideally like from this stakeholder, perhaps using a simple scale of high, medium or low.

Desired role

We may wish to get this stakeholder actively involved in the project, perhaps as the project sponsor or as part of a steering committee.

Desired actions

What we would like the stakeholder to do, if at all possible, to advance the project.

Messages to convey

This is where we define the emphasis that should be put on any communications to this stakeholder. For example, we might need to identify and highlight any issues that are of particular interest to this stakeholder. The messages are likely to be tailored to each stakeholder and so the more we know about them and their concerns, the more effective our communications will be.

Actions and communications

This is the most important part of the plan, where we define exactly what actions we will take with regard to this stakeholder. It may be just to keep them informed, in a positive way, about the project and progress to date. Alternatively, it may be a more active approach, for example meeting them to engage their interest in the project. Where a strategy has been devised to change a stakeholder’s position – perhaps to encourage someone to take a closer interest – then its success must also be evaluated and other approaches developed if the desired results are not being achieved. As mentioned earlier, the high interest/high power stakeholders are the key players and require positive management, such as frequent meetings and discussions about the direction the project is taking. This will help make sure that they are kept informed about a project and are happy with the approach that we are taking. Perhaps just as important, we will understand when their opinions or issues have changed and will reflect this in the project direction and work as appropriate.

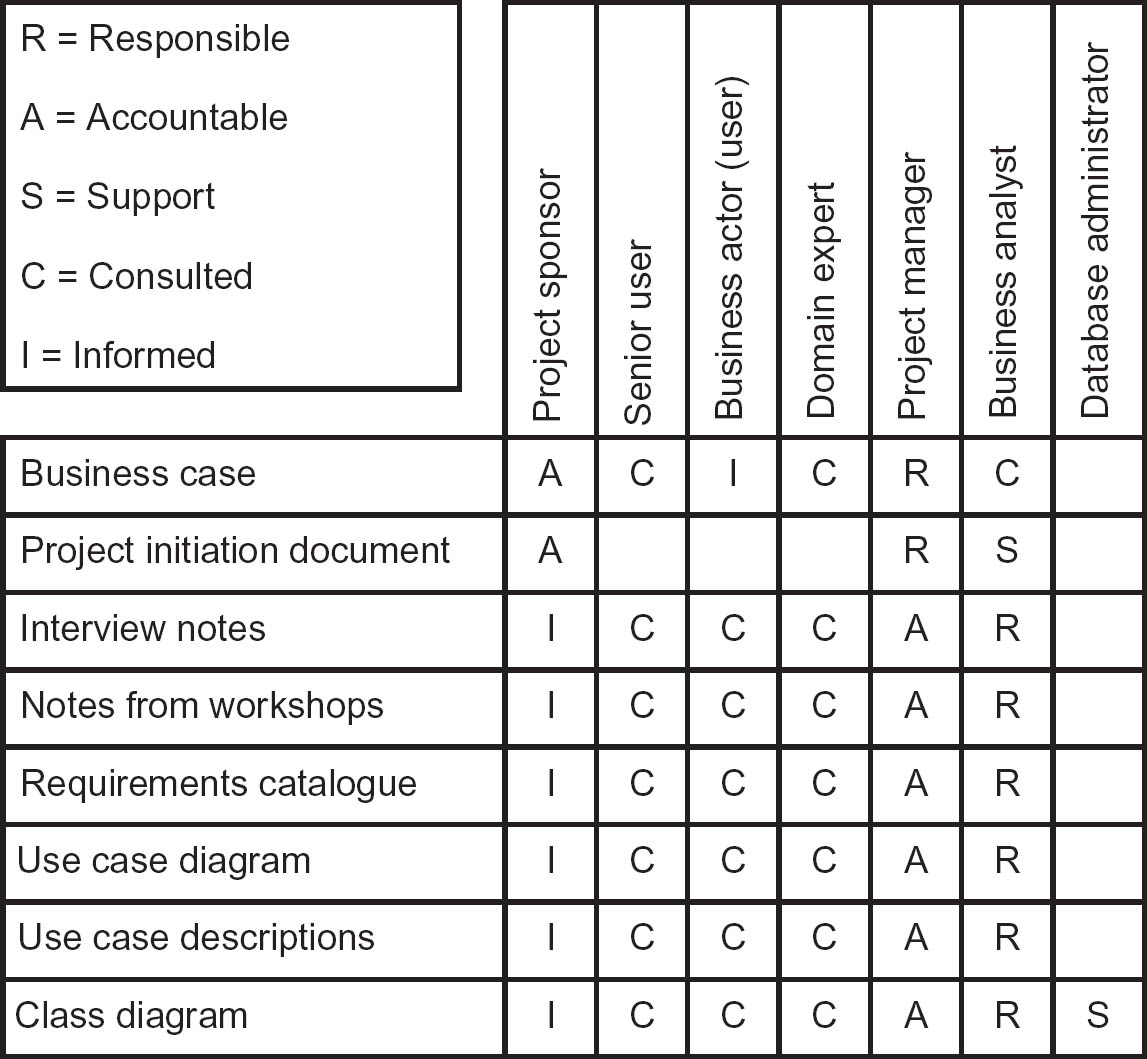

DEFINING STAKEHOLDER INVOLVEMENT – RACI AND RASCI CHARTS

Apart from deciding on the management strategy for the various stakeholders, it can also be very useful in a business analysis project to consider the tasks or deliverables and the extent to which the stakeholders are involved with them. A simple and effective method for achieving this is to create a RACI chart as illustrated in Figure 6.5.

A RACI chart – more formally known as a ‘linear responsibility matrix’ – lists the main products/deliverables down the side and the various stakeholders along the top. Where a stakeholder intersects with a product, we indicate their involvement using one of the RACI categories, which mean:

Figure 6.5 RACI chart (Reproduced by permission of Assist Knowledge Development Ltd)

- Responsible: This is the person or role responsible for creating or developing the product or performing the task. In Figure 6.5, for example, a business analyst is responsible for creating the interview notes.

- Accountable: The person or role who will ‘carry the can’ for the quality of the product or task. The project sponsor, for instance, must ultimately be accountable for the business case for a project.

- Consulted: This person or role provides information that is input to the product or task. In Figure 6.5, the senior user, other business actors and the domain expert are shown as being consulted during the interviews and workshops.

- Informed: These stakeholders are informed about a product or task, though they may not have contributed directly to them. For example, the project sponsor has the right to be kept informed about any of the products being produced during the project.

A RASCI chart, shown in Figure 6.6, uses a similar approach but has an additional category S for ‘support’. This person (or role) will provide assistance, and sometimes resources, to whoever is responsible for the product/deliverable. For example, in Figure 6.6, the business analyst is shown as supporting the project manager in the creation of the project initiation document and the database administrator supports the business analyst in developing the class diagram.

Yet another scheme that could be used on a linear responsibility matrix includes I (initiation), E (execution), A (approval), C (consultation) and S (supervision).

Figure 6.6 RASCI chart (Reproduced by permission of Assist Knowledge Development Ltd)

USING SOCIAL MEDIA IN STAKEHOLDER MANAGEMENT

Once upon a time, in stakeholder management, there really was no alternative to coming into an organisation ‘cold’ with little understanding of who was who and where they fitted in. However, the availability of social media offers the business analyst additional resources to learn about stakeholders and to manage the relationships with them.

One obvious way of using social media is to use sites such as LinkedIn to carry out research about stakeholders. What is their role? What have they done previously in their careers? Do we have any contacts in common who could introduce us?

Once the business analysis project is underway, other forms of social media might be considered for communicating with stakeholders. For example, when considering the ‘low/low’ category in Figure 6.4 we said that these stakeholders could effectively be ignored as they have no direct interest in or influence over the project. However, resources such as Facebook and Twitter offer a cost-effective way of communicating with large groups of people on a frequent basis and keeping them informed. This can help to build a sense of community and make people feel involved in what is going on.

UNDERSTANDING STAKEHOLDER PERSPECTIVES

Introduction

It is all very well knowing who the stakeholders are and what is likely to be their influence on a business analysis project. It is also important to understand their attitude – how supportive are they of what we are trying to achieve? But it is also vital to understand what they think, in other words what are their business perspectives? For example, in a commercial organisation, one stakeholder might feel that any activities are allowable as long as they are not actually illegal, whereas other stakeholders may feel that the organisation has some responsibility towards society at large and therefore conclude that some activities should be avoided on ethical grounds.

To help us understand these stakeholder perspectives, and to model the different business systems that would fulfil them. we can utilise some of the elements from Peter Checkland’s Soft Systems Methodology (SSM; Checkland 1999).

Soft Systems Methodology

Peter Checkland and his team at Lancaster University devised SSM in the 1980s as a way of understanding complex real-world situations. The basic premise underlying SSM is that real-world situations are rarely simple and are often very complex. An approach to business analysis, based upon elements and concepts from the SSM, is illustrated in Figure 6.7.

Figure 6.7 Business analysis using SSM concepts

When investigating business situations, it is often the case that stakeholders have different views about what the ‘problem’ is and also about what needs to be done. As Figure 6.7 shows, there are five main stages that should be applied:

- The situation is identified, for example the loss of market share by a company or the poor public perception of a public body, and the issues and causes are investigated.

- Stakeholders’ views – perspectives – are sought about what the organisation is about, what it should be doing and so forth.

- From each stakeholder’s perspective, a conceptual model is created to show what the organisation should do to fulfil the perspective.

- These conceptual models are compared with the real-world situation and a consensus model is generated, possibly by combining elements from various stakeholder’s perspectives.

- Actions are defined to address the situation by implementing the consensus model in place of whatever is happening currently in the organisation.

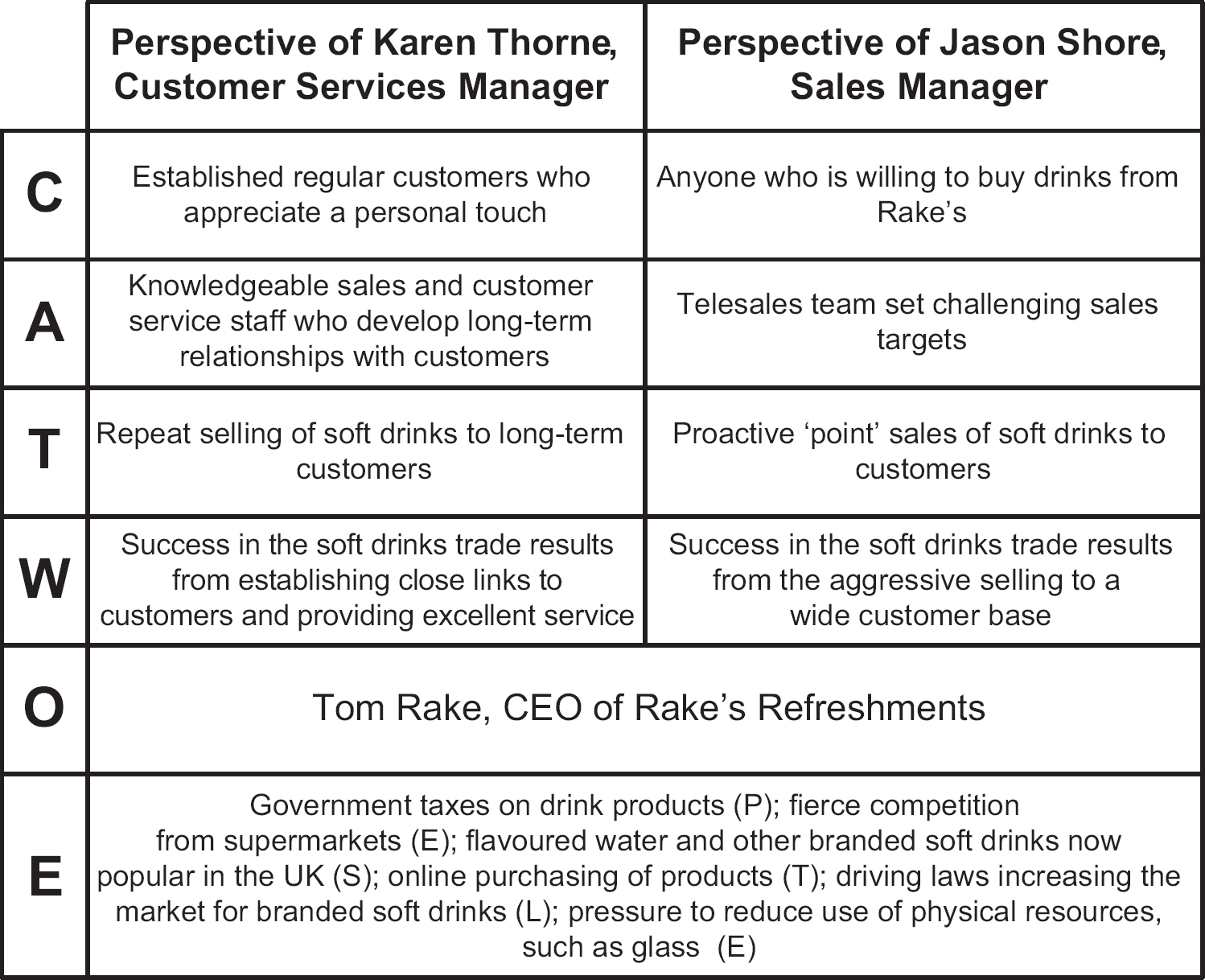

Analysing the perspectives – CATWOE

SSM provides us with a very useful tool that we can use to explore the stakeholders’ perspectives. Although the technique is known as CATWOE, experience shows that exploring the CATWOE elements is actually best done in the following order:

- W = Weltanschauung or worldview This summarises a stakeholder’s beliefs about the organisation or business system, which explain why it exists and what it should be doing. If we consider the soft drinks merchant business that was discussed in Chapter 5, the newly appointed Sales Manager believes that success in the soft drinks trade results from proactively contacting potential customers and convincing them to buy. However, the Customer Services Manager believes that success results from establishing close links with regular customers and providing them with excellent service.

- T = Transformation This is the principal business activity of the business system, in other words what lies at the heart of its operations. (Checkland used the term ‘transformation’ here because, at the highest level of abstraction, all systems exist to transform some form of input into some form of output.) In the case of the drinks supplier, the Sales Manager’s worldview leads to a transformation that consists of making one-off ‘point sales’, whereas the Customer Services Manager thinks that it is about providing a high quality of service throughout the sales process, in order to establish relationships with customers.

- C = Customer(s) Stakeholders can differ, too, in their views of who their customers are (or should be). In our example, one view might be ‘anyone willing to buy from us’ whereas another might be ‘established regular customers who appreciate a personal touch’. Another way of thinking about customers is to ask ‘who is on the receiving end of the transformation?’

- A = Actor(s) These are the people who carry out the transformation, for example telesales staff set challenging targets or knowledgeable salespeople and customer services staff capable of establishing long-term relationships with customers.

- O = Owner(s) The perspective is someone’s view of a business system, so the question is who ultimately controls that system and who could instigate change, or even closure, if necessary. Who, for example, could decide between the two competing worldviews about the drinks supplier? In this case, the owner is the business’s chief executive but, in other situations, it could be a group, like a board of directors.

- E = Environment Finally, all organisations operate within the constraints imposed by their environment. PESTLE – explored in Chapter 3 – can be used to identify the main external factors but, in some situations, things like organisational policies can also feature here.

Figure 6.8 presents CATWOE analyses from the two stakeholders’ perspectives.

Figure 6.8 Contrasting perspectives for Rake’s Refreshments

In Figure 6.8, the owner and environment for both perspectives is the same. This can be the case when using CATWOE, although sometimes different perspectives may yield differences in these areas. For example, we might consider a further environment constraint to be the willingness of people to buy soft drinks on receipt of an unsolicited telephone call.

Illustrating the perspectives – business activity models

Business activity models (BAM) provide a conceptual model of what we would expect to see to fulfil a particular stakeholder perspective. A BAM shows what the organisation should be doing, as opposed to a business process model (discussed in Chapter 7) which explores how it does these things.

Creating a BAM requires the business analyst to think about the activities that each stakeholder’s perspective implies. Initially, there will be one BAM for each distinct perspective. At a later point, these are examined in order to identify where there is agreement or conflict between the BAMs. Ultimately, the aim is to combine them and, in discussion with the stakeholders, achieve a consensus BAM.

The approach for creating a BAM is as follows and a completed BAM for Rake’s Refreshments (drawn from the perspective of the Sales Manager) is shown in Figure 6.9:

- Identify the DOING activities that are at the heart of the model. These are derived from the transformation of CATWOE and reflect the organisation’s principal business activities. In the case of the drinks supplier, there is one doing activity ‘sell soft drinks’.

- ENABLING activities are next added. These lead into the doing activities on the model and acquire or replenish the resources needed to carry them out. In Figure 6.9, for example, there are activities to recruit and train salespeople and to advertise the company’s products.

- All of the activities of the organisation should follow from PLANNING activities. Normally, on a BAM, we would not show the strategic planning activities – setting the general direction of the organisation for instance – as we are interested in the planning required within this business system (which will support the strategy execution). In Figure 6.9, we plan how many salespeople are needed, and what skills they require, and we plan how best to market the products to the customers. Planning activities also include setting targets, such as KPIs (discussed in Chapter 3) against which the performance of the business system can be measured.

- The actual evaluation of the performance is done within the MONITORING activities, for example, in Figure 6.9 monitoring the performance of the salespeople.

- Finally, if the monitoring activities reveal that performance is not what was expected in the plans, CONTROL activities may be required to institute the necessary remedial actions.

Figure 6.9 Business activity model for Rake’s Refreshments

With regard to the control activities, two observations are relevant:

- On a BAM, we could associate a control activity with each monitoring activity and some users of the technique prefer to shown them this way. However, in the real world, managers often take action as a result of a range of measurements so a less cluttered model can be created by feeding all of the monitoring activities into one control activity, as in Figure 6.9.

- The control actions themselves could feed back into any of the other activities on the model. Since trying to show this would create an impossible-to-understand diagram, the convention is to show a ‘lightning strike’ symbol emanating from the control activity which means that it feeds back into the model wherever it is relevant.

The model shown in Figure 6.9 represents Rake’s Refreshments as seen from the perspective of Jason Shore, Sales Manager. As we have seen, though, the Customer Services Manager, Karen Thorne, sees the organisation rather differently. Both managers agree that ‘Sell soft drinks’ is at the heart of the business but, for Jason Shore, this means proactively contacting new customers and pushing them to buy Rake’s Refreshments; Karen envisages selling to existing customers who contact Rake’s to ask for advice and guidance on what to buy. If the model had been built from Karen’s perspective, it would probably not contain the enabling activity E6 ‘Prospect for customers’ but it would have included activities to recruit and train customer service staff, possibly as brand advisors. There would also have been an activity to monitor the level of customer satisfaction.

Having modelled the organisation from the perspective of each stakeholder (or, at any rate, of each stakeholder with a different CATWOE), it is now necessary to achieve a consensus BAM that represents the agreed or idealised way forward. Ideally, this is achieved through negotiations involving the stakeholders and the business analysts; the aim is for the stakeholders to all ‘buy in’ to the final BAM. Realistically, however, sometimes the stakeholders just cannot agree and this is where identifying the ‘owner’ of the business system (as in CATWOE) is important. The owner has to choose between the competing BAMs or perhaps impose one that is a composite of several. This is less desirable than securing all the stakeholders’ agreement, as some people may not necessarily accept the agreed BAM but it may be the best that can be achieved in some situations.

The consensus BAM is an extremely valuable product for a business analyst as it provides a model of what the business system should look like and should be doing. Insofar as the actual situation on the ground differs from this conceptual view, this provides a means of considering opportunities for improvement. Examination of the difference between the current situation (perhaps reflected in a range of documents including meeting reports, a rich picture or fishbone diagram – see Chapter 5) and the conceptual view provided by the BAM, is an important part of gap analysis and is discussed in Chapter 8. As part of the gap analysis, the business analyst may wish to explore how the activities are currently carried out, and how they should be performed in the future; this can be achieved through business process modelling covered in Chapter 7.

A note on notation for business activity models

There is no universally agreed notation for BAMs. Many users of the technique like to use ‘cloud’ or ‘thought’ symbols to emphasise that this is a conceptual model and not a representation of what the organisation looks like now. In Figure 6.9, we have used ovals for the practical reason that they take less space than clouds and are easier to draw free hand. It is probably not a good idea to use boxes, as then the models may be confused with business process models which, as we have shown, illustrate how an organisation works rather than what it does.

Activity ‘threads’ in business activity models

Sometimes, rather than considering individual business activities, it is more useful to group them into ‘threads’ of related activities. For example, in Figure 6.10, we have extracted from Figure 6.9 those activities related to the recruitment, training and management of salespeople. (Activities E6 and D1 are shown for completeness but are not relevant to this investigation.) The reason for this is that perhaps we would like to consider the entire way in which the organisation recruits, trains, measures and controls their salespeople (and maybe other staff too). We may find, for example, that the jobs are poorly defined, ineffective recruitment processes are being used, salespeople are being set the wrong targets and so on.

Figure 6.10 Thread of business activities relating to staff management

SUMMARY

Effective stakeholder management is key to the success of any business analysis project. It should begin before the project starts, at the inception stage, and be continued throughout the project – and even afterwards to ensure that the changes are implemented effectively. Although the project manager has the key responsibility in this area, all team members have roles to play. Stakeholders can be assessed in terms of their interest in the project and their power or influence over it and strategies must be defined to actively manage them in accordance with this assessment. The stakeholder perspectives should also be explored in order to uncover strongly held beliefs and potential conflicts. Techniques such as CATWOE and BAM are extremely helpful in revealing where the stakeholders’ values and priorities lie, and exploring what should be done within the business system to fulfil their perspectives.

REFERENCE

Checkland, P. (1999) Systems Thinking, Systems Practice: Includes a 30 year retrospective. Wiley, Chichester.

FURTHER READING

Johnson, G., Scholes, K. and Whittington, R. (2008) Exploring Corporate Strategy, 8th edn. FT Prentice Hall, Harlow.

Rodney Turner, J. (2014) The Handbook of Project-Based Management, 4th edn. McGraw-Hill, New York.