INTRODUCTION

When business analysts first enter an area of study, they need a range of tools and techniques to help them understand the breadth and depth of issues. While they will be making use of background research, workshops, one-to-one interviews and quantitative methods of verification of data, they must also use diagnostic tools for understanding a problem area, and different approaches to documenting their findings, according to the focus. This chapter will look at a range of techniques used to investigate business areas and document the findings.

The assumption behind this chapter is that the analyst will be responsible for performing a broad study that begins with a general understanding of the situation, then produces a diagnosis of the underlying causes and subsequently understands the requirements for a solution. The terms of reference for most analysis studies will be significantly narrower than that; nevertheless, all the techniques to be described in this chapter will be useful at one time or another. We advocate a toolbox approach to analysis rather than a strict checklist method, and the more tools available, the more flexible and responsive the analyst can be.

PRIOR RESEARCH

When an analyst first approaches their client organisation, (or division or department), they should first spend time gathering as much background information as they can. There are various sources available, but the internet has made access to such background information much simpler than before.

Study website

This is the quickest and simplest way to get a view of what the organisation does, what its values are, how it brands itself and how it wants to be perceived. Depending upon the nature of the organisation the website should provide access to information about the products and services, opportunities to interact with the site and give feedback, and offer details about the company.

At this stage you will be looking particularly at its branding, its apparent values and priorities, how easy it is to navigate and interact with the site. If it gives feedback or reviews from customers, it is worth looking at those, particularly if any are less than whole-heartedly positive. However, such reviews are likely to be selected to show the company in its best light. It may be worth exploring customer reviews on other sites such as those that review hotels or restaurants.

One useful inference from the design of the website is how the company views its place strategically, in terms of the balance between the cost and the perceived quality of its products. The design of the website will often give an indication of the level of quality it aims at: primary colours, flashing icons, liberal use of exclamation marks and free use of suggestive words like ‘Bargain!’ imply a more populist approach, while a quieter background, carefully composed photographs, moderated colours, all imply a concern for a perception of quality. Interpreting a website in this way can provide an early insight into the business imperatives for the organisation.

We can also evaluate the ease of navigating around the site, placing an order or making an enquiry. These things will give an idea of the level of professionalism of the site and expected standards of technology presentation and achievement. This in turn can provide clues about the technological maturity of the company – is the technology aligned to the business intention, or are the developers showing off their skills at the expense of the company’s message?

Study company reports

If we are approaching a commercial company in the role of an external consultant, it is useful to look at company reports to confirm the health of the company. Companies with limited liability are required to file statutory documents reporting on their financial position. For example, UK companies are required to file the Income Statement (Profit and Loss Account) and Balance Sheet with Companies House, from where they may be accessed by the public. These documents can provide much rich information about the levels of debt, liquidity, gearing, trends in growth or stagnation over the previous years, and a first insight into where there may be problems. The shareholders’ reports will also set out the future direction of the company as agreed by the Directors, and state the targets and aims for the next year. Again, the report should explicitly explain the target market and strategy intentions, which will give the analyst insights into the business perspectives.

Studying these reports at the outset of a project can also save later unnecessary effort and avoid financial loss. As an example, following an invitation to carry out consultancy work for a new client, an examination of the company’s entry at Companies House revealed that it was about to be suspended for non-submission of accounts over the previous two years. A failure to carry out this research could have ended with unpaid invoices and wasted effort.

Study procedure manuals and documentation

Many business analysis projects will have a scope that is more local than those suggested above, and more focused on specific sets of processes. The prior research for such projects will include studying current system documentation and any procedures manuals. These are to give an idea of the expected ‘as-is’ process, but another note of caution – over time such documentation will naturally become unrepresentative of the actual course of the process. It will tell you not so much the ‘as-is’ description as the ‘what-we-thought-it-ought-to-have-been’.

Studying the documentation is never a substitute for proper investigation and analysis; rather it enables preparation, a prior understanding of the domain in question that gives the analyst an entry point for various lines of investigation.

Study the organisation chart

The organisation chart sets out the management structure of the organisation and can offer insights into the style and culture of the organisation. Understanding the job roles and reporting lines is a valuable preparation for the more detailed investigation to follow.

INVESTIGATION TECHNIQUES

There are many reasons that business analysis is required. For example, a study might be to investigate an area of concern, diagnose a weakness in the business processes or compile the requirements for a new system. After the prior research has been done, the analyst needs to consider how to conduct the more detailed investigation. There will be a variety of techniques available, depending upon the size of the domain in question, its location, the number of stakeholders to be consulted, and the nature of the information to be ascertained.

The techniques can be categorised broadly as qualitative, understanding what is needed, and quantitative, concerned with volumes and frequencies. Qualitative techniques can be further broken down into one-to-one sessions and collaborative sessions. The most common of the qualitative one-to-one approaches to investigation are the interview, a meeting with individual stakeholders and shadowing sessions. Collaborative approaches include workshops and focus groups.

INTERVIEWS

The interview is a key tool in the business analyst’s toolkit. A well-run interview can be vital in achieving a number of objectives. These include:

- making initial contact with key stakeholders and establishing a basis for the business analysis work;

- building and developing rapport with different business users and managers;

- acquiring information about the business situation, including any issues and problems;

- discovering different stakeholder perspectives and priorities.

Interviews tend to take place on a one-to-one basis, which is a key reason why they can be invaluable in obtaining personal concerns. They focus on the views of an individual and provide an environment where the interviewee has an opportunity to discuss their concerns and feel that they are given individual attention. However, interviewing can be quite time consuming so the analyst has a responsibility to ensure that the interviewee’s time is not wasted, the required information is acquired and a good degree of understanding and rapport is achieved.

There are three areas that are considered during fact-finding or requirements interviews:

- current functions that need to be fulfilled in any new business system;

- problems with the current operations or performance that need to be addressed;

- additional features required from the new business system.

The last point can be the hardest part of an interview, as we are asking business users to think beyond their experience. They may offer vaguely worded suggestions and so the skill of the interviewer is needed to assess the implications of the initial suggestions and draw out more detailed information.

Advantages and disadvantages of interviewing

One of the major benefits of conducting an interview is that it provides an opportunity to build a relationship with the users or clients. Whether we are helping the business to improve operations, solve a specific issue or replace a legacy IT system, it is critical that we understand the perspectives of the people involved with the business system. This means that we need to appreciate what they do, their concerns and what they want from any new processes or systems. For their part, the users need to have confidence in the analysts, to know that we are aware of their concerns, are professional, and are not leaping to implement a solution that overlooks the user’s own needs and worries. Taking time to form good relationships early on in the project will increase the opportunities to understand the context and details of the business users’ concerns and needs.

The second major benefit is that the interview can yield important information. The focus of the information will vary depending upon the needs of the project but will usually include details about the current operations, including difficulties in carrying out the work, and will help with the identification of requirements for the new business system.

Additional advantages of interviews include:

- providing an opportunity to understand different viewpoints and attitudes across the user group;

- providing an opportunity to investigate new areas previously not mentioned;

- enabling the analyst to identify and collect examples of documents, forms and reports the clients use;

- allowing an appreciation of political factors that may affect how the business performs its work;

- providing an opportunity to study the environment in which the business staff carry out their work.

While interviewing is an effective technique, there are some disadvantages. Interviews take time and can be an expensive approach, particularly if the business users are dispersed around the country. They take up the interviewee’s time, which is often difficult to be spared from a busy schedule, and this may mean that they try to hurry the interview or resent the time that it takes. It is also important to realise that the information provided during interviews may be an opinion from just one interviewee’s perspective, requiring confirmation by quantitative data before any firm conclusions can be drawn. Where several different interviewees have different views the analyst will also have to coordinate these views and identify any gaps and conflicts. This may create a need for follow-up discussions and further investigative work.

Preparation for interviewing

The interviewing process is greatly improved when the interviewer has prepared thoroughly. This saves a lot of time by avoiding unnecessary explanations and also demonstrates interest and professionalism, which helps to establish a mutual respect and rapport.

The classic structure of who?, why?, what?, when? and where? provides an excellent framework for preparing for interviews.

Who?

This involves identifying which stakeholders you will interview and considering the order in which they will be interviewed. We usually begin with the more senior stakeholders as this helps us to understand the context for the problem before moving to the details so it is useful to interview someone who can provide an overview. A senior person is also able to identify the key people to see and make any necessary introductions.

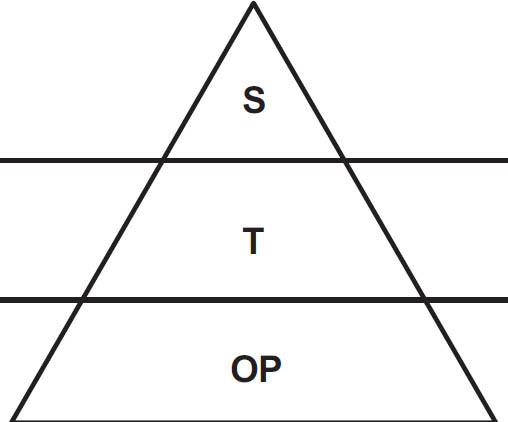

The level of authority of the interviewee will dictate the nature of the questioning. The STOP model (Figure 5.1) illustrates a simple hierarchy.

Figure 5.1 ‘STOP’, the organisation hierarchy

- The ‘S’ represents the strategic level of management. Our concerns at this level are to:

- The ‘T’ represents the tactical level, or middle management. Here we are concerned with understanding issues of performance, targets and management control. We should be able to understand the Critical Success Factors (CSF) and Key Performance Indicators (KPI) that have been chosen (see description of CSF/KPIs in Chapter 3) and any associated reporting requirements. These interviewees will be able to tell us what processes and functions are carried out in the department, and who the key people are, but we should not expect detailed descriptions of how the processes are executed. The tactical level interviewees should be aware of higher-level strategic decisions and hence able to identify any new business requirements for this area.

- The ‘OP’ level represents the operational level, the people who perform the actual tasks of the department. These are the people who can describe accurately the existing business situation, and can identify problems and workarounds to deal with the current procedures. They have information about source documents, bottlenecks and the flow of the work, and are likely to provide ideas about the volumes of work (although these need to be treated with caution and should be analysed using quantitative investigation techniques).

The questioning strategy for the interview will depend upon several factors, including where the prospective interviewee sits in the hierarchy, the objectives for the project and the nature of the issues to be discussed.

Why?

This involves considering why a particular interviewee is to be interviewed and the place of the interviewee in the organisation, as described above. The objectives of the interview may range from the detailed elicitation of business needs to just establishing a good rapport and working relationship with a key stakeholder. The forms of questioning and of note-taking will differ significantly depending upon the objectives of the interview.

What?

This involves considering the information that could be provided by an interviewee and the areas you might explore during the interview. Answering the ‘what?’ question helps identify the items to be discussed during the interview and provides the foundation for the agenda. Issuing an agenda two days or so before the interview helps to focus the mind of the interviewer and enables the interviewee to prepare by considering in advance the information required.

When? and where?

These questions involve considering the venue, timing and duration of the interview. Typically, the interviewee will dictate the exact timing and duration, as this will depend upon availability. Limiting interviews to a maximum length of one hour is a good idea since:

- The majority of interviewees will be busy with numerous work commitments so may have trouble finding slots of more than an hour in their diaries.

- It can be very difficult to concentrate for more than an hour so longer interviews are often unproductive. This applies to both interviewer and interviewee.

- The longer the interview the harder it is to write up the notes accurately.

The ‘where’ is restricted to three possibilities: the interviewee’s place of work, the interviewer’s place of work, a neutral third location. The first of these is recommended for the initial interview with a particular stakeholder for the following reasons:

- This is the interviewee’s own territory where he or she is likely to feel at ease and less apprehensive. Meeting interviewees at their place of work also sends a signal of respect.

- The interviewer has an opportunity to informally observe the working environment, the culture of the organisation and the frequency and nature of any interruptions.

- The interviewee should have all relevant source documents, reports and screens to hand, instead of having to take additional actions after the interview.

For subsequent meetings and interviews the two parties can agree on a mutually convenient location. The analyst should have established a good working relationship by the end of the first interview session, so the venue is of less concern.

Conducting the interview

It is important to structure interviews if the maximum amount of information is to be elicited using a basic structure of introduction, body of interview and close, as shown in Figure 5.2.

Figure 5.2 The structure of an interview

The introduction

In addition to making personal introductions, it is also important that the analyst makes sure the interviewee understands the purpose of the project in general and the interview in particular. Ideally, the interviewee should know this but such knowledge cannot be relied upon. Explaining the context helps to put the interviewee at ease and will help them to provide the relevant information. It is important to make sure that the interviewee has received the agenda and that any points they wish to raise are clarified.

The main part of the interview is where the facts and issues are uncovered. It is useful to think about how you are going to structure this. A good approach is to begin by obtaining a context for the information this interviewee can provide. This context will usually cover the responsibilities of the interviewee, and their range of responsibilities. Once we have a context, we can structure the interview by examining each relevant area separately and in detail. This will enable us to consider the issues, and the impact of those issues, in each area and to uncover any specific problems and requirements.

It is essential to take notes during the interview. Even if you have an excellent memory, you will not remember everything discussed during the interview. If the purpose of the interview is to understand a current procedure, a good way of taking notes can be to draw a diagram, such as a flow chart. If the purpose is to discuss a number of broader issues, including needs for the future, a mind map is a useful way of noting what has been said, and also, if drawn up as part of the preparation, provides an easy visual check on what has been covered and further areas for discussion. This can be important as however well you have structured your questions in your preparation, conversations always take unexpected loops and diversions. It is important to allow the discussion to detour into other areas, as it helps to gain further insights. In these circumstances, using a diagram to help keep the interview structure in mind can be invaluable.

In some situations it is appropriate to use a portable digital recorder to capture the interview in preference to writing notes. This can be very useful to ensure that all of the details are captured. However, many people feel self-conscious when being recorded and the analyst must be sensitive to the interviewee’s comfort. It should also be remembered that using a recorder will involve a considerable overhead: it can take up to an hour to transcribe ten minutes worth of conversation.

Closure

It is important to close the interview formally. The analyst should:

- Summarise the points covered and the actions agreed.

- Explain what happens next, both with regard to the particular interview and the project. We will usually want to advise the interviewee that we will send them a copy of the written-up notes so that they can check for any errors.

- Ask the interviewee how any further contact should be made; managing the interviewee’s expectations of future behaviour can be extremely useful and will be invaluable if we need any additional information or clarifications at a later point. This also serves to keep the door open for a future interview session if required.

Following up the interview

It is always a good idea to write up the notes of the interview as soon as possible – ideally straight away and usually by the next day. If it is not possible to write up the notes immediately you will find this task easier if you read through them immediately after the interview, and extend them where they are unclear. Once the notes are completed, they should be sent to the interviewee to confirm that they reflect accurately the substance of what was discussed. After they have been approved, they should become a formal part of the project documentation and be filed accordingly.

OBSERVATION

Observing the workplace, and the staff carrying out their work, especially early in an investigation, is very useful in obtaining information about the business environment and the work practices. There are several different approaches to observation, depending upon the level and focus of interest: formal observation, shadowing, protocol analysis and ethnographic studies. These are all explained in more detail below.

It is important that before any work is observed, the person being observed should be reassured that the objective is to understand the task not to judge their performance. Care is needed if you want to observe a unionised work-site to ensure that approval is also gained from the trade union representatives and that any protocols are observed.

Advantages and disadvantages of observation

The views of the stakeholders involved in a project may have been sought during interviews but, to really obtain a feel for the situation, the analyst needs to see the workplace and business practices. Apart from collecting actual facts it is also possible to clarify areas of tacit information and hence increase understanding. This has the following advantages:

- We obtain a much better understanding of the problems and difficulties faced by the business users.

- Seeing a task performed will help us prepare appropriate questions for a more in-depth interview with the person responsible for that task.

- It will help us to devise workable solutions that are more likely to be acceptable to the business.

Conversely, being observed can be rather unnerving and the old saying ‘you change what you observe’ needs to be factored into the approach taken and resultant findings.

Formal observation

Formal observation involves watching a specific task being performed. There is a danger here of being shown just the standard practice without any of the everyday variances, but it is still a useful tool to understand the environment. It is important that the staff members being observed are prepared beforehand and are aware that this is in order to understand the task not, as many will fear, in order to assess their competence and performance. Self-consciousness can influence how the staff member performs and a lack of prior notice will serve to accentuate this problem. If the staff members perceive the observer as having been sent by management, they are more likely to perform the task according to the rulebook, rather than how it has evolved over time.

It is perfectly acceptable to ask people being observed about the sequence of steps they are following, so long as:

- The question does not sound critical of the way the person is working, either in words or tone of voice.

- It does not distract from their performance of the job. The analyst must position themselves in such a way that they can see clearly all that is happening, but do not get in the way or otherwise interfere with the task.

To get full value from the observation, it is beneficial to watch the staff members perform the task several times in order to understand the standard sequence, any possible exception situations and how they are handled, timings for the task and any ergonomic factors or physical working conditions that may enhance or hinder performance.

Physical tasks such as handling goods in a warehouse, or despatching consignments to customers are clearly more susceptible to formal observation than, say, data entry. However, observing more sedentary tasks, such as manning a customer services helpline, or telesales can still provide a lot of useful information, for example, to understand where problems are arising or to elicit requirements for a new system. When watching a physical task, it can be helpful to sketch the layout of the workplace and where the various actors in the task are stationed. Having such a sketch will help with later reflection and analysis of the results.

Protocol analysis

Protocol analysis involves asking the users to carry out a task and describe each step they perform. It is a way of eliciting information about the skills required to complete a task that cannot be described in words alone. The higher the level of unconscious skill involved in a task, the harder it is to explain verbally. Protocol analysis uses a ‘performing and describing’ approach which can be extremely helpful for analysts to gain greater understanding. A similar approach may be used to train a new member of staff or someone unfamiliar with a task. For example, rather than teaching new learner drivers in a classroom before they try driving on the roads, the drivers learn by watching the task being both performed and explained simultaneously, and they then perform it for themselves.

Shadowing

Shadowing involves following a user for a period, such as one or two days, to find out what a particular job entails. This is a powerful way to understand a specific user role. When shadowing, we can ask for explanations of aspects such as how the work is done, the information used, or the workflow sequence, so it is a good way of clarifying what the individual actually does to perform the role. It can also be very helpful to uncover some of the taken-for-granted aspects of the work. The longer the analyst spends shadowing a user, the greater the opportunity to build rapport and the better chance there is of capturing the additional details that may not be elicited during a single 45-minute interview. Shadowing key staff is a useful approach during the requirements definition work, since it provides a visual context for processes described during interviews or workshops.

Ethnographic studies

Ethnographic study is often beyond the budget of most business analysis projects but could yield high returns if conducted. It is derived from the discipline of anthropology and involves spending an extended period of time – from a few weeks up to several months – in the target environment. This approach enables the analyst to gain a thorough understanding of the business system as, in a short space of time, the business community becomes used to the analyst’s presence and behaves more naturally and authentically. The main value gained from ethnography is an appreciation of intangible aspects such as the organisational culture in which any proposed change must be embedded, including recognising where both formal and informal power and influences reside. This approach can also be very useful when analysing complex business systems, for example, where the staff members are highly expert in conducting their work and the business rules are difficult to assimilate. In this situation, extended interaction with the experts as they perform their decision-making can be invaluable in acquiring sufficient understanding of the work.

WORKSHOPS

Workshops provide an excellent collaborative forum in which issues can be discussed, conflicts resolved and requirements elicited. They are also a useful forum for carrying out other activities, such as compiling process models, understanding data requirements, eliciting critical success factors and key performance indicators or analysing the quality of a requirements set before they are formally documented. This last aspect is explored further in Chapter 10. Given the various reasons for running workshops, they may be used at many different points during the project. Workshops are especially valuable when time and budgets are tightly constrained and several viewpoints need to be canvassed.

Advantages and disadvantages of workshops

The advantages gained from using workshops includes the ability to:

- Gain a broad view of the area under investigation: having a group of stakeholders in one room will allow the analyst to gain a more complete understanding of the issues and problems.

- Increase speed and productivity: it is less time-consuming to have one extended meeting with a group of people than interviewing them one-by-one.

- Obtain buy-in and acceptance for the project: when stakeholders are involved in such collaboration, not only will they be more open to any business changes or features that result but they are more likely to be champions of the change.

- Gain a consensus view or group agreement: if all the stakeholders are involved in the decision-making process there is a greater chance that they will take ownership of the results. If two or more stakeholders have different viewpoints at the outset, there is a better chance of helping them move to an agreement in a well-facilitated workshop, as long as they feel that their concerns and views have been listened to respectfully.

Although workshops are extremely valuable, there are some disadvantages to using them including:

- Workshops can be time-consuming to organise. For example it is not always easy to get all the necessary people together at the same time.

- If the workshop is not carefully facilitated, it may happen that a forceful participant will dominate the discussion. In extreme cases, such a participant may be able to impose a decision because the other members of the group feel disempowered and unable to raise their objections.

- It can be difficult to ensure that the participants have the required level of authority – which sometimes means that decisions are reversed after the workshop has ended.

Gaining the advantages, and avoiding the disadvantages, is only possible if a workshop is well organised and run; the means of achieving this is discussed in the rest of this section.

Preparing for the workshop

The success or failure of a workshop session depends in large part upon the preparatory work done by its facilitator and its business sponsor for the workshop. They should spend time before the event planning the following areas:

- The objective of the workshop: this has to be an objective that can be achieved within the time constraints of the workshop. If this is a sizeable objective the duration of the workshop will need to reflect this, possibly running to several days. In this case, the objective should be broken into sub-objectives, each of which is the subject of an individual workshop session. For example, a two-day workshop may be broken into four sessions, each of which is focused upon a particular sub-objective.

- The people to be invited to participate in the workshop: it is important that all stakeholders interested in the objective should be invited to attend or be represented. It is the facilitator’s responsibility to ensure that all stakeholders are able to contribute, which may mean performing many of the key tasks by using breakout groups or other techniques, and reporting back to a plenary session to collate the individual results. It can also be useful to consider in advance, the personalities, concerns and viewpoints of those to be invited to the workshop.

- The structure of the workshop and the techniques to be used: these need to be geared towards achieving the defined objective and should take into account the nature of the group, the needs of the attendees and their preferred participation style. For example, a standard brainstorming session may not work very well with a group of people who have never met before and some attendees may prefer to work in smaller groups.

- Arranging a suitable venue: it is important to ensure that the venue provides an environment for focused participation. This may be within the organisation’s premises but it is sometimes useful to use a neutral venue, particularly if the issues to be discussed are contentious or there is a danger that a participant could be interrupted by a colleague or manager who wants to call them away.

Facilitating the workshop

The workshop should start by discussing the objective and endeavouring to secure the participants’ buy-in. Where difficulties are anticipated, it may be useful to invite a senior manager or the project sponsor to open the workshop in order to define some ground rules and set the expectations for behaviour. This also helps to demonstrate a commitment to the process underway. During the workshop, the facilitator needs to ensure that the issues are discussed, views are aired and progress is made towards achieving the stated objective. The discussion may range widely but the facilitator needs to ensure that it does not go completely off the track and that everyone has an opportunity to express his or her concerns and opinions.

A record needs to be kept of the key points emerging from the discussion. This is often done by the facilitator keeping a record on a flipchart, but it is better practice to appoint someone else to take the role of scribe during the workshop. The presence of a scribe allows the facilitator to concentrate fully on the process and the attendees, watching non-verbal behaviour to identify members of the group who may be feeling unhappy or unable to make their points. If the facilitator is spending a lot of time writing or drawing, such cues can be easily missed.

At the end of the workshop, the facilitator needs to summarise the key points and actions. Each action should be assigned to an owner and allocated a timescale for completion.

Techniques

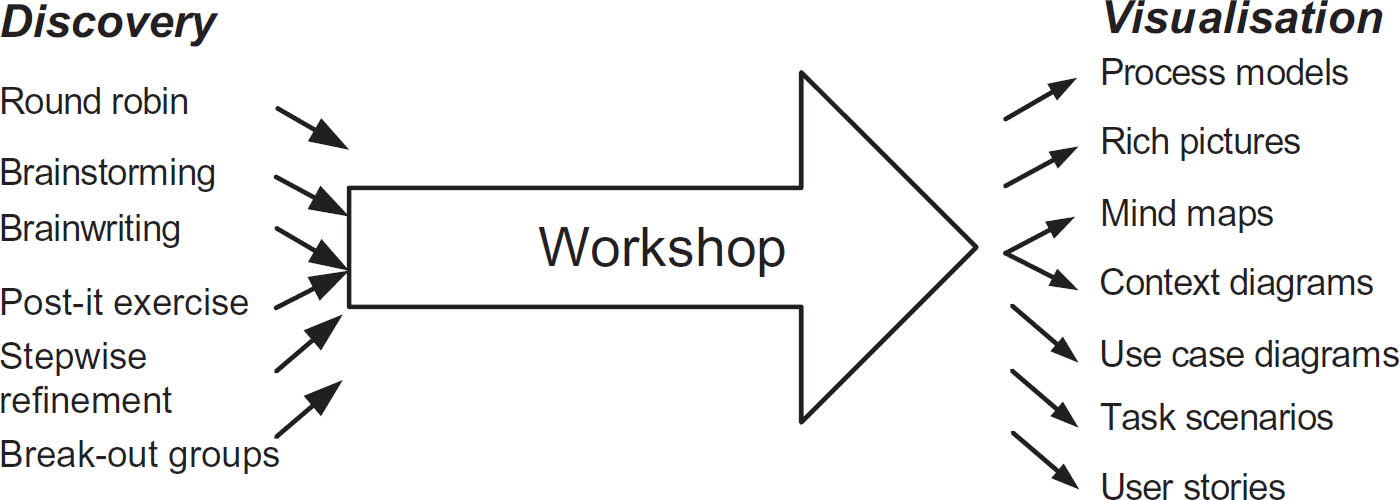

There are two main categories of technique required for a workshop: techniques for discovery and techniques for visualisation.

Discovery techniques are those that help the facilitator to elicit information and views from the participants. It is vital that the facilitator considers which technique would be most suitable for a particular situation and group of participants. Examples of useful techniques (shown in Figure 5.3) are:

Figure 5.3 Workshop techniques

- Brainstorming (sometimes known as idea storming), where the participants are asked to call out ideas about a given item, all of which are written on a flipchart or whiteboard. It is important that all of the suggestions can be seen by everyone taking part as this allows the participants to build on each other’s ideas. Any evaluation of the ideas is suspended until everyone has finished making suggestions.

- Round robin discussions where the workshop participants are asked for their ideas in turn. This can be very useful to encourage participation from those who do not like brainstorming because they are uncomfortable when required to shout out ideas. Round robin discussions provide everyone with an opportunity to speak without fear of interruption or being ignored.

- Brainwriting which has similarities with brainstorming but requires participants to write down ideas. Each person writes an idea on a sheet of paper and then puts it in the middle of the table. Everyone then takes another sheet with an idea already written on it, writes down another idea and then returns the paper to the centre. This continues until there are no more ideas being generated. This approach is useful because it overcomes the problem of ‘shouting out’ while still enabling everyone to build on the ideas of the other workshop attendees.

- Sticky (post-it) note exercises also involve writing down ideas but in this case, the participants work individually or in pairs. Each individual or pair writes down their suggestions – one per sticky note – and, once everyone has stopped writing, displays them to the group, usually by sticking them on a wall or board. Once all of the suggestions have been displayed, those that are similar are grouped together and broader themes are developed.

- Stepwise refinement is where we take a statement or idea and keep asking ‘why?, why?’ to every answer until we think we’ve got to the heart of a problem, idea or situation.

- Smaller ‘break-out’ or ‘syndicate’ groups, where specific aspects are considered and then reported back to the larger group. This is a powerful way to manage a larger workshop, particularly where there is a range of skills and knowledge. It can also be useful for each break-out group to have its own sub-facilitator.

Many visualisation techniques are suitable for use in a workshop. Visual approaches are quick to understand and to explain, and they help workshop participants to access the information being captured. Several useful pictorial or diagrammatic techniques are explored during the course of this book and include process models, data models, use case diagrams, rich pictures and mind maps; some of these are discussed later in this chapter. These techniques help the business users to visualise the area under discussion. Text-based lists may also be required to keep records of suggestions, agreed action points or issues for further discussion.

Another approach is to structure discussions and capture the outcomes using recognised organisational analysis techniques. For example, if the workshop is concerned with the implementation of the business strategy, a higher-level approach, such as critical success factor (CSF) analysis can be employed. This could begin by agreeing the critical success factors for the part of the organisation under discussion, developing the associated key performance indicators (KPIs) and their associated targets, and then considering the information requirements needed to monitor the achievement of the CSFs and KPIs. This can then lead to the definition of more detailed requirements in areas such as data capture and management reporting.

Following the workshop

After the workshop any key points and actions are written up and sent to the relevant participants and stakeholders. This should be done as quickly as possible as this will help to keep up the momentum and highlight the need for quick action.

Hothouse workshop

A hothouse workshop is a specific type of workshop that applies Lean and Agile principles to a business problem. In Agile environments a project, or phase of a project, may be initiated by a hothouse workshop, bringing the business and development teams together to solve business problems and using prototypes to define the functionality and scope of the solution. The business participants are ideally at executive level. This idea derives from the work of James Martin at IBM in the 1980s, when a Joint Requirements Planning (JRP) workshop brought senior executives and analysts together to define functionality, scope and timeframes for new developments. Hothouses combine this JRP approach with Lean techniques. As its name suggests, it is a very intense experience, often with participants working into the night, to produce prototype models of how the new solution might look. Hothouses typically take place over 2–3 days and are primarily for innovation projects rather than simple administration systems or enhancements to existing systems. The workshop group is typically split into smaller teams who each develop a prototype solution during a series of iterations. At the end of each iteration, the output is reviewed and feedback given which is used during the next iteration and so on. The hothouse may be run as a competition between the groups. Ultimately, the outcome should be a prototype solution to a business problem accompanied by additional analyses of the corresponding metrics, processes, costs and benefits required to enable the delivery of the full solution.

Focus groups

Focus groups tend to be concerned with business and market research. They bring together a group of people with a common interest to discuss a topic. While such a meeting has similarities with a workshop, it is not the same thing. A focus group could be used to understand people’s attitudes to any current shortcomings with the business system, for example, the reason why customers are unhappy with a service, or why the website is failing to turn hits into sales. A focus group may be used to suggest ideas for future developments and directions. A focus group will be used as part of an information-gathering exercise, but the findings will need to be evaluated and assessed against the strategy.

Focus-group participants should represent a sample of the target constituency, whether they be external customers or internal staff gathered from multiple sites and branches. They are given an opportunity to express their opinions and views, and to discuss them. In a focus group, unlike a workshop, there is no intention to form a consensus during the discussion, or for the group to acquire a sense of ownership of any decisions made or solutions identified.

Focus groups can be a cost-effective way of obtaining views and ideas, but are unlikely to offer too much in the way of design, and are not suitable for obtaining quantitative data. As with a workshop, the success of a focus-group session depends largely upon the skill of the facilitator in allowing all members to express their thoughts and opinions, and to drill down into whatever may be behind any strong feelings provided as feedback or suggestions.

SCENARIOS

Scenario analysis is essentially telling the story of a task or transaction. Scenarios are useful when analysing or redesigning business processes as they help both the staff member and the analyst to work through the steps required of a business process or system. This will enable them to think through and visualise the steps more clearly. A scenario description will include the business event that triggers the transaction, the set of actions that have to be completed in order to achieve a successful outcome and other aspects such as the actor responsible for carrying out the task, the preconditions and the postconditions. The preconditions are the characteristics of the business or state of the IT system that must be true for the scenario to begin. Postconditions are the characteristics that must be true following the conclusion of the scenario.

One of the key strengths of scenarios is that they provide a framework for discovering the exceptions that require alternative paths to be followed when carrying out the task. The transition from each step to the next provides an opportunity to analyse what else might happen or be true. This analysis often uncovers additional information or tacit knowledge. For these reasons scenarios are extremely useful in requirements elicitation and analysis.

Advantages and disadvantages of scenarios

Scenarios offer significant advantages to the analyst:

- They require the user to include each step and the transitions between the steps, and as a result remove the opportunity for omissions.

- The step-by-step development approach helps ensure that there are no taken-for-granted elements and the problem of tacit knowledge is addressed.

- They are developed using a ‘top-down’ approach, starting with an overview scenario and then refining this with further detail. This helps the business user visualise all possible situations and removes uncertainty.

- A workshop group refining a scenario will identify those paths that do not suit the corporate culture, or that are not congruent with any community of practice involved.

- They provide a basis for developing prototypes.

- They provide a tool for preparing test scripts.

The disadvantages of scenarios are that they can be time-consuming to develop and some scenarios can become very complex, particularly where there are several alternative paths. Where this is the case, you will find it easier to analyse the scenarios if each of the alternative paths is considered as a separate scenario.

Figure 5.4 shows an overview approach to developing scenarios and includes the following steps:

- Identify the task or interaction to be modelled as a scenario and the trigger, or event, that causes that interaction to take place.

- Identify the steps that will be carried out during the usual progress of the interaction, and the flow of these steps.

- Define the control conditions; the conditions that must be met in order to move from one step to the next, following the typical sequence of steps.

- Identify the alternative paths that would be required to handle the situations where the control conditions are not met.

Figure 5.4 Process for developing scenarios (Reproduced by permission of Assist Knowledge Development Ltd)

This approach establishes a default path for the scenario that assumes no complications and everything running as expected. This path is often known as the main success scenario, or sometimes, the ‘happy day’ scenario. Scenarios are powerful when eliciting information, because they break down each of the default steps to ask the questions ‘What needs to be true to continue with this path?’ and ‘At this point, what might happen instead?’ Once the alternatives have been uncovered the analyst can then ask the question ‘What should we do if this happens or if this is true?’

Consider an example scenario where a customer wishes to place an order via the telephone.

The precondition might be that for the process to happen the sales clerk is already logged in to the sales system. The default steps for the telesales clerk could then be:

- enter customer reference number;

- confirm customer details;

- record order items;

- accept payment;

- advise customer of delivery date.

In order for this scenario to flow in the sequence shown, the control conditions to go from step (i) to step (ii), step (ii) to step (iii), and so on must be true. For example, the order items recorded in step (iii) must be in available for step (iv) to take place. However, if there were insufficient stock then the next step to be followed would not be step (iv) but an alternative step. There may be several possible actions to be taken following this alternative step, such as:

- delay an order fulfilment until stock arrives;

- allocate a substitute item;

- send an order and the customer’s delivery details directly to the supplier.

At the (successful) conclusion of the process the postcondition might be: The customer order has been recorded, stock levels have been adjusted and payment has been received.

All of the possibilities should be explored, and documented as alternative paths; these are termed ‘extensions’ to the default scenario. This process helps to ensure that all possible situations and exceptions are anticipated, and so help satisfy the law of requisite variety.

The example scenario above is described in a generic, abstract manner and some users may find this approach difficult to apply to the reality of their work. Another possible approach is known as a ‘concrete’ scenario where a specific narrative or story is developed and then tested against the requirements already identified to find the gaps.

Here is an example of a concrete scenario for a vehicle parts system:

Turpin Coaches calls with an urgent request for 500 Type 2 gaskets. They are a highly valued – and valuable – customer. They tell the clerk that if we cannot satisfy them, they must go elsewhere. The stock records show that there are 150 Type 2 gaskets available. Four hundred were allocated to ZED just 30 minutes previously. Their order will not be processed for another 2 hours. The clerk wishes to amend the ZED order.

Using this concrete scenario, we can see that there is a possible extension in that an order may be prioritised and amended, giving rise to alternative paths through the ‘take order’ scenario. This will require the analyst to record additional requirements to those reflected in the ‘happy day’ such as the ability to prioritise orders and to amend orders already accepted. Concrete scenarios such as this example are extremely useful in helping to uncover where all the possible extensions lie and can be used during one-to-one discussions or workshops. It can be helpful for the analyst to present a prepared ‘happy day’ scenario which is then used as the basis for a discussion. An approach that helps encourage the business stakeholders to contribute wholeheartedly to this process involves placing them in break-out groups with the instruction to produce a concrete scenario that will break the ‘happy day’ path. Experience shows that this instruction sharpens their creativity and produces many valid extensions. All extensions, and resultant requirements, that are uncovered are then added to the analysis documentation.

Documenting scenarios

A popular way of documenting scenario descriptions is to develop use case descriptions to support use case diagrams. This technique is part of the Unified Modeling Language (UML) and is a textual method. However, there are a number of graphical methods for documenting a scenario, such as storyboards, activity diagrams, task models and decision tree diagrams.

USER ANALYSIS

It will be evident from the description of scenario modelling that it is important to understand who the actual users of the proposed system are likely to be and this is also true of prototyping, which we discuss next. A starting point for understanding these users is to identify them and give them generic titles, like ‘customer’, ‘supplier’ or ‘regulator’. (There is clearly a relationship here with stakeholder analysis, which is discussed in Chapter 6.)

However, sometimes these generic titles do not tell us enough about the business users for us to envisage how and why they might want to use an information system. ‘Customer’, for example, is a very broad term that may not capture the different sets of characteristics displayed by the actual customers of an organisation. A good way of understanding customers is to create ‘personas’ for them. For example, for a banking system, we might speculate about three typical customers:

George

George is a man in his mid-70s who has used the bank for 50 years. He is not particularly familiar with computers, which he mainly uses for email to keep in touch with his grandchildren in Australia. He prefers face-to-face contact with the bank to using its online services, though he might be enticed to use these if they could be made intuitive enough.

Emma

Emma is a professional woman in her thirties who combines a fairly high-pressure job with looking after two small children. She is very conversant with computers and prefers to do her banking in spare moments or late in the evening and rarely, if ever, visits a physical bank branch.

David

David is a high-worth businessman who makes extensive use of the bank’s wealth management services. He is extremely busy but nevertheless likes to have a personal relationship with his financial advisers. He demands a high standard of service.

Although these personas are archetypes, they nevertheless help us to envisage why and how these different customers might want to access the bank’s services and to design processes and services that are suitable for them. Personas can also be useful when analysing the users of the business system who have particular accessibility requirements. For example, we may identify a persona that represents customers who have a specific disability that we need to understand in order to enable access to the available business services.

PROTOTYPING

Prototyping is an important technique for eliciting, analysing, demonstrating and validating requirements. Analysts often complain that the business users do not know what they want, and that as a result it is difficult to define the requirements. However, it can be very difficult for anyone to envisage requirements for the future without having a sense of what is possible. It is much easier to review a suggested solution and identify where there are errors or problems. If business users are unclear about their requirements, prototypes can help them visualise the new system and provide insight into possible requirements. Using a prototype often releases the blocks to thinking, and can result in greater understanding and clarity. Prototypes also offer a way of demonstrating how the new processes or system might work and provide a concrete basis for evaluation and discussion. Agile software development approaches, such as DSDM and Scrum, use evolutionary prototyping as an integral part of their development lifecycle.

Prototyping involves building simulations of a process or system in order to review them with the users to increase understanding about the requirements. There is a range of approaches to building prototypes. They may be built using the organisation’s system development environment so that they exactly mirror the future system. Images of the screens and navigations may be built using presentation software packages such as Microsoft PowerPoint or they may be mock-ups on paper. A quick but effective form of prototyping is to use flipchart sheets, pens and packs of sticky notes and work with the users to develop paper prototypes. This will enable the users to develop screens, identify navigation paths, define the data they must input or refer to, and prepare lists of specified values that they know will apply. This approach can also be used to develop prototypes of a business process.

There is a strong link between scenarios and prototyping because scenarios can be used as the basis for developing prototypes. As well as confirming requirements, prototyping can often help the users to identify some that they had not considered previously.

Advantages and disadvantages of prototyping

Prototypes are useful for a variety of reasons including:

- to clarify any uncertainty on the part of the analysts and confirm to the user that we have understood what they asked for;

- to help the user identify new requirements as they gain an understanding of what the system will be able to do to support their jobs;

- to demonstrate the look and feel of the proposed system and elicit usability requirements;

- to validate the system requirements and identify any errors;

- to provide a means of assessing the navigation paths and system performance.

Prototyping has a number of hazards, most of which can be avoided by setting clear objectives for the prototyping exercise and managing the stakeholders’ expectations. The hazards include:

- The prototyping cycle can spin out of control with endless iterations taking place.

- If the purpose of the exercise has not been explained clearly, the users may think that when they are happy with the mock-up, the system is now complete and ready for use.

- User expectations can be raised unnecessarily by failing to mimic the final appearance of the system, or its performance; a system that is on a stand-alone machine with six dummy data records to search will be more responsive than a machine that is sharing resources with a thousand other machines on a national network, and has several million records to access. If there is likely to be a delay in the real response time, it is important that you build that into the prototype.

In an Agile software development environment, prototyping sessions are used to elicit and analyse requirements, and to construct and test working functionality. The development work is conducted iteratively, with each iteration using the concept of a timebox or sprint, typically a predefined number of weeks, within which certain functionality is delivered. During the timebox, the selected requirements for that delivery will be validated, coded, tested and released. Contingency is provided by the prioritisation of the requirements, whereby some are designated at a lower level of priority and may be postponed to a later timebox if necessary. In this approach, the tension between time and quality is resolved in favour of time but, because Agile encourages iterative development, the quality – i.e. the scope of functionality – is merely postponed, not sacrificed. The prototyping approach allows the business to receive the most critical pieces of functionality when it needs it, and the less urgent functionality will be delivered in future iterations.

QUANTITATIVE APPROACHES

Quantitative approaches are used to obtain data that is needed to quantify the information that has been provided during interviews, workshops or other qualitative techniques. Examples of the quantitative data we need could be the following: we might want to know the number of workers who use a particular system, the number of complaints received during a set period or the number of orders processed each day.

Surveys or questionnaires

Surveys can be useful if we need to get a limited amount of information from a lot of people and interviewing them individually or running a series of workshops would not be practical or cost-effective. However, surveys are difficult to design and this has to be done with care in order to have any possibility of success.

The exact design of a survey depends upon its purpose but there are three main areas to consider: the heading, classification and data sections.

Heading section

This is where the purpose of the survey is explained and where instructions for returning it are given. It is very important that the heading section sets out clearly the rationale for the survey, the instructions for its return and, where appropriate, any incentive for completing it. A well-formed heading section will help the respondent to understand why the information is needed, and as a result will significantly increase the volumes that are returned.

Classification section

This is where the details about the respondent are captured. This data provides the basis for categorising the respondents using predefined analysis criteria, like age, gender or length of service. Sometimes, surveys are anonymous in that they do not require identification information about respondents. If this is the case – perhaps because some controversial questions are included – you must make sure that the respondents cannot be identified by other means, or confidence in the process will be lost and you will be unlikely to have a truthful response, if you receive one at all. For example, sometimes asking for data such as job role, age and gender would enable the identification of a respondent.

Data section

This is where the main body of questions is posed. It is vital to think carefully about the phrasing of the questions. They must be unambiguous and, ideally, allow for straightforward answers such as ‘yes/no’, ‘agree/neutral/disagree’ or ‘excellent/satisfactory/inadequate’. It is always better to structure the questions, where possible, so that the same range of answers is the same for each group of questions. It is also important that every set of potential responses is thought through carefully using the MECE approach. MECE stands for ‘mutually exclusive, completely exhaustive’ and involves checking each set of defined, alternative responses to make sure that only one would apply to each respondent and that they cover every situation.

It is important to design surveys carefully if we are to extract meaningful data from the results. We want to be able to build a summary of the responses, observe patterns and trends, and draw relevant conclusions; online survey products are often helpful in supporting this analysis. However, for the conclusions to be meaningful, the survey must provide clear, unambiguous questions and well-defined responses so that the data can be collated and analysed properly. A frequent error used in surveys involves framing questions that are ambiguous. For example, if the question ‘Have you used our website recently?’ was posed and the response was ‘No’, what would that mean? Does it mean that the respondent:

- Is not interested in our products and services and hence has not visited our website?

- Did not know we had a website?

- Is not IT-literate and hence has never used this or any other website?

- Last used the website six months ago and does not consider that ‘recently’?

In this example, the term ‘recently’ is ambiguous and needs to be quantified. Alternatively, the question could be rephrased to ask when the website was last used, and the responses should offer specific time periods that align with the MECE approach.

The key drawback with using surveys is that people will find it difficult to find the time to complete a survey unless it is a topic of interest of significance to them. So, we have to try to clarify the reasons why the survey exists and why their assistance is needed. In some situations, a ‘prize’ or other type of reward may be offered as an inducement to complete the survey. Ultimately, though, it can be very difficult to obtain the desired number of responses and that needs to be factored into the design when adopting a survey approach.

Special purpose records

Special purpose records are data-gathering forms used by the analyst; the format is usually decided by the analyst and they are not company records. They can be completed either by the analyst during an observation session or given to the business users to complete over a period of time.

If the area under investigation were customer services, the analyst may spend a period of time in the department shadowing one of the staff and compiling a special purpose record in order to record the number of customer approaches per day, and classify them – perhaps using a five-bar gate notation – according to whether they are complaints, queries or returned goods. They may record the nature of customer calls, their duration, how long it takes to retrieve the data needed to answer the query. Such information could help the analyst understand the problems with the business process and where there is scope for improvement.

Another approach is to give the form to the business users to complete as they perform the task. For example, they could keep a five-bar gate record about how often they need to transfer telephone calls – this could provide the analyst with information about the problems with the business process.

There are difficulties with getting people to keep this form of record, chief of which is that it is easy to forget to record each occurrence. So, if getting people to keep special purpose records is to be useful, two important criteria have to satisfied:

- The people undertaking the recording must be induced to ‘buy-in’ to the exercise. This may be by persuading them of the need or benefits, however, another possibility is that they are instructed to do this by their manager.

- The survey must be realistic about what people can reasonably be expected to record.

Notwithstanding this, it can still be useful sometimes to get people to keep such records as they help avoid the problems associated with observation and it can be an effective use of the analyst’s time.

Activity sampling

This is a further quantitative form of observation and can be used when it is necessary to know how people divide their work time among a range of activities. For example, how much time is spent on the telephone? How much time spent on reconciling payments? How much time on sorting out complaints?

One way to find out how people spend their time would be to get them to complete a special-purpose record but sometimes the results need to have a guaranteed level of accuracy, for example if they are to be used to build a business case. In situations where accuracy is important, activity sampling may be used in preference to observation or special-purpose records. An activity sampling exercise is carried out in five steps:

- Identify the activities to be recorded. This list should include a ‘not working’ activity as this covers breaks or times away from the desk. It might also include a ‘not-related’ task, such as first aid or health and safety officer duties.

- Decide on the frequency and timings, i.e. when and how often you will record the activities being undertaken.

- Visit the study group at the times decided upon and record what each group member is doing.

- Record the results.

- After a set period, analyse the results.

The results from an activity sampling exercise provide quantifiable data about the number of times an activity is carried out per day by the group studied. By analysing that figure against other data, such as the total amount of time available, we are able to calculate the total length of time spent on that activity and the average time one occurrence of the activity will take. This information can be useful when developing business cases and evaluating proposed solutions. Also, it will raise other questions such as whether the average time is reasonable for this task or whether it indicates a problem somewhere else in the process.

Document analysis

Document analysis involves reviewing samples of source documents to uncover information about an organisation, process or system.

For each document, we might analyse:

- How is the document completed?

- Who completes the document?

- Are there any validations or controls on the document?

- Who uses the completed document?

- When is the document used?

- How many are used or produced?

- How long is the document retained by the organisation, and in what form?

- What are the details of the information shown on the document?

- Where is the data or information obtained?

- Are other names used in the organisation for any of the items of data?

- Are all the data items on the document still needed, or are any redundant?

- Is there other data that is not entered on the document, but would be useful for this process?

Document analysis is useful to supplement other techniques such as interviewing, workshops and observation. For example, analysing the origin and usage of a document can prove very enlightening when investigating a process. Samples of completed documents or system printouts also help to clarify the key items of data used to carry out the work and can prove an excellent basis for modelling data (see Chapter 12).

SUITABILITY OF TECHNIQUES

Some of the techniques described in this chapter are suitable for general investigation of the problem situation and others more for eliciting requirements for the new system. Of those suitable for requirements, some are more suitable for a waterfall approach and others geared more towards Agile developments. Some techniques are suitable in all situations. Table 5.1 gives a guide to the suitability of these techniques for the different situations.

DOCUMENTING THE CURRENT SITUATION

While the investigation of the current situation is going on, the analyst will need to record the findings, in order to understand the range of issues and the business needs. Meeting reports should be produced for each interview and workshop so that they can be agreed with the participants. It is also helpful to use diagrams to document the business situation. This section suggests five diagrammatic techniques that help the analyst understand the information that has been obtained and find the root cause of any problems.

Rich pictures

The rich picture technique is one of the few that provide an overview of an entire business situation. Whereas modelling approaches such as data or process modelling provide a clear representation of a specific aspect of a business system, rich pictures show all aspects. The technique does not have a fixed notation, but allows the analyst to use any symbols or notation that are relevant and useful. For this reason the rich picture can show the human characteristics of the business situation and can reflect intangible areas such as the culture of the organisation. Many problems in the current business system may have originated with the people performing the tasks rather than being caused by poor process design or inadequate IT systems. There could be differing viewpoints, misunderstandings, stress from too many tasks, personal differences with co-workers, dissatisfaction with management or frustration at inadequate resources. Any of these factors could impair the performance of a task, but the traditional analysis models would not be able to record them. A rich picture allows the analyst to document all of the human and cultural aspects as well as information flows and information usage. The unstructured nature of the technique allows the analyst to ‘brain dump’ the information in a simple, pictorial representation. Its strength is that the process of building the rich picture helps the analyst to form a mental map of the situation and see connections between different issues. The rich picture can also be enriched further as more information about the situation comes to light. Figure 5.5 shows an example of a rich picture for a business system called Rake’s Refreshments.

Table 5.1 Suitability of techniques for different situations

Figure 5.5 Example of a rich picture (Reproduced by permission of Assist Knowledge Development Ltd)

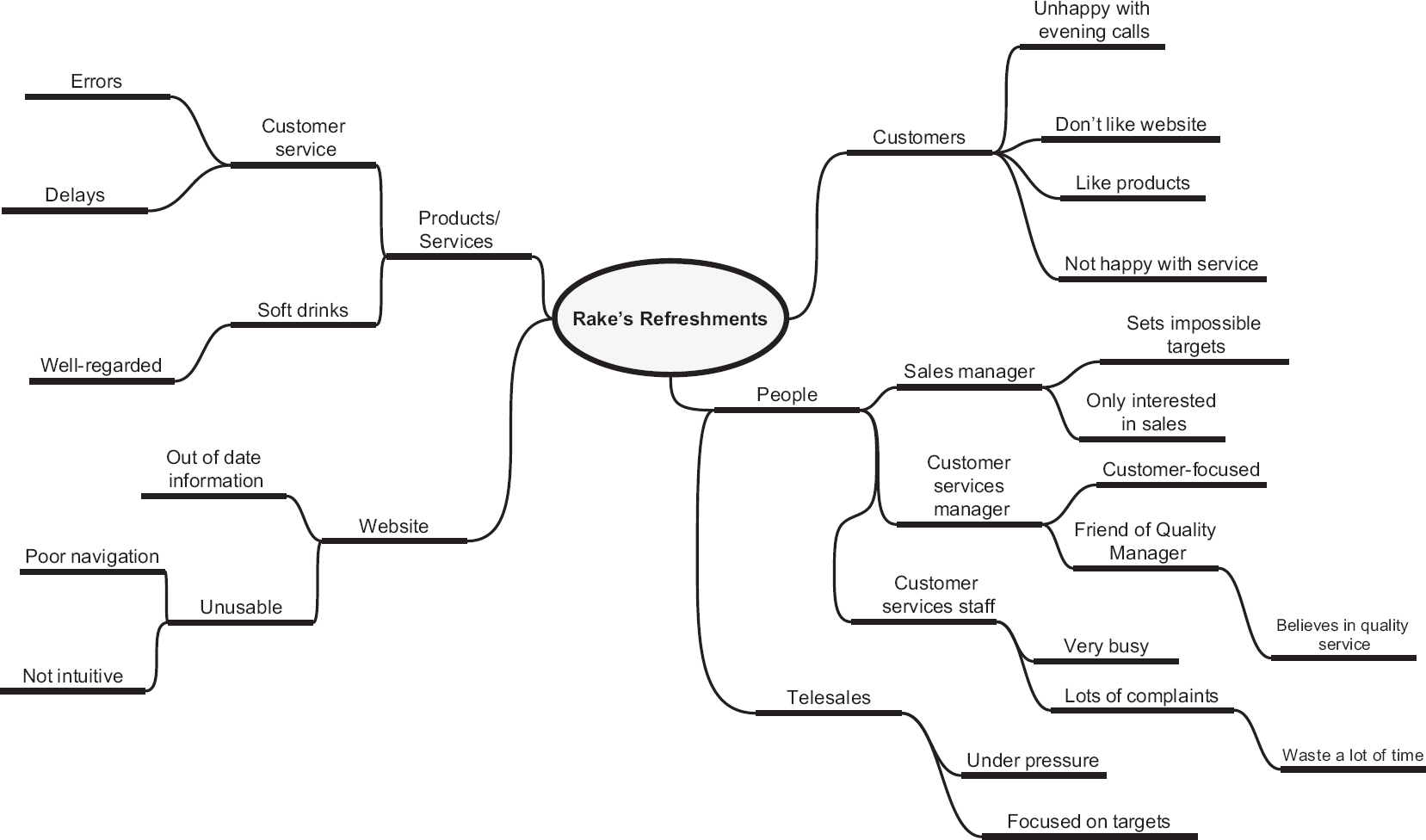

Mind maps

Mind maps are a useful tool for summarising a lot of information in a simple visual form that is structured to highlight connections between different ideas and topics. They provide a means of organising information while, in a similar vein to rich pictures, representing all of the issues that have been uncovered about the situation. The business system or problem under consideration is drawn at the centre of the diagram with the main elements shown as first level of branches radiating from the central point. Each of these branches is labelled to indicate the nature of the particular area or issue; the labels should use as few words as possible, ideally one word. The branches might represent such matters as particular processes, the equipment and systems used, relationships between the staff that do the job and so on. These branches can then support second-level branches that are concerned with more detailed areas for each aspect of the situation. For example, the branch for equipment might show problems with the printing or photocopying equipment and the branch for systems might show the key failings of the IT system. A mind map helps structure the information gathered into a recognisable and manageable set of connections. Mind maps are extremely useful in helping analysts to order their thinking, and they work well both on their own and when used in conjunction with rich pictures. The mind map in Figure 5.6 for Rake’s Refreshments relates to the rich picture shown in Figure 5.5.

Figure 5.6 Example of a mind map (Reproduced by permission of Assist Knowledge Development Ltd)

Business process models

In order to understand fully how a process is carried out, it is helpful to draw a ‘swimlane’ diagram, which shows the tasks in a process, the actors responsible for carrying them out and the process flow. These models are easy to draw and business stakeholders find them accessible, so they provide a good communication tool between the analyst and the business staff. Business process models are also invaluable as a diagnostic aid since they help identify problems such as delays, bottlenecks and duplicate tasks. They are described in greater detail in Chapter 7.

Spaghetti maps

A spaghetti map is a tool to show the movement and interactions of the stakeholders in a particular environment, when performing particular tasks and processes. It is called a spaghetti map simply because as the movements are drawn, the diagram created resembles a plate of spaghetti, with lines crossing back and forth without any apparent formality or design. Spaghetti maps can be drawn up during an observation session, mapping the movements of users across the room to meet different actors or to use equipment such as printers or photocopiers.

Figure 5.7 shows a spaghetti diagram drawn while observing a clerk in the service department of a garage checking in a car for repair and allocating a courtesy car to the customer. Despite having a computer on her desk she still needed to make use of a printer, a photocopier, a filing cabinet and a wall chart in order to perform the task. Their position on the map is similar to their position in the real office. It is easy to see how much of the clerk’s time is taken over the course of a day in accessing these different stations. This diagram represents one person executing one instance of a common task, and makes clear the scope for efficiency gains.

Figure 5.7 Example of a spaghetti map

It is interesting to note that a swimlane diagram would not show the physical movement required for an actor to perform a task, so it would not highlight the potential for improvement. The two diagrams together help identify the scope for improvement in the process.

Fishbone diagrams

One of the major objectives in investigating and modelling a business system is to identify where there are problems and discover their underlying causes. Some of these may be obvious, or the stakeholders may be aware of the root causes of their problems. However, sometimes it is only the symptoms that are highlighted by the stakeholders because the causes have proved difficult to isolate. The fishbone diagram is a problem-analysis technique, designed to help understand the underlying causes of an inefficient process or a business problem. It is similar to a mind map in some ways, but its purpose is strictly diagnostic. The technique was invented by Dr Kaoru Ishikawa (Ishikawa 1985), and the diagrams are sometimes known as Ishikawa diagrams. They are often used in root cause analysis. The name of the problem is documented in a box at the right-hand side of the diagrams. Stretching out from the box towards the left of the page is the backbone of the fish. Radiating up and down from this backbone are spines; the spines suggest possible areas for causes of the problem. A number of approaches may be used when labelling the spines:

- The four Ms: manpower, machines, measures and methods.

- An alternative four Ms: manpower, machines, materials and methods.

- The six Ps: people, place, processes, physical evidence, product/service and performance measures.

- The four Ss: surroundings, suppliers, systems and skills.

These categories help because they list areas that have been found to be the sources of inefficiencies in many business systems. In practice we often consider a range of categories and might combine the most relevant elements from the approaches above, or even define some categories that are particularly relevant to a given project. Data for this analysis can be found from interviews, workshops, activity sampling, observation and special purpose records. The categories to be used on the fishbone diagrams can also provide a structure to a workshop discussion.

As with mind maps, the spines have more detailed elements associated with them. Each category along a spine is examined, and the factors within that category that may be affecting the problem are added to the diagram. The resultant diagram is shaped like a fishbone – hence the name fishbone diagram. An example of a fishbone diagram is shown in Figure 5.8.

Figure 5.8 Example of a fishbone diagram (Reproduced by permission of Assist Knowledge Development Ltd)

Once the diagram has been completed, we can analyse the results by looking for the key causes of problems. These are the items that are listed several times, since they are the ones that are likely to be having a broad impact upon the situation. They should be considered for rapid action in order to help address the issue promptly.

SUMMARY

Any business analysis project will inevitably include investigating business situations in order to clarify the problem to be addressed. To do this effectively, the business analyst needs a toolkit containing a range of investigative and diagrammatic techniques. This toolkit provides the basis for a key competency of a business analyst which is the ability to appreciate when particular techniques are relevant and the ability to apply them effectively.

REFERENCE

Ishikawa, K. (1985) What is Total Quality Control? The Japanese Way. Prentice Hall, Upper Saddle River, NJ.

FURTHER READING

Cadle, J., Paul, D. and Turner, P. (2014). Business Analysis Techniques: 99 essential tools for success, 2nd edn. BCS, Swindon.

Robertson, S. and Robertson, J. (2012) Mastering the Requirements Process, 3rd edn. Addison Wesley, Boston, MA.