INTRODUCTION

This chapter is about four aspects of strategy analysis:

- understanding what strategy is and why it is important, the assumption being that strategy is important;

- exploring some ideas about how strategy is developed;

- implementing strategy;

- working out what all of this means for business analysts.

There is no intention to try to turn you into strategic planners but instead to enable you to understand the process of strategy development, be comfortable with the tools that managers use and be able to use them yourself as you explore how new or different information systems could push forward the activities of the organisation that employs you.

THE CONTEXT FOR STRATEGY

Why do organisations bother about strategy? What advantage do they hope to gain? Let us look at what is happening in the world. Most of us would probably support the idea that business is becoming increasingly unpredictable and changes are more turbulent, with international mergers and acquisitions once again becoming regular features of business life as economies come out of the post-banking crisis recession. The information revolution and the digital economy have caused much of this dramatic change and barriers between previously separate businesses are falling like dominoes. For example, who will be the big financial players in the future? It could be the global banks, retail outlets like Tesco or Walmart, strong brands like Amazon or Virgin. If you are working in the finance sector how do you know where to move next? What are the longer term implications of government shareholdings?

There are some big changes that organisations face and that strategy development tries to moderate:

- There are the changes to the ways that we are employed. There is much more use of part-time and contract employees who may have little long-term loyalty to their employer and who have their own individual career and work/life balance plans. The growth of knowledge-based industries and the continuous change experienced by organisations means that individual employees, consultants or contractors – permanent, full-time or part-time – have become valuable assets. This is more than ever the case as organisations everywhere, in both Government and commercial sectors, flatten their organisation structures, decentralise decision-making and give more freedom to individuals to make decisions, deal with customers and resolve problems. There are no longer jobs for life and attitudes to work have changed. We all now want great job satisfaction, higher rewards, more personal recognition and flexible working environments.

- Society has changed. There is greater freedom of expression and of thought. Freedom of information legislation means that individuals have access to evidence and decisions taken by government that were previously hidden. There is less respect for authority and office unless it has been earned. Our attitudes to change, direction, reorganisation and other people knowing better than we do have shifted and the development and implementation of new strategies need to take this into account.

- Organisations are responding to these changes by doing everything they can to increase their flexibility and responsiveness. This means that they seek to reduce employment costs and without trade unions to apply a brake we see central government and European institutions taking this role.

- The world is full of contradictions. Some of these are:

- Global versus local. Globalisation creates the largest markets ever known and until we have intergalactic businesses this will remain the case! But it also means that the players in a global market can be small. Having a global reach does not mean being the biggest. The scarcity of the product, its brand reputation and its distribution channels make the difference. All the paparazzi know this; one paparazzo, with access to a camera, the right moment and the internet, sells his product across the world in less than a day.

- Centralised versus decentralised organisation structures. Finance may be a central process but prices and discounts are set locally.

- Hard and soft management. Developing strategy is seen as a ‘hard’ discipline like finance and technology but the creativity and change skills that make strategy work are the ‘soft’ skills.

Finally there are two questions. How can anyone create, formulate or build a strategy if the future is inherently unknowable and unpredictable, and how can it be implemented in a coherent way in decentralised structures with delegated authorities and an ever-changing environment? This makes it appear very difficult for a business analyst to understand the nature and permanence – or impermanence – of the business strategies against which IS strategies are to be built. However, as we shall see, through an examination of the nature of strategy and the use of some well-tried tools, effective steps can be taken to deal with this difficulty.

WHAT IS STRATEGY?

The concept of strategy begins in a military context and the word strategy is derived from the Greek word ‘strategia’ which means ‘generalship’. It has a ‘getting ready for battle’ sense to it and the deployment of troops, weapons, aircraft and ships before engagement with the enemy begins. Once the enemy is engaged then battlefield tactics determine the success of the strategy. The transfer of these ideas into business is easy to make, therefore, and we expect to deal with:

- The goal or mission of the business. In strategy terms this is often referred to as the direction.

- The time frame. Strategy is about the long term. The problem here is that it differs widely across industries, with petrochemicals and pharmaceuticals at the really long end and domestic financial services products at the short end.

- The organisation of resources such as finance, skills, assets and technical competence so that the organisation can compete.

- The environment within which the organisation will operate and its markets.

A popular definition appears in Johnson, Scholes and Whittington (2008):

Strategy is the direction and scope of an organisation over the long term, which achieves advantage in a changing environment through its configuration of resources and competences with the aim of fulfilling stakeholder expectations.

However, writers and gurus have offered their own definitions for at least the last 40 years including George Steiner (1979) who did not so much define it as paint a picture of it by saying that strategy is:

- what top management does;

- about direction;

- the process that sets in motion the important actions necessary to achieve these directions;

- what the organisation should be doing.

But finally, Johnson, Scholes and Whittington (2008) provide a helpful definition of the issues to be considered during strategy analysis. These are:

- the long-term direction of an organisation;

- the scope of an organisation’s activities;

- advantage for the organisation over competition;

- strategic fit with the business environment;

- the organisation’s resources and competences;

- the values and expectations of powerful actors.

Strategies exist at different levels in an organisation ranging from corporate strategies at the top level affecting the complete organisation down to the operational strategies for product/services offerings. Typical levels of strategy could be:

- Corporate Strategy that is concerned with the overall purpose and scope of the business. Strategies at this level are influenced by investors, governments and global competition, and by the context set out earlier in this chapter. It is the basis of all other strategies and strategic decisions.

- Business Unit Strategy. Below the corporate level are the strategic business units (SBUs). These are organisational units for which there are distinct external markets that are different from those of other SBUs. SBU strategies address choice of products, pricing, customer satisfaction, and competitive advantage.

- Operational Strategy focuses on the delivery of the corporate and SBU strategies through the effective organisation and development of resources, processes and people.

STRATEGY DEVELOPMENT

This section begins with some fundamental questions: How do I start to develop a strategy? Where does strategy development come from? How do I know what kinds of strategy to develop? There are many different drivers for strategy development and strategy may be formulated in different ways. For example:

- Strategy associated with an individual, often the founder of a business. Examples of founders who set strategy include Mark Zuckerberg and Richard Branson. Where a business is already established but needs a new direction, a new CEO may be brought in to change the strategy in order to move the organisation forward.

- Alternatively, strategy may develop from the experiences and views of internal managers. Groups of managers may meet regularly to review trends in the market and their own business progress; they plan new actions and try them out. Strategy then evolves in an incremental, negotiated way.

- Another possibility is to enable the generation of innovative ideas from within the organisation so that the strategy emerges from the people who do the work.

- It is also possible to formulate strategy by adopting a formal, carefully planned, design process. Some organisations find this to be essential, especially those for which strategy is truly long term.

So far the development of strategy has been considered as a rational, logical and organised process. It often is developed like this, and in this chapter we will consider many of the tools that are used to inform the strategy process. However, another force that may drive strategy formulation is the politics within the organisation. We can view an organisation as a political system that manipulates the formation of strategy through the exercise of power. Different interest groups form around different strategic ideas or issues and compete for resources and the support of stakeholders to achieve the dominance of their ideas. On this basis, strategic direction is not achieved through a universally accepted, rational analysis but through the promotion of specific ideas of the most powerful – and usually highly political – groups. This power comes from five main sources:

- Dependency – departments are dependent on those departments that have control over the organisation’s resources. The power of the human resources (HR) department increases if all new staff requisitions have to be authorised by HR.

- Financial resources – where are the funds to invest in the development of new ideas, products or services? Who has these funds? What financial frameworks constrain or give freedom to different groups?

- Position – where do the actors live in the organisation structure and how does their work affect the organisation’s performance?

- Uniqueness – no other part of the organisation can do what the powerful group does.

- Uncertainty – power resides with people and groups can cope with the unpredictable effects of the environment and protect others from its impact.

Whichever approach is adopted and whatever the internal politics, the development of strategy always needs to incorporate some external analysis, for instance ‘what is happening out there?’, some internal analysis, such as ‘where do we fit in to what’s happening out there?’, plus some consideration of how new strategies could be executed.

Once a strategy has been developed, it is important to provide a written statement of the strategy. This written statement is needed for many reasons:

- it provides a focus for the organisation and enables all parts of it to understand the reasons behind top-level decisions and how each part can contribute to its achievement;

- it provides a framework for a practical allocation of investment and other resources;

- it provides a guide to innovation, where new products, services or systems are needed;

- it enables appropriate performance measures to be put in place that measure the key indicators of our success in achieving the strategy;

- it tells the outside world, especially our outside stakeholders and market analysts, about us and develops the expectations that they hold.

EXTERNAL ENVIRONMENT ANALYSIS

Most organisations face a complex and changing external environment of increasing unpredictability. Let us take as an example a retail electrical and electronics store which faces some or all of the following external changes:

- The state of the national and local economies. Product demand is influenced by local employment and incomes and the cost of credit.

- Product cost. Price competition is high and there is a continuing shift to move manufacturing to lower cost economies with the possible impact on supply and after-sales support.

- Changes in consumer lifestyles and tastes. The high cost of housing leads to a greater incidence of smaller houses and a growth in the supply of flats calling for smaller furniture and kitchen equipment. Streaming films replaces DVD or Blu-ray and streaming music replaces digital downloads.

- Changes in technology. There is a greater demand for smaller devices, flatter screens and multi-purpose devices.

- New marketing approaches with consumers buying over the internet or from catalogue retailers.

With a little thought it would have been possible to identify these kinds of environmental trends but many of the more dramatic changes have come from surprising places. For example, the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 (SOX) was introduced in response to a number of major corporate and accounting scandals, most notably at Enron and Tyco International. Although it was clear that something had to be done, critics have claimed that SOX places US firms at a disadvantage compared to overseas competitors and imposes high additional costs on business. More dramatic and unexpected are the activities of environmental or animal rights campaigners or a sudden change in technology that changes generally accepted business models.

There is a framework to help organisations assess their broad environment. It is the PESTLE analysis – sometimes called a PESTEL or just PEST analysis – but whatever the acronym it is an examination of the political, economic, socio-cultural, technological, legal and environmental issues in the external business environment. Some of the influences which may be identified in these categories are shown below.

Political influences

- The stability of the government or political situation

- Government policies – such as on social welfare

- Trade regulations and tariffs

Economic influences

- Interest rates

- Money supply

- Inflation

- Unemployment

- Disposable income

- Availability and cost of energy

- The internationalisation of business

Taken together these economic factors determine how easy – or not – it is to be profitable because they affect demand.

- Demographics – such as an ageing population in Europe

- Social mobility – will people move to find work or stay unemployed where they are and rely on state support? This may also be seen as a political issue with an enlarged Europe enabling a freer movement of labour across the community

- Lifestyle changes – such as changes in the retirement age and general changes in people’s views about work/life balance

Technological influences

- Technological developments

- Government spending on research, the quality of academic research, the ‘brain drain’

- The focus on technology; demand for invention and innovation

- The pace of technological change, the creation of technology enabled industries

Legal influences

- Legislation about trade practices and competition

- Employment law – employment protection, discrimination etc

- Health and safety legislation

- Company law

- Financial regulation

Environmental influences

- Global warming and climate change

- Animal welfare

- Waste, such as unnecessary packaging

- Environmental protection legislation such as new laws on recycling and waste disposal industries

It is important that we do not view PESTLE analysis as a set of checklists as these are not of themselves useful in making a strategic assessment. The key tasks are to identify those few factors that will really affect the organisation and to develop a real understanding of how they might evolve in the future. In some cases a few issues may be so important that they provide a natural focus. It may also be helpful to get external expert opinion.

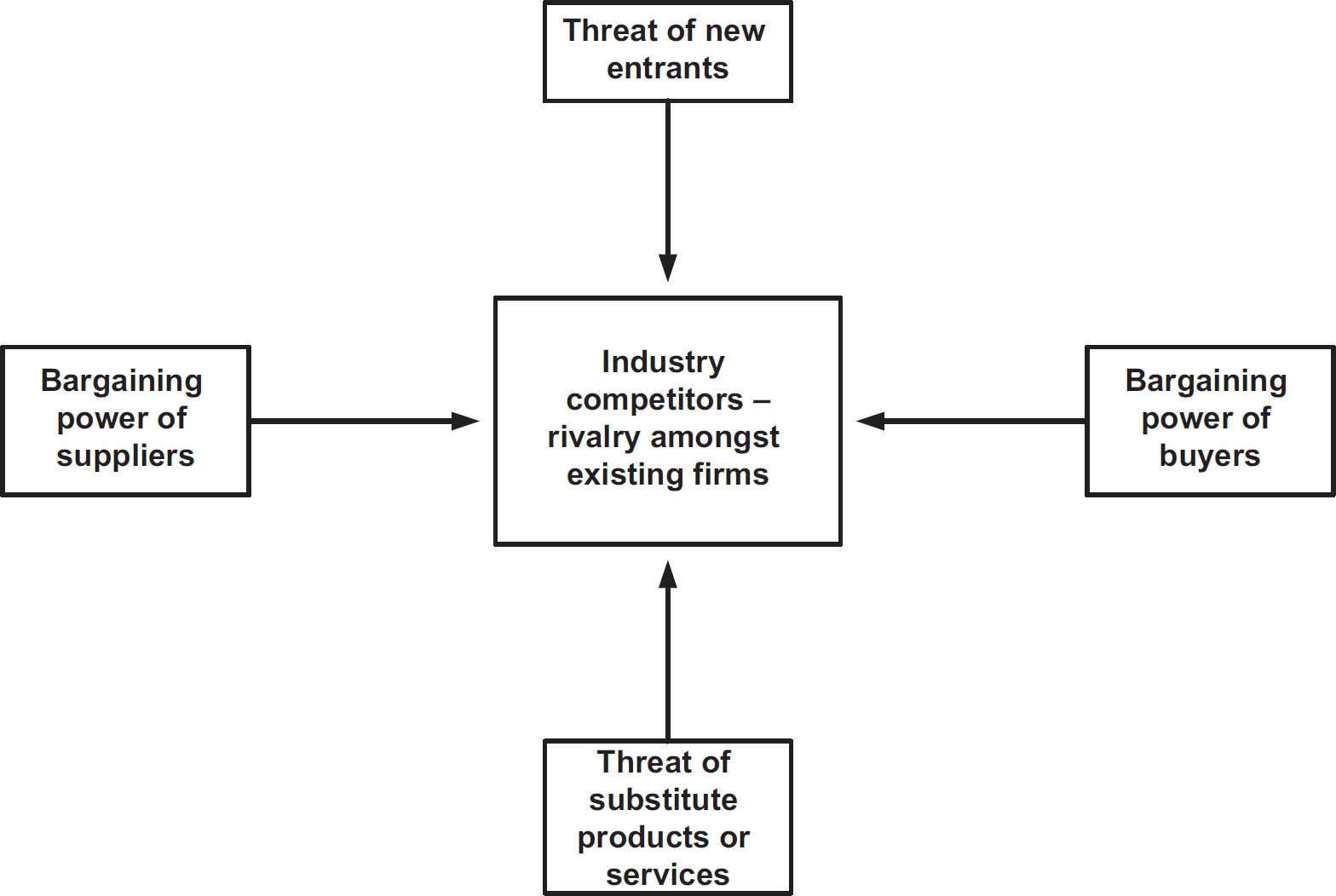

Having examined the external environment we should now consider the competition our organisation faces. Few businesses have no competition, even those in the not-for-profit sector, and most seek to develop and keep a competitive advantage over their rivals. They aim to be different or better in ways that appeal to their customers. An analysis tool that helps to evaluate an industry’s profitability and hence its attractiveness is Michael Porter’s Five Forces model (Porter 1980). This is shown in Figure 3.1 below. In the centre is the competitive battleground where rivals compete and where competitive strategies are developed. Organisations need to understand the nature of their competitive environment. Additionally, they will be in a stronger position if they understand the interplay of the five forces and can develop defences against the threats they pose.

Figure 3.1 Porter’s Five Forces model

New entrants may want to move into the market if it looks attractive and if the barriers to entry are low. Globalisation and deregulation both give new entrants this opportunity but there are barriers to entry that organisations build. These include:

- Economies of scale. This may be difficult to achieve for a new entrant.

- Substantial investment required. A new entrant may have difficulty in obtaining sufficient funds for investment.

- Product differentiation. If existing products and services are seen to have strong identities, which are supported by high expenditure or branding, then new entrants may be deterred from entry.

- Access to distribution channels. Existing distribution channels may be booked by existing suppliers requiring new entrants to find new and different distribution channels.

- The existence of patented processes.

- The need for regulatory approval, for example, in the financial and defence sectors.

Supplier power limits the opportunity for cost reductions when:

- there is a concentration of suppliers and when supplying businesses are bigger than the many customers they supply;

- the costs of switching from one supplier to another are high. This may be because of clauses in supply contracts, interacting IT systems between the organisation and its suppliers, supply logistics or the inability of other suppliers to deliver;

- the supplier brand is powerful, for example, the power of ‘Intel Inside’;

- customers are fragmented so do not have a collective influence.

Customer power – or the bargaining power of buyers as Porter called it – is high when:

- there are many small organisations on the supply side. For example, in the supply of food products to supermarkets;

- alternative sources of supply are available and easy to find;

- the cost of the product or service is high, encouraging the buyer to search out alternatives;

- switching costs are low.

The threat from substitute products is high when:

- product substitution from new technologies is more convenient;

- the need for the product may be replaced by meeting a different need;

- it is possible to decide to ‘do without it’!

All of these forces impact on the competitive battleground in some way. There may also be high competitive rivalry when:

- there are many competing firms;

- buyers can easily switch from one firm to another;

- the market is growing only slowly or not growing at all;

- the industry has high fixed costs and responding to price pressure is difficult;

- products are not well differentiated or are commoditised so there is little brand loyalty;

- the costs of leaving the industry are high.

Porter’s framework is simple to use and understand and it helps to identify the key competitive forces affecting a business. It is widely used in the development of strategies. There are, however, some weaknesses of which the most often mentioned is that government is not treated as the sixth force. Porter’s response is that the role of government is played through each of the five forces – for example, legislation affects entry and rivalry – and so it has not been ignored. There are also views that it is difficult to apply the model to not-for-profit organisations and that since the 1980s the increasing development of international businesses has led to a more complex set of competitive and collaborative relationships. Nonetheless it is widely accepted as a useful analytical tool.

Having used PESTLE and Porter to analyse the external environment, we will have much useful data about the external conditions the organisation may face. However, even with this information, the world springs surprises on organisations from time to time. There is a high level of uncertainty and some different approaches are needed to understand potential future impacts. Scenarios may be used to do this. They look at the medium- and long-term future and, by evaluating possible different futures, prepare the organisation and its managers to deal with them. They begin by identifying the potential high impact and high uncertainty factors in the environment. It is tempting to choose just two scenarios – good and bad – when doing this, but really four or more are needed and they should be plausible and detailed. Next, the future scenarios these factors could construct are considered, possibly by looking at the possible steps and asking ‘what if?’ questions. In doing this we are concerned with predetermined events such as predicted demographic changes, key uncertainties – often political and economic, including regulation and world trade – and driving forces such as technology and education. This information comes from the PESTLE analysis.

INTERNAL ENVIRONMENT ANALYSIS

The external environment creates opportunities and threats and can give an ‘outside/in’ stimulus to the development of strategy. Successful strategies depend on something else as well; it is the capability of the organisation to perform. Can an organisation continue to change its capability so that it constantly fits the environment in which it operates? Can it always be innovative in the way it exploits this capability? Two techniques that help in the analysis of the internal organisation are discussed in this section – the resource audit and portfolio analysis using the Boston Matrix. All of this begins, however, with an understanding of the current business positioning, and for this we will consider the MOST analysis technique. MOST analysis examines the current mission, objectives, strategy and tactics and considers whether or not these are clearly defined and supported within the organisation. We can define the MOST terms as follows:

- Mission A statement declaring what business the organisation is in and what it is intending to achieve.

- Objectives The specific goals against which the organisation’s achievements can be measured.

- Strategy The medium to long-term approach that is going to be taken by the organisation in order to achieve the objectives and mission.

- Tactics The detailed means by which the strategy will be executed.

A clear mission driving the organisation forward, a set of measurable objectives and a coherent strategy will enhance the capability of the organisation and be a source of strength. On the other hand, where there is a lack of direction, unclear objectives and an ill-defined strategy the internal capability is less effective and we have a source of weakness. When considering the MOST analysis as a means of identifying strengths and weaknesses, it is useful to think about the following aspects:

- Is the MOST clearly defined? For example, are the objectives well-formed and SMART (Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant and Time framed)?

- Is there congruence between elements of the SWOT (strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, threats)(see below)? For example, is the strategy aligned with the objectives?

- Has the MOST been communicated to the managers and staff of the organisation?

Reflecting on core competences starts the strategy process from inside the organisation so it is an ‘inside/out’ approach based on the belief that competitiveness comes from an ability to create new and unexpected products and services from a set of core competences. The Resource Audit can help us to identify core competences or may highlight where there is a lack of competence that could undermine any competitive moves. There are five key areas to examine, the first three being sets of tangible resource:

- The first area relates to the physical resources that the organisation owns or has access to and includes features such as buildings, plant and equipment, land and so on. These may be modern and cost-effective or old-fashioned, unreliable and incur high maintenance costs.

- Second, there are the financial resources that determine the organisation’s financial stability, capacity to invest in new resources and ability to weather business fluctuations and changes.

- Then, there are the human resources and their expertise, adaptability, commitment, etc.

There are then the intangible resources such as the know-how of the organisation which may include actual patents or trademarks, but this may also be derived from the use made of resources such as information and technology; many organisations hold a large amount of information but it is not available when required or not in a format that can be used easily. Another intangible resource is the reputation of the organisation, for example the brand recognition and the belief that is held about the quality of the brand, and the goodwill – or antipathy – that this produces. An analysis of the organisation’s resources will identify where these provide a source of competence – strengths, or where there is a lack of capability – weaknesses.

The portfolio of business units, each offering their own products and services, may also be a source of strength or weakness for an organisation. Organisations need to review their portfolio on a regular basis in order to take decisions about the resources to be invested into each business unit or even each product or service. Portfolio analysis was developed to address this problem.

The original portfolio matrix – the Boston Box – was developed by the Boston Consulting Group and provides a means of conducting portfolio analysis. A company’s strategic business units (SBUs) – parts of an organisation for which there is a distinct and separate external market – are identified and the relationship between the SBU’s current or future revenue potential is modelled against the current share of the market. The Boston Box uses these two dimensions to enable organisations to categorise their SBUs and their products/services, and thereby consider whether and how much to invest. Put simply as in Figure 3.2, the cows are milked, the dogs are buried, the stars get the gold and the wild cats are carefully examined until they behave themselves or join the dogs and die.

Figure 3.2 The Boston Box

A successful product or SBU starts as a Wild Cat and goes clockwise round the model until it dies or is revitalised as a new product or service or SBU. The Wild Cats (or Problem Children) are unprofitable but are investments for the future; the Stars strengthen their position in a growth industry until they become the big profit earners. The Cash Cows are the mature products or services, in markets with little, if any, growth. The Stars and Cash Cows provide the funding for the other segments of the matrix. The Dogs have low market share in markets with low growth and are often the areas that are removed or allowed to wither away.

SWOT ANALYSIS

The SWOT (strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, threats) analysis is often used to pull together the results of an analysis of the external and internal environments. However, too often it is used as the first analytical tool before enough preparatory analysis has been done. When this approach is adopted the results are usually weak, inconclusive and insufficiently robust to be of much use. A more robust approach is to use the techniques described earlier as they help identify the major factors, both internal and external to the organisation, that the business strategy needs to take into account. Hence, the SWOT analysis is where we summarise the key strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats in order to carry out an overall audit of the strategic position of a business nd its environment. A SWOT analysis is often represented as a two-by-two matrix as hown in Figure 3.3.

Figure 3.3 Format of a SWOT matrix

The language of a SWOT is important. It needs to be brief, with strengths and weaknesses related to critical success factors. Strengths and weaknesses should also be measured against the competition. All statements should be specific, realistic and supported by evidence. Some examples – not for the same organisation – could be:

- Strengths Strong product branding – market research shows a high awareness of our brands compared with the competition. We secure ‘best space’ in all branches of the top five retailers.

- Weakness We have poor cash flow. Against industry benchmarks we are in the bottom quartile. We exceed our overdraft limits on 19 days every quarter.

- Opportunity Demographic change in Europe and the US will provide a greater market for our products.

- Threat Low market growth will see increased concentration of business through acquisition. The poorest performing businesses will fail.

A key point that emerges from these examples is that strengths and weaknesses are found within the organisation (and hence discovered via the resource audit or the Boston Matrix) whereas opportunities and threats arise from outside the organisation (and hence can be found using PESTLE or the Five Forces model).

It is important to get right the balance between the external and the internal analysis. Completely changing the nature of the organisation because of the external analysis may lead to radical change but without any assurance that capability exists to deliver this successfully. Basing everything on an internal analysis may lead to little or no change, or changes that are internally focused and ignore the desires of the customers. Using both analyses is more balanced and is likely to contribute towards the creation of a more robust strategic direction.

EXECUTING STRATEGY

Executing new strategies implies risk because it involves change. There are three particular aspects of implementing strategy – the context for the strategy, the role of the leader and two tools that we can use – the Balanced Business Scorecard and the McKinsey 7-S Model.

There are five contextual issues to be considered.

- Time – how quickly does the new strategy need to be implemented? What pace of change is needed?

- Scope – how big is the change? Is the new strategic direction transformational or incremental?

- Capability – does the organisation have the required resources for the change? is the organisation adaptable and able to change? Are the experiences of change positive or negative?

- Readiness – is the whole organisation, or the part of it to be affected, ready to make the change?

- Strategic leadership – is there a strategic leader for the change?

In this context, the strategic leader will have the key role. Typically, the strategic leaders we read about are the top managers but strategic leadership does not have to be delivered from the top; there are many successful strategic changes that have been driven from other parts of the organisation. The leader needs to demonstrate the following key characteristics:

- Challenges the status quo all the time and sets new and demanding targets, never being prepared to tolerate unsatisfactory behaviour or performance.

- Establishes and communicates a clear vision of the direction to be taken, why it has to be taken and how the journey will be made. This means establishing the new mission, setting out objectives, identifying the strategies for achieving them and defining the specific tactics to deliver them. The leader also clearly communicates the values that underpin the business.

- ‘Models the way’ or ‘Walks the walk’. He or she demonstrates through their behaviour how everyone else should behave and act in order to deliver the strategy.

- Empowers people to deliver their part of the strategic change within the vision, values and mission that have been set out. The leader cannot be everywhere, so others need to play their part.

- Celebrates success with those who achieve it.

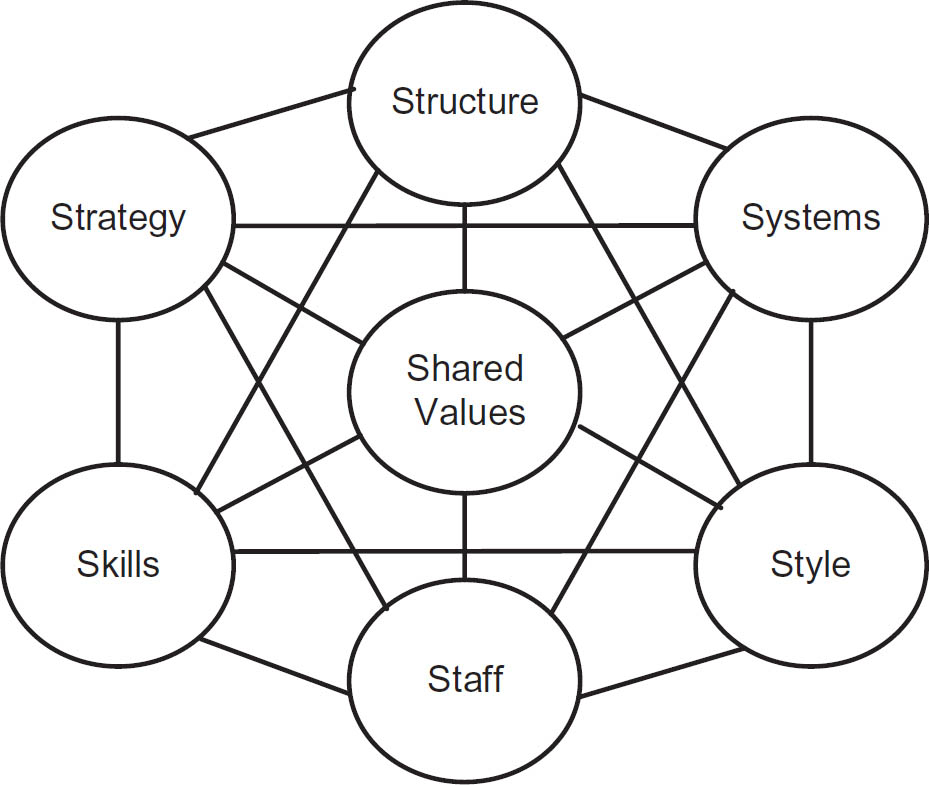

Two tools that help in the execution of strategy are the McKinsey 7-S Model shown in Figure 3.4 below and the Balanced Business Scorecard shown in Figure 3.5.

Figure 3.4 McKinsey’s 7-S Model

The 7-S model supposes that all organisations are made up of seven components. Three are often described as ‘hard’ components – strategy, structure and systems, and four as ‘soft’ – shared values, style, staff and skills.

These are the seven levers that can be used in the implementation of strategic change and they are all interlinked. All seven need attention if the strategy is to be executed successfully, because if there is a change with one, others will be affected. Changing one element, such as the strategy, means that all of the others have to change as well.

- The structure – the basis for building the organisation will change to reflect new needs for specialisation and coordination resulting from the new strategic direction.

- Formal and informal systems that supported the old system must change.

- The style or culture of the organisation will be affected by a new strategic direction. Values, beliefs and norms, which developed over time, may be revised or even swept away.

- The way staff are recruited, developed and rewarded may change. New strategies may mean relocating people or making them redundant.

- Skills – competences acquired in the past may be of less use now. The new strategy may call for new skills.

- Shared values are the guiding concepts of the organisation, the fundamental ideas that are the basis of the organisation. Moving from an ‘engineering first’ company to a ‘customer service first’ company would change the shared values.

As important as the individual elements of the 7-S model, are the connections between them. The execution of strategy will be flawed if, for example, there is a disconnect between the style adopted by management and the shared values of the organisation.

The Balanced Business Scorecard (BBS) can be thought of as the strategic balance sheet for an organisation as it captures the means of assessing the financial and non-financial components of a strategy. It therefore shows how the strategy execution is working and the effectiveness with which the levers for change are being used. The BBS supplements financial measures with three other perspectives of organisational performance – customers, learning and growth, and internal business processes. Vision and strategy connect with each of these as shown in Figure 3.5.

Figure 3.5 The Balanced Business Scorecard

The emphasis of the scorecard is to measure aspects of performance in a balanced way. In the past, managers have perhaps paid more attention to the financial measures but the BBS shows it is important to consider all of the four aspects. The customer perspective measures those critical success factors that provide a customer focus. It forces a detailed examination to be made of statements like ‘superior customer service’ so that everyone can agree what it means, and measures can be established to show the progress being made. It also identifies the need to consider how the customers view the organisation and its products or services. The delivery of value to the customers is likely to be affected by the internal processes so the process effectiveness also needs to be measured. The learning and growth perspective could generate a need for new products or new internal processes if the organisation is to continue to perform well. All of these aspects are important when evaluating organisational performance.

Each perspective answers questions like these:

- Financial – what level of income has been generated? How profitable is the business?

- Customer – how will we assess our customer satisfaction?

- Learning and Growth – how will we measure our ability to change and improve so that we constantly keep ahead of the competition?

- Internal Business Processes – how effective are the business processes that we must excel at to deliver customer value?

The BBS helps in the definition of two components which are vital to assess business performance; these are Critical Success Factors (CSFs) and Key Performance Indicators (KPIs).

The concept of CSFs was initially developed in the late 1970s when they were defined as ‘the few key areas where “things must go right” for the business to flourish and for a manager’s goals to be attained’ (Rockart in the Harvard Business Review, March/April 1979). The important words here are ‘few’, key’ and ‘must’. Not every activity is a key area; they are fewer in number than people think and success with them is critical but the CSFs mean that there are some goals that must be reached. However, it is of little use setting goals and then realising too late that you won’t make it. This is where KPIs are required. KPIs are the measures that show whether or not progress is being made towards the achievement of a CSF. KPIs measure specific areas of performance so also limit the amount of data that managers have to consider and act upon.

Let us see how this could work for a healthcare organisation, such as a hospital, using the BBS as a framework. First, the CSFs in the financial area will be considered. The hospital management might state that income must be greater than expenses, perhaps by a set percentage. It is important that the hospital sets this CSF specifically for its own circumstances rather than using a national target. CSFs must be our CSFs or there would be little identification with the effort required to achieve them. Generated from this CSF might therefore be strict cost control on the purchase of drugs and of treatment equipment. So, we would set financial KPIs to monitor and control the prescription of drugs and treatments; each KPI would have a set target which, in this case, could be a defined budget for expenditure of drugs and treatments each year. This is also an example of where CSFs in one area can affect CSFs in other areas; if the low cost drugs and treatments we use mean that it takes longer to get better with us, then how does that impact on a customer service CSF of reducing the waiting time for treatment?

It’s important that KPIs are defined such that they are SMART and that they are monitored regularly. If the drugs budget is exceeded within the first few months, what action will be taken to bring it back to budget before the overspend becomes too difficult to manage?

Other parts of the BBS can also generate CSFs so long as they are critical; for our hospital it is tempting to regard patient satisfaction as a critical success factor. Is it really critical or should the goal be to improve people’s health, provide life-saving surgery and so on? It can be difficult to determine the truly critical success factors. It is an excellent discipline to ensure that only those that are critical are identified; it is not possible to monitor too many factors at one time. There is a suggestion later in Chapter 6 about how CSFs and KPIs could be used in the construction of Business Activity Models.

SUMMARY

This chapter has looked at the reasons why organisations develop strategies and how they might do this. We have explored the complexity of this process and offered ideas about how strategies are developed taking account of entrepreneurial approaches and formal planning. The chapter has also described the external factors influencing strategy – the outside/in approach – and an internal analysis approach – the inside/out approach. Finally we looked at the execution of strategy and IS strategy considerations such as performance measurement using the BBS, CSFs and KPIs.

REFERENCES

Johnson, G., Scholes, K. and Whittington, R. (2008) Exploring Corporate Strategy, 8th edn. FT Prentice Hall, Harlow.

Porter, M. E. (1980) Competitive Strategy: Techniques for Analysing Industries and Competition. Free Press, New York, NY.

FURTHER READING

Kaplan, R. S. and Norton, D. P. (1996) ‘Using the balance scorecard as a strategic management system’, The Harvard Business Review Jan/Feb.

Porter, M. E. (1998) Competitive Advantage: Creating and Sustaining Superior Performance. Free Press, New York, NY.

Quinn, J. and Mintzberg, H. (1995) The Strategy Process. Prentice Hall, Upper Saddle River NJ.

Thompson, J. and Martin, F. (2010) Strategic Management: Awareness and Change, 6th edn. CENGAGE Learning, Boston, MA.