INTRODUCTION

A business case is a key document in a business analysis project and is the place where the analysts present their findings and propose a course of action for senior management to consider. This chapter considers the purpose, structure and content of a business case and provides some guidance on how to assemble the information and to present the finished product. One thing worth remembering is that, to some extent, a business case is a ‘sales’ document, aimed at getting people to take a decision. Therefore, some of the key rules of successful selling apply: stress benefits, not features; sell the benefits before discussing the cost; get the ‘buyers’ to understand the size of the problem – or opportunity – before presenting the amount of time, effort and money that will be needed to implement a solution.

THE BUSINESS CASE IN THE PROJECT LIFECYCLE

A question often asked about the business case is ‘when should it be produced?’ This issue is addressed in Figure 9.1. As the illustration shows, a business case is a living document and should be revised as the project proceeds and as more is discovered about the proposed solution and the costs and benefits of introducing it. In addition, organisations and the environments in which they operate are not static and so the business case must be kept under review to ensure that changing circumstances have not invalidated it. The initial business case often results from a feasibility study, where the broad requirements and options have been considered and where ‘ballpark’ estimates of costs and benefits are developed. The ballpark figures must, however, be revisited once more detailed analysis work has been completed and a fuller picture has emerged of the options available. It should also be examined again once the solution has been designed and much more reliable figures are available for the costs of development. The business case should next be reviewed before the solution is deployed, precisely because the costs of deployment are now more reliable. Also, business circumstances may have changed and it may not be worth proceeding to implementation. Finally, once the proposed solution has been in operation for a while, there should be a benefits review to determine the degree to which the predicted business benefits have been realised and to identify actions to support the delivery of these benefits.

Figure 9.1 The business case in the project lifecycle (Reproduced by permission of Assist Knowledge Development Ltd)

Figure 9.1 refers to each of these review points as ‘decision gates’. The concept shown, now widely used in project management, is that projects should pass certain tests – not least those relating to their business viability – before they can be allowed to proceed to the next stage.

IDENTIFYING OPTIONS

The first step in putting together a business case is to identify and explore the various options that exist for solving the business issue. There are actually two kinds of options:

- Business options that explore what the proposed solution is intended to achieve in business terms – for example, ‘speed up invoice handling by 50 per cent’ or ‘reduce the number of people we need to staff our supermarket’.

- Technical options that consider how the solution is to be implemented, often through the use of information technology.

At one time, it was considered that these two elements should be considered separately and deal with business first, the aim being to avoid the technical ‘tail’ wagging the business ‘dog’. Nowadays, however, most changes to business practice involve the use of IT in some form and it is often the availability of technology that makes the business solutions possible. For example, one way of reducing the need for staff in a supermarket would be to enable customers to scan their purchases themselves using ‘smart’ bar codes. For this reason, it is a bit difficult to keep business and technical options separate but it remains true that business needs should drive the options process, rather than the use of technology for its own sake.

The basic process for developing options is shown in Figure 9.2. Identifying options is probably best achieved through some form of workshop, where brainstorming and other creative problem-solving approaches can be employed. Modelling techniques such as Business Activity Modelling (Chapter 6) or Business Process Modelling (Chapter 7) are also useful to help generate options. The aim is to get all of the possible ideas out on the table before going on to consider which ones are most promising. Even if some of the ideas seem a bit far-fetched, they may provide part of the actual solution or stimulate other people to come up with similar, but more workable, suggestions. Another way of identifying options is to study what other organisations – possibly your competitors – have done to address the same issues.

Figure 9.2 Process for developing options (Reproduced by permission of Assist Knowledge Development Ltd)

Once all the possibilities have been flushed out, they can be subjected to evaluation to see which ones are worth examining further. Some ideas can usually be rejected quite quickly as being too expensive, or taking too long to implement, or being counter-cultural. The criteria for assessing feasibility are examined in more detail in the next part of this chapter.

Ideally, the shortlist of options should be reduced to three or four, one of which will usually be that of maintaining the status quo, the ‘do nothing’ option. The reason for restricting the list to three or four possibilities is that it is seldom practical, for reasons of time or cost, to examine more than this in enough detail to be taken forward to the business case. Each of the short-listed options should address the major business issues but offer some distinctive balance of the time they will take to implement, the budget required and the range of features offered. Sometimes, though, the options are ‘variations on a theme’, with one just dealing with the most pressing business issues and others offering various additional features. This situation is illustrated in Figure 9.3.

Figure 9.3 Incremental options (Reproduced by permission of Assist Knowledge Development Ltd)

In Figure 9.3, the bottom option just deals with the most pressing issues, as quickly as possible and at minimal cost. The next option adds some additional features to the solution but costs more and takes longer. The last option a comprehensive solution but obviously takes the longest and costs the most.

One option that should always be considered – and which should usually find its way into the actual business case – is that of doing nothing. Sometimes, it really is a viable option and might even be the best choice for the organisation. Often, though, there is no sensible ‘do nothing’ option as some form of business disaster may result from inaction. In this case, the decision-makers may not be aware that action is imperative and so spelling out the risks and consequences of doing nothing becomes an important part of making the case for the other options.

ASSESSING PROJECT FEASIBILITY

There are many issues to think about in assessing feasibility but all fall under the three broad headings illustrated in Figure 9.4.

Figure 9.4 Aspects of feasibility (Reproduced by permission of Assist Knowledge Development Ltd)

Business feasibility issues include whether the proposal matches the business objectives and strategy of the organisation and – if it is a commercial firm – if it can be achieved in the current market conditions. There is the question of whether the proposed solution will be delivered in sufficient time to secure the desired business benefits. The proposal must ‘fit’ with the management structure of the organisation and with its culture, as lack of cultural fit is often a cause of projects not meeting the expectations held for them. The solution must align with the enterprise architecture for the organisation. The proposal may be for major process change so may have to align with other processes, including those that are not changing, so alignment with the processes defined in the business architecture must also be considered. Whatever is proposed must be within the competencies of the organisation and its personnel, or there must be a plan for the development of these competencies. Finally, many sectors are now heavily regulated and the proposed solution must be one that will be acceptable to the regulators and not infringe other law or treaty obligations.

In assessing technical feasibility, one is normally – though not necessarily – considering IT. The proposed solution must meet the organisation’s demands in terms of system performance, availability, reliability, maintainability and security. It must be asked if the solution is scalable, up or down, if the circumstances of the organisation change. The organisation must possess the technical skills to implement the solution, or supplement these with help from outside. Few IT systems are now completely detached from other systems and so the issue of compatibility must be considered. If the solution involves an off-the-shelf software package, thought should be given to the amount of customisation that would be required and whether this would cause technical difficulties. Finally, consideration is needed regarding whether the proposed solution is a proven one or places excessive reliance on leading edge – that is to say, unproven – technologies. Many organisations would prefer a less ambitious but reliable solution to a more advanced one that comes with a lot of technological risk.

Financial feasibility is about whether the organisation can afford the proposed solution. There may already be a budget imposed. The organisation needs either to have the required funds available or to be in a position to borrow them. Every organisation will have some rules or guidelines about what constitutes an acceptable return on its investment and methods of calculating this are considered later in this chapter. Even if a project pays for itself in the end, it may have unacceptable high costs on the way and so cash flow must also be considered. Finally, all organisations specify some time period over which payback must occur and, in the case of IT projects, the payback periods are often very short, sometimes within the same accounting year as the investment.

Another tool that can be used in assessing feasibility is a PESTLE analysis. PESTLE examines the environment outside an organisation, or perhaps within an organisation but outside the area being studied. It can be used to assess feasibility like this:

- Political: Is the proposed solution politically acceptable?

- Economic: Can the organisation afford the solution?

- Socio-cultural: Does the solution fit with the organisation’s culture?

- Technological: Can the solution be achieved, technically?

- Legal: Is it legal, will the regulator allow it?

- Environmental: Does it raise any ‘green’ environmental issues?

A final tool that can be employed to assess the feasibility of an option is a ‘force-field analysis’, illustrated in Figure 9.5.

Figure 9.5 Force-field analysis

With a force-field analysis, we consider those forces inside and outside the organisation that will support adoption of the proposal and those that will oppose it; and we need to be sure that the positive forces outweigh the negative. The forces may include the PESTLE factors mentioned above, the elements identified in Figure 9.4 and also the key stakeholders in the organisation (see Chapter 6). If we conclude that the negative forces are just too strong, then the proposal is not feasible and must be abandoned or re-cast in a way that gets more positive forces behind it.

In considering the feasibility of options, we also need to think about their impacts and risks. Because these form part of the business case itself, we discuss them later in this chapter.

STRUCTURE OF A BUSINESS CASE

Organisations differ in how they like to have business cases presented. Some like large, weighty documents with full analyses of the proposals and all the supporting data. Others like a short, sharp presentation of the main points – we have come across one organisation that mandates that business cases be distilled into a single page of A4. If this sounds cavalier, remember that the people who have to make the decisions on business cases are busy senior managers, whose time is at a premium. Whatever their size, however, the structure and content of most business cases are similar and tend to include these elements:

- introduction;

- management summary;

- description of the current situation;

- options considered;

- analysis of costs and benefits;

- impact assessment;

- risk assessment;

- recommendations;

- appendices, with supporting information.

We shall examine each of these elements in turn.

Introduction

This sets the scene and explains why the business case is being presented. Where relevant, it should also describe the methods used to examine the business issue and acknowledge those who have contributed to the study.

Management summary

In many ways, this is the most important part of the document as it is possibly the only part that the senior decision-makers will study properly. It should be written after the rest of the document has been completed and should distill the whole of the business case into a few paragraphs. In an ideal situation, three paragraphs should suffice:

- What the study was about and what was found out about the issues under consideration.

- A survey of the options considered, with their principal advantages and disadvantages.

- A clear statement of the recommendation being made and the decision required.

If you cannot get away with only three paragraphs, try at least to restrict the management summary to one or two pages.

Description of the current situation

This section of the document discusses the current situation and explains where the problems and opportunities lie. As long as these issues are covered to a sufficient level of detail, it is good to keep this section as short as possible; senior managers often complain of having to read pages and pages to find out what they knew already! Sometimes, though, the real problems or opportunities uncovered are not what management thought they were when they instituted the study. In that case, more space will have to be devoted to clarifying the issues and exploring the implications for the business.

Options considered

In this section of the document, the options to be considered are described with a brief explanation of why we are rejecting those not recommended. More coverage should be devoted to describing the recommended solution and why we are recommending it. As represented in Figure 9.3, there may well be a series of incremental options, from the most basic one to one that addresses all of the issues raised.

Analysis of costs and benefits

Cost–benefit analysis is one of the most interesting – and also the most difficult – aspects of business case development. Before examining the subject in detail, it is worth mentioning that it is good psychology to present the benefits before the costs. Doing this will increase the expectations of the likely costs and will help the decision-makers to appreciate the benefits before they are told the costs of achieving them. In other words, what we are presenting is actually a benefit–cost analysis even though by convention it is always referred to as a cost–benefit analysis.

Although cost–benefit analysis is interesting, it does pose a number of challenges:

- working out in the first place where costs will be incurred and where benefits can be expected;

- being realistic about whether the benefits will be realised in practice;

- placing a value on intangible elements like ‘improved customer satisfaction’ or ‘better staff morale’.

The last point concerns the types of costs and benefits that need to be considered. Costs and benefits are either incurred, or enjoyed, immediately or in the longer term. They are also either tangible, which means that a credible – usually monetary – value can be placed on them, or intangible, where this is not the case. Combining these elements, we find that costs and benefits fit into one of four categories, as illustrated in Figure 9.6.

Figure 9.6 Categories of costs and benefits (Reproduced by permission of Assist Knowledge Development Ltd)

Costs tend to be mainly tangible, whereas benefits are often a mixture of the tangible and intangible. In some organisations, the managers will not consider intangible benefits at all and this often makes it difficult – or even impossible – to make an effective business case. How, for instance, does one place a value on something like a more modern company image achieved through adopting a new logo? In theory, it should be possible to put a numeric value on any cost or benefit; the practical problem is that we seldom have the time, or the specialist expertise – for example, from the field of operational research – to do so.

If intangible benefits are allowed, though, it is very important not to over-state them or, worse, to put some spurious value against them. The danger here is that the decision-makers simply do not believe this value and this then undermines their confidence in other, more soundly based, values. With intangible benefits, it is a much better policy to state what they are and even to emphasise them but to leave the decision-makers to put their own valuations on them.

Another pitfall in cost–benefit analysis is to base them on assumptions. For example, we might say something like ‘If we could achieve a 20% reduction in the time taken to produce invoices, this would amount to 5,000 hours per year or a cost saving of £25,000.’ This will only prove acceptable to the decision-makers if the assumption is plausible. If you can, use assumptions that are common within the organisation and always err on the side of conservatism, which is to under-claim rather than over-claim.

Looking at the four categories of costs and benefits already described, there are some areas where costs and benefits typically arise and there are standard ways of quantifying them.

Tangible costs

- Development staff costs: In many projects, particularly those that involve developing new processes or IT systems, these will be a major cost element. To work them out, we need a daily rate for the staff concerned – probably available from HR or Finance – and an outline project plan showing when and how many of the resources will be required. If you are using external consultants, then the costs here will be subject to negotiation and contract.

- User staff costs: These are often forgotten but can be significant. User staff will have to be available for the initial investigation and analysis, possibly during the development of new systems, to conduct user acceptance testing and to be trained in the new systems and work practices. Again, daily rates can be used in combination with an outline plan of the amount of user involvement.

- Equipment: Where IT is involved, there will often be a need to purchase new hardware. For this, estimates or quotations can be obtained from potential suppliers. Other equipment may also be required such as desks, tables.

- Infrastructure: This includes elements like cabling and networks and, again, estimates will be required from suppliers.

- Packaged software: Estimates of the cost of this can be obtained from package vendors, probably based on the proposed number of users or licenses. Where tailoring of a package is envisaged, estimates of the effort and cost involved can be requested also.

- Relocation: This can be quite difficult to cost. The costs could include those of the new premises, either rented or bought, refurbishment and the actual moving costs. There may also be costs associated with surrendering existing leases and so on.

- Staff training and retraining: To work this out, we need to know how many people need to be trained and what they need to learn. Ideally, this requires training needs analysis which examines the skills gaps and identifies the best way of developing the additional skills. If an assessment of the effort required to develop training material is needed, a rough estimate may be developed by multiplying the delivery time for a course by a factor of 10. For example, a 2-day training event will typically require 20 days development effort.

- Ongoing costs: Once any new systems are in place, they will require maintenance and support, and quotations for this can be obtained from the vendors. If this is not possible, a very rough rule of thumb is to allow support costs of 15 per cent of operational costs in the first year after installation and then 10 per cent thereafter. But this is very crude and actual quotations are much to be preferred if they can be obtained.

Intangible costs

- Disruption and loss of productivity: However good a new process or system is in the long run, there is bound to be some disruption as it is introduced. The level of disruption is very difficult to predict when implementing any business change. Also, if parallel running of old and new IT systems is used to smooth the transition, there will be a tangible cost involved as well.

- Recruitment: This ought to be tangible but organisations often have little idea of the total cost to recruit someone although elements of this cost, such as agency fees, will be tangible. But if new staff or skills are needed, there will be costs involved in getting the new staff and inducting them into the organisation.

Tangible benefits

- Staff savings: This is the most obvious saving, though many organisations are now so lean that it is hard to see where further reductions will come from. In calculating the savings, we need the total cost of employing the people concerned – including things like national insurance, pensions and other benefits and sometimes the space they occupy. The HR or accounts departments should be able to supply this information. Do not forget, though, that if people are to be made redundant, there will be one-off redundancy costs that must be set against the ongoing saved staff costs.

- Reduced effort and improved speed of working: If staff posts are not completely removed, it may be possible to carry out some tasks in a shorter timescale thus freeing up time for other work. This is a tangible benefit if the effort to carry out the task is measured and compared with the expected situation after the change.

- Faster responses to customers: Again, it would be necessary to make a pre-change measurement of the time taken to respond to customers’ needs in order to quantify any possible benefits.

- Reduced accommodation costs: These may have already been factored into the cost of employing staff (see ‘Staff savings’ above) but new hardware may also save space and, perhaps, people may be able to work from home some or all of the time. The facilities or finance department should have some idea about the cost of accommodation.

- Reduced inventory: New systems – especially ‘just in time’ systems – usually result in the need to hold less stock. Finance and logistics experts should be able to help in quantifying this benefit.

- Other costs reductions: These include things like reduced overtime working, the ability to avoid basing staffing levels on workload peaks, reductions in time and costs spent on travel between sites and in the use of consumables.

Intangible benefits

- Increased job satisfaction: This may result in tangible benefits like reduced staff turnover or absenteeism but the problem is that we cannot prove in advance that these things will happen.

- Improved customer satisfaction: This, too, is intangible unless we have sound measures to show, for example, why customers complain about our products or services.

- Better management information: It is important to distinguish between better management information and an increased amount of management information. Better information should lead to better decisions but it is difficult to value.

- Greater organisational flexibility: This means that the organisation can respond more quickly to changes in the external environment, through having more flexible systems and staff who can be switched to different work relatively quickly.

- More problem-solving time: Managers freed from much day-to-day work should have more time to study strategic and tactical issues.

- Improved presentation or better market image: New systems often enable an organisation to present itself better to the outside world.

- Better communications: Many people report that poor communications within their organisation are a problem so improving communications would clearly be beneficial. However, again, it would be difficult to place a value on this.

Avoided costs

One particular form of benefit, which is worth thinking about, is what we might call ‘avoided costs’. For example, in the run-up to the year 2000, many organisations were faced with the costs of making their computer systems millennium-compliant. IT departments often instead suggested the wholesale replacement of systems, thereby avoiding the costs of adapting the old systems. In such a case, an investment of, say, £2 million in a new system might be contrasted with an avoided cost of £1 million just to make the old legacy systems compliant. There are often situations where an organisation has to do something and has already budgeted for it; that budget can be offset against a more radical solution that would offer additional business benefits.

Presenting the financial costs and benefits

Once the various tangible costs and benefits have been assessed, they need to be presented so that management can see whether and when the project pays for itself. As this is a somewhat complex topic, it is examined separately in the section ‘Investment appraisal’.

Impact assessment

In addition to the costs and benefits already mentioned, for each of the options we need to explore in the business case any impacts that there might be on the organisation. Some of these impacts may have costs attached to them but some may not and are simply the things that may happen as a result of adopting the proposed course of action. Examples include:

- Organisation structure: It may be necessary to reorganise departments or functions to exploit the new circumstances properly. For example, to create a single point of contact for customers or more generalist rather than specialist staff roles. This will naturally be unsettling for the staff and managers involved and a plan must be made to handle this.

- Interdepartmental relations: Similarly, the relationships between departments may change and there may be a need to introduce service level agreements or in other ways redefine these relationships.

- Working practices: New processes and systems invariably lead to changes in working practices and these must be introduced carefully and sensitively.

- Management style: Sometimes, the style that managers adopt has to change. For example, if we de-layer the organisation and give front-line staff more authority to deal with customers, their managers’ role changes as well.

- Recruitment policy: The organisation may have to recruit different types of people and look for different skills.

- Appraisal and promotion criteria: It may be necessary to change people’s targets and incentives in order to encourage them to display different behaviours, for example to be more customer-focused.

- Supplier relations: These may have to be redefined. For example, outsourcing IT services would work much better with a co-operative customer/supplier relationship than with the adversarial situation that too often seems to exist.

Whatever the impacts are, the business case needs to spell them out. It must also make clear to the decision-makers what changes will have to be made in order to fully exploit the opportunities available, and the costs these changes are likely to incur.

Risk assessment

No change comes without risk and it is unrealistic to think otherwise. A business case is immeasurably strengthened if it can be shown that the potential risks have been identified and that suitable countermeasures are available. A comprehensive risk log (sometimes called the risk register) is probably not required at this stage – that should be created when the change or development project proper starts – but the principal risks should be identified. For each risk, the following should be recorded:

- Description: The cause of the risk should be described and also its impact, for example ‘uncertainty over the future leads to the resignation of key staff, leaving the organisation with a lack of experienced personnel’.

- Impact assessment: This should attempt to assess the scale of the damage that would be suffered if the risk occurred. If quantitative measures can be made, so much the better, otherwise a scale of ‘small, ‘moderate’ or ‘large’ will suffice.

- Probability: How likely is it that this risk will materialise? Again, precise probabilities can be calculated but it is probably better to use a scale of ‘low’, ‘medium’ or ‘high’.

- Countermeasures: This is the really important part, the question being what can we do to either reduce the likelihood of the risk occurring or lessen its impact if it does. We may also try to transfer the risk’s impact onto someone else, for example through the use of insurance.

- Ownership: For each risk, we need to decide who would be best placed to take the necessary countermeasures. This may involve asking senior managers within the organisation to take the responsibility.

If there seem too many risks associated with the proposal, it is a good idea to document only the major ones – the potential ‘show-stoppers’ – in the body of the business case and to put the rest in an appendix.

Recommendations

Finally, we need to summarise the business case and make clear the decisions that the senior managers are being asked to take. If the business case is for carrying out a project of some sort, then an outline of the main tasks and timescales envisaged is useful to the decision-makers. This is best expressed graphically, as a Gantt/bar chart as illustrated in Figure 9.7.

Figure 9.7 Gantt/bar chart for a proposed project

Appendices and supporting information

Where detailed information needs to be included in the business case, this is best put into appendices. This separates out the main points, that are put in the main body of the case, from the supporting detail. If supporting statistics have to be provided, they too should go into appendices, perhaps with a summary graph or chart in the main body. The detailed cost–benefit calculations may also be put into appendices.

INVESTMENT APPRAISAL

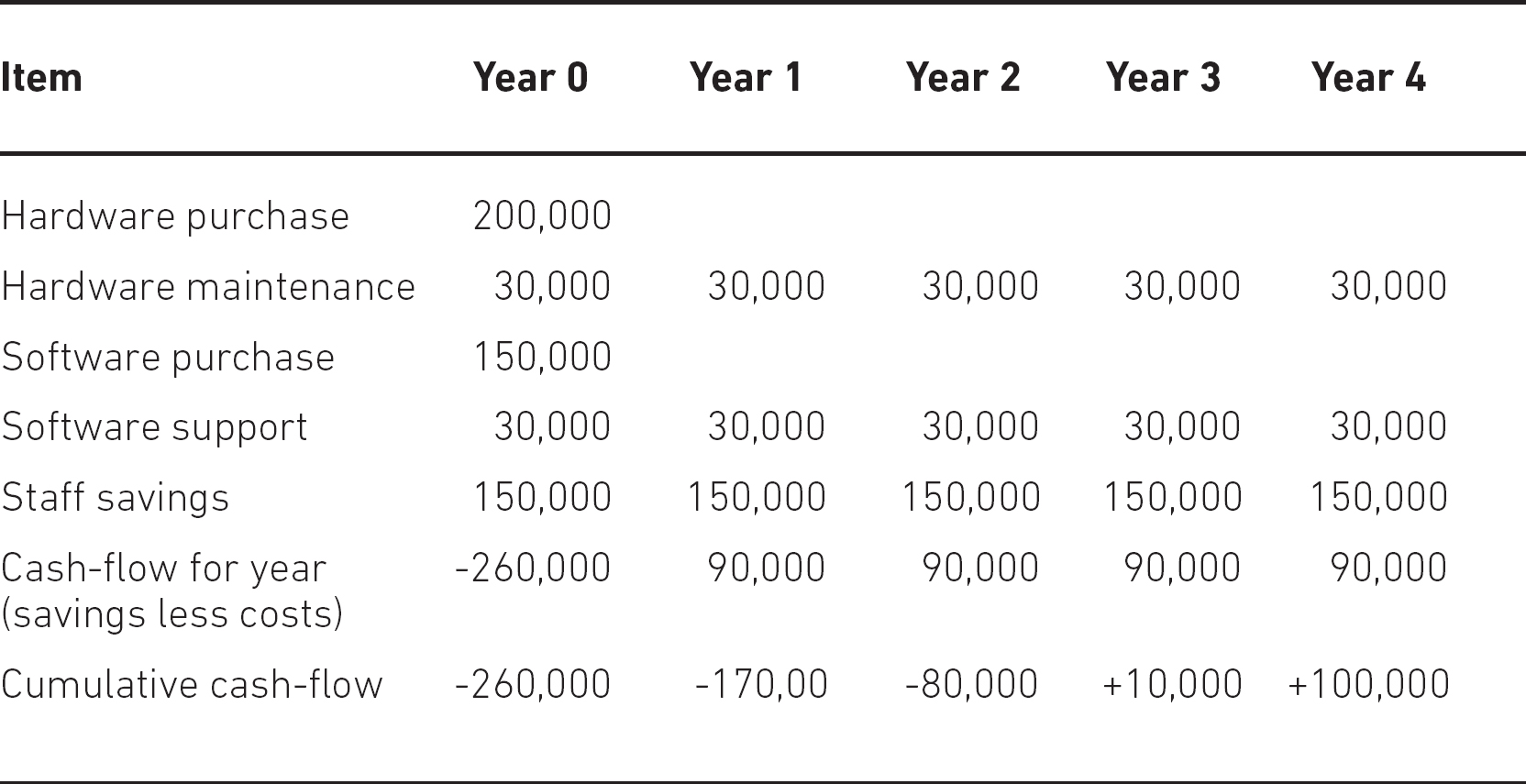

In this part of the business case, the financial aspects – in other words the tangible costs and benefits – are contrasted so see if, and when, the project will pay for itself. The simplest way of doing this is by using what is called a ‘payback’ calculation, which is in effect a cash-flow forecast for the project. An example of a payback calculation is given in Table 9.1. It shows immediate costs of £200,000 for hardware and £150,000 for software for a new system, and ongoing costs of £30,000 for hardware maintenance and £30,000 for software support and upgrades. The tangible benefit will be the removal of some clerical posts, valued at £150,000 per year. Note that, in these calculations, the convention is to refer to the year in which the investment is made as ‘Year 0’.

Table 9.1 Example of a payback calculation

In Year 0, the costs considerably outweigh the benefits, because of the large capital expenditures but thereafter benefits exceed costs by some £90,000 per year. By working out the cumulative positions, we discover that the accumulated benefits finally exceed the accumulated costs in Year 3 and thereafter build up at £90,000 per year.

Payback calculations have the virtue of being easy to understand and relatively easy to construct, although getting reliable figures can sometimes be a headache. Where interest rates and inflation are low they provide a reasonable forecast of what will happen. However, they do not take account of what accountants call the ‘time value of money’. This is the simple fact – which we all understand from our personal experience – that money spent or saved today is not worth the same as it will be next year or in five years’ time. In part this is the effect of inflation but, even with low or zero inflation, there are other things that we could do with the money besides investing in this project. We might, for instance, leave it in the bank to earn interest. Or, conversely, we might have to borrow money and pay interest to finance the project.

A method that takes account of the time value of money is known as discounted cash flow (DCF) which leads to a ‘net present value’ (NPV) for the project. This means that all of the cash-flows in years after Year 0 are adjusted to today’s value of money. Management accountants work out the ‘discount rate’ to use in a discounted cash flow calculation by studying a number of factors including the likely movement of money-market interest rates in the next few years. The mechanism for doing this is outside the scope of this book but interested readers are referred to the ‘Further reading’ section at the end of this chapter. Let us suppose, though, that the management accountants decide we should be using a discount rate of 10 per cent. We can then find the amounts by which we should discount the cash-flows in Years 1 to 4 either by using the appropriate formula in a spreadsheet or looking up the factors in an accounting text-book. For a 10 per cent discount rate, the relevant factors are shown in Table 9.2.

Table 9.2 Example of a net present value calculation

Table 9.2 represents the same project that was analysed in Table 9.1. With the cash flows from Years 1 to 4 adjusted to today’s values by multiplying by the discount factor, we can see that the project is not such an attractive investment as the payback calculation suggested. It does pay for itself, but now only in Year 4 and not by as great a margin as before.

We can perform a sensitivity analysis on these results to see how much they would be affected by changes in interest rates. If we had used a discount rate of 5 per cent, for example, we would have got an NPV of £59,140 and a 15 per cent rate would have produced an NPV of –£2960.

One final measure that some organisations like to use is what is called the ‘internal rate of return’ (IRR). This is a calculation that assesses what sort of return on investment is represented by the project in terms of a single percentage figure. This can then be used to compare projects one with another to see which are the better investment opportunities, and to compare them all with what the same money could earn if just left in the bank. So, for example, if the IRR of a project is calculated at three per cent and current bank interest rates are five per cent, then on financial grounds alone it would be better not to spend the money.

IRR is worked out by standing the DCF/NPV calculations on their head. The question we are asking is, what discount rate would we have to use to get a net present value of zero after five years (or whatever period the organisation mandates should be used for the calculation)? In other words, at what point would financial costs and benefits precisely balance each other? One way of calculating the IRR is by trial and error. For example, setting up a spreadsheet and trying different discount rates until an NPV of zero is produced – Microsoft Office Excel has an automated function to do this. In the case of our example project, the IRR is around 14.42 per cent. If this were being compared with another project offering only five per cent, then our project would be the more attractive one. However, IRR does not take account of the overall size of the project, so that the project with the smaller IRR may produce more actual pounds, or euros or dollars in the end. For this reason, most accounting textbooks agree that DCF/NPV is the best method of assessing the value of an investment, whilst acknowledging that many managers like the simplicity of the single-figure IRR.

PRESENTATION OF A BUSINESS CASE

There are two basic ways in which a business case can be presented and often there is a need for both: as a written document and as a face-to-face presentation. In both cases, the way the business case is presented can often have a major impact on whether it is accepted or not and there are some simple rules that apply to both approaches:

- Think about the audience: Readers of reports and attendees at presentations have a variety of interests and attitudes. Some like to have all of the details, others prefer an overview. As far as possible, try to address the concerns of each of the decision-makers in the report or presentation. (See the information in Chapter 6 on stakeholder management, for more on this.)

- Keep it short: You may have to use a pre-set format or template for your report, in which case the actual sections may force you into a long document. However, try as far as possible to keep the business case concise.

- Consider the structure: We have provided here a good basic structure for a written business case. For a presentation, the old rule still holds good:

- tell ’em what you’re going to tell ’em;

- tell ’em;

- tell ’em what you’ve told ’em.

You need to build to a logical conclusion that starts with the current situation and leads to the decision you need made.

- Think about appearances: Again, you may be constrained by a template here but, if not, remember you have to induce the decision-makers to read your business case! Use lots of white space, pictures and diagrams instead of tables, and use colour as well. For a presentation, avoid dozens of bullet-point slides, which tend to simply repeat what is in the report anyway; instead use pictures, diagrams and colour to provide a more visual representation for the decision-makers.

RAID AND CARDI LOGS

We have seen that the business case documents the risks of a proposed project and it also may set out any constraints, assumptions or dependencies on which it has been based. Since all of these will have ongoing effects throughout the project, this is a good point at which to set up logs that will assist us in managing these factors. A RAID log documents risks, assumptions, issues and dependencies; a CARDI log includes these elements plus constraints.

A CARDI log therefore contains sections that document:

- Constraints: The main constraints on any project are those of the ‘iron triangle’ – time, cost (or resources) and product/quality. But other constraints may need to be taken into account as well, such as the need to comply with certain legislation, to use certain standards or to make sure an IT solution runs on a specific platform.

- Assumptions: The business case, and thus the project, may rest on certain assumptions, for example that government funding may be available for part of the project. These assumptions should be documented and actions identified to test whether they are valid.

- Risks: The risks documented in the business case form the start of the overall risk log for the project and will be added to as more is known about it. The log should document the risks themselves, their probability of occurrence and scale of impact, the actions proposed to avoid or mitigate them and who should own each risk. As well as new risks arising during the project, others will change and still more can be retired if they do not, in fact, occur.

- Dependencies: Because modern organisations are so complex, an individual project often has dependencies on other projects, or may be depended upon by other projects. For instance, a project to introduce a new IT system may depend on a project to recruit people to operate it and vice versa. Capturing details of these dependencies makes sure that they are kept in mind at all times.

- Issues: An issue is something that has occurred on a project which could have an effect on it (for good or ill) and which therefore needs to be managed. Some issues are risks which have materialised. For example, if it is known at the outset that the project team is inexperienced, this is an issue rather than a risk because it has 100 per cent probability of occurring. As with risks, the issues part of the CARDI log documents what each issue is, what should be done about it and whose responsibility this is.

Since a CARDI/RAID log is established at the time the initial business case is created, its entries will probably be at a high-level at this stage and then gain detail as the project proceeds and more is known about its complexities.

SUMMARY

A coherent and well-researched business case should be an important guiding document for any change project. Developing a business case starts by identifying the possible options and then assessing their feasibility. The business case itself follows a fairly clearly defined format, leading to clear recommendations to the decision-makers. There are several approaches to investment appraisal, which assesses the financial costs and benefits of a proposed change project. A CARDI/RAID log can be used to document important information about factors that could affect the success of the project. At a designated point after the project has been completed, the business case should form the basis for a review to determine whether the expected benefits have been realised in practice and to identify any actions required to support the delivery of those benefits; this is discussed in Chapter 14.

FURTHER READING

Blackstaff, M. (2012) Finance for IT Decision Makers: A practical handbook, 3rd edn. BCS, Swindon.

Boardman, A. E., Greenberg, D. H., Vining, A. R. and Weimer, D. L. (2013) Cost–Benefit Analysis: Concepts and Practice, 2nd edn. Prentice Hall, Upper Saddle River, NJ.

Gambles, I. (2009) Making the Business Case: Proposals that Succeed for Projects that Work. Gower Publishing, Farnham.

Harvard Business Review on the Business Value of IT, (1999) Harvard Business School Press.

Schmidt, M. J. (2002) The Business Case Guide, 2nd edn, Solution Matrix (available from www.solutionmatrix.com).

Ward, J. and Daniel, E. (2012) Benefits Management: Delivering Value from IS and IT Investments. Wiley, Chichester.