CHAPTER SEVEN

Craft the Decision Objectives and Value Measures

Management by objective works—if you know the objectives. Ninety percent of the time you don’t.

—Peter Drucker

Our age is characterized by the perfection of means and the confusion of goals.

—A. Einstein

7.1 Introduction

In the previous chapter, we discuss the critical role of the decision analyst in framing the decision. With this understanding of the decision frame, which may include a partial list of objectives, we next strive to identify the full list of objectives that the decision maker(s) seek to achieve with the decision. Of course, the identification of a significant new objective can change our frame. In addition to improving the decision frame, decision analysts use the objectives as the foundation for developing the value measure(s) used to evaluate the alternatives and select the best alternative(s).

We believe that it is good practice in any decision analysis to consider values and objectives before determining the full set of alternatives. Our experience is that decision analysis studies that develop alternatives first and use value measures only to distinguish those alternatives often miss several important objectives and therefore miss the opportunity to create a broader and more comprehensive set of alternatives that have the potential to create more value.

As the opening quote from Peter Drucker notes, although objectives are essential for good management decision making, they may be difficult to identify. In order to develop a complete list of decision objectives for an important decision, the decision analyst should interact with a broad and diverse group of decision makers, stakeholders, and subject matter experts.

To identify objectives, it is generally not sufficient to interact with only the decision maker(s) because, for complex decisions, they may not have a complete and well-articulated list of objectives. Instead, significant effort may be required to identify, define, and, perhaps, even carefully craft, the objectives based on many interactions with multiple decision makers, diverse stakeholders, and recognized subject matter experts. The ability to craft a comprehensive, composite set of objectives that refines the decision frame requires several of the soft skills of decision analysis (see Chapter 4).

The chapter is organized as follows. In Section 7.2, we describe shareholder and stakeholder value, which is the basis for the decision objectives. In Section 7.3, we describe why the identification of objectives is challenging. In Section 7.4, we list some of the key questions we can use to identify decision objectives and the four major techniques for identifying decision objectives: research, interviews, focus groups, and surveys. In Section 7.5, we discuss key considerations for the financial objective of private companies and cost objectives of public organizations. In Section 7.6, we discuss key principles for developing value measures to measure a priori how well an alternative could achieve an objective. In Section 7.7, we describe the structuring of multiple objectives, including objective and functional value hierarchies; describe four techniques for structuring objectives: Platinum, Gold, Silver, and Combined Standards; identify some best practices; and describe some cautions about risk and cost objectives. In Section 7.8, we describe the diverse approaches used to craft the objectives for the three illustrative problems. We conclude with a summary of the chapter in Section 7.9.

7.2 Shareholder and Stakeholder Value

Decision objectives should be based on shareholder and stakeholder value. Value can be created at multiple levels within an enterprise or organization. An organization creates value for shareholders and stakeholders by performing its mission (which usually helps to define the potential customers); providing products and services to customers; improving the effectiveness of its products and services to provide better value for customers; and improving the efficiency of its operations to reduce the resources required to provide the value to customers. Defining value is challenging for both private and public organizations. Private companies must balance shareholder value with being good corporate citizens (sometimes called stakeholder value). The management literature includes discussion of stakeholder value versus shareholder value for private companies (Charreaux & Desbrieres, 2001). Public organizations, which operate without profit incentives, focus on stakeholder value with management and employees being key stakeholders.

Next, we consider the shareholder and stakeholder objectives in a private company example and the stakeholder objectives in a public organization.

7.2.1 PRIVATE COMPANY EXAMPLE

Consider a large publicly owned communications company operating a cellular network that provides voice and data services for customers. The stakeholders include the shareholders, the board of directors, the leadership team, the employees (managers, designers, developers, operators, maintainers, and business process personnel), the customers, the cell phone manufacturers, the companies that sell the cell phone services, and the communities in which the company operates. The competition includes other cellular communications companies and companies that provide similar products and services using other technologies (satellite, cable, etc.). The environment includes natural hazards (e.g., earthquakes, hurricanes, and storms) that create operations risk.

Since the company is publically owned, the board of director’s primary objective is to increase shareholder value. Stakeholders have many complementary and conflicting objectives. For example, the board may want to increase revenues and profits; the leadership may want to increase executive compensation; the sales department may want to increase the number of subscribers; the network operators want to increase availability and reduce dropped calls; the safety office may want to decrease accidents; the technologists may want to develop and deploy the latest generation of network communications; the cell phone manufacturers may want to sell improved technology cell phones; companies that sell the cell phones and services may want to increase their profit margins; operations managers want to reduce the cost of operations; the human resources department may want to increase diversity; and the employees may want to increase their pay and benefits.

7.2.2 GOVERNMENT AGENCY EXAMPLE

Next, consider a government agency that operates a large military communications network involving many organizations. There are no shareholders in this public system that provides communications to support military operations. However, like the private company example, there are many stakeholders. Some of the key stakeholders are the Department of Defense (DoD) office that establishes the communications requirements and submits the budget; Congress who approves the annual budgets for the network; the agency that acquires the network; the agency that manages the network; the contractor personnel who manufacture and assemble the network; the contractor, civilian, and/or military personnel who operate the network; the information assurance personnel who maintain the security of the network; the mission commanders who need the network to command and control their forces; and the military personnel whose lives may depend on the availability of the network during a conflict. The environment includes natural hazards (e.g., earthquakes, hurricanes, and storms) that create operations risk. Instead of business competitors, the network operators face determined adversaries who would like to penetrate the network to gain intelligence data in peacetime or to disrupt the network during a conflict.

The stakeholders have many complementary and conflicting objectives. For example, the DoD network management office wants the best network for the budget; Congress wants an affordable communications network to support national security; the acquiring agency wants to deliver a network that meets the requirements, on time and on budget; the network management agency wants to insure an adequate budget; the contractors want to maximize their profits and obtain future work; the network operators want to increase network capabilities and maximize availability of the network; the information assurance personnel want to maximize network security; the mission commanders want to maximize the probability of mission success; and the military personnel who use the network want to maximize availability and bandwidth.

7.3 Challenges in Identifying Objectives

The identification of objectives is more art than science. The four major challenges are (1) indentifying a full set of values and objectives, (2) obtaining access to key individuals, (3) differentiating fundamental and means objectives, and (4) structuring a comprehensive set of fundamental objectives for validation by the decision maker(s) and stakeholders.

In a complex decision, especially if it is a new opportunity for the organization, the identification of objectives can be challenging. In a research paper (Bond et al., 2008), Ralph Keeney and his colleagues concluded that “in three empirical studies, participants consistently omitted nearly half of the objectives that they later identified as personally important. More surprisingly, omitted objectives were as important as the objectives generated by the participants on their own. These empirical results were replicated in a real-world case study of decision making at a high-tech firm. Decision makers are considerably deficient in utilizing personal knowledge and values to form objectives for the decisions they face.” To meet this challenge, we must have good techniques to obtain the decision objectives.

A second challenge is obtaining access to a diverse set of decision makers (DMs), stakeholders (SHs), and subject matter experts (SMEs). In Chapter 5, we discuss the importance of using a decision process with access to the key decision makers. However, sometimes, clients are reluctant to provide the decision analysis team access to senior decision makers and diverse stakeholders who have the responsibilities and the breadth of experience that are essential to providing a full understanding of the decision objectives. In addition, it can be difficult to obtain access to the recognized experts instead of individuals who have more limited experience. Many times, the best experts resist meetings that take their focus away from their primary area of expertise. In addition, even if we have access, we may not have the time in our analysis schedule to access all the key individuals. To be successful, the decision analysis team must obtain access to as many of these key individuals as possible in the time they have allocated for the study.

The third challenge is the differentiation of fundamental and means objectives (R.L. Keeney, 1992). Fundamental objectives are what we ultimately care about in the decision. Means objectives describe how we achieve our fundamental objectives. An automobile safety example helps to clarify the difference. The fundamental objectives may be to reduce the number of casualties due to highway accidents and to minimize cost. The means objectives may include to increase safety features in the automobile (e.g., air bags and seat belts), to improve automobile performance in adverse weather (e.g., antilock brakes), and to reduce the number of alcohol impaired drivers (e.g., stricter enforcement). The mathematical considerations of multiple objective decision analysis discussed in Chapter 3 require the use of fundamental objectives in the value model.

The fourth challenge is structuring the knowledge about fundamental objectives and value measures that we obtain in an organized manner that makes it easy for decision makers, stakeholders, and experts to validate that the objectives and value measure form a necessary and sufficient set of measures to evaluate the alternatives

7.4 Identifying the Decision Objectives

7.4.1 QUESTIONS TO HELP IDENTIFY DECISION OBJECTIVES

The key to identifying decision objectives is asking the right questions, to the right people, in the right setting. Keeney (Keeney, 1994) has identified 10 categories of questions that can be asked to help identify decision objectives. These questions should be tailored to the problem and to the individual being interviewed, the group being facilitated, or the survey being designed.1 For example, the strategic objectives question might be posed to the senior decision maker in an interview, while the consequences question is posed to key stakeholders in a facilitated group.

7.4.2 HOW TO GET ANSWERS TO THE QUESTIONS

The four techniques to obtain answers to these questions and help identify objectives and value measures are research, interviews, surveys, and facilitated group meetings. Chapter 4 describes the key features of interviews, focus groups, and surveys in decision analysis and the best practices for using each technique. In this section, we discuss the use of these techniques to identify objectives.2 The amount of research, the number of interviews, the number and size of focus groups, and the number of surveys we use depends on the scope of the problem, the number of decision levels, the diversity of the stakeholders, the number of experts, and the time allocated to defining objectives and identifying value measures.

7.4.2.1 Research.

Research is an important technique to understand the problem domain; to identify potential objectives to discuss with decision makers, stakeholders, and experts; and to understand suggested objectives. The amount of research depends on the decision analysts’ prior understanding of the problem domain, knowledge of key terminology, and amount of domain knowledge expected of the decision analyst in the decision process. The primary research sources include the problem domain and the decision analysis literature. Research should be done throughout the objective identification process. Many times, information obtained with the other three techniques requires research to fully understand or to validate the objective recommendation.

7.4.2.2 Interviews.

Senior leaders and “world-class” experts can do the best job of articulating their important value and objectives. Interviews are the best technique for obtaining objectives from senior decision maker(s), senior stakeholders, and “world-class” experts since they typically do not have the time to attend a longer focus group or the interest in completing a survey. However, interviews are time consuming for the interviewer due to the preparation, execution, and analysis time. Since interviews are very important and take time, it is important to use the interview best practices we describe in Chapter 4.

7.4.2.3 Focus Groups.

Focus groups are another useful technique for identifying decision objectives. We usually think of focus groups for decision framing and product market research; however, they can also be useful for identifying decision objectives. While interviews typically generate a two-way flow of information, focus groups create information through a discussion and interaction between all the group members. As a general rule, focus groups should comprise between 6 and 12 individuals. Too few may lead to too narrow a perspective, while too many may not allow all attendees the opportunity to provide meaningful input. Chapter 4 provides best practices for group facilitation.

7.4.2.4 Surveys.

In our experience, surveys are not used as frequently to identify potential decision objectives as interviews and focus groups. However, surveys are a useful technique for collecting decision objectives from a large group of individuals in different locations. Surveys are especially good for obtaining general public values. Surveys are more appropriate for junior to mid-level stakeholders and dispersed experts. We can use surveys to gather qualitative and quantitative data on the decision objectives. A great deal of research exists on techniques and best practices for designing effective surveys. Chapter 4 provides a summary of the best practices.

7.5 The Financial or Cost Objective

The financial or cost objective may be the only objective, or it may be one of the multiple objectives. Shareholder value is an important objective in any firm. In many private decisions, the financial objective may be the only objective or the primary objective. Firms employ three fundamental financial statements to track value: balance sheet, income statement, and cash flow statement. In addition, firms commonly use discounted cash flow (net present value [NPV]) to analyze the potential financial benefits of their alternatives. For public decisions, the cost objective is usually a major consideration. The cost can be the full life cycle cost or only a portion of the costs of the alternative.

7.5.1 FINANCIAL OBJECTIVES FOR PRIVATE COMPANIES

In order to understand the financial objectives for private companies, we begin with the three financial statements. Next, we consider the conversion of cash flows to NPV.

7.5.1.1 Balance Sheet Statement.

A balance sheet is developed using standard accounting procedures to report an approximation of the value of a firm (called the net book value) at a point in time. The approximation comes from adding up the assets and then subtracting out the liabilities. We must bear in mind that the valuation in a balance sheet is calculated using generally accepted accounting principles, which make it reproducible and verifiable, but it will differ from the valuation we would develop taking account of the future prospects of the firm.

7.5.1.2 Income Statement.

The income statement describes the changes to the net book value through time. As such, it shares the strengths (use of generally accepted accounting procedures and widespread acceptance) and weaknesses (inability to address future prospects) of the balance sheet.

7.5.1.3 Cash Flow Statement.

A cash flow statement describes the changes in the net cash position through time. One of the value measures reported in a cash flow statement is “free cash flow” (which considers investment and operating costs and revenues, but not financial actions like issuing or retiring debt or equity). Modigliani and Miller (Modigliani & Miller, 1958) argue that the anticipated pattern of free cash flow in the future is a complete determinant of the economic value of an enterprise. Many clients are comfortable with this viewpoint; hence, a projected cash flow statement is the cornerstone of many financial decision analyses.

7.5.1.4 Net Present Value.

To boil a cash flow time pattern down to a one-dimensional value measure, companies usually discount the free cash flow to a “present value” using a discount rate. The result is called the NPV of the cash flow.

We usually contemplate various possible alternatives, each with its own cash flow stream and NPV cash flow. In many decision situations, clients are comfortable using this as their fundamental value measure. Chapter 9 provides information on building deterministic NPV models. Chapter 11 provides more information on analyzing the impact of uncertainty and risk preference. See Chapter 12 for a discussion of the choice of discount rate.

7.5.2 COST OBJECTIVE FOR PUBLIC ORGANIZATIONS

For many public organizations, minimizing cost is a major decision objective. Depending on the decision, different cost objectives may be appropriate. The most general cost objective is, subject to acceptable performance levels, to minimize life cycle cost, the full cost over all stages of the life cycle: concept development, design, production, operations, and retirement. However, costs that have already been spent (sunk costs) should never be included in the analysis. Since sunk costs should not be considered and some costs may be approximately the same across alternatives, in practice, many decision analysts consider the delta life cycle costs among the alternatives. In public organizations, the budget is specified by year and may or may not be fungible between years. When multiple years are analyzed, a government inflation rate is used to calculate net present cost.

7.6 Developing Value Measures

In order to quantitatively use the decision objectives in the evaluation of the alternatives, we must develop value measures for each objective that measure the a priori potential value, that is, before the alternative is selected. The identification of the value measures can be as challenging as the identification of the decision objectives. We can identify value measures by research, interviews, and group meetings with decision makers, stakeholders, and subject–matter experts. Access to stakeholders and experts with detailed knowledge of the problem domain is the key to developing good value measures.

Kirkwood (Kirkwood, 1997) identifies two useful dimensions for value measures: alignment with the objective and type of measure. Alignment with the objective can be direct or proxy. A direct measure focuses on attaining the full objective, such as NPV for shareholder value. A proxy measure focuses on attaining an associated objective that is only partially related to the objective (e.g., reduce production costs for shareholder value). The type of measure can be natural or constructed. A natural measure is in general use and commonly interpreted, such as dollars. We have to develop a constructed measure, such as a five-star scale for automobile safety. Constructed measures are very useful but require careful definition of the measurement scales. In our view, the use of an undefined scale, for example, 1–7, is not appropriate for decision analysis since the measures do not define value and scoring is not repeatable.

Table 7.1 reflects our preferences for types of value measures. Priorities 1 and 4 are obvious. We prefer direct and constructed to proxy and natural for two reasons. First, alignment with the objective is more important than the type of scale. Second, one direct, constructed measure can replace many natural and proxy measures. When value models grow too large, the source is usually the overuse of natural, proxy measures.

TABLE 7.1 Preference for Types of Value Measure

| Type | Direct Alignment | Proxy Alignment |

| Natural | 1 | 3 |

| Constructed | 2 | 4 |

7.7 Structuring Multiple Objectives

Not all problems have only the financial or the cost objective. In many public and business decisions, there are multiple objectives and many value measures. Once we have a list of the preliminary objectives and value measures, our next step is to organize the objectives and value measures (typically called structuring) to remove overlaps and identify gaps. For complex decisions, structuring objectives can be quite challenging. In this section, we introduce the techniques for identifying and structuring, using hierarchies. The decision analysis literature uses several names: value hierarchies, objectives hierarchies, value trees, objective trees, functional value hierarchy, and qualitative value model.

7.7.1 VALUE HIERARCHIES

The primary purpose of the objectives hierarchy is to identify the objectives and the value measures so we understand what is important in the problem and can do a much better job of qualitatively and quantitatively evaluating alternatives (see Chapter 9). Most decision analysis books recommend beginning with identifying the objectives and using the objectives to develop the value measures. For complex decisions, we have found that it is very useful to first identify the functions that create value that the solution must perform (Parnell et al., 2011). For each function, we then identify the objectives we want to achieve for that function. For each objective, we identify the value measures that can be used to assess the potential to achieve the objectives. In each application, we use the client’s preferred terminology. For example, functions can be called missions, capabilities, activities, services, tasks, or other terms. Likewise, objectives can be called criteria, evaluation considerations, or other terms. Value measures can be called any of the previously mentioned terms (see Chapter 3).

The terms objectives hierarchy and functional value hierarchy are used in this book to make a distinction between the two approaches. The functional value hierarchy is a combination of the functional hierarchy from systems engineering and the value hierarchy from decision analysis (Parnell et al., 2011). In decisions where the functions of the alternatives are the same, or are not relevant, it may be useful to group the objectives by categories to help in structuring the objectives.

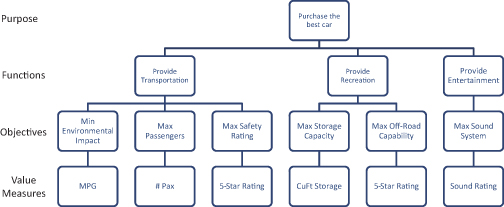

Both hierarchies begin with a statement of the primary decision objective as the first node in the hierarchy. An objectives hierarchy begins with the objectives in the first tier of the hierarchy, (sometimes) subobjectives as the second tier and value measures as the final tier of the hierarchy (see Fig. 7.1). A functional value hierarchy uses functions as the first tier, (sometimes) subfunctions as the second tier, objectives as the next tier, and value measures as the final tier of the hierarchy (see Fig. 7.2).

FIGURE 7.1 Objectives hierarchy for car purchase.

FIGURE 7.2 Functional value hierarchy for car purchase.

In the car purchase case illustrated in Figures 7.1 and 7.2, the objectives and value measures are the same in both hierarchies. However, in our experience, this is seldom the case. A more typical case is shown in Figure 7.3. When the randomly ordered objectives hierarchy is logically organized by functions, the objectives and measures make more sense to the decision makers, and, many times, we identify missing objectives (and value measures). The benefit of identifying the functions is threefold. First, a logical structure of the functional objectives hierarchy is easier for the decision analyst to develop. Second, it may help identify additional objectives (and value measures) that might be missed in the objectives hierarchy. Third, the logical order helps the decision makers and stakeholders understand the hierarchy and provide suggestions for improvement.

FIGURE 7.3 Comparison of objectives and functional objectives hierarchy.

In either the value hierarchy or functional hierarchy, we can create the structure from the top down or from the bottom up. Top-down structuring starts with listing the fundamental objectives on top, and then “decomposing” into subobjectives until we are at a point where value measures can be defined. It has the advantage on being more closely focused on the fundamental objectives, but often, we initially overlook important subobjectives. Bottom-up structuring starts by discussing at the subobjective or subfunctional level, grouping similar things together, and defining the titles at a higher level for the grouped categories. Value measures are then added at the bottom of the hierarchy. It has the advantage of discussing issues at a more concrete and understandable level, but if we are not careful, we may drift from the fundamental objectives in an attempt to be comprehensive. In theory, both approaches should produce the same hierarchy. In practice, this rarely happens. Our experience has shown that top-down structuring is easier for the novice, while bottom-up structuring, with the guidance of an experienced decision analyst, provides a better understanding of the levels where trade-offs are actually being made.

7.7.2 TECHNIQUES FOR DEVELOPING VALUE HIERARCHIES

The credibility of the qualitative value model is very important in decision analysis since there are typically multiple decision-maker and stakeholder reviews. If the decision makers do not accept the qualitative value model, they will not (and should not!) accept the quantitative analysis. We discuss here four techniques for developing objectives that were developed by the first author and his colleagues: the platinum, gold, silver, and combined standards.

7.7.2.1 Platinum Standard.

A platinum standard value model is based primarily on information from interviews with senior decision makers and key stakeholders. Decision analysts should always strive to interview the senior leaders (decision makers and stakeholders) who make and influence the decisions. As preparation for these interviews, they should research potential key problem domain documents and talk to decision-maker and stakeholder representatives. Affinity diagrams (Parnell et al., 2011) can be used to group similar functions and objectives into logical, mutually exclusive, and collectively exhaustive categories. For example, interviews with senior decision makers and stakeholders were used to develop a value model for the Army’s 2005 BRAC value model (Ewing et al., 2006).

7.7.2.2 Gold Standard.

When we cannot get direct access to senior decision makers and stakeholders, we look for other approaches. One approach is to use a “gold standard” document approved by senior decision makers. A gold standard value model is developed based on an approved policy, strategy, or planning document. For example, in the SPACECAST 2020 study (Burk & Parnell, 1997), the current U.S. Space Doctrine document served as the model’s foundation. In addition, environmental value models have been directly developed from the Comprehensive Environmental Restoration and Liability Act (Grelk et al., 1998). Many military acquisition programs use capability documents as a gold standard since the documents define system missions, functions, and key performance parameters. Many times, the gold standard document has many of the functions, objectives, and some of the value measures. If the value measures are missing, we work with stakeholder representatives to identify appropriate value measures for each objective. It is important to remember that changes in the environment and leadership may cause a gold standard document to no longer reflect leadership values. Before using a gold standard document, confirm that the document still reflects leadership values.

7.7.2.3 Silver Standard.

Sometimes, the gold standard documents are not adequate (not current or not complete) and we are not able to interview a significant number of senior decision makers and key stakeholders. As an alternative, the silver standard value model uses data from the many stakeholder representatives. Again, we use affinity diagrams to group the functions and objectives into mutually exclusive and collectively exhaustive categories. For example, inputs from about 200 stakeholders’ representatives were used to develop the Air Force 2025 value model (Parnell et al., 1998). This technique has the advantage of developing new functions and objectives that are not included in the existing gold standard documents. For example, at the time of the study, the Air Force Vision was Global Reach, Global Power. The Air Force 2025 value model identified the function, Global Awareness (later changed to Global Vigilance), which was subsequently added to the Air Force Vision of Global Vigilance, Reach, and Power.

7.7.2.4 Combined Standard.

Since it is sometimes difficult to obtain access to interview senior leaders, and many times key documents are not sufficient to completely specify a value model, the most common technique is the combined standard. First, we research the key gold standard documents. Second, we conduct as many interviews with senior leaders as we can. Third, we meet with stakeholder representatives, in groups or individually, to obtain additional perspectives. Finally, we combine the results of our review of several documents with findings from interviews with some senior decision makers and key stakeholders and data from multiple meetings with stakeholder representatives. This technique was used to develop a space technology value model for the Air Force Research Laboratory Space Technology R&D Portfolio (Parnell et al., 2004), the data center location decision we use for the data center illustrative example, and many other value models.

7.7.3 VALUE HIERARCHY BEST PRACTICES

The following are some recommended best practices for developing value hierarchies using any of the above four techniques:

- Put the problem statement at the top of the hierarchy in the language of the decision maker and key stakeholders. A clear problem statement is a very important tool to communicate the purpose of the decision to the decision maker(s), senior stakeholders, and the decision analyst team.

- Use fundamental objectives and not means objectives in the hierarchies.

- Select terms (e.g., functions, objectives, and value measures) used in the problem domain. This improves understanding by the users of the model.

- Develop functions, objectives, and value measures from research and stakeholder analysis.

- Carefully consider the use of constraints (screening criteria) in development of your objectives and value measures. Constraints can create objectives and value measures. However, as we discuss in the next chapter, the overuse of constraints can reduce our decision opportunities.

- Logically sequence the functions (e.g., temporally). This provides a framework for helping decision makers and stakeholders understand the value hierarchy.

- Define functions and objectives with verbs and objects. This improves the understanding of function or objective.

- Identify value measures that are direct measures of the objectives and not proxy measures. Proxy measures result in more measures and increased data collection for measures that are only partially related to the objectives.

- Vet the value hierarchy with decision makers and stakeholders.

7.7.4 CAUTIONS ABOUT COST AND RISK OBJECTIVES

Two commonly used objectives require special consideration: the cost and risk objectives.

7.7.4.1 Cost Objective.

Mathematically, minimizing cost can be one of the objectives in the value hierarchy and cost can be a value measure in the value model. However, for many multiple objective decisions (especially portfolio decision analysis in Chapter 12), it is useful to treat cost separately and show the amount of value per unit cost. In our experience, this is the approach that is the most useful for decision makers who have a budget that they might be able to increase or they might have to accept a decrease.

7.7.4.2 Risk Objective.

Risk is a common decision making concern, and it is tempting to add minimization of risk to the set of objectives in the value hierarchy. However, this not a sound practice. A common example is helpful to further explain why we do not recommend this approach. Suppose there are three objectives: maximize performance, minimize cost, and minimize time to complete the schedule. It may be tempting to add minimize risk as a forth objective. But what type of risk are we minimizing and what is causing the risk? The risk could be performance risk; cost risk; schedule risk, performance and cost risk; cost and schedule risk; performance and schedule risk; or performance, cost, and schedule risk. In addition, there could be one or more uncertainties that drive these risks. In Chapter 11, we introduce probabilistic modeling to model the sources of risk and their impact on the value measures and the objectives. We believe this is a much sounder approach than the use of a vague risk objective in the value hierarchy.

There is also a more basic reason why adding a risk objective is not sound. To make decisions that are consistent with the Five Rules of decision analysis (see Chapter 3), risk-taking preferences should be handled via a utility function that maps value outcomes to the utility metric. Therefore, making the level of risk one of many components in the calculation of overall value is not a “best practices” approach. See Chapter 11 for a full discussion of how risk should be treated in decision analysis.

That said, if circumstances dictate that risk must be part of the value hierarchy, Phillips proposes an interesting approach for representing probabilities as preferences such that they can used in an additive multicriteria model (Phillips, 2009). He suggests including a “confidence” criterion, assessing probabilities, and converting them to preference scores (or “expected values”) using a “proper scoring rule.” A proper scoring rule, due to its formulation, encourages an expert to report states of uncertainty accurately in order to avoid severe penalties for misassessments. If the expert, such as a weatherman, judges a probability to be high and this turns out to be correct, he is given a low penalty score. But whatever his state of uncertainty, he can also minimize the penalty score by expressing his uncertainty accurately when reporting it as a probability. One such proper scoring rule uses a logarithmic rule in which the score for a probability p is proportional to log10p. The logarithmic nature of the scale ensures that scores for compound events can be derived by summing scores associated with the component events. The expected score associated with an inaccurate report of uncertainty is always worse than the expected score for the expert’s real belief. Surprisingly, this statement is true whatever the expert’s true belief. In the long run, the penalty will be minimized by reporting accurately. It also provides an audit trail enabling different assessors to be compared after many assessments have been made. The person with the lowest total penalty is both knowledgeable about the events in question, and is good at reporting their uncertainty accurately. The major purpose of using the proper scoring rule is to make it easier to obtain unbiased assessments. While the authors believe that there can be value in using this approach under certain circumstances, we believe that the best practice is to directly assess probabilities and use them in an expected value or expected utility calculation rather than converting probabilities to preferences.

7.8 Illustrative Examples

See Table 1.3 for further information on the illustrative examples. In this section, we review three very different approaches used to identify and structure the objectives used in the three illustrative examples.

7.8.1 ROUGHNECK NORTH AMERICAN STRATEGY (by Eric R. Johnson)

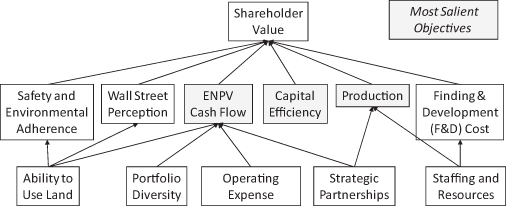

The decision frame for the Roughneck North American Strategy (RNAS) project is described in Chapter 6. The RNAS project used a means-ends objectives hierarchy (Fig. 7.4) to structure the objectives, which were identified using interviews and team meetings. The primary fundamental objective is shareholder value. The means–objectives hierarchy shows how the means objectives contribute to each other and the fundamental objective. The shaded means objectives were salient.

FIGURE 7.4 RNAS means–ends objectives hierarchy.

7.8.2 GENEPTIN (by Sean Xinghua Hu)

The decision frame for Geneptin is described in Chapter 6. To make the best decision for the development strategy of Geneptin, the product team used a dialogue decision process to involve senior decision makers and key stakeholders. As in most of pharmaceutical development and commercialization strategy decision making, the key metric the product team and company senior management used was economic value, as measured by the expected net present value (ENPV) of cash flow. Other metrics that are commonly of interest in the pharmaceutical industry, such as the probability of technical and regulatory success (PTRS) and investment level (i.e., drug development and launch costs), are used in the calculation of ENPV.

7.8.3 DATA CENTER LOCATION (by Gregory S. Parnell)

The decision frame for the data center problem is defined in Chapter 6. For the data center location decision analysis, we used the Combined Standard approach. We began by researching commercial data center technologies and trends. Second, we interviewed a large number of senior leaders and stakeholders. Third, we used a focus group meeting of stakeholder representatives to develop the functional value hierarchy.

The initial functional value hierarchy was developed in a 1-day focus group meeting of about 15 participants facilitated by a senior decision analyst. The following organizations were represented: mission; IT; data communications; facilities; security; power and cooling; program manager; systems engineering; and life cycle cost. The actual value model used about 40 value measures. For the illustrative example in this book, we use the most important 10 value measures (Fig. 7.5). We used the following approach.

FIGURE 7.5 Data center functional value hierarchy.

In Chapter 9, we describe the quantitative value model that was developed to evaluate the data center location alternatives.

An additional important objective was to minimize the life cycle cost. As part of our analysis, we developed a life cycle cost model that we used to evaluate each alterative data center location. However, we did not put life cycle cost in the functional value hierarchy. Instead, we plotted value versus cost to identify the nondominated alternatives (see Chapter 9).

7.9 Summary

Decision objectives are based on shareholder and stakeholder value. The crafting of the objectives and the value measures is a critical step in the decision analyst’s support to the decision maker and helps qualitatively define the value we hope to achieve with the decision. It is not easy to identify a comprehensive set of objectives and value measures for a complex decision. We describe the four techniques for identifying decision objectives: research, interviews, focus groups, and surveys. Research is essential to understand the problem domain and the decision analysis modeling techniques. Interviews are especially useful for senior leaders. Focus groups work well for stakeholder representatives. Surveys are especially useful to obtain public opinion. We note that the financial or cost objective is almost always an important objective. Next, we describe the important role of hierarchies in structuring objectives and providing a format that is easy for decision makers and stakeholders to review and provide feedback. We present objectives and functional hierarchies. We recommend functional value hierarchies for complex system decisions. Four techniques are useful for structuring objectives: Platinum (senior leader interviews), Gold (documents), Silver (meetings with stakeholder representatives), and Combined (using all three standards) Standards. The combined standard is the most common. The illustrative examples provide three very different approaches to identifying objectives.

KEY TERMS

Notes

1Our focus with these questions is the decision objectives. However, the answers may provide valuable insights on issues, alternatives, uncertainties, and constraints that can be used in later phases of the decision analysis.

2The techniques can also be used to obtain the functions and the value measures.

3Sometimes we do the sticky notes in four steps; screening criteria, functions, objectives, and value measures. However, our experience is that many participants do not clearly understand the distinctions between the four concepts at this stage of the analysis, so we get all their ideas and then label them.

REFERENCES

Bond, S., Carlson, D., & Keeney, R.L. (2008). Generating objectives: Can decision makers articulate what they want? Management Science, 54(1), 56–70.

Burk, R.C. & Parnell, G.S. (1997). Evaluating future space systems and technologies. Interfaces, 27(3), 60–73.

Charreaux, G. & Desbrieres, P. (2001). Corporate goverance: Stakeholder value versus shareholder value. Journal of Management and Governance, 5(7), 107–128.

Ewing, P., Tarantino, W., & Parnell, G. (2006). Use of decision analysis is the army base realignment and closure (BRAC) 2005 military value analysis. Decision Analysis, 3(1), 33–49.

Grelk, B.J., Kloeber, J.M., Jackson, J.A., Deckro, R.F., & Parnell, G.S. (1998 ). Quantifying CERCLA usiing site decision maker values. Remediation, 8, 87–105.

Keeney, R. (1994). Creativity in decision making with value-focused thinking. Sloan Management Review, 35, 33–34.

Keeney, R.L. (1992). Value-Focused Thinking: A Path to Creative Decision Making. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Kirkwood, C. (1997). Strategoc Multiple Objective Decision Analysis with Spreadsheets. Belmont, CA: Duxbury Press.

Modigliani, F. & Miller, M. (1958). The cost of capital, corporation finance and the theory of investment. American Economic Review, 48(3), 261–297.

Parnell, G.S., Conley, H., Jackson, J., Lehmkuhl, L., & Andrew, J. (1998). Foundations 2025: A framework for evaluating air and space forces. Management Science, 44(10), 1336–1350.

Parnell, G.S., Burk, R.C., Schulman, A., Kwan, L., Blackhurst, J., Verret, P., et al. (2004). Air force research laboratory space technology value model: Creating capabilities for future customers. Military Operations Reseach, 9(1), 5–17.

Parnell, G.S., Driscoll, P.J., & Henderson, D.L. (Trans.). (2011). Decision Making for Systems Engineering and Management, 2nd ed. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Phillips, L. (2009). Multi-criteria Analysis: A Manual. Wetherby: Department for Communities and Local Government.