CHAPTER OBJECTIVES

To introduce the basic economic choices that must be made in every society because of scarcity.

To describe differences among traditional, market, and planned economies, and how the basic economic choices are made in each of these systems.

To explain the basic philosophy, structure, and operation of market economies.

To explain why, where, and how government intervenes in mixed economies, chiefly the U.S. economy.

To evaluate the strengths and weaknesses of various economic systems.

To describe how economic systems relate to individual and collective economic decision making.

To explore the transition from planned to more market-oriented economic systems experienced in several major nations.

To consider the British foundations of the U.S. economy.

To highlight major historical periods in the United States that have shaped the U.S. economy.

Chapter 1 introduced the basic concept of scarcity that underlies the study of economics. No economy, no matter how large or sophisticated, can provide all the goods and services to satisfy every member's wants and needs. Thus, people in every economy must make decisions about what goods and services to produce, how to produce them, and who will receive the goods and services that are produced. In this chapter, we focus on these decisions and how they are made in different economies.

SCARCITY, THE BASIC ECONOMIC DECISIONS, AND ECONOMIC SYSTEMS

All economies continually produce goods and services, whether they are simple agricultural products or complex surgical equipment. The U.S. economy, for example, currently produces in excess of $15 trillion of cars, new construction, health care, and other goods and services over the course of a year. Unfortunately, even this seemingly huge output satisfies only part of people's wants and needs; the U.S. economy cannot satisfy every want.

How do we decide what collection of goods and services the economy will produce? How do we decide who gets what and how much they get? Why can some households buy steak while others can afford only hamburger? This economic predicament resembles the dilemma that Santa Claus faces—millions of cherubic boys and girls dreaming of endless toys but only one workshop, a few elves, and just one sleigh to carry the goodies. What does Santa put in his bag?

In every society, regardless of its wealth and power, certain choices about production and distribution must be made. Specifically, every society faces three basic economic decisions.

Basic Economic Decisions

The choices that must be made in any society regarding what to produce, how to produce, and to whom production is distributed.

- What goods and services to produce and in what quantities?

- How to produce goods and services, or how to use the economy's resources?

- Who gets the goods and services?

The first economic decision, what to produce, addresses the dilemma that every society's members voice endless wants but economies can produce only limited varieties and amounts of goods and services. As a result, in every society choices must be made about the types and quantities of goods and services to produce: Are cars or SUVs or trucks to be produced? How many? What models?

The second economic decision, how to produce goods and services, or how to use an economy's resources, reflects the reality that products can be made in any number of different ways, and different methods require different resources and processes. In producing cars, a company must decide what technology to use, how many workers to hire, whether to use sheet metal or plastic, and whether to add GIS systems and leather seats.

The third decision is a distribution issue: Who will get the goods and services produced? Who will receive the hybrid SUVs, running shoes, medical services, homes, and premium ice cream?

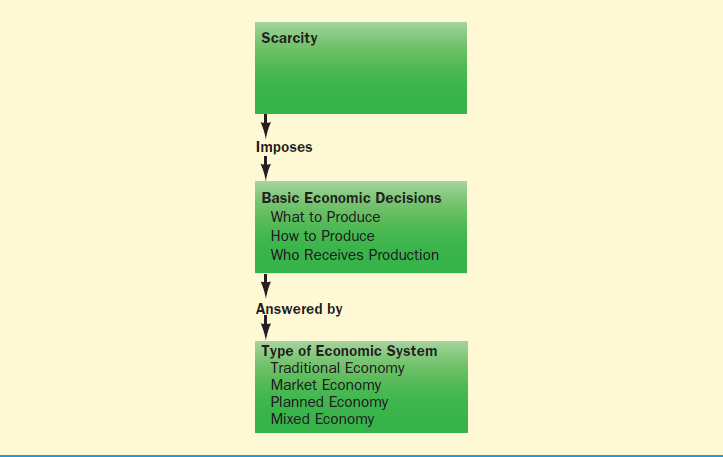

FIGURE 2.1 Scarcity, the Basic Economic Decisions, and Economic Systems

Scarcity imposes three basic economic decisions on a society. A society's economic system determines how the decisions are made.

Economic Systems and the Basic Economic Decisions

The way that a society makes the three basic economic decisions depends on its economic system. An economic system is a particular way of organizing the relationships among businesses, households, and the government to make basic choices about what goods and services to produce, how to produce them, and who will get them. Economists often classify economic systems into four types or models:

Economic System

The way in which an economy is organized to make the basic economic decisions.

- agrarian/traditional economies,

- market economies,

- planned or command economies, and

- mixed economies.

While today all economies are mixed economies, it is helpful to understand the basic model that underlies a particular mixed economy. Figure 2.1 summarizes the relationship among scarcity, the basic economic choices, and economic systems.

In traditional economies, decision making is based on custom or tradition. In market economies, individual buyers and sellers make the basic economic decisions as they communicate through prices in marketplaces. Planned, or command, economies emphasize collective decision making: Government planners represent economic participants. A mixed economy combines elements of planned and market economies.

TABLE 2.1 Strengths and Weaknesses of Traditional Economies

Traditional, or agrarian, economies have strengths and weaknesses.

TRADITIONAL OR AGRARIAN ECONOMIES

Most economies started out as traditional, or agrarian, economies. A traditional economy generally relies on tradition, custom, or ritual to decide what to produce, how to produce it, and to whom to distribute the results. As traditional economies outgrow simple traditional systems, they usually move toward market, planned, or mixed systems.

Traditional, or Agrarian, Economy

An economy that relies largely on tradition, custom, or ritual when making the basic economic decisions.

Economic Decisions in a Traditional Economy

Traditional economies rely on historical, social, political, or religious arrangements and traditions to decide what to produce. Typically, these economies are focused on some kind of agricultural commodity (like cotton, corn, or cattle) or mineral commodity (like copper). For example, some Native American tribes in the Southwest developed economies based on raising corn and sheep and then using the livestock for mutton and wool.

Traditional systems usually stay fairly small and rural, with economic decisions closely tied to hierarchies. These economies usually have work roles tied to traditional family and gender roles. Boys take up the occupations of their fathers, while girls stay close to their mothers. People use the same production methods that their families used for generations. Traditional economies often resist change and only slowly adopt new technologies. As a result, resources like land and labor are generally not very specialized, so traditional societies may not produce as much as they could if their resources were used more efficiently.

The decision of how to distribute goods and services is also made through tradition. Because these economies develop around hierarchies, what people get is often determined by their place in society. Those with a higher status, like landowners, may fare well, while others may not. However, agrarian societies sometimes work to support all members, at least at a subsistence level.

People in traditional economies often rely on barter—the direct exchange of goods or services for other goods or services—to meet their needs. Barter, by its very nature, is found in simple societies. As people's economic needs become complicated and varied, they inevitably need to create money to facilitate trade. This is one reason that traditional systems evolve into more developed economies.

Barter

The direct exchange of goods or services for other goods or services.

Table 2.1 summarizes the strengths and weaknesses of traditional economies.

MARKET ECONOMIES

A market economy is rooted in the belief that decisions are best made by individuals, or in a philosophy of individualism. In a market economy, individual buyers and sellers interacting in markets1 make the basic economic choices. Also called price systems, market economies rely on prices as the language through which buyers and sellers communicate their intentions. For example, Starbuck's expresses its intention to sell lattes by making them available at a particular price, and consumers tell Starbuck's that they want lattes by paying the price asked. The exchange of the latte is made because the price is suitable to both buyer and seller.

Market Economy

An economy in which the basic economic decisions are made by individual buyers and sellers in markets using the language of price.

Price System

A market system; one in which buyers and sellers communicate through prices in markets.

Essential to this system is private property rights, which give individuals and businesses the right to own resources, goods, and services, and to use them as they choose. In a pure market economy, individuals are free to form businesses, operate with a profit motive, and make their own decisions about price or product-related matters, or to engage in free enterprise.

Private Property Rights

Individual rights to possess and dispose of goods, services, and resources.

Free Enterprise

The right of a business to make its own decisions and to operate with a profit motive.

Pure market systems, where individual buyers and sellers make all economic decisions with no government intervention, have virtually disappeared. But price systems are extremely important for us to understand because they provide the philosophical and operational bases for economies like the U.S. market economy. The United States has kept the key features of a market economy, although it is more of a mixed system because of government's role.

Markets have existed in different types of economies throughout the history of the world. In some instances, markets have served simply as an allocation mechanism to aid people in making the basic economic decisions. For example, ancient Greece at the time of Aristotle featured intense trading despite the fact that the economy was, by current standards, primitive. Even planned economies have used markets in modern times to help allocate goods and services. For example, the former Soviet Union used markets even prior to the economic restructuring of the 1990s.

Market economies are usually associated with capitalism, an economic system in which private individuals own the factors of production and operate on a free-enterprise basis. Pure capitalist economies leave little room for government interference.

Capitalism

An economic system with free enterprise and private property rights; economic decision making occurs in a market environment.

The Operation of a Market Economy

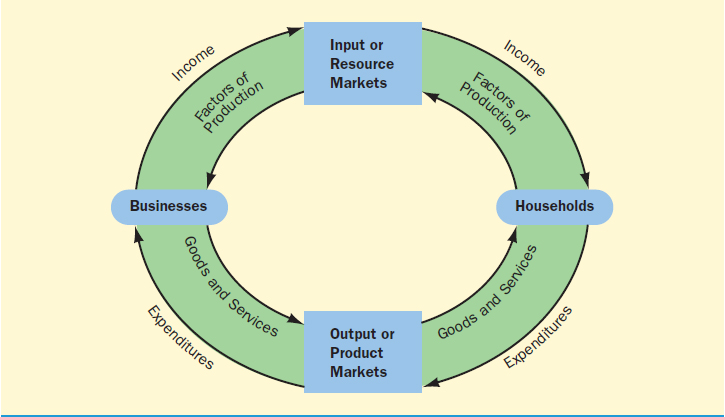

We can best illustrate the operation of a pure market economy with no government intervention by a circular flow model, such as that in Figure 2.2. This model shows how businesses and households relate to one another as buyers and sellers. In one part of this relationship, shown in the lower half of Figure 2.2, businesses are the sellers of goods and services and households are the buyers. Here there is a real flow of goods and services from businesses to households and a money flow of dollars from households to businesses. For example, sweaters, televisions, fajitas, and furniture flow to households, which give businesses dollars for these items.

Circular Flow Model

A diagram showing the real and money flows between households and businesses in output, or product, markets and input, or resource, markets.

Transactions of this type, where businesses sell goods and services and households buy them, occur in output markets, or product markets. In these markets, buyers and sellers may deal with one another face-to-face, as in automobile showrooms or restaurants, or through more impersonal negotiations, such as catalog orders, Internet purchases, or vending machines.

Output Markets (Product Markets)

Markets in which businesses are sellers and households are buyers; consumer goods and services are exchanged.

FIGURE 2.2 The Circular Flow of Economic Activity

Households sell factors of production to businesses in input markets, and businesses sell goods and services to households in output markets.

In the second part of the household–business relationship, businesses are the buyers and households are the sellers. Businesses need resources, or factors of production, which belong to households, to produce goods and services. In the upper half of Figure 2.2, a real flow of labor, capital, land, and entrepreneurship goes from households (sellers) to businesses (buyers). In return for these resources, businesses send a money flow of wages, interest, rents, and profits to households. For example, Ford Motor must hire machinists, design engineers, and line workers to produce vehicles. In return, these employees receive wages. Ford also pays dividends to its stockholders in return for their entrepreneurial role. Transactions involving resource purchases occur in input markets, or resource markets.

Input Markets (Resource Markets)

Markets in which households are sellers and businesses are buyers; factors of production are bought and sold.

A market economy's basic structure can be fully explained by focusing on the two buyer–seller relationships of businesses and households at the same time, or on Figure 2.2 as a whole. Businesses and households relate to one another through both input markets and output markets. Households sell labor, capital, land, and entrepreneurship to businesses in return for income in input markets. That income is then used to buy goods and services from businesses in output markets.

Economic Decisions in a Market Economy

How are the basic economic choices of what, how, and to whom made in a market system?

What to Produce? In a market economy, what and how many goods and services are produced is the result of millions of independent decisions by individual households and businesses in the marketplace. A business will produce something if it thinks that enough households will purchase the item at a price that will make its production profitable. If people do not want a good or service or will not pay a price that allows a profit, businesses will not produce that item. This is why some products like microwaves and the Ford Mustang continue to appear while some clothing styles and recording artists disappear from the market. New products such as Lego City and iPads emerge because individuals want them and businesses see profit opportunities in producing and selling them.

APPLICATION 2.1

SAYING NO!

SAYING NO!

Companies can exert great power in markets through the research, development, and introduction of products and their advertising and promotion. But, consumers also wield power through their decisions to purchase—or not purchase—a product. Over the years, there have been products brought to the market, sometimes by very large and well-known businesses, and consumers have rejected them. Here are a few examples.

The Edsel One of the most legendary misses on the auto market was Ford's Edsel, named after Henry Ford's only child. The Edsel was introduced in 1957 with great fanfare and expectations to sell more than 200,000 annually. But in 1958, its best year, barely 63,000 were sold. Its push-button gear shift on the center of the steering wheel and the horse-collar grill may have contributed to its demise. It was reported that the Edsel caused Ford to lose more than $300,000 a day before the announcement in November 1959 that production of this car would cease.

New Coke Coke drinkers around the country rebelled against the New Coke introduced by Coca-Cola in the mid-1980s. Even marketing campaigns could not assuage the anger of Coke drinkers who wanted the original taste to return. It took less than three months for the company to announce the return of the original formula—as Classic Coke.

Food Products The world of food products provides a plethora of examples of items that consumers said no to, sometimes despite substantial expenditures for product development and advertising. These include some interesting items. Colgate at one time introduced Kitchen Entrees—eat a Colgate meal then brush with Colgate tooth paste. Jimmy Dean's chocolate chip pancakes wrapped around a sausage on a stick disappeared. Kellogg's Breakfast Mates with cereal, milk, and a spoon didn't quite appeal to people who don't like room-temp milk on their cereal, and purple and green ketchup, frozen stuffing, garlic cake, aerosol spray toothpaste, and Dunk-a-Ball Cereal (designed to be something kids could play with before eating) are all gone from the market. Thirsty Dog, water for cats and dogs that was infused with flavors like beef and fish, also went away.

Football Two attempts were made to launch a new football league. The United States Football League (USFL) was introduced in 1983 to provide football during the spring and summer seasons with both ABC and ESPN contracting to televise games of the initial twelve teams. In 1985, the decision to bring the USFL into fall competition caused its collapse and the League played its last game in spring 1985. The XFL, another off-season football attempt, lasted for one season in 2001. The XFL was a joint venture of NBC and the World Wrestling Federation to allow a rougher, fewer rules game.

Other Near and Total Misses Harley-Davidson perfume didn't appeal to their loyal fans. The DeLorean car with its stainless steel exterior and wing doors saw a production of just 9,000. Smith and Wesson, the noted gun maker, couldn't transfer its appeal to the mountain bikes it decided to produce. Sony's Blu-ray eclipsed Toshiba's HD DVD. Microsoft's Zune has had a rocky existence. And the Segway Personal Transporter never reached its potential.

In a world of large corporate producers like car and cola companies, can individuals actually bring about product change? A single buyer acting alone may be powerless, but together consumers “vote” by virtue of spending or not spending their money on a product. Products disappear from the market when consumers do not buy them.2 Application 2.1, “Saying No!,” describes cases where consumers decided against a company's product.

TABLE 2.2 Costs of Different Methods for Producing a Guitar

Method 3 illustrates the least-cost method of production.

| Method of Production | Cost to Company per Unit |

| 1. Machine-assembled | $650.00 |

| 2. Hand-assembled | 900.00 |

| 3. Hand-and-machine-assembled | 530.00 |

How to Produce? In a market economy, businesses decide how to produce goods and services through their choices of production methods. Generally, a business can produce a good or service in more than one way, so businesses must decide which of the available techniques and resources or factors should be used for production. For example, suppose that a company identifies three different methods for producing a type of guitar: by machine, by hand, or by a combination of labor and machinery. The cost for each of the three methods is given in Table 2.2. Which method of production will the company choose in a market economy?

The company's owners will choose the least-cost method of production, or the most efficient method, as we discussed in Chapter 1. Since the owners' profit on the guitars is the difference between the product's price and its production costs, the lower the cost, the greater the profit. By using both labor and machinery (method 3), the company's owners stand to earn more profit than they would if they chose one of the other methods.

Least-Cost (Efficient) Method of Production

The method of production that allows a given good or service to be produced at the lowest cost.

In a market system, factor prices determine the most efficient production method, and are the basis for a firm's decisions about production techniques. In the United States, for example, agriculture is highly mechanized. Given the market prices of farm machinery and labor, and available technology, U.S. farmers find it cheapest to use more machinery and less labor to produce a given output. In other parts of the world, abundant and cheap labor encourages farmers to use production methods that emphasize human effort.

Who Gets Goods and Services? The price system determines who receives goods and services in a market economy. The circular flow model in Figure 2.2 shows a flow of goods and services going from businesses to households in output markets, matched by a flow of dollars going from households to businesses. In a market economy, people get goods and services only if they can pay for them. In other words, in a market economy, goods and services are distributed to those who can afford them.

In market systems, people earn money to buy goods and services by selling factors of production in resource markets. The amount and quality of labor, entrepreneurial skills, capital, or land that people sell determine the amount of income they have to spend on goods and services. People lacking marketable skills are not paid well in resource markets, so they cannot afford many goods and services. People who have many resources, or resources that are highly valued, may enjoy a substantial income, enabling them to buy the items they want in output markets. In a market system, people's abilities to purchase mountain cabins, original works of art, and cellars full of French wine—or peanut butter, one-room apartments, and bus tickets—are determined by the number and value of the resources they offer for sale.

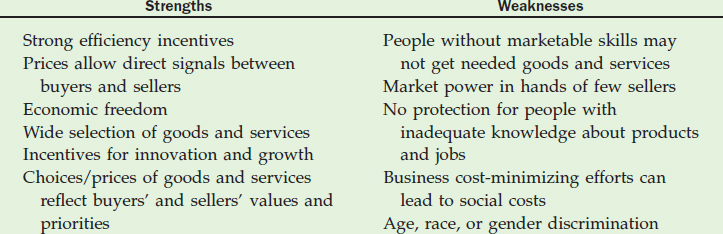

Evaluating Market Economies

Like all economic systems, market economies have both strengths and weaknesses.

Strengths: Efficiency, Consumer Choice, and the Opportunity for Success On the plus side, market economies tend to produce goods and services efficiently because profit and income act as incentives to guide production. Profit causes businesses to produce efficiently, and income incentivizes households to effectively use and improve their resources. Many students, for example, invest in education to become more productive and obtain higher salaries. (Table 15.5 provides data on the relationship between education and income.)

Market systems also encourage efficiency because the information required for production and distribution decisions passes directly between buyers and sellers via price. The market coordinates business and household actions, and through prices responds fairly quickly to their decisions.

Market systems also provide a wide range of choices in the variety and quality of goods and services for consumers. Market systems sometimes provide goods and services even before consumers realize that they want them. Market economies also offer significant opportunities for growth and change. Stories about the “local boy or girl makes good” abound in market systems. Many immigrants and Americans born into poverty have ascended the economic ladder through talent and hard work.

Weaknesses: Market Power, Equity, and Information There are several problems inherent in a market economy. Typically these are called market failures, a term economists use to describe problems created by a market-based system, or the inability of the system to achieve a society's goals.

Market Failure

A market system creates a problem for a society or fails to achieve a society's goals.

The competition at the foundation of a market economy can be lessened when competition drives out sellers and the market becomes dominated by one or a few sellers. When this happens, the interaction between buyers and sellers becomes lopsided, with undesirable consequences for buyers including higher prices, fewer choices, and less attention to quality. Consider an airport or stadium with just one food service: here people likely pay a high price and have fewer menu choices.

Market systems provide no protection for those who cannot provide for themselves. There is no means to acquire goods and services by people, such as the elderly, disabled, or children living in poverty, who cannot contribute to production. Pure market systems do not protect people who lack the knowledge to make informed decisions about purchases or employment. Market systems have no organized way to ensure that products offered for sale, such as medications and processed foods, or work environments are safe. The information required to assess every item a person could buy or the health and safety of a work place would be expensive, technical, and time consuming.

Market failure can also occur when age, race, or gender discrimination results in unequal treatment for some workers. Such discrimination leads to the inefficient use of labor resources.

Finally, market failure can result when the profit-driven, cost-minimizing efforts of businesses lead to costs that must be absorbed by all of society. Hazardous products, poor working conditions, or degradation of the environment could result from the efforts of producers to find less expensive means to operate. A hog farm that lowers its costs by allowing raw sewage to drain into a stream benefits through throwing some of its costs onto society. Table 2.3 summarizes the strengths and weaknesses of a market economy.

TABLE 2.3 Strengths and Weaknesses of Market Economies

A market economy has both strengths and weaknesses, which are termed market failures.

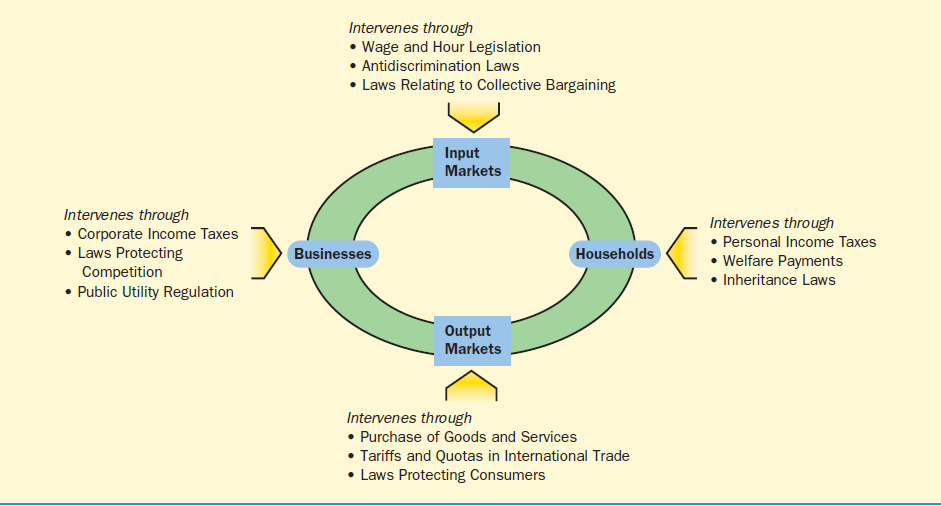

Government Intervention in a Market Economy: A Mixed Economy

Not surprisingly, society frequently turns to the government for help when it wants to address its economy's market failures. When government intervenes, the economy moves from its “pure” status to what we call a mixed economy. Figure 2.3 gives some examples of government intervention in the business sector, the household sector, output markets, and input markets when markets fail.

FIGURE 2.3 Government Intervention in a Market Economy

Government can intervene in a market economy in specific ways, as the examples illustrate.

There are some general ways in which government influences decision making.

- Government establishes the legal framework within which businesses and households operate. This involves the definition of property rights, contracts, standards of fair competition, court procedures, and other matters.

- While keeping business ownership in private hands, government sometimes intervenes through government regulation. Government commissions may oversee decisions that range from pricing, profit, and availability of service in certain industries, such as natural gas, to addressing specific problems, such as pollution and product safety, that cross many industries.

Government Regulation

Government commissions and boards are involved in business decision making. - Sometimes government intervenes in resource markets to protect workers and wages. Businesses must obey laws relating to the minimum wage, collective bargaining, worker health and safety, and other labor-related issues.

- Government taxing and spending policies influence inflation, unemployment, and the overall level of economic activity. The considerable size of some government expenditures, such as those in defense-related industries, affects certain markets.

- The U.S. government provides several income support programs such as Social Security, job-training programs, and Medicare payments for health care for older adults.

PLANNED ECONOMIES

A planned economy, also termed a command economy, is based on a philosophy of collectivism. In this type of economy, decisions are made by planning authorities, not by individuals. In this system, there are no private property rights. Rather, resources are owned collectively or by the government.

Planned Economy (Command Economy)

An economy in which the basic economic decisions are made by planners rather than by private individuals and businesses.

Government agencies, bureaus, or commissions may be the official planners in a planned economy. These economies allow no market activity and rely on extensive bureaucracies to make millions of detailed economic decisions and deal with the vast numbers of problems that invariably arise. Planned economies usually operate according to blueprints, termed plans, that establish general objectives, both economic and noneconomic, for the economy to accomplish over a period of time.

Today, few planned economies operate without some market orientation. As we move further into the twenty-first century, the large purely planned economies of the former Soviet Union and China are undergoing significant changes. The Soviet Union rushed into a quick abandonment of its planning system in the late 1980s and had problems adjusting to a new philosophy and institutional mechanisms. The Chinese, on the other hand, have adopted a slower, systematic approach to using market mechanisms.

Planned, or command, economies are often associated with socialism. In a socialist system, there may be no private property rights, since governments or collective groups of citizens officially own all resources. Socialist societies often attempt to make income distribution more equal among their members, at least in theory. A socialist system may depend heavily on planning or may, as in the case of market socialism, employ some planning but also rely heavily on markets.3

Socialism

An economic system in which many of the factors of production are collectively owned, and an attempt is made to equalize the distribution of income.

Economic Decisions in a Planned Economy

In planned economies, planning authorities decide what types and amounts of goods and services to produce. Planners use the planning objectives and their value judgments to determine how many submarines, corn silos, shoes, and other items the system will produce.

Government planners also decide how to allocate resources to produce goods and services. Here, the authority's influence is generally less direct and comes through determining which factors of production and processes will be made available to producers. For example, cars can be produced by manual labor or the use of robotics. If planners want to keep people employed, they will not plan for robotic equipment. In a purely planned economy, a producer cannot order a machine, part, or piece of equipment if the authority has not permitted it to be produced. Planners determine who will work in what jobs; how to use land, buildings, and productive equipment; and where economic opportunities lie.

Predictably enough, planning officials decide who will have access to goods and services. A rationing system may be used to distribute specific items or services, or planners may give individuals freedom to purchase what has been produced. If individuals can choose, then planners face the problem of income determination. That is, planners must decide how much income each production factor should be paid for its services.

Evaluating Planned Economies

What advantages do planned economies offer? These economies may achieve certain societal goals faster than in a less formally organized economy. The development of a high-tech industry or increased agricultural products might be accomplished more rapidly when a central authority coordinates efforts. Planned economies should also find it easier to eliminate unemployment when producers can simply be forced to use more labor in their processes. In addition, the ability to control the distribution of goods and services can alter shares in the economy's output. For example, a planning authority could ensure adequate heating fuel for all homes.

Just as market economies do not work perfectly, planned economics may experience planning failures when they create problems for a society or fail to achieve its goals. It is difficult for planned economies to match consumer wants and needs with production. The value judgments of planners about what to produce may not coincide with consumers' value judgments. Furthermore, the time lapse between a plan's creation and actual production may be so lengthy that items once considered desirable are no longer appropriate.

Planning Failure

Centralized planning creates a problem for a society or fails to achieve a society's goals.

The sheer complexity of production where government planners determine which resources, technology, and processes will be used creates issues. Shortages of a key resource can stop production. Mistakes and delays come with a slowed flow of information and decision making. With no incentives for producers or workers, the result can be inferior products and inefficient processes.

The environmental damage that can and has occurred with planning is a serious issue. In Eastern Europe and China, air and water pollution problems are consequences of planners' failures to take the environment into account in many of their decisions. Concerns about polluted air were a serious consideration for athletes who participated in the 2008 Summer Olympics in Beijing. Table 2.4 summarizes the strengths and weaknesses of a planned economy.

TABLE 2.4 Strengths and Weaknesses of Planned Economies

Planned economies have both strengths and weaknesses, called planning failures.

Test Your Understanding, “Economic Decision Making and the Circular Flow,” allows you to practice distinguishing among the different economic systems and to review the key relationships in a market economy.

MIXED ECONOMIES

Technically, all economies are mixed economies because the three basic choices are addressed by some combination of market and centralized decision making. Pure market and pure planned economies are polar cases that help us order our thinking but have no real-world counterparts. An important factor giving the different economies their unique styles is the manner and degree to which individual and collective decision making are combined. As discussed earlier, pure market and pure planned economies are not perfect. Market failures and planning failures cause the movement to mixed economies.

Mixed Economy

An economic system with some combination of market and centralized decision making.

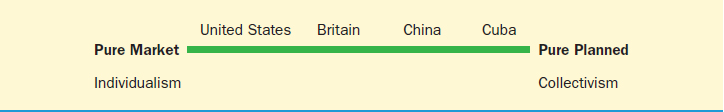

Figure 2.4 provides a helpful way to think about economic systems. With the exception of traditional economies, economic systems can be visualized as lying along a continuum. At one end are pure market economies, and at the other end are pure planned economies. The world's economies lie between these extremes and combine elements of market, or individual, decision making and planned, or collective, decision making. Where an economy falls on the continuum depends on its core philosophy about decision making and the degree to which it deviates from this core. For example, the United States lies closer to the market end of the continuum because of its reliance on markets, and Cuba lies closer to the planned end of the continuum because of its reliance on planning.

FIGURE 2.4 Continuum of Economic Decision Making

Economies can be classified according to their dependence on planned versus market decision making.

TEST YOUR UNDERSTANDING

ECONOMIC DECISION MAKING AND THE CIRCULAR FLOW

ECONOMIC DECISION MAKING AND THE CIRCULAR FLOW

- Indicate for each of the following situations whether it would most likely occur in a pure market economy, a pure planned economy, or a mixed economy.

- Businesses in a particular industry are free to produce however they want and are constantly on the lookout for new cost-reducing techniques since every dollar saved in cost is an extra dollar of profit.

- An economics instructor in a particular country does not bother to explain the circular flow model because it has no relevance to how the basic economic decisions are made in that country.

- Union and management representatives submit a deadlocked labor contract negotiation to the government for mediation.

- Workers who have lost their jobs and incomes cut back their spending because there is no alternative source of emergency financial support once their savings run out.

- Consumers are unable to obtain windshield wipers and tires for their cars because they are not being produced, yet accordions, which are plentiful and not in demand, continue to be produced.

- A catering business goes bankrupt, but its employees receive unemployment compensation while they look for other jobs.

- Suppose that, because of uncertainty about future jobs and incomes, households decide to increase their savings and reduce their current purchases of goods and services from businesses. With the aid of the circular flow diagram below, answer each of the following.

- Identify the flows on the bottom half of the circular flow model and explain what impact these household decisions will have on each of those flows.

- Identify the flows on the upper half of the circular flow model and explain what impact the actions taken on the bottom half of the model will have on the flows on the upper half.

- Based on the changes in the flows in the entire model, what should be the effect of this decision by households on future jobs and incomes?

Answers can be found at the back of the book.

UP FOR DEBATE

IS WESTERN-STYLE DEVELOPMENT APPROPRIATE FOR OTHER CULTURES?

IS WESTERN-STYLE DEVELOPMENT APPROPRIATE FOR OTHER CULTURES?

Issue People living in the United States and Western Europe enjoy high standards of living, especially compared to many other countries. Does this mean that policies that stimulate growth in the West will be just as effective for people living in other nations?

Yes Some experts believe the answer to this question is “yes” and recommend Western-style legal systems, political structures, and free markets as the basis for making the three economic choices. Societies that are rooted in individual choice and markets have strong economies, as demonstrated in much of the Western world, including the United States. Proof of this can be found by comparing indicators of economic well-being in Western-type economies with other economies. For example, the life expectancy is estimated to be over 78 years for a child born in 2011 in the United States, Germany, France, and most other Western European countries. The life expectancy for a child born in Angola, Nigeria, or Zimbabwe is fewer than 50 years. Also, while the estimated 2010 per capita GDP (adjusted for purchasing power parity) was over $35,000 for the United States, Canada, Sweden and others, the per capita GDP in Ukraine was $6,700 and for Haiti and Ethiopia it was less than $1,300.

In many Western nations free-market economic institutions have also helped to lead to political freedoms and democracy. A striking example of this is the conversion of some former Soviet-bloc countries to market capitalism as well as democratic political systems.

No Some experts argue that “grafting” Western institutions onto other nations, some of which have vastly different histories and cultures, may fail to improve living standards and may conflict with traditional cultural norms. For example, many former Soviet-bloc countries had little experience with political freedom and the institutions of free markets, and transplanting Western-style institutional structures did not result in Western-style growth. Inserting Western institutions into countries may force them to make hard decisions between the familiar social orders of the past and new political and economic freedoms.

Simply inserting Western-style institutions may not be enough to create healthy economic growth. In addition, the desirability of imposing Western values on non-Western nations can be questioned. Even the goal of economic development—with its emphasis on increasing output—can be controversial when it conflicts with very different collectively oriented value systems in many parts of the world. Some of the values that those living in Western-style economies take for granted—for example, the emphasis on consumerism and material progress—are themselves foreign to some other cultures.

Sources: Jasen Castillo, “The Dilemma of Simultaneity: Russia and Georgia in the Midst of Transformation,” World Affairs, June 22, 1997; Mike Dowling, http://www.Mrdowling.com/8oclife.html; U.S. Central Intelligence Agency, The World Factbook, http://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook,1/6/2012.

Up for Debate, “Is Western-Style Development Appropriate for Other Cultures?,” discusses whether the Western-style free-market system is the best road to development for traditional and nonmarket economies.

CHANGING ECONOMIC SYSTEMS

Since the mid-1980s, dramatic changes have occurred in many of the world's planned economies. The former Soviet Union, Poland, China, and other nations have been moving toward greater use of free markets and individual decision making. Described in terms of Figure 2.4, these and other planned economies have been shifting to the left along the continuum of economic decision making. In several of these countries, economic reform has been accompanied by greater political freedom. Non-Communist Party candidates have been elected to top positions in Russia, and several of the former Soviet republics, and China is slowly adopting some elements of choice associated with market economies.

An essential element for planned economies to move toward market economies is privatization. Individuals are granted property rights to factors of production that were once collectively owned or owned by the state. Without the protection of private ownership and the right to profit that it secures, individuals have few incentives to carry out the entrepreneurial functions—organizing resources and taking risks—that drive a market economy. Successful privatization is key to the actual transformation of a planned to a market economy.

Privatization

The granting to individuals of property rights to factors of production that were once collectively owned, or owned by the state.

The Realities of Economic Change

When it first became apparent in the late 1980s that the economic and political changes in Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union were real and that their closely controlled systems were disappearing, many people in the United States and other market-oriented countries felt a sense of unconditional victory. The free-market approach had won the ideological war, and all that remained was to watch the orderly transition from once-planned economies to more efficient market-based economies.

Problems in the transition, however, changed the initial sense of euphoria to guarded optimism. People lowered their expectations that the positive rewards of economic reform would come quickly. The transition experience taught us that, while the commitment to change may be professed quickly, change itself comes slowly.

The social, economic, and political institutions in Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union were the result of generations of living under a nonmarket ideology. These planned economies were deeply rooted in a philosophy of collectivism and had little familiarity with a philosophy of individualism. People in these planned economies were accustomed to direction from government officials, and individual initiative was rarely rewarded. Furthermore, there were those with vested interests in a planned system. All of this bred opposition to change.

Further transition problems arose from a shortage of readily available professionals to “set up” a market economy. This included business lawyers, entrepreneurs, and accountants, whose roles are taken for granted in market-based economies. Market economies also need laws relating to contracts, property rights, and commercial transactions. These types of laws and institutions simply didn't exist in societies that depended on government planners to carry out their economic affairs.

The rocky start to a market economy in Eastern European countries in the 1990s is evident in data. For example, from 1990 through 1999, prices of consumer goods and services purchased by Russian households increased by more than 1.3 million percent and by more than 22.7 million percent in Ukraine. In addition, output in Ukraine fell each year of the 1990s: Ukraine's total output in 1999 came to only 30 percent of what was produced in 1990.4

Today we watch China, a country of more than 1.3 billion people (the U.S. population is slightly more than 300 million) with a landmass slightly less than that of the United States, experience exceptionally rapid economic growth. Once considered to be a closed planned economy, China has moved slowly and carefully toward a more market-oriented system and has become an important player in world markets. China has quickly become a major consumer of energy and other resources, as well as the world's largest exporter. Application 2.2, “The People's Republic of China,” gives some background on changes in the economy of China.

APPLICATION 2.2

THE PEOPLE'S REPUBLIC OF CHINA

THE PEOPLE'S REPUBLIC OF CHINA

If you put China into your search engine, a huge number of sites for information will be identified. The World Factbook provides some basic demographic data and information, such as the geography, language, government, economy, and religions of China. Other sites provide historical and cultural information as well as political commentary.

For centuries, China stood as a leading civilization, outpacing the rest of the world in the arts and sciences, but in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, the country was beset by civil unrest, major famines, military defeats, and foreign occupation.

This huge country, which borders India, Pakistan, and Vietnam, among others, experienced a serious change in government after World War II. The Communists under Mao Zedong, better known as Chairman Mao, established an autocratic socialist system that, while ensuring China's sovereignty, imposed strict controls over everyday life and took the lives of tens of millions of people.

After 1978, Mao's successor Deng Xiaoping and other leaders began moving China from a centrally planned economy to a more market-oriented system. Reforms included the phasing out of collectivized agriculture, the gradual liberalization of prices, fiscal decentralization, development of stock markets, a push to grow the private sector and foreign trade, and more.

For much of the population, living standards have improved dramatically and the room for personal choice has expanded, yet political controls remain tight. China since the early 1980s has increased its global outreach and participation in international organizations. In 2010, China became the world's largest exporter. In 2011, the government adopted the Twelfth Five-Year Plan, which continues to reform the economy.

But, like other countries, China faces some serious problems. The one-child policy leaves China with one of the most rapidly aging countries in the world. Deterioration in the environment, especially air pollution from reliance on coal production, soil erosion, and the steady fall of the water table bringing water shortages along with a loss of arable land are other long-term issues.

Changes in China's economy and the impact it has on its own population as well as other world economies as it moves from a planned to a market-oriented system provide us with an interesting scenario to watch.

Source: United States Central Intelligence Agency, “China,” The World Factbook, April 15, 2008.

THE U.S. ECONOMIC SYSTEM

The U.S. economy has been described as a mixed economic system that largely depends on markets and individual decision making. The government plays a somewhat lesser but vitally important role in the U.S. system. We can trace the evolution of the U.S. economy into its present form by focusing on two important sets of developments: The first occurred in England and Scotland in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, and the second is based on major historical events in the United States.

The British Foundations of the U.S. Economy

When the early settlers, primarily from Britain, colonized the North American continent in the 1600s and early 1700s, the American colonies relied largely on agricultural commodities—notably cotton, tobacco, and corn—to trade for European necessities like tea, furniture, medicine, and industrial goods. As the American colonies developed more complex economic relationships, they faced the same dilemma that traditional or agrarian economies face: how to evolve into a more efficient and effective system.

The colonies relied on their British intellectual heritage and experience for guidance. The transformation of England and Scotland into market economies came from the rise of economic individualism in the late 1700s, and the British Industrial Revolution.

The Rise of Economic Individualism In 1776, a Scottish philosophy professor named Adam Smith (1723–1790) published a book entitled The Wealth of Nations. This book was to have a profound impact on economic thinking in his generation and future generations as well. Even today Adam Smith's book is frequently quoted.

Smith's thesis, put simply, was this: The best way to increase the wealth of a nation is through individual decision making with minimal government interference. The system he proposed, called laissez-faire (French for “let it alone”) capitalism, stood in sharp contrast to mercantilism, the then reigning economic philosophy. Mercantilism held that the state is the best judge of what is good for the economy. Mercantilist policies stood for the subordination of individual interests to the collective interests of the state and the belief that economic decisions should not be left to individuals acting in their own interest.

Laissez-Faire Capitalism

Capitalism with a strong emphasis on individual decision making; little or no government interference.

Mercantilism

An economic system or philosophy that subordinates individual interests and decisions to those of the state.

Central to Smith's argument for an economic system based on individual decision making was his invisible hand doctrine. According to this doctrine, it is foolish to expect people to base their business dealings with others on altruism or benevolence. Rather, people carry on their business in a way that serves their own best interests. But in a system of free and open competition where buyers have a wide range of businesses with which they can deal, it is in the producer's or seller's best interest to try to give the buyer what he or she wants on terms that are acceptable to both parties. In this way, Smith believed, by pursuing one's own best interest, one is guided “as if by an invisible hand” to advance the interests of all society. Government does not need to closely oversee the operation of the economy, since people working for their personal gain will achieve the most desired results.

Invisible Hand Doctrine

Adam Smith's concept that producers acting in their own self-interest will provide buyers with what they want and thus advance the interests of society.

Adam Smith's arguments and concepts provided an intellectual justification for an economic system based on individualism. Laissez-faire capitalism challenged both the government's role as economic director and the foundations of mercantilism as an economic philosophy. Both were crumbling in the face of a growing spirit of individualism in Britain and the colonies.

The British Industrial Revolution, 1750–1850 At the same time as the rise of economic individualism, significant technological and social changes were transforming England and Scotland into modern industrial economies. Known as the British Industrial Revolution, the British experience with industrialization served as a model for other countries that industrialized later, such as the United States.

Industrial Revolution

A time period during which an economy becomes industrialized; characterized by such social and technological changes as the growth and development of factories.

Prior to the mid-1700s, economic activity in Britain was primarily agricultural, and manufacturing processes—like weaving and metalworking—were carried on largely in simple cottage or home industries. Then a series of inventions and innovations began in the textile industry and spread to other industries. Inventions like massive mechanical weaving looms changed the emphasis of economic activity from agriculture and home production to a system fostering the growth of factories. With industrialization came many new and different products (such as the steam engine) as well as new production techniques (such as mass production and the factory system) that increased overall output. Great strides were made in providing goods and services.

Industrialization, however, had its dark side. Factory workers often experienced poor working conditions, low pay, and long hours. Factories often relied on the labor of women and children, who were easier to control than men and who would work for less. Perhaps not coincidentally, in 1818 Mary W. Shelley wrote about the threatening relationship between people and science in a work entitled Frankenstein. The poem “The Factory Girl's Last Day,” also written in the early 1800s and excerpted in Application 2.3, makes a strong statement about the factory system. What can you learn from the poem about the girl's age and her living and working conditions?

In summary, the British contributed to the U.S. economy in at least two ways. First, Adam Smith introduced a philosophical and intellectual defense of individualism and free enterprise that was to become a cornerstone of the U.S. and many other Western economies. Second, Britain experienced significant economic changes that illustrated both the benefits of capitalism and the problems that this system could create.

APPLICATION 2.3

THE FACTORY GIRL'S LAST DAY

THE FACTORY GIRL'S LAST DAY

The art and poetry of a particular time period often reflect the social attitudes of the day. Several poems written during the British Industrial Revolution make strong statements about the poor working conditions in factories. Below is an excerpt from “The Factory Girl's Last Day,” written in the early 1800s and attributed to various authors.

“‘Twas on a winter morning,

The weather wet and mild,

Two hours before the dawning

The father roused his child:

Her daily morsel bringing,

The darksome room he paced,

And cried: ‘The bell is ringing;

My hapless darling, haste!’

“‘Dear father, I'm so weary!

I scarce can reach the door;

And long the way and dreary:

O, carry me once more!’

Her wasted form seems nothing;

The load is on his heart:

He soothes the little sufferer,

Till at the mill they part.

“The overlooker met her

As to her frame she crept;

And with his thong he beat her,

And cursed her when she wept.

It seemed, as she grew weaker,

The threads the oftener broke;

The rapid wheels ran quicker,

And heavier fell the stroke.

“She thought how her dead mother

Blessed her with latest breath,

And of her little brother,

Worked down, like her, to death:

Then told a tiny neighbor

A half-penny she'd pay

To take her last hour's labor,

While by her frame she lay.

“The sun had long descended

Ere she sought that repose:

Her day began and ended

As cruel tyrants chose.

Then home! but oft she tarried;

She fell and rose no more;

By pitying comrades carried,

She reached her father's door.

“At night, with tortured feeling,

He watched his sleepless child:

Though close beside her kneeling,

She knew him not, nor smiled.

Again the factory's ringing

Her last perceptions tried:

Up from her straw bed springing,

‘It's time!’ she shrieked, and died!”

Source: Robert Dale Owen, Threading My Way (New York: Augustus M. Kelley, 1967), pp. 129–130. Original publication, 1874. Reprinted with permission.

Historical Highlights in the Development of the U.S. Economy

In the early history of the United States, the economy was closer to a pure market system, or laissez-faire capitalism, than it is today. Over the years the role and influence of government in the economy have grown, although the economy is still essentially market in nature. Several key events and historical periods are milestones in the movement of the U.S. economy from laissez-faire to its current status. These include the U.S. industrial boom, the New Deal and World War II era, the regulatory and deregulatory waves of the 1960s through 1990s, and recent developments.

The Industrial Boom Prior to the Civil War, the U.S. economy was primarily agricultural, with production in homes or small workshops and trade in local markets. In this environment laissez-faire was the prevailing system. But after the Civil War, through the early 1900s, significant changes occurred in U.S. economic and social life similar to those during the British Industrial Revolution. Growth in transportation and communications (primarily the railroads and telephone) opened new markets. New energy sources such as oil and electricity permitted mass production and the growth of a factory system. Great numbers of inventions introduced many new goods such as the light bulb, and more efficient farm machinery. People began to move from the farm to the city seeking work and greater opportunities. Immigrants from Europe came to the United States in droves seeking their fortunes in this new country where the rumor was that the “streets were paved with gold.”

Two problems developed in the midst of this industrial boom that would bring about government intervention. First, some businesses, such as Andrew Carnegie's U.S. Steel and John D. Rockefeller's Standard Oil, were becoming large and powerful corporations capable of monopolizing an entire market. Other companies were joining together with competitors to form trusts (as in the sugar and tobacco industries). Second, the living and working conditions for many Americans were becoming inordinately harsh. Many labored long hours for low wages in intolerable and dangerous conditions; child labor was permitted; city slums flourished; and attempts to form unions were often met with violence. As a result of these problems, significant legislation was passed that would alter the laissez-faire tradition.

In 1890, Congress, in an attempt to preserve a competitive landscape and prevent monopolies, passed the Sherman Antitrust Act that prohibits businesses from working together to restrain trade and from monopolizing or attempting to monopolize a market. The Sherman Act was followed in 1914 by the Clayton Act, which prohibits certain anticompetitive business practices, and the establishment of the Federal Trade Commission (FTC).

The living and working conditions experienced by many U.S. laborers were not changed by a single sweeping law; rather, improvement resulted from bits and pieces of new federal and state legislation that began in the early 1900s. The muckrakers, a group of authors, journalists, photojournalists, and others, stirred the public through their exposés of the harsh and dispiriting side of the industrial age. For example, Upton Sinclair, probably the best-known muckraker, wrote of conditions in the meat packing industry in The Jungle. The following excerpt shows the sensationalist manner in which Sinclair and other muckrakers wrote. It is no wonder that one response to this book was the Meat Inspection Act of 1907.

Muckrakers

Authors, journalists, and others who sensationalized American social problems in the early twentieth century.

This is no fairy story and no joke; the meat would be shovelled into carts, and the man who did the shoveling would not trouble to lift out a rat even when he saw one—there were things that went into the sausage in comparison with which a poisoned rat was a tidbit. There was no place for the men to wash their hands before they ate their dinner, and so they made a practice of washing them in the water that was to be ladled into the sausage. There were the butt-ends of smoked meat, and the scraps of corned beef, and all the odds and ends of the waste of the plants, that would be dumped into old barrels in the cellar and left there. Under the system of rigid economy which the packers enforced, there were some jobs that it only paid to do once in a long time, and among these was the cleaning out of the waste barrels. Every spring they did it; and … cart load after cart load of it would be taken up and dumped into the hoppers with fresh meat, and sent out to the public's breakfast.5

Other legislation of this period included the Food and Drug Act of 1906; state legislation limiting the hours and ages of working children; laws setting maximum hours and minimum wages for women; state workers' compensation insurance for injury on the job; and many other laws affecting matters that ranged from fire regulations to mandatory schooling.

Because of the antitrust legislation and consumer and worker regulations, by 1920 the government had established a precedent for intervening in economic activity, and the U.S. economy had moved away from laissez-faire capitalism.

The New Deal and World War II Era The stock market crash of 1929 signaled the beginning of the Great Depression—a severe economic decline that began in October 1929 and lasted for more than a decade. The Great Depression led to a series of programs and legislative reforms instituted during the presidential administration of Franklin D. Roosevelt and termed the New Deal.

New Deal

A series of programs and legislative reforms instituted during the administration of Franklin D. Roosevelt in the Great Depression of the 1930s.

These programs had various objectives. Some were designed to give substantial government aid to specific sectors of the economy. For example, to aid agriculture, farmers for the first time were paid not to grow crops and could seek government help for farm mortgage payments. To help the unemployed, agencies such as the Works Progress Administration (WPA) and the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) were established to provide jobs building public infrastructure such as bridges, roads, and schools, as well as in forestry and park work. Also, the Social Security Act was passed in 1935 to provide income for the aged, blind, and others.

Other programs were designed to regulate or bolster business activity and financial markets. The Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) was created to prevent fraudulent practices and to establish safeguards in securities markets. Banking was affected by several new programs, such as the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC). Also, in 1935 the National Labor Relations Act gave workers the right to bargain collectively.

In the Depression years the federal government began to run deficit budgets on a regular basis: It typically spent more than it received from taxes and other revenues. This practice was a break from the past and began a new direction in government budget policy. By the end of the 1930s, widespread government intervention in economic activity was part of U.S. capitalism.

The Great Depression came to an abrupt halt with the entry of the United States into World War II in December 1941. Because of the extent and magnitude of the war effort, many government agencies were instituted to oversee production, human resources, wages, prices, and such. Although most of these agencies were dismantled after the war, they did create a precedent for future reestablishment.

Following World War II, one of the most significant steps toward more government involvement in economic activity occurred with the passage of the Employment Act of 1946. This act gave the federal government the right and responsibility to provide an environment in which full employment, full production, and stable prices could be achieved. Under this act, Congress could now manipulate taxes and government spending and run deficit budgets in an effort to bring the economy to a desired level of activity. This meant that rather than influencing some specific part of the circular flow model (such as the input or output markets), government could influence the entire model. Such power had not been legislated before this period.

Employment Act of 1946

Legislation giving the federal government the right and responsibility to provide an environment for the achievement of full employment, full production, and stable prices.

The Regulatory and Deregulatory Waves Government intervention in the economy increased with a wave of regulatory activity that led to the creation of numerous federal agencies in the 1960s and 1970s. From 1964 through 1977, 25 such agencies were established, compared to only 11 during the Depression years of the 1930s. These agencies include the Environmental Protection Agency, the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, and the Consumer Product Safety Commission.

The regulatory trend of the 1960s and early 1970s was reversed, however, in the late 1970s and 1980s as the economy went through a wave of deregulation during the Carter and Reagan presidential administrations. Regulatory authority in various industries, such as commercial aviation, trucking, and natural gas, was reduced, and federal regulatory agency staffing began to decline in the early 1980s. Thus, in one sense, the role of government in economic activity was decreasing during this period.

Recent Developments How can we judge the direction of the government in economic activity in recent years? Are there predictors for future changes?

The deregulatory trend of the Carter and Reagan administrations was reversed during George H. W. Bush's administration with increased support for federal regulatory agencies and increased challenges of business mergers. But, more significantly, the government's impact on the economy increased with a dramatic rise in the federal public debt. In 1988, the federal debt was $2.6 trillion; by 2000 it had reached over $5.6 trillion. By 2012, the debt had grown to over $15 trillion. Chapter 6 deals with the size and impact of federal deficits and the debt on the economy.

In addition to the rising federal debt, other issues continue to dominate public attention: the cost of and payment for health care, regulation of banking and financial services, the environment, Social Security funding, Medicare funding, immigration, and more. The pressure to tackle some of these issues began with the Clinton administration when it became clear that a large population of aging boomers would put pressure on some of these areas. During the George W. Bush presidential administration there was a failed attempt to reform Social Security through privatization of investment decisions, but less government influence was won in some areas such as banking and food inspections.

With the election of Barack Obama as president there began a move toward more government intervention as the president and Congress began to tackle a serious economic downturn and failing banks and financial services companies. In addition, many environmental issues were moving to the forefront. The role of government increased with the bailouts of many companies in the auto and financial services industries.

Today there is a contentious atmosphere in Washington as various groups and parties weigh in on the role of government in economic activity. Some favor increased oversight by government in several arenas such as banking and consumer products; other favor a dismantling of government regulation and would revert toward a more laissez-faire system. The inability to reach compromise with respect for alternative opinions has left many Americans frustrated with the functioning of the federal government.

Summary

- All individuals and economies in the world experience scarcity; no economy can completely satisfy all of its members' wants and needs for goods and services.

- Because of scarcity, every society must make three basic economic decisions: what goods and services to produce and in what quantities; how to produce goods and services; and who gets the goods and services that are produced.

- Societies develop economic systems in order to deal with the three basic economic decisions. Societies usually evolve beyond traditional economies as they become more complex and move toward more formal economic systems, which we usually classify as market, planned, or mixed economies.

- Market economies rely on individual buyers and sellers to make the economic decisions. These systems are rooted in private property rights and free enterprise, and are usually associated with capitalism.

- In a market economy, buyers and sellers communicate their wants and needs through prices in markets. A market economy produces goods and services if buyers demand them at a price that allows sellers to produce them at a profit.

- In a market system, businesses produce goods and services efficiently by seeking least-cost production methods to maximize profits. The value of resources—land, labor, capital, and entrepreneurship—that individuals sell determines how many goods and services they can afford to buy.

- Economists use a circular flow model to illustrate the basic structure of a market economy. This model shows how businesses and households relate to one another as buyers and sellers in output and input markets.

- Market economies have advantages: They provide incentives to produce and use resources efficiently, allow direct communication between buyers and sellers, and reflect individual value judgments in production and distribution choices.

- Market economies have problems called market failures. They may leave the uninformed unprotected, allow discrimination among workers in input markets, not provide goods and services to those unable to contribute to production, foster monopolies, and create environmental problems.

- In a planned, or command, economy, government planners make the basic economic decisions. These systems are usually rooted in a philosophy of collectivism. Planned economies can allow societies to achieve noneconomic goals more easily, limit unemployment, and provide for a more equal distribution of goods and services. Planning failures may also arise: poor quality products, production stoppages, a lack of worker incentives, problems coordinating production with consumer choices, and pollution problems. Planned economies are often associated with socialism.

- Mixed economic systems combine elements of market and planned economies. Mixed economies arise in response to planning and market failures. Countries around the world fall on a continuum between pure market and pure planned economies: Pure types no longer exist.

- Since the late 1980s, the Soviet and other planned economies have moved toward greater dependence on markets and individual decision making, but the transitions have not been quick or problem free. In addition, China has experienced dramatic growth while carefully expanding some freedoms.

- The U.S. economy can be better understood by examining its British intellectual foundations and key developments in eighteenth- and nineteenth-century British history. These include the rise of a philosophy of individualism, which was advocated in Adam Smith's The Wealth of Nations, and the British Industrial Revolution.

- Important events in U.S. history that helped to shape the U.S. economy include the industrial boom following the Civil War; the Great Depression and World War II; the regulatory and deregulatory waves of the 1960s through the 1980s; and recent concerns over health care, Social Security, tax policy, the federal debt, national security, the environment, and other issues.

Key Terms and Concepts

Basic economic decisions

Economic system

Traditional, or agrarian, economy

Barter

Market economy

Price system

Private property rights

Free enterprise

Capitalism

Circular flow model

Output markets (product markets)

Input markets (resource markets)

Least-cost (efficient) method of production

Market failure

Government regulation

Planned economy (command economy)

Socialism

Planning failure

Mixed economy

Privatization

Laissez-faire capitalism

Mercantilism

Invisible hand doctrine

Industrial Revolution

Muckrakers

New Deal

Employment Act of 1946

Review Questions

- What are the three basic decisions every economy must make? Why must these decisions be made?

- How do traditional, market, planned, and mixed economies make the three basic economic decisions?

- Draw a simple circular flow diagram to illustrate the structure of a market economy. Include businesses and households, input and output markets, and real and money flows.

- Below are listed seven activities. Indicate whether each one is: a real flow through a product market; a money flow through a product market; a real flow through a resource market; or a money flow through a resource market.

- Receiving a paycheck at the end of each month

- Delivering a specially ordered hybrid car to a buyer

- Receiving patient care in a hospital

- Using a credit card to buy a meal in a restaurant

- Earning profit over the summer from your own ice cream stand

- Obtaining college credits

- Working overtime

- Identify three strengths of a market economy. Define and give a current example of a market failure.

- Identify the strengths and weaknesses of a planned economy. Explain what we mean by planning failure.

- What is the invisible hand doctrine and why is it important for laissez-faire capitalism? How did the British Industrial Revolution affect the way that the U.S. economic system developed?

- Indicate whether, and explain why, each of the following moved the U.S. economy closer to, or further away from, laissez-faire capitalism.

- The Sherman Antitrust Act of 1890, the Food and Drug Act of 1906, and the Meat Inspection Act of 1907

- The New Deal programs of the Roosevelt administration in the 1930s

- The regulatory reforms of the Carter and Reagan administrations

- Concern over global warming

- Privatization of defense functions during the George W. Bush war in Iraq

- Health care legislation during the Obama administration

Discussion Questions

- Suppose that you have been chosen to be on a blue-ribbon panel of experts to determine how well or poorly the economies of the world are operating. Your task is to come up with a checklist of five criteria by which different economies can be judged. Which five factors would you pick as criteria? Why?

- What considerations might cause one nation to choose to operate as a market economy and another as a planned economy?

- Many people today are asking what the U.S. government should do when people who need health care cannot afford it. Is less-than-universal access to health care an example of a market system allocating scarce resources efficiently, or is it an example of market failure?

- This chapter illustrates how economic systems change over time. What forces might lead to the evolution of an economic system, and how would these forces cause an economy to change?

- We noted in the text that the movement from a planned to a market economy was not smooth for the nations of Eastern Europe. What, in your opinion, was the biggest obstacle to this change, and why?

- Would mercantilism, the economic system that was important in Europe in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, be most consistent with a market economy, a planned economy, or a mixed economy? Do you know of any economic activity occurring at the present time that reflects a mercantilist philosophy?

- Based on your general knowledge of U.S. history and current events, how active a role do you think government will be playing in the economy 20 years from now, compared to the role it plays today?

- Environmental concerns are increasingly global as we realize that the careless use of the world's resources influences the entire globe. The impact of global warming, excessive energy use, and polluting rivers and streams is not confined to any one nation. What type of economic system do you think would best address environmental concerns? Will global concerns push more nations toward similar systems?

- Chapter 1 introduced the importance of efficiency and equity as they affect economic decisions. Discuss how each of the three basic decisions are related to efficiency and equity.

Critical Thinking Case 2

JUDGING ECONOMIES

Critical Thinking Skills

Getting to conclusions

Recognizing value judgments in decision making

Economic Concepts

Varied economic systems

Measuring standards of living

Familiarity with countries throughout the world has increased significantly. The emergence of easy, rapid communication, global travel opportunities, international corporations, the presence of large numbers of foreign students on U.S. college campuses, and much more have helped to expand our knowledge of each other's cultures and economies.

But, how do we judge the health of various economies throughout the world? If we were to step back and assess places like Russia, Indonesia, India, Japan, and Bhutan, how would we label their economies? How would we decide whether they are successful and growing or just the opposite?

Over the last half of the twentieth century, it was the “isms” that drove judgments about an economy: capitalism, communism, and socialism. There was a fundamental philosophical belief that issues like property rights and individual decision making formed the basis for judging an economy. Clashes among the “isms” went a long way toward explaining the Cuban Missile Crisis in the early 1960s and certainly the Vietnam War in the late 1960s and early 1970s.