Chapter 2

Check-in and related issues

Introduction

Some time normally elapses between the guest's booking and his actual arrival. During this period the hotel may deal with hundreds of other visitors. However, it must still be ready to receive the guest. There must be a room ready for him, and there are various necessary formalities to be gone through when he arrives.

In addition, the hotel must keep track of him once he is ‘in-house’. It may be required to provide him with various services, and it must make sure that these are properly recorded and (if appropriate) charged for.

All this means a good deal of record keeping. The process is summarized in Figure 19.

Arrival and registration

The arrivals list

The check-in process actually starts some time before the guest's arrival, for front office commonly makes out an arrivals list beforehand. This is a list of the arrivals expected on any specific date. Copies are circulated to the housekeeper, telephonist, head porter, food and beverage manager and possibly to the general manager (especially if any VIPs are expected).

The arrivals list is usually prepared twenty-four hours in advance, though group arrivals lists may be circulated up to a week beforehand (groups require rather more preparation). However, the list will not be completely accurate because:

![]() Some of the expected guests may turn out to be ‘no shows’.

Some of the expected guests may turn out to be ‘no shows’.

![]() There may well be some last minute (‘chance’) bookings.

There may well be some last minute (‘chance’) bookings.

The arrivals list is usually prepared from the bookings diary. The entries are rearranged so that they are in alphabetical order, and a note added if a room has been allocated in advance, a late arrival is expected or if there are any special requirements. The layout is typically as shown in Figure 20.

This process is time-consuming, and various short cuts have been devised, such as photocopying the Whitney advance booking rack. However, such expedients are not necessary with a computerized system, which can analyse information under as many different headings as necessary. The advance bookings can be listed according to date of arrival, for instance, and displayed on a VDU or printed off as an arrivals list.

Registration

When a guest arrives, he must be greeted politely and then asked to ‘register’. This means requesting him to put down certain particulars in a book or on a form. Registration serves three main functions:

1 It satisfies the legal requirements.

2 It provides a record of actual arrivals as opposed to bookings. The traditional justification for registration was that it provided some form of record in the case of a fire or other disaster. Since the register only shows arrivals, this was never wholly convincing. However, analysis of registration records can provide a useful market analysis.

3 It helps to confirm the guest's acceptance of the hotel's terms and conditions, and is thus useful should legal proceedings be necessary.

Registration also gives the guest something to do while the receptionist is checking her own records and perhaps deciding which room he should be allocated. Activities of this type fulfil a very useful social purpose, not least because they help to reassure the guest that his booking really is going to be honoured.

Legal requirements

These are at present to be found in the Immigration Order of 1972, which requires the hotelier to distinguish between non-aliens and aliens. Non-aliens are currently:

![]() British passport holders.

British passport holders.

![]() Commonwealth citizens.

Commonwealth citizens.

![]() Citizens of the Republic of Ireland (Eire).

Citizens of the Republic of Ireland (Eire).

![]() Members of NATO armed forces serving in the UK.

Members of NATO armed forces serving in the UK.

![]() Foreign nationals serving with the UK's armed forces.

Foreign nationals serving with the UK's armed forces.

![]() Foreign diplomats, envoys and their staff (this is under the Diplomatic Privileges Act 1964).

Foreign diplomats, envoys and their staff (this is under the Diplomatic Privileges Act 1964).

Any non-alien over sixteen years of age staying for one night or more is required to state his full name and nationality (notice that legally speaking this exempts short period ‘day lets’ from registration). The law does NOT require him to give his address, and it is well established (by custom and precedent) that the name he gives need not be his own, though he must not use a different one with intent to defraud.

The law does not require the guest to physically sign a register. This allows a husband to sign on behalf of his wife, or vice versa. Although both must be registered, it is permissible to do so on one line as ‘Mr and Mrs...’. This exemption also permits a tour guide or conference organizer to sign on behalf of a group of guests, though again each one must be separately registered. If hotels do ask guests to sign, it is to signify acceptance, and a signature is not compulsory, though few guests know this.

An alien is anyone who does not fall into the categories deemed to be non-alien. In addition to his name and nationality, such a guest is required to provide the following information:

![]() The number of his passport or registration certificate.

The number of his passport or registration certificate.

![]() Its place of issue.

Its place of issue.

![]() Details of his next destination, and, if possible, his address there.

Details of his next destination, and, if possible, his address there.

The purpose of this last provision is to enable the immigration authorities to keep track of visiting foreign nationals. It is seldom used in practice, but it does sometimes happen that the police will contact a hotel to find out if a particular individual has been staying there. If the guest is not sure where he is going next, you should ‘flag’ his bill so that the question can be put again when he is leaving. If all else fails, you might have to be content with the name of a town or region: at least that would show that you had done your best to get the information.

The law provides that registration particulars must be kept for a period of twelve months, and must be produced if requested by a police officer or Home Office representative.

Types of register

There are two basic types of register. The first is the registration book. It has the following advantages:

![]() It is compact, relatively cheap and difficult to lose.

It is compact, relatively cheap and difficult to lose.

![]() It is hard to alter without detection.

It is hard to alter without detection.

![]() It records arrivals in chronological order.

It records arrivals in chronological order.

On the other hand, it has certain disadvantages:

![]() It is very slow if there are large numbers of guests.

It is very slow if there are large numbers of guests.

![]() It lacks confidentiality (guests can see who else has arrived).

It lacks confidentiality (guests can see who else has arrived).

The balance of the factors tends to favour its use in the smaller, ‘family’ type of hotel. It typically looks like Figure 21.

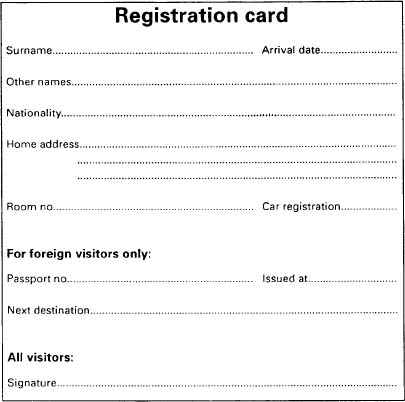

Large hotels find the registration book's lack of flexibility a major handicap, and generally use individual forms or cards. The layout of such registration cards varies from hotel to hotel, but they will generally include the items shown in Figure 22.

The advantages and disadvantages of the individual registration form mirror those of the book. It is rather more expensive and a great deal easier to lose. In theory, it would be easy to remove a card and insert a substitute (though this can be made more difficult by using serially numbered forms). However, cards are much more flexible, since they can be issued in batches to groups, even in advance, and you can even have dual-language cards for different nationalities (Japanese-English, for example). Moreover, they cannot easily be read by other guests.

Preregistration

It makes sense to try to complete as much of the registration process as possible in advance because this reduces delays at reception. This is common with group bookings because these often arrive all together and form an impatient queue at the desk.

What usually happens is that the reservations department receives a list of group names and room preferences from the group organizer several days in advance. Staff then prepare individual registration cards. On the day of arrival, rooms are allocated, their numbers added to the preprepared card, and room keys attached. The complete set is then placed in an envelope together with the group programme and hotel promotional material. When the group members arrive, they are directed to a separate desk, which is often set up in another room. There they are issued with their individual envelopes and asked to sign the preprepared registration card. This process clearly demands the use of cards rather than a book type register.

Computerized check-in

If the hotel is using a computerized system, it is usually possible to ‘call up’ the guest's booking particulars on the screen when he arrives, and continue the process from there. Obviously the computer must be ‘told’ that the guest has arrived, and there must be provision for any last minute changes. You will probably find that the program starts with something like the original booking screen (see Chapter 1), deleting some items which are no longer necessary (like expected time of arrival) and adding one or two others, such as the room allocated, any agreement regarding ‘extras’ (i.e. items to be charged to and paid for separately by ‘package’ guests) and the guest's credit limit (i.e. the amount he will be allowed to run up on credit before being asked to settle his account).

The resulting screen may look something like Figure 23.

Most of these fields will already have the details displayed, but they can be altered if necessary.

The procedure for checking in a ‘chance’ guest is very similar, except that here the fields will be empty and you will have to fill them in on the basis of the guest's responses.

Automated check-in

This is a relatively new development. It is now possible to install a machine rather like a bank cash dispenser which is able to handle arrivals and ‘chance’ bookings without any staff having to be present.

Such machines are usually activated by a credit card. If the guest has already made an advance booking, he will have quoted his card number when he did so. The machine is able to recognize this and display details of the booking for him to confirm. The machine can then display a personalized welcome and issue a computer-coded room key.

If the machine does not recognize the card number, it assumes that the owner is a ‘chance’ guest and displays a menu showing the rooms available and their rates. The guest chooses a suitable room and the machine goes on to display its personalized welcome and issue a computer-coded room key.

Sophisticated machines can also offer a range of other services for the guest to select, such as early morning teas and calls. They can also be programmed to turn on the heating and lighting in the room selected.

Such systems offer a number of important advantages:

1 They reduce costs. Maintaining twenty-four-hour coverage of the reception desk is expensive. Automated ‘after hours’ customer service is already common in other industries, and the same arguments apply to hotels. At the same time, the system reduces the number of errors caused by ‘operator fatigue’.

2 They can increase occupancy and room revenue. It is not unknown for bored, overtired or nervous night staff to simply ‘shut up shop’, even when there are still rooms available. The machine does not become bored, overtired or frightened.

3 They increase security. The hotel does not have to leave its front door open or maintain cash floats in the front office area overnight in order to deal with late check-ins. Only valid credit card holders can gain access legitimately, and while this does not guarantee immunity, it undoubtedly reduces the risks.

4 They can be moved closer to the customer. They could be placed on the street outside the hotel, for instance, or located at a distance (at the local airport, for instance).

The disadvantage is a reduction in the ‘hospitality’ element of the check-in process. Most present-day guests still prefer to be greeted by a cheerful, pleasant receptionist. However, automated check-in systems are likely to appeal increasingly to the computer-literate guests of the future, especially if they save them time.

The full implications as far as registration is concerned are not yet clear. As we have already pointed out, there is no legal requirement for a signature, and an electronic check-in record of the type we have just described may be sufficient as long as all the questions required by law were answered. The records would have to be retained for the required twelve-month period.

At the moment, however, ‘computer-assisted’ registration is the furthest most British hotels have been willing to go in this direction. This involves printing a computer-generated registration form prior to the guest's arrival. The details are taken from the original booking. The form is checked by the guest on arrival and the room number added. Until it is clear whether electronically stored records actually do satisfy the legal requirements, it is probably safer to run off a copy of the registration particulars in this way.

Room status records

It is necessary for a hotel to keep track of the current status of each room so that it can tell:

![]() If occupied, by whom, for how long, and for how much.

If occupied, by whom, for how long, and for how much.

![]() If unoccupied, whether it is available for letting, or not yet ready, or unavailable because it has been taken out of service for repairs or redecoration.

If unoccupied, whether it is available for letting, or not yet ready, or unavailable because it has been taken out of service for repairs or redecoration.

There are various ways of doing this.

Bed sheets

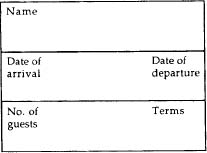

Some hotels have handled this requirement by keeping a loose-leaf record known as a ‘bed sheet’. This had preprinted pages which showed the rooms and their current letting position. A typical layout is shown in Figure 24.

The previous day's stays and arrivals were brought forward into the appropriate columns on the following day's sheet, using the ‘date of departure’ entry as a guide. Expected arrivals were added from the advance booking records, leaving the remainder available for letting. Chance arrivals were added to the sheet so that it provided an accurate record of the night's occupancy. Rooms out of service for various reasons could be noted as such.

This provided a written record of both occupancies and room revenue, but was labour-intensive.

Room racks

The ‘room rack’ or ‘reception board’ is found in most medium-sized hotels operating manual systems. It is simply a means of displaying the current letting position of every room in the hotel. Its relationship to the advance bookings chart must be clearly understood. The chart shows future bookings, and will be inaccurate because of no shows and chance arrivals. The room rack shows the situation now. It is the rack which acts as the basis for reports on occupancy and letting revenue. Consequently, it must be kept up to date and be completely accurate.

Room racks differ in detail from hotel to hotel, but the basic principle is always the same. There is some form of slot for each room, into which is placed a card or slip showing the current occupancy situation. Each slot is marked with the room number, and may carry other information as well, such as the current rack rate or a summary of its facilities.

Layouts vary, but the most common divides up the accommodation into floors, with adjacent rooms side by side so as to show any interconnections. The rack has to be located where the receptionists can consult it easily, but not where it is visible to guests.

The old-fashioned guest card was filled in with the basic details of the booking, as shown in Figure 25.

Other cards in different colours could be used to indicate:

![]() staff use

staff use

![]() being cleaned

being cleaned

![]() out of service

out of service

Providing this display was kept up to date, front office staff were able to tell the current occupancy situation at a glance.

Another variation on this theme was provided by the Whitney Corporation. This used a ‘ladder’ of metal slots, each exactly the right size to take a standard-sized Whitney slip. Each slot was labelled with the appropriate room number. Some models had perspex sleeves which could be slid across to tint the slip yellow, red or clear. These were used to indicate room status (e.g. yellow would indicate ‘on change’, red ‘reserved’ or ‘occupied’, and clear ‘available for letting’). This ‘traffic light’ system was taken even further by some large hotels, which fitted their room racks with coloured signal lights controlled jointly from front office and the housekeeper's office.

Computerized room status displays

The elaborate systems we have just described are now largely obsolete because the hotels which used them were among the first to install computers. A computerized system does the same job as the manual room rack, but the information is stored in an electronic memory rather than on a rack physically located in front office. This means that it can be consulted by anyone with authorized access to a keyboard and VDU, and changes can be made in the same way.

The computer keeps track of rooms through the registration process. It notes the rooms allocated and removes them from the list of those available for letting. When the guest checks out, the computer adds the room to the list of those to be cleaned. Once this has been done, the housekeeper enters the fact, and the computer immediately adds that room to the list of those available for letting. All this is done without the need to prepare separate cards or slips, which represents a considerable saving in clerical time.

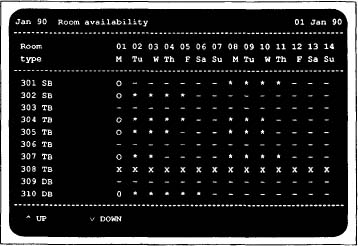

The computer will usually combine current room availability with an advance booking display so that you can see whether a particular room is likely to be needed over the next few days. In large hotels it will show blocks of rooms on a floor-by-floor basis with the facility to move ‘up’ or ‘down’. Typically, the display may look like that shown in Figure 26.

The conventions used may vary, but in this example ‘O’ means occupied, ‘*’ means allocated, ‘X’ means out of order and ‘-’ means vacant. Movement ‘up’ or ‘down’ is by cursor key.

Figure 26 Room availability display

Guest indexes

Manual indexes

The manual room rack shows who is in any particular room, but it is not always easy to find a particular guest's name, especially in very large hotels with high occupancies and a high turnover of visitors (imagine having to scan 500 slots, most of them filled with slips bearing guests’ names!). This made it necessary for such hotels to maintain an ‘alphabetical guest index’ of current guests with their accompanying room numbers. It was particularly useful to the telephonists, who had to know which room a guest had been allotted in order to put calls through to him.

The Whitney system was ideally suited for this purpose, since (as we have seen) it allowed slips to be inserted or removed at any point without disturbing the order of the other slips. The switchboard section in large non-computerized hotels commonly had their own alphabetically arranged Whitney rack. The slips were generally duplicates of those inserted in the room rack. In fact, front office staff usually made three or four copies, one for the room rack, another for the switchboard and a third and fourth for other departments. These last acted as arrivals notifications. When guests left, everybody had to remove their slips from the rack.

Of course, switchboard needs to supplement its guest index with other documents. Sometimes it receives calls for guests who are expected but who have not yet arrived, or who have already left. This means that the telephonists also need to have arrivals and departures lists to hand.

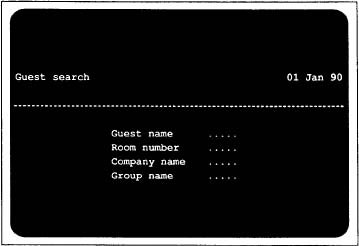

Computerized guest name search facilities

A computer can handle this type of query without any need for additional entries. It can give you room status information, or tell you which room a particular guest is in. Some search programs are very sophisticated in this respect, and can find near-equivalents to the name you have typed in. This is very useful if you haven't heard the caller distinctly or are not quite sure how the guest's name is spelled.

Typically, a program will present you with the alternatives shown in Figure 27.

The program will normally give you full details of all guests who meet the criteria selected, including their date of arrival, departure date, credit status and whether there are any messages waiting for them.

Room allocation

The room rack (or its computerized equivalent) is the basis for room allocation. It shows if there are rooms available, and whether they are actually ready for occupation. Although conventional charts allocate rooms when bookings are made, it is still necessary to check room status on arrival. The room might have been taken out of service unexpectedly or the current occupant may want to stay on for another night or so.

Even in modern, standardized hotels, some rooms are usually better than others. They might have a better view, for instance, or be further away from the lift. Guest preferences should be respected whenever possible, and room allocation should be conducted along the following lines:

1 VIPs should be allocated one of the best available. A note may have to be placed in the room rack to make sure that the room selected is not let to someone else.

2 Guests with special requirements (e.g. the disabled) should be treated in the same way.

3 Regulars, early bookings and long stays should be given priority in respect of the better rooms.

Some compromises will have to be made when applying these principles, but an experienced receptionist will quickly learn to ‘hold back’ a proportion of the better rooms for such arrivals.

Manual allocation can lead to problems. Receptionists tend to ‘favour’ certain rooms, often quite unconsciously. This means that some rooms can get far more usage than others, which makes any planned maintenance programme difficult to execute. Because of this, some hotels have tried to equalize room usage over the course of a year, either by instructing receptionists to maintain a room letting record, or by requiring them to let rooms in strict rotation. These attempts have not proved particularly successful.

However, it is perfectly feasible to assign room allocation to a computer, which will maintain its own record of room usage and make sure that all the rooms are used equally. This is clearly a good idea as long as it does not conflict with the guest's wishes. You would have to ensure that there was an ‘override’ facility allowing you to substitute your own choice for the computer's.

Guest in residence

Your responsibilities towards the guest do not end when he has been registered and allocated a room. Your main ongoing task is to make sure that his bill is kept up to date. This subject is dealt with in Chapter 4. However, there are a variety of other services which you may be required to perform. Individually these do not involve any particularly complicated procedures, but they still add up to a very important part of front office work.

Room changes

Sometimes a guest will want to change rooms during his stay. The hotel should agree wherever possible, because the guest's wishes must always come first. However, such alterations are potentially disruptive as far as the records are concerned, and they must be properly recorded.

The same principle applies to any rate changes (you might decide to make a reduction because of some deficiency in the facilities, for instance).

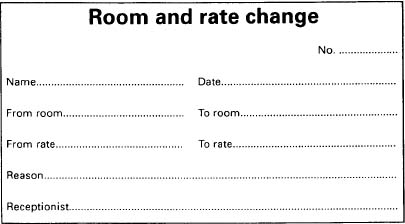

It is common to prepare a ‘room or rate change’ slip in such cases. This might be laid out as shown in Figure 28.

Copies would have to go to any department which had been notified of the original room or rate allocation (e.g. switchboard and the bill office). A copy would be retained as a record and added to the guest's file.

Most computerized systems will allow you to do this electronically, but there are still advantages in having a written record.

Key control

Traditionally, one of reception's main jobs has been to issue room keys to guests and then take them back for safe keeping when the guests went out. The keys had large and heavy tags attached to them to stop guests from walking off with them. The tags were numbered so that the key could be hung on a ‘key rack’ when not in use. The key rack was usually situated behind the desk.

The old-fashioned metal key was a security risk. Guests often lost or mislaid them, necessitating much rushing about with pass keys. Worse still, thieves could abuse the system by walking up to the desk during a busy period and asking for ‘Room 105’s key, please’ in a confident tone. Receptionists in a large hotel with a high turnover of visitors were not able to remember every single guest, so this often worked. In order to guard against this, bona fide guests had to be issued with ‘key cards’ which showed that they were entitled to a particular key.

Modern hotels use electronic keys made of plastic and punched or magnetically coded with the door code. These generally do not have the room number printed on them, so the guest has to be given an additional key card showing this. He should keep it separate from the electronic room key in case the latter is stolen. The room lock is programmed to accept only the code on the electronic key, which is changed every time the room is let. It can even be changed during the guest's stay should he lose his key. These are relatively cheap, so their loss does not matter very much.

Such electronic keys have cut down the number of thefts from rooms by a significant amount. Just as important from the procedural point of view, they have eliminated the time-wasting process of taking keys in and handing them out again, allowing the receptionists to concentrate on more productive contacts with guests.

In the old days, handling mail addressed to guests was one of front office's more important duties. The older form of key rack was combined with a set of pigeon holes, one for each room, so that the receptionist could hand over any waiting mail whenever she issued or took back the key. Packages too large to go into the rack were dealt with by a simple ‘mail advice slip’.

Figure 28 Room or rate change slip

With shorter stays and increased use of the telephone, such mail has decreased in volume. Many modern hotels (especially those using electronic keys) have discontinued the traditional key/mail rack. Nevertheless, guest mail still arrives, and must be dealt with promptly. The following steps represent ‘good practice’:

1 Guest mail is date- and time-stamped on arrival. This eliminates disputes about delivery times.

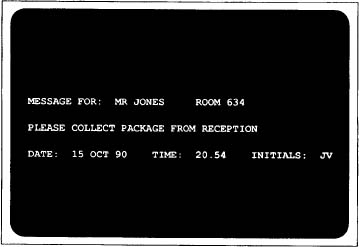

2 It is either placed in the key/mail rack, delivered to the guest's room or held in front office. In the latter case, a message must be sent to the guest. It used to be common to use a standard ‘message slip’ which asked the guest to call at front office to pick up a letter, parcel or whatever. Nowadays he is usually contacted via the telephone. Most bedroom telephones have a ‘message light’ controlled from the switchboard: this flashes until the guest answers it. Computerized systems normally contain a message facility. This allows front office to enter a message either against a room number or guest name. The guest's name and room number are ‘flagged’ so that anyone with access to a terminal can see that there is a message waiting and deliver it if necessary. Messages are logged off when delivered, but remain on the guest file with the fact that they have been delivered noted. These computer-held messages are automatically timed and dated. The text might appear as shown in Figure 29.

3 Messages for guests who are expected but who have not yet arrived are dealt with in much the same way. The advance booking file or arrivals list can be ‘flagged’ in the same way as the current occupancy records, and the message delivered on arrival.

4 Messages for guests who have already left require different treatment. They can be forwarded to the address on the registration card. Security mail (e.g. a registered letter) is best dealt with by sending a notification and request for instructions. The hotel should make a note of any mail forwarded in order to avoid disputes.

Security mail inevitably creates special problems. Once a member of the hotel's staff has signed for such mail, responsibility passes from the Post Office to the hotel. It is therefore very important that only trustworthy employees be authorized to sign, and that the Post Office be informed of their identity.

Incoming telephone calls

Ideally, these should be put straight through to the guest. Switchboard thus needs to know every guest's room number. As we have seen, manual systems had to employ an alphabetical guest index for this purpose. Computer systems allow name searches.

Figure 29 Guest message display

Guests are not always in their rooms. Sometimes they have gone out, but often they are in the restaurant, or bar, or perhaps the pool. Traditionally, they were informed of urgent calls by a process known as ‘paging’. A uniformed employee was sent round the public areas calling ‘Paging Mr Jones... Paging Mr Jones...’ until Mr Jones was finally located. A modern alternative is the loudspeaker public address system. The trouble with both these systems is that they disrupt other guests’ conversations.

More recently, hotels have issued guests with ‘pagers’ on request. This made sense if the guest knew that he was likely to receive an important call out of normal business hours (perhaps because it originated from a country in a different time zone). A note was attached to his bill or file to ensure that the ‘pager’ was recovered before he left.

This kind of problem is becoming obsolete with the advent of the portable telephone.

Outgoing telephone calls

In the past, technical limitations meant that outgoing calls had to be dialled by the hotel's own switchboard operators and then logged by hand. Nowadays, direct dialling and automatic metering systems are almost universal, except in the very smallest hotels.

This has helped to reduce the number of disputes, especially since the time of the call and the number dialled are recorded (in the past, guests sometimes claimed that calls had been made by hotel staff using their pass keys while they themselves were out).

The main area still open to argument lies in the basis on which the calls are charged. Hotels do not have to restrict themselves to just recovering the cost of the call: indeed, since the guest is making use of the hotel's own expensive equipment, an element of ‘mark-up’ is justified. However, this sometimes arouses resentment, and the basis upon which calls are charged should be made clear beforehand.

Safe custody

The Hotel Proprietors Act of 1956 lays down that a hotel proprietor may be liable for any loss or damage to a guest's property even though this was not due to any fault of him or his staff. This liability is limited to £50 in respect of any one article and £100 for any one guest, unless the property in question has been deposited or offered for deposit for safe custody. This only applies if the statutory notice has been displayed, warning the guest of these limitations and effectively advising him to use the safe deposit provision for anything of value.

This provision places the responsibility for looking after such articles directly on the hotel and it also means that it has a duty to accept them for safe keeping. It is no use claiming that you do not have proper facilities or enough staff to look after them. In practice, most hotels install a safe in the front office area, and make this part of the receptionist's responsibilities.

Safe custody routines are simple, but important.

1 When a guest brings an article in for safe keeping, he should be asked to place it in a strong envelope. This prevents different items from becoming mixed up, and also allows him to keep whatever he is depositing private. He seals it and then signs over the seal. The receptionist makes sure that the envelope is marked with the guest's name and room number, and then issues a receipt. The receipt simply specifies ‘one sealed envelope’. The approximate value may be added in order to avoid possible disagreements later.

2 When the guest wishes to reclaim the article, he must produce the receipt. If he has lost or mislaid this, the hotel must satisfy itself that it is really his property, and would be well advised to obtain a signed waiver discharging it from any further liability (it is possible, albeit unlikely, that the guest might later ‘find’ the missing receipt and then demand that the hotel produce the property he had already withdrawn). The receipt should be retained as proof that the item was reclaimed.

This process can seem somewhat irksome, especially if the property consists of jewellery which may be deposited, reclaimed and then redeposited more than once during the guest's stay, but it is the only safe way.

An alternative method is to provide safe deposit boxes. These require the use of two keys, one held by front office, the second issued to the guest against a signature. The guest has to sign a receipt every time he wishes to open his box, which allows the receptionist to compare signatures. The receipt should be countersigned by the receptionist.

Information

One of the receptionist's most important duties is the provision of information about the hotel and the locality. It goes without saying that she ought to know everything about the hotel itself, including details of any special functions which might interest guests.

Many managers assume that because most receptionists live locally they are therefore familiar with all the local features. This is simply not true. Ask yourself, for instance, whether you could direct a guest to the nearest Greek Orthodox Church or antiquarian bookshop. There are bound to be lots of specialist queries of this kind, and all you can do is to know HOW to find the necessary information. You should have all the necessary reference material (the local Yellow Pages, for instance) ready to hand in the front office.

Nevertheless, many queries will be relatively straightforward. Management should be able to anticipate these and train new staff to answer them, even if they don't know the answer from personal experience. This is important as far as the hotel's own ‘image’ is concerned. A busy executive is not likely to form a very high opinion of a hotel whose receptionist can't tell him how long it is likely to take to get by taxi to the local airport.

Some of the facts that guests may want remain unchanged for long periods. These can be dealt with by documents such as maps, guides, brochures or timetables. These can be made part of guest information packs or picked up from the desk. Larger items can be made part of a permanent display in the lobby (this often gives guests something to look at while they are waiting).

Other information may change from day to day, or week to week. This can be brought to guests’ attention through attractive notice boards in the lobby.

Early morning wake-up calls

This used to be an important front office function, but has become much less important with the spread of personal alarms and automated hotel wake-up systems. Nevertheless, you may still receive requests from the older and more nervous type of visitor, and you ought to know how the old procedure worked just in case your electronic system goes ‘down’ sometime.

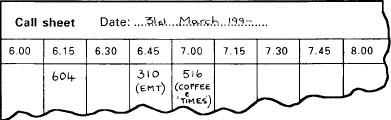

An analysed call sheet was laid out as shown in Figure 30.

The intervals could be five or ten minutes if necessary. As the example shows, the name and room number were written in the appropriate column, together with any special requests. In the morning the receptionist (or switchboard operator) worked from left to right, ticking off each alarm call as it was answered. A similar system can be used for newspaper requests.

Departures

The procedures required on departure are very much a mirror image of those used to record arrivals. The main operation is the presentation and settlement of the bill, which will be dealt with in Chapter 3. However, there are certain other procedures to consider.

One point which is often overlooked is that departure is a good time to do some selling. Another and more obvious one is security. We shall look at both these topics in more detail later. At the moment we will confine ourselves to the procedural aspects.

Confirming departures

In theory, the hotel knows when the guest is going to leave. In practice, this is not always so. Guests sometimes change their plans at the last minute and expect to be able to ‘stay over’ without having given you anything like enough notice. It is good practice, therefore, to confirm departures the night before if at all possible.

Additional services

The guest may require:

![]() an alarm call

an alarm call

![]() a newspaper

a newspaper

![]() assistance with luggage

assistance with luggage

![]() help with onward travel

help with onward travel

These form part of the service ‘package’, and the hotel should try to anticipate any such need rather than waiting to be asked.

Departure notifications

The hotel's other departments need information about departures. The switchboard will want to know which guests will be leaving, the housekeeper what rooms have to be prepared for reletting, and the bar and restaurant may need to be told not to extend any further credit.

This information is often communicated by means of a departure list, which is prepared and circulated in the same way as the arrivals list (indeed, the two can be combined). However, the departure list only shows planned departures, and it was common for large hotels to circulate actual departure notifications as well. These were used to update the departure list. Such hotels now use computerized systems, which handle these notifications automatically.

Updating the immediate records

In a manual system it is vital to keep the room rack up to date. If a card is carelessly left in a slot after the guest has gone, that room will look as if it is not available for reletting. Accordingly, an essential part of the check-out process consists of taking the card or slip out of the rack and disposing of it in some way. Cards normally have the date of departure on them in order to allow them to be checked for ‘stayovers’.

An alphabetical guest index must be updated in the same way. In a manual system this was accomplished by sending a departure notification to the switchboard.

In a computerized system both operations are carried out automatically as part of the check-out entry.

Guest history records

These are intended to provide continuity in the treatment of regular guests. It is often difficult to ensure this because there will be long intervals between visits and the front office staff may have changed in the meantime. Nevertheless, it is very nice to be greeted with something like ‘Hello, Mr Hamilton. Better weather than when you were here last, isn't it? Would you like the same room again...?’, and the guest history card used in some manual systems is designed to allow this to happen. Typically, such cards record:

![]() dates of stays

dates of stays

![]() rooms used

rooms used

![]() total bills

total bills

![]() any special likes or dislikes

any special likes or dislikes

Since such cards have to be made out or updated every time a guest stays at a hotel, they are very expensive in terms of clerical time. Nowadays they are generally only found in the kind of luxury hotel which offers a very high standard of service. Such hotels try to ‘personalize’ their services by keeping records of their guests’ preferences in terms of flowers, food, drinks and even furniture. Most medium-class hotels can no longer afford to keep such records, except possibly for regular guests.

However, the guest history is making a comeback through the agency of computerization. A computerized system can prepare or update guest histories automatically as part of the check-out procedures. As the cost of information storage has come down in real terms, so the availability and usage of guest history modules has increased, and they are now a standard feature of most systems.

One of the main advantages of computerized guest history files is that they can be linked with the advance bookings section, so that the computer ‘searches’ its records to see whether a new booking has ever stayed at the hotel before. It can then ‘prompt’ the reservation clerk via the VDU screen, allowing her to respond appropriately.

Room record cards

These were another optional part of a manual system. They provided particulars of actual occupancies, together with details of any periods during which the room was out of service for repairs or redecoration. They were useful for planned maintenance purposes, but the process of entering the name of every guest who had ever stayed in the room was time-consuming and added little to the information already obtainable from the conventional chart or the registration cards (which, as you will recall, have to be kept for twelve months). Consequently, such cards are now obsolete, though some form of room record is still desirable.

Filing

We need to add a brief word about the filing of the various documents, because these can amount to a considerable stack. There will probably be a reservation form, possibly with an initial letter of enquiry, a confirmation and possibly amendment. There may also be a registration card (unless you are using a book type register) and perhaps a copy of the bill.

Although particulars of the booking are transferred to easily consulted sources like the diary and chart, the primary documents need to be kept within reach in case there is any dispute about the terms. The critical time is likely to be on check-in, though the presentation of the bill on departure may also lead to problems. The documents thus need to be available for reference at these periods.

The logical method of filing advance booking documents is by date of arrival. That way, they can move along as if on a conveyor belt, so that you constantly have today's arrivals to hand. Once the guests are in the hotel, you should rearrange the documents in date of departure order. That way, you will have tomorrow's departures to hand as well.

It is probably most convenient to retain the documents in date of departure order. If there ARE any queries, this is likely to be the date quoted. It also allows you to operate a twelve-month retention period, after which the records are disposed of.

The documents should be arranged in alphabetical order within the date sections. However, there is no need to be too obsessive about maintaining this system in absolutely perfect order. Generally, only a very small number of primary documents ever need to be looked at again, and it is usually enough to know their approximate whereabouts.

Assignments

1 Describe and compare the type of check-in systems you would expect to find in the Tudor and Pancontinental Hotels.

2 How would check-in procedures differ when dealing with: (a) a guest with a reservation; (b) a ‘chance’ guest?

3 Obtain specimens of the type of registration documents and an outline of the check-in procedures used at a selection of local hotels, and compare these with one another, relating their characteristics to the type of hotel involved.

4 What reference sources would you expect a well-equipped front office to possess in order to be able to answer guest enquiries?

5 Discuss various methods of filing guest documentation. To what extent are these systems likely to be affected by developments in computerization?