Chapter 12

Control

Introduction

The importance of the control process cannot be overemphasized. There is no point in having a well-designed, beautifully furnished establishment with highly trained and motivated staff if it fails to reach its objectives.

The control process involves:

1 Establishing targets.

2 Monitoring performance in order to see whether these targets are being attained.

3 Taking corrective action wherever necessary.

The control of front office operations is only one aspect of general management control, which covers all the hotel's operations. In this work we shall be concerned only with front office control, but it must be remembered that this has to be integrated with all the other aspects. Cash control, for instance, is only one part of general financial control, and similar procedures will have to be followed in the bars and restaurants.

The establishment of targets lies outside our terms of reference. Sales targets are usually set by general management, though the expertise of the rooms division manager is clearly an important element in this process, and budgets and staffing levels are commonly decided in consultation with various other heads of department. We shall therefore be concentrating on the way in which front office monitors those activities for which it is directly responsible, namely, the letting of accommodation.

The completion of various kinds of reports is an inescapable part of this process. As we have already seen, they not only tell management what has happened, but they also form the basis for predictions regarding the future. This is particularly important with a business like a hotel, where demand can often vary considerably from one day to the next.

In one respect, the nature of the hotel's ‘product’ makes the control process easier. The inventory is highly perishable, which is just another way of saying that an unsold room night cannot be stockpiled and offered again another day. There are thus no finished stocks or ‘work in progress’ to carry forward, and a twenty-four-hour period can be seen as a natural entity, complete in itself. It is relatively easy to say whether we have done well or badly, and the only factor likely to affect this is the possibility that one or two customers might not pay their bills.

On the other hand, the special nature of the hotel's business makes accounting speed and accuracy particularly important. The hotel must make sure that its bills are correct before the first guests begin to leave in the morning, which can mean six o'clock. The guests themselves often come from far away, and it is difficult to correct errors after they have left. These factors impose special strains on the control process.

There are two essential pieces of information which a front office manager needs to have in order to evaluate the success or failure of the day's operations. These are:

1 The number of rooms let.

2 The amount of revenue earned.

We shall look at each of these in turn. Before doing so, however, we must consider the very important question of verification.

Verification

Control involves records, as we have said, but these are useless unless the information they contain is accurate. Records can be incorrect for two reasons:

1 Staff often make silly, careless errors. They may post a meal voucher to the wrong account, for instance, or simply neglect to post it at all.

2 Occasionally, employees may deliberately falsify records in order to cover up some form of wrongdoing.

Verification is based as far as possible on the comparison of records which have been produced independently. This usually catches any careless, unintentional errors because two people seldom make exactly the same mistake. It also helps to reduce the incidence of deliberate falsification, because there has to be collusion between both parties if it is to succeed.

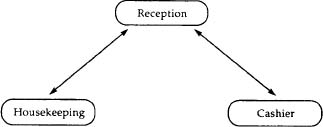

This comparison process has been called ‘the internal audit triangle’. Strictly speaking, it is not a triangle at all because there are really only two ‘sides’, but it certainly has three points. These are the three departments or subdepartments which produce booking and billing records, namely reception, housekeeping and the cashier (Figure 55).

The first side of the so-called triangle is the comparison of reception's record of rooms let with the housekeeper's report. In manual systems, the front office report is based on the room rack. A computerized system will display or print out its own summary of this information, which will be accessible to both departments. This printout will be internally consistent, but it is still necessary to conduct a physical check because it may not reflect the reality of the situation.

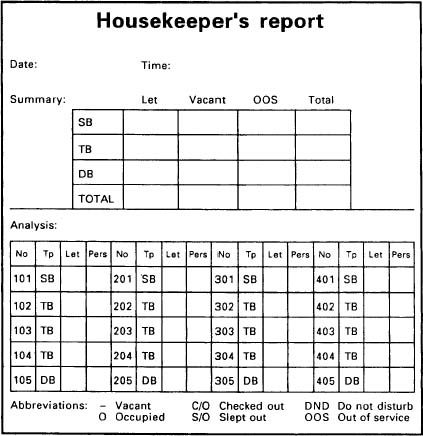

A housekeeper's report is produced independently of front office. It is compiled on a room-by-room basis and summarized by the housekeeper. It looks something like Figure 56, though the layout and abbreviations used will vary from hotel to hotel.

‘Occupied’ means that the room has been used and there is still luggage in it. ‘Checked out’ shows that it was used but the guest has left. ‘Slept out’ means that the room is recorded as having been let but has not been slept in (it may mean that the guest has left the hotel for a day but has asked that his room be kept available, but it may also mean that he had paid in advance and did not bother to call in at the front office when he left). ‘DND’ indicates that the housekeeping staff have not been able to get into the room: if it remains this way for too long, some form of investigation may be called for. ‘OOS’ means that the room is being repaired or redecorated, or is otherwise unavailable.

This report has to be checked against the room rack or computerized room status display. In small hotels there are only likely to be one or two discrepancies, and these can be cleared up quickly. In large hotels it may be necessary to prepare a ‘discrepancies report’, which is sent back to the housekeeper for double-checking.

There will be three main types of discrepancy:

1 The rack shows ‘occupied’ but the housekeeper's report shows ‘vacant’. The possible explanations are:

– The room rack is wrong, usually because the receptionist has forgotten to update it when the guest left. This is serious, for the room might have been let to a ‘chance’ customer. It is quite a common error with manual systems, but much less likely with a computerized one, which will automatically update its room status records whenever a guest is checked out.

– There has been a ‘walk-out’ (i.e. a guest has left without paying). This is even more serious, for it is a definite loss to the hotel, almost certainly including food, drink and services as well.

2 The rack shows ‘vacant’ but the housekeeper's report says ‘occupied’. In this case the possible explanations are:

– Reception has forgotten to update the rack when it registered a guest. Again, this is almost impossible with a well-designed computerized system, especially one that issues a coded room key on registration.

– The room might have been used by staff without notifying front office.

– Someone has deliberately failed to check in a sleeper using the normal procedures. This is the most serious situation of all, for it suggests that the person responsible may be indulging in one of the oldest of all the front office ‘fiddles’, namely, letting a late night ‘chance customer’ into a room on payment of a reduced sum directly to the receptionist (or night porter, since these have often been left in charge of the desk in small hotels). This last possibility is particularly difficult to detect, since there will be no trace of the admission anywhere in the records, and neither the ‘guest’ nor the employee involved are likely to say anything. The crime (for it is a crime under the Theft Act) is easier to commit in a small hotel, where the desk is only manned by one person, but it is not unknown even in large hotels. A computerized system is not necessarily any help since the ‘transaction’ bypasses it completely, and even a key issuing facility does not guarantee protection since the night staff have access to pass keys. As we have seen, modern systems can record every use of a key, but a criminally inclined employee will probably be able to produce an explanation (‘I wasn't sure if it had been cleaned, so I just nipped up to check...’) and in any case such records are not always checked through in detail.

3 There are differences regarding the number of people who have slept in the room. This is another serious matter, especially if the rack says ‘1’ and the housekeeper says ‘2’. One possibility here is that the guest has booked as a single and then smuggled a friend (or a prostitute) in to share his accommodation. This practice is difficult to detect since it will not appear in the records, and also difficult to prove since some single guests in twin rooms do change beds during the night. Nevertheless, the hotel may be losing money, and any unauthorized use must be prevented if possible.

Figure 55 Internal audit triangle

Figure 56 Housekeeper's report

All these possibilities underline the need for the housekeeper's report.

The second side of the internal audit triangle is the checking of the financial records. This has two main aspects:

1 In manual systems it is common practice to check the room rates as shown on the room rack against the bills as shown on the tabular ledger. The object is to ensure that no accommodation charges are missed off. This is usually accomplished by adding up all the room rates as shown on the rack slips and comparing the total with that of the ‘rooms’ column on the tabular ledger. This process does not detect charges which have been posted to the wrong account, but it does provide a check against straightforward omissions. Again, computerized systems are much simpler in this respect because the rate is automatically entered on registration and simultaneously charged to the guest's account.

2 The cash must be checked against the records. There is no point in the latter being accurate if the cash itself is not there. This process is one of the main features of any front office day, because cash is uniquely liquid and will ‘walk’ at the slightest opportunity. Cash control is simple in theory, time-consuming in reality. The main points are:

– All cash received (including foreign currency) must be properly recorded at the time of receipt.

– Manual records should be balanced regularly and reconciled with cash in hand.

– Cash must be kept under lock and key. It is usual for a safe to be provided, but this may also be used for the safe-keeping of guests’ valuables, so separate tills are provided for current ‘floats’ (i.e. cash required for the giving of change).

– Only a limited number of ‘floats’ should be authorized, and these must be signed for and kept under the control of the responsible individual. This implies that the cash should be checked every time the responsible individual goes off shift. This can be a chore, but is a necessary part of the routine.

– Individual cashier codes should be allocated, and these should be kept confidential. Computer systems should make it impossible for any unauthorized person to learn an individual's code.

Night audit

Although each shift is expected to ‘balance up’ before going off duty, hotels normally draw the line under each day's trading between midnight and 6 a.m. the following morning. This is the most convenient time because:

1 There will be few arrivals or transactions during that period.

2 It is essential to check that the accounts are correct before the guests start to leave the following morning.

This process is known as ‘night audit’. In a large hotel it is often the responsibility of a separate employee (or even a small team) known as the ‘night auditor(s)’. The role of the night auditor is as follows:

1 To ensure that any outstanding transactions have been entered. There may very well be some restaurant vouchers to be posted, for instance, or one or two late arrivals, and in a hotel offering twenty-four-hour room service it is always possible that there will be some drinks, snacks or telephone calls to record as well.

2 To verify that all the bills and other accounts are correct. This means checking to make sure that vouchers have been posted to the correct accounts, that cash balances as shown are actually represented by cash in the safe, and that miscellaneous items such as guests’ property deposited for safe keeping are actually there.

3 To verify that front office's guests in residence records are up to date and accurate. As we have seen, this involves using the internal audit triangle.

4 To prepare a management report summarizing the day's trading activities.

Computerized control systems

One of the great advantages of a computerized system is that it reduces the need to duplicate entries, thus eliminating many common types of error. The computer's accounts will always be ‘in balance’, and the tally of rooms let should always agree with the total number of room charges.

This apparent infallibility creates a risk that the control procedures will be reduced or even eliminated. Front office staff using a manual system are always aware of the possibility that a minor error may lead to a discrepancy when they come to ‘balance up’ at the end of their shift. The fact that the computer will always be ‘in balance’ tends to lead to a complacent assumption that those balances are necessarily correct, which is not so. As the well-known computer saying ‘Garbage In, Garbage Out’ reminds us, a computer is only as accurate as its information input allows it to be. If room rates have been entered incorrectly, or charges posted to the wrong accounts, then the final bills will be just as wrong as if they had been done by hand.

It is therefore necessary to check computerized records in the same way as manual ones. There are four steps in this process:

1 The records must still undergo the verification processes we have already described. In particular:

– Room rack printouts should be compared with some form of housekeeper's report. The fact that the computer shows a room as occupied does not necessarily mean that it is.

– All cash balances and items on deposit must be physically checked. Once again, the fact that the computer says they should be there does not necessarily mean that they are.

2 The records also need to go through the night audit process. Systems will vary somewhat in this respect, but are likely to include the following:

– It should be possible to print out a comparison between the rack rates and the actual rates charged for all occupied rooms, with the reasons for any differences. This allows the auditor to check that all discounts and other allowances are properly accounted for.

– It should also be possible to print out a complete record of all transactions posted during the day. This provides the necessary ‘audit trail’.

3 After completion of the night audit process, the computer will probably have to be ‘reset’. This is because its memory is not unlimited, and it is necessary to ‘clear’ it of unnecessary detail before starting to enter the following day's transactions. This process will involve, among other things:

– Setting all daily totals back to zero.

– Updating any cumulative figures.

– Automatically reducing all current stays by one night.

– Deleting all cancellations and departures, and transferring the latter to guest history files.

In the interests of safety, it is essential to make a back-up copy of all the files being deleted, in case there turns out to have been a mistake and it is necessary to go back and re-run. The system in use ought to make all this as easy as possible. As we have said before, many hotels find it advisable to back-up more than once per day. It may also be desirable to obtain a printed record of the items being deleted for future reference.

4 Preparing reports summarizing the day's activities. These are usually much more varied and detailed than is possible with a manual system because of the computer's ability to scan all the data already in the system. With a well-designed program, pressing the appropriate key or keys can produce any or all of the following reports:

– Arrivals List

– Departures List

– VIP Guest List

– Group Tour List

– Chance Guest List

– Regular Guest List

– Cancellations Report

– No Shows Report

– Room Availability

– Vacant Room List

– Rooms Out of Service

– Extra Bed/Cot List

– Room Vacate Times

– Room Changes List

– Maintenance Report

– Messages Report

– Revenue Report

– Deposits Report

– Credit Limit Report

– Commissions Due List

– Corrections Report

– Rate Analysis Report

– Folios (Bills) List

– Currency Report

All of these (and others, too) contain information which can be useful to the front office manager. In addition to these simple lists and summaries, the computer can also produce a variety of management statistics. This task needs to be done within manual systems, too, and is such an important part of front office duties that we ought to consider it separately. Before that, however, we should discuss the various measures of performance which might be used.

Occupancy and revenue reports

The main figures required are simple enough to understand. There are two traditional calculations (occupancy and average rate), each usually subdivided into two (room and guest). In recent years there has been increasing interest in a third (yield, or income occupancy). They are calculated as follows.

Occupancy percentages

These are subdivided into:

1 Room occupancy, i.e.

![]()

2 Bed (i.e. sleeper) occupancy, i.e.

![]()

Both of these are needed in order to check on the incidence of double occupancy. If room occupancy was 95 per cent, for instance, and bed occupancy was only 78 per cent, then you could tell at a glance that a significant number of your twins or doubles had been occupied by single persons. This might not appear to matter very much if the hotel has a ‘per room’ tariff, but don't forget that a single guest can only consume one meal at a time, and that restaurant and bar takings may suffer.

Sometimes management will ask for an additional statistic, namely:

3 Double occupancy, i.e.

![]()

This is self-explanatory.

The main problem likely to arise when calculating occupancy percentages is that of the base figure. The number of rooms available tends to fluctuate for a variety of reasons. Sometimes whole floors or wings are taken out of service during the off season, or individual rooms are closed off for redecoration or staff use. There is a certain amount of disagreement as to how this should be handled. Some hoteliers prefer to base their calculations on the number of rooms actually available, arguing that you can't let a room which has been taken out of service. However, it is best to use a standard base figure throughout. This allows you to see:

![]() The real level of occupancy during the off season (after all, you are still incurring overheads like insurance and depreciation on the empty rooms).

The real level of occupancy during the off season (after all, you are still incurring overheads like insurance and depreciation on the empty rooms).

![]() The proportion of rooms set aside for non-revenue earning purposes, such as complimentaries or staff use (especially if they could have been let).

The proportion of rooms set aside for non-revenue earning purposes, such as complimentaries or staff use (especially if they could have been let).

![]() The proportion of rooms out of service at any time (again, especially if they could have been let. Planned maintenance should ensure that rooms are only redecorated during slow periods: it is important to know if this is not being done).

The proportion of rooms out of service at any time (again, especially if they could have been let. Planned maintenance should ensure that rooms are only redecorated during slow periods: it is important to know if this is not being done).

A second problem may occur should you manage to squeeze in more guests than you appear to have rooms or beds for. This can happen because of ‘day lets’, or because you have put in some ‘Z beds’, or managed to convert a spare room of some kind, as occasionally happens during periods of very high demand. A few hoteliers argue that you ought to increase the base figure in these circumstances, because you can't really have an occupancy of more than 100 per cent. However, this is an accepted convention within the industry, and everyone knows what it means.

Average rate figures

These are subdivided into:

1 Average room rate, i.e.

![]()

2 Average guest rate, i.e.

![]()

Again, it is useful to have both figures in order to provide another check on the incidence of single letting of twin or double rooms. If a hotel had 100 standard twin rooms, each occupied by only one sleeper at a per person rate of £40, the figures would be as follows:

1 Average room rate:

![]()

2 Average guest rate:

![]()

The difference between the two rates makes it clear that there has been a significant amount of single letting.

The main value of these average rate figures is that they give us a quick indication of the extent to which discounting is taking place. It would be easy to achieve 100 per cent occupancies night after night by reducing the room rate to £1 per night, but this wouldn't be very profitable.

It is possible to compare these average rates with a breakeven figure and thus tell whether the rooms division has made a profit or a loss on any particular night.

Yield

A major disadvantage of the average rate figures is the difficulty of comparing one year's figures with another, especially after periods of high inflation. Suppose your hotel's current average guest rate is £74.50, whereas in 1970 it was £9.75. Is it doing better or worse? What you need is a handy yardstick for this kind of comparison.

This has led to increasing interest in yield (sometimes called the ‘income occupancy percentage’). As we saw when we looked at yield management, it is calculated as follows:

![]()

The optimum room revenue is, of course, the maximum obtainable given 100 per cent occupancy at full rack rates.

Yield allows us to compare performance over a period of years. Returning to our hypothetical example, let us assume that our 100-room hotel had an optimum room rate of £10 in 1970 and £80 today. Its average occupancies were 90 per cent in each case. The yield calculations are as follows:

1970

![]()

Today

![]()

Now it is easy to see that our hotel was doing better in 1970.

Yield assesses both our ability to fill the hotel and our ability to obtain something close to the full rates for the rooms. A high but heavily discounted occupancy pattern would produce a relatively low yield, as would a low occupancy pattern at the full rack rate.

Yield is thus the single most important measure available to management, though it needs to be supplemented by occupancy and average revenue figures to explain just why it may have gone up or down. In turn, these can be further split according to room types to give even greater control. The process might be illustrated diagrammatically as shown in Figure 57.

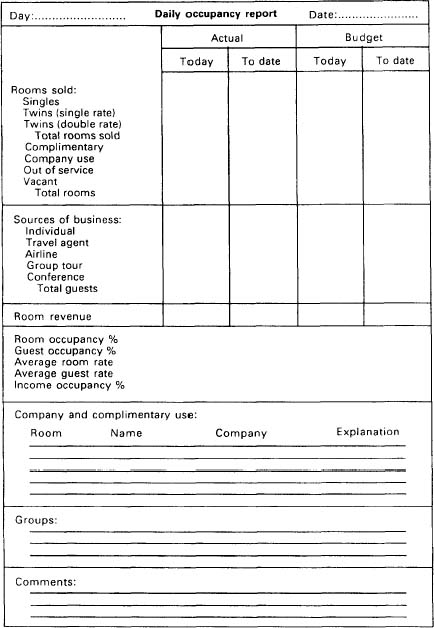

Daily occupancy reports

The various figures we have been discussing need to be combined in a regular daily report. Five desirable features of such reports should be noted:

Figure 57 Control pyramid diagram

1 The figures should be comparative. In other words, they ought to compare what did happen with what you thought should have happened, thus allowing you to assess the accuracy of your predictions. You should be familiar with the concepts and practices of budgetary control, and be able to see how these apply here.

2 Space should be allocated to an ‘analysis of business’. We pointed out when discussing yield management that different types of customer may very well be paying different rates. The overall results of the actual sales mix achieved will be revealed by the average room and guest rates, but it is useful to be able to explore this further. The categories will not be the same for all hotels, of course, but most are now taking much more interest in the kind of business they are attracting.

3 Space should also be set aside for a detailed analysis of house use and complimentaries. This is necessary because otherwise a devious employee might put a friend in a room under one of these headings. Comparison of the room rack with the housekeeper's report would reveal no discrepancy, and the housekeeper's department would not usually query the allocation. It is thus necessary to scrutinize any such use carefully.

4 It is useful to note any groups or conferences being hosted. These can have a significant effect on total occupancies, and should be recorded for future reference.

5 Finally, space should be set aside for ‘comments’. This is not (as you might suppose) to allow you to note any unusual incidents, but rather to record anything else which is likely to have affected the occupancy level, such as ‘heavy fog’, ‘rail strike’ or ‘major exhibition’. These are all events which will make the occupancy percentages non-typical, and it is important to record them for future reference.

A possible layout for such a report is shown in Figure 58. There will be many variations in practice.

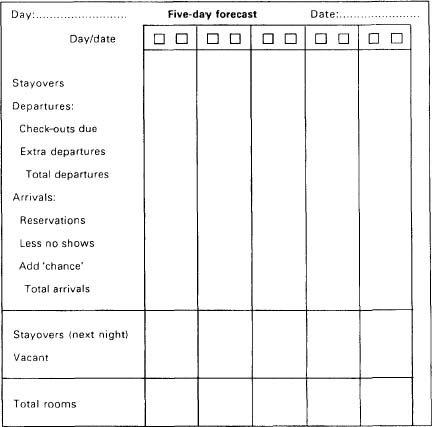

Forecasts

Control is not just a historical process. In fact, there is no point in calculating any of the figures we have been discussing unless they are used to improve future performance.

An important part of this process is forecasting. We have already looked at this in connection with yield management. However, there is also a need for relatively detailed short-term forecasts in order to help reservations staff to make last minute booking decisions, and also to assist other departments in their planning.

Figure 58 Daily occupancy report

The short-term forecast period is usually five to ten days. The forecast is prepared daily, so that each day is recalculated up to ten times with ever-increasing accuracy. A possible layout for a five-day forecast is shown in Figure 59.

This assumes standard rooms and ignores possible single occupancies of twins. It could be made more detailed if required. However, it does indicate the kind of factor which needs to be allowed for when preparing such forecasts, namely:

1 The number of extra or unplanned departures likely.

2 The likely ‘no-show’ rate.

3 The likely number of ‘chance’ guests.

Figure 59 Five-day occupancy forecast

All these can be forecast with considerable accuracy on the basis of experience. Obviously, your predictions will not be exactly correct, but the stayovers figure can be updated daily on the basis of the actual arrivals.

Other statistics

There are a number of other control statistics which management will find useful. They include the following.

Average daily spend per guest

This is particularly helpful if it is broken down by guest category, because then it reveals which market segments are worth attracting on the basis of their total spending within the hotel and its various facilities. Casino hotels, for instance, are well aware of differences in the amounts wagered by the single booking ‘high roller’ on the one hand and the ‘package tourist’ on the other.

The figure is easily calculated:

![]()

Average stay per guest

This is also useful in terms of deciding which type of guest to attract, but more so in determining the kind of facilities which need to be offered. In general, the longer the stay, the more varied the meal and other ‘experiences’ required. A careful watch on the length of stay figures will enable management to make sure that they continue to make proper provision for these needs.

The figure can be obtained relatively easily by taking an appropriate period, such as a week or a month, and then calculating it as follows:

![]()

An alternative approach is to take the ‘nights stay’ figure from the registration forms, add them up, and then divide by the total number of forms. This figure will not be precisely accurate because of overstays and early departures, but experience suggests that these tend to cancel each other out and that the final figure is accurate enough for most purposes.

Analysis of guests by nationality

It is useful to be able to see where guests come from in order to be able to discern trends and assess the effectiveness of particular marketing campaigns.

This figure is easily obtained by analysing the registration forms and then turning the figure for each country into a percentage. For instance, if a hotel had 1,340 visitors during the period under consideration, of whom 265 were from the USA, the percentage of American visitors would have been 19.78 per cent.

Analysis of business by region of origin

This is very similar to a nationality analysis, and may in fact form a continuation of that process. It is often helpful to know from which regions one's guests are coming from.

This information is obtained by analysing the addresses given on the registration forms. A highly detailed breakdown is not usually necessary: it is usually sufficient to use standard regions such as ‘South East’ or ‘North West’.

Analysis of bookings by source of business

This is another useful statistic. It allows us to measure the effectiveness of different bookings channels, and also offers some guidance as to yield.

This figure can also be obtained by analysing the reservation forms, providing these note the source of the booking. It is simple to add the bookings from different sources together and then turn these into percentages as you did with the guests’ nationalities.

Lost room revenue

This is the number of rooms unsold multiplied by the average rate achieved (in practice, since most hotels fill up ‘from the bottom’, this will understate the amount of the loss slightly). It represents what we might have done given better marketing and sales techniques. There is a school of thought which argues that this is the most important statistic of all, because it creates a sense of urgency. A 90 per cent occupancy rate can lead to a degree of complacency, whereas reporting that ‘We didn't sell 10 per cent of our rooms last night’ makes one want to do better.

Denials (business turned away)

It is very useful to know how many requests for accommodation are being turned away. In practice, late cancellations and no shows mean that a high level of requests can still result in an occupancy percentage of less than 100 per cent.

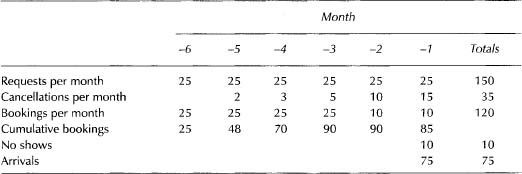

Table 17 shows how this can happen. It shows the booking position in respect of 100 standard rooms over a six-month period up to the date of arrival.

Table 17 Lost occupancy from cancellations

In this example, requests remain steady at twenty-five per month, while the number of cancellations increases steadily (we have assumed that these come in after the requests, which is not entirely true but helps to simplify the calculations). The other figures are obtained as follows:

1 The first requests are received during month -6 (i.e. six months before arrival), and all can be accommodated. The cumulative bookings figure (i.e. total bookings taken) is thus 25.

2 During month -5 the hotel accepts another twenty-five requests, making fifty bookings in all, but it also has two cancellations, so the cumulative bookings total is reduced to 48 (25 + 25 - 2 = 48).

3 During month -4 the hotel accepts another twenty-five requests, but since it also receives three more cancellations the cumulative bookings total is only 70 (48 + 25 - 3 = 70).

4 During month -3 it accepts twenty-five more bookings and has five more cancellations, yielding a cumulative bookings total of 90 (70 + 25 - 5 = 90).

5 During month -2 it receives another twenty-five requests. However, it can only accept ten of these since it already has ninety bookings and there are only 100 rooms. It also receives ten cancellations, so the cumulative bookings total remains at 90 (90 + 10- 10 = 90).

6 During month -1 (the last month) it receives a further twenty-five requests, of which it is able to accept ten. However, it also receives fifteen cancellations, so that the final figure for expected arrivals is only 85 (90 + 10 - 15 = 85). Of these, ten turn out to be no shows, so that the eventual arrivals total is only 75!

Overall, the hotel received 150 requests, of which only 120 were taken, leaving thirty denied. Deducting the cancellations and no shows, true demand was 105 per cent rather than the 75 per cent occupancy actually realized (seventy-five completed bookings plus the thirty denied), though this does not allow for denials who might have cancelled later or turned out to be no shows.

In practice, few hotels record denials because they involve making a separate entry, often when the front office staff are very busy. However, we have already suggested that a wait list is a good idea. If brief details of any unmet requests can be entered on this (name, contact number, room type and dates required), then the production of denial statistics becomes much easier. Any name not crossed off the wait list (i.e. not eventually roomed) will be a denial, and these can be added up. Usually this will only involve a limited number of nights, so the administrative burden is not as excessive as it might at first appear.

We have already indicated that overbooking can help to reduce the impact of late cancellations and no shows. However, it is still useful to know just how much demand there really is. It may justify management in adding some extra rooms!

It should be obvious that you will obtain the greatest benefit from putting all these different statistics together. You may, for instance, find that certain nationalities stay longer and occupy higher priced rooms than others, or that group business produces a lower average spend overall. Many of these results are likely to be self-evident, but you may well get one or two surprises.

Assessing guest satisfaction

Since the guest is the focus of all the hotel's services, it is important to try to find out how successfully his needs are being satisfied. Upward or downward trends in the occupancy percentages will indicate this in an indirect way, but these might be influenced by all kinds of other factors, from changes in the economic environment to the arrival of new competition in the vicinity.

One way in which managers have tried to do this has been to get people to stay at the hotel as guests and then report back on their experiences. However, there is really no substitute for the real guest's own comments. Unsolicited letters are perhaps the most genuine type of feedback you can have: only a small minority of visitors take the trouble to sit down and write a letter afterwards, and it is a good rule of thumb to assume that one letter represents around ten or so satisfied (or dissatisfied) customers. In other words, they should be taken seriously.

‘Prompted’ comments can also be useful. If you are serious about wanting to find out whether your package is really satisfying the guest, the quickest and simplest method of finding out is to ask him directly. However, such replies need to be kept confidential. Old-fashioned hotels often used to maintain a visitor's book in which guests were invited to write their comments. In theory these could be critical: in practice they hardly ever were, mainly because the writers knew that their comments could be read by everyone else who stayed at the hotel.

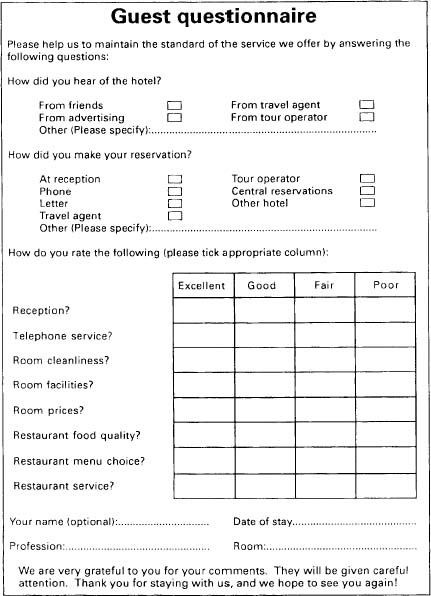

Guests’ views are best obtained by means of a ‘guest questionnaire’. This is usually left in the guest's room. Not all guests actually complete it, but those who do can provide useful data. Such questionnaires should:

![]() Be as short and easy to complete as possible (this means using boxes for ticks rather than asking for extended comments).

Be as short and easy to complete as possible (this means using boxes for ticks rather than asking for extended comments).

Figure 60 Guest satisfaction questionnaire

![]() Commit the guest to expressing a positive opinion rather than just ‘ticking the centre column’.

Commit the guest to expressing a positive opinion rather than just ‘ticking the centre column’.

![]() Allow guests to remain anonymous if they so desire.

Allow guests to remain anonymous if they so desire.

![]() Contain an explicit promise that the guest's opinions will be studied and, if necessary, acted upon.

Contain an explicit promise that the guest's opinions will be studied and, if necessary, acted upon.

![]() Thank the guest (in advance) for any information provided. This is only normal courtesy, but it is particularly important within the context of an establishment dedicated to ‘service’.

Thank the guest (in advance) for any information provided. This is only normal courtesy, but it is particularly important within the context of an establishment dedicated to ‘service’.

Normally such a questionnaire will cover the whole of the hotel ‘package’ rather than just its accommodation aspects. It may look something like Figure 60.

Assignments

1 Compare the control systems likely to be found in the Tudor and Pancontinental Hotels.

2 Obtain specimens of the type of control vouchers and other documents used at a selection of local hotels, and compare these with one another, relating the characteristics to the types of hotel involved.

3 You are acting as front office manager in a large hotel. At 11.00 a.m. you discover that there is a discrepancy between the room rack and the housekeeper's report regarding occupancies for the preceding night. According to the latter, Rooms 802 (single) and 1125 (twin) have been occupied, whereas the room rack does not show this, and no bills have been made out. What steps would you take?

4 Describe how the front office control system relates to the management control system of a hotel as a whole.

5 The table below shows a room rack at the start of the evening.

The following amendments were recorded during the remainder of the evening:

![]() Mrs Carter negotiated a change to Room 107 @ £24.

Mrs Carter negotiated a change to Room 107 @ £24.

![]() Mr/s Nolan arrived and were allocated Room 204 @ £40.

Mr/s Nolan arrived and were allocated Room 204 @ £40.

![]() Mr Clark arrived and was allocated Room 201 @ £24.

Mr Clark arrived and was allocated Room 201 @ £24.

![]() Miss Drury arrived and was allocated Room 207 @ £24.

Miss Drury arrived and was allocated Room 207 @ £24.

![]() Mr/s Creery and their two daughters arrived and were allocated Rooms 105 and 106 @ £40 and £30 respectively.

Mr/s Creery and their two daughters arrived and were allocated Rooms 105 and 106 @ £40 and £30 respectively.

Design a simple room occupancy and revenue report to record letting performance and complete it for the night in question.