Chapter 8

Marketing aspects

Introduction

We have seen that front office can do more than is sometimes thought in terms of raising room revenue. However, attracting new customers is properly the concern of the sales and marketing department. Much of its work lies outside the scope of this book, partly because it concerns the hotel as a whole (including its banqueting and other facilities), and partly because marketing itself is a much broader concept than ‘selling’.

According to the British Institute of Marketing, it is ‘the management process responsible for identifying, anticipating and satisfying customer requirements profitably’. This covers many activities which do not form part of the day-to-day work of front office, such as consumer orientation, market research, product analysis and promotion. Hotel marketing as a whole is thus too big a subject to compress into one chapter, and we recommend that you read one of the many excellent texts on this subject.

Nevertheless, front office staff ought to be aware of the importance of having what is called a ‘marketing orientation’. As we have already pointed out, room revenue is vital to a hotel. Reservations clerks must rid themselves of the old-fashioned attitude that they are only there to handle bookings, and that how the would-be guest comes to hear of the hotel in the first place, or what he thinks of it as a result of his stay is none of their business.

Reaching the customer: advertising

Most commercial organizations fall into one of two classes:

1 Their market is local, and thus easily reached through media such as local newspapers, TV, cinema advertisements and the like. Most restaurants fall into this category.

2 Their market is dispersed, but linked together by a common enthusiasm so that it can be reached via ‘special interest’ journals. There are any number of these magazines available, catering for interests as diverse as boat-owning, computing, dog breeding and walking.

Hotels do not fall into either category. Although there are always some guests who live nearby (they may be moving house, for instance, or reluctant to drive home after a celebration) and a certain number of bookings result from local recommendations (neighbouring firms will often arrange accommodation for visitors with nearby hotels), the greater part of a hotel's business comes from people who live some distance away and who have few ties with the locality (if they had, they might well be invited to stay in private houses). Moreover, in most cases visitors come from a variety of regions and even countries. This makes localized advertising difficult.

Nor is the hotel's market a specialized one. Businesspeople are seldom confined to only one sector of industry, and there are also travelling professionals, tourists and people visiting friends or relatives. These guests have little in common except a need to stay in a particular locality for one or more nights. In other words, the market is very heterogeneous, and this makes it difficult to reach via any of the ‘special interest’ channels we have mentioned.

Reaching the customer: relationship marketing

The difficulties hotels have in reaching new customers make it all the more important for them to retain the loyalty of their existing ones. Hotels have always tried to do this, but the development of the ‘branding’ concept in industry as a whole, coupled with the creation of computerized marketing databases, has led to modern groups tackling the issue in a much more systematic manner. This new approach is called ‘relationship marketing’.

Relationship marketing aims to build business by:

![]() Maintaining existing customer loyalty.

Maintaining existing customer loyalty.

![]() Creating brand awareness among new customers.

Creating brand awareness among new customers.

It does this by advertising various concessions to frequent-stay customers. These can include:

![]() Privileged check-in facilities.

Privileged check-in facilities.

![]() Free or concessionary rates for partners.

Free or concessionary rates for partners.

![]() Room upgrades.

Room upgrades.

![]() Late check-out privileges.

Late check-out privileges.

![]() Free nights after a certain number of stays.

Free nights after a certain number of stays.

This approach may seem to be aimed primarily at the existing customer. However, relationship marketing aims to attract customers from other hotel groups, too. It uses sophisticated market research techniques to identify these, then highly personalized methods such as mail shots or telephone calls to approach them.

Obviously, this is only economic if the individuals concerned generate a lot of room revenue (i.e. they are frequent travellers and normally stay in expensive accommodation).

Reaching the customer: intermediate agencies

The problems hotels experience in reaching new customers lead them to use third parties as intermediaries. This costs money in the form of commissions, of course, but then so does advertising.

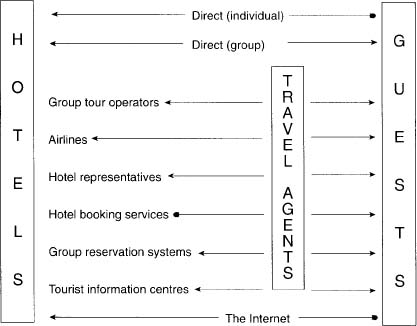

Let us consider the various means by which hotels and their customers can be brought together (Figure 43).

A point to consider in connection with Figure 43 is whether the intermediary is an ‘agent’ in law or a principal. If a travel agent books accommodation with you on behalf of a customer, your contract is with the customer, not with the agency, and since an agent cannot be liable for the actions of his principal, you cannot claim damages from him if the customer does not turn up. On the other hand, a tour operator normally books accommodation on their own account, in which case you can sue if he defaults.

Direct individual sales

This is the simplest method. The would-be guest chooses a hotel and then contacts it by letter, telephone or some other medium. The only parties involved are the hotel and the customer.

Of course, the customer has to find out about the hotel first. This involves some kind of advertising or promotion. Typical methods include mentions in guidebooks, local accommodation brochures or directories such as the motoring organization handbooks. Since one of the themes we shall be emphasizing in this section is that hotels have to pay to reach their customers, we should point out that such ‘mentions’ are seldom free. There is almost always a charge of some kind, even if it comes in the form of a subscription to whatever local agency might be promoting and distributing the brochure.

One of the main problems with direct contact is that the customer is usually located a considerable distance from the hotel. This means that he has to place a long distance telephone call in order to make a booking, and might have to repeat this several times in order to obtain a room at a particularly busy period. This costs money and (what is often worse) often takes a good deal of time. Most of the intermediaries shown in Figure 43 exist in order to save the customer this kind of trouble.

However, not all travellers bother or are able to arrange accommodation in advance, and a hotel can always appeal directly to these. Roadside advertisements are examples of this approach, especially when combined with displays saying ‘Vacancies’ or ‘No Vacancies’. Motels often make use of these, for obvious reasons. Advertisements in or near local stations and airports can serve much the same purpose. Some overseas airports have a row of courtesy phones: leased by local hotels, they put the newly arrived passenger through to the hotel's front desk. Some hotels have actually located duplicate front desks at their local airport. All these are examples of the hotel trying to lessen the ‘distance’ between the would-be guest and its sales desk.

Nowadays the Internet offers an updated mechanism allowing would-be guests to contact hotels directly. However, this medium is so important that we will deal with it separately.

Direct group sales

Many ‘direct’ bookings are actually made on behalf of groups of one sort or another. Some of these are relatively small, such as sports clubs outings, overnight functions and the like, but others can be very large, such as major conferences. These are sometimes arranged by specialist agencies, but quite often the organizer prefers to deal with the hotel directly.

Groups are so important as a source of business that they are an exception to the usual rule that it is not worth the hotel's while to try to contact the customer directly for some face-to-face selling.

As members of the group doing the booking, conference organizers are not usually entitled to any kind of commission. However, they are influential, and they do relieve the hotel of a certain number of administrative chores, so that some kind of incentive is both called for and justifiable. The size of the group itself can be reflected in the price reduction offered to members, while the conference organizer can be rewarded (or compensated) by a complimentary room.

Travel agents

There are two main types:

1 Retail agents. These are the common and familiar high street agents who sell direct to the public. Their main business is to arrange holidays for their customers, including hotel accommodation.

2 Company agents. Some city centre agencies specialize in business house travel, while organizations such as major multinational companies are so big that it is worth their while to have their own travel agency to handle all their business. Sometimes they buy one outright, sometimes they simply invite a small agency to specialize in their business. Either way, the agency is likely to handle a lot of valuable bookings. It receives the usual commission, though some of its profits are likely to be passed on to its parent company or major client.

Travel agents make their money from commissions received on the sale of tickets and bookings. Since tickets are fixed in price, the mechanism is simple. The agency carries a stock of blank tickets and simply remits the money less the commission to the carrier after it sells one. Hotel accommodation is more awkward because the final bill may include ‘extras’ like drinks and laundry. This has led to differences of approach:

1 In some cases, the agency leaves the customer to pay the bill and then invoices the hotel for its commission. This is advantageous for the hotel but less so for the agency, since payment can be delayed. Moreover, the amounts are often relatively small and are sometimes exceeded by the clearing charges.

2 In other cases, the travel agent gets the customer to pay a deposit, which it then forwards to the hotel after deducting its commission. This is less satisfactory for the hotel since smaller agencies can have cash flow problems and sometimes the customer arrives before the deposit does. Credit facilities should only be extended to travel agents if they have been approved by the appropriate regulatory association.

3 Yet again, the agency may charge the customer the whole of the accommodation cost in advance and issue him with a voucher in exchange. He presents this to the hotel, which credits him with the amount. The hotel then presents the voucher to the travel agent concerned and receives payment less commission in return. Agency vouchers are very convenient for the agencies (which get their payment in advance) and for the customers, but hotels need to treat them with some care since there is no standardization. Some agencies issue impressive looking ‘passports’ which actually do not commit them to paying anything at all.

Group tour operators

These include the familiar names whose brochures you will find in any retail travel agent. Many of the larger ones have their own retail outlets. In all, they sell an enormous number of holiday ‘packages’ and book a comparable amount of space at hotels.

This category also includes a vast number of smaller operators of various sorts. Some undertake ‘speciality’ work, arranging battlefield or birdwatching tours, safaris, ski trips and the like. Others specialize in arranging conferences. One of the fastest growing sectors is that of incentive travel, usually arranged by a company for its clients or its successful sales staff. This is a specialized field, and it has attracted its own full-time companies which provide a range of consultancy and administrative services.

Group tour operators do not receive commission because they are not introducing clients but rather booking the space themselves. They make their money from the difference between the cost of the separate elements of the ‘package’ (transport, food, accommodation, entertainment, etc.) and the price they are able to charge for it as a whole. Clearly, the more cheaply such an operator can obtain hotel accommodation the better from his point of view, so negotiations with them are keen, especially since the volume of business they control gives them enormous leverage.

Foreign tour operators often delegate local arrangements to specialist companies called ‘ground handlers’, who make transportation, tour and other arrangements on behalf of their principals. This means that while your basic contract is with the tour operator, detailed arrangements may be in the hands of someone else. Since the ground handler is usually local, this is helpful rather than otherwise.

Airlines

The major airlines are in a special position, since they are large and commercially very powerful.

They are important to hotels because:

![]() The nature of their operations means that they are constantly having to send their flight crews to ‘overnight’ in hotels all over the world, and this in itself means that they create a considerable amount of business.

The nature of their operations means that they are constantly having to send their flight crews to ‘overnight’ in hotels all over the world, and this in itself means that they create a considerable amount of business.

![]() They deal with an enormous number of travellers. Such travellers often find it convenient to arrange other services, such as car hire and hotel accommodation, at their destinations as part of the booking process. This puts the airlines in much the same position as the nineteenth-century railway companies, who also used to make hotel bookings for their passengers, and who even found it profitable to own and operate their own hotels.

They deal with an enormous number of travellers. Such travellers often find it convenient to arrange other services, such as car hire and hotel accommodation, at their destinations as part of the booking process. This puts the airlines in much the same position as the nineteenth-century railway companies, who also used to make hotel bookings for their passengers, and who even found it profitable to own and operate their own hotels.

![]() They frequently have to make arrangements for travellers ‘grounded’ through no fault of their own. Arranging overnight accommodation for a planeload of passengers held up by fog or some other operational problem is a common task for airline staff, and can be a useful source of business for hotels in the vicinity of major airports.

They frequently have to make arrangements for travellers ‘grounded’ through no fault of their own. Arranging overnight accommodation for a planeload of passengers held up by fog or some other operational problem is a common task for airline staff, and can be a useful source of business for hotels in the vicinity of major airports.

All this means that airlines are often able to insist on ‘free sale’ arrangements, whereby you allocate a block of rooms for them to sell, but they incur no penalty if they remain unsold.

One of the important points to note about the airlines is that they have developed highly sophisticated worldwide bookings systems, which are increasingly being linked with those of other service providers, such as car rental firms and hotel group reservation systems, to create what are called ‘intersell agencies’. This means that travel agents can book complete travel packages with one call and on a ‘real-time’ basis. The development of such ‘global distribution systems’ has been rapid and can be expected to continue. They are likely to have a profound effect on the way in which bookings are carried out.

Hotel representatives

Hotel representatives were originally an American idea, developed because the USA is a large country with widely dispersed centres of population, yet a lot of business travel. Hotel representatives base themselves in one such area (some now have worldwide representation) and act as sales and reservation agents on behalf of a number of non-competing hotels from other regions. Local travel agents are able to make bookings for their clients quickly and cheaply, rather than incurring the expense involved in long distance telephone calls. Representatives will also distribute your brochures and other promotional material locally. They are usually paid an annual fee plus commission on the reservations they generate.

Hotel booking agencies

Some areas are short of hotel space and it is particularly difficult to find accommodation in them at busy times of the year. This is fine for the local hotels, but not much fun for those trying to make bookings there. This has led to the development of specialized hotel booking agencies.

Some of these offer this service to individuals. You can often find their outlets in important travel centres such as major railway stations. They are a particularly useful source for ‘last minute’ bookings. As with most intermediaries, they make their money by charging commission on the bookings they arrange. This is frequently levied in a quick, simple and foolproof way. The client pays the agency a booking fee (typically about 12.5 per cent of the first night's accommodation charge) and receives a receipt. He then presents this to the hotel and has an equivalent amount deducted from his bill. In effect, the hotel has paid the agency.

Other hotel reservation agencies deal mainly with travel agents or conference organizers and offer a national, continental or even worldwide service. Such agencies earn their living from commissions in the usual way, though there is usually also a ‘systems’ charge to cover the installation of any specialized equipment.

Group reservation systems

These are designed to help customers to book accommodation at any of the hotels within a group, usually with one local telephone call. They offer a valuable service to travel agents, who may have to make a number of bookings at different locations at the same time. However, the facilities can also be useful to the individual traveller, who is able to make a booking at a distant hotel with one local call. An incidental advantage is that the systems make it easier for the group to monitor overall booking trends.

Although we have used the term ‘group’ reservation systems, independent hotels can benefit from the same service by joining what is known as a reservations consortium. At its simplest, this means that each participating hotel undertakes to recommend its partners, which it guarantees will be of equivalent standard. A rather more elaborate version of this system actually sets up a central reservations system which operates on the same lines as those run by the larger chains.

Group reservation systems began in the USA, where there has always been a good deal of long distance business travel. British groups developed their own systems during the later 1960s, and there was even an attempt to create a national system in 1969. However, many of the larger groups refused to join this because they feared that the business it brought them would be ‘substitutional, not additional’ (in other words, people who would normally have booked with them directly would now go through the new system). This doomed the scheme, which operated at a loss for three years and was wound up in 1972.

This story illustrates the basic problem with the earlier schemes, namely, that they were expensive to operate. They required a central reservations office in addition to the hotels’ own back offices, and that cost money. Typically, a customer would ring the central office to make a booking. The central office would then have to notify the hotel as quickly as possible. This meant that each booking had to be handled twice, once by the central office and once by the hotel. Moreover, the communication costs were transferred from the customer (who only made a local call) to the hotel group.

It is difficult to be precise about the actual level of costs. One major group made its central reservations office a separate subsidiary, which then charged the group hotels 15 per cent of the accommodation cost for all bookings made through it. Others did not reveal their central reservation unit's costs, but there are indications that these were usually around 10-12 per cent of the value of the bookings handled. Even if they did not create separate subsidiaries, good accounting practice led such companies to charge their participating units in proportion to the amount of use they made of the service.

Consequently, individual hotels tended to use central reservations agencies when they needed to boost their occupancies, but opted out when they thought they could fill up without their help. This was, of course, precisely when the customers needed the service most!

As a result, the groups handled only about 10 per cent of their bookings through their central reservations systems. They were mainly used by travel agents, and there were indications that the systems were not actively promoted once usage had reached a certain level.

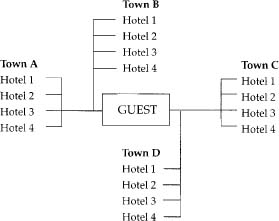

This situation began to change following the introduction of computers. At first these were large central mainframe machines, which were probably just as expensive as the central reservations offices. Nowadays, however, smaller computers located in individual hotels can communicate directly with one another, eliminating the need for a separate central office or facility and thus reducing the cost significantly. The two alternative approaches can be shown diagrammatically as in Figure 44.

Under the new system, the guest can call the group hotel nearest to his home (Hotel ‘C’ in this case) and make a booking at any hotel with the group. The various hotel computers are linked by leased cables, and the clerk can call up either her own booking chart OR the charts for Hotels ‘A’, ‘B’, etc., and make a booking directly into one of the latter.

The costs are very much reduced because the bookings are now only handled once. In theory, there should be little or no extra work for the reservations staff (those in ‘outlying’ hotels might find themselves handling more enquiries for popular ones in central locations, but the overall effect will be to distribute the national workload more evenly). The cost of the necessary equipment can be discounted because the computers themselves would have been introduced in any case and the cost of the extra programming required to support the interchange of information is relatively insignificant. The only remaining cost penalty is that of communication (the customer is only making a local call and the charge for transmitting the details from Hotel ‘C’ to Hotel ‘A’ falls on the group), but this is acceptable because the service to the customer is greatly improved. Not surprisingly, groups which have introduced this type of system claim that usage has increased dramatically (a rise from 10 per cent to something like 50 per cent has been mentioned).

Figure 44 Group reservation system

Tourist Information Centres

The idea behind the Tourist Information Centre is quite different to that of the group reservation system. The latter aims to help customers to book at group hotels anywhere in the world. A Tourist Information Centre aims (among other things) to help customers to book accommodation at any hotel within its own local area. It resembles the hotel booking service, except that it is not a commercial enterprise but a local government service.

The Tourist Information Centre also differs from most of the other intermediaries in terms of the type of customer it deals with. Group reservation systems tend to be set up by the big international hotel chains and used by agencies specializing in business travel services. Tourist Information Centre booking services tend to be used by private individuals interested in much cheaper accommodation, often of the bed and breakfast type.

Information services for tourists are very much a European institution. Holland introduced them as long ago as the 1890s, and now has close to 500 ‘VWs’ (the Dutch term) at village, district and provincial level, all co-ordinated by a national advisory body which has standardized reservation procedures. Most other European countries have similar systems. Some are operated by local authorities, some by regional governments.

The basis for their financing differs in detail, but typically some 60 per cent of their funds comes from the local or regional government, 20 per cent from registration fees paid by listed hotels and other establishments (restaurants, camp and caravan sites and the like), and 20 per cent from profits on the services provided for tourists (the sale of maps, guides, profits on sightseeing tours, etc.).

The Tourist Information Centres’ main role is to provide information about local tourist facilities, including shops and restaurants, historic buildings and other sights, festivals and other celebrations. They also provide details of local hotels and boarding houses, and the great majority will undertake to book accommodation. Although this is only one of their activities, it is the one which concerns us here.

In principle, every establishment within the municipality is registered with the Tourist Information Centre and classified according to location, type, facilities and price (most European countries have compulsory registration, classification and grading of hotels, and frequently a degree of price control as well). A clerk can then ask ‘Which part of town do you want to stay in, and how much do you want to pay?’, select an appropriate hotel on the basis of the responses, ring it up and make a booking on behalf of the tourist.

This has sometimes seemed to present a problem to those unfamiliar with the system. They argue that employees in state- or subscriber-based systems cannot be impartial in recommending individual hotels. However, European agencies have been doing so for nearly a century now, and there have been very few accusations of bias.

In 1988 it became compulsory for all British Tourist Information Centres to offer an accommodation booking service. The systems used have varied considerably in terms of elaboration because of the differing sizes and resources of the Tourist Information Centres. The most sophisticated was probably the Budget Accommodation Service operated by the London Tourist Board: this dealt with hundreds of clients daily over the summer high season and used a ‘queuing’ system whereby the customer was given a number and asked to wait while the staff rang round until they found him accommodation.

Tourist Information Centres have often tended to be somewhat inflexible in terms of opening hours. This has not mattered too much as far as much of their business is concerned, but it does create problems for the benighted traveller desperately searching for accommodation at ten o'clock at night. The usual answer has been some form of window display giving the names, locations and phone numbers of local hotels. Over the past few years these have been computerized to some extent: typically, a VDU placed inside the window displays a ‘menu’ of information available: the customer can select the items he wants by pressing various buttons placed on the outside of the window. Although technically ingenious, these displays remain static rather than dynamic: in other words, they do not display current room availability.

These are local services, but a national ‘Book A Bed Ahead’ service has been operated mainly by the larger Tourist Information Centres. This guarantees to find the traveller accommodation at any other location covered by the scheme up to twenty-four hours ahead. It is thus only an advance booking system in a very limited sense of the term. The mechanics are similar to those of the local service: the Tourist Information Centre telephones its counterpart at the desired destination, which then rings round its own local hotels until it finds a suitable vacancy and then rings back. Since this generally involves two long distance telephone calls, the customer has to pay a fee for the service. The system as a whole might be shown diagrammatically as in Figure 45.

In principle, this arrangement could be developed into a national computerized reservations system, with each participating hotel being linked to its local Centre and each Centre being able to access each other's computer. However, many participating hotels either operate incompatible systems or remain non-computerized, so that full realization of the ideal remains very distant, despite some preliminary steps.

Tourist Information Centres might seem to be an exception to the usual rule that intermediaries have to be paid in some way or other. However, this is not the case. Not only are they financed from tax revenue to which the hotel contributes, but establishments have to pay to be listed and sometimes pay an additional fee to become members of the Accommodation Bookings Service.

The Internet

As we have seen, group reservation systems restrict the customer to just one company or consortium's hotels. The Tourist Information Centre system is not limited in this way, but it suffers from resource problems which reduce its usefulness. In any case, it still puts an intermediary between the customer and the hotel.

The Internet does away with these limitations, as more and more customers are discovering. Any would-be guest equipped with a computer and a modem can now call up a hotel database covering his proposed destination and select an establishment on the basis of its location, price and facilities. He can use the built-in e-mail facility to check its room availability, make a booking and even pay a deposit by quoting his credit card number, all without having to leave the comfort of his home or office. With a fax connection as well, he can have a confirmation slip printed off. In short, it allows him to select a hotel anywhere in the world and offers him instant connection at minimum cost, with all the advantages of immediate response and a permanent record.

Figure 45 Tourist Information Centre system

Figure 46 Guest-hotel connections via the Internet

Figure 46 illustrates the situation as it is now.

Not surprisingly, the Internet has become a major growth area for hotel marketing. Effectively, a web site puts the hotel's front office in front of the would-be guest, and does away with most of the problems connected with intermediaries. The cost to the guest is limited to the equipment (which he will have bought for other purposes anyway) and the Internet subscription.

The cost to the hotel is somewhat greater, because it also has to join what is called a ‘destination database’ (i.e. a kind of electronic brochure or list of hotels in a particular area). This involves a joining fee, a subscription and possibly the payment of commission as well. If the hotel does not do this, then guests searching the Internet may not come across its name. This development has added a new impetus to what is called ‘destination marketing’, which (as our earlier reference to brochures indicates) is actually a very old concept.

The security of on-line Internet transactions has been a source of some concern. As we have seen, modern hotels seek to guarantee their bookings by asking the customer for his credit card details. Until ‘web transactions’ can be shown to be absolutely safe, many customers will be understandably reluctant to divulge these. The problem affects web commerce as a whole and we can expect to see various sophisticated developments designed to solve it. The aim is to make such electronic payments as safe as handing over cash.

The future

The growth of the Internet threatens all the other intermediaries we have been considering. However, the number of hotels remains immense, and if the example of the airlines is anything to go by, their rates are likely to become more rather than less complicated. Customers will still want help with these, and advice regarding destinations in general. In the same way, the convenience of the specialized services offered by tour operators, hotel booking agencies and the like should continue to ensure their survival.

Moreover, people will still make last minute travel decisions, and travellers will still be benighted by unforeseen events such as fog and strikes. In other words, there will always be a role for that oldest and most direct of all booking methods: the last minute walk-in.

Selling to intermediaries

We have seen that intermediary booking agencies such as airlines, group tour operators and conference booking agencies are able to deliver large numbers of guests. It is thus well worth investing time and effort in trying to ‘sell’ the hotel to them. This is not usually part of the job of the front office staff, but hotel sales and marketing departments are increasing in importance and you may find yourself involved in that side of operations one day. You should thus have some idea of what is involved.

The activity can be looked at under two headings:

![]() Direct sales

Direct sales

![]() Negotiating

Negotiating

Direct sales

The difference between direct sales and the kind of selling you do in front office (which we looked at in our last chapter) is that instead of waiting for the customers to come to you, here YOU go to them.

The first step, therefore, is to decide who are to be your sales targets. You have to analyse your sources of business, both actual and potential, so that you can increase the former and penetrate the latter. This comes under the heading of market research, which is dealt with fully in a number of excellent marketing textbooks.

The one point we would stress is that such research doesn't stop with the construction of the hotel or the preparation of the annual marketing plan. It should be a day-to-day activity. Does the local paper contain a report of a forthcoming event? It doesn't matter what this is: it can be a one-off centenary, an annual festival or a dog show: the question should be, is there any business in this? And just who would be able to deliver it? The organizers, perhaps, the local travel agents, or the local Tourist Information Centre? Again, weather forecasts are worth watching. If fog is expected, the airline schedules might well be disrupted, and they and the tour operators may be in the market for beds. National or international transport strikes can have the same effect.

The targets for direct sales include travel agents, tour operators, exhibitors, short course organizers, conference organizers and local businesses, who often make a whole series of bookings for their visitors throughout the year. How do hotels go about selling to these individuals?

First, they find out who is the decision-maker. Sometimes these are professionals who are easily identified, but quite often businesses delegate the organization to somebody relatively junior. Organizing committees present yet another kind of problem, since it is very often difficult to know precisely who carries the main ‘clout’. A great deal of effort goes into lobbying the representatives of the major national and international associations. This is a job for professionals and is outside the scope of this book, but the essential principles remain the same: discover who really makes the decision and concentrate your efforts there.

Next, they choose the most appropriate method of approach. There are a number of these, and, like many other things, they are best used in combination. Let us look at them.

Direct mail

‘Direct mail’ is the term used for the kind of circular letter outlining some opportunity or other which we often find in our morning post. It is superior to advertising in that it can be addressed to a specific group of people and can outline a particular selling point in considerable detail. Take as an example a hotel introducing a complicated new weekend break tariff. It would be wasteful to advertise this nationally because the message would reach a lot of people who wouldn't be interested no matter how persuasive it was. By contrast, a direct mail shot could be aimed precisely at the travel agents, who would then have details of the new offer in front of them.

The problem with direct mail is that people often throw the contents away unread. This is partly because circulars are often perceived as being impersonal. You can get round this to some extent by using the mail merge facilities on your computer to produce personalized letters, but this still doesn't solve the other basic problem, which is that your letter may be seen as irrelevant. This is because there is no guarantee that it will arrive just at the time the recipient is about to make a decision. People don't throw away direct mail related to their immediate problem. Timing is thus crucial.

This brings us back to market research. One of the key things you need to know is when these key decisions are made. Conferences are often arranged months or even years in advance, for instance, so there's no point in sending out direct mail soliciting bookings for next week.

Moreover, experience suggests that there's not much point in sending out just one mail shot, either. Direct mail makes its point by repetition, so if you are targeting a particular group of people you should send out three or more ‘shots’, starting well in advance of their decision date, repeating your basic message but emphasizing something slightly different each time.

Letters

Unlike the circular, a letter is addressed specifically to one particular reader. It is a good deal more flattering to the recipient because he usually has a pretty good idea of how much it actually costs to draft and type. You can emphasize this by adding some kind of personal touch like ‘It was nice to meet you at the conference last month...’. This has become even more important lately, since technical developments are making the better quality ‘personalized’ circular letter increasingly difficult to distinguish from the real thing.

In the old days, letters tended to be fairly formal, with a lot of phrases like ‘We beg to assure you’ and ‘I enclose herewith’. The modern trend has been towards simpler, more colloquial sentences, but one thing hasn't changed, and that is that the letter should look and feel impressive. Good quality paper, an impressive heading, wide margins and clear type all convey one clear message to the recipient, and that is quality. Spelling and grammar need attention, too. It is no use having an impressive letterhead and expensive paper if the letter itself says something like ‘We got sum luvly rooms...’

Letters should be simple, direct and, above all, orientated towards the recipient. He's not interested in your facilities: he's interested in satisfying his requirements, and the only reason he is reading your letter is that he thinks you might be able to help him. He knows, too, that he is going to have to pay something for this service, so don't try to hide the price. Wrap it up by all means (remember ‘the sandwich’?), but let him know it fairly early on so that you have space to cover all the nice things he is going to get for it.

Finally, personalize your signature. You're not just ‘A. Clerk’, you should be ‘Angela’ or ‘Alan Clerk’ or whatever your full name happens to be. No matter how friendly the tone, a letter is still a relatively cold and formal means of communication. This suits some situations, but it isn't ideal for selling. Other things being equal, a customer will buy from the friendliest salesperson available. You can demonstrate that friendliness by inviting your prospective client to use your first name. That doesn't mean that you should use his, of course. A touch of deference at the start doesn't do any harm.

Telephone selling

The first big advantage of telephone selling over letters is speed. It takes time to draft and type a letter, time for the Post Office to deliver it, and often time for the recipient to get around to reading it. Most businesspeople will drop what they're doing in order to answer the telephone. That gives you your opportunity.

The second great advantage is personalization. A letter is just a piece of paper and it is easy to throw in the wastepaper bin because the writer isn't there to see it happening. A telephone caller is a PERSON, and there's no way to cut off a call brusquely without giving offence. Some businesspeople don't mind doing this, but most try to be reasonably civil. Again, much depends upon timing. You stand a far better chance of being listened to attentively if you have got the timing right and you can show that what you are offering will solve one of your listener's immediate problems.

Telephone selling is difficult, and, like all difficult things, it needs both preparation and practice. Let's consider how you should prepare.

1 Identify your target. Make sure you know exactly who you want to talk to, and get through to him yourself instead of getting your secretary (if you have one) to do so. After all, you are making an unsolicited call and you don't want to waste your target's time by making him wait for you to come on the line. For the same reason, try to avoid interrupting him if he is involved in an important meeting. Make an ally of his secretary first: one of her jobs is to protect her boss from time wasters, and she will be inclined to favour a caller who understands her importance.

2 Plan what you are going to say. What questions do you want to ask and what information do you want to convey? List your main points (on one sheet of paper) and work through them briskly but thoroughly. Have a pencil handy and tick them off as you deal with them: after all, your prospective client may ask questions of his own or volunteer information in the ‘wrong’ order as far as your list is concerned, and you have to be flexible.

3 Relax. This is easier said than done, but there are relaxation techniques and you should find one that works for you. Try to sound easy and natural, and don't push too hard.

4 Personalize. Use short, simple sentences and try to stress the key words ever so slightly. What key words, you ask? Well, your listener's name, for instance, your own first name (that friendly touch, remember?), your own establishment (stress the word ‘hotel’ rather than its name at this point because you want to get him thinking about accommodation (he probably has lots of other problems too), and take every opportunity to say ‘you’. For instance: ‘Good morning, Mr CLIENT. My name's ANGELA Clerk and I'm calling from the Smoothline HOTEL. Am I right in thinking that YOU hold an annual sales conference in July? Good. Well, I realize that YOU will have made arrangements for this year, but I'd like to tell YOU what we can offer for YOUR future conferences.’ Notice how this tries to bring the client into the conversation as quickly as possible, even if it's no more than a non-committal ‘Yes’ at this stage.

5 Follow up. This is where the letter comes into its own. Telephone calls leave no permanent record. However, you have made a personal contact, and you can capitalize on that with a personalized letter. The letter also allows you to spell out what you have to offer, and to include whatever brochures or tariffs the contact requires.

Personal calls

The personal call is potentially the most effective means of all, because you are dealing with your target on a face-to-face basis and can interpret and respond to every nuance of expression (remember the importance of being able to ‘read’ body language?). Moreover, you can take all the information you need, select and emphasize exactly those features the discussion calls for, then leave your brochures or price lists for the client to consider at leisure.

Everything we have said about telephone selling applies to personal calls. You have to identify who you want to talk to and then get in to see him, so you will need the co-operation of his secretary just as you did when you were telephoning.

You should plan what you want to say and try to say it as smoothly and persuasively as possible. There's a problem here in that it isn't as easy to refer to a checklist as you can with telephone sales, though if the visit is a follow-up to a phone call during which the prospective client has raised certain points, it is permissible to refer to your notes. After all, this shows that you are taking him seriously.

You should also try to structure the discussion so that it focuses on your client's specific problems and interests. If you are trying to sell your hotel to someone organizing some kind of senior citizens’ get-together, the fact that you have child-minding facilities is likely to be irrelevant at best and positively off-putting at worst.

Finally, you should follow up with a letter, just as you did with the phone call.

Salespeople making personal calls should be fully equipped with all the information they need. A glossy presentation folder with colour photographs of the accommodation, floor plans, sample menus, wine lists and copies of letters from satisfied and prestigious clients is ideal.

All this assumes that you are calling on the client. It is, of course, much better to persuade the client to call on you if you can. This not only allows him to see what you have to offer, but also capitalizes on one of the hotel's biggest advantages, namely, that it offers hospitality. Of course, any reasonably intelligent client knows this, so what is offered has to be of the very highest standard. The slightest slip-up will lead the client to think ‘If that can happen when they're really putting themselves out to impress me, what would it be like when it's just another function?’

Negotiating

The other great difference between selling to intermediaries and normal front office sales activity is that the former usually involves negotiation. Of course, some individual customers may try to bargain over the price, but negotiating is a much ‘larger’ activity, implying approximately equal status between the participants and often involving complicated trade-offs between different elements of an extensive ‘package’ of services.

A typical example of a negotiating situation arises when you are approached by a tour operator. He wants inclusive accommodation at a reduced price over your peak period: you want him to take as many rooms as possible during the months when you are less full. There is a lot of room for discussion here: the type of rooms offered, the cost and range of choice of the meals supplied, the ratio of peak to off-peak period rooms, the price to be paid for the package as a whole and even the number of complimentary rooms to be conceded will all enter into the equation.

Negotiation is the process by which two parties seek to resolve their differences and reach agreement. It implies that they both have an interest in agreeing. However, it also implies that they have different interests. When you start the negotiating process, you will have some idea of your most favourable position (MFP, i.e. the best possible outcome as far as you are concerned). You will also have some idea of your limit (i.e. the least favourable outcome you are prepared to accept). Your opponent will also have similar positions. Hopefully they will overlap, leaving an area in the middle which is called the ‘bargaining arena’ (see Figure 47).

If there is no overlap, then you are not going to be able to reach agreement unless one side or the other revises its limit.

The process of negotiating is so important that you should study it in much greater depth if you find yourself involved in it seriously. In outline, however, you should go through the following steps:

1 Prepare. Try to predict your opponent's limit (don't bother to preguess his most favourable point because he will probably start with that anyway!). Establish your own objectives and make sure that you have all your own facts and arguments ready.

2 Argue. You won't be able to persuade your opponent unless you produce reasonable arguments, so have these ready. Don't make the mistake of thinking that argument means repeating your own point of view in increasingly louder tones. It doesn't. It means listening to what your opponent says, and then producing counterarguments to show him where he is wrong. This is best done in quiet and reasonable tones because shouting will merely get him angry too.

You can call on our old friend body language here. Remember that leaning forward shows interest and that ‘open’ hands and arms indicate sincerity and a willingness to consider your opponent's points, whereas leaning back with your arms and legs crossed demonstrates a closed mind. You may find it useful to use the latter position as a tactical ploy occasionally, but on the whole you will do better with the first.

3 Bargain. Negotiation implies movement. Your MFP and his limit are unlikely to coincide, so be prepared to concede some points. Don't do so at once (‘sell high’, remember?), but don't be too obstinate either. Try to link these to corresponding concessions on his part (‘Look, if you agree to take up more rooms in October, then we can reduce the price by £10 per head...’). Notice the IF YOU... THEN WE... structure of this sentence, which follows the classic ‘cost/benefit’ selling sequence. In other words, don't give anything away free. Concede your least damaging points first, but try to keep one up your sleeve as a ‘sweetener’ that you can throw in to make the final agreement more acceptable to your opponent.

4 Close. If you think you are close to agreement, then try to summarize what has been achieved so far, detailing the concessions made by both sides and adding in effect, ‘We've both moved a long way and it would be a pity not to agree now that we're so close, don't you think?’ If your opponent says ‘Yes’, then you are practically home and dry. This is the moment for your ‘sweetener’. If he says ‘Yes, but...’ and brings out one last objection, then pin him down with something like this, ‘Are you saying that if we move a bit more on that point you would agree?’ The idea here is to get him to commit himself to one last reservation: deal with that and he will find it difficult to stall any longer.

5 Sum up. Never rely on an oral agreement. Get the points down in writing. Send your opponent a letter detailing these as quickly as possible. Make sure that the wording shows that these points were agreed and are not open to further discussion.

Figure 47 The negotiating process

Assignments

1 Collect five different examples of hotel advertising (note: by this we mean examples of the hotel's accommodation being advertised to the public at large, and not just specimens of what we might call ‘internal’ promotions, such as leaflets drawing guests’ attention to special events in the restaurant). Annotate your examples (which could be cuttings, photographs, etc.) with the answers to the following questions:

Where did the advertisement appear?

What was the target market?

What were the key points of the advert (e.g. ‘image’, price, etc.)

Were they: (a) informative; (b) persuasive; or (c) some other category?

What was the approximate cost of the advertisement?

2 Choose either the Tudor or the Pancontinental Hotel and prepare a direct mail shot to attract new short weekend break business.

3 You are front office manager for the Pancontinental. You have learned that the management of Marberry plc, a large local manufacturing business, is planning a training course for its sales executives to introduce them to a new portable computer system which it proposes to introduce. Draft a letter to the sales manager of Marberry with a view to securing this business.

4 Using the data in Assignment 3, prepare and make a sales call to the Marberry sales manager. (Note: this is a role playing exercise. One member of the group should take the role of the target's secretary and another that of the target.) The exercise can be repeated with the following variations; (a) target receptive to proposal; (b) target busy with important meeting but prepared to be receptive when finally contacted; (c) target has already signed contract with another hotel.

5 Compare the roles of Croup Reservation Systems, Tourist Information Centres and the Internet in bringing prospective guests together with suitable hotels.