Chapter 6

Social skills

Introduction

Most experienced hoteliers agree that ‘social skills’ are an essential qualification for front office work. But just what are these social skills, and how can you develop them?

Being ‘skilled’ means possessing the ability to achieve a specific objective efficiently. We all know what we mean by ‘typing skill’, for instance (the ability to produce acceptable quality text, without taking all day over it or spoiling a dozen sheets of paper in the process), or ‘cooking skill’ (the ability to produce food that is both edible and appetizing).

Social skills come into play when we start dealing with other people instead of typewriter keyboards or kitchen ingredients. We still have an objective which we want to achieve (we would like the other person to do something for us, for example), but we have to employ words, expressions and gestures in order to achieve it. Social skills, in short, involve combining these elements in such a way as to influence other people's attitudes and behaviour.

Most of us learn how to do this reasonably competently through the normal process of growing up and interacting with other people, but there is always room for improvement. Learning how to use social skills really well takes lots of practice, but the essential starting point is being able to interpret the basic elements of behaviour: in particular, those small but significant clues to people's states of mind that go under the general term ‘body language’.

These states of mind can vary. Some customers are easy-going, while others seem to be impossible to please no matter what you do. Understanding why people differ like this is a matter for the trained psychologist, but we need to have some means of recognizing what mood a customer is in, and a set of techniques for modifying this if necessary.

Like any other kind of skills, social skills can only be developed through practice. Since they involve social interaction, this practice needs to take the form of unscripted face-to-face conversations, or ‘role-playing exercises’. We have provided a set of situations which require you, as receptionist, to devise appropriate responses. The important thing to remember is that it is not so much a question of what kind of solution you come up with as how you go about communicating it that counts.

Behaviour

We have used the term ‘behaviour’. We must now examine this in greater detail. Let us start with a simple illustration.

Example 1

Imagine you are a guest entering a hotel for the first time. You booked your room some weeks ago and have received the normal letter of confirmation. You approach the reception desk.

The receptionist (Figure 37) keeps her head down. She appears to be checking some figures. You wait for a minute or two, and then you cough to attract her attention. Without looking up. she says. ‘Just hold on a moment, can't you?’ and continues with her calculations. You have plenty of time to study her closely. You see that her hair is dull and she has dandruff. Her nails are chipped, and the collar of her uniform blouse is frayed and a little dirty.

Eventually she says, ‘Yeah?’ You tell her your name and show her your letter of confirmation. She adds a pencil tick to a list in front of her and then puts a registration form in front of you. ‘Fill this in’ she says, then leans forward, arms crossed, to watch while you do it. When you have finished, she takes the form and slaps a key onto the desk. ‘Room 407’ she says, and goes back to her checking.

Now, what kind of impression have you formed of this hotel?

Well, we suspect that it was a pretty poor one. It doesn't matter that you have only been in it for a couple of minutes, or that it seems to have handled your original booking efficiently enough. The receptionist's behaviour has probably been enough to put you off, and it will require an exceptionally high standard of subsequent service to make up for this initial impression.

Note that term ‘behaviour’. One of the key ideas in social skills is the distinction between ‘attitudes’ and ‘behaviour’. If you were asked to describe the receptionist's attitude, you would probably use terms like ‘rude’, ‘surly’, ‘inhospitable’, ‘unwelcoming’ or ‘couldn't care less’, and you would be right. But what gave you this impression?

The answer is the lack of attention she gave to dressing and grooming herself, the way she kept you waiting while she went on with her own routine work, her unwillingness to raise her head to look at you, and her failure to add simple phrases such as ‘Good day’, ‘Can I help you?’, ‘Sir’, ‘Madam’, or to use your name (which she could have seen on the letter you showed her). This is what we mean by ‘behaviour’, and it covers what people do, what they say, and how they present themselves.

‘Behaviour’ is all that we have to go on when we are meeting other people for the first time, especially when we don't know anything about them in advance. This is the usual situation when a receptionist is greeting a new guest, so it is worth looking at behaviour in more detail. It is made up of the following elements.

Self-presentation

This covers dress and grooming, which tell us a lot about other people even before they open their mouths. You should be able to ‘read’ these subtle and constantly changing statements, and you must remember that other people are equally skilled at this process and are busy ‘reading’ yours. Many hotels require their staff to wear some kind of uniform because this acts as a signal, telling the guests that you are there to help them. Conventional business dress can convey much the same message, especially when you are to be seen in a position reserved for employees, such as standing behind the desk. Notice that term ‘conventional business dress’. We have no intention of trying to lay down what this consists of, because fashions and ideas about clothes are constantly changing, but there is usually a broad measure of agreement about what it comprises at any particular period (you probably conformed to it when you bought the traditional interview suit). The point is that whatever the guests’ reasons for being there might be, you are there as an employee, and you need to ‘signal’ this. Not only that: you ought to look as if you take your job seriously and are proud of your role. If you don't, the guest is likely to get a poor impression of both you and your employer. The receptionist in our example was wearing a uniform blouse, but its state suggests that she didn't think very highly of the job it stood for. Nor did she care very much about the kind of impression she was likely to make on the customers: either it didn't occur to her that they might think ‘A dirty, untidy receptionist probably means dirty, untidy rooms, restaurant and kitchen’, or else she didn't care. Is this the kind of impression she should have been trying to give?

Position

Where we stand is important, not only in relation to equipment such as the desk, but also in relation to the people we are dealing with. We all have our own area of ‘personal space’, and any invasion of it by a stranger makes us feel uncomfortable. This personal space varies with status (note how we often talk about ‘keeping our distance’), and also from culture to culture.

This concept of position can be taken further. Whenever people find themselves sitting or standing directly opposite each other with a desk or table in between, they unconsciously divide the barrier into two equal ‘territories’. When our receptionist slapped the registration form in front of you and then leant forward to watch you filling it out, she was invading your personal space. This kind of invasion makes people feel uncomfortable, even if they don't know why, and it should be avoided.

Posture

This covers how we stand or sit in relation to other people. Facing somebody usually indicates interest, and leaning forward shows even greater interest (unless it involves an invasion of personal space, of course). More subtly, we can use our limbs to ‘point’ our bodies in the direction of the person we are interested in (study couples sitting side by side in pubs to see this mechanism in action) or we can use them as ‘barriers’ to shut out people we feel nervous or apprehensive about. Our receptionist began with her body half-turned away and her arm up forming a shield. When she leant forward to watch you filling in the form she was showing some interest, certainly, but even then she kept her arms folded defensively, which conveyed the impression that she wasn't very anxious to help you.

Gesture

This is closely linked with posture, and covers the way we send signals by moving parts of our bodies, mainly our hands, arms and shoulders. A shrug can be very irritating because it suggests that the shrugger is unconsciously trying to ‘shake off your problem. Hands are particularly important. The open palm is not only an age-old sign of friendship (‘Look, no weapons’) but also an indication of honesty. Conversely, a lot of hand-to-face gestures like touching one's mouth or nose can indicate a degree of deceit, or at least some kind of negative feeling, such as doubt, apprehension or uncertainty.

Propping one's head on a hand (as our receptionist was doing when you arrived) often indicates boredom. Is this the impression she should have been conveying?

Expression

The range of possible expressions is immense, but we can generally recognize friendliness when we see it. The mouth curves upwards in a smile and the eyes crinkle a little at the corners. It is unsettling to be met by a stare coupled with a blank, expressionless face, and even worse to be greeted by a sullen expression (lowered brows, a closed, downturned mouth and slightly pouting lips). Try running through our receptionist's routine again, and then ask yourself what sort of expression did you put on when you were doing so. The odds are that you automatically put on a frown, or at least found yourself deliberately adopting a blank, uncaring look.

Eye contact

This is of enormous importance. Looking at someone usually conveys not only interest, but also liking, and the longer arid more frequently you look, the more strongly you are likely to convey these impressions (though a long, unblinking stare coupled with a grim expression can convey aggression). A dishonest person will generally avoid meeting your gaze (but then so will someone who is timid and nervous, which just shows how difficult it may be to interpret behaviour at times). The direction in which you look is also important. The so-called ‘business gaze’ concentrates on the eyes and forehead in order to maintain a serious, rational atmosphere. The ‘social gaze’ moves between the other person's eyes and mouth, indicating a greater interest in reactions such as laughter. A receptionist needs to know which of these types of gaze to choose in respect of any particular guest, and also how to avoid the so-called ‘intimate gaze’, which moves between the other person's eyes and body, and signals rather more than mere social interest! Our receptionist avoided any form of eye contact at all during the first stages of the encounter, and so conveyed a strong impression of lack of interest. Even when she did lean forward, she kept her eyes focused on the registration form, and as soon as you had finished, she turned her head away, dismissing you completely.

Speech

Obviously, what you say is of enormous importance. Using phrases such as ‘Good evening’, ‘Can I help you?’ and ‘I hope you enjoy your stay’ is the clearest way of expressing your interest in your guest's welfare. Perhaps most important of all is to use the guest's name. ‘Sir’ or ‘Madam’ are all very well in their way (at least they indicate respect), but using the guest's name shows that you recognize him or her as an individual and not just an anonymous member of a group you are employed to cater for.

Obviously a good memory is a help here (being genuinely interested in the guests is even better), but there are various ways in which you can help yourself to use guests’ names more. Some form of guest history record is a valuable aid, for instance, and you can always take a quick glance at the guest's registration card. ‘Thank you, Mr Jones. Your room is number 305...’ works wonders. Our receptionist missed two chances. You showed her your letter of confirmation, remember, but she failed to use your name, even though she must have noted it in order to check you off on her arrivals list. Then she watched you fill in the registration card, but she still didn't bother to use your name when she was handing you your key. As far as she was concerned, you were clearly just an anonymous nuisance.

Non-verbal speech elements

It's not just what you say, it's how you say it. You can say ‘Good evening, sir’ loudly or quietly, quickly or slowly, flatly or brightly. You can bring it all out together, or you can insert a pause (‘Good evening ... sir’), which tends to suggest that the ‘sir’ was an afterthought you are not sure the guest deserves. You can lift your tone a little at the end and so turn the phrase into a question (‘Good evening, sir?’), or you can lower it, as you might if you knew your guest had been waiting a minute or two and you wanted to deter any possible arguments by combining your civility with firmness. Accent used to matter, but things have changed, and we don't think that this is true any more as long as you can be understood clearly. What really matters is your TONE. Is it ‘bright’ and ‘friendly’, or is it ‘dull’ and ‘sullen’? And does it sound just as bright at the end of a long and tiring shift as it did at the beginning?

Behaviour and social skills

How do these behavioural elements combine to form social skills? Well, studies indicate that successful practitioners use:

![]() Positions and postures indicating agreement, such as leaning forward and facing their companion.

Positions and postures indicating agreement, such as leaning forward and facing their companion.

![]() Gestures which indicate agreement, such as nods.

Gestures which indicate agreement, such as nods.

![]() Frequent smiles.

Frequent smiles.

![]() Lots of eye contact.

Lots of eye contact.

![]() Phrases which demonstrate an interest in the other person, concentrate on common interests, and adopt the other person's terminology and conventions.

Phrases which demonstrate an interest in the other person, concentrate on common interests, and adopt the other person's terminology and conventions.

![]() Overall, a smooth, easy pattern of interaction, with few pauses or interruptions.

Overall, a smooth, easy pattern of interaction, with few pauses or interruptions.

Social skills have an important part to play in front office work. Service is about meeting the guest's psychological needs and making him feel welcome, and social skills are an essential part of this process. A receptionist might use them to calm down an irritable guest, for instance, or to make a nervous one feel welcome. Social skills can be used for selling purposes, too, but we will look at this in a later chapter. For now, we will consider how they can be employed to smooth out the ordinary, everyday contacts between the guest and front office.

Let us consider another situation by way of illustration.

Example 2

It is 5.30 on Thursday evening and you are alone on the desk. You have three kinds of room, singles, twins, and luxury suites. Your bookings chart indicates that your occupancy level tonight is around the seasonal norm of 60 per cent. Your arrivals list is arranged in alphabetical order and includes the following:

LANGLEY J Mr 303

MORRIS P Mr/s 214

NAYLOR T Dr 115

The door opens and you look up to see the man shown in Figure 38.

He strides confidently towards the desk. You smile and say, ‘Good evening, sir. Can I help you?’, and he replies, ‘Yes, my name is Martin. I have a reservation for tonight.’

You check your arrivals list, but you find no such name. At this point you remember (with a sinking feeling) that your colleague Tracy (who handles a lot of advance bookings) has personal problems and has been making a series of errors lately. You ask whether Mr Martin has a letter of confirmation. ‘No, I'm sorry,’ he replies. ‘My secretary only made the booking a couple of days ago, and it hadn't arrived by the time I left.’

What do you do now?

What you would probably say is something like this: ‘I'm very sorry, Mr Martin, but there seems to have been a bit of a mix-up and I can't find your booking. There's no problem, though. What kind of room did you want, and for how long?’

This isn't bad, but it tells the guest two things which present your hotel in an unfavourable light. Firstly, that you have mislaid his booking, which suggests a degree of inefficiency (never mind how true this may be). Secondly, that you are nowhere near full. He may begin to wonder why, and start to look for reasons (in which case he'll probably find a few, since no establishment is perfect). He may also begin to wonder what might have happened if you had been full, since you don't seem to be able to keep track of your reservations even when you're not!

How could you have avoided giving him these ideas?

Well, look at the illustration again and try to guess the answers to the following questions:

1 What kind of room does Mr Martin want? (We think you'll conclude that he wants a single. He seems to be alone, not accompanied, and he looks more like a single businessman than a family man who has a wife and children out in his car.)

2 How long is he likely to be staying? (We think one night. He isn't carrying much luggage, and that's how long single businessmen arriving on Thursdays usually stay, anyway.)

Now, on the basis of those guesses, try the following:

| You: | ‘Just one moment, Mr Martin...’ (Glance down and have one last look for the missing booking. This gives you time to compose yourself.) ‘It was a single room, wasn't it?’ (End your sentence on a slightly rising note, making it half statement, half question.) |

| Martin: | (Thinking that you are simply double-checking, and impressed by your efficiency) ‘Yes.’ |

| You: | ‘For one night...?’ (same vocal inflexion) |

| Martin: | ‘Yes.’ |

| You: | (Confident now) ‘Would you just fill in this form, Mr Martin? That'll be Room 209...’, etc. |

Now, this could go wrong, but the odds are that it won't. Even if it does, you are no worse off than you would have been if you had told Mr Martin right at the start that you'd lost his booking. In other words, a skilled receptionist can often conceal the inevitable error or two by using her social skills.

There is another question which you might need to answer, and that is, ‘How much did Mr Martin agree to pay?’ Let's say your singles are £60, but business discount reduces this to £54. In this case you would be tempted to go on, The rate was £54, wasn't it, Mr Martin?’ As we will see, however, one of the basic principles of sales is to ‘sell high’, so it is better to start at £60. If your guest protests that he was booked in at the discounted rate, it is easy enough to apologize and come down.

Let's go back to the original conversation and look at what you did in more detail and in behavioural terms.

When Mr Martin entered, you looked up at him and made a quick assessment, identifying him as a probable guest on the basis of his dress, accessories and general manner. You gave him a pleasant smile and greeted him politely, thus putting him at his ease and helping to establish a smooth pattern of interaction.

At this point it began to go wrong because you discovered that someone had mislaid his booking. However, you didn't display any outward signs of panic or confusion. You lowered your head, ostensibly to double-check your records, but in reality to give yourself time to collect your thoughts. Then you took the initiative. You did this by making a couple of intelligent guesses, and then going on to choose a form of words which could be interpreted as either a question or a statement. You reinforced this ambiguity by the way you uttered them (that rising inflection, remember?). If you were right, Mr Martin wouldn't notice anything unusual, and if you were wrong, well, you had left yourself room for retreat (a quick apology and a correction). The likely result: a satisfied guest and a possible repeat booking.

Notice that there were two parts to the ‘solution’ in this example. The first was the ‘social skills’ aspect, which enabled you to combine the various elements of your behaviour into an effective pattern of interpersonal interaction. The second was what we might call ‘technical’ knowledge. This covers your familiarity with your hotel's room and tariff structure, its current advance bookings situation and normal occupancy pattern, the habits and expectations of the single business guest, etc.

Most guest-reception contacts are straightforward, and their ‘technical’ aspects soon become second nature. Guests arrive: the process of checking them off, inviting them to complete the registration process, and assigning rooms soon becomes automatic, allowing you to concentrate on them as people. This helps you to add the important ingredients of a friendly greeting, a smile, and ideally some kind of personal touch (‘Nice to see you again, Mr Johnson. How have you been keeping...?’).

Every now and again there will be a problem. Some of these will involve ‘technical’ aspects, others won't, but they will all require delicate and sensitive handling. The essence of most problems is that the customer wants something which for one reason or another you can't let them have. Perhaps it is someone who wants a type of room which you know happens to be fully booked, or a couple who want to vacate their room later than your housekeeping staff find convenient, or a guest who feels inclined to make more noise in his room than your other guests are prepared to accept. In all these cases the question is the same: can you find a solution acceptable to both the guest and the hotel, and if not, can you manage to persuade the guest to accept an alternative with the minimum of fuss and disturbance?

Remember, all you have at your disposal are the various elements of behaviour: what you say, how you say it, and how you appear to the other person while you're saying it. It helps:

1 If you have already worked out the possible ‘technical’ answers as far as you are concerned (can you accommodate this ‘chance’ guest? Can you move that one to another room?).

2 If you have also anticipated what the other person's reactions are likely to be (are they really likely to complain if they don't get their way?).

Obviously, you ought to be familiar with as many aspects of your hotel's operation as possible. However, many reception problems actually involve little or no ‘technical’ knowledge at all. Consider the following example.

Example 3

It is 5.45 p.m. and you are alone on the desk in a busy provincial hotel with a mixed clientele. There is a small queue of guests waiting to check in. At its head is a young and attractive female guest who has booked a single room as an independent traveller. Behind her are three equally young businessmen whom you are reasonably sure belong to a sales managers’ conference which you know is being held over the following two days. They are clearly interested in the female guest, and she is equally clearly NOT interested in them.

How would you handle this situation?

Now, what is your objective here? It should be to defuse a potentially awkward situation for one of your guests. Clearly, there is a risk that the young men will pester the unaccompanied female, and it would not be a good idea to let them discover either her name or (especially) her room number. They could find these out fairly easily by looking over her shoulder while she registers. Can you prevent this? Well, you might try the following:

You: (To male guests) ‘Excuse me, gentlemen, are you waiting to register? You are? Well...’ (Moving along the desk away from the female guest) ‘Perhaps you'd just like to fill in these forms here while I deal with the other guest...’

This combination of words and action not only moves the three boisterous males away from the single female, but it also gives them something else to do while you are dealing with her. You are making it difficult for them to overhear her name, or her room number, or her home address, or how long she is staying. You can pass her the room key (assuming you are still using the non-computerized kind) in such a way as to conceal its number. She might not notice what you have done, of course, or say anything even if she does, but you will still feel the satisfaction that comes from having handled a difficult situation skilfully.

This is just as much a part of the receptionist's job as taking bookings, or presenting bills. In fact, many hoteliers would argue that it is a more important part. It requires no special knowledge of front office procedures, but it does require the ability to recognize potentially awkward situations, and the skill and confidence to take appropriate action.

One of the problems associated with the behavioural approach is that the elements of behaviour do not constitute a single, mutually understandable worldwide ‘language’. As we all know, spoken and written languages vary considerably from one culture to another. The language of gesture varies in much the same way. There are large areas of the Middle and Far East, for instance, where giving someone something with the left hand is considered to be offensive in the extreme, and you would do well to remember this when you are handing over a registration card or a room key to a visitor from those regions.

This point has been made by writers like Michael Argyle and Desmond Morris, but personal experience is always more convincing than textbook examples, however authoritative. One of the authors of this book once worked on a small Caribbean island. The economy depended heavily on tourism (as in most of the islands), and the government was naturally anxious to know whether the tourists (mostly middle-aged North Americans) felt that they were getting good value. It therefore invited them to fill in exit questionnaires.

The results were disquieting. The tourists generally agreed that the scenery was beautiful (as it indeed was), the food good, the hotels comfortable, the sporting and other recreational facilities satisfactory, and the availability of handicrafts and other mementoes adequate. However, the majority said that the service staff (in shops, bars and restaurants as well as the hotels) were ‘sullen and hostile’, and when asked whether they would recommend the island to their friends or come back themselves, a considerable number said ‘No’.

Naturally, this worried the government, and it got together with other governments and commissioned a survey. The investigators found that while there was a small amount of genuine hostility (not surprising in view of the islands’ histories), the tourists’ belief that the staff were sullen and hostile was largely based on a genuine misunderstanding.

Children in the islands were brought up to behave in a particular way when in the presence of someone who might be considered a social superior. They were taught not to speak first, but to wait to be addressed. They were not supposed to look directly at a superior, or to smile (unless smiled at first), but rather to look downwards and to adopt a serious expression.

Try this for yourself. Place yourself behind a desk or counter, and wait for a companion (the ‘guest’) to approach you. As he or she does so:

![]() Take a half step backwards.

Take a half step backwards.

![]() Turn your upper body a few degrees AWAY from the ‘guest’.

Turn your upper body a few degrees AWAY from the ‘guest’.

![]() Lower your head and direct your eyes towards the guest's feet rather than his or her face.

Lower your head and direct your eyes towards the guest's feet rather than his or her face.

![]() Adopt a serious, even solemn expression.

Adopt a serious, even solemn expression.

![]() Remain silent until addressed.

Remain silent until addressed.

Now, ask your companion (who is playing the role of a North American tourist) what impression this behaviour has created, taking into consideration his or her cultural standpoint.

If you think about it, North Americans are accustomed to staff who step forward smartly, look them straight in the eye, give them a broad smile of welcome, and initiate the exchange with some such phrase as ‘Good morning, can I help you?’ The behaviour YOU have just imitated is the opposite in every respect. No wonder it was perceived as demonstrating sullenness, hostility and an unwillingness to be of service! In fact, as we hope you have realized, it was simply the local way of being polite.

The government tried to solve the problem by arranging seminars and training courses for hotel receptionists and other service staff. Other islands experienced much the same problem, and one launched an intensive advertising campaign with the theme ‘Every smile means a tourist dollar’. The fact that it spent scarce resources in this way indicates that it saw this kind of misunderstanding as a serious problem, and if you have read this chapter carefully you will not be surprised to see that they adopted a ‘behavioural’ solution by trying to get the staff concerned to act in a different way when faced with North American visitors.

This example reminds us that behaviour is only meaningful within a given situational context. Nevertheless, as far as most guests are concerned, your normal or instinctive approach is likely to be perfectly adequate.

Role play assignment

Introduction

We have seen that front office staff not only need to be able to handle enquiries, bookings, billing and payments efficiently, but to do so smoothly and pleasantly, using their social skills so that guests are left feeling that their needs have been met and that they have been treated with sympathy and understanding. A further point is that they must be able to deal with guests in ‘real time’, often without any preparation, and frequently without being able to call on more experienced colleagues for assistance.

This is an important aspect of the job, and we have accordingly devised the following role play exercise to help you develop the appropriate skills. The problems vary in terms of difficulty, but this is typical of real life. The exercise works best if you observe the following guidelines:

1 One participant should take the role of the ‘receptionist’ and another that of the ‘guest’. In most cases it is the ‘guest’ who starts off the conversation. It is then up to the ‘receptionist’ to produce appropriate responses in the light of the chart, arrivals list data and other information provided. The problems are open-ended in that the guests’ reactions will depend (as in real life) upon their characters and the receptionist's initial responses.

2 The guest may be either male or female: alternatives are given in the script to cover either eventuality, and the participants should select whichever is appropriate. Guests should display firmness in looking after ‘their’ interests, without setting out to be too difficult. The dialogues will normally be brief, lasting only for three or four exchanges. Both participants should take the exercise seriously. Clowning around and playing it for laughs may seem fun at the time but it is really rather short-sighted. Dealing with guests is a very important aspect of the receptionist's skills, and it should be treated as such.

3 It is a good idea to select both problems and participants on a random basis. This guarantees that the receptionists don't know in advance which particular problem or guest they will be asked to deal with. This is not only more true to life but also fairer in as much as the problems necessarily vary in difficulty.

4 Participants should be able to read through the problems first so that they can work out any ‘technical’ implications in advance (though sometimes there aren't any: it is just a matter of applying common sense). As receptionists they should be concentrating on the social skills aspects. It's not so much knowing what to say that's important here; it's knowing how to say it.

5 The exercise itself should be ‘unrehearsed’. In other words, the receptionist and the guest shouldn't get together beforehand to work out how the rest of the conversation should go. Effective social skills involve reacting to unexpected initiatives, and you need to practise this aspect.

6 The exercise should be conducted in front of an audience (e.g. the rest of the group). This is because you are trying to develop a kind of ‘performing’ skill, and while solitary rehearsals are all right if you are simply learning your lines, they are no substitute for the real thing. Once the exchanges have come to a natural end, the discussion can be thrown open to the group. As observers rather than performers, they will have seen more than either the receptionist or the guest, and they can provide valuable feedback and suggestions. It is even better if you can arrange to have the roles acted out in front of a video camera so that you can play the tape back later. We often have no idea of how we appear to others until we have seen ourselves in action in this way.

7 Although the problems are shown as occurring one after another, they are not meant to be linked for role play purposes. This means that the chart should not be updated as the problems arise. Experience indicates that this becomes too confusing.

8 In some situations (e.g. bookings or re-roomings) it is a good idea to get the receptionist to explain how he/she plans to accommodate a particular guest. In this context the instructor can play the part of the front office manager: otherwise senior staff are presumed to be unavailable, as they sometimes are in real life.

9 It helps if you can arrange to have a few ‘props’ such as a desk, a key rack, a couple of telephones and some bills or letters of confirmation which have been preprepared along the lines indicated in the dialogues. They aren't strictly necessary, but they do help to set the right ‘pace’ for the dialogues. After all, pauses constitute quite a large part of most conversations, and what you do during them is an important aspect of ‘body language’.

10 Following on from the above, it helps if receptionists take the trouble to look the part. Put on that interview suit and see what a difference it makes to your whole carriage and bearing. That's partly what you are supposed to be practising, isn't it?

11 The receptionists’ performances may be assessed using peer group assessment methods. The criteria can include the question of whether the solution was satisfactory from a ‘technical’ viewpoint (i.e. did it meet the guest's needs, did it help to maximize occupancy and/or revenue, and did it comply with legal or other constraints?), though student groups may need some help in this respect. They are, however, perfectly capable of judging how satisfactory the performance was from a social skills standpoint (i.e. whether the receptionist was fluent, polite, friendly, helpful, welcoming, etc.) We suggest that such assessments should be anonymous, and that receptionists ought to be able to assess their own performances as well as those of their colleagues.

12 A final point. In one or two cases the problems may require the receptionist to determine hotel policy. In reality, you would probably be able to consult a senior manager, but for the purposes of this exercise YOU are the senior manager as well as the person on the spot!

Terms and conditions

The hotel normally sends out confirmation letters but does not ask for deposits. The terms include the following:

![]() No dogs.

No dogs.

![]() Guests must normally take up their bookings by 6.30 p.m. unless the hotel is notified in advance of late arrival.

Guests must normally take up their bookings by 6.30 p.m. unless the hotel is notified in advance of late arrival.

![]() Rooms must be vacated by 12.00 noon on the day of departure. A full day's room rate is due in respect of any day or part of a day that the room is occupied.

Rooms must be vacated by 12.00 noon on the day of departure. A full day's room rate is due in respect of any day or part of a day that the room is occupied.

The problems

(Note: we have graded these in approximate order of difficulty. A ‘*’ means fairly easy, ‘**’ is a bit more complex, and ‘***’ is harder still. The criteria include both the number of issues raised and/or the amount of tact and diplomacy required.)

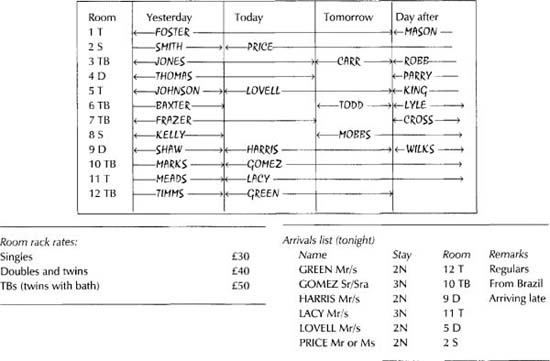

Background data

Bookings chart

Problem 1 (**) Time 7.30 a.m.

Guest : ‘Marks, Room 10. Can I have my bill, please? (Pause) What's this? £50 for the room? But when my travel agent made the booking for me they were told your twins with bath were £40! Look: here's the confirmation they sent me.’

(Shows receptionist the travel agent's letter to Mr and Mrs Marks, which does indeed say ‘Twin room with bath £40’. The receptionist has no record of any special rate being agreed.)

Problem 2 (*) Time 7.45 a.m.

Guest: ‘My name's Shaw, Room 9. My bill, please. (Pause) What's this? £3.00 for the telephone? But I only made one local call! It was after 6 p.m. and I only spoke for a couple of minutes...’

(The receptionist was not on duty at the time but knows that calls are monitored automatically and that the equipment is modern and accurate.)

Problem 3 (**) Time 8.00 a.m.

Guest: ‘I'm Mr (or Mrs) Meads, Room 11. My bill, please’.

(The receptionist has just been told by the housekeeper that the TV set in Room 11 has been knocked off its stand and is not functioning. The set cost £200 when purchased two years ago. The cost of repair is currently unknown. The housekeeper is prepared to swear that the TV was in working order when the room was checked prior to the Meads occupying it.)

Problem 4 (***) Time 8.30 a.m.

(The receptionist has just taken a telephone call from the housekeeper, who says that there aretwo towels (value about £10) missing from the Baxters’ room. Mr (or Mrs) Baxter approaches the desk.)

Guest: ‘Good morning. Baxter, Room 6. My bill please.’

Problem 5 (**) Time 9.00 a.m.

Guest: ‘I'm Mr (or Mrs) Timms. We're checking out, and I'll tell you now that we're NOT paying for that bathroom! There wasn't any hot water, either last night OR this morning, and we weren't able to use it properly. It's a disgrace. I've a good mind to complain to the Tourist Board!’

(The receptionist knows that the hotel has been having some problems with its hot water system and that Room 12 has been particularly severely affected.)

Problem 6 (*) Time 9.15 a.m.

Guest (Bleary eyed and very cross): ‘Kelly, Room 8. I asked for a 6 a.m. call last night but nobody rang me. Now I've missed my plane and the chance of a major deal. It's all your fault!’

(The receptionist can find no note of such a request, but was not on duty on the previous evening. All the rooms have telephone installations which the guests can program to provide themselves with an alarm call, though the instructions are rather complicated.)

Problem 7 (*) Time 9.30 a.m.

Guest: ‘I'm Mr (or Mrs) Johnson from Room 5. I'm afraid we've had to take our car in for repairs and it won't be ready until tomorrow at the earliest. Is it all right if we stay another night?’

Problem 8 (**) Time 10.15 a.m.

Guest: ‘Oh, good morning. I'm Mr (or Mrs) Jones from Room 3. We arrived last night with our daughter and son-in-law, the Thomases, but I forgot to mention that we're travelling together and that we've agreed to pay their bill...’

(The receptionist has been updating the guest bills and is aware that young Mr and Mrs Thomas were in the bar until late last night, charging a considerable number of drinks to their room number.)

Problem 9 (***) Time 10.45 a.m.

A member of the housekeeping staff has discovered undeniable evidence of the use of illegal hard drugs in Room 4 (‘undeniable’ means just that: the Thomases will know that if the matter is referred to the police and they are prosecuted, they are almost certain to be convicted). This discovery has been reported to the general manager, who has instructed the receptionist to insist that the Thomases leave immediately. Mr (or Mrs) Thomas happens to pass the desk.

Receptionist (Carries out general manager's instructions.)

Problem 10 (**) Time 1.45 p.m.

(The receptionist discovers that Mr (or Ms) Smith in Room 2 has not checked out, then sees him (or her) passing.)

Receptionist (Asks why Smith has not left.)

Guest: ‘Oh, I thought I mentioned when I arrived that I wouldn't be leaving until late afternoon...’ (There is nothing in the records to confirm this statement.)

Problem 11 (*) Time 2.45 p.m.

Guest (on telephone): ‘Hello, my name's Parry. We're booked in for the day after tomorrow. I've just looked at your letter of confirmation and I see you've given us a double room. I wonder if you could change that to a twin, please?’

Problem 12 (*) Time 3.00 p.m.

Guest (on telephone): ‘Hi, our name's Forbes. We've stayed at your hotel several times before and we'd like to come again the day after tomorrow. We want a twin with bath, please, and we'd like Room 6 because it's got a particularly nice view.’

Problem 13 (**) Time 3.15 p.m.

Guest: ‘Foster, Room 1. We were booked to stay for another two nights, but we've just had a phone call to say that our house has been burgled. I'm afraid we'll have to check out immediately.’

Problem 14 (*) Time 3.30 p.m.

Guest (on telephone): ‘Hello, my name's Kelly. I checked out this morning. I've just realized I left my watch in the room. It was on the bedside table beside the lamp...’

(The receptionist has already checked lost property with the housekeeper and knows that no watch has been handed in.)

Problem 15 (**) Time 4.00 p.m.

Guest (on telephone): ‘Hello, my name's Price. I was booked to arrive tonight, but I have some business here which is going to delay me and I won't be able to arrive until tomorrow. Is that OK?’

Problem 16 (*) Time 4.30 p.m.

Guest (on telephone): ‘Hello, my name's Franklin. I'm due to meet my mother (or father) at the airport near you the day after tomorrow. Can I have two single rooms, please?’ (Note: Whoever is playing Franklin should quote a parent of the OPPOSITE sex.)

Problem 17 (*) Time 6.00 p.m.

Guest (approaches desk): ‘Excuse me, my name's Lovell. My wife (or husband) and I have just arrived. I'm afraid that although we booked a plain double room, my wife (or husband) hasn't been very well, and we really need one with a private bathroom. Would it be possible to change, please?’

Problem 18 (*) Time 6.15 p.m.

(The receptionist was informed that a burst pipe has made Room 12 totally unusable for the night. A couple approach the desk.)

Guest: ‘Good evening, our name's Green. We have a reservation...’

Problem 19 {**) Time 6.30 p.m.

Guest (approaches desk and speaks slowly, with a marked foreign accent): ‘Er, good evening. My name ‘ees Gomez. I ‘ave reservation.’

Problem 20 (**) Time 6.45 p.m.

Guest (approaches desk): ‘Good evening. My name's Carter and my wife (or husband) and I have a reservation. Here's your letter of confirmation saying that we've booked one double room arriving tonight and staying for two nights...’ (Shows receptionist the hotel's letter, which confirms Carter's statement.)

Problem 21 (***) Time 7.00 p.m.

(A male and a female approach the desk. They appear sober, respectable and well behaved.)

Guest: ‘Hello. My girl (or boy) friend and I have missed our train. Can you let us have a twin or a double room for the night, please? My surname's Hill and my friend's name is Martin.’

Problem 22 (*) Time 7.15 p.m.

(Ms Gold, who is a young female independent traveller, approaches the desk. She is followed by the unaccompanied Mr Green, who obviously finds her attractive. They clearly do not know each other.)

Ms Gold: ‘Good evening. Have you a single room for one night, please?’

(Green crowds up behind and tries to look over Ms Gold's shoulder in an obvious attempt to find out her name, address and room number.)

Problem 23 (**) Time 7.30 p.m.

Guest (approaching desk while partner and baggage head for exit): ‘Mr (or Mrs) Lovell. We'd booked to stay two nights, but I'm afraid it's not at all what we expected, and we want to leave now. We didn't have a meal or anything to drink, so there shouldn't be anything to pay, should there?’

Problem 24 (*) Time 7.45 p.m.

Guest: ‘Good evening. I'm Mr (or Mrs) Thomas from Room 4. You sent your maintenance man up to my room to repair a faulty switch earlier this evening. It took about ten minutes and I was in the bathroom for some of the time. Well, I've just discovered that there's a ten pound note missing...’ (The receptionist knows that the maintenance man has been with the hotel for years and has an unblemished record.)

Problem 25 (*) Time 8.00 p.m.

Guest: ‘Excuse, please. I am Senor (or Senora) Gomez. I am a stranger in this city but I am interested in its history. I go to shop tomorrow. Where is best place to buy old books or prints, please?’

(The receptionist does not know the answer to this question.)

Problem 26 (**) Time 8.45 p.m.

(A guest approaches the desk. He (or she) is respectably dressed but carries no luggage.)

Guest: ‘Good evening. My name's Skipper. I'd like a room for the night. I've just arrived from Paris but I'm afraid my luggage hasn't! You know what airlines are like, ha ha ha!’

(The receptionist is aware that a guest answering to a similar description - though using a different name or names - has left several hotels recently without paying the bill.)

Problem 27 (**) Time 9.30 p.m.

(The receptionist has just let Room 11 to a chance guest on the assumption that the Lacys are not coming. A guest and companion enter and approach the desk.)

Guest: ‘Good evening. Our name's Lacy. We're sorry to be so late, but our plane was delayed and we couldn't phone you...’

Problem 28 (**) Time 10.45 p.m.

Guest (approaches desk): ‘Good evening. Our name is Harris. We reserved a double room some weeks ago and told you we'd be arriving late.’

(The receptionist hears a ‘Yap!’ and notices that the Harrises are accompanied by a small dog. There are no commercial kennels nearby.)

Problem 29 (**) Tomorrow, Time 00.15 a.m.

Guest (approaches desk): ‘Hi, my name's Smart. I'm looking for a single room for what's left of the night. I've just rung the motel on the edge of town and they've offered me one for £20. If you're prepared to come down to something like their price, I'll take one of yours.’

Problem 30 (**) Tomorrow, Time 01.00 a.m.

Guest (approaches desk): ‘Excuse me. I'm Mr (or Mrs) Frazer from Room 7. I'm sorry to bother you, but our room's over the bar and there seems to be some sort of party going on. There's a lot of noise coming from it and we can't sleep.’

(The party is being thrown by the Joneses from Room 3, who are regular and generous guests, and is scheduled to go on until 03.00 a.m. The other rooms are all quieter.)

Problem 31 (**) Tomorrow, Time 03.45 a.m.

(Mr and Mrs Jones have retired to their room, where they are singing, dancing and generally behaving in a noisy and boisterous fashion. The receptionist receives complaints from several other guests. ‘Mr and/or Mrs Jones’ should respond negatively to the receptionist's initial approaches.)

Problem 32 (***) Tomorrow, Time 9.30 a.m.

Guest (in a state of agitation): ‘Me Senor (or Senora) Gomez. We ‘ave bin robbed. We leave our jewellery in locked room while we ‘ave meal. When we come back, window broken, all gone!’

(The basic facts will turn out to be as stated. The window of the Gomez’ room looks out onto a garden which is normally unattended at this time. The window can be reached via a drainpipe, but only by an unusually determined and athletic burglar. No previous thefts of this type have been recorded. The missing jewellery can be assumed to have a value of two or three thousand pounds. The hotel displays the standard Innkeepers Act disclaimer notice in the lobby, and a further notice on the inside of the bedroom doors advises guests to deposit valuables with reception for safe keeping.)