Chapter 7

Sales

Introduction

Most of the expenses Involved in letting accommodation are fixed, so once sales have passed the break-even point additional receipts are virtually pure profit from the department's point of view. This means that effort put into generating additional room revenue is worth more than equivalent effort put into selling liquor or food, where there are important variable costs. Of course, better value for money in terms of food and drink can generate extra accommodation revenue, but the fact remains that in many hotels the bars and restaurants often do little more than break even and it is the rooms which generate the profits.

Raising room revenue is usually seen as a marketing problem. However, there are measures which front office staff can take, and they form the subject of this chapter. The basic point to grasp is that there are two ways of increasing revenue. One is to bring in more customers, the other is to persuade each customer to pay more.

To demonstrate this, imagine a hotel with 100 beds, an average guest rate of £50, and an average annual occupancy of 70 per cent. The average nightly accommodation revenue will be:

70/100 x 100 x £50 = £3,500

Now, let us assume that we can somehow add another 7 per cent to the occupancy rate. The figures now become:

77/100 x 100 x £50 = £3,850

Alternatively, let us assume that we can somehow persuade each guest to pay £5 more. The figures then become:

70/100 x 100 x £55 = £3,850

This example may be somewhat contrived, but it does underline the point that there are two ways of increasing revenue. Combining them gives even better results. If we can increase both occupancies and average spends in these proportions, the figures will then be:

77/100 x 100 x £55 = £4,235!

So let us see what front office staff can accomplish in these areas.

Increasing occupancies

Although front office has little to do with the main means by which guests are attracted to a hotel (advertising and direct sales, for instance), this does not mean that its staff have no scope at all for increasing occupancies.

‘Juggling’ bookings

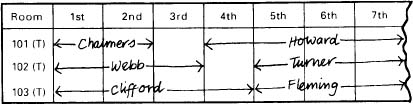

If the hotel uses a conventional chart, skilled reservation clerks can display ingenuity in plotting the bookings so as to fit in the maximum number. We have already looked at this earlier, but to remind you, consider Figure 39, which shows the chart for next month.

Now suppose you receive a request from Mr and Mrs Morrison, who want a twin room for the nights of the 3rd and 4th. An inexperienced clerk may well say, ‘Sorry: we don't have a twin for both nights’. One with more experience would quietly switch the Chalmers with the Webbs, leaving Room 102 free for two nights for the Morrisons.

You can also help to fill a hotel by persuading unrelated singles to occupy twins. Such ‘doubling up’ used to be a common practice in the old days (indeed, guests were often expected to share the same bed!), but it is now much less frequent. However, it still makes sense to try it if you have too few singles and too many twins. Groups such as conference delegates are worth approaching because they may know each other already and are likely to have something in common. An inducement such as a price reduction is well worth considering.

‘Splitting down’ is another practice which can help if business is slow and rooms plentiful. Try suggesting to a couple who want a twin that they might prefer two singles instead. You would have to pick your customers very carefully: this isn't likely to appeal to a pair of obvious honeymooners, but it might suit an older couple who normally occupy separate rooms at home. Two singles (even at reduced rates) should still net you more than one twin.

Handling enquiries

Most shop assistants ask ‘Do you want anything else?’ as a matter of course. Few reservation clerks do. This is a mistake, because a lot of calls come from agents of various types who have to make multiple bookings. It saves them time and money if they can reserve several with one call, and although their other clients may have expressed preferences for other hotels, your question might just tip the scales and lead to them all being placed with you.

In the same way, never respond to a request for a single room on the 15th with ‘I'm sorry, we're full’. Haven't you got anything else you could offer? Your order of priority ought to be:

1 A different type of room. Don't you have a twin you might offer at an appropriately reduced rate?

2 A different date. It is surprising how flexible some guests can be, and if you only win 10 per cent of the time you will still be well ahead.

3 A companion hotel. If you are located in a large city, you may well have one or more ‘sister’ hotels nearby. The relationship is often one of mutual competition, but it makes sense to see whether one of them can take your overflow.

4 Another hotel. If you can't fit your caller into one of your own hotels, then try someone else's. Kemmens Wilson, the founder of Holiday Inns, would not allow his managers to put up ‘hotel full’ signs. Instead, he required them to fix up any surplus traveller at a nearby establishment. As he explained, Holiday Inns thereby made two friends. One was the traveller, who would be likely to return to Holiday Inns again,’and the other was the competitor, which would be more likely to send its surplus to the local Holiday Inn in future.

Repeat business

Another very important way in which front office staff can help to increase occupancies is to try to boost repeat business. Obviously, the guest must have been satisfied with the hotel during his current stay, otherwise you stand little chance of his coming back.

If all has gone well, the moment of departure is a good time to try some forward selling. Many hotels ignore this opportunity, but there are good reasons for trying to capitalize on it. One of the main problems hotels face in terms of marketing is that they are seldom able to engage in face-to-face selling, since bookings are usually arranged in advance, over the telephone and often through agents of one type or another. Never forget that A GUEST IN THE HOTEL IS A POTENTIAL FUTURE CUSTOMER. Somebody who has come to your area once may very well do so twice, and if your hotel suited him then, it ought to do so again.

There is another and more subtle point. A hotel is a kind of home, and departure is often a somewhat comfortless time: the guest has to set off into the cold, unfriendly world once more, and it is at this moment that he is likely to be particularly receptive to the suggestion that you would like to see him back sometime. You can ask ‘I hope you enjoyed your stay?’, and if you get an affirmative answer, go on to ‘Are you going to be coming back this way again? Can we make a provisional booking?’ Even if only a few guests are able to give you a definite answer there and then, you've still planted the idea in the others’ minds, and it may well develop into a firm booking eventually.

The same point applies to the use of ‘follow-up’ techniques. Commercial firms often pay considerable sums of money for address lists which might include a high proportion of potential customers. Your registration cards are just that. These are people who have already had reason to come to your area, have chosen your hotel, and have (presumably) been happy with their choice. We shall return to this point when we look at marketing.

‘No shows’

The most difficult and controversial issue in connection with increasing occupancies is the way you respond to the problem created by ‘no shows’. These are people who make bookings and then fail to honour them. Early departures have the same effect, though they are not quite so serious from the hotel's point of view because you tend to find out mid-morning rather than the late evening, allowing you more chance to relet.

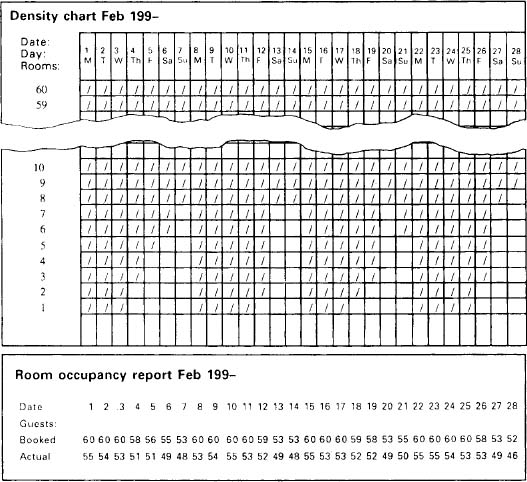

Let us examine the effects of no shows through an example. You are presented with the following (simplified) density chart for a four-week period, together with the accompanying (equally simplified) occupancy report (Figure 40). The average room rate is £40 per night.

What is your room revenue for the period, and how might you increase it?

Well, the percentage of arrivals to bookings averages about 90 per cent. In other words, the no-show rate is 10 per cent, which is five or six guests per night. The effect on room revenue is easy to calculate. The total of actual room nights was 1,454, which yielded £58,160 over the period. However, if everyone who had booked had turned up, you would have had 1,615 room nights yielding £64,600, a difference of £6,440.

Figure 40 Density chart and occupancy report

This is a substantial sum to lose (especially for a relatively small hotel), and as a front office manager you should not be happy about it. But what can you do to reduce the impact of no shows? There are several alternative approaches. Let us consider each of these in turn.

1 Cutting the number of no shows

Firstly, front office staff ought to check guests’ stays and ‘chase’ any unconfirmed bookings, using letters, telephone or whatever other medium is appropriate. This is particularly important as far as groups are concerned, but it really applies to anyone. Secondly, the hotel should make sure that it has a clause in its standard booking contract specifying that rooms are only held until a specified time unless otherwise agreed. The time is usually somewhere between 6 p.m. and 7 p.m. This doesn't necessarily reduce the overall number of no shows, but it does allow the hotel to identify them in time to take some remedial action and thus reduce their impact.

2 Imposing financial penalties

As we saw when we looked at advance bookings, credit card bookings are ‘guaranteed’ (i.e. the hotel gets the room rate even if the guest is a no show). However, you still lose on meals and other extras. In any case, there are still guests who use other means of payment. In principle, a hotel can sue a no show for breach of contract if it has not been able to relet the room (after making a reasonable effort to do so, of course). This is often difficult because guests come from far away, and unproductive because the amounts are relatively small. Nevertheless, it is still worth sending a letter requesting compensation: even a few favourable responses will more than cover the postage costs, and it does tend to discourage future repetitions of the offence. A hotel can always ask for a non-returnable deposit. This is much more satisfactory, not because it covers the hotel's losses in the event of a no show (it is usually only a proportion of the final bill) but because it makes the potential no show think twice about booking at all. Another very similar practice is to include a provision entitling you to a cancellation fee as part of the booking contract, though there is no guarantee that you will actually get it. As we have said, some no shows take the form of early check-outs. Since the guest is repudiating (i.e. breaking) his contract, you can demand payment for the unused night in the same way as if he had failed to arrive at all, though you must also be prepared to refund it if you are subsequently able to relet.

3 Finding last minute replacement bookings

No shows tend to increase along with demand because smart guests know that last minute bookings can be difficult to make at peak periods and reserve accommodation on the off chance that they will want to use it. This means that you should be able to relet at such periods providing that you can ‘tap into’ the demand. One way of doing this is to have a wait list. You will probably continue to receive enquiries after you have filled your bookings chart. Try saying, ‘We're very sorry, we don't have any vacancies for that date at the moment, but if you will leave your telephone number we'll get back to you if we can’. You may not be able to do so, and even if you can the guest may well have found a room somewhere else, but calling back shows him that you are both efficient and courteous, which may lead him to contact you first in the future. In any case, you ought to be able to fill two or three rooms from a wait list of twenty or so names. Another method is to contact an organization which receives a lot of last minute enquiries. These include the airlines and commercial hotel booking agencies, together with the local tourist information office. One of the latter's roles is to put would-be guests in touch with local hotels, and it is likely to be receiving enquiries up until closing time (indeed, with modern computerized displays, it can still direct customers to you even after that).

4 Overbooking

This is the most important way of reducing the impact of no shows. In fact, it is SO important that it needs a section to itself.

Overbooking

Overbooking means deliberately accepting more bookings than you have room for. If you get it right, you should end up with just about the right number of guests, and your room revenue for that night will be close to the optimum. However, this raises the question of whether the practice is legal. The civil law position is quite clear: a hotel which fails to supply accommodation when it has undertaken to do so is guilty of breach of contract. We have already discussed your obligations in that respect. However, it is worth repeating that you must try to minimize your losses. A prudent hotelier who expected a certain number of no shows might well argue that overbooking was simply a way of doing this.

Criminal law is another matter. Telling a guest that he is booked when you are actually following a policy of overbooking may constitute a false trade description, and thus an offence under Section 14 of the Trades Descriptions Act. It can be argued that if you tell sixty-six customers that you are reserving rooms for them when in fact you only have sixty rooms, then you must be telling someone a lie. On the other hand, if you are reasonably sure that only sixty of those customers will actually turn up, then you are making the statement in good faith. The one is a false statement, the other a ‘fallible forecast’.

Unfortunately, this issue has not been resolved. The leading case is British Airways Board v Taylor (1975). In this case an airline ‘bumped’ a passenger, admitting that it had been overbooking and had got it wrong. The question of whether this was a criminal offence was taken all the way up to the House of Lords, but then had to be dismissed on technical grounds unconnected with the central issue. However, their Lordships did find that the justices were entitled to find as a fact that the airline's letter of confirmation was false within Section 14 of the Act. Even so, the general issue remains undecided. Unless or until it is clarified (possibly by someone else fighting a case through the Lords), we can't be sure. Our best guess is that double booking a specific room on a conventional chart almost certainly isn't legal, whereas overbooking using a density chart probably is (because you are not claiming to reserve a specific room). However, you need to be careful about overbooking limits. If you overbook to an extent which more or less guarantees that someone will be left without a room each night, then you may well be infringing Section 14, and you should keep this in mind while reading the following paragraphs.

Having done our best to clear up the legal position, let us consider the question of judicious overbooking using the figures in our earlier example. Clearly, you can't overbook the Fridays, Saturdays and Sundays since you are not fully booked for those nights anyway. However, you can do it for the Monday to Wednesday period, since you have almost certainly been turning bookings away (a 100 per cent occupancy rate usually reflects a much higher level of enquiries and actual requests). We will take Monday the 1st as a basis for our calculations. As our density chart shows, we actually took sixty bookings for that night. We probably had to turn away a number of later requests. Suppose we had accepted enough of those to compensate for the expected no shows? Let us compare what actually occurred with what might have happened:

| Actual | Possible | ||

| Bookings | 60 | 10% overbooked | 66 |

| No shows | 5 | No shows (10% of 66) | 7* |

| Arrivals | 55 | Arrivals (90% of 66) | 59* |

| Revenue (55 x £40) | £2200 | Revenue (59 x £40) | £2,360 |

| Revenue gain | £160 |

* We have rounded off these figures to whole numbers: you can't have 6.6 people failing to arrive!

Note that there is a built-in safety margin, since the number of no shows increases with the number of bookings taken and not the number of rooms. In this example, if you overbook by six, the number of no shows is more likely to be seven.

The case for overbooking is simply that it should bring actual receipts closer to the optimum room revenue (in this example £2,400). However, most reservation clerks contemplating it for the first time worry about what happens if they don't get it right and too many people turn up. So let us consider this, using the same example.

The actual no-show rate varies between 8 per cent and 12 per cent. If you overbook by 10 per cent (i.e. accept sixty-six bookings) and the worst happens (i.e. only 8 per cent fail to turn up), you would be faced with sixty-one arrivals (the figure is actually 60.7, but we've rounded that upwards for the reasons already explained). In fact, it is quite likely that you will be able to ‘stretch’ your accommodation in some way or other. There may well be a suite which you can convert in a hurry, or a staff room you can take over, or some other expedient. This is how many hotels record occupancies of over 100 per cent on occasion. However, let us look on the black side and assume that you CAN'T accommodate the extra guest. What can you do now?

The usual answer is to find a room for him somewhere else. This is called ‘booking out’ or ‘walking’. It may mean some frantic last minute telephoning, but an experienced clerk should have seen the crisis coming and made arrangements in plenty of time. Many hotels have reciprocal arrangements to cover exactly this kind of situation. Obviously, you will try to find a room in an equivalent hotel. If the alternative is much poorer than your own establishment, the guest is likely to feel aggrieved, and if it is much better, you will have to pay the difference in price.

This raises the important issue of just what you are liable for. Failure to provide the room you said you were going to is breach of contract, and you are liable to compensate the guest for any losses incurred as a result. These would include any additional travelling expenses or extra costs of the alternative room, but it doesn't generally cover compensation for disturbance or annoyance since these are very difficult to assess in financial terms.

With these points in mind, let us look at your problem again. What are you going to do with the guest you cannot accommodate? Fairly obviously, you are going to take him on one side, apologize profusely, tell him that you have arranged suitable accommodation elsewhere, offer to call and pay for a taxi to take him there, and give him a complimentary drink or so to help him pass the time while he is waiting for it.

Now, how much will all this cost? On balance, you are likely to lose a bit as far as the accommodation is concerned, because sometimes you will have to book the guest out into a more expensive room, which means you have to pay the difference, whereas if it costs the same as yours you neither gain nor lose, and if it is cheaper you can't claim the difference back from the guest (because you aren't supposed to profit from breaking your contract). However, you will only find yourself paying out in a minority of cases, and even then the differentials are likely to be fairly small. You might perhaps allow an average of £5 per guest for these payments.

What about the taxis and other expenses? The full retail rates might well be expensive, but then it's not the guest who is paying but you, and if you haven't already negotiated a contract on favourable terms with the taxi firm then you shouldn't be in business! In the same way, the drinks you offer are complimentary ones, and all you lose is their basic cost. Again, being generous, you might allow about £5 per guest, making £10 in all. The calculations now look like this:

| 10% overbooked | 66 | |

| No shows (8% of 66) | 5 (rounded off) | |

| Arrivals | 61 | |

| Roomed (@£40 per guest) | 60 yielding | £2,400 |

| Booked out (@£10 per guest) | 1 costing | £10 |

| Net receipts | £2,390 |

You will notice that this is £30 more than we achieved in our last example. In other words, overbooking pays, and overbooking close to the margin can pay even more, because booking out doesn't cost as much as you think.

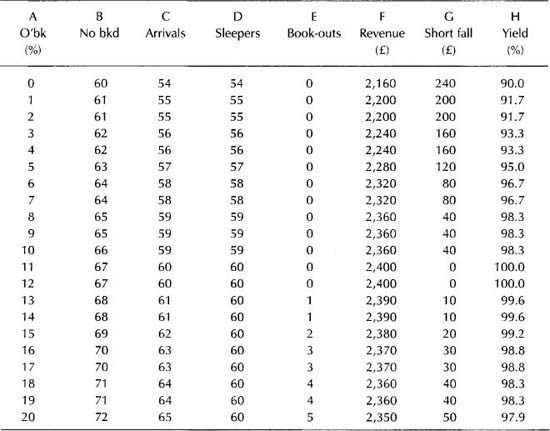

This kind of problem responds well to the use of a spreadsheet. Let us demonstrate this with the same figures that we used before (i.e. 60 beds @ £40 each giving an optimum revenue of £2,400, an average no-show rate of 10 per cent and a book-out cost of £10 per head) - see Figure 41.

Note: The formulae used are as follows (the actual format may vary somewhat from one spreadsheet to another):

| A (Overbooking %) | This is just the previous figure plus 1. |

| B (No. booked) | The formula is 60 + (60/100 x A). In simple English, this says that bookings are ‘the number of beds plus a number based on the overbooking percentage in column A’. |

| C (Arrivals @10% no show) | The formula is B - (B/100 x 10). In simple English, arrivals equal ‘the number of bookings (B) minus the no-show figure to be expected from that number of bookings (i.e. 10% of B)’. |

| D (Sleepers) | The formula is IF(C > 60,60,C). This is an example of an ‘if/then’ function. The structure is ‘if such and such is true, then x, if not, then y’. The commas in the sentence are in the same places as in the function. In simple English, it reads: ‘If arrivals (C) are greater than the number of beds (60), then sleepers equal the number of beds: if they are equal to or less than the number of beds, then sleepers equal arrivals’. This makes sense: you can sleep as many arrivals as you have beds for, but not more. |

| E (Book-outs) | The formula is IF(C > 60,C - 60,0). In simple English: ‘If arrivals (C) are greater than the number of beds (60), then book-outs equal the difference, if not, then they equal ‘0’ (i.e. there are no book-outs)’. |

| F (Revenue) | The formula is (D x 40) - (Ex 10). In simple English, revenue is ‘sleepers (D) times average rate (£40) less any book-outs (E) times the book-out cost (£10)’. This should be obvious. |

| G (Shortfall) | The formula is 2,400 - F. This is simple. In English, shortfall equals ‘optimum revenue minus actual revenue (F)’. |

| Yield % | The formula is F/2,400 x 100. It calculates actual revenue (F) as a percentage of optimum revenue. In this case we have rounded the result to one decimal place. |

Figure 41 Overbooking spreadsheet

Note that the yield figure rises with the level of overbooking until it reaches the optimum figure. In this example it is at its peak when you overbook by 13-14 per cent. Of course, this is true only for this particular set of figures, but the ‘optimum’ overbooking rate is generally higher than you would think. Yield falls thereafter as the overbooking percentage goes on rising because you are having to book more and more guests out.

The demonstration shows the value of using spreadsheets as a guide to management action, though you MUST remember that consistent overbooking to a point which guarantees that some guests will have to be ‘walked’ may constitute a Trades Descriptions Act offence.

A final point is that overbooking is not just a question of figures. It has an interpersonal aspect, too, because you are dealing with PEOPLE. What usually happens is that you start to be aware that there is a problem looming when you find your stock of unallocated rooms dwindling more rapidly than the outstanding names on your arrivals list. Eventually you realize that you are going to have to ‘walk’ one or two of the remainder. Three questions now present themselves. Which ones do you ‘walk’, what do you tell them, and who should do the telling?

The criteria for deciding who to ‘walk’ will vary from hotel to hotel. The fairest method would seem to be ‘first come, first served’, but this means that you may have to do it to favoured regulars or customers linked to important clients. Avoiding this can involve you in some difficult decisions, especially if there are only a couple of rooms left. The question of what to tell those you are booking out is even more difficult, especially since they may arrive before those to whom you have given preference. It certainly doesn't do your customer relations much good to tell a guest that he is going to be unlucky because you have overbooked and got it wrong! There are tales of hotels which have maintained an ‘Excuse of the Day’ book in order to avoid repeating the well worn ‘I'm sorry, we've had an accident with the central heating and your room is uninhabitable’ story. We will have to leave this to your own personal sense of ethics and (if appropriate) your imagination.

Who should do the telling? This is an unpleasant task, and one which is often shirked. Any receptionist ought to be able to handle it, but if you look at it from the customer's point of view you will realize that it is properly the responsibility of the reception manager or someone of equivalent status. After all, the hotel is letting the customer down, and it ought to show that it is treating the matter seriously.

Increasing average room rates

The second possible way of raising revenue is to get the guest to spend more. Since we are only concerned with room revenue here, we will not consider the way in which front office can help to promote the hotel's other services and facilities, though this is also an important part of the job. We will also ignore the most obvious way of increasing the average spend, namely, raising the tariff rates, since that is a marketing decision, and in this chapter we are only looking at what front office staff can do. You may feel that this doesn't leave very much, but you would be wrong. What you can do is sell.

Selling accommodation is much like selling any other product. There are a number of simple techniques which are taught on sales courses and which you should keep in mind. They are (in no particular order):

![]() Sell hospitality. This involves using the appropriate body language, including smiles. You have to make your customers like you, and the simplest way to do that is to show that you like them. It also includes lots of eye contact. This shows that you are interested in the other person and concerned for their welfare. Remember, too, that your body language can convey whether you are telling the truth or not. Open hands and a clear, steady gaze spell ‘trust’ in most cultures, whereas a sideways look and a nervous movement of the hand towards the mouth suggest duplicity.

Sell hospitality. This involves using the appropriate body language, including smiles. You have to make your customers like you, and the simplest way to do that is to show that you like them. It also includes lots of eye contact. This shows that you are interested in the other person and concerned for their welfare. Remember, too, that your body language can convey whether you are telling the truth or not. Open hands and a clear, steady gaze spell ‘trust’ in most cultures, whereas a sideways look and a nervous movement of the hand towards the mouth suggest duplicity.

![]() Use the guest's name. People respond well enough to ‘Sir’ or ‘Madam’, but these terms are rather impersonal. Addressing somebody by their name (e.g. ‘Mr Johnson’) still shows respect, but adds a touch of personal recognition as well. Whatever you do, DON'T refer to them by their room number (e.g. ‘Oi, you in 447’!).

Use the guest's name. People respond well enough to ‘Sir’ or ‘Madam’, but these terms are rather impersonal. Addressing somebody by their name (e.g. ‘Mr Johnson’) still shows respect, but adds a touch of personal recognition as well. Whatever you do, DON'T refer to them by their room number (e.g. ‘Oi, you in 447’!).

![]() Sell value. The main problem you face is that rooms are generally booked ‘sight unseen’: in other words, at a distance and some time before the accommodation is actually used. In these circumstances it is difficult to convince the would-be guest of the superior advantages of the higher priced rooms. It is much easier if he can see them side by side with the cheaper ones and compare their facilities. Outside hotels, a lot of selling is done in this way: you go into a store to buy something with a low price tag, then find yourself walking out with something much more expensive because the salesperson has taken the opportunity to show you a better quality product. So try to learn all about the facilities, and endeavour to find something extra to say about the more expensive types of room. Don't just say ‘We have some singles at £45...’ Try ‘We have some very comfortable singles at £45: they all have baths and toilets en suite and excellent views of the lake...’ You can always find something good to say about the facilities on offer.

Sell value. The main problem you face is that rooms are generally booked ‘sight unseen’: in other words, at a distance and some time before the accommodation is actually used. In these circumstances it is difficult to convince the would-be guest of the superior advantages of the higher priced rooms. It is much easier if he can see them side by side with the cheaper ones and compare their facilities. Outside hotels, a lot of selling is done in this way: you go into a store to buy something with a low price tag, then find yourself walking out with something much more expensive because the salesperson has taken the opportunity to show you a better quality product. So try to learn all about the facilities, and endeavour to find something extra to say about the more expensive types of room. Don't just say ‘We have some singles at £45...’ Try ‘We have some very comfortable singles at £45: they all have baths and toilets en suite and excellent views of the lake...’ You can always find something good to say about the facilities on offer.

![]() ‘Show’ the rooms. This is difficult but not impossible. In a small hotel you can literally take guests up to the rooms and show them the different facilities: you will often find that they will agree to take a more expensive room once they have seen that it really IS better. In a larger hotel this is more difficult, but you can still do a lot. Some hotels use photographs, while others rely on the receptionist's descriptive powers.

‘Show’ the rooms. This is difficult but not impossible. In a small hotel you can literally take guests up to the rooms and show them the different facilities: you will often find that they will agree to take a more expensive room once they have seen that it really IS better. In a larger hotel this is more difficult, but you can still do a lot. Some hotels use photographs, while others rely on the receptionist's descriptive powers.

![]() Use the ‘sandwich’. No, this isn't something sent up by room service, but a term used to describe the salesperson's technique of putting an unwelcome bit of news in between two ‘nice’ ones. In most cases the unwelcome news is the price. The ‘nice’ bits can be almost anything which makes the would-be guest feel better or gives him some justification for spending that amount of money. For instance, ‘Singles, sir? Yes (smile), we DO have a number of singles available. The larger ones are priced at £45, but they all have baths and toilet en suite and they also have excellent views of the lake...’ This approach starts with two or three positive touches (the ‘Sir’, the smile, the welcome news that you DO have some singles). It then goes on to the (presumably) unwelcome news that the rooms cost £45, but follows that up immediately with a number of reasons why.

Use the ‘sandwich’. No, this isn't something sent up by room service, but a term used to describe the salesperson's technique of putting an unwelcome bit of news in between two ‘nice’ ones. In most cases the unwelcome news is the price. The ‘nice’ bits can be almost anything which makes the would-be guest feel better or gives him some justification for spending that amount of money. For instance, ‘Singles, sir? Yes (smile), we DO have a number of singles available. The larger ones are priced at £45, but they all have baths and toilet en suite and they also have excellent views of the lake...’ This approach starts with two or three positive touches (the ‘Sir’, the smile, the welcome news that you DO have some singles). It then goes on to the (presumably) unwelcome news that the rooms cost £45, but follows that up immediately with a number of reasons why.

![]() Sell high. You might well have two classes of single, a cheaper one at £30 and a better one at £45. If someone rings up to ask the price, don't do as so many clerks do and say ‘We have some at £30 and some others at £45...’ That way, you are really telling the guest that he can enjoy all the public facilities of your hotel for £30. It is very difficult to persuade a customer to move upwards once you have indicated your lowest price, whereas it is fairly easy for you to come down. Launch into your spiel about the advantages of the dearer rooms. If your caller says something like ‘Well, I don't know...’ in a doubtful tone, you can always go on to add something like ‘Of course, we also have some slightly smaller rooms at £30 each. They don't have baths or toilets en suite, but they do have a shower cubicle and they're very comfortable...’

Sell high. You might well have two classes of single, a cheaper one at £30 and a better one at £45. If someone rings up to ask the price, don't do as so many clerks do and say ‘We have some at £30 and some others at £45...’ That way, you are really telling the guest that he can enjoy all the public facilities of your hotel for £30. It is very difficult to persuade a customer to move upwards once you have indicated your lowest price, whereas it is fairly easy for you to come down. Launch into your spiel about the advantages of the dearer rooms. If your caller says something like ‘Well, I don't know...’ in a doubtful tone, you can always go on to add something like ‘Of course, we also have some slightly smaller rooms at £30 each. They don't have baths or toilets en suite, but they do have a shower cubicle and they're very comfortable...’

![]() Assume that the prospective guest WANTS to stay at your hotel. It is possible to convert an enquiry into a booking by subtly ‘nudging’ a caller so that he moves from an uncommitted standpoint to one where he finds himself confirming a booking, almost without realizing that the decision has been taken, as in the following dialogue:

Assume that the prospective guest WANTS to stay at your hotel. It is possible to convert an enquiry into a booking by subtly ‘nudging’ a caller so that he moves from an uncommitted standpoint to one where he finds himself confirming a booking, almost without realizing that the decision has been taken, as in the following dialogue:

| Clerk: | Smoothline Hotel, Tracy speaking. How can I help you? |

| Caller: | I'm wondering if you have a single room for two nights, arriving next Tuesday? |

| Clerk: | I'll check, sir. What name is it, please? |

| Caller: | Mr Johnson. |

| Clerk: | Thank you, Mr Johnson. I won't be a moment. (Pause) Hello, Mr Johnson, yes, we DO have a room available. The rate is £45 and the room has a bath and toilet and an excellent view of the lake... Would that be acceptable? |

| Caller: | Er, yes. |

| Clerk: | What time would you be arriving, Mr Johnson? |

| Caller: | Er, about half past six I should think. Maybe a little later if 1 get held up on the motorway. |

| Clerk: | No problem, Mr Johnson. I'll put it down as a possible late arrival. Could you give me a telephone number, just in case? |

| Caller: | Well, my... my work number is (gives number) |

| Clerk: | Thank you, Mr Johnson. And your address? |

| Caller: | Er (gives address) |

| Clerk: | (Briskly) Thank you very much, Mr Johnson. That's a provisional single booking for Tuesday next, possibly arriving a little late. Can you confirm that for us before then? |

| Caller: | Well, yes, I suppose so. |

| Clerk: | Fine, Mr Johnson. We'll look forward to seeing you, then. |

Hopefully this shows how a vague enquiry can be ‘nudged’ gently but firmly into becoming a booking. The clerk starts with a relatively neutral question (‘What name is it, please?), then moves on from that (using the caller's name as often as possible) to describe the room (note the use of the ‘sandwich’ and how she ‘sells high’: if the caller sounds doubtful about the price she can quickly go on to mention the cheaper singles). These are followed by more loaded questions (‘Would that be acceptable?’ and ‘What time would you be arriving?’), carefully using the conditional tense at this point. As the caller commits himself by revealing more and more information, the clerk moves in to clinch the sale, briefly summarizing the details of the contract and making it clear that she expects the caller to go through with it.

At first sight these techniques may look like attempts to ‘con’ the customer out of his money. They are not. You are trying to draw his attention to the superior facilities on offer, and to persuade him that these are worth the extra money. If you genuinely believe this, then you will sound convincing, which is essential. In the end, the foundations of successful selling are simple:

![]() KNOW your product

KNOW your product

![]() BELIEVE in your product

BELIEVE in your product

Hard selling

Given suitable circumstances, it is possible to take a much harder line. As the well-known American hotel consultant C. De Witt Coffman wrote in 1974, ‘In almost any hotel it is possible to get the average daily room rate increased over what it was in the month just passed - without raising the posted rates’.

This sentence needs careful analysis. The reference to the average rate means that Coffman was not concerned so much with increasing the occupancy percentages as with actually persuading each guest to pay more. And this was to be done without raising the tariffs (i.e. the ‘posted rates’).

Coffman's approach provided an object lesson in terms of the management process. This involves planning, organizing, motivating and controlling. Let us see how Coffman's approach illustrated each of these stages.

1 Planning. Coffman began by establishing the hotel's average revenue. Then he proposed a target increase. In the example he quoted, this was to be slightly over 10 per cent. Remember that this was to be achieved within a month or two, and without any increases in tariffs.

2 Organizing. Coffman went on to find out how the hotel staff handled bookings. He or his assistants would pretend to make a number of these, using letters, telephone calls and visits and spreading these over the week so as to cover as many of the staff as possible. Some of the calls would purport to be from executives, others from special groups such as honeymooners or nervous old ladies. The staff performances were analysed under the following headings:

– Appearance (including voice)

– Courtesy

– Promptness

– Sales efficiency

Obviously, the ‘bookings’ would not come to anything, but this would not matter since they would be written off as ‘no shows’.

Having obtained a full picture of the hotel's practices, Coffman would visit the hotel and address a meeting of all the front office staff. There he would describe his ‘guest testing’ programme and outline his findings. This involved criticizing some of the things the reservations staff had been doing, but Coffman would never identify any individuals. Instead, he would take the opportunity to launch a training programme to set things right. The programme included a manual which covered many of the points we have already looked at, such as persuading doubles to occupy separate singles during slower periods, persuading singles to ‘double up’ in peak periods (perhaps not so easy in today's climate of opinion), using the ‘sandwich’ when quoting rates, and discouraging the indiscriminate offering of special rates.

However, the main technique he advocated went further. It involved some of the points we have looked at, but was based primarily on the idea of actually getting the guest into the lobby before the contract was finalized. Face-to-face selling is by far the most effective method and this becomes impossible if the contract is concluded at a distance. The technique was tailored to suit ‘same day’ bookings, and Coffman's reservations staff were trained to adopt a three-part strategy:

– On receipt of an enquiry they simply confirmed that there were rooms available and invited the traveller to come straight to the hotel, where they assured him he would be made very comfortable. On arrival, he was then allocated one of the higher priced rooms without any discussion about rates.

– If the would-be guest asked about rates (either over the phone or after arrival), Coffman's instructions were to ‘sell high’: in other words, to quote the highest feasible rate.

– If the would-be guest tried to negotiate a lower rate, Coffman's instructions were to avoid confirming this in advance. The manual contained a number of standard phraseologies, and the one suggested for this situation was, ‘We can't guarantee that rate, but we'll do our best to give it to you, or one close to it’. If the guest then turned up at the hotel, the receptionist was supposed to follow rule (a) and move him up at least one rate.

Obviously, these recommendations could not be followed in all cases, but their overall effect was to move a significant number of guests into somewhat more expensive rooms than they would have selected if allowed to choose for themselves.

3 Motivation. Coffman recognized that many reservations staff would be reluctant to practise this kind of ‘hard selling’ without some kind of incentive. He accepted that it was difficult to assess individual contributions to increased room rates targets, and suggested that the healthiest scheme was a central pool, with something like 10 per cent of the increase being divided up in proportions to be agreed by the staff themselves.

4 Control. The final part of the process was a series of follow-up ‘guest tests’, with refresher classes as necessary and a set of ‘reminder’ cards and posters displayed over a period of time.

Obviously, this approach would not be suitable for every type of hotel. We have quoted it here because it is still one of the best examples available of ‘hard selling’ taken to its logical conclusion, and because it gives us some idea of the limits of the possible. Remember that Coffman was a successful hotel consultant, and that he had actually put these ideas into practice. Remember, too, Coffman's contention that average room revenue could be increased by something like 10 per cent without increasing either occupancies OR room rates.

Assignments

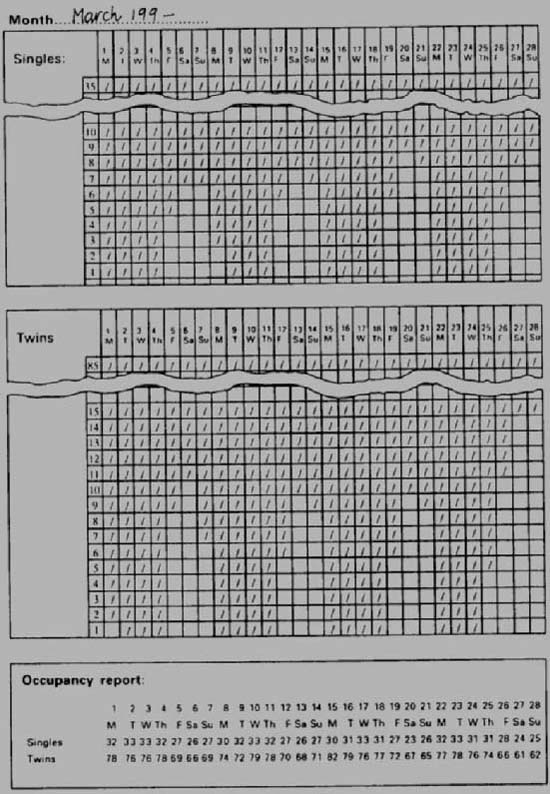

1 A hotel has thirty-five singles and eighty-five twins. The singles are priced at £38 each and the twins at £68. The preceding four-week period yielded the figures shown in the accompanying density chart and occupancy report (Figure 42), and you expect the booking pattern for the next period to be very similar. Calculate the optimum overbooking rate on the assumption that the average cost of booking out is £12 per person.

Figure 42 Density chart and occupancy report

2 The hotel is the same as in Assignment 1. Although one of the standard booking conditions is that room will only be held after 6.30 p.m. unless prior notice of late arrival is received, this provision is seldom enforced. On Day Two of the following period (a Tuesday) you have taken thirty-eight single bookings. Of these, thirty-three have checked in and registered by 7.30 p.m. and you are left with the following outstanding names on your arrivals list:

| Name | Stay | Confirmed | Comments |

| Armstrong C Mr | 1 night | Yes | Regular. Usually arrives by car by 6.00 p.m. or earlier. No explanation for delay. |

| Jones LS Mr | 3 nights | Yes | Not known. Three-month-old booking reconfirmed last week, but no note about late arrival. |

| Tibbs S Miss | 1 night | Yes | Booked through travel agent: known to be elderly, disabled and likely to arrive late. |

| Schmidt J Herr | 2 nights | Yes | German, booked through regular account customer (a large local company). No note re late arrival, but flights known to be delayed. |

| Palfrey S Mr | 1 night | No | Booked two weeks ago, request for confirmation ignored. Claims to know your company's chairman. No note of late arrival. |

You have an arrangement with a nearby hotel, and you have already confirmed that they can take two or three extra guests. You also have one ‘chance’ customer in the lobby, a Mr Atkins, who wants to stay for three nights. He is respectably dressed, carries appropriate luggage and appears able and willing to pay. What should you do?

Note: There is no reason why you shouldn't run this like the role playing exercises in the previous chapter. Appoint one person as receptionist, and another as front office manager. Let them confer. Then allocate the ‘customer’ roles to other members of the group, and let them enter one by one in random order.)

3 You are a receptionist at the Takem Inn, operating on Coffman's principles. You have three classes of singles available, respectively £75, £60 and £45 each. You are required to respond to the following callers, all of whom are using your courtesy phone at the local airport and who need accommodation for tonight. There is little spare accommodation elsewhere:

| Caller A: | Should be timorous, reluctant to make a fuss and rather nervous about the prospect of not being able to obtain accommodation at all. |

| Caller B: | This caller will try to establish the room price, but should be fairly easygoing and not too hard to influence. It may help to think of him as being able to charge the cost against expenses. |

| Caller C: | A competitive and aggressive character, keenly interested in limiting his expenses. |

(Note; This should be conducted on a role play basis in conformity with the suggestions outlined earlier. The roles should be switched around and the ‘calls’ taken in random order.)

4 Discuss front office's role in increasing the hotel's overall sales (i.e. food and beverage and other receipts as well as room revenue).

5 Outline a possible incentive scheme for front office staff which might be introduced by either the Tudor or Pancontinental Hotel.