Chapter 4

Legal aspects and security

Introduction

We make no apology for starting this section with a chapter devoted to these two closely related topics, since both involve people.

Hotels have been subject to legal control ever since the Middle Ages. Travellers were vulnerable, and villainous innkeepers were sometimes tempted to charge them extortionate prices, or even to rob them while they slept. Even today, hotels are not allowed to pick and choose their guests, and those classed as inns have a legal obligation to look after their property while they are staying. You need to understand these rules.

Not all guests are honest, either, and the hotel must protect its other guests and itself against the occasional dubious customer. This may involve taking some form of legally sanctioned action to exclude him, to obtain payment from him, or to prosecute him. You need to know what your powers are in these matters, too.

There are two kinds of threat that you need to be concerned about:

1 Anything that might affect a guest's health, comfort or well-being. This must be given priority. The hotel exists to provide a service for its guests, and if it starts to put its own interests or convenience first it will quickly go out of business.

2 Anything that may affect the hotel, in particular, its fixtures and fittings, its revenues or its reputation.

There is also a third major area, that of possible risks to the hotel's staff. However, this ‘health and safety at work’ aspect falls outside the scope of this book and we simply note it here for the record.

Legal aspects

You should consult a specialist law textbook for the full particulars, but you should be familiar with the following:

1 Contracts for accommodation. When a hotel accepts a booking from a guest, it enters into a binding contract. The guest is expected to turn up, and the hotel must provide the agreed accommodation. If either party fails to honour its side of the bargain, it must compensate the other for any loss suffered. However, the guest is also expected to behave reasonably, and if he turns up in a drunken or verminous state, or behaves in a violent, quarrelsome or otherwise unsuitable fashion, he may be deemed to have broken the contract and the hotel may require him to leave. Exactly what kind of dress or behaviour would constitute breach of contract is a matter for the courts.

2 The Hotel Proprietors Act 1956. Under this, a hotel defined as an ‘inn’ (which means most of them) has an obligation to accept bona fide travellers who ‘appear able and willing to pay a reasonable sum for the services and facilities provided, and who are in a fit state to be received’. This last excludes would-be guests in the kind of states we have described above. The hotel may put a guest on its black list if it has previously had an unfavourable experience with him, but the question of whether it can do so on the basis of some other hotel's report does not seem to have been tested.

3 The Sex Discrimination Act 1975. This prohibits a hotel from discriminating against women as far as the provision of goods, facilities or services are concerned.

4 The Race Relations Act 1976. This prohibits a hotel from discriminating against any person on the grounds of colour, nationality, race or ethnic origin, again as far as the provision of goods, facilities or services are concerned.

5 Payment in advance. Nothing in the above provisions prevents the hotel from demanding payment in advance. This is one of your main lines of defence against dubious customers, so long as you do not use it as a concealed form of discrimination. You may also request interim payments at any time.

6 Trespass. Normally, a property owner can stop anyone else from coming onto his property without permission. The intruder is a ‘trespasser’ and can be required to leave. He can also be sued if he causes any damage, though he cannot be prosecuted since trespass is a civil law matter. The obligation to accept bona fide travellers imposed by the Hotel Proprietors Act limits this right as far as hotel operators are concerned, but it certainly does not give travellers the right to wander all over the hotel. One who has merely called in for refreshment is entitled to enter public rooms such as the bar or restaurant, but not the accommodation block, and even a guest who is staying the night has no right to explore corridors other than his own. No guest has any right to enter areas which are clearly marked ‘Staff’. These limitations are important because they allow hotel staff to challenge suspicious characters, though of course this should always be done tactfully (‘May I help you? Which room are you looking for?’).

7 The right of lien. This old common law right was codified in the Innkeepers Act of 1878. It allows a hotel to seize a guest's belongings and sell them to defray its costs if his bill is not paid. However, it is hedged around with a number of restrictions, and in any case the professional swindler normally takes care not to bring much that is worth seizing.

8 The Theft Acts. Section 1 of the Theft Act 1968 defines theft as follows:

‘A person is guilty of theft if he dishonestly appropriates property belonging to another with the intention of permanently depriving the other of it.’

It goes on to add:

‘A person is guilty of burglary if he enters any building’.... as a trespasser and with intent to commit any such offence ...

These provisions cover the thief who enters hotel premises in order to steal property belonging either to the hotel or its guests, but the position regarding the person who simply left a hotel or restaurant without paying remained obscure until the Theft Act of 1978, which added:

‘Any person who by any deception dishonestly obtains services from another shall be guilty of an offence’

and:

‘Any person who, knowing that payment on the spot for any goods supplied or services done is required or expected from him, dishonestly makes off without paying as required and with intent to avoid payment shall be guilty of an offence.’

As with all serious criminal offences, you have to prove not only that the defendant did what you allege (e.g. stayed the night and then made off without paying), but also that he did so ‘with intent’. The difficulties this can cause are illustrated by R. v Allen (1985). In this case, the defendant did indeed stay at a hotel and then left without paying his bill. He came back later to collect his belongings, saying that he intended to pay as soon as he received the proceeds from certain outstanding business transactions. He was arrested and convicted under the Theft Act 1978, but the Court of Appeal quashed the conviction and the House of Lords upheld its decision on the grounds that intent to avoid payment required an intention to do so permanently, and not merely one to delay or defer it. Serious criminal charges must be proved ‘beyond all reasonable doubt’, and R. v Allen shows how difficult this can be.

9 Right of arrest. According to the Criminal Law Act 1967, any citizen may arrest without warrant anyone who has committed, is committing, or who he has reasonable cause to suspect of committing or having committed an arrestable offence. However, such action is dangerous, legally speaking, because the guest might sue you for one of a number of torts. Stopping him without good cause may amount to false arrest, and detaining him against his will to wrongful imprisonment, while grabbing his suitcases without his consent may constitute conversion. Threatening him is likely to be assault, while holding him back by force could be battery as well. Finally, wrongly accusing him in the presence of witnesses could well amount to slander. You would be well advised not to commit yourself to any of these actions unless you are absolutely sure of your facts.

Other legal implications are best looked at as part of security, so let us go on to that.

Protecting the guest

There are a number of possible threats to a guest's comfort and well-being, but the most serious is any threat to his physical safety.

Threats to the guest's life or limb can arise from internal or external sources. The melancholy fact is that more guests are injured as a result of a hotel's carelessness than as a result of the action of external agencies. Since we hold that security is everybody's business, we ought to consider this first.

Internal threats to the guest's person

The major risk is fire. This puts everyone in the hotel at risk, not just the careless individual who may have started the blaze in the first place. The real hazard, as you should know, is not the fire itself but the smoke and fumes, which generally suffocate victims long before the flames actually reach them.

The chief responsibility for ensuring that fire risks are adequately guarded against belongs to management as a whole, acting on the specialist advice of the local fire officers, who are empowered to issue a fire certificate provided that their requirements are met.

However, occasional fire inspections can be undermined by slack or inefficient working practices. Since we believe that all front office staff have a responsibility to protect the guests in their charge, we maintain that you ought to satisfy yourself with regard to the following key areas:

1 Fire detection systems. A high proportion of hotel fires begin at night, when most guests and staff are asleep. It is essential that the hotel should be protected by appropriate detectors (smoke, heat or flame, depending on location) and that these be properly maintained and tested regularly.

2 Fire containment provisions. A good deal of time and money has been spent on the installation of fire doors and adequate fire escape facilities, but all too often these are not maintained as they should be. Doors are left propped open, windows are allowed to become unopenable. Such practices are not in the guests’ long-term interests.

3 Escape procedures. Clear and unambiguous instructions must be displayed in every room so that guests know which way to go in the event of an emergency.

4 Fire-fighting equipment. Hotels should be properly equipped with fire extinguishers. These must be serviced regularly, and staff trained in their use.

If you aren't satisfied with respect to all or any of these, then say so, tactfully but firmly. After all, you don't want to work in a death trap.

There are plenty of other possible hazards to guests, such as worn carpets, slippery tiles, insecure handrails, faulty electrical wiring or unreliable lifts. Your management will be aware of the dangers involved should the guest be able to prove negligence or breach of occupier's liability, but it may still need to have specific threats brought to its notice. If a guest says on checking out, ‘Oh, by the way, you ought to get that electric kettle in my room seen to: I got a slight shock when I plugged it in...’, then get it checked out: the next occupant may not be so lucky.

Terrorist threats

Hotels which cater for VIPs need to take bomb threats and other forms of terrorism very seriously indeed.

Such hotels will normally liaise closely with their local police forces, who will advise them regarding security precautions and take over whenever visitors particularly at risk are staying. The most dramatic threat is that of some kind of assassination attempt: fortunately, this is very unlikely and even if it did happen nobody would expect front office staff to ‘have a go’ or do anything other than take cover.

The police will expect co-operation in other respects, however. Hotels are by their very nature vulnerable to the infiltration of terrorists masquerading as innocent guests. In particular, staff would be expected to keep their eyes open and to report anything suspicious, from a visitor who does not seem to ‘fit’ to an unattended piece of luggage.

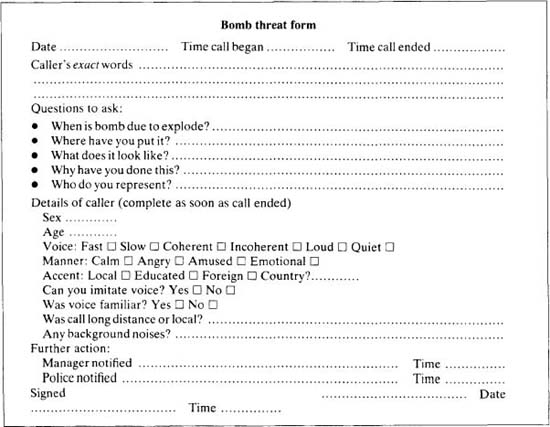

In other respects, front office staff are likely to remain ‘in the front line’, and need to conduct themselves accordingly. The chief threat is the telephoned bomb warning. The vast majority of these are likely to be hoaxes, but they cannot be taken lightly. Staff liable to take such calls (usually one of the switchboard operators) need to be trained to handle them correctly. There are two essential requirements:

1 The caller should not be interrupted, and his words must be written down exactly.

2 As soon as he is finished, you should write down as many details as you can remember about the caller's voice, mannerisms, etc. It is essential to do this as quickly as possible because it is then that the facts are freshest in your mind. Bear in mind that there is an almost irresistible temptation to ‘decorate’ the facts with each retelling.

It is a good idea to have a standard form such as the one shown in Figure 36 ready to hand for this purpose.

Another related threat arises from letter bombs. Again, the police will normally advise you on these, but it is not always possible to foresee exactly where and when a deranged terrorist may decide to strike.

Staff responsible for dealing with mail should be given some instruction in the recognition and handling of suspect packages. As a general rule, such packages are safe enough as long as they are not opened, but this may not apply If they arrive in a damaged state. Moreover, there is a slight but genuine risk that the detonator might be affected by radio transmissions, so all packages should be kept separate from any radio paging equipment being operated by the hotel.

Threats to privacy

Again, this is most likely to be a problem as far as VIPs are concerned. The activities of the famous make good ‘copy’, and there are always reporters who are on the lookout for spicy stories. They may try to get you to give them information by using flattery or even a little low-level bribery. You should resist being used in this way.

Famous guests might also be pestered by fans and autograph hunters. It is part of your job to prevent this from happening.

There is yet another way in which you might breach your duty of confidentiality. Let us suppose that an earring is found in a room after a couple have left. The room attendant reports it to the housekeeper, who tells you. Wishing to be helpful, you check the couple's home telephone number on the registration form and ring them up. A woman's voice answers. ‘Hello, Mrs Smith,’ you say. ‘I'm sure you'll be pleased to hear that we've found your earring.’ ‘What earring?’ she asks, clearly puzzled. ‘The one you left at our hotel,’ you reply. ‘What hotel?’ she asks. The one you've just been staying at with Mr Smith...,’ you answer. Only then does it become clear that whoever Mr Smith had been staying with, it wasn't the lady you are now talking to...

In this instance you may be inclined to argue that ‘Mr Smith’ deserves all he is likely to get, but that is none of your business. A guest is entitled to privacy, whoever he or she is, and you should regard confidentiality as a major duty.

Threats to guests’ property

Hotel guests often carry considerable amounts of money or other valuables with them, and this makes them targets for a variety of unscrupulous characters. The threat comes from a variety of sources:

1 Muggers. A hotel room offers a quiet and secure location for an assault if the criminal can get the unsuspecting guest to open the door. Hotels do not offer easy getaway routes, but this is only a problem if the assailant leaves the victim able to raise the alarm afterwards. Fortunately, few British criminals are quite as ruthless as this, but hotel muggings have become a serious problem in some particularly violent urban areas in other countries.

2 Sneak thieves. Large and busy hotels offer happy hunting grounds for certain kinds of professional thieves. Pickpockets and bag snatchers might work the bars, lobby or pool. There are also well-dressed, confident looking room thieves who wander around the corridors undisturbed, testing bedroom doors to see whether they have been securely locked, or trying out their armoury of keys. Should they find themselves faced with a genuine guest they can always apologize and withdraw: mistakes over rooms are easy enough to make, after all. Obviously, it is even better from the thief's point of view if he IS a genuine guest, because then he has a perfect right to walk around the hotel. Some thieves do check in as legitimate guests: their aim is to steal enough to cover their expenses.

3 Confidence tricksters. Expensive hotels offer the perfect environment for such persons. Their guests are generally well off, and often surprisingly gullible. Confidence tricksters book in as legitimate guests and then move in on likely looking targets. Their ‘scams’ vary, but are almost always based on character weaknesses on the part of the ‘marks’, or victims. The result is that the victim is often too embarrassed to complain afterwards, which makes prevention particularly difficult. Confidence tricksters generally pay their bills in a perfectly normal manner (from their point of view, these are legitimate business expenses).

4 Prostitutes. These present hotels with the same problem as confidence tricksters in that guests seldom complain if they end up on the losing side. Prevention is made even harder by the fact that the guest will deliberately conspire to smuggle the prostitute into his room, evading whatever security routines you may have introduced to prevent this from happening. Although prostitution itself is not illegal, prostitutes tend to live in a shadowy borderland between the legal and the illegal, and may well take advantage of the opportunity offered when they are alone in a room with a guest who has just dropped off to sleep, carelessly leaving his wallet in full view. Some years ago the Metropolitan Police felt justified in launching a campaign based on the slogan ‘Prostitutes Are Thieves’. There are other reasons why hotels should do everything they can to discourage prostitution, and we will look at them later.

For the sake of completeness, we ought to note two further possible sources of risk:

1 Staff. The contrast between staff and guest incomes is often marked, and guests are not always either very tactful or very careful. It can be very tempting to come across a bulging wallet lying on a dressing table, especially when the guest's behaviour leads you to suspect that he does not know exactly how much was in it when he put it there. There are far fewer staff thefts than one might suppose, but they do happen.

2 The guests themselves. Some guests are tempted to level accusations against the hotel when it is really their own carelessness that is the cause of the loss. Others may do so rather than admit to having lost the money in some more embarrassing way, such as gambling or to a prostitute. Finally, there are a few wholly dishonest guests who will deliberately claim to have lost something they never had in the first place, hoping that the hotel will agree to compensate them rather than mount an embarrassing investigation.

Clearly, all these threats should be avoided as far as possible. There are several lines of defence:

1 The hotel must do its best to ensure that casual undesirables such as thieves and prostitutes do not obtain access to public areas such as bars. A hotel is private property and you have every right to require trespassers to leave.

2 Deterring known con men and ‘gentleman thieves’ is mainly a matter of putting them on your black list and then refusing to allow them to make a booking. Hotels can and do exchange information about such individuals.

3 Installing discreet surveillance equipment in the public areas could reduce casual theft. This is not so common as in department stores because there is not the same amount of pilferable stock on display, but it might be necessary in crowded areas where pickpockets could otherwise work with impunity (such as a casino).

4 Guests’ rooms must be made as secure as possible. Wide angle viewing lenses can be built into bedroom doors, and stout door chains provided at relatively little cost. If mugging is a serious risk, guests may have to be warned not to open their doors unless they are sure who is outside. This might sound alarmist, but it is better to be safe than sorry. In fact, muggings are much more likely to take place outside the hotel. The guest may be unfamiliar with the immediate environment, and may have to be warned if he proposes to go out late at night on foot. This ought to be as much a part of your job as key control. The whole question of locks and key control has been revolutionized over the past two decades or so. The old metal key has now been largely superseded by the new electronic keys which:

– Allows front office to change the combination every time a room is relet or the guest loses his key.

– Allows selective room access. Maintenance staff, for instance, can be given keys which allow access to a specified room or group of rooms only.

– Produces a record of all room entries, showing both the exact time of entry and the type of key used (guest, room staff, maintenance, management, etc.).

5 The disadvantage of these electronic systems is that they tend to be relatively expensive, though the cost can be offset by lower running expenses such as insurance premiums and lock replacements. A compromise approach developed in the USA allows for removable ‘lock cores’ which can be replaced quickly and then reprogrammed and used elsewhere.

6 Guests’ property must be safeguarded. We have already mentioned the hotel's obligation to accept valuables for safe keeping, and looked at the routines involved. However, depositing cash and jewellery can be inconvenient, and many guests prefer to use a room safe. There are a variety of different products available, ranging from permanently installed safes down to a portable safe box which can be rented out from front office and attached to one of the fixtures in the room. They do not provide the same amount of security as a wall safe, but they are usually sufficient to deter the casual sneak thief. The question of whether the provision of a room safe affects a hotel keeper's legal liability is an interesting one which does not yet seem to have come before the courts. Normally, if a guest elects to leave valuables in his room, he is deemed to have accepted the risk involved, and thus bears the responsibility for any consequent loss unless the hotel can be shown to have been negligent. It might be argued that if the hotel provides a room safe it is, by implication, offering an alternative to its ‘deposit for safe keeping’ obligation, and should thus be liable in full should the safe prove to be insecure. However, there is an important difference in that the front office safe is (or should be) under constant guard, whereas the room safe is bound to be unwatched for considerable periods (i.e. while the guest is out of the room). Consequently, we do not believe that such safes affect the general legal position regarding the hotel keeper's liability. The hotelier is still obliged to accept valuable articles for safe keeping, and remains fully liable for them. Should a guest decide to entrust such articles to a safe in his room, that remains his decision, and he must accept responsibility.

Other threats to the guest's enjoyment

The main problem is likely to be drunken, quarrelsome or noisy behaviour on the part of other guests. This has probably ruined more holidays than fire or theft ever did.

If a traveller turns up in a drunken state and asks for a room, you are entitled to refuse him on the grounds that he is not in a fit state to be received. This is true even if he already has a booking, because he has broken one of the implied conditions of the contract.

The same applies to a guest who misbehaves during his stay. The fact that he was fit to be received when he arrived does not mean that the hotel is obliged to let him stay if he subsequently behaves differently.

Drunken guests are a threat to your possession of a liquor licence, because permitting drunkenness is grounds for removal of that licence. You must therefore take steps to persuade them to leave the bar and go to their rooms.

Normally, what they do there is their own business, as long as they do not damage your property or inconvenience any other guests. If they persist in behaving in a noisy and boisterous fashion, then someone will have to go up and try to quieten them down. In the last resort, they can be asked to leave.

Obviously, this process requires considerable tact, but then so does dealing with complaints from your other guests. Always remember that if a guest rings down to reception to complain about being kept awake, that guest has probably spent a sleepless hour or so working himself up to do it. Most people don't really like to complain (there are always exceptions, of course), so if you get two or three such calls it is definitely time for action!

Protecting the hotel

Threats to the hotel's property

Your furnishings are bound to suffer some wear and tear, and it is unreasonable to hold guests to account for normal domestic accidents such as broken glasses or spilled coffee. However, items smashed as a result of drunken horseplay are a different matter. A hotel is entitled to expect that its guests will behave at least as carefully as they do at home, and there is thus an implied condition in the contract that they will compensate the hotel for any loss or damage if they don't. In such circumstances the hotel can add a reasonable amount to the guest's bill to cover the costs. Whether it does so or not is a question of policy, and would probably depend on the seriousness of the damage.

The real security problem, however, lies with guests who steal things. As any hotelier will confirm, virtually anything can vanish from a hotel bedroom. Motels are particularly vulnerable, because their guests park their cars conveniently close to the accommodation and commonly pay in advance so that they can make an early (and unobserved) departure. There are stories of couples who have arrived in a van or station wagon and then spent the night removing every fixture and fitting in sight with a view to installing them in their own homes.

The only answer lies in having housekeeping staff inspect the room as quickly as possible, and preferably before the guest checks out. This is much easier to recommend than to organize. However, let us assume that the housekeeper has checked the room and that you have just received a report that certain items are missing. What do you do now?

As we have seen, a direct challenge may have awkward legal consequences. However, a more tactful approach sometimes works. You might ask the guest to step to one side and then say, very politely, ‘I'm sorry to bother you, but the room attendant says she can't find all the towels. Guests occasionally pack one or two hotel items when they're in a hurry, quite accidentally of course. I wonder if you mind very much just checking before you leave?’ At which point the guest usually says, ‘No, of course not’, opens his suitcase, turning slightly pink as he does so, and lo! there are your towels. If instead he elects to brazen it out, saying something like ‘I'm in too much of a hurry to check now. If I do find anything, I'll return it, of course...’, then you are probably best advised to accept his statement and write off the items.

Expensive items of equipment can be protected to some extent by fixing them to the furniture or walls. Another useful idea is security marking: a permanent and visible mark will make it more difficult to sell the item and more embarrassing to use it at home, while ‘invisible’ marking is helpful in tracing stolen items. Nowadays such items can also be linked to a computerized alarm system.

Remember that not all such thefts are committed by guests. One of the thief's simplest and most effective methods is to don a pair of overalls and walk into a busy establishment with a nonchalant air, trusting (generally correctly) that anyone who sees him will assume that he has a legitimate reason for being there. Many a piece of equipment has been brazenly removed under the eyes of a dozen or so staff.

‘Walk-outs’, ‘skippers’ or ‘runners’

These are guests who leave without paying. They can be divided into three groups:

1 The ‘accidentals’, or guests who simply forget to pay. They may be confused over who was due to settle the account, or may genuinely forget an ‘extras’ bill. Forgetfulness is a real possibility, so you should always be tactful when contacting a walk-out. Genuine ‘accidentals’ will normally be highly embarrassed and pay up immediately.

2 The ‘opportunists’. These are people who had every intention of paying their bills when they first checked in, but who subsequently realized that they could get away without doing so. Hotels whose design allows guests to reach the car park without passing reception have found a number of their guests yielding to this kind of temptation. Opportunists also take advantage of weaknesses in the hotel's billing procedures. In the days before POS (point of sale) computer terminals became common, cashiers often had to ask a guest whether he had consumed breakfast. A surprising number said ‘No’ and left before their breakfast voucher could come through. This is still likely to be a problem in a non-computerized hotel. Guests also tend to ‘forget’ to declare mini-bar consumption.

3 The ‘premeditators’. These are people who never have any intention of paying in the first place, and who sometimes go to considerable lengths in order to avoid doing so. ‘Premeditators’ often repeat the same offence at hotel after hotel around the country. This underlines the need for some kind of information exchange.

‘Premeditated skipping’ is an odd crime in as much as the perpetrator is seldom destitute. He cannot guarantee that he will not be stopped and made to pay, and yet he obtains no permanent benefit from his crime if he gets away with it. In other words, his motivation is often a kind of cheeky desire to put one over on the establishment.

This helps to explain why experienced hotel staff claim that they have a ‘nose’ for walkouts. There are various subtle indicators which help them to ‘smell a wrong ‘un’. They include an absence of luggage and a lack of corroborative evidence of identity. Evident nervousness and a reluctance to provide registration particulars may betray the inexperienced ‘first timer’ planning a walk-out, while a high degree of self-confidence and a very plausible but hard-to-check explanation to account for his missing luggage is likely to mark the practised ‘skipper’. As one security officer said, ‘It's the little inconsistencies I look for, especially between the things he can get on credit and the things he can't, like an expensive suit coupled with a cheap haircut’.

Housekeeping staff can check whether the guest has unpacked very many personal belongings: a minimum of toilet articles and a locked suitcase are strong grounds for suspicion. In a well-run hotel the first department to have its suspicions aroused will communicate these to all the others, and the establishment will begin to operate like a top-class intelligence-gathering machine, with the doubtful guest being reported on wherever he goes, while the security department tries to establish his bona fides.

Walk-outs do not really cost the hotel very much (you may not have been able to let that room to anyone else anyway, and the cost of the food and drink consumed is much lower than the selling price), but they are annoying, and you should be on your guard against them. The biggest problem you face is that the ‘professional walk-out’ is usually very plausible. In addition, he will generally pick on the most inexperienced looking member of staff available, and choose the busiest time of the day to make his approach.

Hotels use or have used a number of security measures to reduce the incidence of ‘walk-outs’:

1 Credit status checks. It may be possible to confirm a guest's credit status from his registration particulars by checking with a commercial credit agency. This is the job of the security officer, but he needs the co-operation of the receptionists, who should refer ANY ‘chance’ or otherwise doubtful customers to him for clearance.

2 Payment in advance. As we have seen, a hotel is entitled to demand this, and receptionists should always do so if they have any doubts about the guest's reliability. It should be normal practice in the case of a chance guest, for example.

3 Interim payments. An alternative approach is to establish a credit limit, and to ask for an interim payment or additional credit card authorization as soon as the guest's account reaches it. Computerized billing programs allow you to enter this limit, and will ‘flag’ the account as soon as it is reached. This practice prevents the guest from running up a very large bill. The process of approaching the guest and asking for the interim payment requires considerable tact, but most customers do understand the problems caused by the dishonest minority and co-operate willingly enough, especially if it is explained to them as ‘hotel policy’.

4 ‘Guaranteed’ bookings. As we have seen, if a would-be guest has given a credit card number at the time of booking, and does not then cancel the booking within a reasonable time, the hotel can make out a credit card voucher in the usual way and the company will pay it and debit the guest's account. This is obviously a considerable improvement from the hotel's point of view, and helps to explain why credit card bookings are preferred to cash ones.

5 Luggage passes. These used to be common in the days when guests travelled with large amounts of baggage. This was taken down to a luggage room on the day of departure and not released until the cashier issued a luggage pass confirming that the bill had been paid. Air travel has made these obsolete.

6 Lien. As we have seen, this is the right to retain possession of a guest's luggage until he has paid his bill.

Cash frauds

Guests sometimes practise various kinds of sleight of hand while ostensibly paying their bills.

1 Credit card or travellers’ cheque fraud. Lost or stolen cards or cheques are often presented as ‘payment’. Cashiers should follow the normal security checks.

2 ‘Confusion cash’ frauds are practised quite frequently in some major centres. In these, the fraudster offers a variety of notes of different denominations, then changes his mind, offers a different combination, and ends up by so confusing the cashier that she hands over more money in change than the fraudster started with. Set down in black and white this practice sounds unlikely, but some people are very clever at such tricks.

3 Foreign currency frauds are also quite common. The fraudster may obtain some out-of-date foreign notes (countries sometimes call in their old currency and replace it with new notes) and pass these off on an unsuspecting cashier in a small hotel. Alternatively, they may offer a little-known currency with a lower value than its better-known cousin (for years, the Eastern Caribbean dollar was worth half the American one, and the Icelandic krona an eighth of the Swedish). The answer is to equip cashiers with a display showing all the current foreign currency notes accepted by the hotel.

Bad debts

Bad debts are not the same as ‘walk-outs’. A bad debt is a bill which the hotel has transferred to the ledger in good faith, but which does not get paid for one reason or another.

One possible source of bad debts is the ‘guaranteed’ booking. Sometimes companies or travel agencies handling large volumes of business make arrangements whereby rooms will be kept beyond the normal check-in time, and that bills will be honoured even if the guest does not turn up. This type of arrangement is a fruitful source of misunderstanding. The guest involved may dispute the bill, saying, ‘I telephoned and cancelled the booking in plenty of time’, or ‘I arrived late and was told they were full so I had to go elsewhere...’ Hotels are often reluctant to press the guaranteeing company for payment because they represent important sources of business.

One of the main sources of bad debts, however, is the company in difficulties. One of the standard responses to a cash flow crisis is to slow down payments. The money available will tend to go to wages and to major trade creditors, and hotels come pretty far down the list. Again, hotels are often reluctant to press companies with whom they may have been doing good business for years.

Responsibility for controlling bad debts rests on the accountant, who must keep a wary eye on the current financial situation of the hotel's major clients. However, front office staff can find themselves in the front line when they have to explain to a well-liked regular that they can't take his booking unless he pays cash.

If a company fails to pay an account, the services of a commercial debt-collecting agency may be called upon. This costs money and the hotel may adopt a policy of writing off amounts below a certain figure.

Immorality

This is a serious issue. As we indicated in our Introduction, guests who find themselves removed from the constraints of their home environments sometimes turn to call girls or rent boys for consolation. Similarly, business travellers have been known to take temporary companions along with them on their trips, and hotels sometimes find themselves acting as houses of assignation where lovers can meet in comparative secrecy.

Immorality as such is not unlawful. Nevertheless, a hotel is well advised to restrict its incidence as far as possible, for a number of reasons:

1 As far as civil law is concerned, it may affect the validity of the contract for accommodation. Certain ‘contracts’ are held to be void because they are contrary to public policy. These include ones involving sexual immorality (see Pearce v Brookes (1866)). This rule might apply if you knowingly let a double room to an unmarried couple. In such circumstances, you would not be able to sue them if they left without paying. Whether or not ordinary cohabitation implies immorality in these days of live-in partners is open to question, but the risk was still serious enough in the 1980s to cause many hotels to prefer not to let double rooms to unmarried couples. If a couple were to register as ‘Mr and Mrs’ you would normally have no reason to suppose that they were not married, and the contract would thus not be void (unless you knew one partner to be a prostitute who made a practice of masquerading as the ‘wife’ of a variety of partners).

2 Although prostitution itself is not illegal, English criminal law penalizes any third party who tries to profit from it. Living off immoral earnings and being concerned in the ownership or management of a brothel are both serious offences. It is possible that the management of a hotel which could be shown to have regularly let rooms to known prostitutes might be prosecuted for one or other of these offences. However, prosecutions of this kind seem to be very rare, presumably because the police have a much more effective weapon to hand.

3 Under the Licensing Act 1964, it is an offence to allow licensed premises to be the habitual resort or place of meeting of reputed prostitutes, and the police may oppose the renewal of the licence on these grounds. The importance of this provision is that the power to grant a licence is discretionary: in other words, the justices do not require the same high standard of proof as is needed to prove a criminal case. The police find it easier to take action in this way: a hotel soon finds that it loses more by not being allowed to sell liquor than it gains by tolerating prostitution.

Quite apart from these legal considerations, a hotel would be well advised to discourage prostitution for other reasons. It tends to upset other guests and, as we have seen, can be associated with a higher level of theft from rooms. Prostitution thus brings the hotel into disrepute and eventually leads to a decline in occupancies.

How do you discourage prostitution? Well, as we have already pointed out, you have a duty to prevent prostitutes from using your bars as a place to meet their clients, and you have the right to prevent anyone other than a guest from entering your sleeping accommodation.

Matters become more difficult if a genuine resident claims that a prostitute is his guest, because he is entitled to entertain his own friends as if he were in his own home. However, the hotel is also entitled to charge for the use of its accommodation, and a guest who is paying the single rate for a room with two beds in it can hardly complain if he is charged extra for double occupancy, providing this can be proved.

This particular situation calls for very tactful and delicate handling. One possible ploy if you suspect that a guest has actually taken a prostitute up to a room is to call his extension, announce that you have to check one of the fittings and ask (very politely) whether he would mind if someone came and did so in five minutes or so. This is said to have led to some very hurried departures down the back stairs.

Other forms of illegality

There are many illegal activities which guests might indulge in within the hotel's premises. It would be impossible to detail them all, but it might be helpful to have some general guidelines. It used to be the case that you had a legal duty to report any ‘felonies’ (serious criminal offences) which came to your attention, and could be prosecuted if you didn't. This no longer applies. You would still be expected to co-operate with the police in connection with really serious crimes, but you can exercise your discretion as far as ‘lesser’ ones are concerned.

Awkward situations can arise in connection with illegal drugs, especially because it is not always easy to distinguish these from legitimate medication. The use of hard drugs should always be regarded as a serious offence, especially if it involves third parties. On the other hand, many hoteliers would hesitate before reporting a guest's private use of a soft drug, though legally they should.

A guest who can be shown to have engaged in criminal activities on your premises is in breach of his contract of accommodation and can be asked to leave. This is another of those situations which requires great tact, and should really be handled by an experienced manager. However, there is always a first time for everyone, and you might find yourself having to do it some day. A common approach (not that this is a common situation) is to tell the guest, politely but firmly, that you are very sorry but you require the accommodation for another guest and must request that he leaves. Most guests are quite able to perceive the real message and will pack and go without too much argument. Those who try to bluster it out can be offered the choice between departing quietly or waiting for the police.

Death

The death of a guest does not constitute a threat in the usual sense of the word. However, it does cast a pall over the remaining guests’ enjoyment, and some may be so affected that they leave early, while other customers may cancel their reservations.

There is a widespread belief that hotels try to suppress any evidence of a guest's death, even to the extent of smuggling the body out in a laundry basket and bribing the ambulance drivers to report that he died on his way to the hospital rather than in the hotel. This is not true.

However, there is no point in drawing attention to the fact if this can be avoided. If a body is discovered in a room, the windows should be closed, the heating turned off, and the room double locked. The management should call a doctor, who is the best person to decide whether or not there are any suspicious circumstances. In most cases, death will be found to have been due to natural causes. The body will be discreetly removed via a service lift.

You may well find yourself having to deal with a deceased guest's wife or husband. It would be inconsiderate to expect the surviving partner to stay on in the same room, and you should make every effort to move him or her somewhere else. This situation calls for tact and discretion on the part of all staff concerned. It is not a time to press for payment of the bill, either.

Some hoteliers would quietly forget this, and most others would put it to one side, to be sent to the executors at a later date.

Assignments

1 Compare the nature, extent and seriousness of the security problems you would expect to find in the Tudor and Pancontinental Hotels.

2 The ‘Cranford’ is a medium-sized hotel falling within the scope of the Hotel Proprietors Act 1956 and displaying the appropriate notice. A female guest wishes to deposit jewellery at front office, but is advised that the safe is thought to be insecure and is currently being replaced. The manager offers to lock the jewellery in his office, but she refuses. That evening, she strikes up an acquaintanceship with another guest, who steals the jewellery and disappears. The other guest was a chance arrival who had been asked for and had paid the first night's rack rate in advance, being subsequently given two further nights’ stay on credit. Advise the management of the ‘Cranford’.

3 The front cover of this book shows a scene at a hotel's front desk. Imagine that you are the unlucky receptionist. How would you respond to requests for accommodation from these ‘chance’ guests? For reference, they are from front to rear:

(a) A person suffering from a potentially dangerous infectious disease.

(b) A visitor from Germany.

(c) A minor (i.e. someone under sixteen).

(d) A vagrant in ragged, dirty and possibly verminous clothing.

(e) A person who is drunk.

(f) A respectably dressed businessman of Afro-Caribbean ancestry.

(g) A couple who do not appear to be married.

(h) A hiker in anorak, shorts and heavy boots.

(i) A drug addict.

(j) A person who insists on being accompanied by a large and aggressive dog.

4 Imagine that you are a would-be walk-out. How would you go about obtaining a night's accommodation at a prestigious local hotel without paying for it? (Note: we are not trying to ENCOURAGE you to try this, merely to help you to anticipate the more obvious ‘ploys’ used by dishonest guests.)

5 How do you think security routines might develop over the next decade?