Chapter 1

Advance bookings

Introduction

We will begin our study of the work of front office with a look at its clerical functions. The first of these is dealing with advance bookings.

This is only the first part of a continuous process that runs through check-in (arrival and registration) to the guest's stay in-house and finally check-out (departure). It includes the preparation of the guest's bill and the process of settlement. We shall look at these aspects in the following chapters.

Hotels use a range of methods to deal with advance bookings. Manual systems require the completion of a number of different bits of paper, whereas computerized ones rely on a smaller number of keyboard entries. We shall describe the manual systems first, then show how the computerized ones differ from them.

Whatever the method used, the system has to be able to satisfy the following aims:

1 Produce a written record of all reservations.

2 Permit the receptionist to recognize unwanted guests in time to take appropriate action.

3 Provide immediate access to room availability data on any date, thus allowing the reservation staff to accept or reject requests without delay.

4 Produce a daily arrivals list.

5 Enable management to maximize occupancy and room revenue.

The actual process is set out in Figure 8. Note that this is an ‘idealized’ version. Many hotels omit some of the stages (consulting a black list, for instance), or deal with functions like the diary in different ways. A computerized system consolidates some of the entries, reducing the amount of copying and facilitating analysis.

Enquiries

The process of making a booking begins with an enquiry. Guests contact hotels in various ways. The most common are as follows:

1 In person. Such guests are commonly known as ‘walk-ins’. They are often people who are travelling unexpectedly, or touring an area ‘out of season’. Since few hotels are anything like 100 per cent full, this approach is often successful. Most ‘walk-ins’ need accommodation immediately, but occasionally they want to make advance bookings. Sometimes a visitor knows that he will be coming back to the area later and decides to make an advance reservation there and then. Another possibility is that a local resident wants to make an advance booking on behalf of someone else. This can be particularly important with regard to group bookings such as tours or conferences.

2 Letter. In the old days advance bookings generally took this form and were often for several months ahead. Nowadays, letter writing has gone out of fashion, but a considerable number of holiday bookings are still made in this way. Letters offer the great advantage of being clear, unambiguous and permanent. A client may well agree to the details of a group booking face to face or over the telephone, but it is still good practice to set them out in the form of a follow-up letter. That way, both sides have a record of what was decided, which helps to eliminate subsequent arguments. Letters are also useful evidence that a contract was actually agreed. Hotels suffer quite severely from people who book and then don't turn up (they are called ‘no shows’). That is why you should ask for a letter of confirmation whenever possible. Written confirmation is also useful for the guest, who has a clear interest in knowing that the accommodation he has booked will actually be waiting for him when he arrives. Consequently, you should send the guest a confirmation as a matter of course.

3 Telephone. Nowadays bookings are far more likely to come in the form of telephone calls. These generally request accommodation for only a day or two ahead (and sometimes only a few hours). The telephone is fast and convenient, but it suffers from the major disadvantage that it does not provide a permanent record (answering machines record messages but not usually two-way conversations). This means that the speakers at either end of the line have to make their own notes of what was agreed.

4 Fax (facsimile transmission). This became very popular in the 1980s, though some hotels had been using internal fax systems long before that. Fax uses electronic scanning techniques to send copies of documents over ordinary telephone lines to a special machine which prints out an identical copy at the other end. It can be used to send plans, diagrams and even pictures, but its main use is to transmit memos and letters. A fax will print out messages received even if it is left unmanned. Using fax, a would-be guest can send a booking instantaneously to a hotel on the other side of the world, and receive back written confirmation within a matter of hours or even minutes. The advantages are obvious, and we can expect to see all kinds of ingenious developments in the near future.

5 The Internet and other computerized communications. Written records are becoming increasingly old-fashioned, and what is called ‘email’ (electronic mail) is expanding rapidly. This means that a provincial travel agency's computer can ‘talk’ to a hotel's computer in another city, making bookings directly and leaving only an electronic record. Furthermore, it is possible for an individual guest to make a booking directly through his personal computer, which will retain the details in its memory. These developments are likely to have an important effect on marketing, which is discussed more fully later.

Figure 8 Pre-arrivals procedure

No single means of communication is ideal in terms of:

![]() speed

speed

![]() convenience

convenience

![]() economy

economy

This means that we are likely to continue to see a mixture in use.

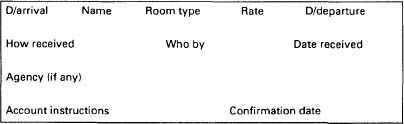

Reservation forms

However the booking is received, it has to be recorded. This record is generally called a reservation form. The actual layout will vary from hotel to hotel, but will typically include much of that shown in Figure 9.

There are several arguments in favour of using such forms:

1 They provide a permanent record.

2 They summarize information in a standard format. Even written communications can vary considerably in terms of form and content. Transferring the data from the original source to a standard reservation form makes it easier to check.

3 They act as a ‘prompt’ sheet. Would-be guests may leave out important information, and a junior reservation clerk in a hurry might well forget to ask something vital unless she is prompted by having to complete a standardized form.

4 They enable management to find out who handled the booking. The practice of requiring reservation staff to sign or initial every reservation form they deal with is useful in case there are any queries or errors.

5 They can provide a running check on progress. Instead of a bulky file containing the guest's original letter of enquiry, the hotel's response, the guest's booking, the hotel's confirmation and any subsequent communications, you can simply tick off a series of boxes, such as ‘provisional’ and ‘confirmed’.

6 They can include information about the sources of bookings (e.g. private, travel agent, etc.) and how they are made, which is useful for marketing analysis purposes.

Figure 9 Specimen reservation form

There is still some disagreement about whether a computerized reservation system really requires the use of a separate reservation form. Virtually all booking programs present the reservation staff with an on-screen reservation form, and the idea of having to complete a paper version before entering the data into the computer system seems like a waste of time. On the other hand, entering data via a keyboard currently suffers from two significant limitations:

1 It is usually slower than using a pen because you can't ‘skip’ fields. Instead, you have to move through them in order, pressing ‘return’ to jump to the next if you want to leave the current one blank.

2 You need to have both hands free, which means that answering the telephone requires earphones and a mouthpiece.

In addition, many reservation staff find that they have to concentrate on operating the computer, and this makes it harder for them to give their full attention to the caller.

Consequently, many computerized systems operate a ‘two-stage’ process whereby the reservation clerk uses a form while actually taking the booking, then enters the data into the computer during a later quiet period. This means that the booking records will not be completely up to date, but as long as the advance bookings are nowhere near full a half hour's delay is not really serious (in other words, you can take an additional booking without worrying about running out of rooms).

The black list

A black list is simply a record of people whom the hotel does not wish to accept as guests. It may be kept in book form or as a set of loose-leaf entries. There are only two essential requirements:

1 It should be easy to consult.

2 It should NOT be accessible to guests.

There are a number of ways in which individuals can find themselves on a black list:

1 They may have stayed at your hotel before and then ‘skipped’ (i.e. run off without paying their bill). You might think that such a person won't come back, or use the same name if he does, but it CAN happen, especially if he thinks your security system is so poor that you won't spot him the second time. Alternatively, he may have tried the same trick at another hotel. Hotels commonly exchange information about suspect characters, and many black lists are compiled in conjunction with other establishments.

2 They may have shown themselves to be obnoxious in some way, perhaps by becoming violently drunk, abusive or quarrelsome and thereby disturbing other guests, or by damaging your fixtures and fittings.

3 You may suspect them of having stolen something, either from you or another guest. Confidence tricksters and walk-in thieves find expensive hotels happy hunting grounds, and you don't want to encourage them. You may not be able to prove anything, but you do have an obligation to protect your other customers.

4 Finally, they may be employed by a firm whose solvency is in some doubt. Some companies are notoriously slow in paying their bills, and you simply decide that it isn't worth the hassle and aggravation of trying to collect. This may seem unfair on the individual, but it is actually one of the more common reason, for blacklisting.

What can you say when you recognize that a would-be guest's name is on the black list? Usually you reply, ‘I'm sorry, we're full’. Coincidentally, you are also full the following night, the following week and even the following year. Such callers quickly get the message. Be careful about saying ‘We don't want you’ because of the innkeeper's duty to accept any bona fide traveller, and be even more cautious about giving your reasons (after all, suspicion is not the same as proof).

In practice, the black list has been more theoretical than real in recent years. In the past, many bookings arrived in the form of letters, and the receptionist had time to consult the list before replying. Nowadays, far more of the bookings come via telephone calls, and many of these are made on behalf of third parties who may not even be named until much closer to the time of arrival (this is often the case with group tours or company representatives). As a result, a great many are now taken without reference to any form of black list. However, it still makes sense to ask ‘Do we really want this guest?’ before you take a booking, and advances in computer technology may well restore the black list to something like its old importance.

A final point is that the black list need not just be a list of persons whom we wish to reject. It can also be used to ‘flag’ VIPs or anyone whom you think might require special treatment.

Offering alternatives

We will discuss this in more detail under ‘Sales’.

The bookings diary

The bookings diary's main purpose is to provide a list of arrivals on any particular night. It is not so much a specific document as a function, for hotels vary very much in the way they record this information. The diary's importance is shown by the fact that manual systems normally produce it by means of an additional entry, which is inevitably expensive in terms of clerical time. The main systems available are outlined below.

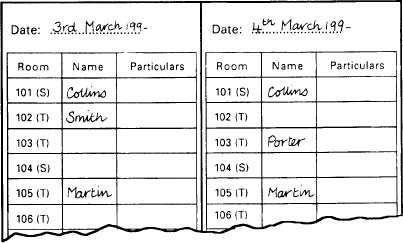

The traditional bookings diary

This was just what its name suggests: a daily diary in which reservations staff listed all the arrivals due on that particular date. It was usually kept on a loose-leaf basis, with pages being removed from the front as the dates were reached, and new blank pages being added at the back. Page layouts varied, but typically included those shown in Figure 10.

Figure 10 Traditional bookings diary

Note that the entries were only made for the date of arrival: the stays themselves were shown on a separate document called a ‘bookings chart’. Diary entries were made consecutively: in other words, the first booking taken for any particular date appeared on the first line, the second on the line below and so on.

This traditional bookings diary was typical of the old approach to clerical operations, which required transactions to be transcribed laboriously into ‘journals’ or ‘day books’ before they were transferred to the accounts. Eventually more and more managers realized that the bookings diary could be replaced by a set of reservation forms filed in batches according to date of arrival, then arranged in alphabetical order within the batches. This was more efficient because it involved less copying, and also produced an alphabetically arranged arrivals list.

The Whitney advance bookings rack

Another approach was pioneered by the American Whitney Corporation. It is known as the Whitney System. We shall be describing other aspects of the Whitney System later: at the moment we are only concerned with the advance bookings rack.

The Whitney System used to be most common in large and busy hotels, and has consequently tended to be superseded by computers nowadays. However, it may still be found acting as a back-up manual system and you need to be familiar with it.

The system is based on the use of standard sized cards or ‘Shannon slips’. These can be colour coded to show various kinds of reservation (group, airline, VIP, etc.). It is possible to obtain slips made of NCR (‘no carbon required’) paper which allow you to produce additional copies (e.g. for switchboard) with no extra work.

The slips are designed to be placed in light metal carriers, which fit into vertical racks in such a way that only the top part of the slip can be seen. Because of this, it is usual to reserve the top line for the essential information and use the rest of the slip for less important details. It is possible to consult this whenever necessary because the slips and their carriers can easily be pushed upwards in the rack. A typical layout for an advance booking slip is shown in Figure 11.

Figure 12 Whitney advance reservation rack

The set of racks holding the slips acts as a bookings diary. There are normally a number of these racks, arranged side by side within a framework hung vertically against a wall and capable of being moved along or lifted out if necessary. Special ‘header’ slips are used to divide the contents into different sections. Usually there will be a separate section for each of the next thirty or so days, one for each of the succeeding twelve months, then a single one for any bookings beyond that. As each day is reached the rack in question is taken out and the others moved along, so that the whole mass of information is constantly being kept up to date.

The slips in their carriers can be moved around just as easily within the racks. This means that it is possible to subdivide next month's bookings into weeks as soon as they start to accumulate. The weeks themselves can be broken down into days just as easily. As we have seen, the slips can be colour coded, giving a quick ‘at-a-glance’ overview of the main sources of business.

Just as important is the fact that the slips can be kept in alphabetical order. This was impossible with the traditional bookings diary, where written entries had to be made as and when the bookings came in. Using a Whitney rack, ‘Aaronson’ can always be made to precede ‘Barclay’, which is a considerable help if you are trying to find the details of a booking in a hurry. Amendments don't affect this: you simply take the slip out of the rack and place it somewhere else without disturbing the order of the other slips.

The Whitney advance bookings rack offers a number of important advantages:

![]() Bookings can always be kept in date of arrival order, subdivided alphabetically.

Bookings can always be kept in date of arrival order, subdivided alphabetically.

![]() The racks and carriers can be reused, so that running expenses are limited to the cost of the paper slips.

The racks and carriers can be reused, so that running expenses are limited to the cost of the paper slips.

![]() The racks can be fixed vertically, which saves space (often at a premium in hotel back offices).

The racks can be fixed vertically, which saves space (often at a premium in hotel back offices).

Room availability records

The next stage in the procedure requires us to check whether we actually have a room available. This is the most important part of the process, and involves using the room availability records, or bookings charts.

There are three alternative systems which you may find in use in different kinds of hotels:

1 The bedroom book (very small hotels).

2 The conventional chart (small to medium hotels).

3 The density chart (medium to large hotels).

In addition, some hotels use stop/go or space availability charts to supplement the main records.

The general principles on which these systems are constructed are the same whether they are printed on paper or through the medium of a computer screen. If you wish to understand the latter, it helps to follow things through on paper first. In any case, there are still strong arguments for a paper-based system in a small to medium-sized hotel. It is often much faster to operate than a computer program, since you don't have to get into ‘reservation mode’ and then type in the date you want to check. Moreover, a paper chart doesn't break down or suffer from power failures.

The bedroom book (reservations journal)

This is similar to the bookings diary except that we enter the guest's name for every night of his stay. It is usual to have a list of the room types and numbers down the side of each page so that we can make sure we don't put a couple into a single room, or make them change rooms during their stay. A typical bedroom book is shown in Figure 13.

Clearly, entering a guest's name on every night of his stay increases the amount of writing to be done. If he was staying for seven days, we might have to write out his name seven times, though it is usually possible to devise some short cuts. Moreover, the page size limits the number of rooms we can book using this system. Consequently, bedroom books are really only suitable for small hotels, especially those with a high proportion of one-night stays. Small bed and breakfast establishments in areas where there is a lot of touring find this system perfectly satisfactory.

The conventional chart

This is a development of the bedroom book which is designed to be easier to read and more convenient to operate. It is laid out as shown in Figure 14.

The guests’ names are written in block capitals and their arrival and departure dates are indicated by ‘<“ and ‘>‘, respectively. The usual convention is that the date column represents the night of the guest's stay, so that a guest arriving on the 1st and leaving on the morning of the 2nd would be recorded under the 1st only. As a result, the point of the arrow is usually placed against the vertical line. However, some reservation staff place it in the middle of the column to indicate that the guest is actually staying until mid-morning. This is technically correct, but is harder to read and thus liable to lead to misunderstandings.

The conventional chart is simple to operate and shows most of the information the reservations staff need to know in an easy-to-read form. It is easy to enter a lengthy stay. The chart can display an entire month of bookings on one sheet of paper, and the left-hand columns can show the type of room, any interconnections, and even the rack rates if so desired.

Nevertheless, the conventional chart has a number of limitations. These become more serious the larger and busier the hotel. They are (in ascending order of importance) as follows:

1 The so-called ‘long name/short stay’ problem. Imagine that you have someone called ‘Foulkes-Fotheringham’ staying for just one night. It can be difficult to fit such a name into a relatively small space, and this sometimes reduces inexperienced staff to panic. However, you can always abbreviate it to ‘F-F’ since the full details are available elsewhere.

2 The chart quickly becomes untidy because of amendments and corrections. It is usually printed on stout paper with the entries made in pencil to allow for this. Nevertheless, an extensively altered chart generally looks more than a little messy.

3 You can only get 30-60 lines on one sheet if you are going to write the names legibly, which means that this chart is limited to medium-sized hotels.

4 It is not easy to count the number of free rooms on any one night. If you receive a request for a group booking, you have to run your finger down the appropriate date column, counting the number of blank spaces and checking to see whether they are singles or twins. This limitation becomes important in larger hotels with a high proportion of group bookings.

5 It is difficult to overbook, since an entry on the chart is synonymous with a room reservation. You can make provision for this by leaving a number of blank lines at the bottom of the chart, but it isn't always easy to know when you should use these since, as point 4 above indicates, the chart is not designed to show the total number of rooms let very clearly.

6 Most important of all, the conventional chart makes it necessary to select a room when the guest books. In practice, most large hotels find it easier to select a room when he arrives. Rooms can then be allocated as they become ready, rather than the housekeeping staff having to rush to prepare particular ones for early arrivals. Allocating rooms in advance can also lead to the creation of awkward ‘gaps’ which are then difficult to fill. You might find that Room 102 (a twin) is free on Monday and Room 103 (also a twin) is free on Tuesday. You have a twin available on both nights, but they are not the same rooms, which makes it difficult to accept a two-night booking without some complicated last minute ‘switching’.

These last three factors make it difficult to maximize occupancy using the conventional chart. However, you would have to use it if all your rooms were different and guests were likely to want one in particular. Conventional charts are thus best suited to hotels with:

1 fewer than sixty rooms

2 non-standard accommodation

3 relatively long stays, especially of the ‘end-on’ (i.e. everyone arriving and departing on the same day) type

4 few short notice group bookings

5 few ‘no shows’ (i.e. little need to overbook)

Figure 15 Standard density chart

These features tend to be characteristic of the smaller, older type of resort hotel, though you should note that the second and third points also apply to timeshare letting. However, most modern establishments find it more convenient to use the next type of chart to be discussed.

The density chart

This is a development of the conventional chart, designed to overcome the latter's weaknesses. It can only be used in hotels with standardized rooms because its fundamental principle is that all rooms of a particular type are ‘blocked’, i.e. grouped together. The reservations clerk does not reserve a specific room: she only books one of the particular type requested. The actual room allocation is done on arrival. This means that the guest does not know which room he is going to occupy until he arrives, but this does not matter since all rooms of the same type are identical.

In a density chart, the vertical columns indicate the dates, as in the conventional chart, though they are narrower because you only put a stroke (/) instead of writing in the guest's name. However, the horizontal rows do NOT indicate room numbers as in the conventional chart. Instead, they show the total number of rooms of the specified type.

The density chart is completed as follows. New bookings are entered as strokes in the appropriate date columns. Strokes are always made in the first free space reading from the top. This means that a series of strokes representing a two- or three-day booking does not have to be on the same horizontal line. In fact, this becomes unusual once the chart has a number of previous entries on it (to check this, look at our example and try entering a three-night single booking commencing on the 1st).

Newcomers to the density chart sometimes fear that this might mean guests having to change rooms during their stays. It doesn't. It would if we were using a conventional chart, because in that case each row represents a specific room. With the density chart the row merely represents a room TYPE. There must be a room free for any subsequent reservation, otherwise you would not be able to get the booking onto the chart (even if you use the minus or overbooking rows, you are simply assuming that one of the other bookings won't appear).

Group bookings can be indicated by drawing a rough circle around a group of strokes, as shown. The group's reference number can be added for greater clarity.

The density chart offers a number of important advantages over the conventional version, though there are also some corresponding disadvantages. These are as follows:

1 It is easier to complete since you only have to make a stroke rather than printing the guest's name in full. The corresponding disadvantages are that it is easier to make mistakes, and more difficult to check them since you have no idea which stroke represents which guest.

2 You can fit more rooms onto a density chart because the ‘boxes’ can be much smaller than on a conventional chart. This makes the density chart particularly suitable for large hotels (even so, really large ones need one page for each night, rather than being able to show an entire month's bookings on one sheet). The disadvantage (as we have already noted) is that you can only use it in hotels with standard rooms. Attempts to use it in older hotels where the rooms vary considerably in terms of attractiveness (even if they are all similar in theory) run up against the problem of the regular guest who begins to ask for a specific room. This is not easy to guarantee when you are using a density chart.

3 It allows you to see at a glance just how many rooms of a particular type you have left. In our example you can see that on the night of the 6th we have two singles free (all you have to do is run your finger down the relevant column, then across to the ‘total’ figure on the left). This is very useful if you are handling lots of block bookings.

4 It makes it easier to handle overbooking. You can see at a glance just where you are and control your overbooking by using the ‘minus’ rows. This helps you to maximize occupancy.

These features appeal particularly to large modern hotels, which generally have standardized rooms and cater for a lot of block bookings and business trade (the latter often characterized by a high proportion of no shows). Nowadays, such hotels use computerized reservation systems, but their room availability displays are still based on density chart principles.

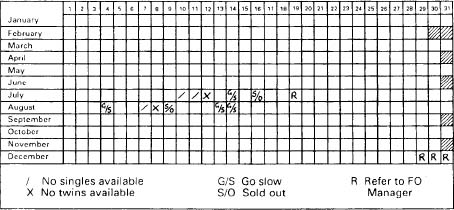

Stop/go or space availability charts

Convenient though it is, there can only be one density chart in a hotel. This sometimes proved inconvenient in very large establishments where five or six reservations clerks might all find themselves taking bookings at once.

The answer was a ‘stop/go’ chart. This did not replace the main chart, but merely indicated the future letting position at a glance so that the clerks could tell whether it was safe to go ahead and take a booking. It commonly looked something like the example shown in Figure 16.

The codings were written in pencil or some other erasable medium. They signalled the room availability status. If a particular date was clear, the staff could go ahead and let rooms without worrying. ‘G/S’ (go slow) might mean that they could sell one or two rooms but had to check whether they could accept a group.

Stop/go charts were limited to large hotels. In theory they are not necessary in a computerized system because each clerk can see the current room availability situation on her own VDU. However, checking future dates can be time-consuming, and stop/go charts can still be useful.

Computerized reservations

Computerized reservations follow many of the same stages as manual ones, though they look very different since everything appears on the screen, usually with a series of ‘prompts’. The details will vary from one system to another, but in general the process is as follows:

Figure 16 Stop/go or space availability chart

1 Enter the advance reservations part of the program via the ‘main menu’. This step is equivalent to a reservation clerk turning to the chart.

2 Call up the room availability display for the night in question. This always means typing in the required date via the keyboard. The computer will then show you how many rooms are available (this is very similar to the density chart, with the added advantage that the computer counts up the number of free rooms instead of you having to do it!). The computer will generally display up to fourteen successive nights as well in case you have to book a lengthy stay: it is usually possible to ‘flip’ backwards or forwards in fourteen-night increments with a simple key press. Systems generally have a ‘booking horizon’ of something like two years or so, which is more than sufficient for most purposes. The display will look something like that shown in Figure 17 (this assumes a hotel with 50 singles, 100 twins and 50 doubles). This display is mostly self-evident. The ‘occupancy percentages’ are room occupancies.

3 Enter the bookings section of the program. This is really a computerized version of the reservation form. It will look something like the example shown in Figure 18.

4 The abbreviations vary from program to program but are mostly self-explanatory, and soon become familiar with use. In this example:

– ‘ARR’ means arrival date

– ‘NTS’ means the number of nights’ stay

– ‘DEP’ the departure date

– ‘RM Type’ the type of room

– ‘NO’ the actual number of rooms being booked (remember that families may book two or more)

– ‘TERMS’ the type of package (weekend break, bed and breakfast, etc.)

– ‘RATE’ the price agreed

– ‘ETA’ means expected time of arrival

– ‘SHARE’ establishes whether or not the guest is willing to share a room (often the case with conference delegates, for instance)

– ‘NAT’ means nationality

– ‘GROUP’ the particular tour or conference (these are usually given reference numbers or codes)

– ‘DEPOSIT’, ‘DUE’ and ‘REC'D’ are self-explanatory

– ‘RLSE’ means release date (i.e. the date by which the computer will automatically cancel the booking unless a deposit has been received)

– ‘GTD’ asks whether the booking is ‘guaranteed’ or not (see below). Such bookings generally depend on the method of payment agreed, so the next two ‘fields’ (‘PAY'T’ and ‘CARD/VOUCHER NO’) relate to that

– Finally, ‘COMMENTS’ allows any individual requests to be noted.

5 There may well be other ‘fields’. Some programs require you to classify guests by type (e.g. regular or VIP), or allow cross-reference to a pre-existing guest history file. Virtually all will require you to identify yourself by adding your own identification code (if you don't, or if the code is invalid, the program won't allow you to proceed any further). This is the equivalent of your initialling the reservation form. Programs usually allow you to ‘skip’ fields if these are irrelevant to that particular booking. They will also allow you to pre-program particular keys in order to save on typing time (for instance, the ‘function’ keys may be programmed so that ‘F2’ produces ‘USA’ in response to the ‘nationality?’ prompt). Finally, they will allow you to review the booking details and make any necessary corrections before you finally press the ‘Return’ or ‘Enter’ key and commit it to the computer's memory. Even then, all is not lost, for the programs will allow you to cancel or amend bookings, though they will usually retain records for security reasons. It is thus often possible to enter, cancel and then reinstate a booking without having to go through the lengthy business of retyping the details in through the keyboard.

6 Many systems will also allow you to reserve specific rooms (in other words, they will double as a conventional chart).

7 Once the booking has been put into the computer's memory, a great many operations can be handled automatically. The most important of these are as follows:

– The room count is adjusted to reduce the number of rooms available. If a specific room has been reserved, that room is ‘flagged’ so that it cannot be let to anyone else. The program thus acts as both a density and a conventional chart.

– A list of expected arrivals is prepared for each future date. This list is always up to date, and always in alphabetical order. Many programs will also allow you to extract the names of particular types of guests (e.g. VIPs), or to search the files for particular names (this is useful if you receive an enquiry about a guest who has not yet arrived). In this way the computer can double as a bookings diary and an arrivals (or departures) list.

– Finally, the computer can provide up-to-date details of expected occupancies and room revenue figures at the press of a key. As we shall see later on, this is important when we are trying to maximize revenue through what is known as ‘yield management’.

Figure 17 Advance reservations screen

Guaranteed reservations

As we saw when we looked at computerized bookings, the question of whether a reservation is ‘guaranteed’ or not is an important one. A guaranteed booking is one for which the hotel receives payment whether or not the guest turns up. Apart from cases where the room is actually paid for in advance, there are two ways in which this can happen:

1 Special agreements. These are usually cases where a company asks the hotel to ‘hold’ rooms for it whether they are used or not.

2 Credit card bookings. These are guaranteed unless there is a specific agreement to the contrary, which helps to explain why hotels much prefer this particular form of payment. They account for the vast majority of guaranteed bookings.

Note that it is only the accommodation charge that is guaranteed, not any meals that the guest might have taken had he stayed.

Assignments

1 Describe the type of advance booking system you would expect to find in the Tudor Hotel.

2 Describe the type of advance booking system you would expect to find in the Pancontinental Hotel.

3 Obtain specimens of the type of advance booking documents and an outline of the procedures used at a selection of local hotels, and compare these with one another, relating their characteristics to the type of hotel involved.

4 Discuss the arguments against and in favour of hand-written reservation forms in hotels with computerized advance booking systems.

5 Describe the nature and purpose of the black list. Assess its current importance, and discuss how it might develop over the next decade.