Although Senge acknowledged that he was not the first person to write about organizational learning, his presentation seems to imply that his ideas have broader relevance than prior perspectives. Of course, he may have been unaware of the earlier research about organizational learning. He could have used the prior research he ignored to bolster his case for the need to approach organizational learning differently. The very fact that most organizational learning is ineffective or eventually causes problems gives reason for readers to pay attention to new ideas. At the same time, Senge’s lessons do not focus on the kinds of organizational learning that typically do occur. He is not naïve and he recognizes that human behavior often impedes learning and that much organizational learning goes amiss. He is proposing that a more effective kind of learning could be occurring. He is a visionary who is trying to describe an idealized organizational form that does not exist today but, he says, could exist in the future.

What Senge said and how he said it

The Fifth Discipline has unusual properties. This fact should surprise no one, of course, because the book has had extreme success far beyond that of almost all other books. Even if the book’s success is partly due to its timing and environment, it is unlikely to look exactly like less successful books. However, the book has properties that make it both attractive and unattractive to readers. Some evidence suggests that The Fifth Discipline is both easy to read and yet unread, that its popularity derives in part from its appeal for readers who see themselves as unusual, that its ideas have rarely been implemented and implementation has yielded unclear results. Does The Fifth Discipline afford a prototype for other books that aim at societal influence? Or has The Fifth Discipline succeeded because of its timing and despite its idiosyncrasies?

Much of The Fifth Discipline is very easy to understand, down-to-earth, and practical. Within the general themes, the text is fragmented and episodic. This fragmentation of text allows readers to read and digest segments. One need not read an entire chapter, sometimes not even an entire page, in order to extract a distinct point. Many of the segments tell great stories about human behavior, restate truisms, or contain quotable phrases. Although these segments fit into Senge’s broader themes, they also stand alone as epigrams or illustrations of specific lessons (Ortenblad, 2007). For example, time delay in physiological reactions to ingesting food causes people to eat too much; trying to swim against a strong current may sap a swimmer’s strength without producing progress toward shore. Such illustrations let readers draw useful lessons whether or not they buy into Senge’s broader themes, and they make the lessons easy to remember. At the same time, the broader themes give the book some coherence and create an impression of communicating a message of grand significance.

However, the book also forwards ideas that are so abstract that many people do not see their value and the ideas are difficult and expensive to implement (Smith, 2008). The book offers rhapsodic discussion of interlinked systems, their importance and prevalence. It recognizes the complexity of organizational and behavioral challenges. It advocates holistic and dynamic appreciation of social systems (including organizations), and it criticizes much management practice as misguided efforts to apply simplistic mental frameworks to complex situations. Effective management, it says, requires ‘systems thinking’—appreciation for interdependencies and change over time. The book (1990:14) asserts that effective organizational learning involves creativity as well as adaptation: ‘it is not enough to survive. ‘Survival learning’ or what is more often termed ‘adaptive learning’ is important—indeed it is necessary. But for a learning organization, ‘adaptive learning’ must be joined by ‘generative learning’, learning that enhances our capacity to create’. Indeed, Senge concluded The Fifth Discipline with titillating predictions about a ‘sixth discipline.’ In an obscure manner, he suggested that an intellectual sequel awaits once the first five disciplines reach critical mass. Senge (1990: 363) predicted, ‘there will be other innovations in the future’ and ‘perhaps one or two developments emerging from seemingly unlikely places, will lead to a wholly new discipline that we cannot even grasp today.’

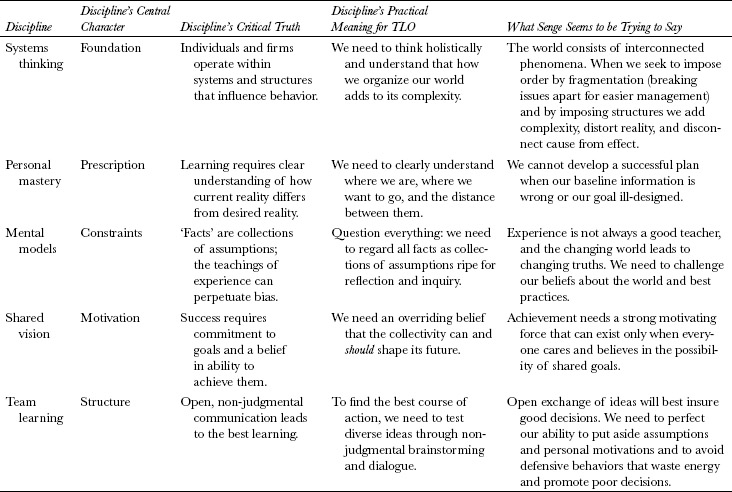

Of course, his conceptual framework implies that Senge’s prescriptions are themselves interdependent and idealistic. He urges people to practice five ‘disciplines,’ which Table 11.2 summarizes. The disciplines deal with individuals, groups, and whole organizations; and they overlap each other to some degree. Indeed, this overlap contributes to making the book very dense and difficult to synthesize. For example, in his discussion of systems thinking, Senge explains that the mental models are in many ways the results of the structures people impose on systems. In their efforts to understand and manage systems, people break systems down into more manageable pieces, organize them into structures, and then interpret them in these fragmented and organized forms. The structures may be literal but they are more often concepts about processes, procedures, or hierarchies. These imposed structures alter understandings of the entire system, often making the understandings less accurate. The structures also make systems more complex and hinder people’s ability to learn. Thus, Senge prescribes awareness, reassessment of goals, and open exchange of ideas—individual and group actions—to improve system-wide learning.

Table 11.2 Senge’s five disciplines

Much of The Fifth Discipline is bizarrely abstract, nearly impossible to decipher, and impossible to translate into practical actions. People who have tried to use Senge’s ideas have raised questions about The Fifth Discipline’s practical implications. Malone (1997: 72) pointed to three problems: (1) TLO has turned into training; (2) TLO had slipped into an MIS sinkhole; (3) ‘No one has yet figured out quite how an organization “learns” the right things.’ Smith (2001) suggested that Senge’s work was ‘simply too idealistic’ and he observed that the self-reflection associated with the five disciplines daunts most people; many employees just want to earn a living and have no interest in the greater ideals of the organization. Ortenblad (2007) reported that managers do not read the book because it is so difficult to read and he complained that Senge provided no blueprint for implementation. Senge himself has expressed disappointment that companies ‘either paid no more than lip service to [The Fifth Discipline] or turned their backs on it altogether’ (Senge and Crainer, 2008: 71). In 2008, The Learning Organization journal published a fifteen-year retrospective issue on both TLO concept and on the journal itself. The editor concluded that ‘although the learning organization concept is deemed narrow and out of date, it is judged to have significant positive influence on organizational thinking’ (Smith, 2008: 441).

The foundation of TLO—systems analysis—may be its weakest component. The Fifth Discipline describes ten systems archetypes, which Senge characterized as tools to help managers learn systems thinking. The archetypes mix heterogeneous elements at different levels of abstraction—simplistic explanations involving phenomena such as delay and eroding goals alternate with complex theoretical descriptions such as the ‘tragedy of the commons’ and ‘growth and underinvestment.’ The conglomerate character of these archetypes underscores the substantial challenge of overcoming human nature and conditioning needed to achieve a broad, systemic mindset.

Senge clarified why people have trouble seeing the bigger picture and why systems thinking poses so many problems, but he nevertheless continued to insist that systems analysis should be the focal point of TLO. In doing so, Senge was attempting to override The Law of Requisite Variety, which says that for people to understand their environments, human comprehension abilities must be as complex and diverse as the environments (Ashby, 1958). However, human rationality is a rather crude and imperfect tool because humans need and demand simplicity. When Box and Draper (1969) attempted to use experiments to improve factory operations, they discovered that practical experiments have to alter no more than two or three variables at a time because the people who interpret experimental findings cannot make sense of interactions among four or more variables. Faust (1984) also observed that scientists have difficulties understanding interactions among more than three variables (Goldberg, 1970; Meehl, 1954). Faust remarked that the great theoretical contributions in the physical sciences have exhibited parsimony and simplicity rather than complexity, and he speculated that parsimonious theories have been very influential not because the physical universe is simple but because people find simple theories understandable.

A real-life example illustrates the constraints that human cognitive limitations place on systems analysis. In the summer of 2009, PA Consulting submitted a diagram to the officers who were in charge of US troops fighting in Afghanistan. The diagram presented the consulting company’s analysis of the relationships officers ought to consider in planning military and political strategies—scores of relationships among scores of variables such as accomplishments, beliefs, capabilities, crime, expectations, fears, interest groups, manpower, needs, outcomes, perceptions, policies, political support, priorities, resources, setbacks, territory controlled, and time elapsed. According to Bumiller (2010), the officers reacted with laughter to this diagram’s impenetrable complexity.

However, the complexity and abstraction of Senge’s analysis may enable some readers to feel proud that they perceive issues and solutions that other people cannot see, and so these properties contribute to the development of a collectivity of superior insiders who appreciate Senge’s message. The support organization Senge created, The Society for Organizational Learning, has already drifted away from the ideas in The Fifth Discipline. The Society has recently been promoting ‘Theory U’ which promises to teach us ‘to connect to our essential Self in the realm of presencing’ and to use ‘principles and practices that allow everyone to participate fully in co-creating and bringing forth the desired future that is working to emerge through us.’ Similarly, much of Senge’s own recent writing and speaking has centered on the more trendy topic of sustainability.

When Senge said it: Is TLO just a fad or more than that?

Perhaps The Fifth Discipline has succeeded mainly because it fits into its time and place, because it captures the spirit of its age. In his Foreword to the 2006 edition of The Fifth Discipline, Senge explained that he had realized in 1987 ‘that “the learning organization” would likely become a new management fad.’ He assumed that the fad would rise and fall and he wanted to establish key ideas early on at the beginning of this fad and especially he wanted to influence the residual of ideas that remained after this fad abated.

Various commentators have declared TLO to be a short-term fad—indeed, a fad that is ending or has ended. Malone (1997) included TLO in a list of ‘management fads which have come and gone.’ Hodgetts, Luthans, and Lee (1998) claimed that TLO was an intermediate stage in a developmental evolution toward ‘world-class organizations.’ Scarbourgh and Swan (2001) evaluated ProQuest references to ‘learning organization’ and to ‘knowledge management’ from 1990 to 1998, and concluded that TLO had become unfashionable and had been replaced by knowledge management. Rebelo and Gomes (2008: 294) inferred that ‘academic and managerial interest in these [organizational learning and TLO] started to wane slightly and the suspicion that organizational learning was merely a fashion has increased, as have the critical voices around it.’

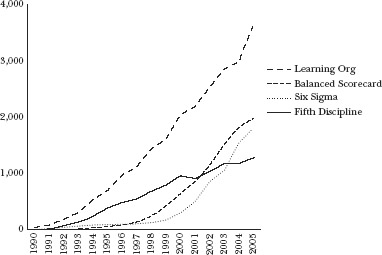

Nevertheless, data do not yet demonstrate clearly that enthusiasm for TLO has waned. Figures 11.2a, Figures 11.2b, and Figures 11.2c compare the popularity of TLO with two management ideas that were popular from 1990 to 2005—‘six sigma’ quality improvement and the ‘balanced scorecard’ assessment of business performance. The graphs show the numbers of documents that cited The Fifth Discipline and the numbers of documents that used the phrases ‘learning organization,’ ‘six sigma,’ or ‘balanced scorecard.’ Figure 11.2a presents absolute numbers; many more documents used the phrase ‘learning organization’ than used the phrases ‘six sigma’ or ‘balanced scorecard.’ Only forty percent of the documents that used the phrase ‘learning organization’ also mentioned Senge; ‘learning organization’ is a broader concept than Senge’s TLO.

Figure 11.2a Citations About Three Management Ideas

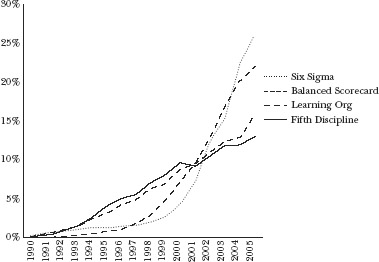

Figure 11.2b Normalized Citations About Three Management Ideas (Normalized by Citations in First Sixteen Years)

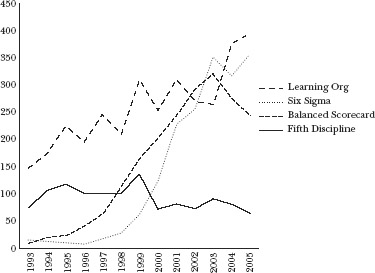

Figure 11.2c Changes in Citations About Three Management Ideas (Three-Year Averages)

To highlight the different shapes of the curves, Figure 11.2b shows data normalized so that all four lines appear to describe the same total number of documents over the sixteen years, and Figure 11.2c shows changes averaged over three years.

Citations to The Fifth Discipline and documents that mention ‘learning organization’ have increased more linearly than documents that mention the other two management ideas. Both six sigma and the balanced scorecard drew very few citations during the early 1990s; then both began rapid growth just before 2000. Rapid growth could be a sign that people are becoming more likely to do something as they see more people doing it, possibly because prevalence confers legitimacy. When people or organizations adopt an innovation partly because many other people or organizations have adopted this innovation, a bandwagon effect occurs. On the other hand, some studies have shown that rapid growth in the adoption of an innovation correlates with a parallel increase in marketing efforts, and Abrahamson and Rosenkopf (1993) ran simulations that showed very small differences could have massive impacts on the rise and collapse in the popularity of innovations. It is also worthwhile to beware of fallacious inferences about the processes that generate time series: a given process can generate quite different specific series; different processes can generate similar series (Starbuck, 2006: 25–26).

Citations to The Fifth Discipline rose very linearly: the annual increases in citations were nearly constant from 1993 to 2005. Uses of the phrase learning organization were somewhat less linear in that the annual increases in citations grew larger over time, approximately doubling over ten years. Mainly linear growth might reflect a gradual opening up of multiple new markets, and this interpretation is consistent with some of the shifting currents in the kinds of people who have cited The Fifth Discipline. All the earliest citations came from documents in the English language, and as time passed citations appeared in more and more languages. Loosely, one could say that the languages migrated from developed economies toward developing economies. There have also been adoption currents related to occupational groupings. For example, many citations have come from documents written by US Naval personnel and very few citations have come from documents written by other military personnel. Nurses have also shown special interest in The Fifth Discipline. Although each of these occupational groupings probably did engage in some bandwagon adoptions, each occupational grouping adopted TLO rather separately. With little contagion across groupings, exponential growth was restrained by boundaries between occupations, societies, and languages.

There is no clear reason why six sigma and balanced scorecard began spreading rapidly around 2000. Both ideas had been latent in the business culture for several decades, and although there were triggering events that brought them to the forefront, such triggering events could have happened much earlier or much later. The idea that businesses should consider factors other than financial ones originated in France in the early twentieth century, and General Electric developed a multidimensional assessment system for its profit centers during the 1950s. A 1992 article in Harvard Business Review gave balanced scorecard new visibility, but Harvard Business Review publicizes many ideas every year and 1992 was several years before the interest in balanced scorecard began to accelerate. Very high quality became a popular theme in Japan during the 1960s, and this theme spread worldwide during the 1970s when it appeared that Japanese companies were having remarkable success. During the 1960s, statistical studies of the PIMS database (Profit Impact of Market Strategy) indicated that high-quality products are often very profitable. Then, in the 1980s, Motorola Corporation combined long-standing ideas about how to raise quality into a formal training program that the corporation marketed under the ‘Six Sigma’ trademark. For Motorola’s corporate clients, six sigma offered easy implementation, quantitative measures of results, as well as some terminological pizzazz. However, Motorola’s marketing of six sigma began almost two decades before interest in the idea began to accelerate.

Organizational learning is different. It seems quite unlikely that this idea could have started to become very popular before 1990. Although academics had written about organizational learning as early as the late 1950s, such ideas did not migrate into the literature of business practitioners. The phrase ‘organizational learning’ did not appear in Harvard Business Review until 1989 and it appeared in Sloan Management Review only once before 1991.

Senge’s TLO is a poor candidate for exponential growth based on imitation. Imitation of managerial ideas is more likely if the ideas are easy to comprehend, quick to implement, and capable of producing visible results. Senge’s ideas are sufficiently abstract that many people do not see their value and they are difficult and expensive to implement (Smith, 2008). Senge provides no simple prescriptions, and he advocates long-term, persistent commitment to unusual social processes. The benefits of TLO are elusive; there is no way to find out what would have happened in the absence of TLO. Thomas and Allen (2006) pointed to a lack of clear connection between learning and business success, and Smith said that some converts to TLO eventually shifted to other approaches after evidence of business success with TLO was not forthcoming.

The Fifth Discipline may continue to attract audiences less because it provides easy solutions than because it addresses challenging issues of current relevance. The book deals with management issues that have been becoming more and more relevant in affluent, developed economies during the late twentieth century. These issues seem likely to continue to gain relevance over the coming decades.

Senge wrote about a complex world, with many interdependencies—oligopolistic markets, corporations and governments that cooperate, externalities. The populace of this world does not have to scrabble around for existence and they aspire to do more than merely adapt to their environments; they reflect on their motives and actions and they seek to construct worlds with properties they desire. Workers are not lonely farmers at the mercy of weather or factory workers keeping pace with conveyor belts; they cooperate in teams, exchange ideas, analyze, and strategize.

Through the twentieth century, agriculture and manufacturing migrated toward developing economies, while the developed economies have shifted toward services. In the developed economies, the fastest-growing occupations have included professional and technical workers and managers. The US provides an extreme case. By 1990, the information sector accounted for three-fourths of US GNP, and over half of US workers were doing some type of information work.

Business in developed economies has been changing conceptually. New kinds of knowledge-intense and information-intense organizations have emerged that are devoted entirely to the production, processing, and distribution of information (Starbuck, 1992). These new kinds of organizations already employ many millions of people, with the Internet supporting new business and career opportunities. As well, facilitated by better telecommunications, business firms have been creating alliances and forming networks, and these larger entities have given business strategists license to think more about constructing environments that they desire instead of adapting to environments that already exist. Current thinking about strategic management emphasizes the usefulness of valuable resources that are rare and difficult to imitate (Barney, 1991), and many organizations seek to accumulate valuable and proprietary knowledge that they can exploit strategically. For instance, chemical and pharmaceutical companies employ skilled scientists and spend heavily on research aimed at developing proprietary products. Some manufacturing firms see experienced and highly trained managers as key assets, and many firms have appointed ‘learning officers’ who are charged with identifying useful knowledge and disseminating it to personnel who can use it. Managements have shifted focus from a more traditional input-and-output analysis to dealing with knowledge capital, information systems, logistics, and supply chains.

Senge saw these trends and responded to them, and it is unclear what forces might deflect changes from following the trends. It seems likely that information and knowledge will grow more and more important in developed economies. In particular, despite the fact that computers and electronic communications devices have existed for decades and they have become quite prevalent in Europe, Japan, and North America, only a fraction of the world population has use of computers, e-mail, or the Internet. At the same time, technological development has been accelerating. Organizations have been gaining access to more data more quickly. As this creates opportunities for surveillance from afar, competitive intelligence has been becoming easier and more productive, supervisors can more easily monitor distant subordinates, and organizations can more easily monitor their alliance partners. The technology also gives organizations more freedom to spread geographically, and they can collaborate effectively without actually merging.