Psychology has offered multiple insights into the vagaries of human learning. The literature has also enriched our understanding of organizational learning, while at the same time opening channels for scholarly debate. For example, questions have been raised about positivist as opposed to constructivist perspectives and the role of context versus personal determinism. To what extent are these considerations taken into account where the focus is the organization rather than the individual? Another point is whether there are missing strands that deserve closer scrutiny, given the emphasis on cognitive processes and what may be broadly termed ‘relational’ factors. We take an overarching approach as we address these questions, bringing together key themes, in line with the suggestion in the last edition of this Handbook that the paradigmatic shift in psychology is in this direction (DeFillippi and Ornstein, 2003).

The purpose of this chapter, then, is to explore how psychological learning theories have been used in the development of theories about organizational learning. We do so by means of a comparative framework (or typology) which allows us to compare and contrast significant themes along defined parameters. Utilizing a four-quadrant typology (Shipton, 2006) we first explore key aspects of individual learning theory and then turn to theories connected with organizational learning, in particular, those which are either drawn from, or have strong parallels with, psychological traditions. This way of assessing the various literatures offers a structure for comparing theoretical perspectives across levels of analysis (for example, individual, team, and organization), while also taking into account different paradigms. Some scholars, for example, view learning as amenable to control and direction, while others insist that learning rather unfolds naturally in the workplace. Our quest is to identify the main areas where various psychological paradigms have influenced organizational learning given these identified themes.

The advantages of using a typology have been described in detail elsewhere (Shipton, 2006). In short, a typology can subdivide the literature in order to ‘transform the complexity of apparently eclectic congeries of diverse cases into well-ordered sets of a few rather homogenous types, clearly situated in a property space of a few important dimensions’ (Bailey, 1994: 33). Each comparative type is relatively independent of the other, the important point being that there is a basis for comparison across types. Overall, the cataloging system offers the opportunity to draw conclusions linked with the profiling parameters that have been pre-defined (Bailey, 1994).

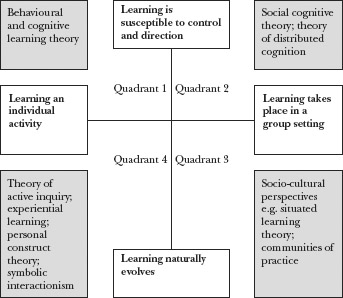

With these points in mind, a typology has been devised to categorize (as far as possible) individual learning research using a comparative matrix (see Figure 4.1). Along one continuum, we depict perspectives that focus on how learning may be managed, controlled or directed. The contrast is with (relatively) more explanatory or descriptive orientations, where learning is conceptualized as a process implicit in day-to-day tasks. Along the other continuum we examine the level of analysis; do authors focus on the individual or are they rather concerned about the wider context within which work activities take place? In considering these themes, we make reference to organizational learning literature. Here, there are again contrasting schools of thought not dissimilar from those highlighted above; on the one hand, there are studies where the orientation tends to be either prescriptive or normative. In a contrasting line of thought, scholars have been pre-occupied with how learning takes place in situ. Regarding levels of analysis, just as in the individual learning literature there is a distinction between an emphasis on the individual as opposed to the wider environment, where exploring organizational learning, perspectives tend to fall into one of two categories: those that adopt a micro perspective, where the focal point of interest is the individual and the surrounding work group or team, as opposed to those that are pre-occupied with organizational-level factors, tending towards a macro orientation.

Figure 4.1 The Four Quadrant Framework

We reviewed approximately eighty books and journal articles in developing our ideas, having been guided in our reading by a number of principles. Firstly, we looked for seminal studies that have been widely cited and were published in world-leading journals such as the Academy of Management Review, Academy of Management Journal, Organization Science, Human Relations, Organization Studies, and the Journal of Management Studies. We next supplemented the preceding search by examining more practitioner-oriented books and journals which have also significantly influenced thinking in this area (e.g. Argyris, 1990; Pedler, Burgoyne, and Boydell, 1999; Senge, 1990). To complete the review, we looked at long-standing seminal texts, such as Kelly (1955), Dewey (1938), Mead (1938), and Bandura (1982) whose principles are enshrined in common knowledge and to whom frequent reference is made in standard academic texts on learning, training, and development (e.g. Blanchard and Thacker, 2010; Harrison, 2009; Mankin, 2009). In this way, we hope to illustrate general trends in line with the parameters defined above, without attempting to categorize each and every paper (a task that is clearly impossible within a short book chapter). What follows offers a rough classification of these literature sources, given that there may at times be ambivalence in terms of where within the framework a certain piece of work is positioned. We have attempted to highlight this ambiguity while simultaneously presenting a reasonably consistent depiction of the framework itself.