We examine the received research on organizational knowledge structures with a special focus on their link to innovation. We note that the literature has used the term knowledge structure to represent three quite distinct components of organizational knowledge: the cognitive templates used by management, the content knowledge of the organization, and the transactive systems used by an organization to organize its knowledge. We use the term organizational knowledge-base as an abstraction to capture the aggregative entity that includes these three components. We then examine the research to identify six primary dimensions along which organizational knowledge-bases differ: size, content, veridicality, degree of differentiation, degree of integration, and embeddedness. We identify the three common mechanisms by which organizations search for innovations, recombinant, cognitive, and experiential search and examine the implications of the knowledge-base dimensions in the context of these mechanisms. This discussion also helps to locate derived dimensions of organizational knowledge-bases such as relatedness, decomposability, and malleability. We then review the organizational antecedents that shape organizational knowledge-bases and conclude with some thoughts on key areas of future research in this literature.

If only HP knew what HP knows—

Lew Platt, HP CEO (in Sieloff, 1999)

A dramatic growth in organizational knowledge over the past few decades has made the problem of developing appropriate structures for capturing and storing knowledge in organizations especially salient. Concomitant with this growth in organizational knowledge and increased need for knowledge structuring, intensifying competition and high rates of technological obsolescence have created a need for greater and faster innovation in many industries. Addressing the challenges posed by these two problems, of structuring knowledge and managing it for innovation, are key tasks for organization theorists in the knowledge economy. Surveying and structuring the emergent literature in these domains, and thus cumulating our understanding of the relationship between knowledge structures and innovation, is the key objective of this chapter. Additionally, marking the current state of knowledge in this area is useful for identifying key problems and challenges that remain unaddressed and, therefore, for highlighting the gaps in our current understanding of these problems.

The organizational literature has defined and represented knowledge structures in several different ways, sometimes with slightly different meanings. Commonly, knowledge structures have been conceived of as cognitive templates. For instance, at the individual (rather than organizational) level Walsh (1995) suggests ‘A knowledge structure is a mental template that individuals impose on an information environment to give it form and meaning.’ Similarly, at the organizational level Lyles and Shwenk (1992) suggest that ‘knowledge structure refers to shared beliefs at the organizational level. Further, these beliefs have a structure.’ As they elaborate, ‘the concept of knowledge structures deals with goals, cause-and-effect beliefs, and other cognitive elements.’ Further, in their conceptualization, knowledge structures are characterized by some core features which remain invariant over long periods of time and some peripheral features which change (Lyles and Schwenk, 1992). Core features refer to the set of ‘beliefs and goals on which there is widespread agreement,’ while peripheral elements include knowledge about sub-goals and about the behavior or steps necessary to achieve the goals specified in the core set. Peripheral knowledge is open to much more debate and disagreement within the organization (Lyles and Schwenk, 1992). Similarly, in describing dominant logic, Prahalad and Bettis (1986) refer to knowledge systems, beliefs, theories, and propositions that have developed over time based on the manager’s personal experiences. In other words, the term ‘knowledge structures,’ as emphasized by Galambos et al. (1986), has often referred to the cognitive structure underlying top-down or theory-driven information processing.

However, other authors (e.g. Walsh, 1995) have noted that organizational knowledge per se, includes not just process knowledge such as cognitive filters and beliefs, shared perspectives, and mental maps, but also content knowledge that includes information about (for instance) technological, production, and marketing concepts and relationships (e.g. see Yayavaram and Ahuja, 2008). Thus, knowledge about manufacturing of semiconductors, the properties of various types of integrated circuits, and the payment history of various customers are all parts of the content knowledge of a semiconductor manufacturer.

Finally, a third set of authors have drawn attention to another component of organizational knowledge—the set of procedures or transactive systems that are used by the organization for encoding, storing, retrieving, updating, and communicating organizational knowledge (Hollingshead, 2001; Wegner 1986; Lewis, Lange, and Gillis, 2005). Thus, who knows what, where specific pieces of knowledge are stored in the organization, and how they are to be retrieved are the kinds of knowledge stored in the transactive systems of an organization.

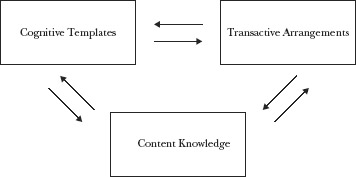

Clearly, any attempt to understand the implications of an organization’s knowledge structures for innovation should encompass an analysis of not just organizational knowledge about beliefs, goals, and cognitive templates but also the organization of the substantive, task related content knowledge held by the organization as well as the transactive systems used by the organization to maintain, grow, and utilize its knowledge (see Figure 25.1). Accordingly, to facilitate our analysis of knowledge structures we synthesize the above notions of cognitive, content, and transactive knowledge in an organization to introduce the notion of an organizational knowledge base.b

Figure 25.1 Organizational Knowledge-Base

We will use the concept of an organizational knowledge-base as a key organizing construct for this review. In its simplest sense an organizational knowledge-base refers to ‘what an organization knows.’ It is in essence a summation of the knowledge contained in the organization. Such knowledge may consist of ‘content’ knowledge about technologies, markets, products, customers, routines, or ‘cognitive’ knowledge such as beliefs, templates, cognitive frames, and heuristics or ‘transactive’ knowledge about how to access or update content knowledge. The organizational knowledge-base may reside in electronic or physical media, but also organization members, procedures, routines, and organizational structures. Knowledge-bases can be distinguished from ordinary databases in two ways. First, while databases are simply logical, structured classifications of data into logical categories and can be used to systematize, enhance, and expedite large scale intra- and inter-firm knowledge management (Alavi and Leidner, 2001), knowledge-bases also include conceptual maps that outline the interdependencies across contents, and include interpretations and beliefs about the data, as well as routines and rules for the storage, maintenance, and retrieval of the data themselves. Second, following from this, databases have usually an electronic or a physical manifestation. Knowledge-bases may however reside in people, relationships, organizational structures, and routines. Thus, all databases will be a part of a knowledge-base but a knowledge-base may not be captured entirely in databases.

The organizational knowledge-base construct is also related to, but distinct from, the construct of organizational memory (see Walsh and Ungson, 1991). As defined by Walsh and Ungson, the construct of organizational memory refers to ‘stored information about a decision stimulus and response that when retrieved, comes to bear on present decisions.’ Thus, organizational memory is derived from an organization’s past experience and includes knowledge that is retained and recalled in the context of a specific decision stimulus. An organizational knowledge-base however has a broader scope of covered knowledge—it includes elements of knowledge that have not necessarily emerged from the organization’s past experience or are not related to or recalled in the context of specific decision stimuli.

Note that the relationship between the three components of the organizational knowledge-base is likely to be bidirectional within each dyad. A management’s cognitive template is likely to influence both the nature of content knowledge the organization accumulates and the kind of transactive systems it puts in place. In turn though, the content knowledge accumulated by an organization is likely to influence the cognitive templates of the management as well as the type of transactive systems it uses. Finally, the nature of transactive systems themselves may influence the content of a knowledge-base as well as the cognitive templates of the management.