Knowledge assets such as technical and organizational know-how undergird each firm’s competitive position. Such assets are partially embedded in routines, the well-established and largely uncodified patterns that firms have developed for finding solutions to particular problems. Learning, which is necessary for the maintenance and development of these assets, is an inherently collective, organizational process that is grounded in, but surpasses, the experience and expertise of individuals (Fiol and Lyles, 1985; Simon, 1991) and individual competence. Ideally, this collective learning permits the organization to transcend individual-level bounded rationality (Teece et al., 1994). Value can also derive from the unique combination and alignment of intangible assets that entrepreneurs and managers assemble.

The pioneering description of organizational learning in Cyert and March (1963) saw learning as crisis driven and short term in focus, and inflexible to managerial intent. But for the field of strategic management, the key insight from Cyert and March was that the adaptive (and often path dependent) learning of firms, as embodied in their standard operating procedures, accounts for firm heterogeneity (Pierce et al., 2002). This notion, coupled with the insights of Penrose (1959) about the role of firm ‘resources’ in growth and innovation, eventually gave rise to the RBV of the firm. Over time, the dynamic capabilities framework (Teece et al., 1997) emerged as the dominant RBV-rooted approach to strategy.

In the dynamic capabilities framework, organizational learning (which is in part dependent on the orchestration talents of top management) is at the heart of a firm’s capabilities. Effective organizational learning (and its associated value creation and capture) requires dynamic capabilities, and vice versa (Easterby-Smith and Prieto, 2008).

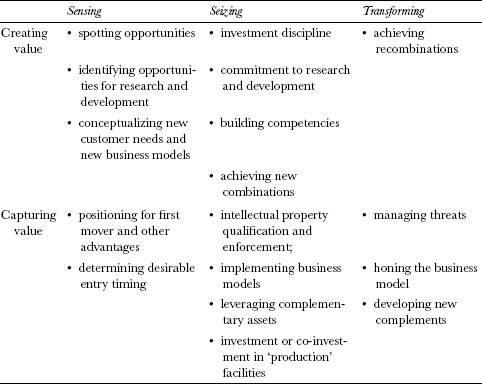

This section reviews the nature of firm resources and then outlines the dynamic capabilities framework. Dynamic capabilities can usefully be thought of in three clusters: sensing opportunities (building new knowledge), seizing these opportunities to capture value, and transforming the organization as needed to adapt to the requirements of new business models and the competitive environment.

Resources/competences

The core building blocks of stable and growing organizations are resources. Resources are firm-specific (generally intangible) assets that are difficult, or impossible, to imitate. Intangible assets are usually quite differentiated. They are stocks rather than flows.

Firm-specific assets are idiosyncratic in nature, and are difficult to trade because their property rights are likely to have fuzzy boundaries and their value is context dependent. As a result, there is unlikely to be a well-developed market for resources/competences; in fact, they are typically not traded at all. They are also generally difficult to transfer amongst firms. Examples include process know-how, customer relationships, and the knowledge possessed by groups of especially skilled employees.1

Competences are a particular kind of organizational resource. They result from activities that are performed repetitively, or quasi-repetitively. Organizational competences enable economic tasks to be performed that require collective effort. They are usually underpinned by organizational processes/routines. Indeed, they represent distinct bundles of organizational routines and problem-solving skills.2

In short, ordinary competence defines sufficiency in performance of a delineated organizational task. It’s about doing things well enough, or possibly very well, without attention to whether the economic activity is the right thing to do. Competences can be quantified because they can be measured against particular (unchanging) task requirements. The level of a competence can be benchmarked; the assessment of a competence does not require that the activity be aligned with the firm’s environment and other assets/competences.

Some processes undergirding competence are formal, others informal. As employees address recurrent tasks, processes become defined. The nature of processes is that they are not meant to change (until they have to). Valuable differentiating processes may include those that define how decisions are made, how customer needs are assessed, and how quality is maintained. Organizational learning in these cases may evolve toward formal rules or remain as heuristics.3

As an organization grows, its capabilities are embedded in competences/resources and shaped by (organizational) values. Organizational values define the implicit norms and rules of the organization. They determine how it sets priorities with respect to how employees and affiliates work together.

While economics has often modeled firms as homogeneous, or asymmetric only in their access to information, the ‘resource-based view’ of the firm recognizes the unique attributes of individual firms. In the 1980s, a number of strategic management scholars, including Rumelt (1984), Teece (1980, 1982, 1984), and Wernerfelt (1984) began theorizing that a firm earns rents from leveraging its unique resources, which are difficult to monetize directly via transactions in intermediate markets.

As mentioned earlier, value can derive not only from routines but also from unique combinations of highly differentiated intangible assets. Such assets are traded only occasionally, if at all. Put differently, the markets on which they are bought and sold are very ‘thin.’ The ownership and orchestration of non-tradable (intangible) assets can therefore be a basis for long-term profitability in what we normally think of as competitive (final product) markets.

The Internet and the explosion of markets for everything have vastly expanded the number and type of goods and services that are readily accessed externally (Teece, 2000). As more and more activities become available from suppliers, the range of domains (thin markets) in which competitive advantage can be built narrows.

One class of very thin markets is the markets for intangibles. Intangible assets remain especially difficult—although not impossible—to trade. This is particularly true for knowledge assets and, more generally, ‘relationship’ (e.g. customer or supplier) assets. Knowledge assets are tacit to varying degrees and are both difficult to trade and costly to transfer (Teece, 1981a, 2000). So are relationship assets. Because the market for intangibles is thin and riddled with imperfections, this favors internalization (vertical or lateral integration) of the mechanics of capturing strategic value. Certain assets are more valuable to one firm than another, and because markets are thin, such assets, if procurable, can often be bought on the cheap.

Dynamic capabilities

‘Resources’ such as intangible assets suggest stocks, not flows. However, for long-term competitive advantage, resources must be constantly renewed (Teece, 2009). The logic of renewal is amplified in fast-moving environments such as those characteristic of high-tech sectors (e.g. computers). However, a need to renew resources can also occur in ‘low-tech’ industries (e.g. home construction).

A framework is needed to help explain how business enterprises build and then renew their resource base, keeping it aligned with what’s needed to serve customers and meet or beat the competition. The framework we offer is called dynamic capabilities.

Dynamic capabilities are the firm’s ability to integrate, build, and reconfigure internal and external resources/competences to address and shape rapidly changing business environments (Teece et al., 1990, 1997; Teece, 2007a). They determine the speed at, and degree to which, the firm’s idiosyncratic resources/competences can be aligned and realigned to match the opportunities and requirements of the business environment. The goal is to generate sustained abnormal (positive) returns.

Dynamic capabilities may sometimes be rooted in certain change routines (e.g. product development along a known trajectory) and analysis (e.g. of investment choices). However, they are more commonly rooted in creative managerial and entrepreneurial acts (e.g. pioneering new markets). Nevertheless, the learning that takes place in the dynamic capabilities framework is inherently collective, requiring coordinated search and communication in order to be effective (Pierce et al., 2002).

The essence of resources/competences as well as dynamic capabilities is that they cannot generally be bought; they must be built. As noted above, dynamic capabilities measure the capacity to build new intangibles when necessary and to align and realign, integrate and reintegrate such intangibles so that they are tuned to the business environment. Sensing, seizing, and transforming are meta-level categories of such attributes (opportunity seizing and adjustment mechanisms). Firms with these attributes can evolve and co-evolve with the business environment. Such capabilities create the potential for long-term profitability because markets do not price most resources/intangible assets at their real value to the buyer when the buyer possesses scarce complementary and, especially, co-specialized assets (Teece, 2007b). However, the required resources/intangible assets may not yet exist. They must first be built or created. In these situations, the business enterprise can create a distinctive competitive advantage by building the assets ahead of its competitors.

The sensing and seizing categories in the dynamic capabilities framework are similar to two activities discussed in the management literature as potentially incompatible within a single organization: exploration and exploitation (March, 1991). Exploration (e.g. research on a potentially disruptive technology) has a longer time horizon and greater uncertainty than exploitation (e.g. selling mature products). The two types of activities require different management styles; one solution is an ‘ambidextrous organization’ where two separate subunits with different cultures are linked by shared company-wide values and senior managers with a broad view—and appropriate incentives (O’Reilly and Tushman, 2004; O’Reilly et al., 2009).

As discussed above, a firm’s basic competences, if well honed, enable it to perform its current activities efficiently. However, whether the enterprise is at present making the right products and addressing the right market segment, or whether its future plans are appropriately matched to consumer needs and technological and competitive opportunities, is determined by dynamic capabilities. Dynamic capabilities, in turn, require the organization (especially its top management) to develop conjectures, to validate them, and to realign assets and competences for new requirements. They enable the enterprise to profitably orchestrate its resources, competences, and other assets in order to take account of changing market and technological circumstances.

Dynamic capabilities are also used to assess when and how the enterprise is to ally with other enterprises. The expansion of trade has enabled and required greater global specialization. To make the global system of vertical specialization and co-specialization (bilateral dependence) work, there is a need (indeed an enhanced need) for firms to develop and align assets and to combine the various elements of the global value chain so as to develop and deliver a joint ‘solution’ that customers value.4

There is another realm in which dynamic capabilities are especially salient. Not infrequently, an innovating firm will be required to create a market, such as when an entirely new product is offered to customers, or when new intermediate products must be traded. Dynamic capabilities, particularly the more entrepreneurial competences, are a critical input to the market creating (and co-creating) processes.5

To summarize, dynamic capabilities reflect the capacity a firm has to orchestrate activities and resources/assets within the system of global specialization and co-specialization. They also reflect the firm’s efforts to create/shape the market in ways that enable value to be created and captured. Dynamic capabilities require change routines and more. Fast-moving environments require modifying, or, if necessary, a complete revamping of what the enterprise is doing so as to maintain a good fit with (and sometimes to transform) the ecosystem and markets that the enterprise occupies. Some of this change management can be routinized. Some cannot.6 Microfoundations and organizing principles have been laid out elsewhere (Teece, 2007a). The following is a brief overview of the major dynamic capability categories.

The continuous renewal enabled by dynamic capabilities requires an ongoing set of activities and adjustments that can be divided into three clusters: (1) identification and assessment of an opportunity (sensing), (2) mobilization of resources to address an opportunity and to capture value from doing so (seizing), and (3) regular realignment (transforming). These activities are required if the firm is to sustain itself as markets and technologies change, although some firms will be stronger than others at some or all of these.

One could imagine that a market economy would allow individuals and organizations to specialize in one of the three capability clusters. However, the markets for opportunities, inventions, and know-how are riddled with inefficiencies and high transaction costs, and most entrepreneurs are forced to bundle these activities together (i.e. do all three).7

The relative importance of the competences and adjustment mechanisms that constitute sensing, seizing, and transforming varies according to circumstance. To simplify the analysis of dynamic capabilities even further, they can be grouped into two essential classes of activities: creating value and capturing value (see Table 23.1).

Table 23.1 Activities conducted to create and capture value (organized by clusters of dynamic capabilities)

Dynamic capabilities are most relevant in a regime of rapid change, a condition that prevails in a growing number of industries. The global economy has undergone drastic changes that have accelerated the rhythm at which firms innovate. The decreased cost of communication and data flow, the reduced barriers to trade, and the liberalization of labor and financial markets in many parts of the world are forcing firms to confront agile and/or low-cost competitors early in life. This in turn has caused firms to undertake a major revision of their innovation strategies, such as a greater reliance on open innovation, which changes how firms must learn and ‘store’ new knowledge.8