The Role of Web 2.0 Technologies in Support of Organizational Knowledge Management

Web 2.0 is the business revolution in the computer industry caused by the move to the internet as platform, and an attempt to understand the rules for success on that new platform. Chief among those rules is this: Build applications that harness network effects to get better the more people use them.

(O’Reilly, 2006)

Coined by Tim O’Reilly (2005), the term Web 2.0 refers to applications that facilitate interactive information sharing, interoperatibility, and collaboration on the World Wide Web (Wikipedia.org). Web 2.0 has also been defined as ‘the philosophy of mutually maximizing collective intelligence and added value for each participant by formalized and dynamic information sharing and creation’ (Hoegg, Martignoni, Meckel, and Stanoevska-Slabeva, 2006: 13). Each of these definitions focuses more on participation than technology. The linkage between knowledge management and Web 2.0 can be seen in the shift from process and stand-alone systems to network and collaboration.

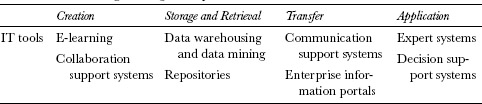

A decade ago, we could identify specific types of systems that were designed to support individual knowledge processes. Knowledge management systems (KMS) can have core functionality that supports the coding and sharing of documents in repositories, the development of knowledge directories, and the creation of knowledge networks (Alavi and Leidner, 2001). Reflecting the four knowledge processes, Alavi and Tiwana (2003) specified ITs supporting them in Table 6.1.

Table 6.1 Knowledge management processes

McAfee (2006) described knowledge management-supporting IT at the time as being comprised of channels and platforms. Channels encompassed technologies including e-mail and instant-messaging, where the audience was small or unique and the distribution of knowledge was limited. Platforms encompassed intranets or enterprise portals, and while the knowledge was highly visible and shared, it was generally created by a small group of gatekeepers. Channels were generally used more than platforms (Davenport, 2005). In addition, there has been an evolution away from static integrative IT artifacts, such as document management systems, expert systems, and workflow systems, to dynamic interactive IT artifacts, such as social networking tools, blogs, and wikis (Hayes, 2011). Today, elements of Web 2.0 technologies span the four knowledge processes and encompass the power of communities and networks.

In a Delphi study of KMS requirements, Nevo and Chan (2007) identified desirable capabilities, based upon the four knowledge management processes. First, incorporation of appropriate incentives for knowledge contribution is desirable for creation. Second, storage and retrieval should include multimedia capabilities, content management functionality, and a central repository, and enable easy and fast access to knowledge. Third, transfer and sharing should also include multimedia, report generation, and presentation functionality, and enable collaboration and knowledge sharing. Finally, a customizable interface and a ‘push’ strategy for knowledge were desirable for knowledge application. These ideal KMS capabilities mirror those available through many Web 2.0 technologies, which we will explore in the remainder of this chapter.

A common characteristic of all Web 2.0 platforms is their dynamic content, networked structure, and online edits, compared to static content, hierarchical structure, and controlled change of earlier Web content. A challenge in traditional KMS is the lack of social context surrounding both the content and individuals providing or seeking it (Parise, 2009). In contrast, Web 2.0 technologies support knowledge management by interlinking the conversations that sustain communities through user-friendly technological tools (Kosonen and Kianto, 2009). Levy (2009) compared Web 2.0 and KM principals, finding a high degree of correlation between the two. Platform orientation, value of networks, services development, individual participation, collective knowledge, and content as core are all principles that apply in both domains.

We have chosen to highlight two of the most prominent concepts of Web 2.0 as they relate to knowledge management in order to structure this chapter. One of the core concepts of Web 2.0 espoused by O’Reilly (2006) is that data is the new ‘Intel Inside,’ indicating that the value resides in content rather than structure or infrastructure. Reflecting the value of content over form, Web 2.0 tools are generally easy-to-use, lightweight, and primarily open-source, lowering barriers-to-entry to participation (Parameswaran and Whinston, 2007). A second core concept noted in the definition (O’Reilly, 2006), is to leverage network effects.

While all Web 2.0 tools support both concepts by definition, we have grouped several tools into categories, depending on whether they are platforms that support one concept more than the other. The first category we term content publication platforms, where the content is supported by the social network, capturing tools such as blogs, multimedia aggregators, and wikis. The second category we term social media platforms, where the social network is supported by content, including social tagging, synthetic worlds, and social networking software. The term ‘platforms’ is specifically used, reflecting the goal of Web 2.0 to view the Internet as a platform and differentiating them from point-to-point channels.

Content publication platforms

We define content publication platforms as Web 2.0 tools whose primary characteristic is adherence to the principle of data being the next ‘Intel Inside.’ Networks’ effects are key components to their success; however, the content and the structuring of interaction around it place the network in an enabling role. In this section, we look briefly at two content publication platforms—blogs and multimedia content sites—before examining wikis in greater detail.

Weblogs, or blogs, are personally authored web pages in reverse chronological order, using specialized blogging software to simplify the publication task for end users (Wagner and Bolloju, 2005). As blogs are chronological, the content is rarely edited and simply accretes, often with critical content being referenced or brought-forward to be reinforced. A wide range of open-source software, primarily PHP or Perl-based, is available to support blogs, as are many blog websites, such as Blogger, Wordpress, or LiveJournal. Blogs tend to be authored by single users and hence often will present the personal view of the author (Wagner and Majchrzak, 2006). Specific types of blogs can include personal journals, commentaries on other websites, and knowledge logs (Herring, Scheidt, Bonus, and Wright, 2004). In its aggregate form, the proliferation of blogs is known as the blogosphere, which expanded rapidly in the early 2000s (Kumar, Novak, Raghavan, and Tomkins, 2004).

Blogs have been identified as supporting both knowledge processes and communities. Following Nonaka, Toyama, and Konno’s (2000) work on the concept of ba, Martin-Niemi and Greatbanks (2010) suggest that the blogosphere acts as a knowledge creation space. As blogs are also storage mechanisms for individuals’ knowledge, Wagner and Bolloju (2005) suggest that they can be ‘harvested’ for innovation communities, linking this Web 2.0 tool to the knowledge storage and retrieval process. Firms such as IBM have demonstrated how blogs can be used to encourage employees to share their knowledge (Razmerita, Kirchner, and Sudzina, 2009). Recognition as an expert and its consequent generation of social capital is a key component in developing these knowledge sharing communities (Huysman and Wulf, 2006). Blogs have been suggested as a component of decentralized, informal knowledge management that can, with appropriate metadata, be navigated and their knowledge retrieved (Cayzer, 2004). Finally, as the blogosphere can be navigated through interest-based linkages between blogs (Kumar et al., 2004), it can be seen as developing and supporting networks of practice.

While blogs and wikis can be viewed as conversational technologies supporting knowledge management through the written word (Wagner and Bolloju, 2005), there are other Web 2.0 tools supporting a range of other media types. A core application for these tools is podcasting, which enables the sharing of audio and video on a range of devices. The term ‘podcasting’ comes from a fusion of the ubiquitous Apple iPod with broadcasting (Crofts, Dilley, Fox, Retsema, and Williams, 2005). The technology allows the user to decouple the content from the producer’s channel and gain more control over the media, allowing for a proliferation of content sources through multiple channels. Many specialized websites—multimedia aggregators—support this proliferation of media, including YouTube.com for video, Last.fm for music, and Flickr.com for pictures.

Multimedia aggregators have an important role to play in knowledge management of non-textual information. With many contributors throughout the world, YouTube has been effective in sharing knowledge without constraints of censorship, such as political speeches being posted, commented on, taken down, and reposted providing a forum for public discourse (Parameswaran and Whinston, 2007). Podcasts are an effective mechanism for transferring knowledge in the form of the spoken word, which previously had been confined to its point of origin or tightly controlled channels (Crofts, Dilley, Fox, Retsema, and Williams, 2005). As a repository for non-textual information, with proper metadata, these sites support oral and visual capture of content and support knowledge storage and retrieval processes. Finally, multimedia content sites are more than mere storage as they create communities through the tagging of media, the following of key contributors, and the generation of comments.

Content in blogs and multimedia aggregators is contributed individually and, in spite of comments by others, remains the unique contribution of the author. In contrast, wikis are content publication platforms that form a collaborative contribution of the community.

Wikis Wiki is the Hawaiian word for ‘quick’ or ‘fast.’ When Ward Cunningham invented the first wiki in 1995, his intent was to publish information rapidly and collaboratively on the Internet in a form that was the simplest online database that could possibly work. Leuf and Cunningham (2001) defined a wiki as ‘a freely expandable collection of interlinked Web pages, a hypertext system for storing and modifying information—a database where each page is easily editable by any user with a forms-capable Web browser client’ (2001: 14). Characteristics of wikis include their collective authorship, instant publication, extent of versioning, and simplicity of authorship (Prasarnphanich and Wagner, 2009). In contrast to the one-to-many monologue form of most blogs, wikis exhibit a many-to-many dialogue form, where participation is more equal (Wagner and Bolloju, 2005).

Stemming from these characteristics, the advantages of wikis include their ease of use, ability to act as a central repository of information, tracking and revision features, encouragement of collaboration between organizations, potential to solve the issue of information overload by e-mail, and development of a trusting culture (Grace, 2009). As they represent the collective knowledge of a community, wikis are suitable for maintaining best practices within the community (Wagner and Bolloju, 2005). Given wikis’ open and dynamic nature, the key success factor in wiki adoption for firms appears to be a corporate culture that values collaboration, is less hierarchical, and recognizes innovation (Wagner and Majchrzak, 2006).

In comparison to the chronological nature of blogs, wikis are organized by topic. Therefore, unlike blogs which append material to older contributions or comment on those contributions, contributions to wikis are added directly to the existing body of knowledge. One of the concerns with wikis is their inherent openness, so trust is vital within a wiki community (Raman, 2006). Reflecting this openness and need for trust, wikis have been described both as a technology and the social norms that surround its use (Prasarnphanich and Wagner, 2009). Functionally, anyone can create a new wiki page, add or edit content in an existing wiki page, and delete content within a page, without any prior knowledge or skills in editing and publishing on the Web (Raman, 2006). This technical format requires a supporting social system, which can be described as wiki-etiquette or ‘the Wiki way’ (Prasarnphanich and Wagner, 2009). These social norms and supporting social system are key components to the network of practice enabled by the wiki.

An example of the ‘wiki way’ taking hold in a company can be found in IBM, where more than 2000 internal wikis are created and maintained by over 20,000 employees (Wagner and Majchrzak, 2006). The introduction of wikis was not planned, as they were often user initiated without the knowledge of IT management, but were embraced by the company. There appeared to be recognition that the communities and networks of practice that were supported by wikis were a valuable asset to the firm. The use of wikis is now well established at IBM, as individuals previously on wiki-enabled projects initiate wikis on their new projects. This degree of use has been made practical by the implementation of a wiki-appliance that creates a new wiki with a single click.

One of the key applications of wikis in IBM is in developer networks (Wagner and Majchrzak, 2006). Two critical problems with documentation reported by IBM include an inability to locate it and the fact that it quickly becomes inaccurate. One senior manager noted that documentation located in a team repository in Lotus Notes or on a shared drive often gets forgotten, whereas a wiki can be quickly located. Similarly, documentation is frequently inaccurate and difficult to update; however, with a wiki it is possible for a developer to modify the contents if an inaccuracy is found. Wikis in this context support storage and retrieval of knowledge for IBM.

Another application is client-facing wikis, with the goal of creating customer communities. IBM has been a leader in creating policies for this application, guiding employees’ use of wikis with few unbreakable rules (such as non-disclosure of financials or unannounced product developments) and the aim to reflect IBM’s knowledge and skills while adding value for the customer. Working within these guidelines, the IBM staff is able to engage with clients in creating a collaborative environment for the creation and acquisition of new knowledge.

Wikis have been found to be successful in supporting a range of knowledge management processes. In a study of the use of a wiki to structure the learning environment of a course in knowledge management, students found that wikis improved collaboration and the quality of work and were effective tools for knowledge creation (Chu, 2008). Openly shared collaborative writing, as supported by wikis, has been identified as a new form of collaborative knowledge creation (Wagner and Bolloju, 2005), which is primarily due to the instant publication of new knowledge (Wagner and Majchrzak, 2006). Additionally, considering Nonaka’s (1994) SECI spiral, a wiki user can externalize his or her knowledge, see it instantly combined with other knowledge, and have it internalized by another wiki user, who can socialize it with his or her peers. Wagner and Bolloju (2005) identify that best practice communities can benefit from wikis, suggesting they are strongly related to the knowledge sharing process. This was supported in the knowledge management course study where students could read, amend, and comment on their peers’ work (Chu, 2008). Storage and retrieval processes are enabled by capturing the current document and all previous versions, and by the use of built-in search tools. Wiki structure of forward and backward links assists in retrieval as the wiki can be navigated from any start point (Wagner and Majchrzak, 2006).

Wikis are ideal Web 2.0 tools as they exemplify the leveraging of network effects of communities. The basis of the success of wikis as a tool for knowledge management can be found in Surowieki’s The Wisdom of Crowds (2004), where the consensus judgment of a large group of inexpert individuals (the crowd) can be superior to that of any individual member of the crowd or even an expert assessor. Supporting the network effects point of view, one study found that new articles tend to be written by different authors from the articles to which they are linked; hence the scalability of wikis is limited less by the capacity of individual contributors than by the size of the contributor pool (Spinellis and Louridas, 2008). Similarly, the age of a wiki is both an indicator and a contributing factor to its sustainability (Majchrzak, Wagner, and Yates, 2006). The longer a wiki exists, the more frequently it is accessed, both by lurkers and active participants, and hence the more likely it will be to continue.

Wikis are also exemplars of electronic networks of practice tools, as the underlying factors in the benefits generated from wikis are based primarily on the participants’ belief in, capacity of, and reliance on collaboration (Majchrzak et al., 2006). Collaborative motivations for wiki contribution appear to outweigh individualistic ones (Prasarnphanich and Wagner, 2009; Wasko and Faraj, 2000). Even so, there are strong individual benefits to be achieved by participation in corporate wikis that include: enhancing reputation, making work easier, and helping improve organizational processes (Majchrzak et al., 2006).

The combination of collaborative motivation and individual benefits makes for a resilient form of organizational knowledge management, particularly from the point of view of use and misuse. While open wikis have been subject to misrepresentation as a form of attack, internal corporate wikis or closed community-based ones are likely to have minimal malfeasance due to their more focused use (Denning, Horning, Parnas, and Weinstein, 2005).

Nonetheless, organizational wikis, as they often include proprietary corporate knowledge, have to balance between openness and access control to ensure that critical knowledge is protected (Wagner and Majchrzak, 2006).

Of the content publication platforms—blogs, multimedia aggregators, and wikis—the last may be the most reliant on network effects to be effective, but content is still the core. In the next section, we examine social media platforms, where the exploitation of network effects is paramount.

Social media platforms

We define social media platforms as Web 2.0 tools whose primary characteristic is the exploitation of network effects. It is not that content is unimportant, but rather that in this grouping it is the social network that is being supported by content. In this section, we look briefly at two social media platforms—social tagging and virtual worlds—before examining social networking software in more detail.

Collaborative or social tagging and bookmarking are mechanisms for communities to share bookmarks of Internet resources. Tags and bookmarks are individual metadata linked to a particular web-page, and as such are not content themselves but paths between content. Tags can be public or private, supporting either the collective or personal navigation of content. Traditional tagging requires users to apply a predefined set of hierarchical terms that often takes the form of a centrally defined taxonomy. In comparison, collaborative tagging allows individual users to tag content and create connections between pages that share something in common (Levy, 2009). A folksonomy is the term coined by Thomas Vander Wal to refer to this aggregation of tags, combining the concepts of people (folk) and taxonomy (Smith, 2004).

Tags reflect individual users’ schema of knowledge and the aggregation of this metadata is the main benefit of collaborative tagging to knowledge management. Similar to the convergence seen in wikis through the collective application of judgment, collaborative tagging systems also appear to converge on a stable distribution of tags (Halpin, Robu, and Shepherd, 2007), making them supportive of knowledge storage and retrieval processes. Also, social tagging is a mechanism that can support knowledge creation and acquisition, as it can identify knowledge that can either be combined with existing organizational knowledge to create something new or absorbed as knowledge that is ‘new’ to the organization. The navigation of the Web by tags supports networks of practice by combining and organizing the collective knowledge represented by individual community members.

While social tagging supports conceptual navigation of the Web, virtual worlds are conceived to support ‘physical’ navigation within worlds embedded in the Web. Synthetic or virtual worlds are three-dimensional graphically-intensive electronic environments where members assume a persona and engage in social and commercial interaction within a geographically dispersed community (Castronova, 2005). Interaction in virtual worlds is synchronous and three-dimensional, as users interact in real time and navigate the virtual world itself rather than web pages. While individuals can develop an image within the community based upon contributions to content publication and other social media platforms, image creation is direct in virtual worlds through the selection of self-presenting avatars and their directed interactions with others (Kaplan and Haenlein, 2009). Interest in virtual worlds by the business community has been primarily focused on marketing efforts within these synthetic environments (Hemp, 2006).

Virtual worlds can be used either to escape reality or to replicate it (Hemp, 2008), and it is in this latter use that their value to knowledge management can be seen. Synthetic worlds have the potential to assist in knowledge management through the development of collective knowledge and common understanding by addressing dispersion of participants (Burley, Savion, Peterson, Lotrecchiano, and Neshnavarz-Nia, 2010). Two of the key characteristics that help diminish the impact of distance are social presence and visualization (Ives and Junglas, 2008). Virtual worlds allow interaction including the social cues which are absent from other distance-spanning tools, providing context to knowledge sharing.

Through social tagging, networks of common interest can be discerned; through synthetic worlds, direct social interaction can take place and networks can be inferred. However, only through the use of social networking software can those social networks be made explicit and navigated.

Social networking software

Social networking sites (SNS) and their supporting software allow users to manage their contacts, share personal information, and socialize online. Boyd and Ellison (2008) define social networking sites as ‘web-based services that allow individuals to (1) construct a public or semi-public profile within a bounded system, (2) articulate a list of other users with whom they share a connection, and (3) view and traverse their list of connections and those made by others within the system’ (2008: 211). Sites can be oriented towards supporting friendships (Facebook.com), shared interests (MySpace.com), or professional relationships (LinkedIn.com), among other things. One of the key benefits of SNS is the generation and maintenance of social capital (Ellison, Steinfield, and Lampe, 2007). In keeping with the link to social capital, SNS are useful in the socialization of new organizational members, particularly if they already have a high degree of personal use (Leidner, Koch, and Gonzalez, 2010; Kane, Robinson-Combre, and Berge, 2010).

SNS first emerged in the late 1990s, with SixDegrees.com recognized as the first launched in 1997 to articulate and make visible social networks (Boyd and Ellison, 2008). The common core of SNS is their use of profiles and links between profiles, which map the social network. Users enter profiles that include personal and/or professional information and then identify other individuals registered with the site. Depending on the intent and culture of the site, these linkages can be termed ‘friends,’ ‘fans,’ ‘followers,’ ‘contacts,’ or other variations. The leveraging of network effects of SNS can be seen here in the value of the site being proportional to the number of users that can be connected. The utility of the networks is in a user’s ability to navigate their contacts’ links in order to discover new potential connections. To enable the development of social networks, SNS incorporate conversational mechanisms including commenting (public) and messaging (private) communications. Differentiation between SNS can be based upon network intent and audience, geographic or language specificity, or other methods of segmentation (Boyd and Ellison, 2008).

Military Bank (a pseudo name) is an organization in which social networking software plays an important role in the firm (Leidner et al., 2010). The 2500-employee IT department of the Military Bank was plagued with a sixty to seventy percent turnover rate in new hires during its second year of employment. As a mechanism of increasing retention of Generation Y hires faced with the tedious nature of their highly technical jobs, the organization deployed Nexus, a Web 2.0 platform to make the job more interesting. Nexus, based on SharePoint included features supporting both work and social interactions and was oriented towards the development of a community of practice of Generation Y IT personnel within the firm.

Nexus was seen by executive and middle managers as being responsible for decreased turnover, higher morale, and better engagement of employees (Leidner et al., 2010). In addition to the positive emotional responses of individuals, there were knowledge management-related benefits. Social networking tools facilitated establishing social and professional ties among new hires. These ties and emotional connections facilitated problem solving by providing an access to sources of knowledge and expertise, and encouraging knowledge sharing.

SNS can support knowledge processes by creating the paths through which they operate. For example, the groups that organizations use to create knowledge and the external contacts from which knowledge is acquired are both enabled by SNS. An example of retrieval of internal organizational knowledge in Military Bank was when a member was faced with a technical difficulty and was able to use Nexus to connect with a distant contact to provide direct assistance in resolving the issue outside of the normal bureaucratic request channels (Leidner et al., 2010). Similarly, the social capital generated by SNS set the conditions for knowledge sharing within organizations, where mutual friendship can create the required trust and motivation to affect the knowledge transfer (Huysman and Wulf, 2006). Finally, decision making in organizations is a complex process characterized both by information scarcity and overload. SNS can provide linkages to find the individuals in an organization with the scarce relevant information amongst the over-abundant irrelevant.

As SNS are focused on networks, their primary benefit is in the creation and maintenance of communities and networks of practice. Social networking software centers on the missing context in knowledge management through the navigation of social networks to find relevant content and sources of expertise (Parise, 2009). In addition to navigation of existing networks, Spertus, Sahami, and Buyukkokten (2005) suggested that SNS can use topographies of networks to recommend new communities to users based on membership characteristics. SNS have been demonstrated to support pre-existing social relationships more than the establishment of new ones, efficiently reinforcing weak ties (Ellison, Steinfield, and Lampe, 2007). This supports our view of networks of practice being primarily, but not exclusively, based on online activity.