Mapping the field

From our prior discussion, it is evident that a great deal of interesting research is taking place. However, it is also clear that most empirical studies in this area focus on a few specific explanatory variables, sometimes on an ad hoc basis, providing only a partial explanation to the overall phenomenon. Moreover, different streams of research have their own norms about levels of analysis data and variables. While each study has the potential to add to our comprehension of a given facet of alliance learning, it also contributes to the fragmentation of our understanding. The big picture is lost.

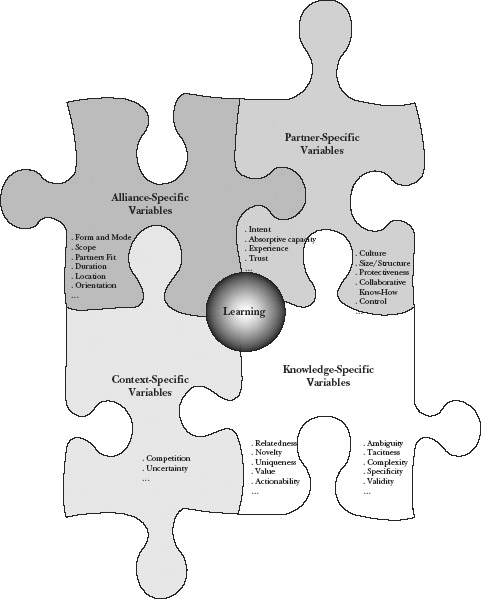

To address this problem, we propose a generic taxonomy of variables related to the ‘how?’ question in Figure 27.1. Four distinct blocks of explanatory variables compose this conceptual framework and help organize logically variables of interest: (1) alliance-specific variables, (2) partner-specific variables, (3) knowledge-specific variables, and (4) context-specific variables.

Figure 27.1 Learning and Alliances: Theoretical Building Blocks

For each block, we provide a list of pertinent variables. Lists are illustrative rather than exhaustive. The first block, alliance-specific variables, refers to many of the variables we have already introduced and discussed that may facilitate or impede the learning process. For instance, the importance of the form of the alliance (e.g. equity versus non-equity based) on learning constitutes a significant research question for many researchers.

Partner-specific variables, the model’s second block, subsume many critical research variables such as absorptive capacity, prior experience, strategic intent, trust, protectiveness, and collaborative know-how. Much attention has been paid to issues surrounding trust and protectiveness, a major concern being proprietary know-how bleeding to partners (Hamel, Doz, and Prahalad 1989; Hamel, 1991; Khanna, Gulati, and Nohria 1998; Kale, Singh and Perlmutter, 2000; Kale and Singh, 2009).

Effective management of networks at the inter-organizational level also serves as a vital mechanism for knowledge acquisition. There are different kinds of networks and different schools of thought about the types of networks most conducive to learning. Some theorists emphasize exploiting structural holes in inter-firm networks to limit redundancy and to have a unique combination of access to information and knowledge by virtue of a distinctive position. Social network theory stressing cohesion and strength of ties suggests that the trust and social capital built up through dense repeated relations increases knowledge flows within these networks. These approaches have divergent views concerning the mechanisms and operationalizations of their transmission. Both are promising avenues, though we believe they probably will prove to explain effectiveness of different types of learning and knowledge exploration.

A key concept underpinning both approaches so far and the concept underlying the ‘how’ in organizational learning more generally is that of absorptive capacity: the ability to identify, assimilate, and exploit knowledge (Cohen and Levinthal, 1989). To study knowledge transfers, it is helpful to distinguish between knowledge-seekers and knowledge-providers (Simonin, 1999a; 2004) or learning versus teaching partners (Inkpen, 2001). In the IJV literature, Lyles and Salk (1996) identified structures and processes contributing to an IJV’s capacity to absorb knowledge from the foreign parent. These included a flexible organization, written business plans and goals, a clear division of labor, and training by the foreign parent. These variables suggest (albeit indirectly) a mode of HRM and organizing that shapes cognitive orientations and informational networks within the alliance organization itself. Since then, Lane and Lubatkin (1998) have introduced the notion of relative absorptive capacity: the relatedness of the partnering firms’ knowledge bases, organizational structure and compensation as proxies for similarity in the norms and learning processes in the organizations, and dominant logics as a proxy for the motivation and ability to use the knowledge acquired. Lane, Salk, and Lyles (2001) found support for the relative absorptive capacity construct in their study of IJVs. In their study, the relatedness of knowledge and organizational characteristics of flexibility and training by the foreign parent predicted knowledge acquisition by the foreign parent, while the dominant logic (differentiation) and training in the IJV (a diffusion mechanism) predicted performance.

Both experiential (through training, learning-by-doing) and non-experiential learning (via proximity, observation) are implied by these studies. In other research that looks at learning by firms in geographic clusters, flows of personnel are viewed as mechanisms for the grafting of new knowledge and skills from one firm to another (Almeida and Kogut, 1999). Moreover, proximity provides opportunities for mimetic learning. As such, expatriates are viewed as key agents and facilitators of knowledge transfer in MNCs (Minbaeva, 2005; Simonin and Ozsomer, 2009).

The third block, knowledge-specific variables, was discussed earlier under the ‘What?’ section. The central point here is the determination of knowledge characteristics that create ambiguity and value. Ambiguity affects comprehension and transferability. Value stimulates learning intent for the knowledge seeker and encourages protective behaviors by the knowledge holder. Finally, context-specific variables, the fourth building block of our model, subsume non-controllable variables that may be sources of noise, but also motivation enactment of strategic intent to become an active, focused, or better learner or teacher.