A Comprehensive Model of Learning and Forgetting

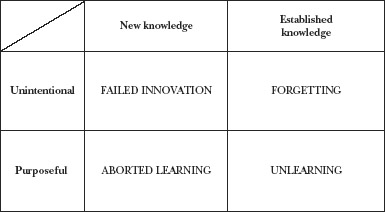

The apparent contradiction of these two streams of work—knowledge loss as simultaneously necessary and competence enhancing and also unwelcome and competence destroying—requires some sort of theoretical explanation. It also raises the question of whether there are other types of knowledge loss. Beginning with these observations, we have developed a framework useful in understanding the types of knowledge loss that occur in organizations (see Figure 20.1). First, we begin by differentiating types of knowledge loss based on the intentionality associated with it. Focusing on the intention behind knowledge loss allows us to change the onus from the outcomes of the process of forgetting (e.g. whether it was good or bad for the organization) to the organizational activity that preceded it. At its most basic, all forms of knowledge loss are the same; it is the relationship between the knowledge loss and the intention behind it that makes it positive or negative. In refocusing on intentionality, we can capture the role of managers in the process and provide a more useful set of categories of knowledge loss: in the first case, the intention is that forgetting shouldn’t occur; in the second, it is that unlearning should.

Figure 20.1 Modes of Organizational Forgetting

In addition to intentionality, the degree of embeddedness of the knowledge that is lost needs to be taken into account. From our empirical work on knowledge loss, we believe it is important to differentiate between recent learning that has not yet been deeply incorporated into the routines of the organization, and pieces of knowledge that have been part of the organization’s stock of knowledge for a long time and are therefore deeply embedded. We also found that the degree of embeddedness made a significant difference to how and why knowledge was lost, and we therefore argue for its use as a second dimension in our typology.

From these two dimensions, four types of organizational forgetting emerge: forgetting, unlearning, failed innovation, and aborted learning. These four types are presented and discussed below. We also provide a few illustrative vignettes for each of the categories drawn from a research project that we conducted and that served as the basis for a series of papers on the dynamics of forgetting (Martin de Holan and Phillips, 2004b), the management of organizational forgetting (Martin de Holan, Phillips, and Lawrence, 2004) and forgetting as a strategic activity for the organization (Martin de Holan and Phillips, 2004a).

Forgetting: the involuntary deterioration of embedded knowledge

We focus in this section on the degradation of knowledge after it has become embedded in the organizational memory system. As discussed above, we refer to this form of knowledge loss as forgetting. In our research, we observed several instances of forgetting where performance unexpectedly fell after having reached a level that was deemed satisfactory for some time. In these situations, instead of observing continued increasing gains in productivity and/or quality as cumulative output increased, we observed either higher costs or lower quality, or sometimes both. In these cases the learning curve predictions held, but only for a period: after reaching a plateau, the output then decreased. Furthermore, in some cases it was not just a matter of quality; the organization was, after a time, completely unable to invoke the routines that led to the satisfactory performance, regardless of the quality of the performance it had attained in the past.

We attributed that change in performance to an involuntary loss of established knowledge. A hotel manager in our study described the process as follows:

We calculate the daily cost of food and beverages. As soon as a new manager (of Food and Beverages) starts, he starts well, and then there is a phase where you have to watch closely (or the cost of food will increase again). In a kitchen, the cost depends on how closely you watch everything. That is fundamental. You have to see what goes out, what comes in, and you have to monitor that very closely. As soon as (the manager) stops checking that, his performance (cost of food in relation to quality) goes down. We have seen that with our Cuban chefs. We hire one of them and in two weeks the cost of food is sky-high, and only then it stabilizes. We haven’t been lucky with them.

(Resident Manager, Key Hotel)

Based on our evidence, we can suggest that for traditional learning effects to occur, organizations need to initiate activities that ensure the learning is incorporated into the stock of knowledge, and then that it is maintained over time. Our findings give support to the view that learning and maintaining the acquired knowledge are two distinct activities that require significant managerial attention but are intrinsically different in nature. Furthermore, more and better maintenance activities will be needed to ensure lower rates of forgetting. It is not simply the level of attention given to the maintenance of the stock of knowledge, but also the quality of that attention that influences the levels of retention (or, as mentioned by Argote, 1999, the dissipation rates).

Unlearning: The purposeful destruction of established knowledge

The second dimension of knowledge loss identified is unlearning; that is, knowledge loss that is actively desired by the organization. As one of the hotel managers in our study observed:

The Canadian (managers of the hotel) act as if this were some suburb of Montreal. They still have to understand that we are in Cuba and that certain things cannot be done their way. They want us to use their system (developed and tested in Canada), and that system does not work here, we need new ways of doing things that take into account the specificities of the country.

(Resident Manager, Montelimar Hotel)

In these situations, unlearning was needed primarily as a way to make room for new knowledge; discarding knowledge that had once been functional for the organization but was now acting as a hindrance to required learning. Another insight we can draw from this statement is that unlearning is a separate process from the process of learning. It is distinct from it, but in at least some cases has an important influence on the outcome of the learning process.

From our findings, we argue that the rate of learning that an organization can exhibit is influenced by the rate of unlearning that the organization can deploy at a certain moment. Since unlearning involves the elimination of knowledge that is no longer needed, its existence influences the rate at which knowledge can be absorbed and, in extreme cases, whether future learning can happen at all.

The overall effectiveness of knowledge mobilization (including organizational learning, but also knowledge transfer from within the organization and vicarious learning) is likely to be influenced by the presence or absence of unlearning. When organizational learning requires that new routines and new standard operating procedures replace old ones, processes of forgetting can influence the success of these learning processes by facilitating or making more difficult the assimilation of what has been learned. These observations can be applied in parallel to the ones mentioned by Newstrom (1983): with the exception of the situation in which the objective of learning is simply to create a behavior that did not exist previously, all the other categories (sustaining previous behavior, increase or decrease behavior or skill level, add new behavior to repertoire and replace behavior with another one) will require less effort in the presence of unlearning and, conversely, will be more effortful when unlearning is not present or is poorly managed.

Also, the need for unlearning can be related to the quality of the memory systems of the organization. As Devadas Rao and Argote (2006) argue, ‘[u]nderstanding why organizational knowledge depreciates involves understanding where organizational knowledge is stored or retained in the organization’s memory.’ Building on these ideas, it is clear that the quality of the organizational memory system will have a strong influence on the rates of learning and forgetting: better, more developed memory systems will tend to retain knowledge longer, as the behaviors and the cognition will be deployed in a more comprehensive way in the organization, and will have more material supports than otherwise. In situations where memory systems are more developed, unlearning will be more important.

Failed innovation: the inability to integrate new knowledge

This sort of knowledge loss is related to the inability to integrate new knowledge into the organization once the original problem is solved. That is, a failed innovation occurs when knowledge is transferred from another organization, or created by the organization itself, but is not retained: the solution does not ‘stick.’ When this happened in our study, we observed that an organization was able to perform a task for the first time, but was unable to achieve the same level of performance the second time around, or in some cases even unable to perform it again at all.

In this case, what had been learned had dissipated rapidly; it involuntarily disappeared from the organization almost immediately after it was created. We found several instances of failed innovation in our research, and there was a clear common theme among the managers we interviewed. For example, ‘if you do not follow-up, it is back to step 1’ or ‘you go on vacation, and when you are back, the standards are gone.’ Although initially we hypothesized that these were examples of failure to transfer or to create knowledge, we later realized that the organization had been able to use that knowledge, but only for short periods of time.

For example, a gala dinner for the elite of the country and diplomatic representatives from abroad was organized at one hotel with great success: the general impression was that the quality of the premises, the food, and the service were impeccable. Yet, a few weeks later, a much more modest gathering failed, as the quality of the food and service was mediocre. Subsequent failures moved the organization to cancel its plans to add receptions to its service offering, depriving it of a profitable source of income. As one manager explained:

I think it’s easy to get to a high standard; it’s not difficult. I can go to another hotel and we can have the best meal (banquet) tomorrow there, without a problem, the best service for one day. But to keep it, to keep the standard is very difficult.

(Food and Beverage Manager, Withwind Hotel.

This quote suggests that the integration of knowledge into an organization’s memory system is a difficult task with often imperfect results. We can hypothesize that the rates of knowledge dissipation are closely related to the quantity and quality of the efforts put in by the organization to store that knowledge, and to the quality of the memory system itself. More intense management effort and attention may lead to lower rates of dissipation, while less effort (or no effort at all) will likely produce a very high dissipation rate.

Our findings and the hypothesized relationships formalize Day’s idea:

[O]nce knowledge has been captured . . . it won’t necessarily be retained or accessible. Retention requires that the insights, policies, procedures and on-going routines that demonstrate the lessons are regularly used and refreshed to keep up-to-date.

(Day, 1994b: 23)

Without organizational members’ effort to retain knowledge, forgetting is inevitable. Simple innovation or transfer is not enough. Rather, management attention must be spent as much on ensuring the new knowledge is embedded in the organization’s memory as it is on its innovation in the first place.

Aborted learning: avoiding the integration of new knowledge

Innovation is often a central concern of organizations, but not everything that is new is useful or desirable. As one hotel manager pointed out:

[At first] we imported the structure [sets of rules and procedures and formal descriptions of jobs] of Superb Hotel, and very quickly we realized that it did not work well here, perhaps it was because there were no foreigners among us, or maybe because our managers were not prepared for it. And we saw contradictions appearing at all levels, and our operating procedures were not implemented, and the same hierarchical level that decided on their implementation had to check to make sure they were actually applied. Then we decided to change the structure, to work differently so we would not drown in meetings that did not get the problems solved.

(General Manager, Caribbean Hotel)

In this case, the organization developed new knowledge (a new structure was adopted, new operating procedures were introduced, and new patterns of communication established), but it became apparent that what the organization had learned was not appropriate, and the managers had to move quickly to break the new routines, change the new structure, and re-establish more workable routines and structures.

Although in the case cited above the knowledge had been transferred from another organization in the form of a structure, similar phenomena were observed in organizations that had developed their own knowledge in the form of successful innovations. We observed that organizations that were good at innovating also had to be good at forgetting, because they had no a priori guarantee that their innovation would be adequate for their organization in the particular context they found themselves. Organizations that created solutions for problems had to be prepared to acknowledge that the solution they had found may not be adequate for the overall organization and had to be dropped before it became embedded in the memory system.

In more general terms, organizations skilled at knowledge creation and learning in general often seemed to be in the situation where they needed to discard what they had developed. Many experiments meant a lot of forgetting, and inadequately managing this process led to a decrease in performance as organizations picked up undesirable innovations. Successful innovative organizations probably possess more and better mechanisms to prevent new knowledge from entering their memory systems.